13. Principles of Engagement (Digital Umami)

Play has been seen as one of the most important and fundamentally human of activities.

– Johan Huizinga

I intended to call this chapter ‘Digital Umami’47 to convey the concept of something that is imperceptibly delicious. However, after much more reading over the years I decided on ‘Dynamics’ in part from Fogg’s [Fogg, 2003] – elaboration on Reeves and Nass [Reeves and Nass, 1996] – Social Dynamics. But then just last year I realised it should be called ‘Engagement’ and so here we are. The topics we will be looking at here focus on fun, enjoyment, cooperation, collaborative activities, and what has come to be known as ‘gamification’.

Gamification is causing a degree of controversy at the moment, but what is it? Well, Wikipedia tells us that: “The use of game play mechanics for non-game applications… particularly consumer-oriented web and mobile sites, to encourage people to adopt the applications. It also strives to encourage users to engage in desired behaviours in connection with the applications. Gamification works by making technology more engaging, and by encouraging desired behaviours, taking advantage of humans’ psychological predisposition to engage in gaming.

The UX camp, though, is split on its value. Pro-Gamification proponents argue “As the critics point out, some gamified products are just poorly executed. Just because you saw something in a game once doesn’t mean it’ll be fun in your product. But I think that most of the critics of gamification fail to take into account the wide range of execution that’s possible. Gamification can be applied as a superficial afterthought, or as a useful or even fundamental integration.” 48

While critics say: “More specifically, gamification is… invented by consultants as a means to capture the wild, coveted beast that is videogames and to domesticate it for use in the grey, hopeless wasteland of big business… The rhetorical power of the word ‘gamification’ is enormous, and it does precisely what the ‘they’ want: it takes games – a mysterious, magical, powerful medium that has captured the attention of millions of people – and it makes them accessible in the context of contemporary business… Gamification is reassuring. It gives Vice Presidents and Brand Managers comfort: they’re doing everything right, and they can do even better by adding ‘a games strategy’ to their existing products, slathering on ‘gaminess’ like aioli on ciabatta at the consultant’s indulgent sales lunch.” 49.

For a moment, however, let’s just forget all the buzzwords and concentrate on the real concepts that underpin the ideas of ‘gamification’, ‘funology’, and ‘social dynamics’. The key concepts [Anderson, 2011], as I see them, relate to a level of interaction beyond that which would normally be expected from standard interfaces and applications. This additional level may involve collaborations and partnerships with others, competitions, or the pursuit of a tangible prize or reward. But in all cases, a premium this placed upon the enjoyment, fun, and enhanced interactivity; in short ‘engagement’50. What’s more, I would also refer to my original thoughts on the subject – there is a certain added ‘deliciousness’, which seems to be imperceptible; as with Affective,’You’ll know it when you see it’.

13.1 Group Dynamics

Dynamics are discussed variously as ‘Social Dynamics’ [Fogg, 2003], ‘Social Roles’ [Reeves and Nass, 1996], ‘Socio-Pleasure’ [Jordan, 2003], ‘Social Animals’ [Weinschenk, 2011], and ‘Playful Seduction’ [Anderson, 2011]; I’m sure you’ll be able to find plenty more. However you conceive it, group dynamics is trying to ‘firm up’ quite a tricky and ill-defined concept – that of social interaction with other users, or via a more humanistic, naturalistic, or conversational interface. The idea is that adding the energy that is often found in human interactions, to our interactions with the application, will propel us into having better user experiences because they are closer to our expectations of person-to-person interactions.

These more naturalistic interactions are based on our knowledge of human psyche and the human condition (one nice example is the Microsoft Courier Tablet – a prototype – see Figure: Microsoft Courier Imitating a Real World Notebook). We know that in most cases humans are socially motivated and live in groups with a strong tie to people in collaborative situations. Indeed, performing tasks in groups bonds humans to each other, as well as the group; in this case, there is an increased emotional benefit as people are comfortable feeling part of the whole. Further, we also know that people are likely to imitate and to empathise behaviour and body language; and our brains respond differently to people we know personally or don’t know, and situations we know and don’t know. It seems only appropriate then that we should work better in social situations where the interface can imitate some of these social niceties, or we can perform interactive tasks as part of the group, or interactions that make us feel like part of a group. Indeed, people expect online interactions to follow social rules, this is logical in some regard because the application software has been created by a human (who was also following a set of social rules).

