9. Prototyping and Rapid Application Development

“If a picture is worth 1000 words, a prototype is worth 1000 meetings.”

– David & Tom Kelley, Founder, and Partner of renowned Design and Innovation Consultancy IDEO

In this chapter we’re going to be looking at Rapid Application Development (RAD) and Prototyping. By prototyping we simply mean a mock up that can (often) be run. And when we say run we mean this could be a wizard-of-oz kind of run, in that sense, whereby there’s a person behind the screen making it work. Alternatively, it could be actually running to a certain level of accuracy which could be implemented in part and parts that might not be implemented. So it just depends, but run means that things can be looked at by users. And you can work through the steps of how things might work.

In this case, the initial investment is low in terms of time and coding, because it’s really a prototype, it’s not the real thing and so hasn’t taken the development effort required to make everything work. Its job it to just allow the user to get closer to what the system could look like and how it could work without making a high initial investment, and as such it is cheaper in the initial development but also allows a user to make rapid changes over time.

9.1 Prototyping

UX prototyping refers to the process of creating interactive and tangible representations of user experiences. It involves building low-fidelity or high-fidelity prototypes that simulate the functionality, flow, and visual design of a digital product or service. UX prototyping plays a crucial role in the user-centred design process, allowing designers and stakeholders to gather feedback, test concepts, and iterate on designs before the actual development phase.

Key aspects of UX prototyping focus on:

User-Centric Approach: UX prototyping focuses on understanding and addressing user needs and expectations. By creating prototypes, designers can gather user feedback early in the design process and make informed decisions based on user insights.

Interactive Simulations: Prototypes are designed to simulate user interactions and workflows, providing a realistic representation of how the final product will behave. This allows designers to test and refine the user experience before investing in development.

Low-Fidelity Prototypes: Low-fidelity prototypes are quick and simple representations of design concepts, often created using paper sketches or digital wireframes. They are useful for exploring and validating initial ideas, gathering feedback, and making early design decisions.

