Part III: Building the User Experience

8. Developing for UX

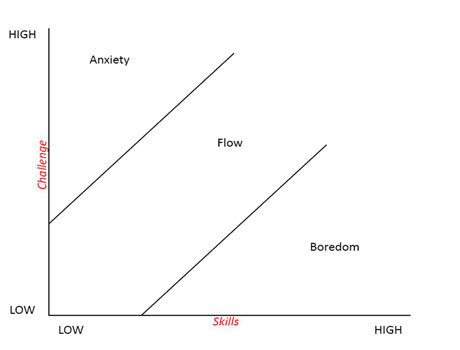

Happy developers are productive developers; productive developers produce beautiful code as well as beautiful interfaces.

– Anon.

User Experience is an umbrella term used to describe all the factors that contribute to the quality of experience a person has when interacting with a specific technical artefact, or system. It focuses on the practice of requirements gathering and specification, design, creation, and testing, integrating best practice, heuristics, and ‘prior-art’ whereby the outcomes can be qualitatively evaluated using small numbers of users, placing humans firmly in the loop.

In my opinion, the user experience process starts with the ‘User Experience Engineer’ as end-user. By this I mean that the user experience of the UX engineer is often ignored; as is the user experience of software engineers who may also assist in the creation of the artefact. But it is critical not to miss out aspects of the software engineering process. Start with the right tools that fit both the development and the developer. This rationale extends to the methodology/lifecycle used, and the ethos of the development in general [Martin, 2011; 9241-100:2011, 2011].

8.1 UX Development

User Experience departments look different in different organisations and corporations. In some, the UX engineer is responsible mainly for the interactions with the users before the development begins. Also in the requirements gathering phase, and after the development is ‘finished’, in the testing and evaluation stage. However, in some departments the separation may be more flexible, and you may also be tasked with building parts (or mock-ups) of the interface and interactivity yourself.

If you are lucky, you may be part of a ‘Skunkworks’ team or an organisational research department. Where you will be part of a small and loosely structured group of people who research and develop a project primarily for the sake of novel innovation1. The skills-set you will be required to use in each of these situations are different. However, your training should allow you to undertake any2.

Of these three scenarios, the one that requires the most careful navigation and communication is the first. Here you are responsible just for the human facing aspects of the work and are seen as the liaison between the users and the software engineers. This requires good communication skills and the ability to understand complex technical issues while translating these to more simple concepts for user dissemination.

In this scenario, where you are not allowed to develop the software yourself, it is difficult to overstate the importance of the general software engineers. Those who are building the system functionality and by implication, your interface and interactivity. If these technical staff are not ‘on your side’, then your project is likely to fail. The difference between a good software engineering and bad software engineering is critical. Even more critical for a good user experience we would expect much of the complexity of the interface to be removed to the underlying software functionality. Or generate underlying software functionality to enable a more complete and interesting user interaction.

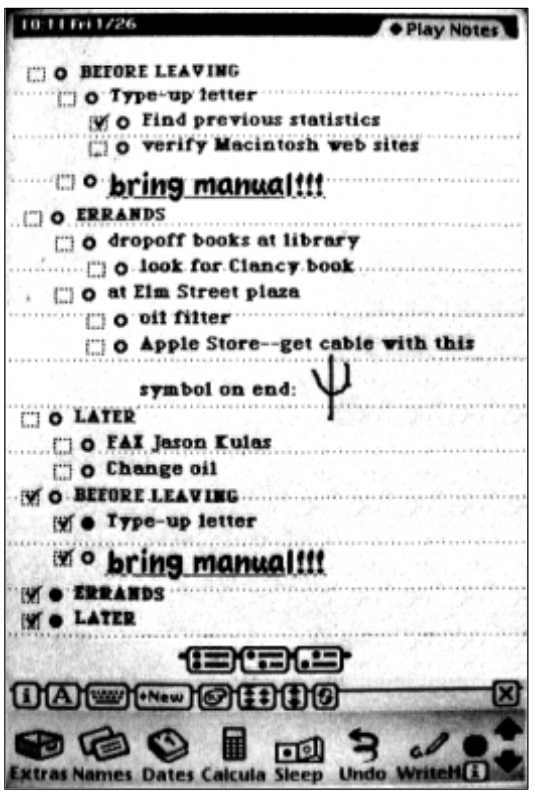

Let me illustrate with an example, in this case, the development of the Apple Newton in the early 1990s. This system was widely seen at the time as having an excellent interface (see Figure: Apple Newton UI). But the main reason this interface was so powerful was because all applications could share data between them. This meant that writing a name in your calendar would automatically link to that name in your contacts list and bring through relevant information on addresses and telephone numbers etc. into the calendar application. This was possible because of the farsightedness of the underlying software engineering in which data was stored as ‘soups’. Soups are a very simple flat database in which the specification of the data is stored with that data. In this case, all applications can delve into the different soups created by different applications, using their data at will; termed ‘cross soup compatibility’. Without this underlying, but often invisible, mechanism the user experience would have been much reduced.

The point I’m trying to make is that the underlying functionality is as much a part of the user experience as the interface (either virtual or physical) itself. The software engineer can bring this level of innovation to a UX project, but this takes good communication, good involvement, and often the opportunity for the engineer to build elegance3 into the code base [Oram and Wilson, 2007].

Finally, it is not my intention to describe the kinds of tools a developer should use, these are often personal choices or defined by the organisation in which they work. A developer’s choice of tool often makes more sense to the developer than to anyone else. Indeed, I have witnessed many arguments between developers as to the relative benefits of code generation using; say, the Eclipse Framework as opposed to NetBeans (see Figure: Netbeans Debugger), or vice-versa.

What is more important is the development methodology and the development ethos which should support the kind of interactions and feedback naturally provided by users.

8.2 Development Methodologies and Lifecycles

It is often the case that the UX engineer will need to fit into the design methodology and lifecycle that has been created by the project managers. In this case, there is little one can do to alter or modify this decision and all that remains is to understand the advantages and disadvantages of that lifecycle within the context of the UX work. Indeed, the decision as to the methodology and lifecycle chosen is often very personal and may also be based on the experience of the project manager’s previous successful use of that methodology. It may also rest on the desires of the organisation and the needs that they may have concerning maintenance and dissemination within the organisation at a later stage.

In this case, there are a number of models of the development lifecycle accompanied by a number of engineering methodologies that conform to aspects of these models [Sommerville, 2011]. But, these are often more specific about the tools and techniques that are used in the different stages of the underlying model than we may like. I do not suggest that the following descriptions are in any way exhaustive. They should give you an initial understanding of the types of development that are often undertaken. As well as an overview of some of the most popular methodologies that are used in common software engineering practice. Let us start with the four most common models currently in use.

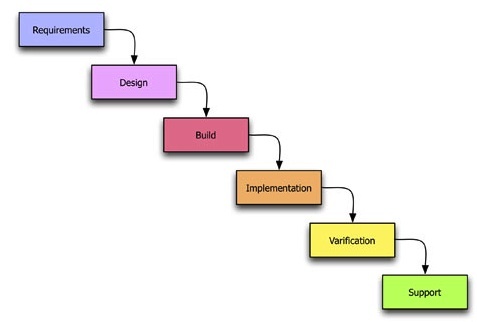

8.2.1 Waterfall

The worldview of the waterfall model is that each aspect of the development lifecycle occurs in a tight and rigidly strict order. Here which each phase must be fully completed before the next can begin (see Figure: Waterfall Methodology). In this case, imagine a series of phases starting from the top left and descended diagonally to the bottom right. Normally we would start in the top left with requirements and finish in the bottom right with maintenance. Usually, there are phases of design, implementation, and verification that make up the remainder of the waterfall development lifecycle. However, these can vary and be extended based on the specific kind of waterfall model that is being used.

In this way requirements inform design, design informs implementation, implementation informs verification, and finally, verification informs maintenance. In some cases, there is a feedback that runs from the last phase such as maintenance or verification directly up to requirements. This is used to show that there is some cyclical behaviour between the elements of the waterfall model. In my personal opinion, this is the worst way of doing human factors work because each part of the human-centric development is confined to each specific lifecycle phase. This means that it is very difficult to feedback and change the requirements of the human facing aspects of the project to fulfil the user needs and their changing requirements. Or indeed redesign to remove any development miss-perceptions of those user requirements. In reality, it is my opinion that the waterfall model is far more suited to rigid software engineering. Whereby the key focus is accomplishing the project plan such that the contract between the commissioner and the developers is filled on time and to budget. The user requirements are only valuable in that they are met as part of the formal development specification regardless of their applicability to the end user. It is my opinion then that the waterfall model is far more targeted to contractual fulfilment than system usability. I would also suggest it is very difficult to ad-hoc modify the waterfall methodology to suit the requirements of the user experience ‘process’ - try not to use this model if at all possible. If you have no choice, try to iterate requirements and design as much as your organisation will allow - and suggest from the outset that they link verification to implementation; it will be a tough sell!

8.2.2 Spiral

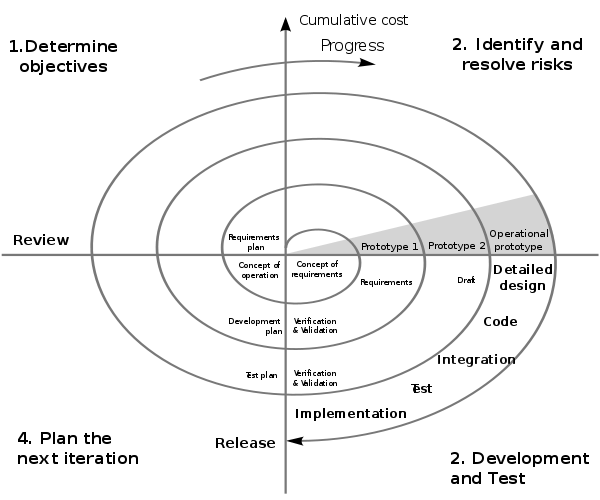

The spiral model is different to the waterfall model in that it splits up each task into some tasks that are iteratively undertaken. In this way, the worldview of the spiral model is that each aspect of the development lifecycle requires multiple iterations before proceeding to the next phase. Each phase requires the determination of objectives, the identification and resolution of risks, development and testing, and finally planning for the next iteration. The spiral model is named because the development track can be drawn as a spiral emanating from a central point. To visualise this, imagine that a piece of paper is divided into quarters with a central point being the start of the development lifecycle (see Figure: Spiral Methodology). The spiral tracks through each quarter starting from the top left in a clockwise manner represent each of the four stages of the iteration phase (objectives, risks, development, plan).