Hierarchies often form as part of the social interactions for these groups, and so in the interactive environment, we need to decide whether we feel that the computer is a subservient to the user. Or whether the computer is a master and should be an autonomous guide with the user only consuming information with no regard as to how it was generated. However, from teammate research, the relationship seems to be one that should be a peer relationship. Certainly by creating a peer relationship we get the best of both worlds in that the computer can do much of the work we would not like to do ourselves while also dovetailing into the user’s feeling of enhanced self-image and group membership. The computer is neither subservient, nor master, and this partnership of equals often works better for a task to be accurately accomplished.

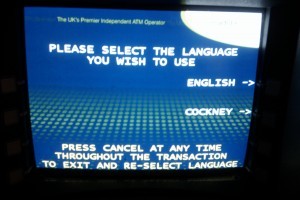

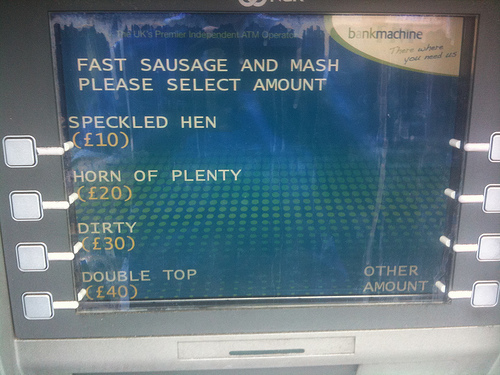

In these cases, how may we pursue the dynamics via our interactions with the interface? Without a doubt, this is a difficult one to answer, and there seems to be no definitive idea so far. Most experts discuss this kind of group dynamics in the context of a pre-existing example, but are often very wary of creating practical principles or giving practical advice to developers and UX specialists; again most refer to this using the ‘You’ll know it when you see it’ get-out-of-gaol-free card. However, it seems that you may wish to think about going beyond what you would normally see as being the functional requirements of your interface. By knowing that we are interested in groups, collaborations with peer groups, that we feel more secure and more likely to perform better within groups, you may wish to include functionality that may not seem directly relevant but may increase performance. Here I’m thinking about systems that may link up members of a particular team, allow the team to see the results or the working practices of other teams, or to bond by friendly competition. There may be a facility for online chat or transcripts such that users can be supported within their team by each other. Further, the interface may conform to the social norms expected within the society it is deployed. In this case you may wish to alter your language files, or which profiles, to use common local dialects, colloquialisms, or jargon; we’ll see this a little more detail in the cockney rhyming slang ATM examples next.

There are plenty of places where group dynamics already form an integral part of an application or interaction. These range from game based leaderboards found in an increasing number of online Web applications (such as backcountry.com) to the more subtle interactive group dynamics of the ill-fated Microsoft Courier Tablet (see Figure: Microsoft Courier Exhibits a High Level of Dynamics). From ThinkGeeks OMGWTFUN customer ‘Action Shots’ and ‘Techie Haiku’ to Amazon’s ‘Listmania!’ good group and social dynamics can be captured in most interactive software situations where there is a perceived positive outcome to the user. The main thing to remember, with most attempts at implementing group dynamics, is to be subtle and understated. If it is obvious that group dynamics is being applied with little gain for the user, their implementation is probably not going to be effective or produce the desired beneficial UX.

13.2 Funology

“Play has been seen as one of the most important and fundamentally human of activities. Perhaps the best-known study on the subject of play is Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga. In it, he argues that play is not only a defining characteristic of the human being but that it is also at the root of all human culture. He claimed that play (in both representation and contest) is the basis of all myth and ritual and therefore behind all the great ‘forces of civilised life’ law, commerce, art, literature, and science.” —Huizinga, 1950

Funology [Blythe, 2003] , is a difficult area to define because the majority of viewpoints are so very certain regarding the theories and frameworks they present, seemingly without any direct scientific support. Indeed, most of these seem to be derived from common sense, anecdotal evidence or, paradoxically, the view of a higher well-regarded source; with the results placed within a fun-o-logical framework. Indeed, even when user case studies are presented, most of the work points towards software and hardware development that does not have any summative user testing and relies solely on the views of a small set of individuals. In this way, it is very akin to the individualist experiences expressed as acceptable in Law 2009.