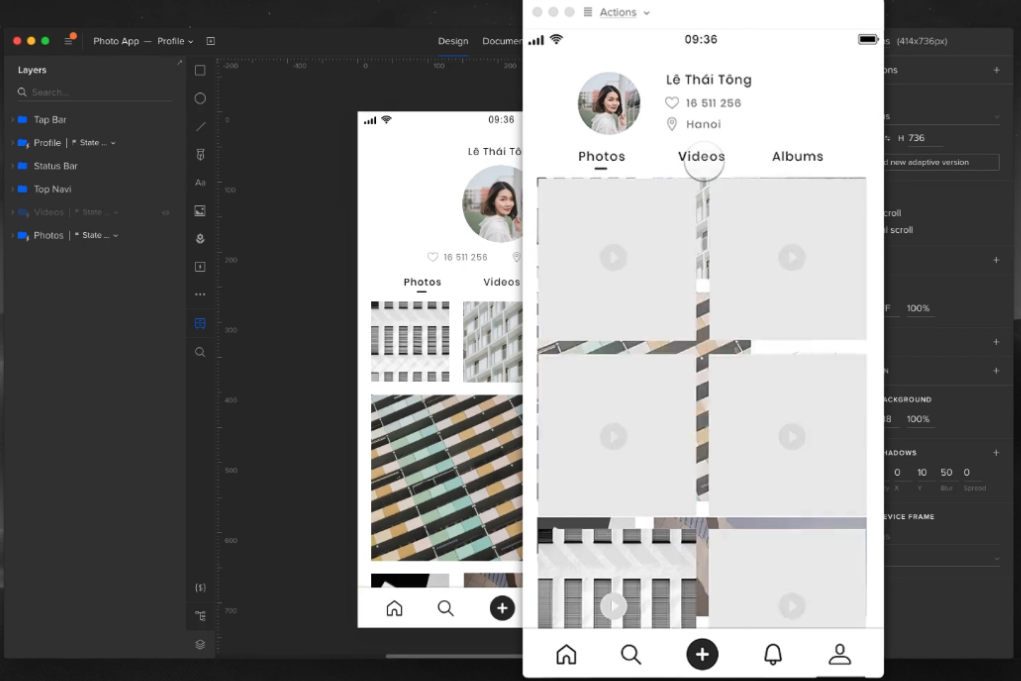

High-Fidelity Prototypes: High-fidelity prototypes are more detailed and visually polished, closely resembling the final product. They can be interactive, allowing users to navigate through screens, interact with elements, and experience the product’s functionality. High-fidelity prototypes are valuable for user testing, stakeholder presentations, and demonstrating the user experience to clients.

Iterative Design Process: UX prototyping facilitates an iterative design process, enabling designers to make improvements based on user feedback. By testing and refining prototypes, designers can uncover usability issues, identify areas for improvement, and iterate on the design until it meets user and business goals.

Collaboration and Communication: Prototypes serve as a visual and interactive communication tool, enabling designers to effectively communicate their ideas to stakeholders, developers, and other team members. Prototypes bridge the gap between design and development teams, aligning everyone on the project’s vision and goals.

Prototyping Tools: Various prototyping tools are available that aid in creating interactive prototypes, such as Sketch, Adobe XD, Figma, InVision, and Axure RP. These tools offer features like drag-and-drop interfaces, interactions, animations, and the ability to simulate user flows.

Overall, UX prototyping is a powerful technique that empowers designers to iterate, test, and refine their designs based on user feedback. By incorporating prototyping into the design process, teams can create more user-centred and effective digital products and services. We will be focusing on the fidelity spectrum which runs from lo-fidelity at one end, and hi-fidelity at the other.

9.2 The Fidelity Spectrum

What you’ll find is that there are two extremes of prototypes; lo fidelity prototyping and hi fidelity prototyping. And as we move from lo fidelity to hi fidelity there is really a spectrum, and a diversity of change such that lo-fi facilitates big changes which become increasingly small as you move through to hi-fi. This is because there’s more work and more cost involved in the hi-fi. Also, as we’ve seen the closer you get to hi fidelity prototypes, the less likely it is a user will want to make changes because they’ll feel you’ve already put a lot of work into it. So really make sure that the users have been involved on the lo-fidelity prototypes, just so that you can understand any final changes or issues that need to be fixed from a user perspective, realising you are not going to get these to the level of large changes the closer you get to hi-fi prototyping.

