5. Practical Ethics

A man without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world.

– Albert Camus

The primary purpose of evaluations involving human subjects is to improve our knowledge and understanding of the human environment including medical, clinical, social, and technological aspects. Even the best proven examples, theories, principles, and statements of relationships must continuously be challenged through evaluation for their effectiveness, efficiency, affectiveness, engagement and quality. In current evaluation and experimental practice some procedures, will by nature, involve a number of risks and burdens. UX specialists should be aware of the ethical, legal and regulatory requirements for evaluation on human subjects in their own countries as well as applicable international requirements. No national ethical, legal or regulatory requirement should be allowed to reduce or eliminate any of the protections for human participants which you as a professional UX practitioner are bound to follow, as part of your personal code of conduct.

Evaluation in the human science, of which UX is one example, is subject to ethical standards that promote respect for all human beings and protect their health and rights. Some evaluation populations are vulnerable and need special protection. The particular needs of the economically and medically disadvantaged must be recognised. Special attention is also required for those who cannot give, or refuse, consent for themselves, for those who may be subject to giving consent under duress, for those who will not benefit personally from the evaluation, and for those for whom the evaluation is combined with care.

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and torturing people under the guise of research.

However, the question for many UX specialists is, why do these standards, codes of conduct or practice, and duties of care exist. What is their point, why were they formulated, and what is the intended effect of their use?

5.1 The Need for Ethical Approaches

Rigourously structured hierarchical societies, as were common up until the 1960s, and indeed some may say are still common today, are often not noted for their inclusion or respect for all citizens. Indeed, one sided power dynamics have been rife in most societies. This power differential led to increasing abuse of those with less power by those with more power. This was no different within the scientific, medical, or empirical communities. Indeed, as the main proponents of scientific evaluation were, in most cases, economically established, educated, and therefore from the upper levels of society, abuses of human ‘subjects’4 became rife. Even when this abuse was conducted by proxy and there was no direct intervention of the scientist in the evaluation.

Indeed, these kinds of societies are often driven by persons who are in a position of power (at the upper levels) imposing their will on communities of people (at the lower levels). Further, these levels are often defined by both economic structure or some kind of inherited status or honour, which often means that citizens at the upper level have no concept of what it is to be a member of one of the lower levels. While it would be comforting to think that this only occurred in old European societies it would be ridiculous to suggest that this kind of stratified society did not occur in just about every civilisation, even if their formulation was based on a very specific and unique set of societal values.

In most cases, academic achievement provided a route into the upper levels of society, but also limited entry into those levels; as education was not widely available to an economically deprived population characteristic of the lower levels. In this case, societies worked by having a large population employed in menial tasks, moving to unskilled labour, to more skilled labour, through craftsmanship and professional levels, into the gentry, aristocracy, and higher levels of the demographic. In most cases, the lack of a meritocracy, and the absence of any understanding of the ethical principles at work, meant that the upper levels of society often regard the lower levels as a resource to be used.

