Part IV: Validating the User Experience

14. User Evaluation

Life is a full circle, widening until it joins the circle motions of the infinite

– Anais Nin

Evaluation methodologies are the principal means by which the UX specialist answers the questions ‘What needs to be done?’, and after an interface manipulation has occurred, ‘What is the effect of this manipulation?’

There are many ways to categorise different evaluation methodologies within UX. Here I equate naturalistic field evaluation with the qualitative methods of anthropologists, I see quantitative methods, characterised by sociological surveys, as being between fieldwork and laboratory experimentation (we’re already looked at these). Finally, I see laboratory-based evaluation, mainly in non-naturalistic settings, as being the main way of enacting true experimental methods most often used within experimental psychology and the cognitive sciences.

Each of these key categories has a unique way of viewing the world and a particular set of strengths arising from the kind of evaluation and answers needed. There are many debates within each particular discipline as to the kind of methods that give the best outcomes. However, in UX we can take a more pragmatic approach and select the appropriate evaluation method from each category, combining them all together in our final experimental design, so that we can build an end-to-end story.

If you notice, I’m using the term ‘evaluation’ quite frequently. This is because these methods all evolved from scientific evaluation methods within a particular academic discipline. But do not be confused, their applicability to real-world scenarios and their use within practical settings, of the kind we often face in application and interface development, is what has made them popular and particularly suited to the kinds of questions the UX specialist is required to answer.

Evaluation methods are slightly different from the kind of requirements analysis and requirements elicitation scenarios that we have seen. As we state there, requirements analysis and elicitation, along with the models that are created from them, are often engineering – or craft based – as opposed to having their roots within empirical scientific methodologies; certainly this is the case informally. In this case, they are more akin to the qualitative evaluation methods of participant observation, interviewing, or focus group discussion. However, these three methods are not bound with the same kind of system architecture design metaphors and methods as are those of requirements analysis. It is my opinion that this makes requirements analysis far weaker than the evaluation methods we will discuss here. I would only hazard a guess, which this is the case because the final testing of the software system will validate or invalidate the requirements model, whereas, there is no such concept of a final implementation validating an evaluation method in the domain of anthology or sociology. This means that, if the model is wrong, a large amount of time is needed to fix it at the end of the project. In some cases, this means that the interface is left unfixed because time and cost constraints dictate a speedy completion.

Understanding the requirements – and having the tools to create experimental methods to test the interface is correctly created from those requirements – are key to the user experience. As such, this chapter should be one of your primary references when creating testing and evaluation plans involving the user.

14.1 Expert Evaluation via the Audit

Walk-throughs and heuristic evaluations are closely linked and listed here because they are slightly different from the other techniques introduced. They differ because they mainly occur before formal evaluation with participants and are often conducted by the evaluator, or the UX specialist responsible for creating the interface, themselves.

14.1.1 Walk-throughs

There are many flavours of walk-throughs including the cognitive walk-through and the barrier walk-through, along with the code walk-through. However, in all cases, the evaluator formally addresses each step of the system based on the interaction that is required and the system components that are required to enact that interaction. At each stage, the outputs, inputs, and performance will be evaluated, and this presupposes that the walk-through is far more about an evaluation of the system performing correctly than it is about the aesthetic or design nature of the interface itself. In this case, walk-throughs can also be used to understand how easy the system is to learn and whether aspects of usability, such as progressive disclosure, or accessibility are present. However, to create a reasonably accurate walk-through the evaluator needs to have a good understanding or description of the prototype system; a description or understanding of the task the users are to perform; the action that is required to complete the task; and an indicator of who the users will be. This last indicator is particularly difficult in that it presupposes the evaluator understands all aspects of a user’s behaviour and character that, as we have seen, can be particularly difficult to assess.

14.1.2 Heuristic Evaluation

Related to the walk-through is the heuristic evaluation. This approach differs from the walk-through only in that there are specific aspects that need to be assessed as the evaluation proceeds. These aspects are based upon the general principles that have already been covered. However in this case, as opposed to the developer walking through the different scenarios of user interaction, a set of evaluators are asked to independently answer questions regarding the usability of the interface, rating different aspects as they go. Once complete, average ratings can be generated for all aspects of the interface based on the consensus opinion of the evaluators. This is a reasonably effective method and is often used as an initial test before the main evaluation begins.

In both cases an expert user, or key participant (informer), is required to perform these evaluations and the results of the evaluation are very much based on the skills, ability, and knowledge of the evaluator. In reality, this means that the principles that you have learnt should be reapplied back into development, but this time as questions. These questions may take the form of ‘Is the need to Facilitate Progressive Disclosure met?’, ‘How is Progressive Disclosure met?’, or the questions to think about when designing your prototype to Facilitate Progressive Disclosure) – such as ‘Is there a tight logical hierarchy of actions?’ – could be used as metrics for understanding the success of failure.

14.2 Qualitative (Fieldwork) Methods

Anthropologists and sociologists describe field evaluation variously as fieldwork, ethnography, case study, qualitative evaluation, interpretative procedures, and field evaluation. However, among anthropologists fieldwork is synonymous with the collection of data using observational methods. For the sociologist, the term often describes the collection of data using a social survey. While it was often thought that these two competing methods of qualitative and quantitative evaluation are disjoint, many sociologists also utilise participant observation, structured interviews, and documentary evidence as interpretive methods. These methods owe much to social anthropologists following the theoretical tradition of ‘interactionism’; interactionists place emphasis on understanding the actions of participants by their active experience of the world and the ways in which their actions arise and are reflected back on the experience. This is useful for the UX specialist as the interactionists component of the method makes it quite suitable investigating subjective aspects.

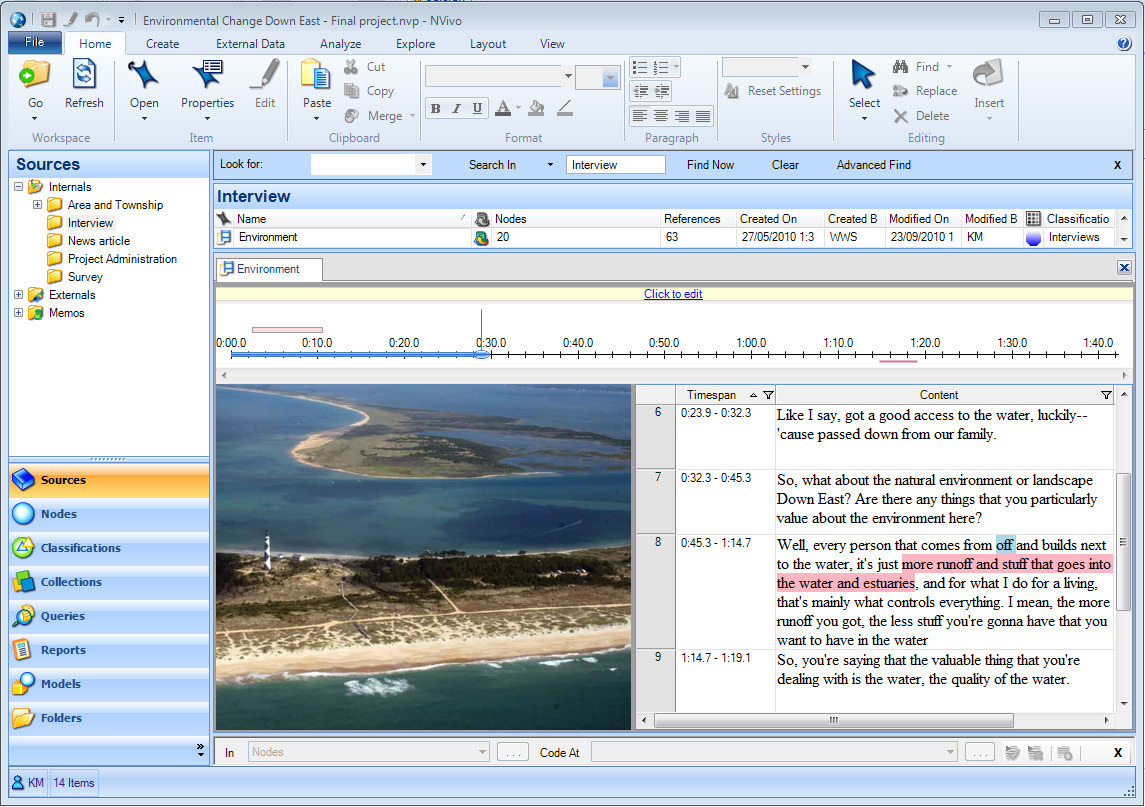

To support these methods and strategies, many suggest the simultaneous collection and analysis of data. This implies the keeping of substantive field notes consisting of a continuous record of the situations events and conversations in which the practitioner participates [Van Maanen, 2011]; along with methodological notes consisting of personal reflections on the activities of the observer as opposed to the observed. The field notes should be preliminary analysed within the field and be indexed and categorised using the standard method of ‘coding’ different sections of the notes to preliminary categories that can be further refined once the fieldwork has concluded.