As the development tracks spirals out it is annotated with the larger aspects of the development lifecycle. These are aspects that will be required at the time such as requirements, design, development, validation and testing, and maintenance, similar to the waterfall model. However, the iterations are tighter at the centre when designers are gathering the requirements and designing the system and become longer as they spiral out towards the edge where we arrive at detailed design coding and implementation. In the context of UX development, this is a better model than the waterfall model described previously. This is mainly because it acknowledges that some iterations will be required for each of the phases. And it also acknowledges that these phases may need to be redeveloped based on new information uncovered in different parts of the evolving development. Not perfect for the UX process but acceptable without much ad-hoc modification!

8.2.3 Iterative

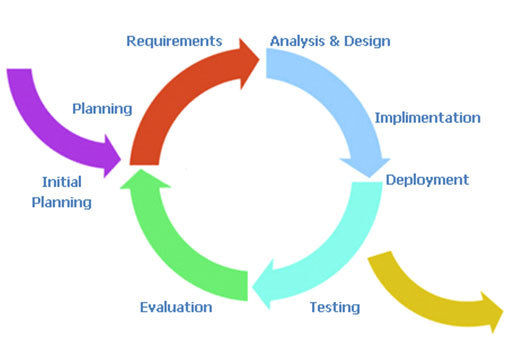

The worldview of the iterative model is different than the waterfall or the spiral models. This is because it sees software development as a circular process comprising requirements, analysis and design, implementation, testing, evaluation, and then planning for the next iteration. This means that it sees the software engineering lifecycle as iterative and cyclical as opposed to a rigid sequence of phases that have no impact on each other once the development is underway (see Figure: Iterative Methodology).

The iterative system is very easy to understand. All the user needs to do is imagine a circular process running in a clockwise direction with each of the main phases of the development equally spaced. An initial planning phase feeds into the initial entry point before the requirements elicitation is undertaken, and an exit point is available after implementation and signifies deployment. In reality, the deployment exit could be linked to the initial planning entrance to signify the continual maintenance the system will undergo. For UX development, this is my second most favourite model because it takes into account the impact that the user testing will have on the next iteration of development and planning. It supports the view that, from a user perspective, we cannot understand all aspects of the user experience before some development, even prototypical development, has been undertaken. In this case software that is far more suited to the user is created and modifications can be made to refine the design on subsequent iterations. The major drawback of the iterative approach is that the endpoint can sometimes become lost in the focus on an ever more refined software artefact. In this case, the software development manager must make sure that they have some understanding of the number of iterations they expect to occur for any specific development. Making sure to plan time for an extra one or two iterations to account for unforeseen circumstances. A good choice for the UX process which can progress without ad-hoc modifications.

The two key models that have been left out of this general discussion is the Agile Method and Cowboy Coding. This is because these are my two preferred methods for user-facing development. I want to talk about them in more detail later and within the context of research and development in the human factors domain.

In addition to these three overarching models of the software development lifecycle, there are a number of well-known methodologies. These make specific recommendations as to the kind of practical processes, tools, and techniques used for requirements gathering, design, and development. Five of the most common are covered in more detail next.

8.2.4 Structured Systems Analysis and Design Method

SSADM is the first methodology I learned when initially training to become a software engineer. It is based on the waterfall model however it has one notable difference, being that there is far more time devoted to the initial requirements engineering process. Indeed, in the standard design there is a feasibility study, an investigation of the current environment, an understanding of the business organisation and systems, and finally a requirement specification phase. This means that the system is very top-heavy when it comes to modelling the user. In most cases, this is a good way of understanding the context of the development as well as the real system aspects that are required by the organisation commissioning that development. Although in some cases, commissioning organisations start to become uneasy at the amount of time which elapses between starting a project and seeing some tangible technical developments. But, if you have no choice but to use a waterfall type model then SSADM would be the one I would think of first because of its heavy user involvement from the start.

8.2.5 Rational Unified Process

RUP is a methodology that you will probably encounter at some point in your career because it is so commonly used. The Rational software company, who originated this process, were bought by IBM and so the tools and techniques to support this process have been created because it is IBM’s preferred development method. One of the main advantages of RUP is the fact that the process is flexible, in this way it can be tailored and modified to suit the development being undertaken with various aspects being included or left out. In general, there are four phases in the lifecycle being the: inception, elaboration, construction, and transition phases. The only real phase to discuss in more detail is the transition phase the others being reasonably similar across all methodologies. In reality, the transition phase is about deployment and the move from the development into a production setting; making it available and understood by the end user. While RUP is based on an iterative lifecycle, its support for the user-facing aspects of the system is less well-defined than those dealing with project management and software creation. If I had a choice, I would not use RUP directly but would look for an agile variant such as the Agile Unified Process.

8.2.6 Scrum

Scrum is again an agile and iterative methodology that is focused on managing the software development lifecycle in a rapid iterative fashion. Scrum development has two types of roles, the pigs, are the people who are performing the software development process, and the chickens, who are the people for which the development is being created. Understanding that chickens are a first-class citizen within the development cycle is very encouraging for the UX engineer. Scrum accomplishes its iterative releases using sprint’s which are broken down into 30 days or 24-hour cycles. Projects are initially broken down into things that need to be accomplished. There is then a plan developed for how these things are to be created. A sprint occurs such that an entire ‘plan of accomplishment’ can be realised as an incremental development after a 30-day period. In this way, chunks of the system are created piece-by-piece as opposed to a more waterfall like separation of concerns in which the cycle is longer because the project resources are divided into different development teams. This is a useful way to go about UX development because it enables aspects of the software to be released to the user in a fast incremental manner. Indeed, use and testing can already start before the software is near completion. Therefore, changes requested by the chickens can be integrated by the pigs in the next sprint.

8.2.7 Rapid Application Development

RAD can be thought of in two contexts, the first being as a model and the second being a methodology. In the case of UX work, I favour thinking of it more as a methodology than as a model. In reality, there are many forms of RAD but the main factor that differentiate it for UX work are that it uses minimal planning. RAD is far more about rapid software prototyping with high user input than it is a fixed and delineated software development cycle. In this case rapidly created models of the software are tested with users before the main functionality and interaction design are fixed. In this way, the user has a high input into the system. Once the system is created, there is an implicit knowledge of how it will work and what it will look like, along with the functionality it includes.

8.2.8 eXtreme Programming

XP is one kind of rapid application development which requires developers to work in pairs without a detailed design. The lifecycle is cyclical and involves frequent small (point) releases of the software for consumption by the users. XP asserts that by programming together as a pair more can be achieved than by working alone. And that by frequent releases the users will always be kept involved in the lifecycle as opposed to at a distance. This means that user comments can be accommodated very quickly and that the views of users are taken into account as the implementation proceeds. In reality, this means that the users end up with a finished piece of software which by halfway, or three-quarters of the way, through the project has attained a level of stability. Therefore, additional modifications may not be immediately perceptible to the end user. In this way, the lifecycle minimises the ability to miss undocumented user requirements within the specifications. It also enables changes or errors to be addressed immediately and removes the tendency for users and user testing to be seen as an afterthought to a contractual deadline.

In addition to these methodologies, I can think of at least another twenty which you may come across. However, the five listed above represent the general dichotomy of methodologies and management practices that you should minimally be aware of. SSADN is well-known, mature, and contractually safe. RUP allows flexibility and has a number of tools to aid the development process, however, in using these tools you will be conforming IBMs specific view of the method. Scrum places the user as a first-class citizen, is often used in open source software development, but has a lower uptake in the commercial sector. RAD is characterised by its lack of design and heavy reliance on incremental prototype development which is often seen as suboptimal in the business view of a development lifecycle. Finally, XP adds structure to rapid, agile methods but is intensive and hungry for user time in the development cycle.

8.3 Methodologies More Suited to the UX Process

I find that the more development I do the more I come back to two very different kinds of methodologies for two very different kinds of UX work. In a way these methodologies are very specific to the way I normally do things and in this case you may disagree and have your own preferences. However, I would suggest that when you do not know what you need in the development. Or that the development is purely focused on research, and therefore very little is predictable or known from the outset, Cowboy coding is the only real tangible method of getting started. Once you can begin to predict different aspects of the code development with specific requirements for the software processes cowboy coding is no longer appropriate. Then agile methods become a far more favourable way of creating software that dovetails into business processes and enables a specific timeline to be followed. Indeed, you may wish to use cowboy coding if you are incubating ideas and designs, moving to agile process when you start to align your prototypes with the business requirements of the development.

8.3.1 Don’t Know What You Need… Cowboy Coding

Cowboy coding is used to describe software development whereby the developers have autonomy over the process. There is no project plan or direct timelines, and the schedule, development style, and algorithms are all decided by the individual developer or the development team for the specific project. In the case of research development, it is often very difficult to understand the problems that will be encountered; or a timeline for the solution to be developed. In this case, it is inadvisable to conform to a specific fixed lifecycle methodology because understanding what will be required and how long that will take to develop is not possible. Indeed in some cases the experimental outcome of the research is not a fully working system. Rather, a better understanding of the things that can be done and the things that can’t be done; you find this method in use in many skunkworks or R&D labs.