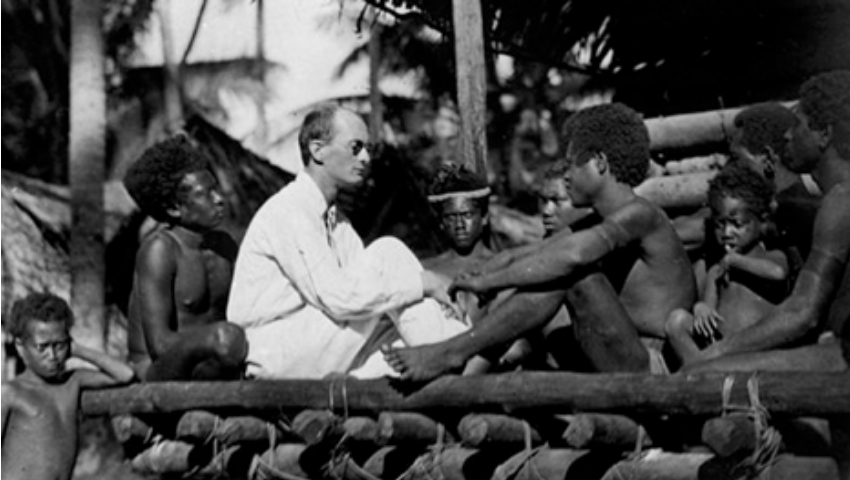

Many cases of abuse have been recorded in experimentation and investigations from the late 17th and early 18th centuries onwards. These abuses took place under the guise of furthering our knowledge of humankind and were often perpetrated against dominated populations. There are many recorded abuses of Australian aboriginal peoples, African peoples, and indigenous south American peoples, in the name of the advancement of our understanding of the world and the peoples within it. These abuses were not purely limited to the European colonies, but also occurred within the lower classes of European society; in some cases involving the murder (see Burke and Hare) and sale of subjects to complicit surgeons for anatomical investigation. Experimenters contented themselves with the rationale of John Stuart Mill, which suggests that experimental evaluation should do more good than harm, or that more people should benefit than suffer. However, there was no concept of justice in this initial rationale as the people who usually ended up suffering were the underprivileged and those who benefited were often the privileged minority.

The ethical rules that grew up in the late 1950s and 60s came about due to the widespread abuse of human subjects in 1940s Germany:

Once these abuses came to light, including the inhumane treatment meted out to adults and children alike, organisations such as the American Psychological Association and the American Medical Association began to examine their own evaluation practices. This investigation did not prove to be a pleasant experience, and while there were no abuses on the scale of the German Human Experiments it was found that subjects were still being badly treated even as late as the 1960s.

This growing criticism led to the need for ethical policies which would enable evaluation to be undertaken (there is clearly a benefit to society in scientific, medical, and clinical evaluation) but with a certain set of principles which ensured the well-being of the subjects. Obviously, a comprehensive ethical structure, to include all possible cases, is difficult to formulate at the first attempt. It is for this reason that there have been continual iterative revisions to many evaluation ethics guidelines. However, revisions have slowed and the key principles that have now become firm, should enable the UX specialist to design ethical studies taking into account the inherent human rights of all who participate in them.

5.2 Subjects or Participants?

You may be wondering why this overview matters to you as an UX specialist. In reality, ethics is a form of ‘right thinking’ which encourages us to moderate our implicit power over the people, and concepts, we wish to understand or investigate. You’ll notice that in all but the most recent ethical evaluation standards the term ‘subject’ is used to denote the human taking part in the experimental investigation. Indeed, I have deliberately used the term subject in all of my discussions up to this point, to make a very implicit way of thinking, explicit. The Oxford English Dictionary5 (OED) defines the term ‘subject’ variously as:

Of course the OED also describes a subject in a less pejorative manner as a person towards whom or which action, thought, or feeling is directed, or a person upon whom an experiment is made. Yet they also define the term ‘participant’, again variously, as:

Even taking the most neutral meaning of the term subject (in the context of human experimentation), and comparing it with that of the participant, a subject has an experiment made upon them, where as a participant shares in the experimental process. These definitions make it obvious that, even until quite recently, specialists considered the people partaking in their evaluation to be subjects of either the scientist or the experimentation. In reality, most specialists now use of the term participant to enable them to understand that, one-time subjects, are freely and informatively participating in their evaluation and should not be subjugated by that evaluation or the specialists undertaking it. Indeed, as we have seen in ‘evaluation methodologies’ (see Ethics), the more a human participant feels like a subject, the more they tend to agree with the evaluator. This means that bias is introduced into the experimental framework.