The most used methods on qualitative evaluation are participant observation, interviewing, archival and unobtrusive methods. I suggest that these methods are mainly used for building a body of evidence that is deep but narrow in extent and scope. The evidence can then be used to help generate hypotheses, and understanding, to be confirmed in later tests. In this case, aspects of Mills Method of Agreement can be used to build evidence before the computational artefact, the application, utility, software, or system is created. Indeed, these methods will give you an idea of what to build or what is wrong with whatever already exists.

14.2.1 Unobtrusive Methods

Imagine you have been employed by the local library to review the number and placement of cataloguing terminals that can be used for book searches by the general public. If these terminals are all placed together large queues form, and besides, members of the public must return from the area of the library, they are in, to the area that houses the centralised terminals if they wish to evaluation the catalogue. To determine how many terminals are required, and in what locations, you may wish to conduct an analysis of floor tile wear, by visual inspection and also by consulting the maintenance records of the library. In this case, you will be able to understand the amount of traffic to each of the different library sections and optimise the placement of terminals along these routes and in these areas. If you decided to use this approach then, you would be using a methodology that is unobtrusive to the participants (in this case library users).

‘Unobtrusive methods’ is a phrase first coined in 1965/66 and the book in which it was first proposed has since become a classic [Webb, 1966]. Simply, unobtrusive methods propose that evaluations should look for traces of current activity in a similar way to the way archival material is used as a past by-product of normal human activities. This unobtrusive way of investigation is important because in direct experimentation unintended changes can occur, as part of the investigator intervention, which skew the findings (think ‘Bias’).

These sources of invalidity can be roughly categorise as ‘reactive measurement effect’ or ‘errors from the respondent’ such as:

- The guinea pig effect, whereby people feel like guinea pigs being tested in experiments and so, therefore, change their behaviour patterns;

- Role selection, whereby participants see the experimenter as taking a certain role, having an elevated status above the participant, who therefore follows that experimenters lead;

- Measurement as change agent, in which aspects of the initial measurement activity introduces real changes in what’s being measured; and finally,

- Response sets, whereby respondents will more frequently endorse a statement than disagree with its opposite.

Also, errors from the investigator can also be introduced. These range from the interviewer effect, whereby characteristics of the interviewer contributes to the variance in findings because interviewees respond differently to different kinds of interviewer based on the visible and audio cues which that interviewer gives. And changes in the evaluation instrument, whereby the measuring instrument is frequently an interviewer, whose characteristics we have just shown may alter responses, yet that interviewer changes over the course of the investigation. To overcome these possible errors, all contact with participants is removed, and the practitioner bases their findings on observation – Simple Observation – of both the participants and the environment.

Simple observation is the practice of observing exterior physical signs of people as they are going around their normal business along with the expressivity of their movement and their physical location in conjunction. This kind of observation can be extended to include conversation sampling, and time duration sampling for certain observable tasks. Of course, enhanced observational techniques known as contrived observation may also be undertaken. Here techniques such as hardware instrumentation can be particularly useful for different kinds of computer-based activity as long as ethical considerations are taken into account. In general, unobtrusive methods take a holistic approach of the participant, the task or activity, and the environment. By observing, but not intervening or questioning, the UX specialist can understand the interaction activities and interface issues of individuals enacting a real system in a natural setting without disturbing or affecting that system. We can see how unobtrusive methods can be applied to understanding the user experience from a social perspective in.

14.3 Quantitative & Hybrid Methods

As we have seen, qualitative methods are mainly used for building a body of evidence that is deep but narrow in extent and scope. The evidence can be used to help generate hypotheses, and extend understanding, to be confirmed in later experiments. Simply, hybrid and quantitative methods give the UX specialist the tools and techniques to enact these confirmatory experiments [Tullis and Albert, 2008]. Questionnaires, also know as survey methods, are probably the most flexible and useful tools we have for gathering this kind of confirmatory information. They are widely used in the social sciences, as the main form of a systematic method for empirical investigation and critical analysis, to develop and refine a body of knowledge about human social structure and activity.

However, questionnaires have some facets that need careful consideration if the quantitative results produced by their application are to be valid. For instance, questionnaires already make many assumptions regarding the domain under investigation, obviously, the mere activity of asking a specific question has some very implicit assertions associated with it. Therefore, even questionnaires that look to be appropriate may in-fact, be biassed. Indeed, practitioners have criticised the tradition that has allowed questionnaires to become the methodological sanctuary to which many UX specialists retreat. In this context, the most fertile search for validity comes from a combined series of different measures each with its idiosyncratic weaknesses each pointing to a single hypothesis. In this case, when a hypothesis can survive the confrontation of a series of complementary methods of testing it contains a degree of validity unattainable by one tested within the more constricted framework of the single method. Therefore, practitioners have proposed the hybrid method; also known as mixed methods or triangulation. Here, many complimentary methods are used and indeed this approach is the one I would espouse for most UX work.

Methods that I classify as between field and laboratory are meant to signify quantitative methods used to retest knowledge derived from qualitative investigations and confirm the initial hypothesis selection process. While, quantitative methods are often used as the only method applied to many social science questions, in UX they do not stand up as verifiable when evaluating or testing an interface or human facing system. A more rigorous approach is required in this case in which experimental metrics can be directly applied in a controlled environment.

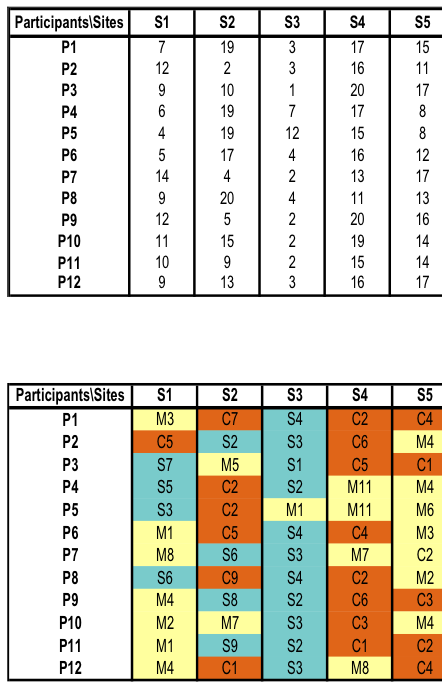

14.3.1 Card Sorting

There are several well-understood experimental methodologies used for knowledge elicitation. One such methodology is card sorting techniques used along with triadic elicitation techniques to capture the way people compare and order different interfaces based on different criteria. This framework allows the UXer to investigate both qualitative and quantitative aspects of the user experience while recognising that participants are difficult to recruit. By using card sorting methods, you can produce a quantitative analysis with a definite error rate and statistical significance, and by using triadic elicitation, you can also accommodate the most illusive aspects of the user experience and add depth to the quantitative data.

Card sorting is the simplest form of sorting. During this procedure, the participant is given many cards each displaying the name of a concept (or images / wireframes / screenshots, etc.). The participant has the task of repeatedly sorting the cards into piles such that the cards in each pile have something in common. By voicing what each pile has in common, or the difference between each pile, or description of the characteristics of each pile, the participant is vocalising implicit knowledge they have about the things on the cards.

Suppose we wish to find the attributes of a Web page, by which it is judged as simple or complex. Here, the cards are a screen-print of each Web page that was used for testing. With the continuous sorting, the participant is unintentionally giving information on the attributes and values to describe the characteristics of each Web page, describing the reasons for the perceived complexity.

Triadic elicitation is often used along with card sorting techniques. During this technique, the user is asked about what they think is similar and different about three randomly chosen concepts and in what way two of them similar and different. This technique is used to elicit attributes that are not immediately and easily articulated by the user and helps to determine the characteristics of the card sorted concepts. Further, picking three cards forces us into identifying differences between them – there will always be two that are closer together, although which two cards that are may differ depending on your perspective. The application is very simple. Basically, you select three cards at random, you then identify which two cards are the most similar. Now analyse what makes them similar and what makes them different.