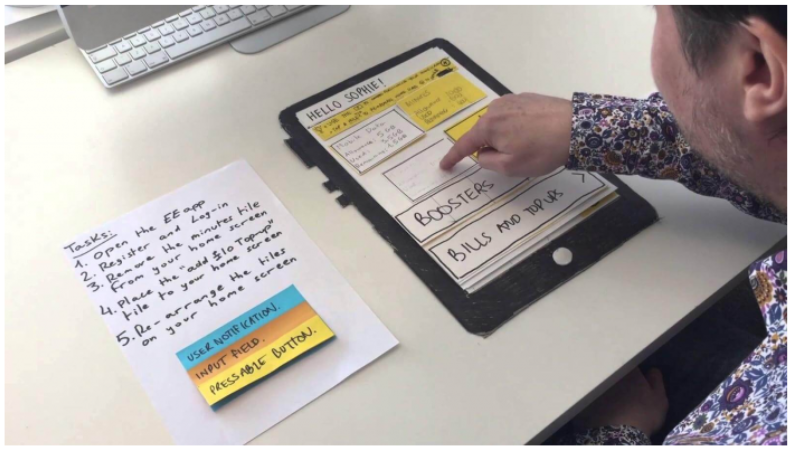

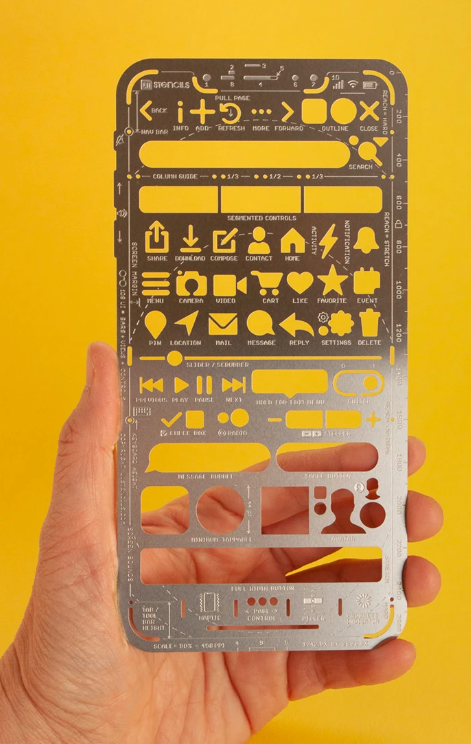

Along the spectrum you can increasingly refine the lo-fi prototypes moving from hand drawn prototypes to templates that are still lo-fi but look much more professional, giving a more exact representation of the artefact. We can see that the lo-fidelity prototypes above are mainly freeform and are created so they look like handwritten prototypes, none-professionally drawn drawings. This is a positive thing as people don’t get scared of making changes. But once you want to make it a little more formal you need to factor in the point that people will be more resistant to change.

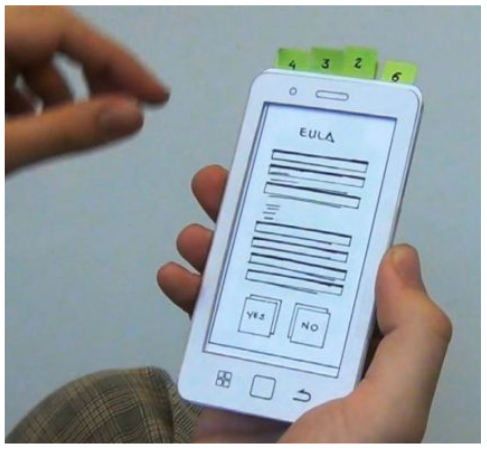

Initially, it’s still a person just drawing with a little linkage here and there. You shouldn’t undervalue this, the value of prototypes, especially of lo-fidelity prototypes is their ability to be changed by anyone (professionals and users alike). And so designers in large companies tend to use lo-fidelity prototyping. One example is the Nintendo Miiverse, one of the original Nintendo designs which utilises a three dimensional box that you hold and pull and push the cards from the top of it. Indeed, designer Kazuyuki Motoyama explains that the only way to actually know what a Miiverse would feel like was to hold it. That’s when he built this prototype out of cardboard.

9.2.1 Nintendo Miiverse

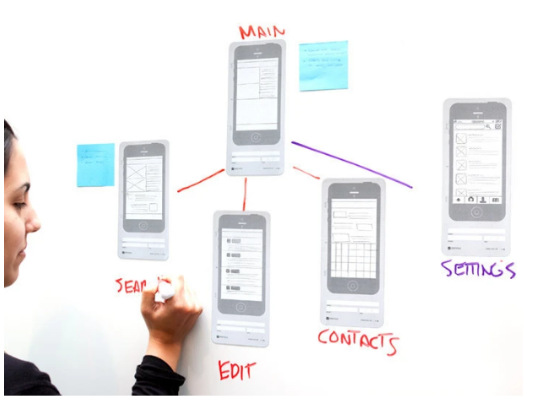

Miiverse was actually modelled on Wii U prototype (which was intended to be one conjoined system) three dimensional box that you hold and pull and push the cards from the top of it. So you can see exactly what will happen when a button is pressed. What’s more, oftentimes, you’re moving to a certain set of tasks so that you don’t get things wrong. So it will tell you what to do. For instance, if you press this button, this will happen. And then you reveal that by removing (or adding) the card. So you are if you like running it yourself, if you like you can get these kinds of index card templates, whereby you have the mobile app on them, and then you can spread them on your desk so that you can show people how things are going to happen, move these templates around, which is quite a nice way of doing it. Once you turn it over, it can tell you the kind of tasks and the things that are expected to be accomplished. And in some cases, it’s got a reverse. So you know, if you click a button you clicked over, and then it’s got the button clicked on the other side. So you can have different forms of this. But it’s all to get this kind of level and feeling of what this thing is going to be like.