This may not be a problem for work coming from product design (the main proponents are from a product design background), and indeed, this fits in with the evolution of user experience and the parts of it which emanate from artefact design and marketing; there are very few hard tangible results here, however.

That said I still find the sentiment within this area to be important in that the experience of the user, their enjoyment, their delight, and the deliciousness of the software or application are often forgotten or ignored in a headlong rush to implement effective and efficient interfaces. Indeed, this enjoyment aspect goes into my current thinking on the practice of interface and interaction engineering within the software engineering domain.

But how do we synthesise the useful aspects of mostly anecdotal evidence presented within this area? In this case my method is simple, I have listed all of the pertinent frameworks and well-found theories from each different author, and have then looked for similarities or overlap within the sentiment of these concepts. At the end arriving at a list of principles of enjoyment and experience and are much like those in accessibility or usability, which may be easily remembered within the development process.

- Personalisation and Customisation: ‘relevance’; ‘surpass expectations’; ‘decision-making authority of the user’; ‘appropriateness’; ‘the users needs’; ‘don’t think labels, think expressiveness and identity’; and ‘users interests’.

- Intangible Enjoyment: ‘triviality’, ‘enjoyment of the experience’; ‘users desires’; ‘sensory richness’; ‘don’t think products, think experiences’; ‘don’t think ease of use, I think enjoyment of the experience’; ‘satisfaction’; ‘pleasure’; and ‘appealing-ness’; and ‘emotional thread’.

- Tangible Action: ‘goal and action mode’; ‘manipulation’; ‘don’t hide, don’t represent, show’; ‘hit me, touch me, and I know how you feel’; ‘don’t think of thinking, just do’; ‘don’t think of affordances, think irresistible’; ‘evocation’; ‘sensual thread’; and ‘spectacle and aesthetics’.

- Narrative Aids Interaction: ‘don’t think beauty in appearance, think beauty in interaction’; ‘possibilities to create one’s own story or ritual’; ‘don’t think buttons, think actions’; ‘connection’; ‘interpretation’; ‘reflection’; ‘recounting’; ‘repetition and progression’; ‘anticipation’; and ‘compositional thread’.

- Mimic Metaphor: ‘metaphor does not suck’; ‘instead of representing complexity, trigger it in the mind of the user’; ‘think of meaning, not information’; ‘simulation’; ‘identification’; and ‘evocation’; and ‘spatiotemporal thread’.

- Communal Activity: ‘social opportunities’ in terms of ‘connectivity’ and ‘social cohesion’; ‘variation’; ‘multiple opportunities’; and ‘co-activity’.

- Learning and Skills Acquisition support Memory: ‘repetition and progression’; ‘develop skills’; ‘user control on participation’, with ‘appropriate challenges’; ‘the users skill’; ‘transgression and commitment’; ‘goal and action mode’; and ‘instead of representing complexity, bootstrap off it’.

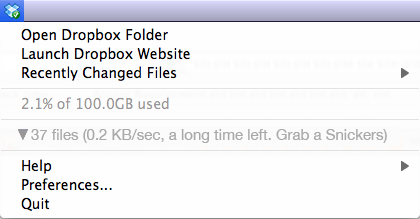

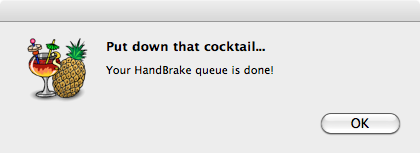

There are of course many different ways that fun like elements can be applied, and here there can be a blur between funology and gamification. Indeed, it is probably not particularly useful to draw a hard and fast distinction between what will be fun and will be a game, but one of the most common places for a fun component to be introduced into an interaction is by using amusing/unexpected language or concepts. This may be as simplistic as Dropbox’s ‘Grab a Snickers’ when file transfers have a long time left to run (see Figure: Dropbox Snickers), through to HandBrake’s notification to but down the cocktail you’ve been drinking while waiting for the HandBrake queue to complete (see Figure: HandBrake Cocktails).

