1. Be Curious, Be Critical!

most people are fools, most authority is malignant, God does not exist, and everything is wrong.

‘The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information’ [Miller, 1956] is a very famous human factors research paper, written in the mid—Fifties and concerning Psychoacoustics. The paper is interesting because it has spawned an often incorrectly understood, usability principle. That our working memory can only handle seven (± 2) items at any one time and therefore we should only make menus or lists a maximum of seven items long.

However, “Miller’s paper is a summary/analysis of research findings couched in the form of bits per channel. He amusingly relates the fact that the number seven seems to be plaguing his every move because seven seems to appear repeatedly regarding the amount of information that can be remembered or differentiated by humans. However, there are two caveats to this assertion: firstly, that the user is required to make absolute judgements of unidimensional stimuli and secondly that that stimulus is not clustered. This last point is quite important because using clustering means that we can remember or distinguish more than the unitary seven. For instance, we can remember seven characters in sequence, seven words in order, or seven phrases. In reality then, we have trouble differentiating uni-dimensional stimuli such as audible tones played without reference to each other, but we can differentiate more than seven tones when played in a sequence, or separately when multiple dimensions such as loudness and pitch are varied. Further, we can remember more than seven things within a list especially if those things are related or can be judged relatively, or occur as part of a sequence.

1.1 Being Critical

So this is a well found psychological finding (and very well written paper) that working memory can handle seven (±2) arbitrarily sized chunks of absolute uni-dimensional stimuli. And becomes the often quoted but mostly incorrect usability/HCI principle that you should only include seven items in a menu, or seven items in a list… and on and on.”

Indeed, this often incorrectly understood usability principle is a misconception that has become a firmly held belief; this is the ‘wrongness’ that Ted alludes to, and there are plenty of others. Let’s look at a few.

1.1.1 Buzz and Hype

Jacob Nielsen famously suggests that usability evaluations can be conducted with only five people, and this will catch over 80% of the usability errors present [Nielsen, 2000]. In reality, Nielsen added a lot of caveats and additional conditions to be met, which have been lost from the ‘buzz’ surrounding the ‘five users’ evaluation work. Eager usability practitioners hooked upon this five user message as a way of justifying small studies, even when those small studies tested multiple and disjoint usability tasks. Even user studies that do not try to generalise their results need to make sure that the kinds of tasks performed are both limited and holistic. With these kinds of usability tests, Faulkner [Faulkner, 2003], demonstrates that the amount of usability errors uncovered could be as little as 55%. Further, Schmettow [Schmettow, 2012] tells us that user numbers cannot be prescribed before knowing just what the study is to accomplish. And Robertson [Robertson, 2012] tells us that the interplay between Likert-Type Scales, Statistical Methods, and Effect Sizes are more complicated than we imagine when performing usability evaluations.

1.1.2 Shorthand

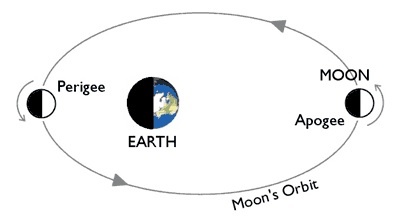

The Moon Orbits the Earth. More common misconceptions work their way into our understanding, usually because of a certain shorthand that makes the concepts more easily expressed, at the expense of introducing some minor errors. For instance, the Moon does not orbit the Earth (see figure Moon’s Orbit). Well, it kind of does, but in actuality the Moon orbits the combined centres of gravity of both the Moon and the Earth. This just so happens to be very near the centre of gravity exerted by the Earth because the Moon’s centre of gravity is so small.

In general, this misconception does not affect most people’s everyday life. However, it is technically important — how celestial bodies interact with each other is a major area within the study of Astronomy.

1.1.3 Sounds Right

The Earth is Closer to the Sun in the Summer than in the Winter. Let’s look at another misconception, the Earth is closer to the Sun in the summer than in the winter, and it is this closeness which accounts for the seasons. Again, this is kind-of right, part of the Earth is nearer to the Sun in the summer than in the winter, however, the Earth as a whole is not. The seasons are accounted for by the Earth being tilted on its axis by 23.4°. As the Earth orbits the Sun, different parts of the world receive different amounts of direct Sunlight and this accounts for the warming or cooling. But this warming or cooling is based on the angle of the Earth’s axis in relation to the Sun. And, therefore, the nearness of either the southern or the northern hemisphere to the Sun, not the Earth as a whole.

In your work as a user experience specialist, you often find there are many, unsaid, or shorthand’s expressed by users. These are technically incorrect but are satisfactory for their everyday work, but may introduce large problems with your technical solutions.