14.3.2 Socio / Unobtrusive Methods

There are many ways to conduct unobtrusive observations within the user experience domain, these might range from remote observations in the real world – of peoples mobile phone usage, say – to collecting data via proxy methods and based on website usage, etc. UX can be unobtrusively measured, directly or indirectly; individually or collectively. And by having the proper metrics, UxD can be leveraged towards the constant improvement of products and services. And this can, I argue, be replicated and generalised across products and services. Let’s have a look at kinds of metrics that can be used.

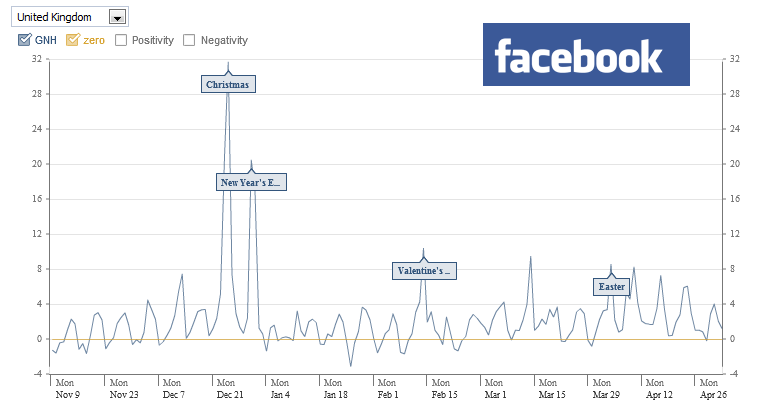

Analytics (PULSE + HEART) [Rodden et al., 2010], Social Sensing or Net Promoter Score Are unobtrusive observational methods that collected and – better still – combined enable us to understand how people feel about a website or desktop application. PULSE – Page views, Uptime, Latency, Seven-day active users (i.e. the number of unique users who used the product at least once in the last week), and Earnings (for instance see Google Analytics PULSE Example – can be derived from standard quantitative data, however HEART – Happiness, Engagement, Adoption, Retention, and Task success – requires a little more social networking and user monitoring. In both cases, by understanding the quantity, types, and return rates of users we can infer favourable experiences once we have some social sensing data. My rational here is that analytics provides us with information that is all inferential – people may return to the site not just because they like it but because they have no choice because they want to complain because they found it difficult last time. But if people are also tweeting, Facebook ‘liking’ then you can expect that if this figure is say 20% then over 60% will like the site but can’t be bothered to ‘Like’ it – this is the same with Net Promoter Score1.

How to capture the user experience in a single session, this is difficult with any degree of accuracy. This could be thought of as the kind of user evaluation method you will become used to. In reality, one session does not make a good evaluation, you should think about the possibility of introducing proxies2 to collect longitudinal usage data.

Mindshare goals – qualitative measures such as awareness, branding effectiveness. In general how much chatter is there in the media, around the coffee machine, water cooler, about your application or site. Lots either means love or hate, silence means mediocre. This is mainly a marketing metric, applied with few changes into the UX domain – indeed, there are some obvious similarities between Mindshare and Social Sensing as discussed in ‘Analytics…’.

Customer support responsiveness and Customer satisfaction evaluation. Quantitative and qualitative loyalty. This is a general purpose quantitative and qualitative interview or questionnaire in which consumer satisfaction can be elicited on a wide scale with deployed resources. You normally find this kind of thing in Social Science, and these techniques haven’t changed much in the move to UX. One interesting development is their combination with social metrics such that peer review is provided by giving star ratings to various resources, or as part of ‘Net Promoter’.

Now these methods should interest you (for example see Facebook ‘Gross National Happiness Index’) – not least because their creation, application, and the inferences made from the resultant data tie into user feedback without participant bias. As we’ve previously seen, UX pays more attention to the individual and subjective realm in which ‘intangibles’ are required to become tangible for testing purposes – so that user feedback can be factored into the new design.

So how do we form these methods into a cohesive framework, well the jury is still out, but Google think it is via Goals, Signals, and Metrics.

Goals: “The first step is identifying the goals of the product or feature, especially regarding user experience. What tasks do users need to accomplish? What is the redesign trying to achieve?” Signals: “Next, think about how success or failure in the goals might manifest itself in user behaviour or attitudes. What actions would indicate the goal had been met? What feelings or perceptions would correlate with success or failure? At this stage, you should consider what your data sources for these signals will be, e.g. for logs-based behavioural signals.” Metrics: Finally, “think about how these signals can be translated into specific metrics, suitable for tracking over time on a dashboard” again playing into longitudinal observation —Google.

14.3.3 A Short Note on Longitudinal Observation

Observation of user behaviour when interacting with applications and the Web – especially for the skill gaining process – is better observed at a longitudinal fashion. This statement is founded on the fact that increased intervals enable the consolidation of declarative knowledge in long-term memory, where consolidation does not happen automatically, and it is not determined at the time it has been learned. To gain insights into the user experience in the context of your development, we should conduct a longitudinal analysis of those users if at all possible.

14.3.4 Think-Aloud

It is sometimes difficult to understand exactly what the user is thinking or, in some cases, doing when they are navigating a complex interface. This is especially the case when the user is familiar with the interface and interaction, and may even be undertaking different, but related, tasks at the same time as the primary task. In this case, to understand explicitly the activities and thoughts of the user, as they are performing the interaction, the think aloud methodology can be used [Lazar et al., 2010].

The think aloud methodology is a classic of the UX evaluation process evolving mainly from design-based approaches (created by Clayton Lewis while at IBM). It produces qualitative data and often occurs as part of an observational process, as opposed to a direct measurement of participant performance, as would be normal in laboratory settings. While it is true that think aloud requires tasks to be completed, the object is not the direct measurement of those tasks. Instead, it is the associated verbalisations of the participants as they progress through the task describing how they are feeling and what they think they need to do.

Think aloud is intended to produce data which is deeper than standard performance measures in that some understanding of the thoughts, feelings, and ideas that are running through the mind of the participant can be captured. The main problem with think aloud is, also its strength in that, it is very easy to set up and run, and therefore, the design aspect of the tasks can be ill conceived. In this way, it is often easy to implicitly influence the participant into providing outcomes that are positive regardless of the true nature of the interface or interaction. Indeed, the very act of verbalising their thoughts and feelings means that participants often change the way they interact with the system. It is for this reason that think aloud should not be used as a methodology on its own but should provide the qualitative aspects lacking in other quantitative or performance-based measures.

14.3.5 Co-Operative Evaluation & Participatory Design

As we have seen3 Co-operative evaluation and participatory design are closely related techniques that enable participants to take some form of ownership within the evaluation and design process. It is often thought that these participants will be in some way key informants, as we have seen in participant observation, and will therefore have an insight into the systems and interfaces that are required by the whole. Both methods are closely linked to the think aloud protocol, but instead of entirely focusing on evaluation the users are encouraged to expand their views with suggestions of improvements based on their knowledge of the system or interfaces that are required. Indeed, the participants are encouraged to criticise the system in an attempt to get to the real requirements. This means that in some cases a system design is created before the participatory or co-operative aspects have begun so that the participants have a starting point.

UCD and cooperative evaluation are related approaches that emphasize the involvement of users in the design and evaluation of interactive systems. While user-centred design focuses on incorporating user feedback throughout the design process, cooperative evaluation specifically addresses the collaborative and iterative evaluation of a system with users. User-centred design involves understanding user needs, preferences, and behaviours through methods such as user research, interviews, and observations. This user understanding is used to inform the design of interfaces, products, or systems. Throughout the design process, user feedback is collected and integrated, ensuring that the final product meets user expectations and requirements.

Cooperative evaluation, on the other hand, is a specific technique within the user-centred design process. It involves actively involving users as partners in the evaluation and improvement of a system. Rather than solely relying on expert evaluations or usability testing, cooperative evaluation emphasizes the collaboration between designers, developers, and users to identify usability issues, gather feedback, and suggest improvements. In a cooperative evaluation, users are invited to provide input and insights on the system’s usability, user experience, and functionality. They may participate in various evaluation activities, such as walk-throughs, user testing, think-aloud protocols, or focus groups. Through this cooperative process, users can contribute their first-hand experiences, identify potential issues or challenges, and provide suggestions for enhancements or refinements.