This is a key difference to the standard commercial view of software development. Here most of the problems will be soluble because many aspects of the system have already been created and are well understood. It is merely a matter of automation that is required. This is not to say that the development process is not a difficult or taxing one, and we can see that there are many examples of this process failing. Indeed, the reason we have so many lifecycle designs is specifically because projects often fail. However these are very separate, and different, concerns than that of research coding. This is because research coding expects the challenges to be so significantly difficult that the research developer will need to rapidly change their algorithms and processes. Complete and whole systems are often not required with just aspects of the software development being tested. Research software does not have to be tested to the same level as commercial developments, and positive project outcomes are still possible even if the software system is not developed in its entirety.

It is for these reasons that cowboy coding is more practical. The development must commence without wasting time on project planning that will - in the end - serve no purpose. In some ways, the research developer expects their development to not ever reach deployment maturity, or that the problems inherent in good research should be so insoluble that a complete development will never really be possible. Cowboy coding is useful for experimental and skunkworks work because the coding team is often one person or a very tight and focused team. In this way, it is difficult to see how maintaining a large and unwieldy methodology, with the added administrative overheads would be in any way useful. This is not the case for commercial developments or developments that are moving out of the prototypical phase, in which a more rigorous methodology is required.

8.3.2 Know What You Need… Agile Development4

The Original Manifesto Signatories are: Kent Beck, Mike Beedle, Arie van Bennekum, Alistair Cockburn, Ward Cunningham, Martin Fowler, James Grenning, Jim Highsmith, Andrew Hunt, Ron Jeffries, Jon Kern, Brian Marick, Robert C. Martin, Stephen J. Mellor, Ken Schwaber, Jeff Sutherland, and Dave Thomas.

It is often easy for the UX’er to remain at a distance from the development lifecycle. This is especially the case where they are from a psychology background as opposed to a computer science - or software engineering - background. Many different opinions exist as to the ‘best’ methodology to use for developing commercial software. However, it is my contention that agile methods are far more useful and flexible concerning the human facing aspects of the development than the others described above. This being the case you should realise that this section on agile methods is my very personal view on performing practical UX work within the context of a larger software development.

“In February 2001, 17 software developers met at the Snowbird, Utah resort, to discuss lightweight development methods. They published the Manifesto for Agile Software Development to define the approach now known as agile software development. Some of the manifesto’s authors formed the Agile Alliance5, a nonprofit organisation that promotes software development according to the manifesto’s principles.”

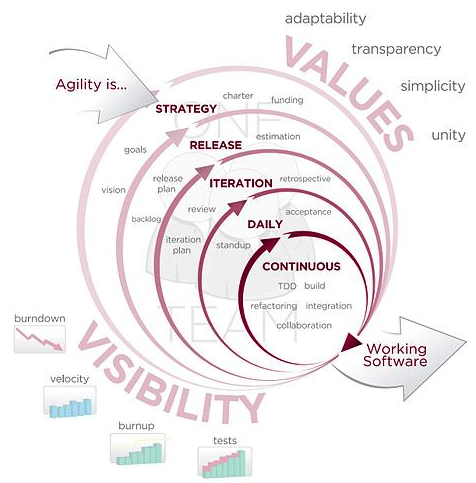

Agile software development [Cockburn, 2002] is based on iterative methodologies where requirements and solutions evolve through collaboration. The teams that implement these solutions are often self-organising and cross-disciplinary or interdisciplinary in nature. Development is not free-form however, and there is still a development lifecycle and project planning effort which accompanies agile development (see Figure: Agile Methodology). However, the time between cycles is often very short such that software can be delivered at weekly or monthly intervals. And indeed time periods within the model are often measured in weeks rather than months or quarters; the work being performed in a highly collaborative manner.

The Agile Manifesto6 aims to ‘uncover better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it’ and has four main values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools;

- Working software over comprehensive documentation;

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation; and

- Responding to change over following a plan.

Stating that ‘while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more’.

We can see that the agile method’s lifecycle is highly tailored towards the individual user and keeps these users within the system, being integral parts of the deployment process from start to finish. It is for this reason that agile methods represent, in my opinion at least, the best development lifecycle and methodology for human facing developments. By understanding that the user is placed above contracts and project timelines we can be sure that the final version of the software, which in some cases will be used for many years, fulfils the users needs and through its maintenance cycles fulfils their future needs too.

In addition, there are 12 practical principles behind the Manifesto:

- Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software;

- Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage;

- Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale;

- Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project;

- Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done;

- The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation;

- Working software is the primary measure of progress;

- Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely;

- Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility;

- Simplicity—the art of maximising the amount of work not done—is essential;

- The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organising teams; and

- At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, and then tunes and adjusts its behaviour accordingly.

As you will be aware from our previous discussions, there are different forms of agile development and these different forms can be useful in different contexts. There are no de-facto winners when it comes to these methods because the context and the desired user outcomes are different for each specific agile method. In this case, you may decide to choose XP, RAD, or any of the other methods listed above, or indeed those created after this text was written. In any case, the focus should always be that the individual and their interaction requirements should be considered before the needs of the development team.

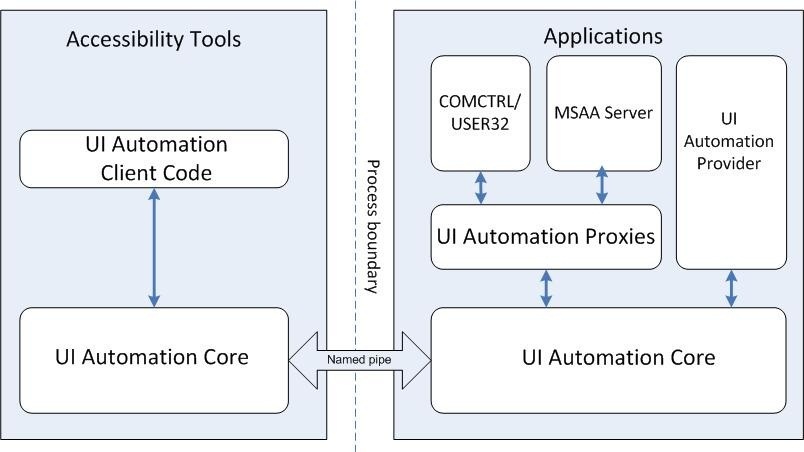

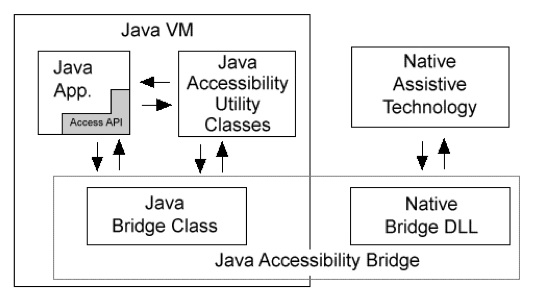

8.4 Separation of Concerns

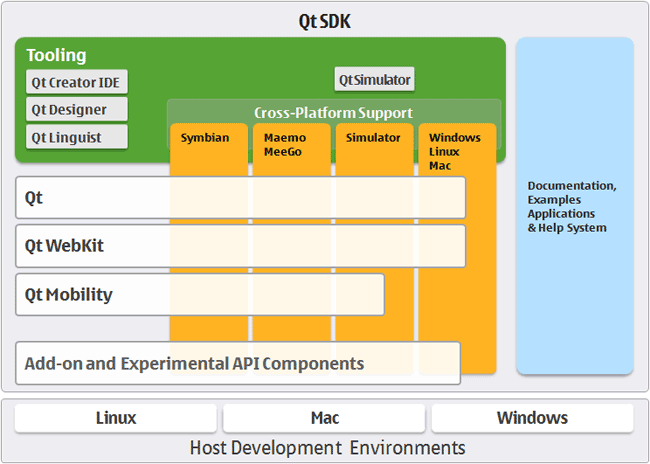

The separation of concerns is a key aspect of software engineering practice in which each logical part of the system is dissected and separated as much as possible from the other parts of the system. The interactions between the system components are well specified and take place through well-defined interfaces. By separating system concerns it is possible for the development of each part of a complex system to be undertaken in relative isolation from the other parts. Complexity often occurs in systems because of the combinatorial nature of the tasks required to be undertaken. By decomposing those tasks and separating them into isolated components, complexity — or the possibility of increased combinatorial complexity — is reduced. This means that developments can occur in parallel, and it also means that complex aspects of the system can be more easily handled. An example of a real-world development system that makes use of these separations is Nokia’s Qt Framework (see Figure: Nokia’s Qt Framework).

For the UX engineer, separating the presentational concerns from the other logical components of the system has a high degree of utility. This is because the interface and the tasks that surround it can then be created in isolation from the other components of the system, only calling on deeper program logic through predefined and well-understood interfaces. Therefore, the interface dialogue components and human aspects of the system can be developed and tested in an agile development cycle until the human-centric parts have been fully tested and evaluated. Finally, the underlying logic can be linked and so the development - even using the Waterfall Methodology - can proceed with the knowledge that the interface components are fit for purpose.

Following this ethos also enables automatic generation of certain aspects of the system. This means that different presentational components can be generated by combining a model of the functional tasks that are required to be undertaken along with a model of the user requirements. In this way, either model can be changed without requiring each presentational aspect to be altered. Small model changes percolate through to the real-world practical deployment without necessitating full systems redevelopments.

Many different systems have evolved out of this desire to separate concerns and to generate aspects of the system automatically for both different platforms and different user types. While the following are not an exhaustive list, they give the reader a general idea of why and how these techniques can be so powerful.

8.4.1 Model View Controller Architecture

The MVC architecture suggests a reasonably simple separation of concerns which isolates aspects of the user input (control), from aspects of the user interface (view), from the underlying description of the programming application logic (model). This means that input is handled by the controller that passes on that input to the model. The model handles this input and updates the underlying data structures and associated output accordingly. Finally, the view queries the model such that changes that have occurred, based on the most recent input in combination with the state of the model before the input, are related back to the user via the interface. Some implementations of the MVC architecture also create a dependency graph that enables only aspects that have changed to be updated through the view. The most complex aspect of this architecture is the model because it handles moving between specifically defined states. This is based on the user input and the previous state of the model. State transition diagrams can be very useful within this context. The view itself is the main focus for the UX engineer. And by abdicating much of the responsibility of the input, event detection, and changes within the model state to other concerned parties within the system, the focus can remain firmly on enhancing user interaction. At the minimum making sure that user’s interaction is not hindered by a badly built interface. Also by correctly modelling a view, many different interaction requirements can be supported without the need to individually code each one.