So then, by understanding that we have either evaluation participants, or respondents (a term often used, within sociology and the social sciences, to denote people participating in quantitative survey methods), we implicitly convey a level of respect and, in some ways, gratitude for the participation of the users. Understanding this key factor enables us to make better decisions with regard to participant recruitment and selection, assignment and control, and the definition and measurement of the variables. By understanding the worth of our participants we can emphasise the humane and sensitive treatment of our users who are often put at varying degrees of risk or threat during the experiment procedure. Obviously, within the UX domain these risks and threats are usually minimal or non-existent but by understanding that they may occur, and that a risk assessment is required, we are better able to see our participants as equals, as opposed to dominated subjects.

5.3 Keeping Us Honest

Good ethics makes good science and bad ethics makes bad science because the ethical process keeps us honest with regard to the kind of methodologies we are using and the kind of analysis that will be applied.

Ethics is not just about the participant but it is also about the outcomes of the evaluation being performed. Understanding the correct and appropriate methodology and having that methodology doubled checked by a evaluation ethics committee enables the UX practitioner to better account for all aspects of the evaluation design. As well as including that of the analysis it also encourages the understanding of how the data will be used and stored. As we have seen (see ‘Bedrock’), good science is based on the principle that any assertion made must have the possibility of being falsified (or refuted). This does not mean that the assertion is false, but just that it is possible to refute the statement. This refutability is an important concept in science, indeed, the term `testability’ is related, and means that an assertion can be falsified through experimentation alone. However, this possibility of testability can only occur if the collected data is available and the method is explicit enough to be understandable by a third party. Therefore, presenting your work to an ethics committee enables you to gain an understanding of the aspects of the methodology which are not repeatable without your presence. In addition, it also enables you to identify any weaknesses within the methodology or aspects, which are not covered within the write-up, but which are implicitly understood by yourself or the team conducting the evaluation.

In addition, ethical approval can help us in demonstrating to other scientists or UX specialists, that our methods for data gathering and analysis are well found. Indeed, presentation to an ethical committee is in some ways similar to the peer review process, in that any inadequacies within the methodology can be found before the experimental work commences, or sources of funding are approached. Indeed, the more ethical applications undertaken, the more likely it is that the methodological aspects of the work will become second nature and the evaluation design will in turn become easier.

It is therefore, very difficult to create a evaluation methodology which is inconsistent with the aims of the evaluation or inappropriate with regard to the human participants; and still have it pass the ethical vetting as applied by a standard ethics committee. Indeed, many ethical committees require that a technical report is submitted after the ethical procedures are undertaken so that an analysis of how the methodology was applied in real-life can be understood; and if there are any possible adverse consequences from this application. These kinds of technical reports often require data analysis and deviations from the agreed methodology to be accounted for. If not there may be legal consequences, or at the very least, problems with regard to the obligatory insurance of ethically approved procedures; for both the specific work and for future applications.

5.4 Practical Ethical Procedures

Before commencing any discussion regarding ethics and the human participant it may be useful to understand exactly what we mean by ethics. Here we understand that ethics relates to morals; a term used to describe the behaviour or aspects of the human character that is either good or bad, right or wrong, good or evil. Ethics then is a formulated way of understanding and applying the characteristics and traits that are either good or bad; in reality, the moral principles by which people are guided. In the case of human-computer interaction, ethics is the rules of conduct, recognised by certain organisations, which can be applied to aspects of UX evaluation. In the wider sense ethics and morals are sub-domains of civil, political, or international law [Sales and Folkman, 2000].

Ethical procedures then are often seen as a superfluous waste of time, or at best an activity in form filling, by most UX specialists. The ethical procedures that are required seem to be obtuse and unwieldy especially when there is little likelihood of danger, or negative outcomes, for the participants. The most practitioners reason that this is not, after all, a medical study or a clinical trial, there will be no invasive procedures or possibility of harm coming to a participant, so why do we need to undergo an ethical control?

This is entirely true for most cases within the user experience domain. However, the ethical process is a critical component of good evaluation design because it encourages the UX specialist to focus on the methodology and the analysis techniques to be used within that methodology. It is not the aim of the organisational ethical body to place unreasonable constraints on the UXer, but more properly, to make sure that the study designers possess a good understanding of what methodological procedures will be carried out, how they will be analysed, and how these two aspects may impact the human participants.

