2. What is UX?

The human mind … operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Man cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but he certainly ought to be able to learn from it. In minor ways he may even improve, for his records have relative permanency. The first idea, however, to be drawn from the analogy concerns selection. Selection by association, rather than by indexing, may yet be mechanised. One cannot hope thus to equal the speed and flexibility with which the mind follows an associative trail, but it should be possible to beat the mind decisively in regard to the permanence and clarity of the items resurrected from storage.

The idea of associative memory, first proposed by ‘Vannevar Bush’ in his 1945 Atlantic Monthly article ‘As We May Think’, is credited with being the inspiration, and precursor, for the modern World Wide Web. But for most of his article, Bush was not concerned solely with the technical aspects of his ‘MEMEX’ system. Instead, as with most computer visionaries, he was more concerned with how the computer system and its interfaces could help humanity. He wanted us to understand that instead of fitting into the way a computer interacts and presents its data, the human cognitive and interactive processes should be paramount. In short, the computer should adapt itself to accommodate human needs; not the reverse.

2.1 HCI Foundations

Since the early days of computer science, with the move from punch cards to QWERTY keyboards. From “Doug Englebart’s” mouse and rudimentary hypertext systems, via work on graphical user interfaces at Xerox PARC. To the desire to share information between any computer (the World Wide Web), the human has been at the heart of the system. Human-computer interaction then has had a long history in terms of computer science but is relatively young as a separate subject area. In some ways, its study is indivisible from that of the components which it helps to make usable. However, as we shall see, key scientific principles different from most other aspects of computer science, support and underlay the area, and by implication its practical application as UX.

We will discuss aspects of the user experience such as rapid application development and agility, people and barriers to interactivity, requirements gathering, case studies and focus groups, stories and personas. We’ll look at accessibility guidelines, and usability principles, along with emotional design and human centred design. Finally, we’ll touch on the scientific method, experimentation, and inferential statistics. This seems like quite a lot of ground to cover, but it is very small in relation to the wider Human Factors / HCI domain. For instance we won’t cover:

- Adaptation;

- Customisation;

- Personalisation;

- Transcoding;

- Document Engineering;

- Cognitive Science;

- Neuroscience;

- Systems Behaviour;

- Interface Evolution;

- Emergent Behaviours;

- Application and User Agents;

- Widget Research & Design;

- Software Ethnography;

- Protocols, Languages, and Formats;

- Cognitive Ergonomics;

- Memory, Reasoning, and Motor Response;

- Learnability;

- Mental Workload;

- Decision-Making & Skilled Performance;

- Organisational Ergonomics;

- Socio-Technical Systems;

- Community Ergonomics;

- Cooperative Work;

- Inferential Statistics;

- Formal Experimental Methods; and

- Mobility and Ubiquity.

User experience (UX or UE) is often conflated with usability, but some would say takes-its-lead from the emerging discipline of experience design (XD). In reality, this means that usability is often thought of as being within the technical domain. Often being responsible for engineering aspects of the interface or interactive behaviour by building usability paradigms directly into the system. On the other hand, user experience is meant to convey a wider remit that does not just primarily focus on the interface but other psychological aspects of the use behaviour. We’ll talk about this in more detail later, because as the UX field evolves, this view has become somewhat out of date.

2.2 UX Emergence

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI or CHI in North America) is not a simple subject to study for the Computer Scientist. HCI is an interdisciplinary subject that covers aspects of computer science, ergonomics, interface design, sociology and psychology. It is for this reason that HCI is often misunderstood by mainstream computer scientists. However, if HCI is to be understood and correctly applied then an enormous amount of effort, mathematical knowledge, and understanding is required to both create new principles and apply those principles in the real world. As with other human sciences5, there are no 100% correct answers, everything is open to error because the human – and the environments they operate within – are incredibly complicated. It is difficult to isolate a single factor, and there are many extraneous hidden factors at work in any interaction scenario. In this case, the luxury of a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer is not available6.