The relationship between user-centred design and cooperative evaluation lies in their shared commitment to involving users throughout the design and evaluation process. Both approaches recognize the value of user input, perspective, and feedback in creating usable and effective systems. By combining user-centred design with cooperative evaluation, designers can engage users as active collaborators, fostering a user-centric approach that leads to more user-friendly and satisfying experiences.

Cooperative evaluation and participatory design are likewise related approaches that share several similarities in their focus on user involvement and collaboration; including:

- User Participation: Both cooperative evaluation and participatory design emphasize the active involvement of users in the design and evaluation process. Users are seen as valuable contributors who provide insights, perspectives, and expertise that shape the final product or system.

- Collaborative Approach: Both approaches foster collaboration and cooperation between designers, developers, and end-users. They encourage open communication, dialogue, and knowledge sharing among all stakeholders involved in the design process.

- User Empowerment: Cooperative evaluation and participatory design seek to empower users by giving them a voice in decision-making and allowing them to influence the design outcomes. Users are seen as experts in their own experiences and are encouraged to actively participate in shaping the design process.

- Iterative and Agile Process: Both approaches embrace an iterative and agile design process. They involve multiple rounds of feedback, testing, and refinement to ensure that user needs and expectations are addressed. The design is continuously adapted and improved based on the insights and feedback gathered from user participation.

- Contextual Understanding: Both cooperative evaluation and participatory design emphasize the importance of understanding the users’ context, needs, and goals. They aim to design solutions that are relevant and meaningful within the specific user context, promoting user satisfaction and usability.

- User-Centric Design: Both approaches prioritize designing for users’ needs and preferences, focusing on creating user-centric solutions. The insights gained through cooperative evaluation and participatory design help ensure that the final product or system aligns with user expectations and requirements.

While there are similarities, it’s worth noting that cooperative evaluation is primarily focused on evaluating and refining an existing system, while participatory design is concerned with involving users in the entire design process from ideation to implementation. Nonetheless, both approaches share a user-centred philosophy and highlight the importance of user involvement in the design and evaluation of systems.

The UX specialist must understand that co-operative evaluation, and participatory design are not fast solutions. Indeed, they should only be used when a firm understanding of the boundaries of the system is possessed. Also, participatory design often runs as a focus group based activity and, therefore, active management of this scenario is also required. Enabling each to fully interact within the discussion process while the UX specialist remains outside of the discussion just acting as a facilitator for the participants views and thoughts is a key factor in the process design.

14.3.6 Survey Questionnaires – Reprise

How do you find out if the system or interface that you have designed and deployed is useful and has useful features? What kinds of improvements could be made and in what order should these improvements be prioritised? To answer these kinds of questions, it is useful to talk to a large number of people, far more than you could expect to recruit for a laboratory experiment. In this case, you may decide to use a questionnaire-based survey, recruiting as many users as you possibly can.

Question-based surveys are usually designed to provide statistical descriptions of people and their activities by asking questions of a specific sample and then generalising the results of that survey to a larger population [Bryman, 2008] (for example Figure: Online Survey Example). This means that the purpose of the survey is to produce statistics and that the main way of collecting information is by asking people questions. In this case, there are three different properties of a good survey, being probability sampling, standardised measurement, and the special-purpose design. Components of a survey sample are based around the question design, the interview method (the questionnaire in this case), and the mode of data collection (verbal or written); all being taken together as total survey design. Critical issues are the choice of how the sample is selected, randomly or non-randomly, creating a probability or non-probability sample; and the sample frame, the size of the sample, the sample design, and the rate of response. One fundamental premise of the survey process is that by describing the sample of people who respond, one can describe the target population. The second fundamental premise of survey evaluation processes is that the answers people give can be used to accurately describe characteristics of the respondent. The sample frame describes the part of the population who have a chance to be selected. Also, if the sample is not random, then the respondents who answer are likely to be different from the target population as a whole. Surveys normally capture two different aspects: objective facts and subjective states. Objective facts include things like the person’s height, whereas subjective facts include, how much of the time the persons felt tired, say.

Designing questions to be good measures, which are reliable and provide valuable and valid answers, is an important step in maintaining the validity of a survey. Always avoid inadequate, incomplete, or optional wording while ensuring consistent, meaningful responses. Remove poorly defined terms and avoiding multiple questions conflated to be a single question. However, it is acceptable to include specialised wording for specialist groups. Remember, participants may be tempted to give incorrect responses if they have a lack of knowledge, or change their answers if they find it socially desirable. This should be pre-empted in the designing of the questions, in which questions should be created as reliably as possible. In addition, there are four different ways in which measurement can be carried out: nominal, people or events are sorted into unordered categories; ordinal, people or events are ordered or placed in all categories along a single dimension; interval, numbers are attached that provide meaningful information regarding the distance between ordered stimuli or classes; and ratio, in which numbers are assigned such that ratios between values are meaningful.

Survey questions should be evaluated before the survey is given using techniques such as focus groups, question drafting sessions, critical reviews, and more formal laboratory interviews. The questions should also be field tested before the main survey becomes available. Remember that survey interviewing can be a difficult job and the type of participant selection is critical in this case. For instance, the commonly used non-probabilistic quota based technique can be particularly troublesome as interviewers are left to survey a certain demographic profile to a certain quota size. This means that many aspects of the validity of a survey are left to the interviewer, who make non-random choices such as choosing houses that are of a higher value, in good areas, without pets or dogs; male interviewers will choose younger female respondents, and female interviewers will choose older male respondents. These biases should be accounted for within the questions and the design of the survey.

Survey methods can be very useful to the UX specialist for confirming qualitative work or evaluating systems that do not immediately lend themselves to the more rigorous laboratory-based methods that will be described in subsequent sections. In the real world, the UX specialist is often unlikely to be able to solicit enough respondents for completely accurate probabilistic methods, and it is more likely that non-probabilistic quota-based methods will be used. However, simple random sampling can be used if the sample frame is tightly defined, and in this case readily available ordinal identification, such as employee number, could lend itself to the selection process. While surveys should not be the only method used, they are useful for understanding general points regarding systems and interactions, over a large set of users who could not normally be evaluated in a formal laboratory setting.

14.3.7 Hybrid Methods

The hybrid method; also known as mixed methods or triangulation are terms used to denote the use of many complimentary methods because the UX specialist recognises the inadequacies of a single method standing alone. Indeed, the hallmark of being a field practitioner is flexibility concerning theoretical and substantive problems on hand. Therefore, the use of ‘triangulation’ (a term borrowed from psychology reports) is used to refer to situations where the hypotheses can survive the confrontation of a series of complementary methods of testing. Triangulation can occur as ‘data triangulation’ via time, space, or person; ‘investigator triangulation’ in which more than one person exams the same situation; ‘theory triangulation’ in which alternative or competing theories are used in any one situation; and ‘methodological triangulation’ which involves within method triangulation using the same method used on different occasions, and between-method triangulation when different methods are used in relation to the same object of study. Indeed, mixed methods contrast quantitative and qualitative work, characterising them by behaviour versus meaning; theory and concepts tested in evaluation versus theory and concepts emergent from data; numbers versus words; and artificial versus natural. In reality, for the UX specialist, the confrontational aspects can be thought of as being purely complimentary.

To a large extent, the UX specialist does not need to concern themselves with the methodological debates that are often prevalent within the human sciences such as anthropology, sociology, social science, and psychology. This is mainly because these methodologies and the instruments which are used within them are not directly created as part of the human factors domain but are used and adapted in combination to enable a verifiable, refutable, and replicable evaluation of the technical resource. In UX, a single methodology would not normally ever be enough to support an evaluation or to understand the interaction of technology and user. However, the view I take of the evaluation domain is far more holistic than may be found in most UX or user experience books. By reliance on only the evaluation aspects of a specific technical interface we miss the possibility of understanding how to make that interface better, not just by metrics as shallow as time to task, but by a combined qualitative and quantitative understanding of the factors surrounding user interaction, both cognition and perception, for a particular software artefact or system architecture.

14.4 Tools of the Trade

As a UXer, there are many tools that you can use both in a laboratory-based setting or in the field. Most tools are portable and so, therefore, can be moved around to different sites and venues such that you are more reactive to the locational needs of your participants; as opposed to expecting them to come to you4.

