Part V: In Real Life

17. In Real Life

What we do not understand we do not possess

– Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

UX work design espoused by the ‘standard’ textbooks often assume perfection in the process. They assume that there are no limitations on the time required for the work to occur; they assume that there are no limitations on the skills required for the work to occur, and they assume that there are no limitations on the instruments required for the work to occur – to name but three.

17.1 Realistic, Practical, Pragmatic, and Sloppy!

However, we can characterise UX as having many pragmatic limitations such as the knowledge required, weighted against the limitations of time, participants, resources, and skills, along with the practicalities associated with data capture, sampling, and analysis. Further, because domains are often so separated what may seem like a short amount of time to one researcher may seem like an incredibly long amount of time to another. This proves to be an even greater problem in the UX domain where often the work is highly interdisciplinary, and methodologies are used from many different and competing domains [Vogt et al., 2012]. A domain expert from one may feel that time is grossly over exaggerated or under exaggerated based on their experience of their specific domain. Further, it is often assumed that participants and their recruitment will be an easy administrative task while most textbooks admit that some form of remuneration is often required; they certainly expect that all participant recruitment will have taken place before experimentation commences such that the sequence of experimentation can be very linear and well-defined. Participant recruitment on the fly is often not discussed, and the difficulty in soliciting participants while maintaining an accurate sampling, and getting those participants to return for within sampling work is mainly assumed as a given. Also, resources are often taken for granted with textbooks making no suggestion as to how aspects such as instrumentation, financial reward, and experimenter availability should be addressed. Rather it is given that the correct instruments will be available, financial rewards for bursaries for participants and recruitment will be available, and in the case of double or triple blind trials, the requisite number of UXer’s will be on hand to assist in carrying out the work.

In cases where the working domain is interdisciplinary, there is also an implicit assumption that any UX’er can become an expert very quickly at any other research methodology. Indeed, many textbooks present a series of methodologies for the UXer’s consumption and with an expectation that an understanding of the procedure is all that is required for an accurate application of the method. However, different kinds of interdisciplinary research are often very difficult to conduct, and for the best results, which include an understanding of all the pitfalls, the UX’er often needs to perform many of these methodologies before even a basic understanding of the problems and best practices can arise. Indeed, this is one of the reasons I’ve created this chapter; to try and give the novice UX’er a head start in understanding the problems and contentious issues surrounding each of these working methodologies based on my failings and experiences over the last ten years of user experience work in Interaction Analysis and Modelling.

However, before we look more closely at the way things are done ‘in–the–wild’ it is useful to take a look at the textbook methods). Have a look back to rediscover how things should be done in a well–defined world without limitations or practical considerations [Alkin, 2011]; a world which does not allow reality to impinge on the method. In this chapter, we intend to give an overview of the possible trade-offs and limitations based on the real–world situations which often apply. These real–world situations have been experienced by our UX teams in both academic and contract work for third–party organisations (both commercial and non–commercial). Here we describe the kind of limitations that often affect evaluation design, and thereby enable new UX’ers to the field to gain an understand the kinds of decisions and choices that need to be made in different situations, while still enabling a valid scientific outcome to the end results [Gliner et al., 2009].

We have come to a more realistic understanding of the work that is often possible under applied conditions, as opposed to that found in most texts. In reality, these practical considerations centre around our understanding of the knowledge requirements and purpose of the work, the limitations which will always be imposed upon that work, and the availability of skills which are required to accomplish a satisfactory practical outcome. By understanding these aspects more realistically from the outset, the scientific value of the evaluations that are undertaken is much more likely to be maintained. This contrasts with a dogged following of textbooks methodologies which must be changed and modified ‘on–the–fly’ as the situation necessitates in, primarily, a reactionary way as opposed to our proactive methods; based on an expectation of imperfection within the process.

17.2 Expect Imperfection

Designing your evaluation is one of the most important aspects of any piece of UX work, certainly within the human factors domain. A good evaluation design will save time and energy from the outset and as the project proceeds. There is often a tendency to not fully think about the methodology and plan the steps to a suitable outcome from the start. However, this normally turns out to be an unproductive strategy because the methodology is not fully formed, and from the point of view of an ethics committee or grant review, the holes within that methodology suggest that not enough preparatory work has been undertaken. Further, this suggests that the planning and methodology are weak and that the desired outcomes of the work are unlikely to be successful.

Of course, this is the way most texts on the subject of evaluation methodologies and evaluation design justify their methodologies. Textbooks suggest that the UX’er proceed in a well ordered and structured manner; and with good reason. However, this is often not possible due to a number of different and conflicting factors. In some cases it may be because other parts of the software project have not been completed on time, or that human factors work was not included within the planning of the original methodology or software design; engineers notoriously often forget users.

