Part II: Designing the User Experience

4. People are Complicated!

Complexity is your enemy. Any fool can make something complicated. It is hard to make something simple.

– Richard Branson

The key aspect of user experience is its focus on making a system more humane. This means tailoring the system to the user, and not expecting the user to happily conform to the system. We can only achieve this by understanding how humans sense and perceive the outside environment (the system or interface), process and store this knowledge. Making use of it either directly or in the future, and based on past and current knowledge exert control over an external environment (again, in this case, the system or interface).

4.1 UX is Everywhere

User experiences occur in many contexts and over many domains. This variety sometimes makes it difficult to ‘pigeon hole’ UX as one specific thing - as we have discussed - UX is the broad term used to describe the experience of humans with computers both at the interface and system level.

Indeed, the ACM and the IEEE Curriculum ‘Subjects Coverage’ - lists Human Factors as occurring in the following domains:

- AL/Algorithmic Strategies

- NC/Networked Applications

- HC/Foundations

- HC/Building GUI Interfaces

- HC/User Centred Software Evaluation

- HC/User Centred Software Development

- HC/GUI Design

- HC/GUI Programming

- HC/Multimedia And Multimodal Systems

- HC/Collaboration And Communication

- HC/Interaction Design For New Environments

- GV/Virtual Reality

- IM/Hypermedia

- IM/Multimedia Systems

- IS/Fundamental Issues

- NC/Multimedia Technologies

- SE/Software Verification Validation

- CN/Modelling And Simulation

- SP/Social Context

- SP/Analytical Tools

- SP/Professional Ethics

- SP/Philosophical Frameworks

Subject Key: Algorithms and Complexity (AL); Net-Centric Computing (NC); Human–Computer Interaction (HC); Graphics and Visual Computing (GV); Intelligent Systems (IS); Information Management (IM); Software Engineering (SE); Computational Science (CN); Social and Professional Issues (SP).

However, more broadly this is often referred to as human factors that suggest an additional non-computational aspect within the environment; affecting the system or interaction indirectly. This leads on to the discipline of ergonomics, also known as human factors, defined as … ‘the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design in order to optimise human well-being and overall system performance.’ At an engineering level, the domain may be known as user experience engineering.

However, in all cases, the key aspect of Human Factors and its application as user experience engineering is the focus on making a system more humane (see Figure: Microsoft Active Tiles). There is no better understanding of this than that possessed by ‘Jef Raskin’, creator of the Macintosh GUI for Apple Computer; inventor of SwyftWare via the Canon Cat; and author of ‘The Humane Interface’ [Raskin, 2000]:

“Humans are variously skilled and part of assuring the accessibility of technology consists of seeing that an individual’s skills match up well with the requirements for operating the technology. There are two components to this; training the human to accommodate the needs of the technology and designing the technology to meet the needs of the human. The better we do the latter, the less we need of the former. One of the non-trivial tasks given to a designer of human–machine interfaces is to minimise the need for training.

Because computer-based technology is relatively new, we have concentrated primarily on the learnability aspects of interface design, but the efficiency of use once learning has occurred and automaticity achieved has not received its due attention. Also, we have focused largely on the ergonomic problems of users, sometimes not asking if the software is causing ‘Cognetic’ problems. In the area of accessibility, efficiency and Cognetics can be of primary concern.

For example, users who must operate a keyboard with a pointer held in their mouths benefit from specially designed keyboards and well-shaped pointers. However well-made the pointer, however, refined the keyboard layout, and, however, comfortable the physical environment we have made for this user, if the software requires more keystrokes than necessary, we are not delivering an optimal interface for that user. When we study interface design, we usually think regarding accommodating higher mental activities, the human capabilities of conscious thought and ratiocination.

Working with these areas of thought bring us to questions of culture and learning and the problems of localising and customising interface designs. These efforts are essential, but it is almost paradoxical that most interface designs fail first to assure that the interfaces are compatible with the universal traits of the human nervous system, in particular, those traits that are sub-cortical and that we share with other animals. These characteristics are independent of culture and learning, and often are unaffected by disabilities.

Most interfaces, whether designed to accommodate accessibility issues or not, fail to satisfy the more general and lower-level needs of the human nervous system. In the future, designers should make sure that an interface satisfies the universal properties of the human brain as a first step to assuring usability at cognitive levels.”

In the real world, this means that the UX specialist can be employed in many different jobs and many different guises; being involved in the collection of data to form an understanding of how the system or interface should work. Regardless of the focus of the individual project, the UX specialist is concerned primarily with people and the way in which they interact with the computational system.

4.2 People & Computers

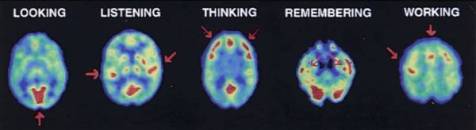

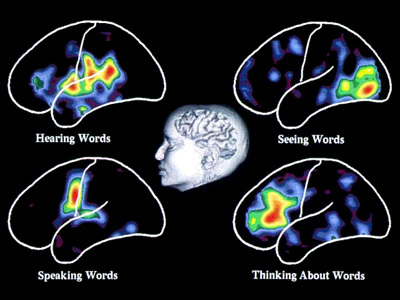

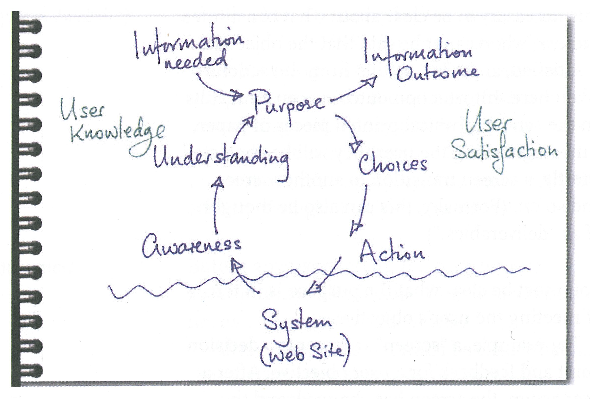

Understanding how humans take in information, understand and learn from this information, and use it to guide their control of the outside world, is key to understanding their experiences [Weinschenk, 2011] (see PET scans in Figure: PET studies of glucose metabolism). Here we are not concerned directly with the anatomical, physiological, or psychological aspects of these processes (there are many in-depth treatise that address these areas), but instead, look at them at the point where user meets software or device. In this case we can think, simplistically, that humans sense and perceive the outside environment (the system or interface), process and store this knowledge making use of it either directly or in the future. Moreover, based on both past and current knowledge exert control over an external environment (again, in this case, the system or interface) [Bear et al., 2007].

4.2.1 Perceiving Sensory Information

Receiving sensory information can occur along some different channels. These channels relate to the acts of: seeing (visual channel), hearing (auditory channel), smelling (olfactory channel), and touching (somatic/haptic channel). This means that each of these channels could, in effect, be used to transmit information regarding the state of the system or interface. It is important then, to understand a few basic principles of these possible pathways for the transmission of information from the computer to the human.