The HCI field – of which UX is a part – is disparate, with each practitioner coming from a different specialism. In some cases psychology or ergonomics, in others sociology, for us, software engineering may be the primary specialisation, and in the context of UX, product designers also feature. This text has its roots firmly within the mainstream computer science domain, but it is aimed at a much broader audience. Therefore, whatever your background, you should find that this text covers the principle areas and key topics that you will need to understand, and manipulate the user experience. This means that, unlike other texts on UX, I will mainly be focusing on the tools and techniques required to understand and evaluate the interface and system. While I will spend one chapter looking at practice and engineering I feel it is more important to possess intellectual tools and skills. In this case, you will be able to understand any interface you work on as opposed to memorising a comprehensive treatise of the many different interfaces you may encounter now or in the future. This is not to say that the study of past work, or best practice, is without value, but it should not be the focus of a compressed treatise such as this. As technically literate readers, I expect that you will understand computational terminology and concepts such as input7 and output8 conventions; Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) conventions9; and other general terminology. I also assume that you will know next to nothing about UX or HCI.

HCI can normally be divided into three broad stages, that of the creation of the principles theories and methodologies, the application of those aspects into a development, and the testing of the outcomes of that development. While this may sound disjoint, techniques used for the investigation and discovery of problem areas in HCI are exactly the same techniques that can be used to evaluate the positive or negative outcomes of the application of those techniques within a more production focused setting. Normally this can be seen as pre-testing a system before any changes are made, the application of those changes in software or hardware, followed by a final post-testing phase that equates to an evaluation stage in which the human aspects of the interface can be scientifically derived. This pre-testing is however, often missed during ‘requirements analysis’, in some cases because there is no system to pre-test, and in others because there is an over-inflated value given to the implicit understanding of the system already captured.

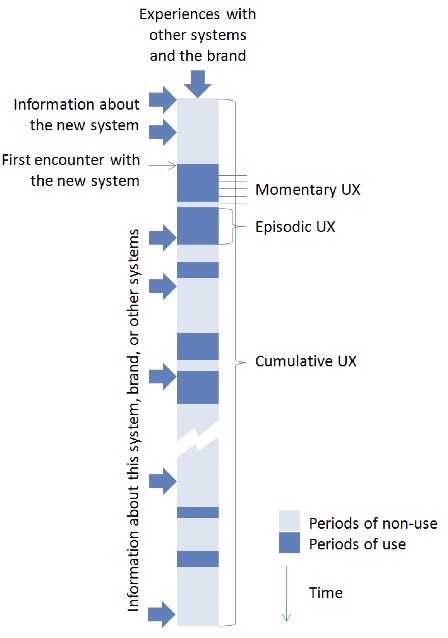

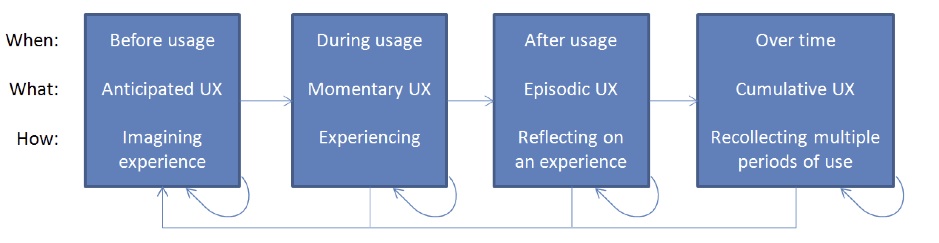

As a UX specialist, you will be concerned with the practical aspects surrounding the application of principles and guidelines into a development, and the testing of the outcomes of that development. This means that you will need to take into account the incremental nature of both the development and the experiences of the individual. Indeed we see that the user experience changes with time, and in some ways is linked with our memory and emotional state (see ‘Figure: UX Periods’ and ‘Figure: Time Spans of User Experience’ taken from [Roto et al., 2011]). In this way we can see that it is possible to counteract an initially bad systems experience, in a system that possibly must be complicated (such as an aircraft cockpit), by increasing the learnability of the controls and their layout. The initial momentary and episodic user experience may be complex – and in some cases seen as negative. However, the cumulative user experience may resolve as simple – equating to a positive user experience (especially in the case of the cockpit whereby the instrumentation, systems, and their layout are often replicated between aeroplanes, regardless of manufacturer or type).

We can, therefore, see that UX directly applies to condition ‘1’ indeed without access to, or the usability of, a system or component by a user this condition cannot be met. In the requirements analysis domain, work often progresses in a software engineering fashion. The methodology for requirements is coalesced around a set of modelling principles often initiated by a wave of interviews, discussions, systems analysis and modelling. In addition to focus-group participation leading to a formal specification or model of the systems and interaction requirement10 (requirements elicitation). These requirements have to be validated and modelled, however, as we shall see in later chapters, there are some problems with current approaches.