Ethics are critical component of good evaluation design because it encourages the UX specialist to focus on the methodology and the analysis techniques to be used within that methodology.

In reality then, ethical applications are focussed on ensuring due diligence, a form of standard of care relating to the degree of prudence and caution required of an individual who is under a duty of care. To breach this standard may end in a successful action for negligence, however, in some cases it may be that ethical approval is not required at all:

“Interventions that are designed solely to enhance the well-being of an individual patient or client and that have a reasonable expectation of success. The purpose of medical or behavioural practice is to provide diagnosis, preventative treatment, or therapy to particular individuals. By contrast, the term research designates and activities designed to develop or contribute generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships).”

In the case of UX then, the ethical procedure is far more about good evaluation methodology than it is about ticking procedural boxes.

As you already know, UX is an interdisciplinary subject and a relatively new one at that. This means that there are no ethical guidelines specifically to address the user experience domain. In this case, ethical principles and the ethical lead is taken from related disciplines such as psychology, medicine, and biomedical research. This means that, from the perspective of the UX specialist, the ethical aspects of the evaluation can sometimes seem like an incoherent ‘rule soup’.

To try and clarify the UX ethical situation I’ll be using principles guidelines and best practice taken from a range of sources, including:

- The American Psychological Association’s (APA), ‘Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct’;

- The United States Public Health Service Act (Title 45, Part 46, Appendix B), ‘Protection of Human Subjects’;

- The Belmont Report, ‘Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research’;

- The Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences, ‘International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies’; and finally

- The World Medical Association’s, ‘Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects’.

5.5 Potted Principles of Practical Ethical Procedures

As a responsible UX’er, you are required to conduct your evaluations following the highest scientific and ethical standards [Association, 2003]. In particular, you must protect the rights, interests and dignity of the human participants of the evaluation, and your fellow researchers themselves, from harm. The role of your Ethics body or committee is to ensure that any relevant experimentation or testing meets these high ethical standards, by seeking all information appropriate for ethical assessment, interviewing you as an applicant where possible, and coming to a judgement as to whether the proposed work should be: given ethical approval, refused ethical approval, or given approval subject specified conditions.

5.5.1 In brief…

We can see that the following list of key principles should be taken into account in any evaluation design be it in the field or within the user laboratory.

- Competence Keep up to date, know your limitations, ask for advice;

- Integrity Have no axe to grind or desired outcome;

- Science Follow the Scientific Method;

- Respect Assess your participant’s autonomy and capability of self-determination, treat participants as equals, ensure their welfare;

- Benefits Maximising benefits and minimising possible harms according to your best judgement, seek advice from your organisations ethics committee;

- Justice Research should be undertaken with participants who will benefit from the results of that research;

- Trust Maintain trust, anonymity, confidentiality and privacy, ensure participants fully understand their roles and responsibilities and those of the experimenter; and finally

- Responsibility You have a duty of care, not only to your participants, but also to the community from which they are drawn, and your community of practice.

Some practical considerations must be undergone when an application for ethical approval is being created. The questions are often similar over most ethical applications which involve UX. When creating any ethical procedure, you need to ask yourself some leading ethical questions to understand the various requirements of the ethical application. In some cases understanding these questions before you write your methodology is preferable, in this way you cannot be led down unethically valid path by understanding what changes you need to make to your evaluation work while you are designing it, and before it becomes too difficult to revise. Here I arrange aspects of the ethical procedure by ethical principles. These aspects describe the kinds of issues which should be considered when creating a methodology and cover the project: overview, participants, risks, safeguards, data protection and confidentiality, reporting arrangements, funding and sponsorship, and finally, conflicts of interest.