Of course, how to apply these will be different based on the individual development underway. For instance, ‘Bank Machine’, a cash machine operator, has introduced Cockney rhyming slang to many of its Automated Teller Machines (ATM) in East London. Cockney rhyming slang is a form of phrase construction in the English language and originates in dialectal British English from the East End of London. Slang examples include: ‘dog-and-bone’ = telephone; ‘trouble-and-strife’ = wife; ‘mince pies’ = eyes; and ‘plates of meat’ = feet. In this case, people using the ATM’s can opt to have their prompts and options given to them in rhyming slang (see Figure: Cockney ATM Language Selection); as a result they will be asked to enter their Huckleberry Finn, rather than their Pin (see Figure: Cockney ATM PIN), and will have to select how much sausage and mash (cash) they want (see Figure: Cockney ATM Cash Withdrawal).

It is, however, difficult to understand if this level of ‘fun’ is popular with users. Indeed, in some cases, it may be seen as patronising, or an obvious ploy to curry favour with a section of the community, which may lead to resentment by those other sections of the community not catered for. I would also suggest that testing for the presence of ‘fun’ will be difficult because a fun experience is very individualistic and often intangible. However, it may be easier to look for its absence - or barriers to its realisation - as an appropriate proxy measure of its presence.

13.3 Gamification

“Gamification typically involves applying game design thinking to non-game applications to make them more fun and engaging. Gamification has been called one of the most important trends in technology by several industry experts. Gamification can potentially be applied to any industry and almost anything to create fun and engaging experiences, converting users into players.” —http://gamification.org

Gamification seems to include (I say seems as there are many different takes on this – as with much of this ‘Dynamics’ chapter): adding game-like visual elements or copy (usually visual design or copy driven); wedging in easy-to-add-on game elements, such as badges or adjacent products (usually marketing driven); including more subtle, deeply integrated elements like percentage-complete (usually, interaction design driven); and making the entire offering a game (usually product driven). I’d also suggest that gamification isn’t applicable all over.

It seems most gamification advocates suggest that game elements can be added in stages to a non-game interface. I think these can be separated into ‘Elementary’, ‘Bolt-On’, ‘Ground-up’:

- Elementary (Few Interactions are Gameplay Like): here I mean visual elements, badges, and cute phraseology – in some cases you could think of these elemental gamification points as more funology than gamification – or at least at the intersection of the two;

- Bolt-On: implies a set of game elements that are more deeply related to games and gameplay, but are easy to add to a pre-existing development and which imply progress and reward, such as leaderboards, stages and levels, percentage complete, product configuration (mimicking, build your character), etc.; and

- Ground-up (All Interactions are Gameplay Like): here the game elements were planned from the start and were indivisible from the main development5152, or an existing development has evolved (exhibited emergent behaviour) from the use of the game elements into a system that is gameplay at the heart of its interaction scenarios.

It is difficult to try and describe the kinds of game activities which can be added at different stages, or the tools and techniques available as the area is still pretty new; however an understanding of play [Salen and Zimmerman, 2006] will help. Roughly, you should be thinking of, illustrations, comic elements, realer-than-life 3D renderings, and known badged content if you intend to add elemental gamification to your interaction. In this case, you are just wanting to enhance the visual look and feel of your system by using elements that will be familiar to gamers. You can see this in Boeing’s ‘New Airplane’ site which adds game like animated visuals to display its range of airliners (see Figure: Boeing’s ‘New Airplane’ Site).