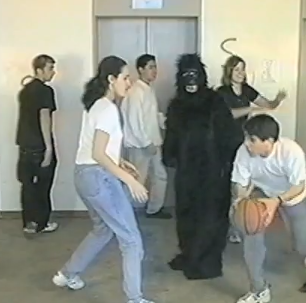

However, before we begin, remember back to our previous discussion – and concerning ‘Figure: Basketball’ – examining Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris’ experiments which required you to count passes of a Basketball. Well, this phenomenon is just one example of the complexities involved in understanding users, their perception, and their attention. The phenomenon exhibited is known as ‘Inattention blindness’, ‘attention blindness’, or ‘perception blindness’ and relates to our expectations, perception, and locus of attention. Simply, inattention blindness describes our ability to notice something that is in plain view and has been seen. This normally occurs when we are not expecting the stimulus to occur – why would a Gorilla be moonwalking in a basketball match? If we do not think it should be there, our brains compensate for the perceptual input by not cognitively registering that stimuli. However, there are plenty of other tests that also show this phenomenon. Moreover, there are some different explanations for the why it occurs. As you’ve just read, I prefer the ‘Expectation’ explanation, but others suggest: conspicuity, stimuli may be inconspicuous and therefore not seen as important. Mental workload, we may be too busy focused on another task to notice a stimuli, or capacity this is really the locus of attention explanation; as we shall see later in on. In reality, I expect that there is some combination of each explanation at play, but the point is that the phenomenon itself is not what we would expect, and we don’t exactly know why or how it occurs. Keep this level of uncertainty in mind as you read more and as you start you work in the UX domain.

4.2.1.1 Visual Interaction

Visual interaction design is determined by the arrangement of elements or details on the interface that can either facilitate or impede a user through the available resources. This is because the amount of information within the interface that reaches our eyes is far greater than our brain can process, and it is for this reason that the visual channel and, therefore, visual attention is key to good design. Selective visual attention is a complex action composed of conscious and subconscious processes in the brain that are used to find and focus on relevant information quickly and efficiently. There are two general visual attention processes, bottom-up and top-down, which determine where humans next locate their attention. Bottom-up models of visual attention suggest that low-level salient features, such as contrast, size, shape, colour, and brightness correlate well with visual interest. For example, a red apple (a source of nutrition) is more visually salient, and, therefore, attractive, than the green leaves surrounding it. Top-down models, on the other hand, explain visual search driven by semantics, or knowledge about the environment: when asked to describe the emotion of a person in a picture, for instance, people will automatically look to the person’s face.

Both forms of visual attention inevitably play a part in helping people to orientate, navigate and understand the interface. Bottom-up processing allows people to quickly detect items, such as bold text and images, which help to explain how the interface is organised. It also helps people to group the information into ‘sections’, such as blocks of text, headings, and menus. Top-down processing enables people to interpret the information using prior knowledge and heuristics. For example, people may look for menus at the top and sides of the interface, and main interface components in the middle.

It can be seen from eye tracking studies that users focus attention sequentially on different parts of the interface and that computational models have been successfully employed in computer graphics to segment images into regions that the user is most likely to focus upon. These models are based upon a knowledge of human visual behaviour and an understanding of the image in question. Indeed, studies exist which record user’s eye movements during specific interactive tasks, to find out those features within and interface design that were visited, in which order and where ‘gaze hotspots’ were found. In these data, we can see an association between the interface components and eye-gaze, but not one as simple as ‘the user looked at the most visually obvious interface features. Indeed, sometimes large-bold-text next to an attention grabbing feature, such as an image, was fixated upon. However, we can deduce that, for instance, the information in some text may not itself draw a user’s attention but ideally has some feature nearby which do. This idea is supported by other studies that try to create interface design metrics that predict whether an interface is visually complex or not. These studies relate to interface design with complexity explaining that the way an interaction is perceived depends on the way the interface itself is designed and what components are used.

Through an understanding of the visual channel we can see that there are levels of granularity associated with visual design. This granularity allows us to understand a large visual rendering by segmentation into smaller more manageable pieces or components. Our attention moves between these components based on how our visual attention relates to them, and it is this knowledge of how the visual channel works, captured as design best practice, which allows designers to build interfaces that users find interesting and easy to access. The visual narrative the designer builds for the observer is implicitly created by the visual appearance (and, therefore, attraction) of each visual component. It is the observers focus, or as we shall see, the locus of attention, which enables this visual narrative to be told.

4.2.1.2 The Auditory Channel

The Auditory channel is the second most used channel for information input, and as highly interrelated with the visual channel, however, auditory input has some often overlooked advantages. For instance, reactions to auditory stimuli have been shown to be faster, in some cases, than reactions to visual stimuli. Secondly, the use of auditory information can go some way towards reducing the amount of visual information presented on screen. In some regard, this reduces possible information overload from both interface components and aspects of the interaction currently being performed. The reduction in visual requirements means that attention can be freed to stimuli that are best handled visually, and means that auditory stimulation can be tailored to occur within the part of the interaction to which it is best suited. Indeed, the auditory channel is, often, under-used in relation to standard interface components. In some cases, this is due to the need for an absence of noise pollution within the environment. We can see that consistent sound or intermittent sound can often be frustrating and distracting to computer users within the same general environment; this is not the case with visual stimuli that can be specifically targeted to the principal user. Finally, and in some cases most importantly, sound can move the users attention, and focus it to a specific spatial location. Due to the nature of the human auditory processing system, studies have found that using different frequencies similar to white noise are most effective in attracting attention. This is because human speech and communication occur using multiple frequencies whereas single frequencies with transformations such as sirens or audible tones may jar the senses but are more difficult to locate spatially.

Obviously, sound can be used for many different and complementary aspects of the user interface. However, the HCI specialist must consider the nature of the sound and its purpose. In addition, interfaces that rely only on sound, with no additional visual cues, may mean the interface becomes inflexible in environments where the visual display is either obscured or not present at all. Sound can be used to transmit speech and non-speech. Speech would normally be via text to speech synthesis systems. In this way, the spoken word can be flexible, and the language of the text can be changed to facilitate internationalisation. One of the more interesting aspects of non-speech auditory input is that of auditory icons and ‘Earcons’. Many systems currently have some kind of auditory icon, for instance, the deletion of files from a specific directory is often accompanied by sound used to convey the deletion, such as paper being scrunched. Earcons are slightly more complicated as they involve the transmission of non-verbal audio messages to provide information to the user regarding some type of computer object, operation, or interaction. Earcons, use a more traditional musical approach than auditory icons and are often constructed from individual short rhythmic sequences that are combined in different ways. In this case, the auditory component must be learned as there is no intuitive link between the Earcon and what it represents.

4.2.1.3 Somatic

The term ‘Somatic’ covers all types of physical contact experienced in an environment, whether it be feeling the texture of a surface or the impact of a force. Haptics describe how the user experiences force or cutaneous feedback when they touch objects or other users. Haptic interaction can serve as both a means of providing input and receiving output and has been defined as ‘The sensibility of the individual to the world adjacent to his body by use of his body’. Haptics are driven by tactile stimuli created by a diverse sensory system comprising receptors covering the skin, and processing centres in the brain, to produce the sensory modalities such as touch and temperature. When a sensory neuron is triggered by a specific stimulus, a neuron passes to an area in the brain that allows the processed stimulus to be felt at the correct location. It can, therefore, be seen, that the use of the haptic channel for both control and feedback can be important especially as an aid to other sensory input or output. Indeed, haptics and tactility have the advantage of making interaction seem realer, which accounts for the high use of haptic devices in virtual and immersive environments.

4.2.1.4 The Olfactory System

The Olfactory system enables us to perceive smells. It may, therefore, come as a surprise to many studying UX that there has been some work investigating the use smell as a form of sensory input directly related to interaction (notably from [Brewster et al., 2006]). While this is a much under-investigated area, certain kinds of interface can use smell to convey an extra supporting component to the general, and better understood, stimuli of sound and vision. One of the major benefits of smell is that it has a close link with memory, in this case, smell can be used to assist the user in finding locations that they have already visited, or indeed recognise a location they have already been to within the interactive environment. Indeed, it seems that smell and taste [Narumi et al., 2011] is particularly effective when associated with image recognition, and can exist in the form of an abstract smell, or a smell that represents a particular cue. It is, however, unlikely, as a UX’er, that smell will be used in any large way in the systems you are designing, although it may be useful to keep smell in mind if you are having particular problems with users forgetting aspects of previously learnt interaction.