5.5.2 You Must Be Competent

- Other Staff: Assess, and suitable train, the other staff involved; and

- Fellow Researchers: Assess the potential for adverse effects, risks or hazards, pain, discomfort, distress, or inconvenience to the researchers themselves.

5.5.3 You Must Have Integrity

- Previous Participation: Will any research participants be recruited who are involved in existing evaluations or have recently been involved in any evaluation before recruitment? Assess the steps you will take to find out;

- Reimbursement: Will individual evaluation participants receive reimbursement of expenses or any other incentives or benefits for taking part in this evaluation? Assess if the UXers may change their attitudes towards participants, knowing this;

- Conflict of interest; Will individual evaluators receive any personal payment over and above normal salary and reimbursement of expenses for undertaking this evaluation? Further, will the host organisation or the researcher’s department(s) or institution(s) receive any payment of benefits more than the costs of undertaking the research? Assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest;

- Personal Involvement: Does the Chief UX Specialist or any other UXer/collaborator have any direct personal involvement (e.g. financial, share-holding, personal relationship, etc.) in the organisation sponsoring or funding the evaluation that may give rise to a possible conflict of interest? Again, assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest; and

- Funding and Sponsorship: Has external funding for the evaluation been secured? Has the external funder of the evaluation agreed to act as a sponsor, as set out in any evaluation governance frameworks? Has the employer of the Chief UX Specialist agreed to act as sponsor of the evaluation? Again, assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest.

5.5.4 Conform to Scientific Principles

- Objective: What is the principal evaluation question/objective? Understanding this objective enables the evaluation to be focused;

- Justification: What is the scientific justification for the evaluation? Give a background to assess if any similar evaluations have been done, and state why this is an area of importance;

- Assessment: How has the scientific quality of the evaluation been assessed? This could include independent external review; review within a company; review within a multi-centre research group; internal review (e.g. involving colleagues, academic supervisor); none external to the investigator; other, e.g. methodological guidelines;

- Demographics: Assess the total number of participants required along with their, sex, and the target age range. These should all be indicative of the target evaluation population;

- Purpose: State the design and methodology of the planned evaluation, including a brief explanation of the theoretical framework that informs it. It should be clear exactly what will happen to the evaluation participant, how many times and in what order. Assess any involvement of evaluation participants or communities in the design of the evaluation;

- Duration: Describe the expected total duration of participation in the study for each participant;

- Analysis: Describe the methods of analysis. These may be by statistical, in which case specify the specific statistical experimental design and justify why it was chosen, or using other appropriate methods by which the data will be evaluated to meet the study objectives;

- Independent Review: Has the protocol submitted with this application been the subject of review by an independent evaluator, or UX team? This may not be appropriate but it is advisable if you are worried about any aspects; and

- Dissemination: How is it intended the results of the study will be reported and disseminated? Internal report; Board presentation; written feedback to research participants; presentation to participants or relevant community groups; or by other means.

5.5.5 Respect Your Participants

- Issues: What do you consider to be the main ethical issues that may arise with the proposed study and what steps will be taken to address these? Will any intervention or procedure, which would normally be considered a part of routine care, be withheld from the evaluation participants. Also, consider where the evaluation will take place to ensure privacy and safety;

- Termination: Assess the criteria and process for electively stopping the trial or other evaluations prematurely;

- Consent: Will informed consent be obtained from the evaluation participants? Create procedures to define who will take consent and how it will be done. Give details of how the signed record of consent will be obtained and list your experience in taking consent and of any particular steps to provide information (in addition to a written information sheet) e.g. videos, interactive material. If participants are to be recruited from any of the potentially vulnerable groups, assess the extra steps that will be taken to assure their protection. Consider any arrangements to be made for obtaining consent from a legal representative. If consent is not to be obtained, think about why this is not the case;

- Decision: How long will the participant have to decide whether to take part in the evaluation? You should allow an adequate time;

- Understanding: Implement arrangements for participants who might not adequately understand verbal explanations or written information given in English, or who have special communication needs (e.g. translation, use of interpreters, etc.);

- Activities: Quantify any samples or measurements to be taken. Include any questionnaires, psychological tests, etc. Assess the experience of those administering the procedures and list the activities to be undertaken by participants and the likely duration of each; and

- Distress: Minimise, the need for individual or group interviews/questionnaires to discuss any topics or issues that might be sensitive, embarrassing or upsetting; is it possible that criminal or other disclosures requiring action could take place during the study (e.g. during interviews/group discussions).