The Model View Presenter (MVP) architecture is a variation upon the MVC architecture in which the model is the interface defining the data to be displayed or otherwise acted upon. The view displays the data while the presenter acts to both retrieve and format data. There is no consistency between implementations of this architecture and the degree of logic permitted within each view varies. However, all implementations have the aim of facilitating automated unit testing and improve the separation of concerns in the presentation logic.

Finally, the Presentation Abstraction Control (PAC) architecture is similar to the MVC architecture however it occurs in layers. Each layer contains a number of so-called agents, and the agent comprises presentation, abstraction, and control elements. These agents only communicate with each other through the control element and in this way each agent completely isolates both the presentation and abstraction elements. This means that presentation components can be further disconnected from each other with their underlying program logic housed within the same agent. This has some benefits in the UX domain however it also means that additional communication via the control element needs to be undertaken, and consistent abstraction across layers and agents must also be present.

8.4.2 Multilayered Architecture

Multilayered architecture breaks each aspect of the system into a separate layer running from the user interface layer at the top, through the application layer, through the domain layer, finally reaching the infrastructure layer. Indeed, it is this domain layer that the model view controller architecture uses as the model to drive the generation aspects of the system. Sometimes the domain and application layers are conjoined as there can often be some overlap between the description of the business rules within the domain and the actual application of those rules within the real software architecture. The infrastructure layer focuses on interactions with the underlying platform, and the services which that platform provides. In this way, the infrastructure layer can be used to enact network connections, memory handling, and all the other system elements you would expect to be present in a modern operating system or platform.

For the UX engineer, the most important aspect of this architecture is the division of the user interface from the other layers. By understanding the flow of data and control in this hierarchical manner, it is sometimes easier for developers to think about the interface creation in isolation. The use of layers is common within software engineering and so it is more in keeping with the thought processes that the developer is already familiar with. The separation of concerns can still be maintained in this model because as long as the application interfaces between the different layers are well defined, isolation between the components can still be maintained. In this way, the user interface layer can be changed to suit different user requirements without the need to redevelop the other layers, which are isolated from each other, and the interface layer. However, in this case, the ability to change the interface layer based on an abstract description of the presentation and user requirements of the system is difficult. This is because multilayered architectures are often not based on abstract models of the system that are enacted at runtime. But instead are created to facilitate enhanced development. This means that the machinery required to generate these dynamic adaptive interfaces is not present directly within the system.

8.4.3 Service Oriented Architecture

SOA is a network architecture that requires a high degree of loose coupling of the services provided and the operating systems on which they run. SOA separates the functionality of the application into distinct uses and isolates that functionality from the operating system. This means that an application running on a desktop can call and interact with different services orchestrating the user interaction and the interface aspects of the system separately from those which are used to enact the program functionality. Therefore, services can be called from different nodes on the network, and in the case of the World Wide Web, across servers such that in some cases the developers do not even need to create the application functionality directly.

This kind of architecture is obviously very powerful for the UX engineer. However, it also comes with the problem of the persistence of the services that are offered and their availability from the supplying organisations. Creating a SOA type architecture by orchestrating local services means that specific computer resources can be used for tasks that they are most suited to. Also, a form of parallelism can be accomplished because different services can run at the same time on different computational resources all orchestrated by a single user from a single application interface.

Therefore, SOA’s preserve the separation of concerns to a high degree, reduce the complexity of combinatorial functionality because services are isolated from each other and are often focused on providing a specific service. Orchestrating the services is the most complex task. However, by maintaining this degree of loose coupling the knock-on problems of testing and debugging can be mitigated against those which arise in a system with a high degree of coupling.

We can, therefore, see that there are many different architectures that could be used by the UX engineer. All have strengths and weaknesses: model-based approaches enable the interface to be directly generated, based on an updated version of the view, very easily although additional functionality and machinery are required for this generation. Layered approaches are very practical and in some ways describe the system as it is developed. However, the separation of concerns is not as high as model-based approaches, and so there is always the possibility of functionality drifted between the different layers. Finally, service-oriented architectures support a separation of concerns by a high degree of loose coupling, to such a degree that these architectures are mainly enacted over entire networks. However, their orchestration is complicated, and if the system developer does not have full control over those services, then their persistence and accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

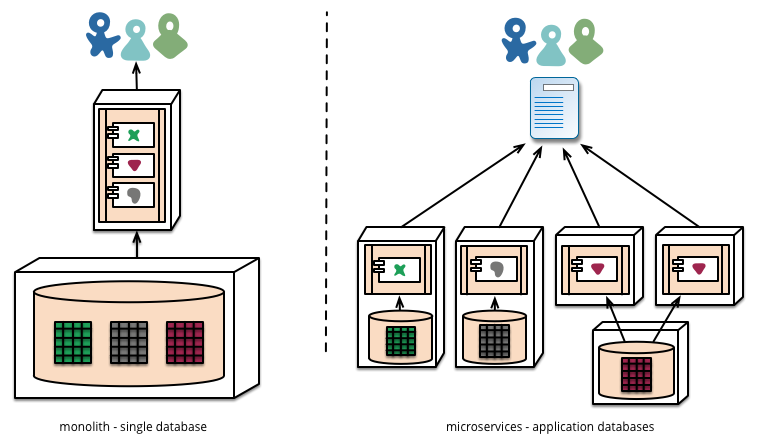

8.4.4 Microservices (and Devops)

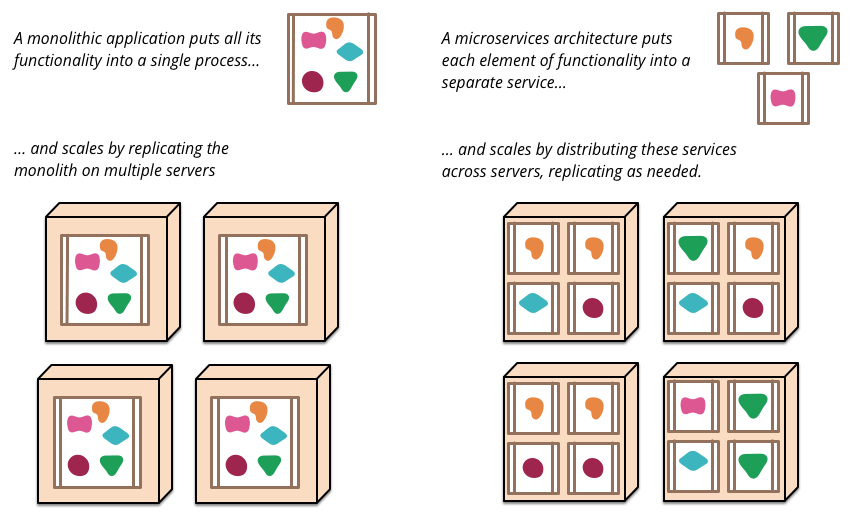

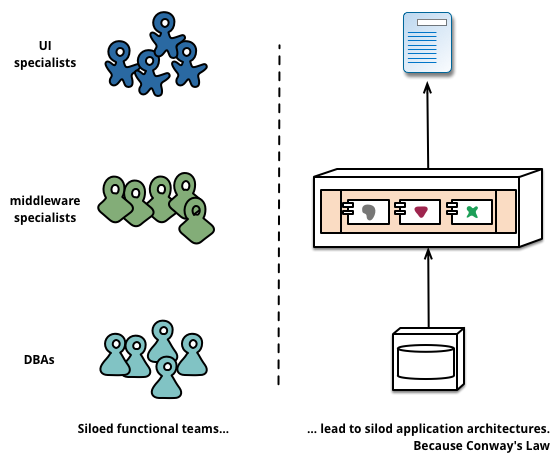

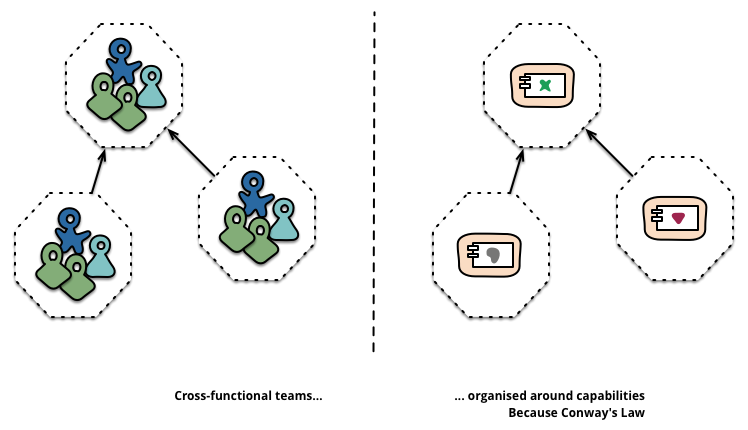

“The term “Microservice Architecture” has sprung up over the last few years to describe a particular way of designing software applications as suites of independently deployable services. While there is no precise definition of this architectural style, there are certain common characteristics around organization around business capability, automated deployment, intelligence in the endpoints, and decentralized control of languages and data.” – Martin Fowler

This is extracted from the best article on Microservices I’ve come across (even though written in 2014 at https://martinfowler.com/articles/microservices.html)

In short, the microservice architectural style is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API.

Microservices architectures are currently my preferred way of implementing UX based software. This is mainly because the ability for a piece of software to be created independently of other components and the communication cross facilitated at a later date enables us to separate our concerns not just in the context of development but also in the context of running the system.