2.3 The Importance of UX

While the use of HCI as a tool for knowledge discovery is important, the significance of UX in the interface design and engineering domain should not be overlooked. User facing aspects of the interface are often created by software engineers or application programmers. While these are highly trained specialists, they are often less focused on aspects of user interaction than they are on the programme functionality and logic. In some cases, the end user is often seen as a silent participant in the application creation process and is usually only considered once the system aspects of the development have been created and tested. Indeed, in many cases there is an implicit idea that the user will need to conform to the requirements of the system, and the interface created by the developers. As opposed to the design of the system being a collaborative activity between user and engineer.

The focus of the UX specialist then is to make sure that the user is taken into account from the start. That participation occurs at all stages of the engineering process; that the resultant interface is fit for purpose in its usability and accessibility. And that, as much as possible, the interface is designed to fit the user and provoke a positive emotional response. By trying to understand user requirements, concerning both the system and the interface, the UX specialist contributes to the overall application design lifecycle. Often, in a very practical way which often belies the underlying scientific processes at work.

As we have seen, both requirements analysis and requirements elicitation are key factors in creating a usable system that performs the tasks required of it by the users and the commissioners of the system. Typically, however, requirements analysis and elicitation are performed by systems analysts as opposed to trained UX, human factors, or ergonomic specialists. Naturally, this means that there is often an adherence to set modelling techniques, usually adapted from the software architecture design process. This inflexibility can often be counter-productive because adaptable approaches of inquiry are often required if we are to better understand the user interaction. In reality, user experience is very similar to usability, although it is rooted within the product design community as opposed to the systems computing community of usability. Indeed, practical usability is often seen as coming from the likes of Nielson, Shneiderman, and lately Krug; while user experience came from the likes of Norman, Cooper, and Gerrett. Although, thinking also suggests these views are becoming increasingly popular11:

In this case, the usability specialist would often be expected to undertake a certain degree of software engineering and coding whereas the user experience specialist was often more interdisciplinary in focus. This meant that the user experience specialist might undertake the design of the physical device along with a study of its economic traits but might not be able to take that design to a hardware or software resolution. Indeed, user experience has been defined as:

Therefore, user experience is sometimes seen as less concerned with quantifiable user performance but more the qualitative aspects of usability. In this way, UX was driven by a consideration of the ‘moments of engagement’, known as ‘touchpoints’, between people and the ideas, emotions, and the memories that these moments create. This was far more about making the user feel good about the system or the interface as opposed to purely the utility of the interactive performance. User experience then fell to some extent outside of the technical remit of the computer science-trained HCI specialist.

While once correct these views do not represent the current state of UX in the computer engineering domain. In this case, it is the objective of this text to provide you with an overview of modern UX. Along with the kinds of tools and techniques that will enable you to conduct your own well-formed scientific studies of human-facing interfaces and systems within the commercial environment.

2.4 Modern UX

Defining UX is akin to walking on quicksand. There is no firm ground, and you’re likely to get mired in many unproductive debates – indeed, to me it seems debates on definitions are currently ‘stuck in the muck’.

But why is defining UX important or even necessary? Well, it must be necessary because everybody seems to be doing it. Indeed ‘All About UX’ (AllAboutUX) have collected many definitions (see the Appendix) with multiple and different perspectives. Further, it’s important because it provides a common language and understanding, and a solid, succinct definition enables everyone to know where they’re going and – in some regard – predicts the road ahead.

So why is it such a problem? It seems to me that there is no clear definition of user experience because it is not yet a distinct domain. Everyone is an immigrant to UX12, and there are no native UX practitioners or indeed first-generation educated practitioners who share a common understanding of what the phenomenon of UX actually is. This is always the case with new, cross-disciplinary, or combinatorial domains. But this does not help us in our efforts to describe the domain such that we all understand what it is we do, where it is we are going, and what falls inside or outside that particular area.