4.2.2 Thinking and Learning

The next part of the cycle is how we process, retain, and reuse the information that is being transmitted via the sensory channels [Ashcraft, 1998]. In this case, we can see that there are aspects of attention, memory and learning, that support the exploration and navigation of the interface and the components within that interface. In reality, these aspects interrelate and affect each other in more complex ways than we, as yet, understand.

Attention or the locus of attention is simply the place, the site, or the area at which a user is currently focused. This may be in the domain of unconscious or conscious thought, it may be in the auditory domain when listening to speech and conversation, or it may be in the visual domain while studying a painting. However, this single area of attention is the key to understanding how our comprehension is serialised and the effect that interface components and their granularity have when we perceive sensory concepts within a resource; creating a narrative, either consciously or unconsciously.

Cognitive psychologists already understand that the execution of simultaneous tasks is difficult, especially if these are conscious tasks. Repeating tasks at a high-frequency mean that they become automatic, and this automaticity means that they move from a conscious action to an unconscious action. However, the locus of attention for that person is not on the automatic task but the task that is conscious and `running’ in parallel. Despite scattered results suggesting (for example) that, under some circumstances, humans can have two simultaneous loci of spatial attention, the actual measured task performance of human beings on computers suggests that, in the context of interaction, there is one single locus of attention. Therefore, we can understand that for our purposes there is only one single locus of attention, and it is this attention that moves over interactive resources based on the presentation of that resource, the task at hand, and the experience of the user.

While the locus of attention can be applied to conscious and unconscious tasks, it is directed by perception fed from the senses. This is important for interface cognition and the components of the interface under observation. As we shall touch-on later, the locus of attention can be expressed as fixation data from eye tracking work and this locus of attention is serialisable. The main problem with this view is that the locus of attention is specific to the user, the task at hand, as well as the visual resource. In this case, it is difficult to predict how the locus of attention will manifest for every user and every task, and, therefore, the order in which the interface components will be serialised. We can see how the locus of attention is implicitly dealt with by current technologies and techniques and, by comparison to gaze data and fixation times, better understand how the serialisation of visual components can be based on the ‘mean time to fixation’.

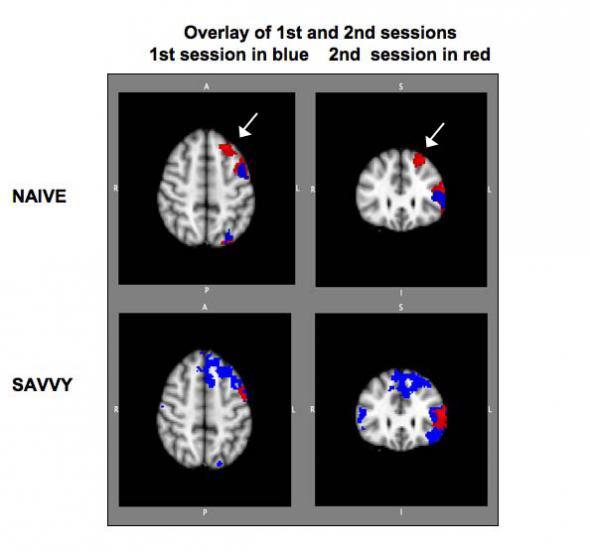

It would be comforting to believe that we had a well-defined understanding of how memory and learning work in practice. While we do have some idea, most of our knowledge regarding memory and learning and how these fit into the general neurology of the brain is currently lacking. This said we do have some understanding of the kinds of aspects of memory and learning that affect human-computer interaction (see Figure: Participants with Minimal Online Experience). In general, sensory memories move via attention into short-term or working memory, the more we revisit the short-term memory, the more we are likely to be able to move this working memory into long-term memory.

In reality, areas of the brain are associated with the sensory inputs: iconic, for visual stimuli; echoic, for auditory stimuli; and haptic for tactile stimuli. However, visual stimuli prove to be the most supported of the senses, from a neurological perspective with over fifty areas of the brain devoted to processing vision, and only one devoted to hearing. In general, then, the UX specialist should understand that we learn and commit to memory by repetition. This repetition may be via rehearsal, it may be via foreknowledge, or it may be via an understanding of something that we have done before, in all cases however repetition is key. Indeed, this repetition is closely linked to the ability to learn and discover an interface, in the first person, as opposed to second hand via the help system. This makes the ability for users to self-explore the interface and interactive aspects of the system, paramount. Many users whom I talk with often state that they explore incrementally and don’t refer much to the manuals. With this in mind, interfaces and systems should be designed to be as familiar as possible, dovetailing into the processes of the specific user as opposed to some generalised concept of the person, and should support aspects of repeatability and familiarity, specifically for this purpose.

Exploration can be thought of like the whole experience of moving from one interface component to another, regardless of whether the destination is known at the start of navigation or if the traversal is initially aimless. Movement and exploration of the interface also involve orientation, interface design, purpose, and mobility. The latter defined as the ability to move freely, easily and confidently around the interface. In this context, a successful exploration, of the interactive elements, is one in which the desired location is easily reached or discovered. Conventionally, exploration can be separated into two aspects: Those of Navigation and Orientation. Orientation can be thought of as knowledge of the basic spatial relationships between components within the interface. It is used as a term to suggest a comprehension of an interactive environment or components that relate to exploration within the environment. How a person is oriented is crucial to successful interaction. Information about position, direction, desired location, and route are all bound up with the concept of orientation. Navigation, in contrast, suggests an ability of movement within the local environment. This navigation can be either by the use of pre-planning using help or previous knowledge or by navigating ‘on-the-fly’ and as such a knowledge of immediate components and barriers are required. Navigation and orientation are key within the UX domain because they enable the user to easily understand, and interact with, the interface. However, in some ways, more importantly, they enable the interface to be learnt by a self-teaching process. Facilitating exploration through the use of an easily navigable interface means that users will intuitively understand the actions that are required of them and that the need for help documentation is reduced.

4.2.3 Explicit and Implicit Communication

Information can be transmitted in a number of different ways, and these ways may be either implicit (covert) or explicit (overt). In this case let us refer to information transmission as communication; in that information is communicated to the user and the user requirements are then communicated back to the computer via the input and control mechanisms. Explicit communication is often well understood and centres on the visual, or auditory, transmission of both text and images (or sounds) for consumption by the user. Implicit communications are, however, a little more difficult to define. In this case, I refer to those aspects of the visual or auditory user experience that are in some ways intangible. By which I mean aspects such as aesthetic or emotional responses [Pelachaud, 2012] to aspects of the communication.

Explicit Communication. Communication and complexity are closely related whereby complexity directly affects the ease of communication between the user and the interface or system. Communication mainly occurs via the visual layout of the interface and the textual labels that must be read by the user to understand the interactive communication with them. People read text by using jerky eye movements (called ‘Saccades’) which then stop and fixate on a keyword for around 250 milliseconds. These fixations vary and last longer for more complex text, and are focussed on forward fixations with regressive (backward) fixations only occurring 10-15 percent of the time when reading becomes more difficult. People, reading at speed by scanning for just appropriate information, tend to fixate less often and for a shorter time. However, they can only remember the gist of the information they have read; and are not able to give a comprehensive discourse on the information encountered (see Figure: Visualising Words). This means that comprehensive descriptions of interfaces for users, when quickly scanning an interactive feature, are not used in the decision-making process of the user. Indeed, cognitive overload is a critical problem when navigating large interactive resources. This overload is increased if the interaction is non-linear and may switch context unexpectedly. Preview through summaries is key to improving the cognition of users within complex interfaces, but complex prompts can also overload the reader with extraneous information.

