10. Principles of Effective Experience (Accessibility)

While pedalling a Boris Bike I start to shuffle in my pocket. Where is that damn iPhone? Finally, I find it. The next challenge is to get it out my pocket whilst still navigating the Humvee of the bike world. Eventually, I give up. I pull over and get my iPhone out. I look up the nearest docking station with spaces and get back on my way.

– LondonCyclist

This is an example of ‘situational impairment’ a barrier to access, the inability to produce or accomplishing the intended effect; in short non-effectual use.

10.1 Effective7, effectual8, accessible9

To my way of thinking these three terms mean the same thing, and, in reality, were going to be talking about accessibility. However, you should be thinking of accessibility in the more general terms of effective or effectual use, because the concept of accessibility is much broader than the narrow confines of disability it is often associated with [9241-129:2010, 2010].

This notion of the situationally-induced impairment, by which they do not mean an actual impairment of the person directly, but indirectly by the computational device or the environment in which it must be used. They point out that non-disabled individuals can be affected by both the environment in which they are working and the activities in which they are engaged, resulting in situationally-induced impairments. For example, an individual’s typing performance may decrease in a cold environment in which one’s finger does not bend easily due to extended exposure at low temperature. Or the similarities between physical usability issues on both small devices, such as a Mobile Telephone, Personal Digital Assistant, or any other hand-held device with a small keyboard and display, and accessible interaction scenarios. This means that by making your interfaces accessible, you can transfer accessibility solutions into the mobile and situational context.

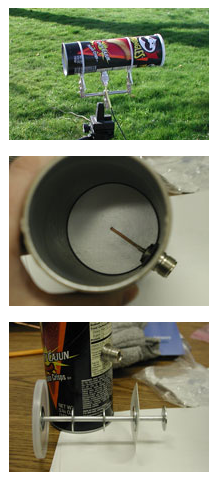

This support for situational impairments, through flexibility, adaptability, and the ability to personalise the user experience, in other words transformable UIs, is important for access in developing regions too. Web use in developing regions is currently characterised by constrained operating modalities. Slow speed, low computational power, reduced bandwidth, compact keyboards, small screens, and limited power, all compound the problem of access and inclusion. In addition, interaction is sometimes without conventional written language and illiteracy is also a barrier to information and services. However, the benefits of technology are so great that the peoples of these regions often adopt resourceful methods of interaction and access sometimes repurposing resources so that they are put to a different use than for which they were intended. The most obvious example was noted when Nokia sent a team to Africa and realised that people were using mobile phones, able to connect to a carrier or not, as a torch (see Figure: Nokia Torch). There is also the well-known use of Pringle tubes to direct a single point of wifi around a village community (see Figure: Pringle Tube Antenna); as well as other novel work which is less high-tech [Zobel, 2013]

So how can we develop effective user experiences? Well openness comes to our rescue – as do Sony Ericsson10, and Little Fluffy Toys Ltd11 – with Sony’s LiveView and Little Fluffy Toys’ Cycle Hire LiveView Gadget (see Figure: LiveView Cycle Gadget) “Using Bluetooth, the Live View gadget connects to your Android phone (2.0 or later). You can then do cool stuff such as check out the latest tweets, SMS messages, Facebook messages, take pictures remotely or, find the nearest Boris Bike docking station.” Problem solved! By taking account of the inability for the cyclist to access data on a conventional device using a conventional computer system, the engineers have created an accessible product; because the key to accessibility and effectual use is a focus on the user, and their personal needs. But to address these needs, needs which you may not understand or have experience with, you must think (like the Sony UX’ers) about extensibility and adaptability, ergo personalisation and openness of both the data, and the APIs to access it. By making sure that the system is open, and that aspects of the interface and human facing system components can be modified, adapted, or interacted with via an API, the developer is making an explicit statement which allows for extensibility. This means that all aspects of the application can be modified and changed once further information comes to light or in the event of processes in the organisational systems of the commissioner changing.

Accessibility aims to help people with disabilities to perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the computer system or interface. There are millions of people who have disabilities that affect their use of technology12. Currently most systems have accessibility barriers that make it difficult or impossible for many people with disabilities to use their interfaces [Kirkpatrick et al., 2006] Accessibility depends on several different components of development and interaction working together, including software, developers, and users. The International Standards Organisation (ISO) 9241-171:2008 [9241-171:2008, 2010] which covers issues associated with designing accessible software for people with the widest range of physical, sensory and cognitive abilities, including those who are temporarily disabled, and elderly people. There are also other organisations that have produced guidelines, but, the ISO guidelines are more complete and cover the key points of all the others. There are however, no homogeneous set of guidelines that developers can easily follow. Disabled people typically use assistive technologies, hardware and software designed to facilitate the use of computers by people with disabilities, to access interfaces in alternative forms such as audio or Braille.

Pre-eminent when discussing accessibility is visual impairment and profound blindness, however, it should be remembered that visual disability is just one aspect of accessibility and technology. Other disabilities also exist which require changes to technology to enable a greater degree of accessibility. Before considering these, though, it is important to consider just what accessibility really means and why it is necessary to think about ‘access’ when building interfaces. Many disabled users consider technology to be a primary source for information, employment and entertainment. Indeed, from questioning and contact with many disabled users we have discovered that the importance of technology cannot be under-estimated.

“For me computer systems are everything. They’re my hi-fi, my source of income, my supermarket, my telephone. They’re my way in.”

This quote, taken from a blind user, sums up the sentiments we experience when talking with many disabled users and drives home the importance of accessibility in the context of independent living. Indeed, by making technology accessible, we help people live more productive lives.