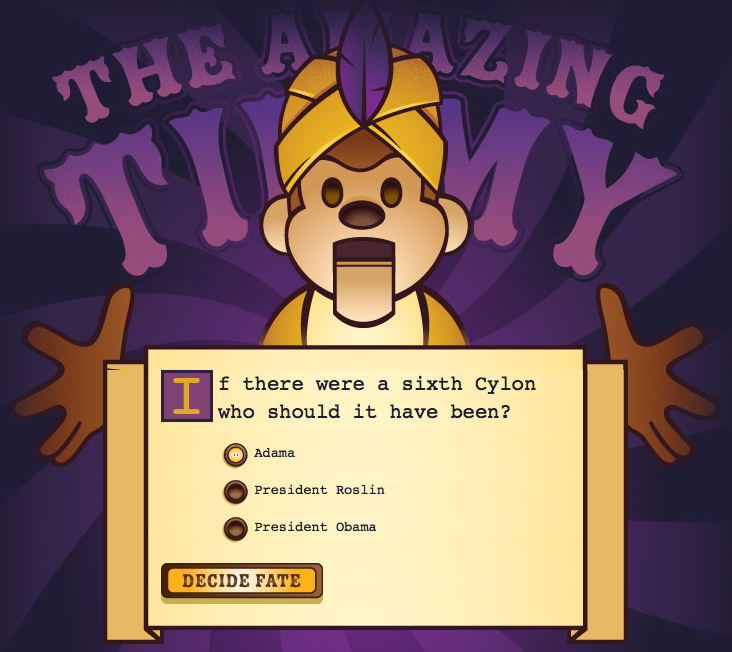

Now consider the next step to bolt on gamification, here additional elements are added to a pre-existing piece of software which mimic the structural elements of the game such as those associated with stages levels and leaderboards, etc., or whereby game like elements are added to increase the fun of interacting with your application. In this case consider the bolt-on gamification found in ThinkGeek, in which their reoccurring ‘fun’ character ‘Timmy the Monkey’ will decide the product you should purchase based on an answer to a question (see Figure: ThinkGeeks’s Timmy) – and visually mimicking a ‘Mechanical Turk’. Further, once you receive your purchase, a ‘Timmy’ sticker arrives with exhorting you to place your location on the map, cleverly conjoining the real and virtual worlds and making your virtual interactions in some way feel realer and personal (see Figure: ThinkGeeks’s Timmy Sticker Map).

Finally, we come to ground-up gamification in which the game elements are indivisible from the software system (its interactions, interfaces, and ethos) itself. In honesty, I’ve seen no really good examples of this, which are both game and non-game (if that makes any sense).

Now, you should also know that I’ve recently been having a conversation on twitter about gamification in the context of UX [Zichermann and Cunningham, 2011]. Now I see myself as far more circumspect than most, in that I see gamification as a convenient term to describe ‘digital umami’. The object of gamification is to make non-game software more engaging to users. So I think this is mainly only useful for applications that take relatively little interaction, and for systems that you may use a lot for a time but then stop – let’s call it transient interaction or use. Many gamification aficionados suggest that deeper gamification will have better results – although I’m not convinced how deep this goes; although to argue against myself I could propose that non-game applications that use game interactivity (not just visual design) dovetails more efficiently into the pre-learnt interaction characteristics and expectations already familiar to game-playing users.

Now if we transfer the positive aspects of gamification do we also transfer the negative characteristics too. So what are these? I think games can be loosely characterised as having the following (possibly negative) properties:

- Increasing difficulty of task completion: Games rely on the increasing difficulty – in other words as you increase levels you increase the difficulty to maintain interest. This suggests to me that loss of interest may very well occur in the gamified domains too – yet usability will always want to reduce difficulty not increase it;

- Goal attainment: Once your goal has been attained you mostly stop using the game – goal attainment finally leads to non-use. This may be a real problem in the gamified world unless the outcome can be varied such that it may not be attained on a regular basis – that being the case the ‘Real’ goal must never be the gamified goal – but rather a stop on the path the gamified goal – which is transient, can change, or attainment can fail – while the real goal is always attained;

- Limited scope for different kinds of interaction: Game interaction is limited as indicated by the simplicity of the controller. Complex touch screens as on EPOS systems or Keyboard support for general purpose computing do not exist. This suggests that rich interactivity may not be possible;

- Boredom: Games fail over time as people become bored with the game – once they ‘know’ it, they often leave it;

- Little keyboard input: Keyboard input does not occur much in gaming and so the level of jobs that can be accomplished through gamification may be reduced or be at least inappropriate; and

- Non-use in general: A game is finite.

Consider an investigation I recently performed, comprising two ATMs – one gamified, one not – testing both these systems I found that the non-gamified system took 23 seconds to dispense cash and the gamified on took 36 seconds. You don’t know this until you’ve used them once – but anecdotally, from a quick customer survey, people only choose the gamified one if there is no choice. In short, there may be many more problems for which we need to make accommodations. It seems that gamification may be useful to add a little spice but that without answers to the possible transfer of negative game playing traits the amount of value-added may turn out to be smaller than we imagine.

13.4 Collated Concepts of Engagement

Again, as with other collated material, the first thing to notice about concepts of engagement is that there are many of them and many different ones are proposed in many different sources. However there are differences from usability principles, in that – as with affective interaction – these are concepts and not principles. Remember, for the most part, the concepts coming up (even when I turn them into principles) are not likely to be directly testable. In fact, it is accepted within the domain that we probably won’t be able to check that a principle is present. But – again as with affective interaction – we may be able to check that the expected affect is absent.