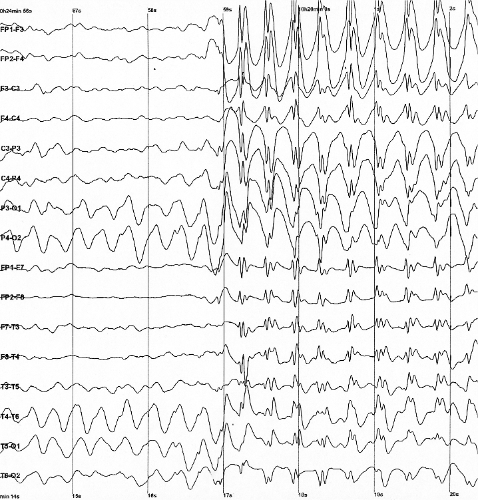

UX tools range from the very simple, such as the notebook, through audio recording devices, portable cameras and video cameras, screen capture and screen recorders, to the more complex (and costly) static and portable eye trackers, bio–feedback system such as galvanic skin response and heart rate monitors, through to neuro–feedback such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electro-encephalo-graphy (EEG — for example, see Figure: EEG Data Plot Example) , event-related potentials (ERPs), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) systems. All these tools may be mobile, but now often some of the more expensive tools can only be applied in a laboratory setting, and certainly a laboratory-based setting is useful when you wish to control an evaluation; and the possible confounding factors that may apply to that evaluation.

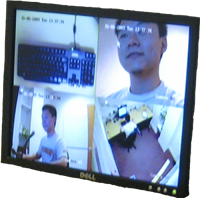

These laboratories, known in the industry as ‘user labs’ or ‘usability labs’, often comprised of three rooms. The first room a user would enter is the reception room where there may be coffee tea and comfy sofas to place the user at ease. There would be a user testing room in which the user and, often, a UXer will sit and conduct the evaluations (this is where the ‘tools’ will be). Finally, there is normally an observation room in which other members of the UX team will observe the evaluations in progress. In some cases, only the user will be present in the user testing room, and only the UX specialists will be present in the observation room5 (see Figure: User Observation).

As we have seen, there are many techniques in the UX specialists arsenal for investigating user behaviour, however, four of the most common listed below:

Performance Measures. Measuring performance is one of the most used techniques for assessing and evaluating interaction. The rationale is that if the task is completed faster than it was before the interactive component was either altered or created when the Interface design must be better as an enhancement has occurred. Common performance measures include: the time required by the user to complete a task; the time spent navigating the interface; the number of incorrect choices or errors created; the number of jobs completed, either correctly or incorrectly; the number of observations of user frustration (see facial expressions below); and finally the frequency of interface components or behaviour that is never used. While performance measures are the most used and most easy to describe to non-specialist audiences, there are some problems that can be introduced at the time the study is created. Indeed, it is often very easy to introduce bias into a set of tasks such that the desired outcome will always be the outcome that performs best. As a UX specialist, you must be especially careful when designing your studies to make sure that this is not the case.

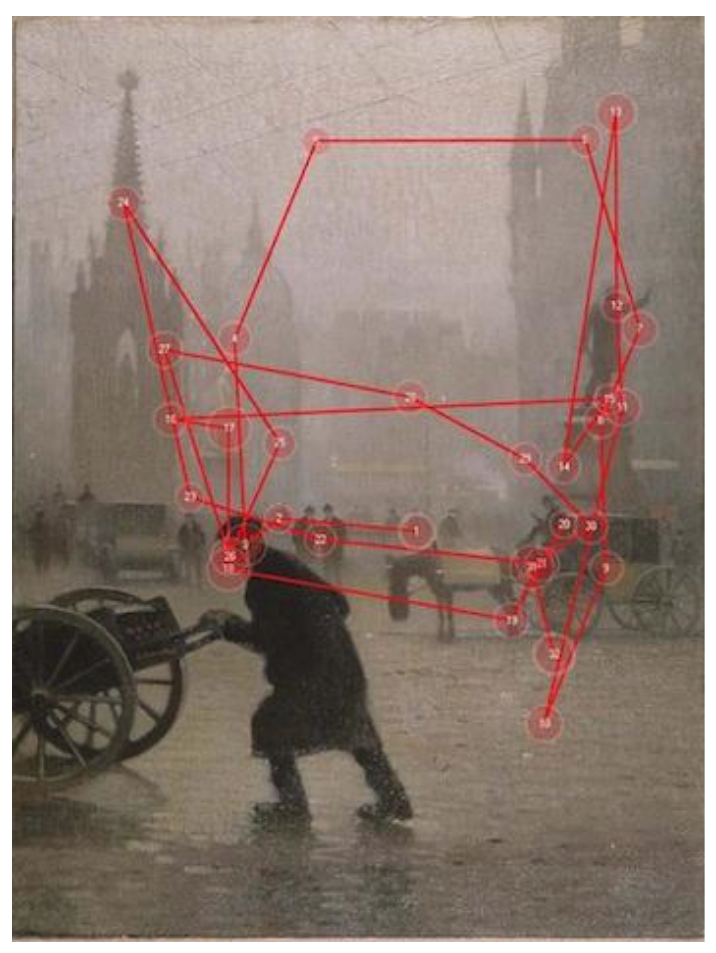

Eye Tracking. Eye tracking technologies are now increasingly used in studies that analyse the user behaviour in a Web search or to reveal possible usability and accessibility problems. Simply, while reading, looking at a scene or searching for a component, the eye does not move smoothly over the visual field, but it makes continuous movements called saccades and between the saccades, our eyes remain relatively still during fixations for about 200-300 ms. A sequence of saccades provides the scanpath (for example see Figure: Eye-Tracking Gaze Plot Example) that the eye follows while looking. Fixations follow the saccades and are the periods that the eye is relatively immobile indicating where it pays more attention, hence, the component that is viewed. Mostly used for usability evaluations we can see their application in determining specific scanpaths about each interface component is highly useful. If each design is associated with a scanpath and fixation points, feedback can be provided for enhancing the design. However, as technology has continued to evolve, applications where an understanding of human perception, attention, search, tracking and decision making are becoming increasingly important. This is because eye movements are driven both by properties of the visual world and processes in a person’s mind. Indeed, tracking eye movements has now become a valuable way of understanding how people allocate their visual attention.

Facial Expression. There are many implicit cues in user behaviour which are difficult to measure by conventional means such as eye tracking or user performance. One way of capturing some of these implicit aspects is by understanding that most users will show these implicit behaviours, such as happiness or frustration, by their facial expressions. Techniques, therefore, exist in which the expression of the user is recorded via a standard computer camera, where each task is timed, and the time of the facial expression is then matched to the task being undertaken at that time. In this way, the specialist can collect a wealth of implicit information concerning the quality of the user experience, if not the participants performance. Again, the UX specialist should be careful to make sure their study is designed correctly and that the analysis of the facial expressions captured in the evaluation is as accurate as possible. Indeed, as we have said before it may be useful to present these expressions, for categorisation, to a disinterested party as a confirmatory step; remember, this is the best way of enhancing the validity of the evaluation when interpretation by the evaluator is required.

Biofeedback and Affective Measures [Picard, 1997]. As with facial expressions, biofeedback is as implicit evaluation process that involves measuring a participants quantifiable bodily functions such as blood pressure, heart rate, skin temperature, sweat gland activity, and muscle tension, recording the information for later analysis. Within the UX domain the most often used biofeedback measurement is Galvanic Skin Response (see Figure: Galvanic Skin Response) which is a measure of the electrical resistance of the skin; this being a good indicator of the participants stress levels. Also, more simplistic by a feedback mechanism such as heart rate and skin temperature can be used in a non-invasive manner to also ascertain the levels of comfort, excitement, or the stress of a participant. Most biofeedback measurements must be analysed in the context of the individual user in a relative format, so, therefore, increases from the baseline recorded when the user is relaxed and under normal conditions are more important than absolute measurements. One final thing to note for the UX specialist is that undisputed scientific evaluation into the possible application of biofeedback is lacking. This is not such a problem for evaluation and analysis but does indicate the immaturity of this kind of technique.

As a UX specialist you are being asked to perform these kinds of experiments and evaluations for some perceived gain. By conforming as closely as possible to the scientific principles of impartiality the evaluation methodologies and preterite tools, you will be able to maximise these gains, and exhibit a high degree of professionalism in what is often a practical engineering setting. Indeed, as we shall see, pushing a bad interaction design to market will only necessitate a more costly redesign at a later date.