In addition to the problems of providing too much textual information the complexities of that information must also be assessed. The Flesch/Flesch–Kincaid Readability Tests are designed to indicate comprehension difficulty when reading a passage of contemporary academic English. Invented by Flesch and enhanced by Kincaid, the Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level Test1 analyses and rates text on a U.S. grade–school level based on the average number of syllables per word and words per sentence. For example, a score of 8.0 means that an eighth grader would understand the text. Keeping this in mind, the HCI specialist should try to make the interface labels and prompts as understandable as possible. However this may also mean the use of jargon is acceptable in situations where a specialist tool is required, or when a tool is being developed for a specialist audience.

Implicit Communication. Aesthetics is commonly defined as the appreciation of the beautiful or pleasing, but this terminology is still controversial. Visual aesthetics is ‘the science of how things are known via the senses’ which refers to user perception and cognition. Specifically, the phrase ‘aesthetically pleasing’ interfaces are commonly used to describe interfaces that are perceived by users as clean, clear, organised, beautiful and interesting. These terms are just a sample of the many different terms used to describe aesthetics, which are commonly used in interaction design. Human-computer interaction work mostly emphasises performance criteria, such as time to learn, error rate and time to complete a task, and pays less attention to aesthetics. However, UX work has tried to expand this narrow (‘Reductionist’) view of experience, by trying to understand how aesthetics and emotion can affect a viewer’s perception - but the relationship between the aesthetic presentation of an interface and the user’s interaction is still not well understood.

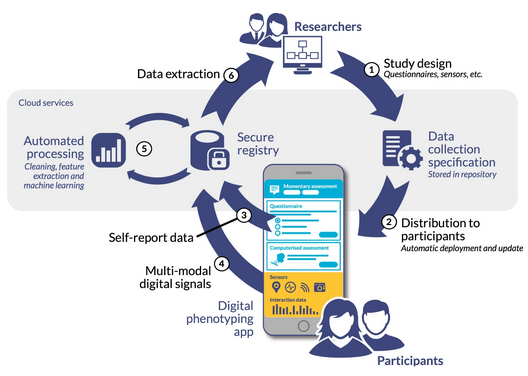

The latest scientific findings indicate that emotions play an essential role in decision making, perception, learning, and more–that is, they influence the very mechanisms of rational thinking. Not only too much, but too little emotion can impair decision making [Picard, 1997]. This is now referred to as ‘Affective Computing’ in which biometric instruments such as Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), Gaze Analysis and Heart Rate Monitoring are used to determine a user’s emotional state via their physiological changes. Further, affective computing also seeks ways to change those states or exhibit control over technology, based upon them2.

4.3 Input and Control

The final piece of the puzzle, when discussing UX, is the ability to enter information for the computer to work with. In general, this is usually accomplished by use of the GUI working in combination with the keyboard and the mouse. However, this is not the entire story, and indeed there are many kinds of entry devices which can be used for information input, selection, and target acquisition [Brand, 1988]. In some cases, specialist devices, such as head operated mice have been used, in others gaze and blink detection, however, in most cases, the mouse and keyboard will be the de-facto combination. However, as a UX engineer you should also be aware of the different types of devices that are available and their relationship to each other. In this way, you will be able to make accurate and suitable choices when specifying non-standard systems.

Text Entry via the keyboard is the predominant means of data input for standard computer systems. These keyboards range from the standard QWERTY keyboard, which is inefficient and encourages fatigue, through the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, ergonomically designed using character frequency, to the Maltron keyboard designed to alleviate carpal tunnel syndrome and repetitive strain injury. There are however other forms of text entry. These range from the T9 keyboard found on most mobile phones and small devices with only nine keys. Through to soft keyboards, found as part of touch screen systems, or as assistive technologies for users with motor impairment, where a physical keyboard cannot be controlled. You may encounter many such methods of text entry, or indeed be required to design some yourself. If the latter is the case, you should make sure that your designs are base on an understanding of the physiological and cognitive systems at work.

The Written Word, cursive script, was seen for a long period as the most natural way of entering text into a computer system; because it relied on the use of a skill already learnt. The main bar to text entry via the written word was that handwriting recognition was computationally intensive and, therefore, underdeveloped. One of the first handwriting recognition systems to gain popularity was that employed by the Apple Newton, which could understand written English characters, however, accuracy was a problem. Alternatives to handwriting recognition arrived in the form of pseudo-handwriting, such as the Graffiti system that was essentially a single stroke shorthand handwriting system. Current increasing computational power and complexity of the algorithms used to understand handwriting have led to a resurgence in its use in the form of systems such as Inkwell. Indeed, with the advent of systems such as the Logitech io2 Digital Writing System, handwriting recognition has become a computer-paper hybrid.

Pointing Devices, for drawing and target acquisition is handled, in most cases, by the ubiquitous mouse. Indeed, this is the most effective way of acquiring a target; with the exclusion of the touch-screen. There are however other systems that may be more suitable in certain environments. These may include the conventional trackpad, the trackball, or the joystick. Indeed, variations on the joystick have been created for mobile devices that behave similarly to their desktop counterparts but have a more limited mobility. Likewise, the trackball also has a miniaturised version present on the Blackberry range of mobile PDAs, but its adoption into widespread mobile use has been limited. Finally, the touch screen is seeing a resurgence in the tablet computing sector where the computational device is conventionally held close enough for easy touch screen activation, either by the operators finger or a stylus.

Haptic Interaction is not widely used beyond the realm of immersive or collaborative environments. In order to interact haptically with a virtual world, the user holds the ‘end-effector’ of the device. Currently, haptic devices support only point contact, so touching a virtual object with the end-effector is like touching it using a pen or stick. As the user moves the end-effector around, its co-ordinates are sent to the virtual environment simulator (for example see Figure: Phantom Desktop Haptic Device). If the end-effector collides with a haptically-enabled object, the device will render forces to simulate the object’s surface. Impedance control means that a force is applied only when required: if the end-effector penetrates the surface of an object, for example, forces will be generated to push the end-effector out, to create the impression that it is touching the surface of the object. In admittance control, the displacement of the end-effector is calculated according to the virtual medium through which it is moving, and the forces exerted on it by the user. Moving through air requires a very high control gain from force input to displacement output, whereas touching a hard surface requires a very low control gain. Admittance control requires far more intensive processing than impedance control but makes it much easier to simulate surfaces with low friction, or objects with mass.

Speech Input is increasing in popularity due to its ability to handle naturally spoken phrases with an acceptable level of accuracy. There are however only a very few speech recognition engines that have gained enough maturity to be effectively used. The most popular of these is the Dragon speech engine, used in Dragon NaturallySpeaking and Mac Dictate software applications. Speech input can be very effective when used in constrained environments or devices, or when other forms of input are slow or inappropriate. For instance text input by an unskilled typist can be time-consuming whereas general dictation can be reasonably fast; and with the introduction of applicators such as Apple’s ‘SIRI’, is become increasingly widespread.

Touch Interfaces have become more prevalent in recent times. These interfaces originally began with single touch graphic pads (such as those built commercially by Wacom) as well as standard touch-screens that removed the need for a conventional pointing device. The touch interface has become progressively more accepted especially for handheld and mobile devices where the distance from the user to the screen is much smaller than for desktop systems. Further, touch-pads that mimic a standard pointing device, but within a smaller footprint, became commonplace in laptop computer systems; but up until the late 2008’s all these systems were only substitutes for a standard mouse pointing device. The real advance came with the introduction of gestural touch and multi-touch systems that enabled the control of mobile devices to become much more intuitive/familiar; with the use of swipes and stretches of the document or application within the viewport. These multi-touch gestural systems have now become standard in most smartphones and tablet computing devices, and their use normalised by providing easy APIs within operating systems; such as iOS. These gestural touch systems are markedly different from gesture recognition whereby a device is moved within a three-dimensional space. In reality, touchscreen gestures are about the two-dimensional movement of the user’s fingers, whereas gesture recognition is about the position and orientation of a device within three-dimensional space (often using accelerometers, optical sensing, gyroscopic systems, and/or Hall effect cells).