Again, you will notice in Table: Collated Dynamic Concept that the left column describes the concept (these are sometimes used interchangeably between the different authors)53; while on the right side the authors are listed along with a footnote pointing to the text from which the concept is derived. In collating these concepts, I have not followed slavishly the nomenclature proposed by each author but have instead placed them in categories that I believe have the same conceptual value even if the naming of that concept does not follow that derived in the source.

Table: Collated Dynamic Concepts. Dynamic Concepts Collated by Source.

| Concepts | Appears in Source |

|---|---|

| Contextual Comms. | Duggan54. |

| Challenge | Anderson55; Csikszentmihalyi56. |

| Delight | Weinschenk57. |

| Drive | Paharia58. |

| Encourage | Paharia; Anderson. |

| Engage | Paharia; Anderson. |

| Enjoyable | Sharp; Rogers and Preece59; Weinschenk; Blythe60. |

| Entertaining | Sharp; Rogers and Preece; Csikszentmihalyi. |

| Enticement | Khaslavsky ** Shedroff61; Crane62. |

| Fun | Sharp; Rogers and Preece; Norman63. |

| Goals | Csikszentmihalyi. |

| Interest | Weinschenk. |

| Learning | Blythe. |

| Look and Feel (Game) | Crane. |

| Metaphor | Blythe. |

| Motivating | Sharp; Rogers and Preece; Crane; Duggan; Weinschenk; Anderson. |

| Narrative | Blythe. |

| Personalisation | Blythe. |

| Progression | Anderson; Csikszentmihalyi. |

| Rewards | Zichermann and Cunningham64; Duggan; Weinschenk; Anderson. |

| Social | Weinschenk; Anderson; Blythe. |

We can see that there are plenty of overlaps here which you should be aware of. Now, I’m going to discard some of these concepts because I think they are very niche because I don’t agree with them, because I don’t think they are helpful, or because there seems to be little consensus.

- ‘Challenge’. While challenge is a necessary component of play and games, it may not be useful in the non-game context, where I would see this as more related to goals, rewards, and motivation.

- ‘Delight’. Delight is difficult to quantify, as with most concepts here, however, it seems that the delight is better expressed in this case as enjoyment.

- ‘Drive’ + ‘Encourage’. Drive and encouragement both seem to fit together, however, I think they are better expressed as part of the motivation, reward, and goals aspects of non-game software.

- ‘Enticement’. We have already covered enticement in our affective principles.

- ‘Engage’. Engagement is, again, better represented in entertainment.

- ‘Interest’. interest, and maintaining that interest, seems to be a concept that arises from a good application of the others, and so trying to design for this may not be appropriate.

- ‘Learning’. We have already covered learing in our efficient principles.

- ‘Look and Feel (Game)’. The aesthetic qualities and the look and feel of the application have already been covered in our affective principles.

- ‘Metaphor’. We have already covered Metaphor in our efficient principles.

- ‘Personalisation’. We have already covered Personalisation in our effective principles.

- ‘Tangible Action’. We have already covered Tangible Action in our efficient principles.

Now the ‘carnage’ is over, let’s look at the concepts that will stay and/or be amalgamated:

- ‘Contextual Communication’. Contextual communication, indeed communications, in general, is important for many aspects of interaction and interactivity, including engagement, and is particularly related to group dynamics and social interaction.

- ‘Fun’ + ‘Enjoyable’ + ‘Entertaining’. These three concepts seem to go together in my opinion and so can be amalgamated into one principle (albeit incredibly difficult to test).

- ‘Motivation’ + ‘Reward’ + ‘Goals’. Again these three concepts are suitable for amalgamation and are mainly focused on dealing with propelling the user forward, based on some possible end-prize even if that prize is in some way intangible (such as an increase in status, etc.).

- ‘Narrative’ + ‘Progression’. Facilitating a user’s progression through interaction is of primary importance for good interactive dynamics. The progression may be reward based, based on fun, based on social and cultural norms, or indeed based on a combination of all three.

- ‘Social’. Social interactions are, again, very important for interaction and interface dynamics. This is because, as we have already seen, they dovetail into our natural social understanding.

13.5 Potted Principles of Dynamic User Experience

As with our previous discussions, when considering these upcoming principles, you must remember: that their presence cannot be individually or directly tested. That you are far more likely to be able to understand if they are not present, than if they are present; they contain many subjective words (such as Good) which make them difficult to quantify. And the engaging experiences to which they relate are likely to be subjective, temporal, cultural, and based in the user’s psychology.