9.3 Prototypes in Software Engineering

Being a software engineer, there’s always the desire in a lot of ways to just get moving, to get moving on the actual interface, don’t bother about design, just get moving on it, get something out there. That’s a useful way of doing it when you’re trying to get an idea about what it is that you’re trying to create. When you need to know something about the systems that you’re trying to create and what they’re trying to do. And if you don’t know that yet, then it can be problematic without an initial interface model.

Now, when we talk about cowboy coding, this is what we mean in a prototyping context. Agile presumes that you’ve got some idea about what it is you’re building, if you have no idea about what it is you’re building, then cowboy coding kicks in. We just start making lots of lo-fidelity prototypes out there trying to get people to use them and understand which is the best one, which isn’t without a real clear idea necessarily. But that’s because if you don’t have an idea about what’s required, or what you’re going to build, because it’s so novel, then you’ve got to find some way of doing it.

As we’re seeing, increasing development increases fidelity. Once we have moved along from lo-fidelity then we get into common graphics or flow charting apps, such as sketch, Illustrator and OmniGraffle. And these things can actually also generate some kind of metadata to allow you to better create the screens etc. And then we get to the high fidelity prototype, which is really just to all intents and purposes, a visual designer for a screen but without any data. And then you’re able to create the interface and screens and add dummy plug in data in the back of it.

We’re going to talk about the separation of concerns soon enough, however we can see how this might work in prototyping as the interface is separated from the data on the interface (and this data is the result of programme logic). When we think about separation of concerns, even in high fidelity prototypes, it allows us to create the interface for different targets, might be mobile, might be desktop, different kinds of targets, we create the prototype, we create the interface for that target, but then we need the actual programming logic. And so we can then build the programme logic at the back. And this is where it really is useful to have some kind of RESTful interface decoupling of the programme logic from the interface itself. Or aspects like micro services, whereby you can develop parts independently of the other parts of the system. So you can build it up in that kind of separated way.

People are excluded from hi-fidelity prototypes, because you need more knowledge of how to use tools, whereas lo-fidelity, you just need to know how to use paper and pen. It’s pretty ubiquitous currently. Lo-fidelity prototypes allows you to think with your hands and not be too bothered about what things might look like, and what decisions you’re making, because it’s easily changeable by rubbing out with a pencil with an eraser or scrubbing over a pencil and drawing the lines and that kind of thing. So it’s a lot easier to do. It allows you to to make lots of validation steps of what’s required with users very quickly within in the space of a few days, because you can make the changes very quickly.

| HIGH-FIDELITY PROTOTYPE | LOW-FIDELITY PROTOTYPE | |

|---|---|---|

| Interactivity | ||

| Clickable links and menus | Yes: Many or all are clickable. | No: Targets do not work. |

| Automatic response to user’s actions | Yes: Links in the prototype are made to work via a prototyping tool (e.g., InVision, PowerPoint). | No: Screens are presented to the user in real time by a person playing “the computer.” |

| Visuals | ||

| Realistic visual hierarchy, priority of screen elements, and screen size | Yes: Graphics, spacing, and layout look like a live system would look (even if the prototype is presented on paper). | No: Only some or none of the visual attributes of the final live system are captured (e.g., a black-and-white sketch or wireframe, schematic representation of images and graphics, single sheet of paper for several screenfuls of information). Spacing and element prioritization may or may not be preserved. |

| Content and Navigation Hierarchy | ||

| Content | Yes: The prototype includes all the content that would appear in the final design (e.g., full articles, product-description text and images). | No: The prototype includes only a summary of the content or a stand-in for product images. |