Caveat – Experimental Methods

You may have noticed that I’ve not mentioned any tightly controlled task based trials that measure performance directly - and mostly in laboratory-based settings. These kinds of tests are normally used in research and validation of human performance for critical systems or in ‘hard-core’ usability / HCI trials. I’ve steered away from these because in everyday UX you won’t need to use them, and because we only have a limited time in which to cover UX, and these are not – in my opinion – primary to this domain; but rather human factors, ergonomics, cognitive science, and experimental psychology.

Laboratory-based evaluation using experimental methods has been mainly adopted within the human sciences by experimental or cognitive psychologists requiring similar empirical confirmations as their natural science counterparts. In this case, it is seen that the rigorous and formalised testing of participants can only occur in a controlled laboratory setting. While this is the major strength of laboratory-based evaluation, it is also acknowledged to be a possible problem in that the laboratory is not a naturalistic setting. In turn, the negative aspects are accentuated even beyond that of the survey questionnaire. However, in some cases, the UX specialist has little choice in performing laboratory experimentation because the quantifiable richness and rigour of the data produced is not available from any other source. The power of the arguments created from experimental work is often too strong to ignore, and this is why you will find that when only one opportunity for evaluation exists, the UX specialist will most naturally choose a laboratory-based experimental method; in some ways returning to their computer science / engineering roots.

There are some increasingly understood aspects of laboratory-based work that may be problematic:

- Experimenter Bias: The experimenter my bias the laboratory work via aspects such as the guinea pig effect or role bias;

- Obtrusive Observation: The act of observation changes the observed in some way.;

- Not Longitudinal: And so do not represent users changing states over time and experience; and therefore,

- Not Ecologically Valid: In that the results are only valid in the laboratory and not in the real world.

Further definitive aspects of laboratory-based work are the emphasis placed upon control and validity. Aspects of both can be seen at various points throughout both quantitative and qualitative methods however the focus is far more acute in laboratory-based experimental evaluation. This means that various methods for designing and controlling laboratory-based experimental work have evolved both in psychology and in medicine concerning clinical trials, and we have already covered this to some extent. The key aspect of laboratory-based evaluation is the concept of internal and external validity. External validity refers to the degree to which we can generalise the results of the study to other subjects, conditions, times, and places. While internal validity, is specifically focused on the validity of the experiment as it is carried out and the results that derive from the sample. Remember these terms as we’ll be looking at them in more detail), but for now, if you’d like more information on more experimental methods take an initial look at Graziano and Raulin [Graziano and Raulin, 2010].

14.5 Summary

In summary then, we can see that evaluation methodologies range from the very deep qualitative work undertaken by anthropologists, often resulting in an ethnography, through the broad quantitative work undertaken by social scientists, to the observational empirical work of the experimental or cognitive psychologist. Into this mix comes the interdisciplinary aspects of user experience based in software evaluation and design, and in the form of walk-throughs and think aloud protocols. In all cases, there is a need for a combinatorial approach to evaluation design if an accurate view of the user, and their interaction requirements and experiences, are to be formulated. The value of these aspects of the entire software design cannot be underestimated, without them the user experience cannot be assessed, and a bad user experience will directly affect the approval, and, therefore, sales, of the product under investigation. It’s also not all about participants and numbers, remember, Facebook did UX testing For Facebook Home (With Fewer Than 60 People), 6. However, UX is not solely focused on the interface. Indeed, aspects of the interaction enable us to formulate a scientific perspective and enables us to understand more about the behaviour, cognition, and perception of the user, as opposed to purely focusing on changes to the interface; in this way, UX evaluation methodologies have both practical and scientific outcomes. While I would not suggest that the evaluation methodologies discussed here can be applied in every setting, the UX specialist should attempt to create evaluations that can be undertaken in as near perfect conditions as possible.

So what does all this mean, well ‘methods maketh the discipline’, and I’d say that UX has some nice native methods in use with some others pulled in from other more traditional product marketing domains spliced up with advertising metrics. Importantly, the most interesting for me are HEART+PULSE, which together represent some very innovative thinking that – with minor mods – can be directly applied from UX back to the wider Human Factors CS domain.

14.5.1 Optional Further Reading

- [M. Agar.] The professional stranger: an informal introduction to ethnography. Academic Press, San Diego, 2nd ed edition, 1996.

- [A. Bryman.] Social research methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 3rd ed edition, 2008.

- [A. M. Graziano] and M. L. Raulin. Research methods: a process of inquiry. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 7th ed edition, 2010.

- [J. Lazar,] J. H. Feng, and H. Hochheiser. Research methods in human-computer interaction. Wiley, Chichester, West Sussex, U.K., 2010.

- [J. Van Maanen.] Tales of the field: on writing ethnography. Chicago guides to writing, editing, and publishing. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2nd ed edition, 2011.

- [R. W. Picard.] Affective computing. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1997.

- [T. Tullis] and B. Albert. Measuring the user experience: collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. The Morgan Kaufmann interactive technologies series. Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann, Amsterdam, 2008.

15. Human-in-the-Loop Systems and Digital Phenotyping

Systems simulations were a mix of hardware and digital simulations of every—and all aspects of—an Apollo mission which included man-in-the-loop simulations, making sure that a complete mission from start to finish would behave exactly as expected.

– - Margaret H. Hamilton (1965) NASA.

In the bad old days, computer systems were highly inefficient took huge amounts of resources and were not user friendly. Indeed, the head of IBM through the 50s said that he could only see the need for two computers in the world. Obviously, that was incorrect and as time has progressed, users became more important and we became more aware of the fact that humans were an integral part of the system. And so human computer interaction and therefore user experience were created. As part of this, the idea that humans in the loop would be a necessary part of a computer system was not considered until the various Apollo missions whereby human interaction with the system, indeed control of the system became important. Indeed, we may think of it as human middleware became more important, especially with computer systems flying or at least controlling complex mechanical ones.

There is an accessibility saying: ‘nothing about us without us’ and we consider that this should be extended to the human and to the user such that users are integrated into most aspects of the build lifecycle. After all, the human will be controlling the system and even in terms of intelligence systems, artificial/hybrid intelligence and machine learning, have shown to benefit from human input.

Indeed, humanistic artificial intelligence are becoming increasingly more important with most large scale computational organisations. Acknowledging this fact and having large departments which are tailored to this kind of development so for all software engineering and development the human should be considered from the outset and the humans, control actions should also be factors when designing systems which wrap around the user.

15.1 Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Systems

Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) systems are a collaborative approach that combines the capabilities of both humans and machines in a loop or iterative process. It involves the interaction and collaboration between human experts or operators and automated systems or algorithms to achieve a desired outcome. In a HITL system, humans are actively involved in various stages of the decision-making process, providing input, feedback, and guidance to the automated systems. The automated systems, on the other hand, assist humans by performing tasks that can be automated, analyzing large amounts of data, or making predictions based on complex algorithms.

The purpose of HITL systems is to leverage the strengths of both humans and machines. Humans bring their domain expertise, intuition, and contextual understanding, while machines offer computational power, speed, and the ability to process vast amounts of data. By combining these capabilities, HITL systems aim to improve accuracy, efficiency, and decision-making in various domains, such as healthcare, customer service, autonomous vehicles, and cybersecurity.

HITL systems often involve an iterative process, where humans provide initial input or guidance, machines generate outputs or suggestions, and humans review, validate, or modify those outputs. This iterative feedback loop allows for continuous improvement and adaptation, with humans refining the system’s performance and the system enhancing human capabilities. Overall, HITL systems enable the development of more robust, reliable, and trustworthy solutions by harnessing the power of human intelligence and machine capabilities in a symbiotic relationship.

HITL systems have been utilized for a long time, although the term itself may have gained prominence in recent years. The concept of involving humans in decision-making processes alongside automated systems has been present in various fields and industries for decades. One early example of HITL systems is found in aviation. Pilots have been working in collaboration with autopilot systems for many years, where they oversee and intervene when necessary, ensuring the safety and efficiency of flight operations. This demonstrates the integration of human expertise with automated systems.

NASA has embraced the concept of HITL systems across various aspects of its operations, including space exploration, mission control, and scientific research. Here are a few examples of how NASA has adopted HITL approaches. Human space exploration missions, such as those to the International Space Station (ISS) and beyond, heavily rely on HITL systems. Astronauts play a critical role in decision-making, performing experiments, and conducting repairs or maintenance tasks during their missions. While automation is present, human presence and decision-making capabilities are essential for handling unforeseen situations and ensuring mission success.