13.5.1 Facilitate Social Dynamics

We’ve already discussed social dynamics, contextual communication, and group dynamics, and so I don’t propose to rehash that information here. Instead, think back to participatory design and your interactions with your user group, the dynamics of the focus groups, and the interaction between users. This kind of feeling is what you’re trying to create in users of your system. It may be that the system facilitates support via automated social methods, or by real social methods such as Microsoft’s ‘AskMSR’. However, in both cases, you should be trying to make sure that users have an understanding that there are other people also interacting with the system, and who are immediately available for support and task collaboration.

You should also not underestimate the effect language can have on an interaction and users emotional engagement with the system. You can support this by adding amusing phrases – or enabling users to add these phrases, ‘in’ jokes or business jargon (understood by the group) are also a good way of making users think of the systems as a ‘person’. In short, including the social aspects will help to tie better the real world to the virtual world in a more tangible way.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Do you include suitable functionality to facilitate collaboration?

- Are aspects such as social communication accounted for?

- Do you link the real and virtual to facilitate better user engagement?

- Can team or group members interact and support each other?

- Have you used language and terminology that users may find playful?

13.5.2 Facilitate Progression

Think back to all the fun and games that you have ever participated in. The commonality is that they all have a defined endpoint such that a reward can occur, they are based on some form of challenge, and that challenge can be mitigated by different levels (or mode) of ability. And, in most cases you have the ability to move through different phrases such that the challenge becomes increasingly difficult while still being tailored to your capabilities.

It may seem difficult to think about how this may be applied in a non-game like setting. However, it is possible with some judicious use of metaphor. Certainly, you could include the number of times, and the efficiency, a user has participated in a certain interactive task as an indicator of their expertise level. You could also move the user through a staged process, with a certain percentage completeness, to indicate moving to different levels or stages. And, finally, you may be able to display that user’s information once they’ve achieved the final level on some communal leader-board, or some resource that represents status by rewarding that user with a specific designation (such as novice, intermediate, improving, expert) of their user skills.

Indeed, this kind of progression facilitates motivation, but also allows you to harvest data in a way that is more acceptable to the user. It is far easier to harvest information that you might find useful to modify the user experience, from a user who is trying to increase their percentage information complete for a perceived virtual reward (ThinkGeek do this with Monkey Points), than it is just to ask for the information out-right. This kind of motivation also works in the real world, from a user experience point of view, this can be seen when trying to recruit participants for testing interactions. You’ll get very few people who contribute a free 15 minutes of their time, but give them a Snickers bar (which cost you fifty pence) and they will spend an hour telling you everything you ever wanted to know about their experiences with your development. All this works just because you provide motivation by goals or rewards and then facilitate the users progression (in some way) toward those goals and rewards.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Have you thought about attainment and goals, via stages and levels?

- Do you facilitate motivation and reward?

- Have you included a narrative flow through each interaction?

- Are there opportunities for friendly competition?

- Is progress also social?

13.5.3 Facilitate Play

The deeper aspects of play and gamification are incredibly difficult to define accurately and more work on the play and the translation of games into a non-game environment is required. You can add deeper elements that are specifically game based, but nothing like the normal interaction workflow, but progress the user along that workflow via some means which dovetails into their understanding of what the play is; by mimicking a game. We have already seen that this kind of thing works with ThinkGeeks’ ‘Mechanical Timmy’, ‘Google’ adds elements of fun by its random search, and ‘Ford’ allows you to customise a car in much the same way as you would customise a character in a game.

However you use these elements of play or game, you must make sure that they are in keeping with the interactive style and ethos of the interface and the interactions it facilitates; they should blend, add value, and assist the user does not jar the interactivity into a style other than that which was expected. In all cases this is subjective, and so – as with all of the principles within this section – you need to do thorough user validation before you can assert that your playful engagements are having a positive effect on the user experience.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Is the look and feel playful and game like?

- Have you included playful, and game like social elements?

- Will users leave with a feeling of fun and enjoyment?

- Are there playful games included, or game elements that make the interaction seem like a game, and not… work?

- Do the elements of play, included, really enhance the user experience?