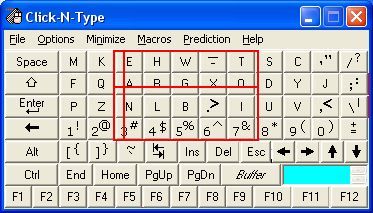

So how does this work in practice? Disabled users, use intermediate technologies to provide access to technology and computer functionality. In general this technology exists to provide access to any generic software on the computer, however this is not always the case for specialist systems. These ‘Assistive Technologies’ form a bridge from the user to the computer, much like a keyboard and monitor, the keyboard provides input, the monitor, output. In the case of say physical disability the input device, the keyboard, is not accessible to the user and so a software keyboard is substituted. This keyboard can then be tailored depending on the physical characteristics of the user. A mouse or joystick may be used to place the cursor, or a simple switch is used to interact with a software keyboard exhibiting a ‘scanning’ behaviour. However, some technology tends to be seen as a special case, this means that in some cases assistive technology exists as a solution just to the unique problems found when interacting with specialist systems as opposed to more general system accessibility [Harper and Yesilada, 2008]. Most assistive technology focuses on output, and so assistive technology for users with input problems, such as profound physical disability, tends to be focused on the computer and software in general and does not normally impact on specialist accessibility domains, such as Web accessibility. This output accessibility is developed independently along two fronts, both as part of interface design along with assistive technology on the user’s computer. However, due to the design effort needed to build interfaces, the focus is primarily on the accessibility of the interaction or the tailoring of the interactive components to a specific audience. Indeed, this latter case tends to be the focus of accessibility for cognitive disability and hearing impairment.

It is my firm belief that internationalisation, also known as I18n, and culture can be barriers to the accessibility of software and so could be addressed under the border category of accessibility. However in most contexts internationalisation along with localisation are mainly seen as technical issues requiring multilingual translation of language components. Indeed, in this regard culture, which can also be a barrier to access, is often not addressed at all. For instance, in the mid-90s some users of the World Wide Web did not want to select the hyperlinks. This was because the links were blue, and blue was seen as a inauspicious colour. So then, internationalisation, in the broader sense, is the design and development of a product, application or interfaces that enables easy localization for target audiences that vary in culture, region, or language. In effect this means enabling the use of Unicode, or ensuring the proper handling of legacy character encodings where appropriate, taking care over the concatenation of strings, avoiding dependence in code of user-interface string values, or adding support for vertical text or other non-Latin typographic features. This also means enabling cultural conventions such as supporting: variance in date and time formats; supporting local calendars; number formats and numeral systems; sorting and presentation of lists; or the customary handling of personal names and forms of address.

In summary, there is no ‘catch–all’ solution to providing accessibility to computer-based resources for disabled users. Each disability requires a different set of base access technologies and the flexibility for those technologies to be personalised by the end–user. To date, the main focus has been on visual impairment. However, there are moves to address accessibility for hearing and cognitive impairments. Effective interaction, with the computer system or interface, requires that firstly the system can be accessed, secondly, that once accessed the system can be used effectively, and thirdly, that once used effectively the experience of usage is pleasurable and familiar. Keeping in mind, these three overriding priorities will enable you to design better interfaces and interactive environments for the user.

10.2 Barriers to Effectual Use

Often, when we start to build interfaces or design systems we can find it helpful to place ourselves at the centre of the process. Designing for ourselves enables us to think more easily about the problems at hand, and the possible cognitive or perceptual aspects that the interface will be required to fulfil [Chisholm, 2008]. While this is perfectly acceptable as a way of creating an initial prototype. Indeed, this is becoming increasingly know as ‘Autobiographical Design’ [Neustaedter and Sengers, 2012, Neustaedter and Sengers, 2012a] – it is not acceptable as the design progresses. This is because there are many different kinds of people and these people have many different types of sensory or physical requirements; indeed, this is where scenarios and personas come in handy. Remember, it is your job to understand these requirements and keep them mind in all aspects of your interface or system designs.

10.2.1 Visual Impairment

Blindness, visual disability, visual impairment, or low vision means that the user will not be able to make adequate use of visual resources. In most cases blindness does not mean that the user can see absolutely nothing, but that aspects of their vision do not work correctly and cannot be corrected with lenses. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines low vision as visual acuity13 of less than 6/18 (20/60), but equal to or better than 3/60 (20/400), or corresponding visual field loss to less than 20 degrees, in the better eye with best possible correction. Blindness is defined as visual acuity of less than 3/60 (20/400), or corresponding visual field loss to less than 10 degrees, in the better eye with best possible correction. This means that a legally blind individual would have to stand around three metres from an object to see it. According to the most recent estimates of the global burden of visual impairment, more than 161 million are blind. This means that if we are to support users with low vision or blindness we need to make sure that two things can happen when thinking about the interface. The first is that the screen can be magnified and that components which are necessary for interaction can be located in a physically similar location so that, when zoomed, they are usable together. Secondly, the interface should conform to general accessibility guidelines and principles meaning that each visual object has a corresponding textual description, and that the textual description can be accessed.

10.2.2 Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment, also associated with learning difficulties, is one of the most pernicious barriers to human interaction with computers. This is mainly because aspects of cognitive disability not yet well understood and the spectrum of cognitive disability is so widespread that simply following a set of design criteria cannot assist in creating interfaces suitable for users with cognitive and learning impairments. It is therefore difficult to present any accurate figures relating to cognitive impairment as they change so rapidly and the definition is in some cases fluid. In general, users with cognitive impairments may have difficulties with executive function, memory, attention, visual and spatial perception, language, and emotions. Indeed it is more likely, that to a greater or lesser extent, minor aspects across most of these categories may be present. However, studies conducted in the USA, suggest that around 56% of people with cognitive impairment do enter the labour market and of those a fair percentage are employed in the use of computation devices. Therefore, the UX’er must also keep in mind the needs of this type of user when building systems interfaces; paying particular attention to learnability. Indeed, one of the key things to remember when designing interfaces and systems is to try and use as simple a language as possible, and where appropriate, annotate the interface with consistent graphical symbols.