And it allows for ‘user centred design’ whereby the user is actually more part of the process. Because with user centred design, we want the users to be involved in the process, not excluded, and most users won’t have the skills to use SketchUp or OmniGraffle, or even the hi-fidelity generation engines. Further, they’re not as free in their designs if they have to have somebody else do that for them. So even though there might be two people together designing the system, users who wants the designer to make a change in a hi-fidelity prototype is going to be much more reticent because they think it will be more work.

9.4 Users, Commissioners, Engineers!

Prototypes are used with users, with commissioners, and with engineers and typically in that order from lo to hi fidelity. So what would normally happen is that you’d have users who would look at these lo-fidelity prototypes that have been drawn freehand (say) just written on post it notes, so you can move things around quickly, you might then firm that up into something that’s mid range. So it’s more along the lines of an actual computer generated hierarchy using SketchUp, etc, which is something that a lot of designers use in developing designs, and so you can see what’s going on at this stage. Now, remember, everything I’m talking about when it comes to prototypes is visual; I’m not talking about any prototypes for conversational interfaces, or zero UI, or auditory design, because most users don’t think about these aspects in the early stages of the design. So as you’re a UX’er, you’re going to have to think about how to do for non-visual prototyping because there’s no best practice out there.

So commissioners will expect the system to look more professional and they will be expecting to make minimal to no changes, however, it still might not be the final design. But with the engineers, you’re probably going to create something that’s the final thing, you’re probably likely to let the commissioners see that as well at one of the development meetings, but mainly then, with the engineers, you can make the changes and generate out something for the engineers to start work on.

As a UXer, you’re probably going to start work on the low fidelity prototypes and this is typically because you’re going to be working more with the users, once it gets to the visual designers, they’re going to be using mid range SketchUp like applications. So they’ll do the visual design there. Now translating that visual design to the hi, very hi-fidelity prototypes ready to generate out for the engineers might be your job again, because really, you’re translating the visual design into something that can then be created as the basis for code. Or it might be an engineer, or it might be a specialist visual designer.

9.5 Rapid Application Development

Rapid Application Development is really the boundary of these hi-fidelity prototype tools. And now, hi-fidelity prototyping tools have taken over the space of rapid application development. RAD was a 1991 era idea or at least it was expressed in that idea whereby we needed to create applications quickly without any sort of background machinery such that users could see what was going to be there and is heavily reliant on prototyping. And so this is kind of a method of doing the prototyping. In this case, RAD is a software development methodology that prioritizes speed and flexibility in delivering high-quality applications. It emphasizes rapid prototyping and iterative development cycles to quickly build and deploy software solutions. RAD aims to accelerate the development process, reduce time to market, and improve customer satisfaction by involving end-users and stakeholders throughout the development lifecycle. Key characteristics and principles of Rapid Application Development are

- Iterative Approach: RAD follows an iterative development model, where software is developed in small increments or prototypes. Each iteration focuses on specific features or functionalities, allowing for quick feedback and continuous improvement. This is a lot like the newer concept of Agile - which is now tied to UX.

- User-Centric Focus: RAD places a strong emphasis on user involvement. Users and stakeholders are actively engaged throughout the development process to gather requirements, validate prototypes, and provide feedback. This ensures that the final product meets user expectations and addresses their needs effectively.

- Prototyping: RAD heavily relies on prototyping techniques to rapidly build and refine software solutions. Prototypes are created early in the development process to demonstrate the application’s core functionality, interface, and user experience. User feedback is incorporated into subsequent iterations, leading to an evolving and user-centric design. This is the critically important part of RAD for UX and we might even extend this to imply that an initial software framework can be generated from a hi-fidelity prototype.