1.1.4 Common Sense

Blind People Can’t See. Certain facts seem to be ‘common sense’, you should always question common sense pronouncements. For instance blind people cannot see, this seems obvious, this seems like common sense, and in actuality it is incorrect. The reality of the situation is that some blind people, a very small percentage of blind people (termed profoundly blind) cannot see. In reality, the vast majority of blind people can see colours, shapes, blurred objects, and movement. In short most blind people can see something; only 4% can see nothing at all and are ‘profoundly’ blind.

1.1.5 Obviously!

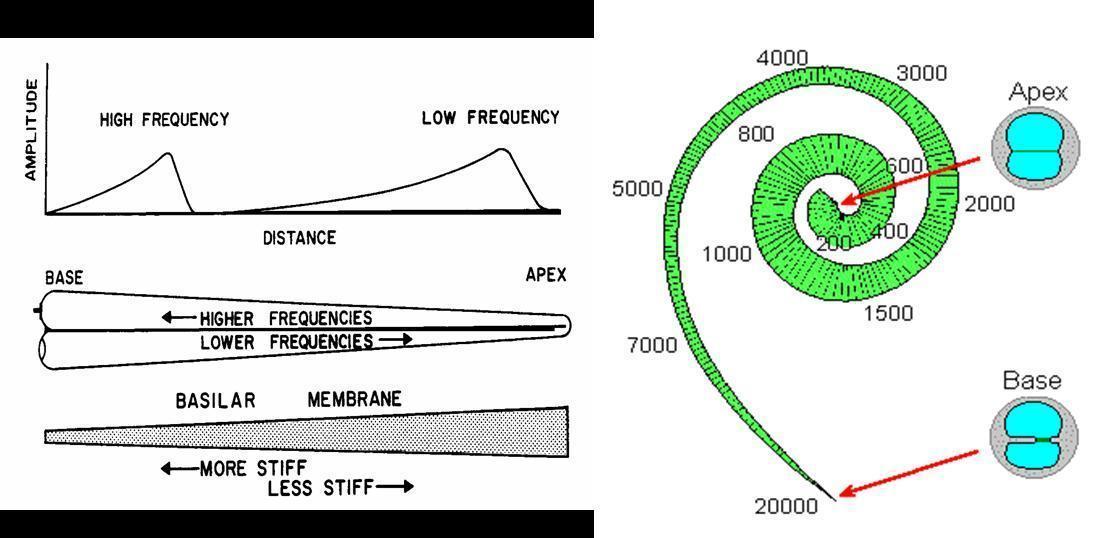

Vision is Parallel, Hearing is Serial. It is often thought that vision is parallel, in that we can see multiple objects all at the same time whereas hearing is serial because we can only hear one sound. This is incorrect, in reality the basilar membrane of the cochlear experiences different frequencies from its base to apex (see Figure: Basilar Membrane). These nerve cells are connected to different areas within the brain that are responsive to different frequencies and those frequencies are also processed in parallel.

1.1.6 A Little Knowledge is a Dangerous Thing

All Brains Have the Same Organisation. We all know that the brain has the same organisation. Indeed, we can see this in many diagrams of the brain in which there are specific areas devoted to specific jobs, such as vision, language, hearing and the like. But just how true is this? In reality, this is not as true as you may imagine. The brain mostly develops up to the age of twenty-one and within that time a concept called neuroplasticity is in effect. And states that the brain can change structurally and functionally as a result of input (or not) from the environment. This means that the brain can change and re-purpose unused areas [Burton, 2003]. For instance, the visual cortex of a child who has become profoundly blind at, say, ten is overtime repurposed to process hearing, and possibly memory and touch. The brain develops in this way repurposing unused areas and adapting to its environment until development slows down at the age of twenty-one.

1.1.7 One Final Thought…

Look at this famous video from Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris1. It requires you to count passes of a Basketball. Try to count them now, and then skip ahead for the result.

1.2 Being Curious

The story of UX and, more widely, HCI is not one you’d expect and you should always maintain a healthy curiosity when discussing it; it certainly isn’t as two–dimensional as just front end coding.

1.2.1 The Collision of Two Opposing Ideologies

In the past we characterised practical human computer interaction in terms of usability and interaction engineering (in some cases accessibility was included but mainly as an afterthought). In this case, we decided if an interface was usable and the interaction design was good, based on tangible, measurable metrics such as task completion time. These kinds of metrics enabled us to understand the interactive experience in terms of time, theorising that the least time spent using the interface, the better; and this may have been, in some ways correct, as most computers were used in work situations.