Caveat

The main thing to remember is that adding engagement such as social or group dynamics, funology, or gamification may just not be the right thing to do for your development. Indeed, without extensive user testing adding these elements may harm the user experience and not enhance it; in some cases one person is ‘playful’ is another person’s ‘frustrating’. This is why one of the first principles we met is very important because by enabling flexibility within the user experience we can account for the subjective and individual desires of the user, allowing game like elements to those who will most benefit.

Likewise, including one or all of the principles listed above, may again not be appropriate. Some parts of each principle – in a mix–n–match fashion – may be appropriate, or indeed, a constrained set of principles (i.e. not all three) may also be more useful in enhancing the user experience. All this is based on your understanding of the application domain, as well is your understanding of how the principles should be applied, and the effects that those principles are having on the users.

Remember that as with all principles that relate to the subjective emotional, fun, and playful elements of development, you must pay specific attention to the target reactions of the users, and remember ‘good’ is not defined as more, but as the dead centre of the ‘Hebbian version’ of the ‘Yerkes Dodson Curve. Indeed, this view is also backed up by work within the emotional literature too.

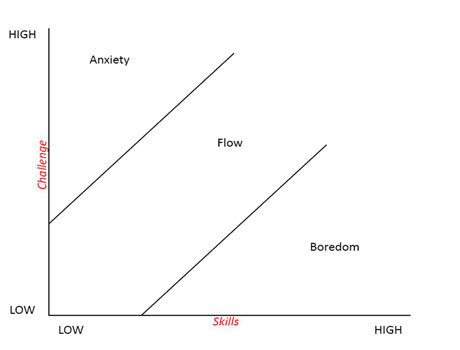

For instance, Csikszentmihalyi proposes a diagram (see Figure: Csikszentmihalyi’s ‘Flow’ Diagram) which places ‘skills’ against ‘challenge’. Here optimal flow is seen as an appropriate level of skill to an appropriate level of challenge, if there are too high a challenge and too low a skill-set than anxiety occurs; likewise if there is too low a challenge and to high skill-set then boredom occurs. This is similar to how we may think of naive and expert users and the system adaptations that should occur to support each.

In this case, adding too many opportunities for engagement may increase the boredom of the expert user who wishes to continue with their job as quickly as possible; conversely adding too few may make the naive user feel out of their depth. Of course, it may also be that expert users will also have better experiences with fun or playful dynamics as long as the task at hand is not time critical.

13.6 Summary

The benefits that may be derived from adding engaging aspects such as gamification, funology, and collaborative group elements are still very much tentative and anecdotal. However, it does seem clear that these kinds of elements are beneficial about the entire user experience, even if it is sometimes difficult to translate these engagement principles into live interfaces and interactions. While we can see that it may be useful to add elements of fun to the interface, to some extent the jury is still out on gamification. Indeed, you may notice that I have not touched on the wider topic of ‘Ground-up Gamification’ in which all interactions are gameplay like, specifically because its application is still contentious65. While there is much talk of this kind of interaction, and there are one or two (mainly website) instances of its occurrence, for the most part, it is my opinion that gamification from the ground-up equals a game, and is not equal a gamified non-game.

If you are finding it difficult to apply the principles as described in this chapter, I would suggest that you should still keep in mind the overriding design goals and intentions behind them. Think seriously about the fun elements of your design; make sure that you at least consider if game elements may be useful in helping – or encouraging – a user through a more complicated interaction; see if there is scope for collaboration and peer support within the system, and interactions, that you are building; and finally, try to the level of seduction and understanding of the humane aspects of the system which can so very often be ignored in the race for tangible effectiveness and efficiency.

In short, this chapter has been about the search for the intangibles that optimise our experiences and change a dry interface and interaction into one that joyful and is therefore actively sought. As a parting thought - which of these two pictures (Figure: Normal Egg Cup and Figure: Fun Egg Cups) of egg cups makes you smile?

13.6.1 Optional Further Reading

- [S. P. Anderson]. Seductive Interaction design: creating playful, fun, and effective user experiences. New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2011.

- [M. A. Blythe]. Funology: from usability to enjoyment, volume v. 3. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 2003.

- [K. Salen] and E. Zimmerman. The game design reader: a Rules of play anthology. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2006.

- [S. Weinschenk]. 100 things every designer needs to know about people. Voices that matter. New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2011.

- [G. Zichermann] and C. Cunningham. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps. 2011.