- Collaboration and Teamwork: RAD promotes close collaboration among developers, users, and stakeholders. Cross-functional teams work together to define requirements, design prototypes, and deliver working software in short development cycles. Effective communication and teamwork are crucial to the success of RAD projects.

- Reusable Components: RAD encourages the reuse of existing software components and modules. By leveraging pre-built components, RAD speeds up development and reduces the effort required to build certain features. This approach enhances productivity and allows developers to focus on unique requirements and functionality.

- Parallel Development: RAD enables parallel development activities by dividing the project into smaller modules or components. Different teams or developers can work on these modules simultaneously, ensuring faster development and integration of various software components.

- Flexibility and Adaptability: RAD emphasizes flexibility and adaptability to changing requirements. The iterative nature of RAD allows for adjustments and refinements based on user feedback and evolving business needs. This enables the software to evolve and align with changing market dynamics.

- Time and Cost Efficiency: By employing rapid prototyping, iterative development, and close collaboration, RAD can significantly reduce development time and costs. The focus on early user involvement and continuous feedback minimizes rework and ensures that the final product meets user expectations.

It’s important to note that RAD is not suitable for all types of projects. It is best suited for projects with well-defined scope, clear business objectives, and actively involved users and stakeholders. RAD is particularly effective in situations where time to market is critical or when requirements are subject to change.

Overall, Rapid Application Development offers a dynamic and flexible approach to software development, enabling faster delivery of high-quality applications while maintaining a user-centric focus. If you’re working in RAD (or at least a close variant), then you also need to make sure that the system you’re using will generate an application that can run and that can be populated with fake data, but that cannot have any real programme logic. For the interface, it will display content which is understandable by a user and it might also then have links to databases in the background and it can become increasingly complex as development and modelling proceeds. RAD is not just about user experience it’s also about any system development via higher level languages and so you can also generate, for instance, a database application via flowcharts via state transition diagrams via UML. So any system development will utilise RAD because it’s a faster transition from the design phase to the application phase.

9.5.1 RAD & Prototype Comparison

RAD and Prototyping are both software development approaches, but they differ in their objectives and the stages of the development process they focus on. However, there is clear linkage in that RAD heavily utilises prototyping and prototyping at the very hi-fidelity often include the ability to generate a working RAP prototype for user involvement and as a kickstart to the initial development effort.

9.5.1.1 Objectives

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD aims to expedite the development process by emphasizing iterative development and quick delivery of functional software. Its focus is on rapid iteration and user feedback to ensure that the final product meets user requirements.

- Hi-Fidelity Prototyping: Hi-Fidelity Prototyping focuses on creating highly detailed and interactive prototypes that closely resemble the final product. The goal is to test and validate the design and user experience before investing significant resources in development.

- Lo-Fidelity Prototyping: Lo-Fidelity Prototyping focuses on creating low-detail, basic prototypes that represent the core functionality of the final product. The goal is to quickly explore design concepts, test ideas, and gather early feedback before investing significant resources in development.

9.5.1.2 Development Process

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD typically follows a cyclic or iterative process, where each iteration involves requirements gathering, prototyping, development, testing, and deployment. The emphasis is on reducing the time between iterations to quickly deliver a working product.

- Hi/Lo-Prototyping: Hi/Lo-Fidelity Prototyping is usually an early stage in the development process. It involves creating detailed prototypes that simulate the functionality and user interactions of the final product. These prototypes are used to gather feedback and validate design decisions before moving to development.

9.5.1.3 Level of Detail

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD focuses on creating functional software quickly, often with a minimalistic user interface and core features. The emphasis is on delivering working software within short timeframes, allowing users to provide feedback and shape the development process.

- Hi-Fidelity Prototyping: Hi-Fidelity Prototypes are highly detailed and aim to closely resemble the final product in terms of user interface, interactions, and visual design. They often include realistic data and simulate real-world scenarios to provide a comprehensive user experience for testing and validation.