10.2.3 Hearing Impairment

Hearing impairment is a broad term used to describe the loss of hearing in one or both ears. Hearing impairment refers to complete or partial loss of the ability to hear, with the level of impairment being either mild, moderate, severe or profound. Deafness, on the other hand, refers to the complete loss of ability to hear from one or both ears. Of the two types of hearing impairment, Conductive and Sensorineural. Conductive occurs when there is a problem conducting sound waves anywhere along the route through the outer ear, tympanic membrane (eardrum), or middle ear (ossicles). Where Sensorineural is usually permanent, and is caused by excessive noise or ageing, and requires rehabilitation, such as with a hearing aid. According to WHO estimates, 278 million people worldwide have moderate to profound hearing loss in both ears, with many living in low to middle-income countries. Also, the number of people worldwide with all levels of hearing impairment is rising. This is mainly due to a growing global population and longer life expectancies within those populations. In this case there are a number of aspects to consider when thinking about the user interface. Using sound alone to convey status information is inappropriate, indeed, relying solely on audio to convey any information should be avoided. Where possible captioning and text should be used. However, the UX’er should also remember that written or spoken language is not the native language of hearing-impaired users. In this case, sign language has become the accepted form of communication within this community, and indeed sign language is also a cultural requirement for many hearing-impaired or deaf users. Communication then, within the deaf community can be thought of as a combination of internationalisation and culture.

10.2.4 Physical Impairment

Physical Impairment affects a person’s ability to move, and dexterity impairments are those that affect the use of hands and arms. Depending on the physical impairment, there are many challenges that affect users’ interaction such as pointing to a target or clicking on a target. There are two kinds of impairments that affect interactivity: (a) musculoskeletal disorders that arise from loss, injury or disease in the muscle or skeletal system such as losing all or part of a hand or arm; and (b) movement disorders that arise from a damage to the nervous system or neuromuscular system such as Parkinson’s disease which cause slowness of movement. Physical impairment is widespread mainly because many factors can bring on its onset. Indeed, one of the largest surveys conducted in the United Kingdom estimated that 14.3% of the adult population had some mobility impairment that includes locomotion, reaching and stretching and dexterity. You should realise that people with motor impairments use a variety of creative solutions for controlling technology. These include solutions such as alternative keyboards and pointing devices, voice input, keyboard-based pointing methods and pointing based typing methods. Indeed, it can be seen that some of these solutions are also useful for users without a physical impairment, but who may be hindered by the size of their computational device or the environment in which it must be used.

10.2.5 Situational Impairment

Situational Impairment is not actually an impairment of the person directly, but indirectly by the computational device or the environment in which it must be used. Situation impairment is a recent phenomenon, indeed, it was first defined by Sears and Young in 2003. They point out that non-disabled individuals can be affected by both the environment in which they are working and the activities in which they are engaged, resulting in situationally-induced impairments. For example, an individual’s typing performance may decrease in a cold environment in which one’s finger does not bend easily due to extended exposure at low temperature. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that there are strong similarities between physical usability issues in both small-devices, such as a Mobile Telephone, Personal Digital Assistant, or any other hand-held device with a small keyboard and display, and accessible interaction scenarios. Both small-devices and accessible interfaces share the need to support various input techniques; they both benefit from flexible authored and accessible interfaces, and text entry and navigation in both scenarios are slow and error-prone. As a UX specialist, we can assume that different forms of disability have similarities with common situational impairments present in mobile situations. Many factors may, therefore, affect how users interact with mobile interfaces and these must be taken into account when building interfaces for these kinds of interactive scenarios.

10.2.6 Combinatorial Impairment

Population demographics indicate that our populations are ageing across the board. Indeed, the world’s older population is expected to exceed one billion by 2020. Evidence suggests that approximately 50% of the older population suffer from impairments, such as hearing loss, with one in five people over the age of 65 being disabled. As the population ages the financial requirement to work more years is increased, but age-related disability becomes a bar to employment. At present, only 15% of the 65+ age-group use computers, but as the population ages this number will significantly increase. An ageing, but computer literate, population indicates a large market for computer-based services especially when mobility is a problem for the user. In many developed countries, the growth of the knowledge economy and a move away from manual work should improve the prospects of older Web users being able to find employment, providing technology, and specifically computational resources, is accessible to them. The aspects of impairment that define ageing is those of a combinatorial nature. In effect, ageing users have problems found in one or more of the groups listed in this section, but often, these impairments are less severe but more widespread.

Hummmm… In the paragraph above I imply ageing is a barrier and combinatorial disabilities are its cause. But am I right to make such sweeping generalisations, swept along by a prevailing western research mindset14 [Lunn and Harper, 2011]?

Well, my mind drifted back to a paper by Peter G. Fairweather from IBM T.J. Watson called ‘How older and younger adults differ in their approach to problem-solving on a complex website’.

Peter challenges the view that *“Older adults differ from younger ones in the ways they experience the World Wide Web. For example, they tend to move from page to page more slowly, take more time to complete tasks, make more repeated visits to pages, and take more time to select link targets than their younger counterparts. These differences are consistent with the physical and cognitive declines associated with ageing (sic).