2.4.1 The UX Landscape

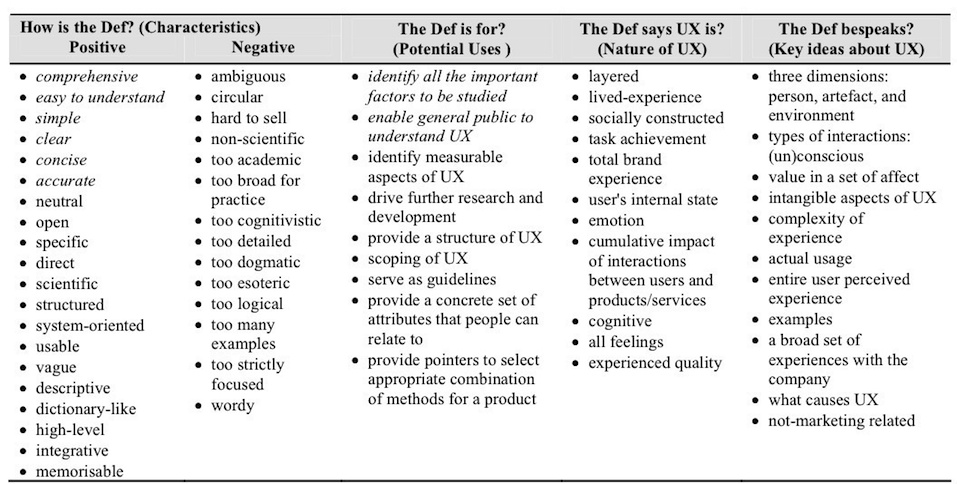

Why am I so concerned with Law’s CHI 2009 paper and the work coalescing around AllAboutUX? The positive point about both of these sources is that they are created based on a community understanding of the area, which implicitly defines the landscape of the user experience domain. In other definitions, created by experts in the field, you are asked to subscribe to the author’s interpretation. Both Law and AllAboutUX base their work on the populous view making little interpretation and allowing others to see the large differences within the comprehension, understanding, and definition of the UX field.

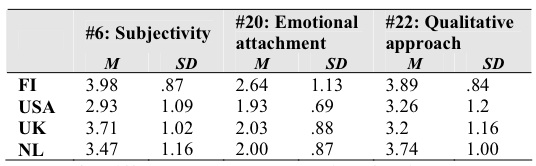

Indeed, purely by a cursory analysis of both sources we can see that there are major differences in understanding the subjectivity, emotional attachment, and qualitative approaches, even at the coarse-grained level of countries. Indeed, ‘Table: UX Country Differences’ shows us that the USA sees UX as less subjective than the other countries. However, all countries show a high degree of variance in the answers given. Further, all countries agree on the emotional attachment aspects of user experience but see this as being reasonably low as a factor in the UX landscape. However, all countries seem to agree that UX can be characterised by its qualitative approaches (as opposed to quantitative approaches) to understanding the experience.