Even if the time for a user study is included, if the project planning is completed by someone without UX experience then it is likely that there will be an underestimate of the time and resources required for proper evaluations. In the case of academic work, this can often happen when the human factors testing and evaluation are added as an afterthought, or when the UX specialist is not consulted from the outset and is only presented with a testing regime into which significant experience in human factors is not being applied.

We will see that design in the real world is characterised mainly by limitations. However, many textbooks on the subject are characterised by assuming a perfect evaluation scenario, which the UX specialist only has to apply for a valid outcome to be forthcoming. In reality, this happens only very rarely or in cases where the UX component has been designed by the specialist who will be responsible for the output. Even then many implicit factors will weigh on the decision as to which evaluation methodologies to use; as opposed to a purely neutral decision based on the best methodology to elicit the knowledge required. These factors are often based around more realistic considerations such as over-familiarity of a particular methodology, the specialists’ competence with the statistical analysis techniques required to support the outcome, and the pre–known outcomes which are preferable to the organisation paying for the evaluation; indeed in some case, user evaluation is just regarded as a ‘box–ticking’ activity to show due diligence. Indeed, there are many implicit assumptions about the kind of knowledge that is required or practicable. These assumptions are often drawn because certain experimental designs and research methodologies or often used in specific domains. It, therefore, becomes a ‘fait accompli’ that certain knowledge, or kinds of knowledge, is favoured beyond others in certain domains because certain research methodologies return that sort of knowledge. In reality, it is often the other way round in that a certain kind of knowledge is required and methodologies to collect that knowledge have evolved and have been developed within of a specific domain which requires this knowledge.