The picture that emerges has older adults doing the same sorts of things with websites as younger adults, although less efficiently, less accurately and more slowly.”* He presents new findings that show that *” to accomplish their purposes, older adults may systematically undertake different activities and use different parts of websites than younger adults. We examined how a group of adults 18 to 73 years of age moved through a complex website seeking to solve a specific problem.

We found that the users exhibited strong age-related tendencies to follow particular paths and visit particular zones while in pursuit of a common goal. We also assessed how experience with the web may mediate these tendencies.”* [Fairweather, 2008]

The interesting part is that Peter finds that younger and older people do things differently with older users taking a less risky route, but also that experience, not age, is the defining factor of regarding how to solve the assigned problem using the web. Younger inexperienced users make more mistakes than older experienced users and take longer. So what does this say about our conception of older users having problems found in other disability groups – ageing as disability, ageing as impairment?

I’m beginning to think that ageing, in general, isn’t a barrier to access although combinatorial disability – at whatever age it occurs – may well be. But it is true that low-level combinatorial impairments affect older users more, proportionally than others. However, in all cases, a lack of experience and knowledge are much more significant barriers to access, so education is key. It seems we have got into a habit of using ageing as a proxy term for combinatorial disability, its inaccurate and we should stop it.

10.2.7 Illiteracy

Education is the key to Illiteracy. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) defines literacy as ‘The ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, compute and use printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning to enable an individual to achieve his or her goals, to develop his or her knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in the wider society.’ Literacy comprises a number of sub-skills, including phonological awareness, decoding, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary. Mastering each of these sub-skills is necessary for learners to become proficient readers. However, literacy rates can vary widely from country to country or region to region. This often coincides with the region’s wealth or urbanisation, though many factors play a role, such as social customs and education. As a UX specialist you must be aware that it is possible your software may be used in circumstances where illiteracy is prevalent. Indeed, studies suggest that around 20% of the world’s population are illiterate and so there is a high chance that your software will be used by someone who will have some difficulty in understanding the labels, prompts, textual components, or content of the interface. In this case you should try to anticipate this aspect by adding images and sound, and making the interface as flexible as possible so that it can be more easily adapted to the users needs.

10.2.8 Developing Regions

Computer use in developing regions is currently characterised by constrained operating modalities. Slow speed, low computational power, reduced bandwidth, compact keyboards, small screens, and limited power, all compound the problem of access and inclusion. Also, interaction is sometimes without conventional written language and illiteracy is also a barrier to information and services. However, the benefits of computer technology are so great that the peoples of these regions often adopt resourceful methods of interaction and access sometimes repurposing technical equipment so that it is put to a different use than for which it was intended and sharing access often on a community-wide basis. While computational use in developing regions may not seem directly related to user experience, the interface considerations and its adaptability are important within this context and do indeed speak to the wider human factors domain. In this case, it is useful to keep in mind the possible problems that may be encountered in constrained operating modalities and the possible requirements for interface adaptation.

10.2.9 Exclusion

The opportunities created by digital technologies are not enjoyed by the whole of society, indeed, there is a strong correlation between digital exclusion and social exclusion. There are significant and untapped opportunities to use technology better on behalf of citizens, communities, and digitally disenfranchised groups. However to achieve inclusion, systems must be created seeing the human factor as a part of an integrated solution from the outset, not as an adjunct but also not as a focus. In addition, the multiplicity and ubiquity of devices and their interfaces are key to successful inclusion, and systems must be tailored to what users require and will use; as opposed to what organisations and government require and use.

10.3 Technical Accessibility Issues

As we have already discussed, pre-eminent when discussing accessibility is visual impairment and profound blindness. However, it should be remembered that visual disability is just one aspect of software accessibility. Other disabilities also exist which require changes to the interface to enable a greater degree of accessibility. Since the 1980s, visually impaired people have used computers via screen-readers. During the 1980s, such applications relied on the character representation of the contents of the screen to produce spoken feedback. In the past few years, however, the widespread trend towards the development and use of the GUIs has caused several problems for profoundly blind users. The introduction of GUIs has made it virtually impossible for blind people to use much of the industry’s most popular software and has limited their chances for advancement in the now graphically oriented world. GUIs have left some screen-readers with no means to access graphical information because they do not use a physical display buffer, but instead, employ a pixel-based display buffering system. A significant amount of research and development has been carried out to overcome this problem and provide speech-access to the GUI. Companies are now enhancing screen-readers to work by intercepting low-level graphics commands and constructing a text database that models the display. This database is called an Off-Screen Model (OSM), and is the conceptual basis for GUI screen-readers currently in development.

An OSM is a database reconstruction of both visible and invisible components. A database must manage information resources, provide utilities for managing these resources, and supply utilities to access the database. The resources the OSM must manage are text, off-screen bit maps, icons, and cursors. Text is obviously the largest resource the OSM must maintain. It is arranged in the database relative to its position on the display or to the bit map on which it is drawn. This situation gives the model an appearance like that of the conventional display buffer. Each character must have certain information associated with it: foreground and background colour; font family and typeface name; point size; and font style, such as bold, italic, strike-out, underscore, and width. Merging text by baseline (i.e. position on the display) gives the model a ‘physical-display-buffer’ like appearance with which current screen-readers are accustomed to working. Therefore, to merge associated text in the database, the model combines text in such a way that characters in a particular window have the same baseline. Each string of text in the OSM has an associated bounding rectangle used for model placement, a window handle, and a handle to indicate whether the text is associated with a particular bit map or the display. GUI text is not always placed directly onto the screen. Text can be drawn into memory in bit-map format and then transferred to the screen, or can be clipped from a section of the display and saved in memory for placement back onto the screen later.