Gesture Recognition was originally seen as an area mostly for research and academic investigation. However, two products have changed this view in recent times. The first of these is the popular games console, the Nintendo Wii, which uses a game controller as a handheld pointing device and detects movement in three dimensions. This movement detection enables the system to understand certain gestures, thereby making game-play more interactive and intuitive. Because it can recognise naturalistic, familiar, real world gestures and motions it has become popular with people who would not normally consider themselves to be games console users. The second major commercial success of gesture recognition is the Apple iOS. The iOS3 can also detect movement in three-dimensions and uses similar recognition as the Nintendo games console to interact with the user. The main difference is that the iOS uses gesture and movement recognition to more effectively support general computational and communication-based tasks.

There are a number of specialist input devices that have not gained general popularity but nevertheless may enable the UX specialist to overcome problems not solvable using other input devices. These include such technologies as the Head Operated Mouse (see Figure: Head Operated Mouse), which enables users without full body movement to control a screen pointer, and can be coupled with blink detection to enable target acquisition. Simple binary switches are also used for selecting text entry from scanning soft keypads using deliberate key-presses or, in the case of systems such as the Hands-free Mouse COntrol System (HaMCoS), via the monitoring of any muscle contraction. Gaze detection is also popular in some cases, certainly concerning in-flight control of military aircraft. Indeed, force feedback has also been used as part of military control systems but has taken on a wider use when some haptic awareness is required; such as remote surgical procedures. In this case, force feedback mice and force feedback joysticks have been utilised to make the remote sensory experience more real to the user. Light pens have given rise to pen-computing but have now themselves become less used especially with the advent of the touch-screen. Finally, immersive systems, or parts of those immersive systems, have enjoyed some limited popularity. These systems originally included body suits, immersive helmets, and gloves. However, the most popular aspect used singularly has been the interactive glove, which provides tactile feedback coupled with pointing and target acquisition.

4.4 Summary

Understanding how we use our senses: seeing (visual channel), hearing (auditory channel), smelling (olfactory channel), and touching (haptic channel) enables us to understand how to communicate information regarding the state of the system via the interface. Knowledge of the natural processes of the mind: attention, memory and learning, exploration and navigation, affective communication and complexity, and aesthetics, enables an understanding of how the information we transmit can better fit the users mental processes. Finally, understanding how input and control are enacted can enable us to choose from the many kinds of entry devices which can be used for information input, selection, and for target acquisition. However, we must remember that there are many different kinds of people, and these people have many different types of sensory or physical requirements which must be taken into account at all stages of the construction process.

4.4.1 Optional Further Reading / Resources

- [M. H. Ashcraft.] Fundamentals of cognition. Longman, New York, 1998.

- [S. Brand.] The Media Lab: inventing the future at MIT. Penguin Books, New York, N.Y., U.S.A., 1988.

- [A. Huberman] Andrew Huberman. YouTube. (2013, April 21). Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC2D2CMWXMOVWx7giW1n3LIg

- [C. Pelachaud.] Emotion-oriented systems. ISTE, London, 2012.

- [R. W. Picard.] Affective computing. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1997.

- [J. Raskin.] The humane interface: new directions for designing interactive systems. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 2000.

- [S. Weinschenk.] 100 things every designer needs to know about people. Voices that matter. New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2011.

5. Practical Ethics

A man without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world.

– Albert Camus

The primary purpose of evaluations involving human subjects is to improve our knowledge and understanding of the human environment including medical, clinical, social, and technological aspects. Even the best proven examples, theories, principles, and statements of relationships must continuously be challenged through evaluation for their effectiveness, efficiency, affectiveness, engagement and quality. In current evaluation and experimental practice some procedures, will by nature, involve a number of risks and burdens. UX specialists should be aware of the ethical, legal and regulatory requirements for evaluation on human subjects in their own countries as well as applicable international requirements. No national ethical, legal or regulatory requirement should be allowed to reduce or eliminate any of the protections for human participants which you as a professional UX practitioner are bound to follow, as part of your personal code of conduct.

Evaluation in the human science, of which UX is one example, is subject to ethical standards that promote respect for all human beings and protect their health and rights. Some evaluation populations are vulnerable and need special protection. The particular needs of the economically and medically disadvantaged must be recognised. Special attention is also required for those who cannot give, or refuse, consent for themselves, for those who may be subject to giving consent under duress, for those who will not benefit personally from the evaluation, and for those for whom the evaluation is combined with care.

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and torturing people under the guise of research.

However, the question for many UX specialists is, why do these standards, codes of conduct or practice, and duties of care exist. What is their point, why were they formulated, and what is the intended effect of their use?

5.1 The Need for Ethical Approaches

Rigourously structured hierarchical societies, as were common up until the 1960s, and indeed some may say are still common today, are often not noted for their inclusion or respect for all citizens. Indeed, one sided power dynamics have been rife in most societies. This power differential led to increasing abuse of those with less power by those with more power. This was no different within the scientific, medical, or empirical communities. Indeed, as the main proponents of scientific evaluation were, in most cases, economically established, educated, and therefore from the upper levels of society, abuses of human ‘subjects’4 became rife. Even when this abuse was conducted by proxy and there was no direct intervention of the scientist in the evaluation.

Indeed, these kinds of societies are often driven by persons who are in a position of power (at the upper levels) imposing their will on communities of people (at the lower levels). Further, these levels are often defined by both economic structure or some kind of inherited status or honour, which often means that citizens at the upper level have no concept of what it is to be a member of one of the lower levels. While it would be comforting to think that this only occurred in old European societies it would be ridiculous to suggest that this kind of stratified society did not occur in just about every civilisation, even if their formulation was based on a very specific and unique set of societal values.

In most cases, academic achievement provided a route into the upper levels of society, but also limited entry into those levels; as education was not widely available to an economically deprived population characteristic of the lower levels. In this case, societies worked by having a large population employed in menial tasks, moving to unskilled labour, to more skilled labour, through craftsmanship and professional levels, into the gentry, aristocracy, and higher levels of the demographic. In most cases, the lack of a meritocracy, and the absence of any understanding of the ethical principles at work, meant that the upper levels of society often regard the lower levels as a resource to be used.