- Lo-Fidelity Prototyping: Lo-Fidelity Prototypes are intentionally low in detail, often using simple sketches, wireframes, or basic interactive mockups. They are not intended to replicate the final product’s design or functionality but rather to capture the basic structure and flow of the application.

9.5.1.4 User Feedback

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD encourages frequent user involvement throughout the development process. Users have the opportunity to provide feedback on the working software during each iteration, allowing for continuous improvement and alignment with their requirements.

- Hi-Fidelity Prototyping: Hi-Fidelity Prototypes are primarily used to gather user feedback and validate design decisions. Users can interact with the prototype, provide input, and offer suggestions for improvement before the development phase begins.

- Lo-Fidelity Prototyping: Lo-Fidelity Prototypes are often used to gather early feedback from stakeholders and users. Since they are low in detail, the focus is on validating and refining the overall concept, functionality, and user experience rather than specific design elements.

9.5.1.5 Time and Resource Investment

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD aims to deliver working software quickly, reducing time-to-market and allowing for faster user feedback. It requires a high level of collaboration, skilled development teams, and well-defined requirements to ensure efficient and rapid development.

- Hi-Fidelity Prototyping: Hi-Fidelity Prototyping requires significant upfront time and effort to create detailed and realistic prototypes. However, it can potentially save time and resources in the long run by identifying design flaws and usability issues early, before investing in full-scale development.

- Lo-Fidelity Prototyping: Lo-Fidelity Prototyping is relatively quick and inexpensive compared to other prototyping methods. It allows for rapid exploration of ideas and concepts without investing significant time and resources. However, it may require additional effort to translate the low-fidelity prototype into a high-fidelity design during the development phase.

In summary, RAD focuses on quickly delivering functional software with iterative user feedback, while Fidelity Prototyping emphasizes creating detailed and interactive prototypes for early validation of design decisions. The choice between the two approaches depends on the project requirements, timeline, and the level of detail and user involvement needed at each stage of development.

9.6 Summary

Though low-fidelity prototyping has existed for centuries, it has recently become popular with the spread of agile design methodologies, inspired by several movements including design thinking advocates for ‘thinking with your hands’ as a way to build empathetic solutions. Lean startup relies on early validation and the development of a minimum viable product to iterate on. User-centered design calls for a collaborative design process where users deliver continual feedback based on their reactions to a product’s prototype.

Prototypes are used by application/system users, commissioners, and engineers as part of the initial Design Phase, such that once requirements are collected and you want to convey information to Visual Designers or Software Engineers. As a UX’er you’ll probably mostly work with Low-Fidelity prototypes. Initial low investment of time which makes it very flexible and Iteratively evolves to be more like an app with a higher investment of time and therefore less flexibility. very hi-fidelity prototypes can often be ‘run’, and/or generate, a working framework, and it is at this point that RAD processes can be utalised. RAD demands frequent user interfacing, and is heavily reliant on prototyping.

Finally, remember, ‘A process that is not critically dependent on prototyping is not a UX process.’ — Julian Caraulani, Senior UX Designer at Samsung.

9.6.1 Optional Further Reading

- [Ben Coleman and Dan Goodwin (2017)] — Designing UX: Prototyping. SitePoint. 978-0994347084.

- [Reinhard Sefelin, et al (2003)] — “Paper prototyping - what is it good for?: a comparison of paper- and computer-based low-fidelity prototyping”. CHI ‘03 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM: 778–779. doi:10.1145/765891.765986. ISBN 978-1581136371. S2CID 275647

- [Nick Babich (2020-09-25)] — The Magic of Paper Prototyping. Medium. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- [Steve McConnell (1996)] — Rapid Development: Taming Wild Software Schedules, Microsoft Press Books, ISBN 978-1-55615-900-8

- [James M. Kerr & Richard Hunter (1993)] — Inside RAD: How to Build a Fully Functional System in 90 Days or Less. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-034223-7.

- [James Martin. (1991)] — Rapid Application Development. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-376775-8.