In windowing systems, more than one application can be displayed on the screen. However, keyboard input is directed to only one active window at a time, which may contain many child windows; the applications cursor is then placed in at least one of these child windows. The OSM must keep track of a cursor’s window identification (i.e. handle) so that when a window becomes active the screen-readers can determine if it has a cursor and vocalise it. Additionally, the OSM must keep track of the cursor’s screen position, dimensions, the associated text string (i.e. speak-able cursor text), and character string position. If the cursor is a blinking insertion bar, its character position is that of the associated character in the OSM string. In this case, the cursor’s text is the entire string. A wide rectangular cursor is called a selector since it is used to isolate screen text to identify an action. Examples of selector cursors are those used for spreadsheets or drop-down menus. The text that is enclosed within the borders of the selector is the text that the ‘Screen Reader’ would speak.

Modifying current screen-readers to accommodate the new GUI software is no easy task. Unlike DOS, leading GUI software operates in multitasking environments where applications are running concurrently. The screen-reader performs a juggling act as each application gets the user’s input. However, many frameworks and application bridges have been created to help the operating system accomplish this ‘juggling’.

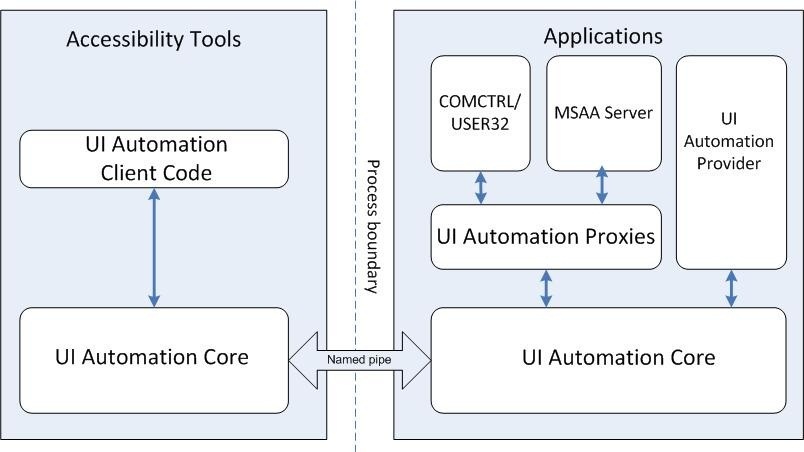

10.3.1 MSAA and UIA

Microsoft Active Accessibility (MSAA) is a developer technology that improves the way programs and the operating system work with accessibility aids. MSAA can help software developers make their programs more compatible with accessibility aids, and accessibility aid developers can make more reliable and robust aids. MSAA is an underlying technology that is invisible to users and provides a standard way for accessibility aids to obtain information regarding user interface elements. This standardisation helps software developers and assistive technology developers alike to ensure their products are compatible mainly on the Windows platform. This standard also gives software developers more flexibility in designing their application interfaces by understanding the needs of assistive technologies. In this way, UX specialists can innovate more freely without sacrificing compatibility and have the confidence that the underlying application logic and interface routines will integrate into the accessibility frameworks used by assistive technology developers. Microsoft UI Automation (UIA) (see Figure: Interaction Schematics for Microsoft’s ‘UI Automation’) is similar to MSAA in that it provides a means for exposing and collecting information about user interface elements and controls to support user interface accessibility and software test automation. However, UIA is a newer technology that provides a much richer object model than MSAA and is compatible with new Microsoft Technologies such as the ‘.NET’ Framework.

10.3.2 IAccessible2

IAccessible2 is a new accessibility API, which complements Microsoft’s earlier work on MSAA which fills critical accessibility API gaps in MSAA by combining it with the UNIX Accessibility ToolKit (ATK). A detailed comparison of MSAA to ATK revealed some missing interfaces, events, roles and states within the MSAA framework and so IAccessible2 was created out of a desire to fill these gaps. Therefore, IAccessible2 is an engineered accessibility interface allowing application developers to use their existing MSAA compliant code while also providing assistive technologies access to rich document applications. IAccessible2’s additional functionality includes support for rich text, tables, spreadsheets, Web 2.0 applications, and other large mainstream applications. In this case the Linux Foundation’s Open Accessibility Workgroup summarises IAccessible2 this as “complementing and augmenting MSAA by responding to new requirements; it was designed to enable cost effective multi-platform development; it supports Web 2.0 (AJAX, DHTML); it is a proven solution; its effectiveness has been demonstrated on both sides of the interface, by large applications like the IBM Workplace Productivity Editors and Firefox and by the leading AT vendors; and finally, it is a royalty free and open standard, free for use by all, open for review and improvement by all.” In this case, it seems more appropriate that software developers think seriously about using IAccessible2 as a means of providing accessibility at the interface level.