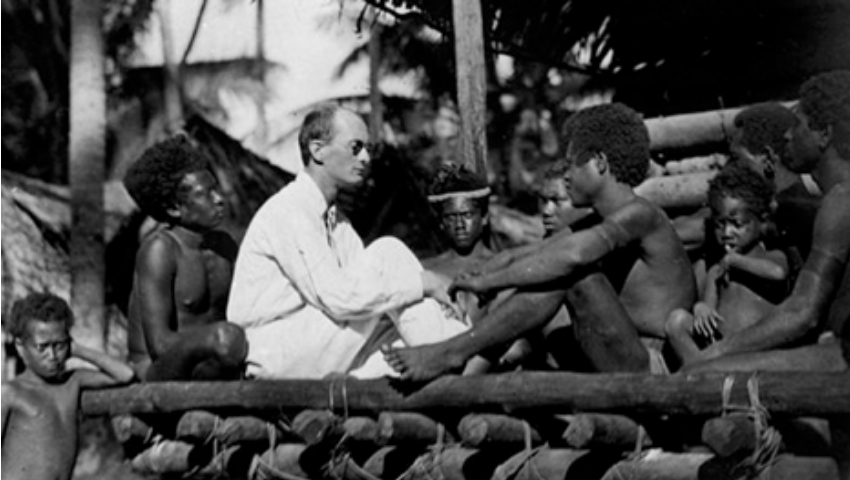

Many cases of abuse have been recorded in experimentation and investigations from the late 17th and early 18th centuries onwards. These abuses took place under the guise of furthering our knowledge of humankind and were often perpetrated against dominated populations. There are many recorded abuses of Australian aboriginal peoples, African peoples, and indigenous south American peoples, in the name of the advancement of our understanding of the world and the peoples within it. These abuses were not purely limited to the European colonies, but also occurred within the lower classes of European society; in some cases involving the murder (see Burke and Hare) and sale of subjects to complicit surgeons for anatomical investigation. Experimenters contented themselves with the rationale of John Stuart Mill, which suggests that experimental evaluation should do more good than harm, or that more people should benefit than suffer. However, there was no concept of justice in this initial rationale as the people who usually ended up suffering were the underprivileged and those who benefited were often the privileged minority.

The ethical rules that grew up in the late 1950s and 60s came about due to the widespread abuse of human subjects in 1940s Germany:

Once these abuses came to light, including the inhumane treatment meted out to adults and children alike, organisations such as the American Psychological Association and the American Medical Association began to examine their own evaluation practices. This investigation did not prove to be a pleasant experience, and while there were no abuses on the scale of the German Human Experiments it was found that subjects were still being badly treated even as late as the 1960s.

This growing criticism led to the need for ethical policies which would enable evaluation to be undertaken (there is clearly a benefit to society in scientific, medical, and clinical evaluation) but with a certain set of principles which ensured the well-being of the subjects. Obviously, a comprehensive ethical structure, to include all possible cases, is difficult to formulate at the first attempt. It is for this reason that there have been continual iterative revisions to many evaluation ethics guidelines. However, revisions have slowed and the key principles that have now become firm, should enable the UX specialist to design ethical studies taking into account the inherent human rights of all who participate in them.

5.2 Subjects or Participants?

You may be wondering why this overview matters to you as an UX specialist. In reality, ethics is a form of ‘right thinking’ which encourages us to moderate our implicit power over the people, and concepts, we wish to understand or investigate. You’ll notice that in all but the most recent ethical evaluation standards the term ‘subject’ is used to denote the human taking part in the experimental investigation. Indeed, I have deliberately used the term subject in all of my discussions up to this point, to make a very implicit way of thinking, explicit. The Oxford English Dictionary5 (OED) defines the term ‘subject’ variously as:

Of course the OED also describes a subject in a less pejorative manner as a person towards whom or which action, thought, or feeling is directed, or a person upon whom an experiment is made. Yet they also define the term ‘participant’, again variously, as:

Even taking the most neutral meaning of the term subject (in the context of human experimentation), and comparing it with that of the participant, a subject has an experiment made upon them, where as a participant shares in the experimental process. These definitions make it obvious that, even until quite recently, specialists considered the people partaking in their evaluation to be subjects of either the scientist or the experimentation. In reality, most specialists now use of the term participant to enable them to understand that, one-time subjects, are freely and informatively participating in their evaluation and should not be subjugated by that evaluation or the specialists undertaking it. Indeed, as we have seen in ‘evaluation methodologies’ (see Ethics), the more a human participant feels like a subject, the more they tend to agree with the evaluator. This means that bias is introduced into the experimental framework.

So then, by understanding that we have either evaluation participants, or respondents (a term often used, within sociology and the social sciences, to denote people participating in quantitative survey methods), we implicitly convey a level of respect and, in some ways, gratitude for the participation of the users. Understanding this key factor enables us to make better decisions with regard to participant recruitment and selection, assignment and control, and the definition and measurement of the variables. By understanding the worth of our participants we can emphasise the humane and sensitive treatment of our users who are often put at varying degrees of risk or threat during the experiment procedure. Obviously, within the UX domain these risks and threats are usually minimal or non-existent but by understanding that they may occur, and that a risk assessment is required, we are better able to see our participants as equals, as opposed to dominated subjects.

5.3 Keeping Us Honest

Good ethics makes good science and bad ethics makes bad science because the ethical process keeps us honest with regard to the kind of methodologies we are using and the kind of analysis that will be applied.

Ethics is not just about the participant but it is also about the outcomes of the evaluation being performed. Understanding the correct and appropriate methodology and having that methodology doubled checked by a evaluation ethics committee enables the UX practitioner to better account for all aspects of the evaluation design. As well as including that of the analysis it also encourages the understanding of how the data will be used and stored. As we have seen (see ‘Bedrock’), good science is based on the principle that any assertion made must have the possibility of being falsified (or refuted). This does not mean that the assertion is false, but just that it is possible to refute the statement. This refutability is an important concept in science, indeed, the term `testability’ is related, and means that an assertion can be falsified through experimentation alone. However, this possibility of testability can only occur if the collected data is available and the method is explicit enough to be understandable by a third party. Therefore, presenting your work to an ethics committee enables you to gain an understanding of the aspects of the methodology which are not repeatable without your presence. In addition, it also enables you to identify any weaknesses within the methodology or aspects, which are not covered within the write-up, but which are implicitly understood by yourself or the team conducting the evaluation.

In addition, ethical approval can help us in demonstrating to other scientists or UX specialists, that our methods for data gathering and analysis are well found. Indeed, presentation to an ethical committee is in some ways similar to the peer review process, in that any inadequacies within the methodology can be found before the experimental work commences, or sources of funding are approached. Indeed, the more ethical applications undertaken, the more likely it is that the methodological aspects of the work will become second nature and the evaluation design will in turn become easier.

It is therefore, very difficult to create a evaluation methodology which is inconsistent with the aims of the evaluation or inappropriate with regard to the human participants; and still have it pass the ethical vetting as applied by a standard ethics committee. Indeed, many ethical committees require that a technical report is submitted after the ethical procedures are undertaken so that an analysis of how the methodology was applied in real-life can be understood; and if there are any possible adverse consequences from this application. These kinds of technical reports often require data analysis and deviations from the agreed methodology to be accounted for. If not there may be legal consequences, or at the very least, problems with regard to the obligatory insurance of ethically approved procedures; for both the specific work and for future applications.

5.4 Practical Ethical Procedures

Before commencing any discussion regarding ethics and the human participant it may be useful to understand exactly what we mean by ethics. Here we understand that ethics relates to morals; a term used to describe the behaviour or aspects of the human character that is either good or bad, right or wrong, good or evil. Ethics then is a formulated way of understanding and applying the characteristics and traits that are either good or bad; in reality, the moral principles by which people are guided. In the case of human-computer interaction, ethics is the rules of conduct, recognised by certain organisations, which can be applied to aspects of UX evaluation. In the wider sense ethics and morals are sub-domains of civil, political, or international law [Sales and Folkman, 2000].

Ethical procedures then are often seen as a superfluous waste of time, or at best an activity in form filling, by most UX specialists. The ethical procedures that are required seem to be obtuse and unwieldy especially when there is little likelihood of danger, or negative outcomes, for the participants. The most practitioners reason that this is not, after all, a medical study or a clinical trial, there will be no invasive procedures or possibility of harm coming to a participant, so why do we need to undergo an ethical control?

This is entirely true for most cases within the user experience domain. However, the ethical process is a critical component of good evaluation design because it encourages the UX specialist to focus on the methodology and the analysis techniques to be used within that methodology. It is not the aim of the organisational ethical body to place unreasonable constraints on the UXer, but more properly, to make sure that the study designers possess a good understanding of what methodological procedures will be carried out, how they will be analysed, and how these two aspects may impact the human participants.