As time has passed our concept of the computer and the interface evolved such that computers were no more tied down to the desk but could be mobile or ubiquitous, and the interface was not solely confined to software but may also include aspects of hardware, moving computers from the workplace and into the consumer product domain. Our ways of measuring and valuing the goodness of these interfaces however remained the same, task completion time, errors and error rates, correction times, Fitts Law pointing predictions, etc. Indeed this was the scientific or classic view of technology. At this point intangibles were seen as being soft science, unmeasurable and too open to incorrect interpretation. Other aspects, which might also affect how interfaces were experienced, but which could not be directly measured, and which relied more on subjective views of the user was seen as being, at best inconsequential, and at worst just plain old bad-science.

This clash of ideologies runs large through the whole of UX, its main theme being how to unify both the scientific and the romantic; the classic and the aesthetic; the tangible and the intangible; the measurable and the experiential. Indeed, UX is our attempt to unite classic HCI with modern ideas of experience and perception in which accessibility, usability, and interaction engineering (tangible, scientific, measurable) are combined with aesthetic, emotional, fun, affective, collaborative, and gameplay (intangible, humane, difficult to measure).

By understanding the clash of world we can also understand the more successful combination of these two – seemingly opposing – ideologies into a unified and cohesive whole as practically applied in UX. By understanding these nuances we can better understand what issue we will need to overcome in future UX design, build, and evaluation and also begin to value – and better understand – the subjective qualitative views of the interactive experiences of our users.

1.2.2 Perception of the User Experience

One of the other major themes of UX is that of perception, and the differences which lie between people and their experience of the world. The complicated experiences and perceptions of experience should be taken as warnings to anyone working in user experience. Our perceptions are complicated and incredibly difficult to categorise; what may seem to be obvious to one person, maybe obscure to another. User experience, as opposed to classical HCI, takes these different subjective perceptions into account in its desire to create practical pleasing experiences for each user.

Perception is something not normally measured or quantified in classic HCI and so only in the modern additions of emotion, fun and dynamic interaction can these intangibles be acknowledged. UX shows us that experience can be massively divergent, and that outliers are as important as the general cases (if not more so).

1.2.3 Framing of Science in the User Experience

In our comparison of subjective and objective paradigms – the classical and the romantic – we must also take into account science and the scientific method especially in terms of empiricism, objectivity and the belief systems that arise around both objectivity and subjectivity.

Science has its limitations. For instance, many people have a common understanding of quality, in that they can tell quality when they see it, but quality is difficult to measure in any empirical or objective way; or describe with any degree of clarity. It seems in some ways an emergent property, or an umbrella term under which other more easily measured objective indicators can play a part. However, the richness of the description of quality is difficult to place only in such objective terms. So we can see that science cannot be the only measure of user experience, because science is mostly about generalisation, and because we do not have a full model of the universe; we therefore do not know all the variables which may arises to influence the user experience of a single individual. By nature we must conclude, in some regard, that objective, empirical science cannot give us all the answers at this time (until our model is complete), only the answer to testable questions.

This discussion of science is directly related to our discussions of the application of user experience, how we understand modern user experience, and how older styles of human computer interaction serve as an excellent base, but cannot provide the richness which is associated with the intangible, and often unquantifiable subjective, and emotional aspects which we would expect any user experience to comprise of.

We must, however, be cautious. By suggesting that subjective measures may not be testable means that we may be able to convince ourselves and others that a system is acceptable, and even assists or aids the user experience; while in reality there is no evidence, be it theoretical or experimental, which supports this argument. It may be that we are using rhetoric and argumentation to support subjective measures as a way of sidestepping the scientific process which may very well disprove our hypotheses as opposed to support it.

1.2.4 Theoretical and Empirical User Experience

Notice, in the last section we discussed one fundamental of science, the fact that we can disprove or support a hypothesis, in empirical work we cannot prove one. We cannot prove a hypothesis because in the real world we are not able to test every single condition that may be applied to the hypothesis. In this case we can only say that our hypothesis is strong because we have tried to destroy it and have failed.

However, those trained in rhetoric, in theoretical not empirical work, has a conception of science which is different to ours. In theoretical science it is quite possible to prove or disprove a hypothesis. This is because the model of the world is known in full (‘closed world’), all tests can be applied, all answers can be evaluated. This is especially the case with regard to mathematics or theoretical physics whereby the mathematical principles are the way the world is modelled, and this theoretical world works on known principles. However this is not the case in user experience, and it is not the case in empirical science whereby we are observing phenomena in the real world (‘open world’) and testing our theories using experiments, which may be tightly controlled, but are often as naturalistic as possible. In this case, it is not possible to prove a hypothesis, because our model of the world is not complete, because we do not know the extent of the world, or all possible variables, in complex combination, which are able to affect the outcome.

In real-world empirical work we only need one negative result to disprove our hypothesis, but we need to have tested all possibilities to prove our hypothesis correct; we just don’t know when everything has been tested.