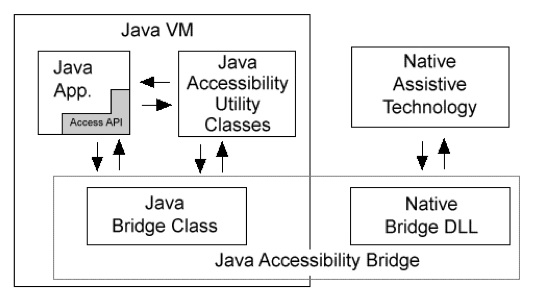

10.3.3 Interface Bridges

In an attempt to solve the accessibility problems of assistive technology and platform independent software, Sun Microsystems (Sun – now Oracle) introduced the Java Accessibility API, which was designed as a replacement for the OSM. With a Java application that fully supports the Java Accessibility API, no OSM model is necessary because the aim of the API is to provide all of the information normally contained in an OSM. For existing assistive technologies available on host systems (e.g. Microsoft Windows, OSX, Linux) to provide access to Java applications, they need some way to communicate with the Java Accessibility support in those applications. The Java Accessibility Bridge supports that communication. The Access Bridge (see Figure: JVM, Java Accessibility API and Access Bridge) makes it possible for an OS based assistive technology like JAWS to interact with the Java Accessibility API. The Java Accessibility API is implemented in the Swing user interface components. The Access Bridge is a class that contains ‘native methods’, indeed, part of the code for the class is actually supplied by a dynamically linked library (DLL) on a Windows host system. The assistive technology running on the host communicates with the native portion of the bridge class. This bridge class in turn communicates with the Java Virtual Machine, and from there to the Java Accessibility utility support and on to the Java Accessibility API of the individual user interface objects of the Java application it is providing access to.

The Java Accessibility API defines a contract between individual user-interface components that make up a Java application and an assistive technology that is providing access to that Java application, through the Accessible interface. This interface contains a method to get the AccessibleContext class, which contains the common core set of accessibility information that every user-interface object must provide. If a Java application fully supports the Java Accessibility API, then it should be compatible with assistive technologies such as screen-readers. For example, in order for ‘JAWS to provide access to Java applications running on Microsoft Windows, it would make calls to the Java Accessibility Bridge for Windows. When the user launches a Java application, the bridge would inform JAWS of this fact. Then JAWS would query the bridge and the bridge would in turn forward those queries on to the Java Accessibility Utilities that were loaded into the Java Virtual Machine. When those answers came back to the bridge, the bridge would forward them on to JAWS.

10.3.4 Platform Independent Software

We can see that the problem of platform independent software is easily surmountable by using technologies like the accessibility API and Bridge, but faults persist. The nub of the problem of platform independent developments is the fact that an additional level of indirection is present when compared with native developments. With a native development information regarding text, titles, window, and component status are implicitly accessible by the native OS and so in many cases this information does not need to be explicitly provided. This is not the case with platform independent software. In this case, the bridge component provides an intermediary step by implementing an OS native end along with a conduit to the Java native end. However, the application still cannot correctly resolve accessibility information unless it is made explicit. In summary, the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), Java Accessibility API, and the Java Access Bridge work together with the host system to provide the relevant information to an assistive technology. Because ‘implicit’ hooks are not available, a failure at the programming level to make information explicit can invalidate the entire pipeline and break the accessibility of the application. As we are seeing an increase in platform independent languages, such as ‘Ruby’, ‘Tcl’, ‘Perl6’, and the like, the software engineer and UX’er must be aware of the additional programming and testing required to make the interface accessible.

10.4 Potted Principles of Effectual User Experience

Conforming slavishly to a set of principles or success/conformance criteria – with our brain switched off – is never going to be a good idea. Indeed, it is such a bad idea that heuristic evaluation was created, to catch the errors introduced while trying to conform in the design and build phase. This said principles were useful if applied from a high level, and success criteria at a low level, or a least as cues you should be thinking about as you go through the design and development process. These are useful and will eventually reduce the number of negative user experiences encountered within the testing and validation phase.

There are many different principles and conformance criteria ranging from those described in the common texts to those described in the international standards [9241-20:2008, 2008]. Indeed, standards documents seem to be very in-depth and have many checkpoints and bulleted lists that you must individually assess and validate, common texts seem to specify only high-level principles without the detail covered in the standards documents. In this case there seemed to be no middle path. However, it is my opinion that the high-level principles can be discussed and accompanied with a series of questions the UX’er can keep in mind as the design and development proceeds. In this way, a constant mental questioning-framework is built in the UX’ers psyche which enables flexible critique based on the principles.

In my opinion that the most important considerations for effective and accessible interactions are those of openness, perceivability, operability, understandability, and flexibility. Keeping these five principles in mind – along with the questions accompanying each principal – will enable you to better: conform your designs and developments to acknowledged good practice, maintain your questioning nature, and be able to retrospectively apply these principles when it comes to heuristic evaluation and software audits.

However, you must remember that experience is everything. The way to truly understand these principles, and the questions contained within them, is to apply them in real life, develop them in real life, and test them in real life. Remember, memorising these principles does not make you an expert, applying them many times does.

10.4.1 Facilitate Openness

By making sure that the system is open, and that aspects of the interface and human facing system components can be modified, adapted, or interacted with via an application programming interface (API), the developer is making an explicit statement which allows for extensibility. This means that all aspects of the application can be modified and changed once further information comes to light or in the event of processes in the organisational systems of the commissioner changing (for example see Figure: Durateq ATV).

Open software means that bugs can be more easily fixed by an army of interested parties who may also want to use the software for their own purposes. Additions to the system can also back-flow to the originators work such that an enhanced system can be created without any additional effort on the originators part. Obviously there are problems with systems which the commissioner requires to be closed or which uses proprietary or bespoke data formats and interface specifications. However by leaving the system open to an extension, the developer can ensure a fast turnaround on any recommissioned work.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- If you have provided succinct, meaningful name and label for each interface component – including alternatives for icons, and the like – are these names displayed and available to third-party technology?

- Is your software open such that its information is available to third part systems including conventional assistive technologies?

- Does your software allow input and manipulation by these third party systems?

- If your systems are closed then, does it allow all input and output to pass through to third-party software?