Ethics are critical component of good evaluation design because it encourages the UX specialist to focus on the methodology and the analysis techniques to be used within that methodology.

In reality then, ethical applications are focussed on ensuring due diligence, a form of standard of care relating to the degree of prudence and caution required of an individual who is under a duty of care. To breach this standard may end in a successful action for negligence, however, in some cases it may be that ethical approval is not required at all:

“Interventions that are designed solely to enhance the well-being of an individual patient or client and that have a reasonable expectation of success. The purpose of medical or behavioural practice is to provide diagnosis, preventative treatment, or therapy to particular individuals. By contrast, the term research designates and activities designed to develop or contribute generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships).”

In the case of UX then, the ethical procedure is far more about good evaluation methodology than it is about ticking procedural boxes.

As you already know, UX is an interdisciplinary subject and a relatively new one at that. This means that there are no ethical guidelines specifically to address the user experience domain. In this case, ethical principles and the ethical lead is taken from related disciplines such as psychology, medicine, and biomedical research. This means that, from the perspective of the UX specialist, the ethical aspects of the evaluation can sometimes seem like an incoherent ‘rule soup’.

To try and clarify the UX ethical situation I’ll be using principles guidelines and best practice taken from a range of sources, including:

- The American Psychological Association’s (APA), ‘Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct’;

- The United States Public Health Service Act (Title 45, Part 46, Appendix B), ‘Protection of Human Subjects’;

- The Belmont Report, ‘Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research’;

- The Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences, ‘International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies’; and finally

- The World Medical Association’s, ‘Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects’.

5.5 Potted Principles of Practical Ethical Procedures

As a responsible UX’er, you are required to conduct your evaluations following the highest scientific and ethical standards [Association, 2003]. In particular, you must protect the rights, interests and dignity of the human participants of the evaluation, and your fellow researchers themselves, from harm. The role of your Ethics body or committee is to ensure that any relevant experimentation or testing meets these high ethical standards, by seeking all information appropriate for ethical assessment, interviewing you as an applicant where possible, and coming to a judgement as to whether the proposed work should be: given ethical approval, refused ethical approval, or given approval subject specified conditions.

5.5.1 In brief…

We can see that the following list of key principles should be taken into account in any evaluation design be it in the field or within the user laboratory.

- Competence Keep up to date, know your limitations, ask for advice;

- Integrity Have no axe to grind or desired outcome;

- Science Follow the Scientific Method;

- Respect Assess your participant’s autonomy and capability of self-determination, treat participants as equals, ensure their welfare;

- Benefits Maximising benefits and minimising possible harms according to your best judgement, seek advice from your organisations ethics committee;

- Justice Research should be undertaken with participants who will benefit from the results of that research;

- Trust Maintain trust, anonymity, confidentiality and privacy, ensure participants fully understand their roles and responsibilities and those of the experimenter; and finally

- Responsibility You have a duty of care, not only to your participants, but also to the community from which they are drawn, and your community of practice.

Some practical considerations must be undergone when an application for ethical approval is being created. The questions are often similar over most ethical applications which involve UX. When creating any ethical procedure, you need to ask yourself some leading ethical questions to understand the various requirements of the ethical application. In some cases understanding these questions before you write your methodology is preferable, in this way you cannot be led down unethically valid path by understanding what changes you need to make to your evaluation work while you are designing it, and before it becomes too difficult to revise. Here I arrange aspects of the ethical procedure by ethical principles. These aspects describe the kinds of issues which should be considered when creating a methodology and cover the project: overview, participants, risks, safeguards, data protection and confidentiality, reporting arrangements, funding and sponsorship, and finally, conflicts of interest.

5.5.2 You Must Be Competent

- Other Staff: Assess, and suitable train, the other staff involved; and

- Fellow Researchers: Assess the potential for adverse effects, risks or hazards, pain, discomfort, distress, or inconvenience to the researchers themselves.

5.5.3 You Must Have Integrity

- Previous Participation: Will any research participants be recruited who are involved in existing evaluations or have recently been involved in any evaluation before recruitment? Assess the steps you will take to find out;

- Reimbursement: Will individual evaluation participants receive reimbursement of expenses or any other incentives or benefits for taking part in this evaluation? Assess if the UXers may change their attitudes towards participants, knowing this;

- Conflict of interest; Will individual evaluators receive any personal payment over and above normal salary and reimbursement of expenses for undertaking this evaluation? Further, will the host organisation or the researcher’s department(s) or institution(s) receive any payment of benefits more than the costs of undertaking the research? Assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest;

- Personal Involvement: Does the Chief UX Specialist or any other UXer/collaborator have any direct personal involvement (e.g. financial, share-holding, personal relationship, etc.) in the organisation sponsoring or funding the evaluation that may give rise to a possible conflict of interest? Again, assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest; and

- Funding and Sponsorship: Has external funding for the evaluation been secured? Has the external funder of the evaluation agreed to act as a sponsor, as set out in any evaluation governance frameworks? Has the employer of the Chief UX Specialist agreed to act as sponsor of the evaluation? Again, assess the possibility of these factors creating a conflict of interest.

5.5.4 Conform to Scientific Principles

- Objective: What is the principal evaluation question/objective? Understanding this objective enables the evaluation to be focused;

- Justification: What is the scientific justification for the evaluation? Give a background to assess if any similar evaluations have been done, and state why this is an area of importance;

- Assessment: How has the scientific quality of the evaluation been assessed? This could include independent external review; review within a company; review within a multi-centre research group; internal review (e.g. involving colleagues, academic supervisor); none external to the investigator; other, e.g. methodological guidelines;

- Demographics: Assess the total number of participants required along with their, sex, and the target age range. These should all be indicative of the target evaluation population;

- Purpose: State the design and methodology of the planned evaluation, including a brief explanation of the theoretical framework that informs it. It should be clear exactly what will happen to the evaluation participant, how many times and in what order. Assess any involvement of evaluation participants or communities in the design of the evaluation;

- Duration: Describe the expected total duration of participation in the study for each participant;

- Analysis: Describe the methods of analysis. These may be by statistical, in which case specify the specific statistical experimental design and justify why it was chosen, or using other appropriate methods by which the data will be evaluated to meet the study objectives;

- Independent Review: Has the protocol submitted with this application been the subject of review by an independent evaluator, or UX team? This may not be appropriate but it is advisable if you are worried about any aspects; and

- Dissemination: How is it intended the results of the study will be reported and disseminated? Internal report; Board presentation; written feedback to research participants; presentation to participants or relevant community groups; or by other means.

5.5.5 Respect Your Participants

- Issues: What do you consider to be the main ethical issues that may arise with the proposed study and what steps will be taken to address these? Will any intervention or procedure, which would normally be considered a part of routine care, be withheld from the evaluation participants. Also, consider where the evaluation will take place to ensure privacy and safety;

- Termination: Assess the criteria and process for electively stopping the trial or other evaluations prematurely;

- Consent: Will informed consent be obtained from the evaluation participants? Create procedures to define who will take consent and how it will be done. Give details of how the signed record of consent will be obtained and list your experience in taking consent and of any particular steps to provide information (in addition to a written information sheet) e.g. videos, interactive material. If participants are to be recruited from any of the potentially vulnerable groups, assess the extra steps that will be taken to assure their protection. Consider any arrangements to be made for obtaining consent from a legal representative. If consent is not to be obtained, think about why this is not the case;

- Decision: How long will the participant have to decide whether to take part in the evaluation? You should allow an adequate time;

- Understanding: Implement arrangements for participants who might not adequately understand verbal explanations or written information given in English, or who have special communication needs (e.g. translation, use of interpreters, etc.);

- Activities: Quantify any samples or measurements to be taken. Include any questionnaires, psychological tests, etc. Assess the experience of those administering the procedures and list the activities to be undertaken by participants and the likely duration of each; and

- Distress: Minimise, the need for individual or group interviews/questionnaires to discuss any topics or issues that might be sensitive, embarrassing or upsetting; is it possible that criminal or other disclosures requiring action could take place during the study (e.g. during interviews/group discussions).