1.2.5 Rhetoric, Argumentation, and the User Experience

So, how can we satisfy ourselves that subjective, or intangible factors are taken into account in the design process and afterwards. While we may not be able to measure the subjective outcomes or directly generalise them we are able to rationalise these aspects with logical argumentation; and rhetoric – the art of using language effectively so as to persuade or influence others – can obviously play a key role in this. However, you will notice that the problem with rhetoric is that while you may be able to persuade or influence others, especially with the aid of logical argumentation, your results and premise may still be incorrect If you haven’t thought of, or don’t predict, the [counter]arguments that will be made, and have your own convincing counter arguments you’ll loose - you may be right, but if you are, your arguments and counter arguments should be complete; that’s the point of rhetoric and rhetorical debate.

Remember though, that with the user experience it is not our job to win an argument just for the sake of argumentation or rhetoric itself. We are not there to prove our eloquence, but we are there to support our inductive and deductive reasoning, and our own expertise when it comes to understanding the user experience within the subjective or intangible.

Further, the difference between a good UX’er and a bad one, like the difference between a good mathematician and a bad one, is precisely the ability to select the good facts from the bad ones on the basis of quality. You have to care! This is an ability about which formal traditional scientific method has nothing to say.

1.2.6 Values, and the Intangible Nature of the User Experience

‘Values’ are more important that you might imagine when working with humans, and it is useful to remember this in the context of understanding the user experience. In reality, many of the intangibilities which arise in UX work stem from these often hidden values.

More interestingly however, values which are often related to the world-views of individuals and more importantly their perception of these values, influences what they consider to be important.

We see the world not as it is, but as we are — or, as we are conditioned to see it.

– Anaïs Nin … or Stephen R. Covey

Indeed, point here is that people bring their own values based on previous experience and their emotional state of equilibrium to any experience. These aspects are intangible and can be difficult to spot especially with regard to understanding the user experience. However, we can also use these values and world-views (if we have some idea of them) to positively influence users emotional response to an interface or interaction. Remember, we have already discussed that the expectation or perception of an experience, be it good or bad, will influence to a large degree the perception of that actual experience once enacted.

1.3 Summary

If there are two traits you should possess as a UX specialist, they are curiosity and the ability to be constructively critical. As we have seen, there are many reasons why errors and misconceptions can be embedded within both an organisation and the systems by which it runs. We can also see that if people want to believe their software has a good user experience they often will do. They are often blind to the real nature of the interface software, or systems, which they have built.

In UX, there is often no 100% correct answer (that we as UX specialists can derive) when it comes to creating, building, and then testing a system. The unique nature of the human individual means that there are many subjective aspects to an evaluation. Understanding whether the interface is correct is often based on anecdotal evidence and general agreement from users, but is also based on a statistical analysis of quantitative measures. This area of uncertainty can allow rhetoric to be applied, whereby an argument may be proposed which seems stronger than your empirical evidence, but which is not empirically supportable. Also, there is also the danger that a sloppy or incorrect methodology will taint the empirical work such that the answers derived from a scientific method are incorrect. There are many cases of bad science2, and incorrect outcomes from supposedly well-conducted surveys. For instance, evidence suggests that 95 percent of our decisions are made without rational thought. So consciously asking people how they will behave unconsciously is at best simplistic and at worst, can really mess up your study.

One of the most well-known examples is the launch of New Coke. “Coca-Cola invested in ‘cutting-edge customer research’ to ensure that New Coke would be a big success. Taste tests with thousands of consumers clearly showed that people preferred it. The reality was somewhat different, however. Hardly anyone bought it.”3

In another set of studies4, people were asked what messages would be most successful at persuading homeowners to make certain changes, such as turning down the heating, recycling more, and being more environmentally friendly.

Most said that “receiving information about their impact on the environment would make them change. However, this made very little difference at all. In another study, people who said that providing them with information about how much money they could save if they reduced consumption led to them to use even more! Interestingly, the message that most successfully changed their behaviour (information about how neighbours were making changes) was pretty much dismissed as unlikely to have any effect on them at all.”

Remember, quantitative instruments such as controlled field studies, or field observations, will often be cheaper in the long run than questionnaire-based approaches. In all cases, if you are not curious and you are not critical you will not produce accurate results.

1.3.1 Optional Further Reading

- [J. L. Adams]. Conceptual blockbusting: A guide to better ideas. Basic Books, 2019.

- [Joseph CR. Licklider]. “Man-computer symbiosis.” IRE transactions on human factors in electronics 1 (1960): 4-11.

- [R. M. Pirsig]. Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance: an inquiry into values. Morrow, New York, 1974.

- [Suzanne Vega]. Tom’s Diner, A&M PolyGram, 1987.

- [Suzanne Vega] Vega, S. (2008, September 23). Tom’s essay. The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2022.