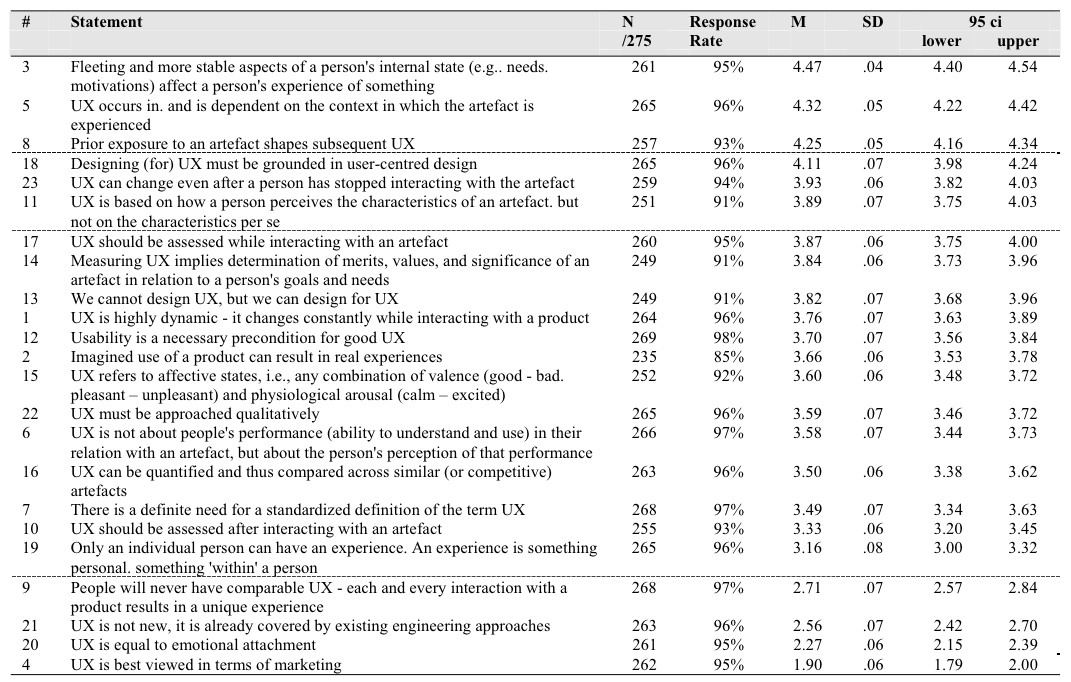

We can also infer (see tables taken from [Law et al., 2009]) that the community sees user experience as a lens into a person’s internal state. A state that affects their experience of the software or system and that this experience must take place within the presence of the software or system they are interacting with. And that it is dependent on their prior exposure to that software or system. Including it’s longitudinal aspects (see ‘Table: Twenty-three Statements About UX’), and that their responses are based on their ‘perceptions’ of the software or system they are interacting with — as opposed to the true properties of that system.

Further, the community sees that UX must be grounded in user centred design, we cannot design UX, but that we can design for UX. We can also see that the community do not think that UX is best viewed in terms of marketing. Or that UX is only equal to emotional responses (affective), or that UX is so individual that there will never be an overlap between people and products. Indeed, extrapolating from these results we can see that most UX specialists do not see the need for a high number of users in their testing and evaluation phases, or the need for quantitative statistical analysis. Instead, they prefer a low number of users combined with qualitative output and believe this can be extrapolated to a large population because people have comparable user experiences.

It seems that the most important parts of the UX landscape (see ‘Table: Twenty-three Statements About UX’), its nature and the ideas that are key to its understanding and application, can be summarised from the comments Law received. We could say that the nature of UX is multi-layered and concerns the user’s total experience (including their emotions and feelings) based on their current changeable internal state. UX is often socially constructed and represents the cumulative impact of interactions between users and the software or system, these interactions can be qualitatively and quantitatively measured. Key concepts through the UX landscape include the idea that not only the person, but also the artefact, and environment are equally important. And that interactions contain (un)conscious components, intangible aspects, actual and perceived interactions, and that the users’ entire and broad experiences are valuable.

2.4.2 Caveat

As we have already seen, everything we discover should be looked at with a critical eye, including definitions and understanding of the UX landscape. So why may there be a problem with the landscape we have built in the previous section. Indeed from an analysis of Law’s paper the responses from the community seemed to be reasonably strong — why should we, then, not believe them?