5.5.6 Maximise Benefits

- Participants: How many participants will be recruited? If there is more than one group, state how many participants will be recruited in each group. For international studies, say how many participants will be recruited in the UK and total. How was the number of participants decided upon? If a formal sample size calculation was used, indicate how this was done, giving sufficient information to justify and reproduce the calculation;

- Duration: Describe the expected total duration of participation in the study for each participant;

- Vulnerable Groups: Justify their inclusion and consider how you will minimise the risks to groups such as: children under 16; adults with learning difficulties; adults who are unconscious or very severely ill; adults who have a terminal illness; adults in emergency situations; adults with mental illness (particularly if detained under mental health legislation); adults with dementia; prisoners; young offenders; adults in Scotland who are unable to consent for themselves; those who could be considered to have a particularly dependent relationship with the investigator, e.g. those in care homes, students; or other vulnerable groups;

- Benefit: Discuss the potential benefit to evaluation participants;

- Harm: Assess the potential adverse effects, risks or hazards for evaluation participants, including potential for pain, discomfort, distress, inconvenience or changes to lifestyle for research participants;

- Distress: Minimise, the need for individual or group interviews/questionnaires to discuss any topics or issues that might be sensitive, embarrassing or upsetting; is it possible that criminal or other disclosures requiring action could take place during the study (e.g. during interviews/group discussions).

- Termination: Assess the criteria and process for electively stopping the trial or other evaluation prematurely;

- Precautions: Consider the precautions that have been taken to minimise or mitigate any risks;

- Reporting: instigate procedures to facilitate the reporting of adverse events to the organisational authorities; and

- Compensation: What arrangements have been made to provide indemnity and compensation in the event of a claim by, or on behalf of, participants for negligent harm and non-negligent harm;

5.5.7 Ensure Justice

- Demographics: Assess the total number of participants required along with their, sex, and the target age range. These should all be indicative of the population the evaluation will benefit;

- Inclusion: Justify the principal inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- Recruitment: How will potential participants in the study be (i) identified, (ii) approached and (iii) recruited;

- Benefits: Discuss the potential benefit to evaluation participants;

- Reimbursement: Assess whether individual evaluation participants will receive reimbursement of expenses or any other incentives or benefits for taking part in this evaluation; and

- Feedback: Consider making the results of evaluation available to the evaluation participants and the communities from which they are drawn.

5.5.8 Maintain Trust

- Monitoring: Assess arrangements for monitoring and auditing the conduct of the evaluation (will a data monitoring committee be convened?);

- Confidentiality: What measures have been put in place to ensure confidentiality of personal data? Will encryption or other anonymising procedures be used and at what stage? Carefully consider the implications involving any of the following activities (including identification of potential research participants): examination of medical records by those outside the medical facility, such as UX specialists working in bio-informatics or pharmacology; electronic transfer by magnetic or optical media, e-mail or computer networks; sharing of data with other organisations; export of data outside the European Union; use of personal addresses, postcodes, faxes, e-mails or telephone numbers; publication of direct quotations from respondents; publication of data that might allow identification of individuals; use of audio/visual recording devices; storage of personal data as manual files including, home or other personal computers, university computers, private company computers, laptop computers

- Access: Designate someone to have control of and act as the custodian for the data generated by the study and define who will have access to the data generated by the study.

- Analysis: Where will the analysis of the data from the study take place and by whom will it be undertaken?

- Storage: How long will the data from the study be stored, and where will this storage be; and

- Disclosure: Create arrangements to ensure participants receive any information that becomes available during the research that may be relevant to their continued participation.

5.5.9 Social Responsibility

- Monitoring: Assess arrangements for monitoring and auditing the conduct of the evaluation (will a data monitoring committee be convened?);

- Due Diligence: Investigate if a similar application been previously considered by an Ethics Committee in the UK, the European Union or the European Economic Area?

- Disclosure: State if a similar application been previously considered by an Ethics Committee in the UK, the European Union or the European Economic Area. What was the result of the application, how does this one differ and state why you are (re)submitting it;

- Feedback: Consider making the results of evaluation available to the evaluation participants and the communities from which they are drawn.

5.6 Summary

Remember, Ethical applications are focussed on ensuring due diligence. Simply this is a standard of care relating to the degree of prudence and caution required of UX specialist who is under a duty-of-care. As a responsible UX’er, you are required to conduct your evaluation by the highest ethical standards. In particular, you must protect the rights, interests and dignity of the human participants of the evaluation, and your fellow UX’ers, from harm.

To help you accomplish this duty-of-care, you should ask yourself the following questions at all stages of your evaluation design and experimentation: (1) Is the proposed evaluation sufficiently well designed to be of informational value? (2) Does the evaluation pose any risk to participants by such means as the use of deception, of taking sensitive or personal information or using participants who cannot readily give consent? (3) If the risks are placed on participants, does the evaluation adequately control those risks by including procedures for debriefing or the removal or reduction of harm, guaranteeing through the procedures that all information will be obtained anonymously or if that is not possible, guaranteeing that it will remain confidential and providing special safeguards for participants who cannot readily give consent? (4) Have you included a provision for obtaining informed consent from every participant or, if participants cannot give it, from responsible people acting for the benefit of the participant? Will sufficient information be provided to potential participants so that they will be able to give their informed consent? Is there a clear agreement in writing between the evaluation and potential participants? The informed consent should also make it clear that the participant is free to withdraw from an experiment at any time. (5) Have you included adequate feedback information, and debriefing if deception was included, to be given to the participants at the completion of the evaluation? (6) Do you accept full responsibility for safety? (7) Has the proposal been reviewed and approved by the appropriate review board? As we can see these checks cover the range of the principles informing the most practical aspects of human participation in ethically created evaluation projects. By applying them, you will be thinking more holistically about the ethical processes at work within your evaluations, especially if you quickly re-scan them at every stage of the evaluation design. Finally, this is just an abbreviated discussion of ethics; there are plenty more aspects to consider, and some of the most salient points are expanded upon in the Appendix.

5.6.1 Optional Further Reading

- [Barry G. Blundell]. Ethics in Computing, Science, and Engineering: A Student’s Guide to Doing Things Right. N.p.: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- [Nina Brown], Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González. Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology 2nd edition 2020

- [Rebecca Dresser]. Silent Partners: Human Subjects and Research Ethics. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- [Joseph Migga Kizza]. Ethics in Computing: A Concise Module. Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- [Bronislaw Malinowski]. Argonauts of the Western Pacific (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1922), 290.

- [Perry Morrison] and Tom Forester. Computer Ethics: Cautionary Tales and Ethical Dilemmas in Computing. United Kingdom: MIT Press, 1994.

- [David B. Resnik]. The Ethics of Research with Human Subjects: Protecting People, Advancing Science, Promoting Trust. Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- [B. D. Sales] and S. Folkman. Ethics in research with human participants. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., 2000.

5.6.2 International Standards

- [APA] Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychological Association, 2003.

- [BELMONT] The Belmont Report, ‘Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research’.

- [CIOMS] The Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences, ‘International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies’.

- [HS-ACT] The United States Public Health Service Act (Title 45, Part 46, Appendix B), ‘Protection of Human Subjects’.