10.4.2 Facilitate Perceivability

Critically, the user interface and human facing aspects of the development should be perceivable by many different types of user (for example see Figure: A Braille Display). It is obvious that the general software engineer cannot account for all aspects of perception and personalisation that may be required by an individual user. However, by ensuring that all information regarding interfaces components, the presence of alternative descriptions for specific widgets or components, and that this text has some semantic meaning, the developer can make sure that tools to translate between a standard interface and one which may require modification can occur much more easily.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Does your system convey information by colour alone (such as a button turning red) but without an alternate textual description?

- Is there a succinct, meaningful name and label for each interface component – including alternatives for icons, and the like?

- Can the user personalise the interface settings, including different styles and sizes of typography, fore and background colours, and default interface look and feel?

- How easy is it to find and interact interface controls and the shortcuts to them?

- Have you provided keyboard focus and text cursors, and will your system restore its previous state when regaining focus?

10.4.3 Facilitate Operability

As with perceivability, operability is also very important. As a UX’er you should realise there are many different kinds of user requirements when it comes to interfacing with the software. However, most systems which enhance or override standard operability systems use the keyboard buffer as a universal method of input. In this case you should make sure that all aspects of the functionality of the software, including navigation and control of the components, can be controlled via a series of keystrokes. For instance I am currently dictating this section, which means that I must have the Mac OS X accessibility extensions switched on, then the speech software can translate my speech into keystrokes and places those keystrokes within the keyboard buffer. To the application it seems as though someone is typing using the keyboard and therefore all interaction is handled accordingly. By supporting operability, device manufacturers can be assured that your software is operable regardless of the input modality.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Can the user control all aspects of an audio - visual presentation (such as a video)?

- Can the user personalise the interaction settings, and change the length of any timed events?

- Are all functions/interface components/interactions able to be controlled via the keyboard?

- Are all functions/interface components/interactions able to be controlled via a mouse-like pointer controller?

- Are all multiple chorded key presses available in a sticky-key sequential form?

- Can the keyboard be remapped?

- Have you provided keyboard focus and text cursors, and will your system restore its previous state when regaining focus?

10.4.4 Facilitate Understandability

Systems need to be understandable. This is especially important when it comes to the interface and the language used within that interface, including error messages, exception handling, and the system help. Using language that is simple to understand and supporting foreknowledge as to the outcomes of various choices the user may be asked to make; will assist in how usable the system becomes and performance increases. In this case, the systems developers should use jargon-free language that can be easily understood by the layperson and that has been tested with people who do not have a direct understanding of the computational aspects of the system. However, there are exceptions to this rule. Consider a bespoke piece of software created for an organisation that has a set of specific institutional abbreviations along with a specific knowledge of what these abbreviations, or linguistic shorthand, means. In this case, it may be appropriate to use terminology that is familiar to organisational users of the system but would be unfamiliar to a wider audience. In reality, interfaces are understandable if computational and developmental jargon is not used and if there is a clear statement as to the outcome is of any actions or decisions that the user is required to make. Further, the concept of ‘affordances’ [Gibson, 1977] – the quality of an object, or an environment, which allows an individual to perform an action (a knob affords twisting, a cord affords pulling) – can also be useful for implicitly/tacitly conveying information.

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Is there a succinct, meaningful name and label for each interface component – including alternatives for icons, and the like?

- Are all interface control and interaction features well documented?

- Do all error or alert messages give consistent information, appear in a consistent place, and facilitate movement to the site of those errors?

- Do you follow the OS keyboard conventions and best practice and style guides?

- Have you tied into the system wide spell checker?

10.4.5 Facilitate Flexibility

We cannot always plan and understand all possible actions and eventualities that will be required by an interface. Users are highly personal and the interactive requirements are different between users and also change over time for individuals. Requirements for the system may also change and requirements for the human facing aspects of the functionality may likewise change as the system becomes more familiar to the user. In this case, it is good practice to try and ensure flexibility within the interface design such that it is possible to highly tailor the operations of the human facing aspects of the system (for example see Figure: Guardian’s Adaptive Website). This flexibility, however, leads to increased complexity within the design and likewise an increased pressure is placed on time and cost. If flexibility cannot be easily achieved in a cost-effective or-time effective manner, then it may be more appropriate for a series of software hooks to be left in the underlying design is such that changes can be made and the system can be modified if required at a later date.

One key aspect of flexibility is the ability to adapt your system on the fly, based on a device description, or to build in the ability to conform to different devices. Remember we talked about ‘Model View Controller Architectures’ way back, well this separation of concerns enables real-world frameworks, such as Nokia’s Qt – in the development cycle, the separation of concerns facilitates flexibility of the interface and, therefore, enables adaption to a target device (for example see Figure: Qt Development).

Questions to think about as you design your prototype:

- Does your system allow users to conform the colour encoding to their preferences?

- Can the user personalise the interaction settings, and change the length of any timed events?

- Can the user personalise the interface settings, including different styles and sizes of typography, fore and background colours, and default interface look and feel?

- Can the keyboard be remapped?

- Do you allow keyboard shortcuts and accelerator keys to be personalised to the user preferences?

Remember… these are just the first five of our total principles - for the next batch you can skip ahead. But just because you can, maybe you shouldn’t… take your time to read the rest!