As we know, maintenance represents around 70 to 80% of system development effort. And so, building a large monolith means that there are many unintended consequences associated with incorrect maintenance; updates which might very well take down a live system. In the past, this was not a big problem (!) because a release of new software would happen periodically on some sort of hard media and releases would occur infrequently. In this case, we could expect that extensive testing and debugging have been undertaken because the cost of a new release would be substantial. However, in the current climate of centralised systems, which are run over networks connecting to client application endpoints, then the separation of server and client means that systems would be normally expected to be always on. Further, agile’s focus on rapid iteration and deployment means that updates might occur very frequently, indeed up to every two weeks. And so systems which can be independently updated but are cooperating on a single purpose have a huge benefit for the robustness of the user experience.

So in reality what is a micro service? And how are they implemented? This is really a question for software engineering textbooks. However, in the context of user experience and the separation of concerns, we can think of a microservice as being a small component of a larger application but the management of data and interfaces are all controlled by that particular component for its specific job. Communication with other components typically occurs via a bus mechanism such that systems may not even be co-present on the same servers and different languages can be used as long as they all are able to communicate on the same bus. This means systems are very much more flexible in the way that they are developed and in the way that they are maintained.

There are, of course, downsides to microservices architectures, mainly in that they are slower to communicate, and if they are on different servers at distance this communication lag will be increased. However, with modern network and hardware technologies, these lags can appear almost imperceptible to a user at a client endpoint. Microservices architectures also lead us on to consider development operations or DevOps:

“DevOps is a set of practices that combines software development (Dev) and IT operations (Ops). It aims to shorten the systems development life cycle and provide continuous delivery with high software quality. DevOps is complementary with Agile software development; several DevOps aspects came from the Agile methodology.” – Wikipedia

DevOps acknowledges the increased need for maintenance of systems and also the agile nature of current development operations such that changes to running systems can be implemented with compartmentalised exposure to bugs and the removal of the possibility of a complete systems failure. Further, DevOps enables immediate feedback on user needs and requirements so supporting rapid agile development cycles. DevOps is beyond the scope of UX but putting users at the centre of all the systems, including those that are both running and being maintained is obviously a method of development, maintenance, and operations something that we should be supportive of.

8.5 Interface Frameworks and the GUI

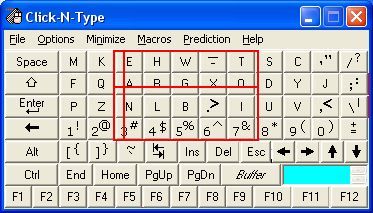

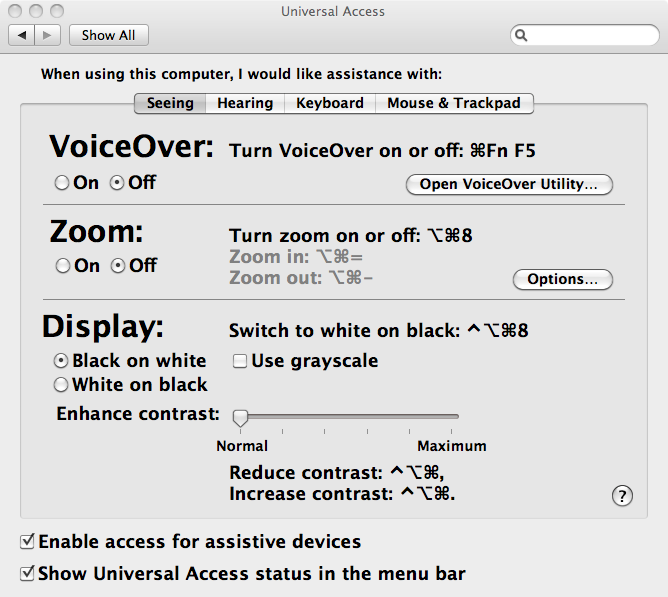

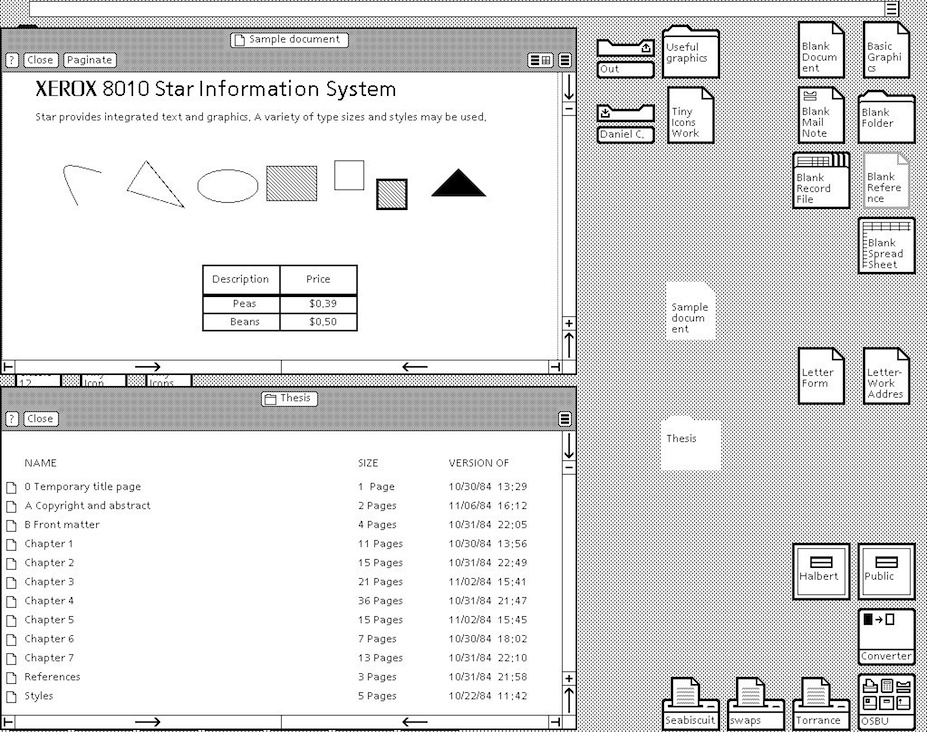

Graphical User Interfaces (GUI) are now the standard for user interfaces and will, therefore, be the most familiar to the user. There are other interfaces, such as the command-line interface, which also exist to enable user interaction with the system, however, these are often used by engineering subsections of the user community. The GUI is synonymous with the point and click operating modality of most interfaces today and use various real-world naming conventions to orientate users to different functionalities within the application domain. These GUI systems differ from earlier systems in that they make extensive use of the mouse to select the area of attention. Previously systems often worked on a menu based approach by which options are listed, and selections can occur via sequential keyboard operations. Point-and-click meant that different applications or modalities could be displayed at the same time, and the users’ attention would switch between these modalities based on their intent. Although managing the input and output of these GUIs tended to be complicated, non-standardised, and buggy. However, systems were developed to address these issues both at the operating system level and at the level of the application development.

8.5.1 Window Manager

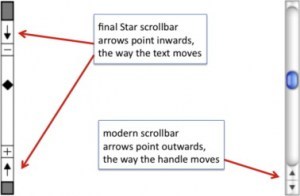

Windows manages derived from the WIMP concept that stands for window, icon, menu, and pointing device. These four aspects define the style of interaction that the user can expect within the windowing environment. The use of the pointing device in combination with the screen layout is intended to reduce the cognitive load. Thus enabling the user to remember both the actions which are available while at the same time reducing the learning overhead required to understand those actions and tasks. In this case, the windows manager is the generic name used to describe the operating system specific components which control the placement, appearance, and look and feel of the graphical user interface. The windows manager uses a set of real-world analogies that dovetail into the users’ cognitive understanding of what is being presented and tasks that will be required. In most cases the surface of the GUI is called the desktop, applications can be selected by clicking iconic representations or by following an iconic menuing system that allows easy selection of multiple applications at a systems level. This means that the user is not responsible for remembering all of the different applications on the system or how to execute them, but rather lists are presented such that a user can just double-click. Once an application has been initiated it runs in a window. The window analogy is used to reinforce the conceptual format of a view into a working application. Many windows can be open and running at any one time, and each window has a specific menu. Therefore, the commands that are required for each system do not need to be remembered. This list of commands is often found as part of the menu local to the application or in the now commonly known toolbar; that gives graphical representations of the functionality of the application. Few window managers are designed with a clear distinction between the windowing system and the window manager. Every graphical operating system that uses a windows metaphor has some form of window management, however in practice the elements of this functionality vary greatly. Operations usually associated with managers are those which allow the user to open, close, minimise, maximise, move, resize, and keep track of open windows. These facilities exist to provide a degree of consistency between application interfaces with menuing commands such as file, edit and help, etc. These are placed at the same location and following the same conventions across applications and platforms. Finally, most managers also come with additional facilities to help find and control windows and the applications which run on top of them, providing functionality such as docks; application launchers; task bars; and icons.

8.6 Windows Toolkits

Windows Toolkits were created to enable application interfaces to be programmed more swiftly by providing a component-based version of the common interface elements used inside the window manager. These toolkits provide off-the-shelf functionality which enables GUI elements to be speedily assembled and controlled, and also provide for keyboard and pointing interactions. Toolkits also assist development activity because they capture certain principles of interface design, including look and feel, for specific systems and remove the necessity for the developer to reinvent-the-wheel with every interface created. Components within these toolkits are often called widgets. This term is used to denote aspects of the toolkit such as menus, text boxes, scroll bars, spinners, etc. And so a Windows Toolkit can also be called a Widget Toolkit or in some cases a Gadget Toolkit. Another aspect defined within window toolkits is the ability to abstract away from the platform. And enable applications to be created for a specific toolkit (QT for instance) such that native code can be generated to enact that interface on many separate platforms. This cuts down the redevelopment requirements, which are often very heavy concerning interface development, necessary when porting a system from one operating system or platform to another. In many cases, the software engineer will develop code using cross-platform languages and so the application will often be platform neutral; only becoming native once it has been compiled on a specific operating system. However, the interface components often have to be re-implemented using the platforms proprietary Window Manager and toolkit. In this case, the software engineer can write for one multi-platform windowing toolkit that will compile for many platforms. There are problems with this approach, however, in some cases look and feel is not exactly matched to the underlying system and, therefore, the application is cognitively dissimilar to that expected by the user. As an UX engineer, you should only use abstract windowing toolkits if you can guarantee that the resulting native code will always conform to the look and feel of the underlying operating system or platform; as opposed to the specific toolkit itself. If this is not the case, you will end up sacrificing usability for ease of development. Is is an uneconomic model in the long run because the amount of user time will always be far greater than the amount of development time.