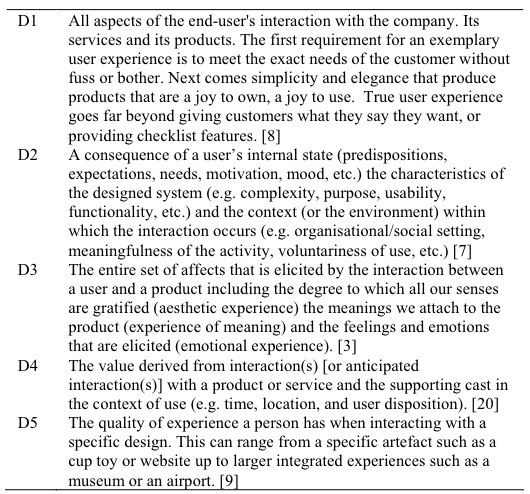

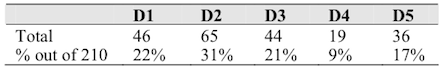

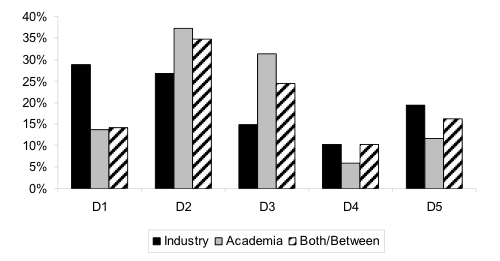

Firstly take a look at the demographics [Law et al., 2009]), it seems that this questionnaire was completed by far more industrial practitioners than academic ones — this may have skewed the results. Further, only 27 people said they were educated in art and design therefore we may not be getting a full view of the arts and humanities area — and how it is perceived from a non-technical viewpoint. One-hundred and twenty-three people said that they were interested in understanding UX to design better products, suggests that product designers views, and not software technologists, may have also skewed the results. In addition look at the countries, the authors say ‘[people from] 25 countries [responded], with larger groups of respondents from Finland (48), USA (43), UK (36), and the Netherlands (32)’ so obviously, the views from these countries will dominate. One of the main points to consider is the presumptions of the authors, as expressed in the five definitions used in the survey (see ‘Figure: UX Five Definitions’). The creation of these definitions implies the authors desire to elicit broad agreement (or not) and so their creation may introduce some degree of bias. And to some extent represents the authors view and implies that this view has some priority, as opposed a choice made by the UX participants.

This said, it is still my opinion that the authors have done everything possible to be inclusive and to represent the communities view of UX, however disjoint that may be, in an accurate and informative way. By investigating the domain more fully, taking into account other sources, we too can make more accurate appraisals of the UX landscape. And come to our own definition and understanding of what it means to be a UX specialist within that landscape.

As we have already discussed, the concept of UX is not nascent, indeed it has been around for 20-30 years. However, the formalization and professionalization of UX design as a distinct discipline are relatively recent developments.

The term “user experience” was first coined in the 1990s by Don Norman, a cognitive scientist who worked at Apple and other technology companies. Norman’s work on user-centered design and usability had a significant impact on the design industry, and his ideas helped establish the importance of designing products with the user in mind. However, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that UX design began to emerge as a distinct profession with its own set of practices and methodologies. As the importance of user-centered design became more widely recognized, companies began to hire dedicated UX designers and create UX teams to focus specifically on designing products that meet the needs of their users.

In this case, there are certain aspects of the field that are still evolving and can be considered nascent; which include:

- Emerging technologies: As new technologies like virtual and augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things continue to develop, UX designers will need to adapt their design methodologies to account for these new contexts and use cases.

- Inclusive design: While inclusive design has been a topic of discussion for many years, it is only recently that it has become a more prominent consideration in UX design. Inclusive design involves designing products and services that are accessible and usable by people of all abilities, ages, and backgrounds.

- Data-driven design: The use of data and analytics to inform design decisions is still a nascent aspect of UX design. While many companies are already using data to measure user behavior and improve their products, there is still much to be learned about how to effectively incorporate data into the design process.

- Ethical design: With the increasing attention being paid to data privacy and the ethical implications of technology, UX designers are increasingly being called upon to consider the ethical implications of their designs. This includes issues like data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the impact of technology on society as a whole.

- Cross-functional collaboration: While UX designers have long worked closely with other members of the design team, there is a growing recognition of the importance of cross-functional collaboration in UX design. This involves working closely with stakeholders from other areas of the business, such as product management, engineering, and marketing, to ensure that the user experience is aligned with business goals.

Overall, there are still many aspects of the discipline that are evolving and changing as technology, society, and business needs continue to evolve.

2.4.3 My View

I’ve previously written about my idea of UX. Having seen and read a number of definitions that suggest that UX is more about emotion and may be layered on top of other aspects of software engineering and development such as usability. However, the more I dig, the more I realise that I really do not believe any of the definitions as presented; either via the excellent work of Effie Law, or those parties coalesced around AllAboutUX and led primarily by Virpi Roto.

So what do I believe?

- I believe that UX is primarily about practice and application;

- I believe it is an umbrella term for a multitude of specialisms;

- I believe it is a phenomenon in that it exists and is observable;

- I believe that this phenomenon collects people, methods, tools, and techniques from the wider human factors domain and combines them for practical application;

- I do NOT believe that UX is a primary research domain but rather that UX is the practical application of a particular combination of tools, techniques, methods, principles, and mindset. And pulled in from primarily human factors and therefore psychology, social science, cognitive science, human-computer interaction, and secondarily product design, and marketing;

- I do believe that UX is a secondary field of study, if the narrow definition of UX is mainly concerned with emotional indicators is used. However, I believe this is more properly defined as ‘affective experience’; further

- I do not believe that UX is a ‘layer’ in the software artefact route to development but rather describes that software artefact in and holistic way.