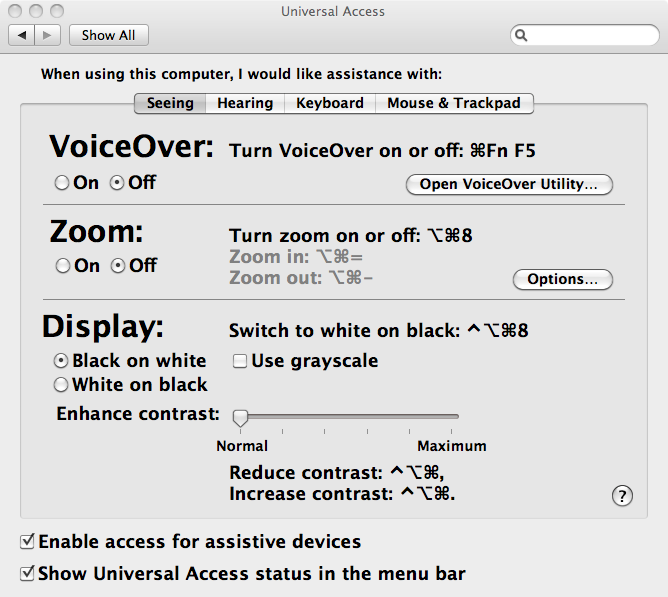

Now I’m presuming you aren’t building an operating system from scratch but are getting one out of the box. In this case, lots of stuff is already done for you (for example see Figure: OSX Accessibility Settings), so I’ve not listed it in the questions attached to each principle – that are all still valid anyhow. Now if you are creating one from scratch, maybe for a bespoke kiosk, auditory driver feedback system in a car, for an embedded system - you must also think about input and output of the OS via the hardware and devices attached to it. How will you set key-repeat intervals for people with tremors, how will you notify hearing impaired users if there is only auditory feedback? There are many more questions to be thought about, and so you should make sure your system is compatible with a modern accessibility bridge, provide ports for Bespoke I/O hardware, and take an in-depth look at ISO 9241-171:2008. What’s more, you’ll find that in some accessibility guidelines, robustness which I cover later – is often included; however I think of this as either part of the ‘utility’ / engineering of the system or as part of its efficient use15.

10.5 Summary

Ask any well-informed developer to rate how important accessibility is, and I’d expect most to rank it high. Ask them why, and I’d expect most to talk about disabled users, altruism, and the law. An enlightened few may talk about the business case, or expand on the many technical advantages of making their software accessible.

It may surprise many designers and developers to know that when they are developing accessible code they are also, more than likely, developing aesthetically pleasing code too. But this shouldn’t be the most basic motivator for accessibility. Indeed, developers should also understand that accessible means mobile.

Designing and building effective systems aren’t just about accessibility, but by being accessible, we can ensure effectual usage. Indeed, accessibility is now not just about making systems accessible to disabled users, but based on the belief that we are all handicapped in some way by the environment or the devices we use. We can see this in our earlier discussions on situational impairment, and in some cases, people have begun to refer to temporal impairment or temporary impairment that is our inability to use effectively our computational systems for short amounts of time-based on some characteristic of ourselves or the environment or the condition of both.

Understanding that interfaces must be transformable also supports users who are conventionally excluded. Currently, the opportunities created by computer technologies are not enjoyed by the whole of society. Indeed, there is a strong correlation between technological exclusion and social exclusion. There are significant and untapped opportunities to use technology better and on behalf of citizens, communities, and digitally disenfranchised groups. However to achieve inclusion, systems must be created seeing the user experience, not as an adjunct, but as a part of an integrated solution from the outset. We know that the multiplicity and ubiquity of devices and their interfaces are key to successful inclusion, households may very well have a games console or digital television, but no general purpose computer system. Being able to deliver content to any device, and support the users needs as opposed to the developers is key to making good interfaces that will be used, and which matter to real people.

Effective use is not just about disability, if anything it is more about a flexibility of mind at every level of the construction process from commissioning, through design and build, and on to evaluation. Effectual use accentuates good design and adaptability which helps future-proof your builds against changes in technologies, standards, and extensions to the design.

I cannot impress on you enough my belief that by understanding disabled user’s interaction we can gain an understanding of all users operating in constrained modalities where the user is handicapped by both environment and technology. UX testing and audit including users with disabilities is a natural preface to wider human facing testing focused on effective use.

10.5.1 Optional Further Reading / Resources

- [M. Burke] How I use technology as a blind person! - Molly Burke (CC). YouTube. (2015, December 18). Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch…

- [W. Chisholm.] Universal design for Web applications. O’Reilly Media Inc., Sebastopol, CA, 2008.

- [A. Kirkpatrick] R. Rutter, C. Heilmann, J. Thatcher, and C. Waddell. Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance. Friends of ED, July 2006.

- [S. Harper and Y. Yesilada] Web Accessibility: A Foundation for Research, Volume 1 of Human-Computer Interaction Series. Springer, London, 1st edition, September 2008.

- [Y. Yesilada and S. Harper] Web Accessibility: A Foundation for Research, volume 2 of Human-Computer Interaction Series. Springer, London, 2nd edition, 2019.

10.5.2 International Standards

- [ISO 9241-171:2008.] Ergonomics of human-system interaction – part 171: Guidance on software accessibility. TC/SC: TC 159/SC 4 ICS: 13.180 / Stage: 90.20 (2011-07-15), International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- [ISO 9241-20:2008.] Ergonomics of human-system interaction – part 20: Accessibility guidelines for information/communication technology (ict) equipment and service. TC/SC: TC 159/SC 4 ICS: 35.180; 13.180 / Stage: 90.60 (2011-06-17), International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- [ISO 9241-129:2010.] Ergonomics of human-system interaction – part 129: Guidance on software individualisation. TC/SC: TC 159/SC 4 ICS: 35.180; 13.180 / Stage: 60.60 (2010-11-08), International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- [WHA 54.21] International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) - http://www.who.int/lassifications/icf/en/ .

- [UN ESCAP] UN ESCAP Training Manual on Disability Statistics - 2.3 ICF terminology and definitions of disability http://www.unescap.org/stat/disability/manual/Chapter2-Disability-Statistics.asp#2_3 .