8.6.1 Skins

Finally, one of the most basic ways of changing the feel of an interface is to re-skin it. This means that the functionality and the structure of the interface remain unchanged, however, the visual theme and in some cases small aspects of the structure can be manipulated. These minor manipulations enabling users to change an applications look on-the-fly to suit their style of work or preference. Also, the ability to re-skin interfaces means that the application interface itself must be loosely coupled to enable the dynamic changes to occur. Skins may be also associated with themes. And the look and feel of the GUI, in general, can be changed such that these changes percolate through the entire interface including applications built with the native Window Toolkit. An application that is capable of having a skin applied is referred to as being skin-able, and the process of writing or applying such a skin is known as skinning. Some skins make the application more aesthetically pleasing while others can rearrange elements of the interface making the application easier to use. Allowing the interface to be re-skinned is more work for the developer that allows a certain level of personalization for the user, specifically the power user. Indeed in some regard, designing a system to be scalable means that changes in the interface, and personalization of the interface by the user, is supported and encouraged. This means that testing and evaluation with users is likely to show higher levels of satisfaction because the application can change to accommodate individual preferences.

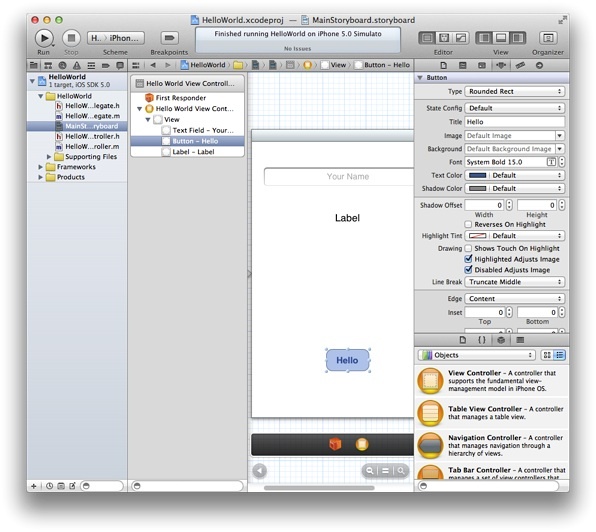

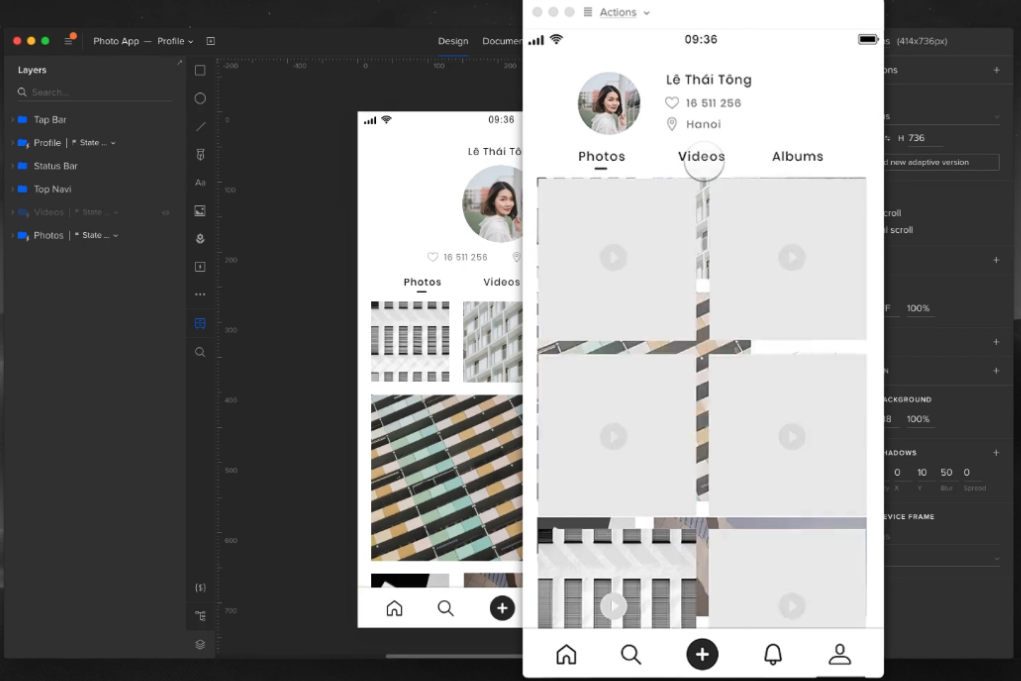

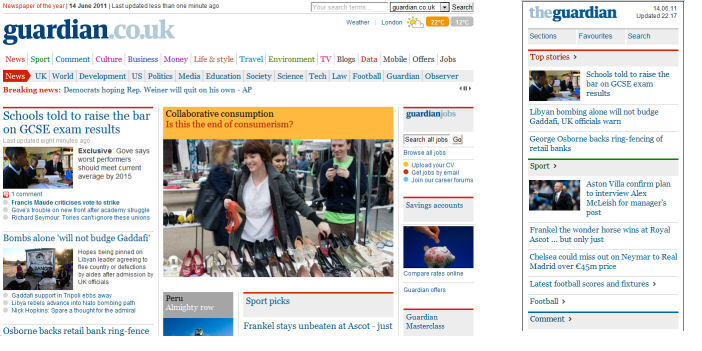

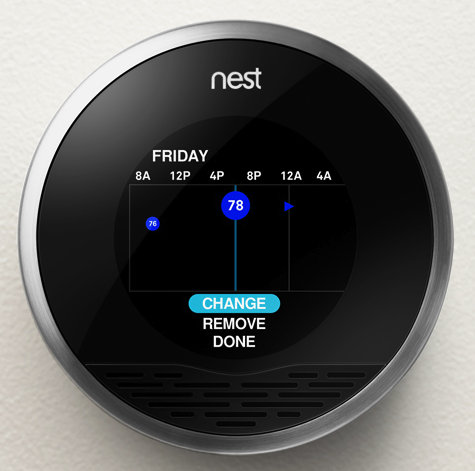

In reality, the interface design has previously been so difficult and non-standard that now the use of windowing toolkits, skins, and Windows managers have become all pervasive. Some argue that this has meant that the research and creativity of interface design have been affected such that different ways of interacting are not now pursued. In this case, you may be wondering why interaction and interface design are even a feature of this chapter. However, we can see that innovations do occur, especially when new devices force changes in the mode of user operations. For example the iPhone (see Figure: iOS Development) and the Android operating system have both changed interaction modalities such that gesture-based interfaces are now becoming more common. Concerning the standard desktop application, interaction design is focused on the placement of user interface components and the associated functionality of those components. So while the interface does not change directly, interface design is really about matching the needs of the underlying program logic with the best way to interact with that logic from a user perspective. Many interface components do the same job, but in different ways, it is, therefore, necessary to choose the most appropriate method and placement.

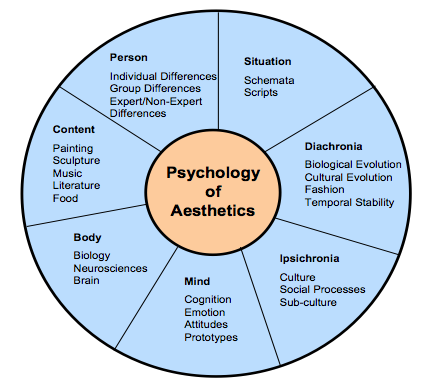

8.6.2 UXD and Visual Design

Let’s circle back to UXD and Visual Design. In short, we say that UX’ers of the technical/engineering type (you) should not get involved in visual design (although auditory design for conversational interfaces you are as well placed as anyone else). Follow the systems design language, use the development interface design guidelines, and where possible use pre-created toolkits to make sure you match look and feel. Consistency is very important at the interface level, and you should have a really good reason to break that look and feel.

8.7 Summary

This chapter has mainly dealt with enabling the UX engineer to understand the different kinds of development concerns and methodologies that may be applied to a user-centric development within the context of the software engineering process. Having the effect of making an understanding of the timescale, needs, and concerns of the software engineers more self-evident. And should enable the UX’er to become a better team player with the other disciplines that make up the development team.

As Eric S Raymond suggests in ‘The cathedral and the bazaar’ [Raymond, 2001] - and elaborates on in ‘Homesteading the Noosphere’:

“Anyone who watches the busy, tremendously productive world of Internet open-source software for a while is bound to notice an interesting contradiction between what open-source hackers say they believe and the way they actually behave - between the official ideology of the open-source culture and its actual practice. Cultures are adaptive machines. The open-source culture is a response to an identifiable set of drives and pressures. As usual, the culture’s adaptation to its circumstances manifests both as a conscious ideology and as implicit, unconscious or semi-conscious knowledge. And, as is not uncommon, the unconscious adaptations are partly at odds with the conscious ideology.” [Raymond, 1998]

This is a call to flexibility and user focus, if we simply replace ‘open-source’ with ‘UX’ we get a pretty good ethos for UX development.

8.7.1 Optional Further Reading

- [A. Cockburn.] Agile software development. Addison-Wesley, Boston, 2002.

- [A. Davies A] and J. Mueller. Developing Medical Apps and mHealth Interventions. Springer: Cham, Switzerland; 2020.

- [R. C. Martin.] The clean coder: a code of conduct for professional programmers. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2011.

- [A. Oram] and G. Wilson. Beautiful code. O’Reilly, Beijing, 1st. ed edition, 2007.

- [E. S. Raymond.] The cathedral and the bazaar: musings on Linux and Open Source by an accidental revolutionary. O’Reilly, Beijing, rev. ed edition, 2001.