Indeed, I see UX as a combination of the following properties13:

-

- Utility

- the software in development must be useful, profitable, or beneficial;

-

- Effective in Use

- the software must be successful in producing a desired or intended result (primarily the removal of technical barriers particularly about accessibility);

-

- Efficient in Use

- the software must achieve maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense (primarily the removal of barriers in relation to usability and interactivity);

-

- Affective in Use

- the software must support the emotional dimension of the experiences and feelings of the user when interacting; anticipating interaction, or when remembering interaction, with it; and

-

- Engaging in Use

- the software may exhibit an intangible dynamic deliciousness (umami) concerning the fun a system is to use.

So, my definition (and this may evolve) would be:

“User Experience is an umbrella term used to describe all the factors that contribute to the quality of experience a person has when interacting with a specific software artefact, or system. It focuses on the practice of user centred: design, creation, and testing, whereby the outcomes can be qualitatively tested using small numbers of users.”

In fact on 26th January 2014 it did evolve to:

“User Experience is an umbrella term used to describe all the factors that contribute to the quality of experience a person has when interacting with a specific software artefact, or system. It focuses on the practice of user centred: design, creation, and testing, whereby the outcomes can be qualitatively evaluated using small numbers of users.”

And again on 04th August 2022 to:

“User Experience is an umbrella term used to describe all the factors that contribute to the quality of experience a person has when interacting with a specific technical artefact, or system. It focuses on the practice of requirements gathering and specification, design, creation, and testing, integrating best practice, heuristics, and ‘prior-art’ whereby the outcomes can be qualitatively evaluated using small numbers of users, placing humans firmly in the loop”

2.5 Summary

As we can see, HCI is one of the most important aspects of computer science and application development. Further, UX is a mostly applied sub-domain of HCI. This is especially the case when that application development is focused on providing humans with access to the program functionality. But this is not the only concern of UX, indeed for many, it is the augmentation of the interactive processes and behaviours of the human in an attempt to deal with an ever more contemplated world that is the focus. This augmentation does not take the form of artificial intelligence or even cybernetics, but by enabling us to interact with computer systems more effectively, to understand the information that they are processing, and to allow us to focus more completely on the intellectual challenges; as opposed to those which are merely administrative or banal. Indeed, this objective has been Douglas C. Engelbart’s overarching aim since 1962:

“By augmenting human intellect we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems. Increased capability in this respect is taken to mean a mixture of the following: more-rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that previously was too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble.”

In the context of human factors, HCI is used in areas of the computer science spectrum that may not seem as though they obviously lend themselves to interaction. Even strategies in algorithms and complexity have some aspects of user dependency, as do the modelling and simulation domains within computational science.

In this regard, HCI is very much at the edge of discovery and the application of that discovery. Indeed, HCI requires a firm grasp of the key principles of science, scientific reasoning, and the philosophy of science. This philosophy, principles, and reasoning are required if a thorough understanding of the way humans interact with computers is to be achieved. In a more specific sense if you need to understand, and show, that the improvements made over user interfaces to which you have a responsibility, in fact, real and quantifiable.

In reality, it is impossible for a text such as this to give an all-encompassing in-depth analysis of the fields that are discussed; indeed this is not its aim. You should think of this text as a route into understanding the most complex issues of user experience from a practical perspective. But you should not regard it as a substitute for the most in-depth treatise presented as part of the further reading for each chapter. In reality, the vast majority of the work covered will enable you to both develop well-constructed interfaces and systems based on the principles of user experience; and run reasonably well-designed evaluations to test your developments.

2.5.1 Optional Further Reading

- [A. Dix] J. Finlay, G. Abowd, and R. Beale. Human-computer interaction. Prentice Hall Europe, London, 2nd ed edition, 1998.

- [C. Bowles] and J. Box. Undercover user experience: learn how to do great UX work with tiny budgets, no time, and limited support. Voices that matter. New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2011.

- [R. Unger] and C. Chandler. A project guide to UX design: for user experience designers in the field or in the making. Voices that matter. New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2009.

- [T. Erickson] and D. W. McDonald. HCI Remixed: essays on works that have influenced the HCI community. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2008.