5.5.6 Maximise Benefits

- Participants: How many participants will be recruited? If there is more than one group, state how many participants will be recruited in each group. For international studies, say how many participants will be recruited in the UK and total. How was the number of participants decided upon? If a formal sample size calculation was used, indicate how this was done, giving sufficient information to justify and reproduce the calculation;

- Duration: Describe the expected total duration of participation in the study for each participant;

- Vulnerable Groups: Justify their inclusion and consider how you will minimise the risks to groups such as: children under 16; adults with learning difficulties; adults who are unconscious or very severely ill; adults who have a terminal illness; adults in emergency situations; adults with mental illness (particularly if detained under mental health legislation); adults with dementia; prisoners; young offenders; adults in Scotland who are unable to consent for themselves; those who could be considered to have a particularly dependent relationship with the investigator, e.g. those in care homes, students; or other vulnerable groups;

- Benefit: Discuss the potential benefit to evaluation participants;

- Harm: Assess the potential adverse effects, risks or hazards for evaluation participants, including potential for pain, discomfort, distress, inconvenience or changes to lifestyle for research participants;

- Distress: Minimise, the need for individual or group interviews/questionnaires to discuss any topics or issues that might be sensitive, embarrassing or upsetting; is it possible that criminal or other disclosures requiring action could take place during the study (e.g. during interviews/group discussions).

- Termination: Assess the criteria and process for electively stopping the trial or other evaluation prematurely;

- Precautions: Consider the precautions that have been taken to minimise or mitigate any risks;

- Reporting: instigate procedures to facilitate the reporting of adverse events to the organisational authorities; and

- Compensation: What arrangements have been made to provide indemnity and compensation in the event of a claim by, or on behalf of, participants for negligent harm and non-negligent harm;

5.5.7 Ensure Justice

- Demographics: Assess the total number of participants required along with their, sex, and the target age range. These should all be indicative of the population the evaluation will benefit;

- Inclusion: Justify the principal inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- Recruitment: How will potential participants in the study be (i) identified, (ii) approached and (iii) recruited;

- Benefits: Discuss the potential benefit to evaluation participants;

- Reimbursement: Assess whether individual evaluation participants will receive reimbursement of expenses or any other incentives or benefits for taking part in this evaluation; and

- Feedback: Consider making the results of evaluation available to the evaluation participants and the communities from which they are drawn.

5.5.8 Maintain Trust

- Monitoring: Assess arrangements for monitoring and auditing the conduct of the evaluation (will a data monitoring committee be convened?);

- Confidentiality: What measures have been put in place to ensure confidentiality of personal data? Will encryption or other anonymising procedures be used and at what stage? Carefully consider the implications involving any of the following activities (including identification of potential research participants): examination of medical records by those outside the medical facility, such as UX specialists working in bio-informatics or pharmacology; electronic transfer by magnetic or optical media, e-mail or computer networks; sharing of data with other organisations; export of data outside the European Union; use of personal addresses, postcodes, faxes, e-mails or telephone numbers; publication of direct quotations from respondents; publication of data that might allow identification of individuals; use of audio/visual recording devices; storage of personal data as manual files including, home or other personal computers, university computers, private company computers, laptop computers

- Access: Designate someone to have control of and act as the custodian for the data generated by the study and define who will have access to the data generated by the study.

- Analysis: Where will the analysis of the data from the study take place and by whom will it be undertaken?