NASA’s mission control centres, such as the Johnson Space Center’s Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, employ HITL systems to monitor and manage space missions. Teams of experts, including flight directors, engineers, and scientists, collaborate with astronauts to provide real-time support, make critical decisions, and troubleshoot issues during missions. NASA utilizes robotic systems in space exploration, such as the Mars rovers (e.g., Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance). While these robots operate autonomously to some extent, human operators on Earth are actively involved in planning, commanding, and interpreting the data collected by the rovers. Humans in mission control provide guidance, analyse results, and adjust mission objectives based on discoveries made by the robotic systems.

HITL systems are prevalent in data analysis and scientific research conducted by NASA. Scientists and researchers work alongside machine learning algorithms and data processing systems to analyse large volumes of space-related data, such as satellite imagery, telescope observations, and planetary data. Human expertise is crucial for interpreting results, identifying patterns, and making scientific discoveries.

Overall, HITL approaches are integrated into various aspects of NASA’s operations, where human expertise is combined with automated systems to achieve mission objectives, ensure astronaut safety, and advance scientific knowledge in space exploration.

In the field of computer science and artificial intelligence, the idea of HITL systems has been explored since the early days of AI research. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, researchers were already investigating human-computer interaction and the combination of human intelligence with machine processing power. More recently, with advancements in machine learning, data analytics, and robotics, HITL systems have gained increased attention. They have been applied in various domains such as healthcare, where clinicians work alongside diagnostic algorithms to improve disease detection, treatment planning, and patient care. Additionally, HITL systems have become essential in the development and training of AI models. Human involvement is crucial for labelling and annotating training data, evaluating model performance, and ensuring ethical considerations are taken into account. While the exact introduction of HITL systems cannot be pinpointed to a specific date or event, their evolution and adoption have been shaped by the continuous advancements in technology and the recognition of the value of human expertise in conjunction with automated systems.

15.2 Digital Phenotyping

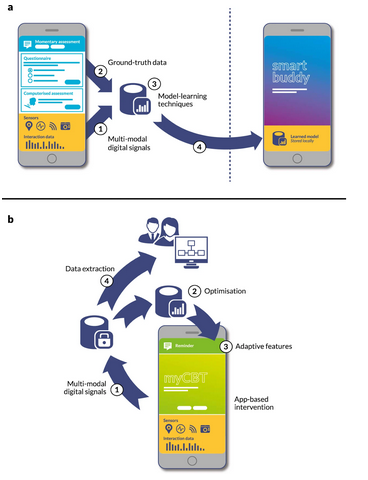

Digital Phenotyping (DP) can be seen as an extension (or at least has a very strong relationship to) HITL systems, in that the human in DP systems is carrying around a mobile device / wearable / or the like and their behaviour in both the real-world and in digital services. This behaviour is monitored and the collected data is used to make inferences about their behaviour.

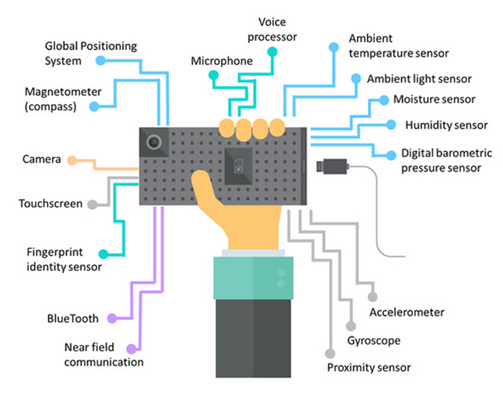

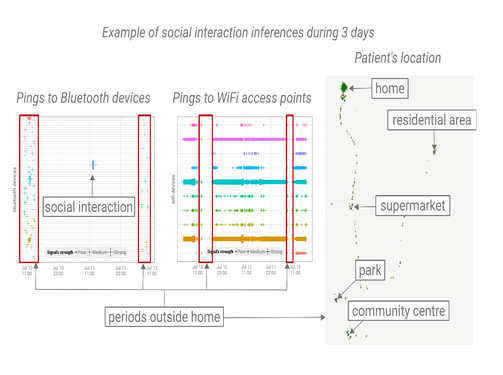

Defined by Jukka-Pekka Onnela in 2015, but undertaken for over a decade before it was named, DP utilises digital technologies such as smartphones, wearable devices, and social media platforms to collect and analyse data on human behaviour and psychological states. This approach is used to monitor, measure, and analyse various aspects of human behaviour, including sleep patterns, physical activity, social interaction, and emotional states. And uses sensors embedded in smartphones and wearables to track various physiological and environmental parameters, such as heart rate, breathing rate, and temperature, as well as factors like location, movement, and interaction with the device. The data collected is then analysed using machine learning algorithms to generate insights into an individual’s behaviour, including patterns of activity, stress levels, mental health, and well-being, and sleep quality. Roughly DP proceeds by:

- Data Collection: Digital phenotyping relies on the collection of data from individuals using their smartphones, wearables, or other digital devices. This data can include GPS location, accelerometer and gyroscope readings, screen interaction patterns, call and text logs, app usage statistics, social media posts, and more. Sensors within the devices capture data related to movement, activity, and contextual information.

- Data Processing and Feature Extraction: Once the data is collected, it undergoes processing and feature extraction. This involves converting the raw data into meaningful features or variables that represent specific behavioural or physiological aspects. For example, data from accelerometer readings can be transformed into activity levels or sleep quality indicators.

- Machine Learning and Pattern Recognition: Digital phenotyping employs machine learning and pattern recognition techniques to analyse the extracted features and identify patterns, trends, or anomalies. Algorithms are trained on labelled data to recognize specific behavioural patterns or indicators related to mental health, cognitive function, or physical well-being.

- Behaviour Modelling and Prediction: By analysing the collected data and applying machine learning models, digital phenotyping can develop behavioural models and predictive algorithms. These models can identify patterns and correlations between digital data and specific outcomes, such as predicting depressive episodes, detecting stress levels, or assessing cognitive performance.

- Continuous Monitoring and Feedback: Digital phenotyping allows for continuous monitoring and tracking of individuals’ behaviours and mental states over time. The data collected can provide real-time insights into changes in behaviour or well-being, enabling early intervention or personalized feedback.

- Integration with Clinical and Research Applications: The insights generated through digital phenotyping can be integrated into clinical settings or research studies. Mental health professionals can use the data to inform treatment decisions, monitor patient progress, or identify potential relapses. Researchers can leverage the data for population-level studies, understanding disease patterns, or evaluating the efficacy of interventions.

It’s important to note that digital phenotyping raises ethical concerns regarding privacy, data security, and informed consent. Safeguards must be in place to protect individuals’ privacy and ensure transparent and responsible use of the collected data.

DP as a term is evolved from the term ‘genotype’ which is the part of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of any individual, which determines one of its characteristics (phenotype). While phenotype is the term used in genetics for the composite observable characteristics or traits of an organism. Behavioural phenotypes include cognitive, personality, and behavioural patterns. And the interaction or interactions with the environment. Therefore digital phenotyping implies monitoring; a moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices in particular smartphones.

The data can be divided into two subgroups, called active data and passive data, where the former refers to data that requires active input from the users to be generated, whereas passive data, such as sensor data and phone usage patterns, are collected without requiring any active participation from the user. We might also equate Passive Monitoring / Sensing to Unobtrusive Monitoring and Active Monitoring / Sensing to Obtrusive Monitoring.

DP conventionally has small participant numbers however the data collected is the key and when you’re collecting ~750,000 records/person/day adaption and personalisation to a user is critical! We can think of Data as the ‘Population’ where small N becomes big N, in this case, DP supports personalised data analysis. Generalized Estimating Equations and Generalized Linear Mixed Models create a population-based model instead of a personalised one however, personal models are however needed in many complex applications. Machine and Deep Learning algorithms don’t prioritise clinical knowledge but rather structure of the data and assume the distribution of the training set is static, but human behaviour is not and often requires tuning, this requires expertise which in practice would not be available for each patient.

Digital phenotyping has many potential applications in healthcare and mental health research. For example, it could be used to monitor and manage chronic conditions such as diabetes or to identify early signs of mental health issues such as depression or anxiety. It could also be used to provide personalized interventions and support for individuals based on their unique patterns of behaviour and psychological state. However, DP has diverse application domains across mental health, and behaviour monitoring among others:

- Mental Health Monitoring: Digital phenotyping enables the continuous monitoring of individuals’ mental health by analysing digital data such as smartphone usage, social media activity, and communication patterns. It can help detect early signs of mental health disorders, track symptoms, and monitor treatment progress.