- [I. Sommerville.] Software engineering. Pearson, Boston, 9th ed edition, 2011.

- [The Agile Alliance,] Website http://www.agilealliance.org/.

8.7.2 International Standards

- [ISO/TR 9241-100:2011.] Ergonomics of human-system interaction — part 100: Introduction to standards related to software ergonomics. TC/SC: TC 159/SC 4 ICS 13.180; 35.180, International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

9. Prototyping and Rapid Application Development

“If a picture is worth 1000 words, a prototype is worth 1000 meetings.”

– David & Tom Kelley, Founder, and Partner of renowned Design and Innovation Consultancy IDEO

In this chapter we’re going to be looking at Rapid Application Development (RAD) and Prototyping. By prototyping we simply mean a mock up that can (often) be run. And when we say run we mean this could be a wizard-of-oz kind of run, in that sense, whereby there’s a person behind the screen making it work. Alternatively, it could be actually running to a certain level of accuracy which could be implemented in part and parts that might not be implemented. So it just depends, but run means that things can be looked at by users. And you can work through the steps of how things might work.

In this case, the initial investment is low in terms of time and coding, because it’s really a prototype, it’s not the real thing and so hasn’t taken the development effort required to make everything work. Its job it to just allow the user to get closer to what the system could look like and how it could work without making a high initial investment, and as such it is cheaper in the initial development but also allows a user to make rapid changes over time.

9.1 Prototyping

UX prototyping refers to the process of creating interactive and tangible representations of user experiences. It involves building low-fidelity or high-fidelity prototypes that simulate the functionality, flow, and visual design of a digital product or service. UX prototyping plays a crucial role in the user-centred design process, allowing designers and stakeholders to gather feedback, test concepts, and iterate on designs before the actual development phase.

Key aspects of UX prototyping focus on:

User-Centric Approach: UX prototyping focuses on understanding and addressing user needs and expectations. By creating prototypes, designers can gather user feedback early in the design process and make informed decisions based on user insights.

Interactive Simulations: Prototypes are designed to simulate user interactions and workflows, providing a realistic representation of how the final product will behave. This allows designers to test and refine the user experience before investing in development.

Low-Fidelity Prototypes: Low-fidelity prototypes are quick and simple representations of design concepts, often created using paper sketches or digital wireframes. They are useful for exploring and validating initial ideas, gathering feedback, and making early design decisions.

High-Fidelity Prototypes: High-fidelity prototypes are more detailed and visually polished, closely resembling the final product. They can be interactive, allowing users to navigate through screens, interact with elements, and experience the product’s functionality. High-fidelity prototypes are valuable for user testing, stakeholder presentations, and demonstrating the user experience to clients.

Iterative Design Process: UX prototyping facilitates an iterative design process, enabling designers to make improvements based on user feedback. By testing and refining prototypes, designers can uncover usability issues, identify areas for improvement, and iterate on the design until it meets user and business goals.

Collaboration and Communication: Prototypes serve as a visual and interactive communication tool, enabling designers to effectively communicate their ideas to stakeholders, developers, and other team members. Prototypes bridge the gap between design and development teams, aligning everyone on the project’s vision and goals.

Prototyping Tools: Various prototyping tools are available that aid in creating interactive prototypes, such as Sketch, Adobe XD, Figma, InVision, and Axure RP. These tools offer features like drag-and-drop interfaces, interactions, animations, and the ability to simulate user flows.

Overall, UX prototyping is a powerful technique that empowers designers to iterate, test, and refine their designs based on user feedback. By incorporating prototyping into the design process, teams can create more user-centred and effective digital products and services. We will be focusing on the fidelity spectrum which runs from lo-fidelity at one end, and hi-fidelity at the other.

9.2 The Fidelity Spectrum

What you’ll find is that there are two extremes of prototypes; lo fidelity prototyping and hi fidelity prototyping. And as we move from lo fidelity to hi fidelity there is really a spectrum, and a diversity of change such that lo-fi facilitates big changes which become increasingly small as you move through to hi-fi. This is because there’s more work and more cost involved in the hi-fi. Also, as we’ve seen the closer you get to hi fidelity prototypes, the less likely it is a user will want to make changes because they’ll feel you’ve already put a lot of work into it. So really make sure that the users have been involved on the lo-fidelity prototypes, just so that you can understand any final changes or issues that need to be fixed from a user perspective, realising you are not going to get these to the level of large changes the closer you get to hi-fi prototyping.

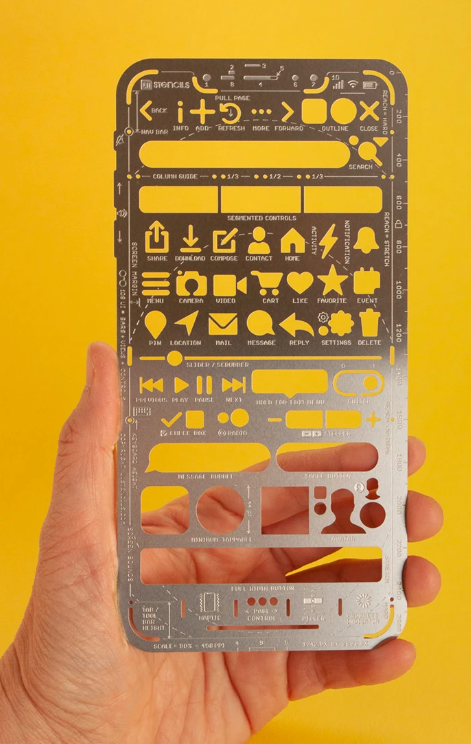

Along the spectrum you can increasingly refine the lo-fi prototypes moving from hand drawn prototypes to templates that are still lo-fi but look much more professional, giving a more exact representation of the artefact. We can see that the lo-fidelity prototypes above are mainly freeform and are created so they look like handwritten prototypes, none-professionally drawn drawings. This is a positive thing as people don’t get scared of making changes. But once you want to make it a little more formal you need to factor in the point that people will be more resistant to change.

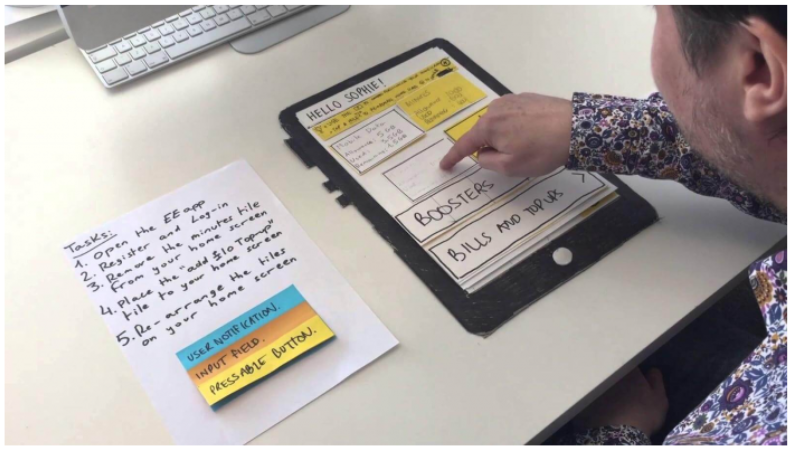

Initially, it’s still a person just drawing with a little linkage here and there. You shouldn’t undervalue this, the value of prototypes, especially of lo-fidelity prototypes is their ability to be changed by anyone (professionals and users alike). And so designers in large companies tend to use lo-fidelity prototyping. One example is the Nintendo Miiverse, one of the original Nintendo designs which utilises a three dimensional box that you hold and pull and push the cards from the top of it. Indeed, designer Kazuyuki Motoyama explains that the only way to actually know what a Miiverse would feel like was to hold it. That’s when he built this prototype out of cardboard.

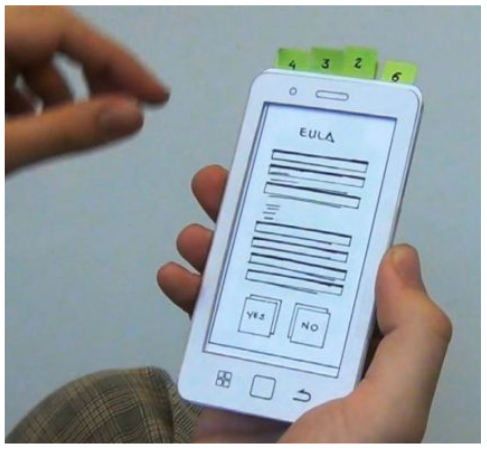

9.2.1 Nintendo Miiverse

Miiverse was actually modelled on Wii U prototype (which was intended to be one conjoined system) three dimensional box that you hold and pull and push the cards from the top of it. So you can see exactly what will happen when a button is pressed. What’s more, oftentimes, you’re moving to a certain set of tasks so that you don’t get things wrong. So it will tell you what to do. For instance, if you press this button, this will happen. And then you reveal that by removing (or adding) the card. So you are if you like running it yourself, if you like you can get these kinds of index card templates, whereby you have the mobile app on them, and then you can spread them on your desk so that you can show people how things are going to happen, move these templates around, which is quite a nice way of doing it. Once you turn it over, it can tell you the kind of tasks and the things that are expected to be accomplished. And in some cases, it’s got a reverse. So you know, if you click a button you clicked over, and then it’s got the button clicked on the other side. So you can have different forms of this. But it’s all to get this kind of level and feeling of what this thing is going to be like.

9.3 Prototypes in Software Engineering

Being a software engineer, there’s always the desire in a lot of ways to just get moving, to get moving on the actual interface, don’t bother about design, just get moving on it, get something out there. That’s a useful way of doing it when you’re trying to get an idea about what it is that you’re trying to create. When you need to know something about the systems that you’re trying to create and what they’re trying to do. And if you don’t know that yet, then it can be problematic without an initial interface model.