- Storage: How long will the data from the study be stored, and where will this storage be; and

- Disclosure: Create arrangements to ensure participants receive any information that becomes available during the research that may be relevant to their continued participation.

5.5.9 Social Responsibility

- Monitoring: Assess arrangements for monitoring and auditing the conduct of the evaluation (will a data monitoring committee be convened?);

- Due Diligence: Investigate if a similar application been previously considered by an Ethics Committee in the UK, the European Union or the European Economic Area?

- Disclosure: State if a similar application been previously considered by an Ethics Committee in the UK, the European Union or the European Economic Area. What was the result of the application, how does this one differ and state why you are (re)submitting it;

- Feedback: Consider making the results of evaluation available to the evaluation participants and the communities from which they are drawn.

5.6 Summary

Remember, Ethical applications are focussed on ensuring due diligence. Simply this is a standard of care relating to the degree of prudence and caution required of UX specialist who is under a duty-of-care. As a responsible UX’er, you are required to conduct your evaluation by the highest ethical standards. In particular, you must protect the rights, interests and dignity of the human participants of the evaluation, and your fellow UX’ers, from harm.

To help you accomplish this duty-of-care, you should ask yourself the following questions at all stages of your evaluation design and experimentation: (1) Is the proposed evaluation sufficiently well designed to be of informational value? (2) Does the evaluation pose any risk to participants by such means as the use of deception, of taking sensitive or personal information or using participants who cannot readily give consent? (3) If the risks are placed on participants, does the evaluation adequately control those risks by including procedures for debriefing or the removal or reduction of harm, guaranteeing through the procedures that all information will be obtained anonymously or if that is not possible, guaranteeing that it will remain confidential and providing special safeguards for participants who cannot readily give consent? (4) Have you included a provision for obtaining informed consent from every participant or, if participants cannot give it, from responsible people acting for the benefit of the participant? Will sufficient information be provided to potential participants so that they will be able to give their informed consent? Is there a clear agreement in writing between the evaluation and potential participants? The informed consent should also make it clear that the participant is free to withdraw from an experiment at any time. (5) Have you included adequate feedback information, and debriefing if deception was included, to be given to the participants at the completion of the evaluation? (6) Do you accept full responsibility for safety? (7) Has the proposal been reviewed and approved by the appropriate review board? As we can see these checks cover the range of the principles informing the most practical aspects of human participation in ethically created evaluation projects. By applying them, you will be thinking more holistically about the ethical processes at work within your evaluations, especially if you quickly re-scan them at every stage of the evaluation design. Finally, this is just an abbreviated discussion of ethics; there are plenty more aspects to consider, and some of the most salient points are expanded upon in the Appendix.

5.6.1 Optional Further Reading

- [Barry G. Blundell]. Ethics in Computing, Science, and Engineering: A Student’s Guide to Doing Things Right. N.p.: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- [Nina Brown], Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González. Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology 2nd edition 2020

- [Rebecca Dresser]. Silent Partners: Human Subjects and Research Ethics. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- [Joseph Migga Kizza]. Ethics in Computing: A Concise Module. Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- [Bronislaw Malinowski]. Argonauts of the Western Pacific (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1922), 290.

- [Perry Morrison] and Tom Forester. Computer Ethics: Cautionary Tales and Ethical Dilemmas in Computing. United Kingdom: MIT Press, 1994.

- [David B. Resnik]. The Ethics of Research with Human Subjects: Protecting People, Advancing Science, Promoting Trust. Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- [B. D. Sales] and S. Folkman. Ethics in research with human participants. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., 2000.

5.6.2 International Standards

- [APA] Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychological Association, 2003.

- [BELMONT] The Belmont Report, ‘Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research’.

- [CIOMS] The Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences, ‘International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies’.

- [HS-ACT] The United States Public Health Service Act (Title 45, Part 46, Appendix B), ‘Protection of Human Subjects’.

- [HELSINKI] The World Medical Association’s, ‘Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects’.