- Mood and Stress Management: Digital phenotyping can assess and track individuals’ mood states and stress levels by analysing behavioural patterns, including activity levels, sleep quality, communication patterns, and social media content. It can provide insights into triggers and patterns related to mood changes and help individuals manage stress more effectively.

- Cognitive Function Assessment: By analysing smartphone usage patterns, digital phenotyping can provide insights into individuals’ cognitive function, attention, and memory. It can help assess cognitive impairments, monitor cognitive changes over time, and provide personalized interventions or reminders.

- Physical Health Monitoring: Digital phenotyping can be used to monitor individuals’ physical health by analysing data from wearable devices, such as heart rate, sleep patterns, and activity levels. It can track physical activity, sleep quality, and identify deviations that may indicate health issues or support healthy behaviour change.

- Personalized Interventions and Treatment: Digital phenotyping insights can be used to deliver personalized interventions, recommendations, or treatment plans. By understanding individuals’ behaviours, triggers, and context, interventions can be tailored to their specific needs and preferences, enhancing treatment outcomes.

- Population Health Studies: Digital phenotyping can be applied in large-scale population health studies to understand disease patterns, identify risk factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. By analysing aggregated and anonymized digital data, researchers can gain insights into population-level health trends and inform public health strategies.

- Behaviour Change and Wellness Promotion: Digital phenotyping can support behaviour change interventions by providing real-time feedback, personalized recommendations, and tracking progress towards health and wellness goals. It can motivate individuals to adopt healthier behaviours and sustain positive changes.

As technology advances and our understanding of human behaviour and health improves, digital phenotyping is likely to find further applications in various fields related to well-being, healthcare, and personalized interventions.

15.2.1 Can you build a Digital Twin using Digital Phenotyping?

While Digital twins and digital phenotyping are related concepts in the realm of technology and data-driven analysis, but they focus on different aspects and applications.

Digital twins are virtual replicas of physical objects, systems, or processes. They are used to monitor, analyse, and simulate the behaviour of their real-world counterparts. Digital twins are often associated with industrial applications, such as manufacturing, energy, and healthcare, where they help optimize operations, predict maintenance needs, and improve efficiency. They involve real-time data integration, simulation, and visualization to provide insights and predictions about the physical entity they represent. Digital twins are more about replicating the entire behaviour of a physical entity in a digital environment. On the other-hand, Digital phenotyping focuses on the collection and analysis of data related to an individual’s behaviour, activities, and physiological responses using digital devices. It is often used in healthcare and psychology to monitor mental and physical health, track disease progression, and understand behavioural patterns. Digital phenotyping involves the use of smartphones, wearables, and other digital sensors to gather data like movement, sleep patterns, communication style, and more. The goal of digital phenotyping is to gain insights into an individual’s health and well-being by analysing patterns and changes in their digital behaviour.

This said, it is possible to incorporate digital phenotyping techniques into the development and enhancement of a digital twin, which are in many ways complimentary. By integrating data collected through digital phenotyping methods, you can create a more accurate and comprehensive representation of the physical entity within the digital twin environment.

Using digital devices such as smartphones, wearables, and other sensors to collect behavioural and physiological data from the physical entity you want to model in your digital twin. This could include data on movement, activity levels, sleep patterns, heart rate, communication patterns, and more. Then integrate the digital phenotyping data with the data streams from other sources that contribute to your digital twin’s functionality. For instance, if you’re creating a digital twin of a human body for healthcare purposes, you might combine phenotypic data with medical records, genetic information, and environmental data. Incorporate the collected data into the digital twin’s model. Depending on the complexity of your digital twin, this could involve refining the simulation algorithms to better mimic the behaviour of the physical entity based on the behavioural and physiological data you’ve collected. Analyse the digital phenotyping data to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies in the behaviour of the physical entity. This analysis can inform the simulation algorithms and contribute to a more accurate representation within the digital twin. Use the integrated data to make predictions and gain insights. For example, if your digital twin represents a person’s health, you could predict potential health issues based on changes in behavioural patterns and physiological data. Continuously update the digital twin with new data from digital phenotyping to ensure that the virtual representation stays aligned with the real-world counterpart. This real-time monitoring can help detect changes and provide early warnings for potential issues. Implement a feedback loop where insights and predictions generated by the digital twin can influence how data is collected through digital phenotyping. This can help optimize the data collection process and improve the accuracy of both the digital twin and the phenotyping analysis.

By combining digital phenotyping with the concept of a digital twin, you can create a more dynamic and accurate representation of a physical entity, enabling better insights, predictions, and decision-making in various fields such as healthcare, sports science, and more. You can skip backwards to understand how digital twins relate to requirements elicitation if you missed this.

15.3 Summary

Digital phenotyping and HITL systems are related concepts that can complement each other in various ways. Digital phenotyping relies on the collection and analysis of digital data from various sources such as smartphones, wearables, and sensors. HITL systems can play a role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the collected data. Humans can validate and verify the collected data, identify errors or inconsistencies, and provide feedback to improve the quality of the data used in digital phenotyping algorithms. HITL systems can contribute to the development and validation of digital phenotyping algorithms. Human experts, such as clinicians or researchers, can provide their expertise and domain knowledge to guide the development of algorithms that capture meaningful behavioural or health-related patterns. Humans can also participate in the evaluation and validation of the algorithms, providing insights and judgments to assess their performance and effectiveness.

Digital phenotyping algorithms generate insights and predictions based on the analysis of collected data. HITL systems can assist in the interpretation and contextualization of these results. Human experts can provide a deeper understanding of the implications of the findings, identify potential confounders or biases, and help translate the results into actionable information for healthcare providers, researchers, or individuals. HITL systems enable continuous feedback loops for digital phenotyping. Users or individuals can provide feedback on the insights or predictions generated by digital phenotyping algorithms. This feedback can help refine and improve the algorithms over time, ensuring that the system becomes more accurate, sensitive, and tailored to individual needs. Further, HITL systems play a crucial role in addressing ethical considerations related to digital phenotyping. Humans can ensure that privacy concerns, data security, informed consent, and fairness are appropriately addressed. Human judgment and decision-making can guide the responsible and ethical use of digital phenotyping technologies.

Overall, HITL systems can enhance the reliability, interpretability, and ethical considerations of digital phenotyping. By involving humans in the data collection, algorithm development, interpretation of results, and feedback loops, we can create more robust and responsible digital phenotyping systems that align with user needs, expert knowledge, and ethical standards.

15.3.1 Optional Further Reading

- [Mackay, R. S. (1968).] — Biomedical telemetry. Sensing and transmitting biological information from animals and man.

- [Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D., & Sechrest, L. (1966)] — Unobtrusive measures: Nonreactive research in the social sciences (Vol. 111). Chicago: Rand McNally.

- [Licklider, J. C. R. (1960)] Man-Computer Symbiosis, IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics, volume HFE-1, pages 4-11, March 1960.

- [Onnela, Jukka-Pekka; Rauch, Scott L. (June 2016)] — Harnessing Smartphone-Based Digital Phenotyping to Enhance Behavioral and Mental Health. Neuropsychopharmacology. 41 (7): 1691–1696. doi:10.1038/npp.2016.7. ISSN 0893-133X. PMC 4869063. PMID 26818126.

- [Harald Baumeister (Editor), Christian Montag (Editor) (2019)] — Digital Phenotyping and Mobile Sensing: New Developments in Psychoinformatics (Studies in Neuroscience, Psychology and Behavioral Economics) 1st Edition

- [David Nunes, Jorge Sa Silva, Fernando Boavida (2017)] — A Practical Introduction to Human-in-the-Loop Cyber-Physical Systems (IEEE Press) 1st Edition

16. Evaluation Analysis

You can design and create, and build the most wonderful place in the world. But it takes people to make the dream a reality.

– Walt Disney

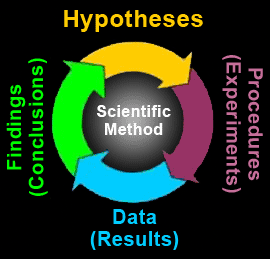

Designing your evaluations is one of the most important aspects of any user experience process. If these evaluations are designed badly you will not be able to apply the correct analysis, and if you cannot apply the correct analysis you will not be able to make any conclusions as to the applicability or success of your interventions at the interface or interactive level [Baggini and Fosl, 2010]. In reality, this means that if this is not done correctly the previous ≈200 pages of this book have been, to a large extent, pointless.