Now, when we talk about cowboy coding, this is what we mean in a prototyping context. Agile presumes that you’ve got some idea about what it is you’re building, if you have no idea about what it is you’re building, then cowboy coding kicks in. We just start making lots of lo-fidelity prototypes out there trying to get people to use them and understand which is the best one, which isn’t without a real clear idea necessarily. But that’s because if you don’t have an idea about what’s required, or what you’re going to build, because it’s so novel, then you’ve got to find some way of doing it.

As we’re seeing, increasing development increases fidelity. Once we have moved along from lo-fidelity then we get into common graphics or flow charting apps, such as sketch, Illustrator and OmniGraffle. And these things can actually also generate some kind of metadata to allow you to better create the screens etc. And then we get to the high fidelity prototype, which is really just to all intents and purposes, a visual designer for a screen but without any data. And then you’re able to create the interface and screens and add dummy plug in data in the back of it.

We’re going to talk about the separation of concerns soon enough, however we can see how this might work in prototyping as the interface is separated from the data on the interface (and this data is the result of programme logic). When we think about separation of concerns, even in high fidelity prototypes, it allows us to create the interface for different targets, might be mobile, might be desktop, different kinds of targets, we create the prototype, we create the interface for that target, but then we need the actual programming logic. And so we can then build the programme logic at the back. And this is where it really is useful to have some kind of RESTful interface decoupling of the programme logic from the interface itself. Or aspects like micro services, whereby you can develop parts independently of the other parts of the system. So you can build it up in that kind of separated way.

People are excluded from hi-fidelity prototypes, because you need more knowledge of how to use tools, whereas lo-fidelity, you just need to know how to use paper and pen. It’s pretty ubiquitous currently. Lo-fidelity prototypes allows you to think with your hands and not be too bothered about what things might look like, and what decisions you’re making, because it’s easily changeable by rubbing out with a pencil with an eraser or scrubbing over a pencil and drawing the lines and that kind of thing. So it’s a lot easier to do. It allows you to to make lots of validation steps of what’s required with users very quickly within in the space of a few days, because you can make the changes very quickly.

| HIGH-FIDELITY PROTOTYPE | LOW-FIDELITY PROTOTYPE | |

|---|---|---|

| Interactivity | ||

| Clickable links and menus | Yes: Many or all are clickable. | No: Targets do not work. |

| Automatic response to user’s actions | Yes: Links in the prototype are made to work via a prototyping tool (e.g., InVision, PowerPoint). | No: Screens are presented to the user in real time by a person playing “the computer.” |

| Visuals | ||

| Realistic visual hierarchy, priority of screen elements, and screen size | Yes: Graphics, spacing, and layout look like a live system would look (even if the prototype is presented on paper). | No: Only some or none of the visual attributes of the final live system are captured (e.g., a black-and-white sketch or wireframe, schematic representation of images and graphics, single sheet of paper for several screenfuls of information). Spacing and element prioritization may or may not be preserved. |

| Content and Navigation Hierarchy | ||

| Content | Yes: The prototype includes all the content that would appear in the final design (e.g., full articles, product-description text and images). | No: The prototype includes only a summary of the content or a stand-in for product images. |

And it allows for ‘user centred design’ whereby the user is actually more part of the process. Because with user centred design, we want the users to be involved in the process, not excluded, and most users won’t have the skills to use SketchUp or OmniGraffle, or even the hi-fidelity generation engines. Further, they’re not as free in their designs if they have to have somebody else do that for them. So even though there might be two people together designing the system, users who wants the designer to make a change in a hi-fidelity prototype is going to be much more reticent because they think it will be more work.

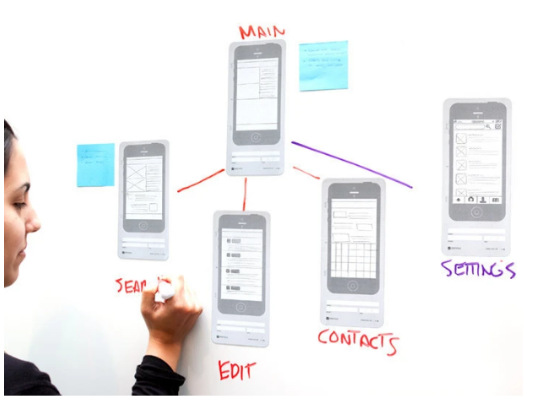

9.4 Users, Commissioners, Engineers!

Prototypes are used with users, with commissioners, and with engineers and typically in that order from lo to hi fidelity. So what would normally happen is that you’d have users who would look at these lo-fidelity prototypes that have been drawn freehand (say) just written on post it notes, so you can move things around quickly, you might then firm that up into something that’s mid range. So it’s more along the lines of an actual computer generated hierarchy using SketchUp, etc, which is something that a lot of designers use in developing designs, and so you can see what’s going on at this stage. Now, remember, everything I’m talking about when it comes to prototypes is visual; I’m not talking about any prototypes for conversational interfaces, or zero UI, or auditory design, because most users don’t think about these aspects in the early stages of the design. So as you’re a UX’er, you’re going to have to think about how to do for non-visual prototyping because there’s no best practice out there.

So commissioners will expect the system to look more professional and they will be expecting to make minimal to no changes, however, it still might not be the final design. But with the engineers, you’re probably going to create something that’s the final thing, you’re probably likely to let the commissioners see that as well at one of the development meetings, but mainly then, with the engineers, you can make the changes and generate out something for the engineers to start work on.

As a UXer, you’re probably going to start work on the low fidelity prototypes and this is typically because you’re going to be working more with the users, once it gets to the visual designers, they’re going to be using mid range SketchUp like applications. So they’ll do the visual design there. Now translating that visual design to the hi, very hi-fidelity prototypes ready to generate out for the engineers might be your job again, because really, you’re translating the visual design into something that can then be created as the basis for code. Or it might be an engineer, or it might be a specialist visual designer.

9.5 Rapid Application Development

Rapid Application Development is really the boundary of these hi-fidelity prototype tools. And now, hi-fidelity prototyping tools have taken over the space of rapid application development. RAD was a 1991 era idea or at least it was expressed in that idea whereby we needed to create applications quickly without any sort of background machinery such that users could see what was going to be there and is heavily reliant on prototyping. And so this is kind of a method of doing the prototyping. In this case, RAD is a software development methodology that prioritizes speed and flexibility in delivering high-quality applications. It emphasizes rapid prototyping and iterative development cycles to quickly build and deploy software solutions. RAD aims to accelerate the development process, reduce time to market, and improve customer satisfaction by involving end-users and stakeholders throughout the development lifecycle. Key characteristics and principles of Rapid Application Development are

- Iterative Approach: RAD follows an iterative development model, where software is developed in small increments or prototypes. Each iteration focuses on specific features or functionalities, allowing for quick feedback and continuous improvement. This is a lot like the newer concept of Agile - which is now tied to UX.

- User-Centric Focus: RAD places a strong emphasis on user involvement. Users and stakeholders are actively engaged throughout the development process to gather requirements, validate prototypes, and provide feedback. This ensures that the final product meets user expectations and addresses their needs effectively.

- Prototyping: RAD heavily relies on prototyping techniques to rapidly build and refine software solutions. Prototypes are created early in the development process to demonstrate the application’s core functionality, interface, and user experience. User feedback is incorporated into subsequent iterations, leading to an evolving and user-centric design. This is the critically important part of RAD for UX and we might even extend this to imply that an initial software framework can be generated from a hi-fidelity prototype.

- Collaboration and Teamwork: RAD promotes close collaboration among developers, users, and stakeholders. Cross-functional teams work together to define requirements, design prototypes, and deliver working software in short development cycles. Effective communication and teamwork are crucial to the success of RAD projects.

- Reusable Components: RAD encourages the reuse of existing software components and modules. By leveraging pre-built components, RAD speeds up development and reduces the effort required to build certain features. This approach enhances productivity and allows developers to focus on unique requirements and functionality.

- Parallel Development: RAD enables parallel development activities by dividing the project into smaller modules or components. Different teams or developers can work on these modules simultaneously, ensuring faster development and integration of various software components.

- Flexibility and Adaptability: RAD emphasizes flexibility and adaptability to changing requirements. The iterative nature of RAD allows for adjustments and refinements based on user feedback and evolving business needs. This enables the software to evolve and align with changing market dynamics.

- Time and Cost Efficiency: By employing rapid prototyping, iterative development, and close collaboration, RAD can significantly reduce development time and costs. The focus on early user involvement and continuous feedback minimizes rework and ensures that the final product meets user expectations.

It’s important to note that RAD is not suitable for all types of projects. It is best suited for projects with well-defined scope, clear business objectives, and actively involved users and stakeholders. RAD is particularly effective in situations where time to market is critical or when requirements are subject to change.

Overall, Rapid Application Development offers a dynamic and flexible approach to software development, enabling faster delivery of high-quality applications while maintaining a user-centric focus. If you’re working in RAD (or at least a close variant), then you also need to make sure that the system you’re using will generate an application that can run and that can be populated with fake data, but that cannot have any real programme logic. For the interface, it will display content which is understandable by a user and it might also then have links to databases in the background and it can become increasingly complex as development and modelling proceeds. RAD is not just about user experience it’s also about any system development via higher level languages and so you can also generate, for instance, a database application via flowcharts via state transition diagrams via UML. So any system development will utilise RAD because it’s a faster transition from the design phase to the application phase.

9.5.1 RAD & Prototype Comparison

RAD and Prototyping are both software development approaches, but they differ in their objectives and the stages of the development process they focus on. However, there is clear linkage in that RAD heavily utilises prototyping and prototyping at the very hi-fidelity often include the ability to generate a working RAP prototype for user involvement and as a kickstart to the initial development effort.

9.5.1.1 Objectives

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): RAD aims to expedite the development process by emphasizing iterative development and quick delivery of functional software. Its focus is on rapid iteration and user feedback to ensure that the final product meets user requirements.

- Hi-Fidelity Prototyping: Hi-Fidelity Prototyping focuses on creating highly detailed and interactive prototypes that closely resemble the final product. The goal is to test and validate the design and user experience before investing significant resources in development.