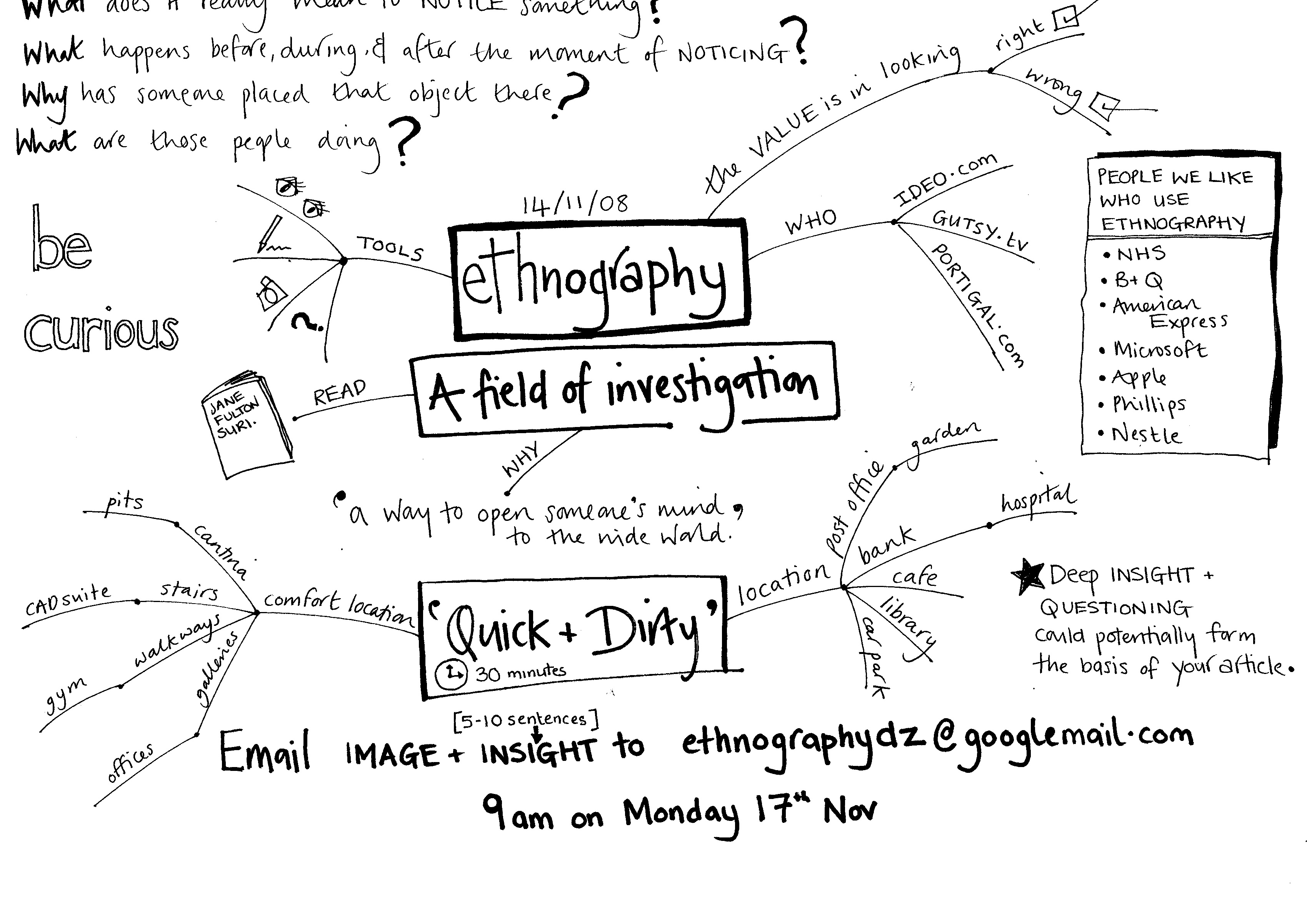

In this case, many assumptions about the kind of knowledge that the reader of a certain textbook will collect or require are already made. For instance, in the anthropological or ethnographic domain, the kind of knowledge required is deep, qualitative, and reasonably specific to an individual or small group of individuals; the premise being that understanding small groups will allow us to extrapolate out to larger populations. This means that the research methodologies which have evolved in this domain are specifically keyed to produce this kind of research, and the experimental design is manipulated to use this kind of research methodologies. If you like, this can be thought of as a kind of ‘domain–group–think’ whereby a domain of enquiry thinks in a certain way and so the experimental design is often tailored to that way of thought (see Figure: Ethnography?). Indeed, in most instances a different design methodology is unlikely to be excepted if it diverges too much from the expected. In this way, we can see that it is very unlikely that an experimental methodology, such as is found in cognitive psychology, would be used as part of an anthropological study even though some of the resultant information may be useful.

17.3 Commissioning Constraints

For the most part, they are two different kinds of evaluation which are available to the UX specialist; these are the formative, and summative evaluation. As we have already seen, formative evaluations occur before a software artefact is developed or a hypothesis is tested; and summative evaluations occur after a software artefact / intervention has been created. These two different kinds of evaluation enable us to do different kinds of UX work. Firstly, a formative evaluation allows us to understand the problem domain, test our understanding of that problem domain, guide our proposed hypotheses, and, therefore, the development of our software. In UX, and within the greater human-computer interaction domain, this formative aspect is sometimes not required. This is because the summative aspect can be applied to a software artefact to enable us to decide if it meets a pre–existing specification (remember ‘Single Group, Post Test’).

In the most basic case, we can assume that our domain understanding of the user experience, in general, will enable us to create a set of summative evaluations which will allow us to decide how well the software meets current best practice. In this case, we cannot run a true experiment because there is no way to compare the improvements which are gained between pre-test and post-tests of the user experience. Besides, this kind of testing does not enable us to say anything more about human behaviour, only that the participant evaluations showed that our software was to some degree beneficial; therefore complying with various human factors specification and testing regimes. In the second case, the summative evaluation can comprise two parts: the first being a pre-test and the second being a post-test in this way we can conform to the true experiment and also gauge the improvement in user experience by measuring the before modification, and after modification, variables. In reality, an experienced UX specialist will understand the real–world limitations of evaluating software in the wild, and in this case, build in a pre–test component as part of the formative evaluation such that hybrid methods are used; maybe an interview or survey followed by a small UX experiment within a laboratory setting: this last: would serve as the pre–test component of the summative experiment.

Textbook approaches to experimental design, and the choice of methodologies, often rely solely on selecting the best methodology for the job at hand. That methodology, as we have seen, assumes a certain knowledge of the application domain, with specifically favoured methodologies becoming popular in different domains. In reality, and certainly within the UX domain, things are not so straightforward. The real–world inflicts many constraints at this point and so unless the design is for academic work, which you have full control over, aspects of the design will be beyond our control. I have found that our lab (commercial user experience services) are often approached by third–party organisations which do not have the usability, and human testing experience that we possess. In this case, there is often no design requirement to use a certain research methodology, but there are limitations of time and budget allocated for the specific work. In this case, we have come to define these commissioning constrains as:

Just–In–Time Constraint. Often commissioners tend to leave aspects of the project planning which they know least about until the end, preferring not to go too deeply into this area because they become worried about their lack of understanding. Therefore, there is a tendency for the UX specialist to be approached just in time for the user testing to begin. This puts incredible pressure on the UX’er to design and instigate testing on a very short notice.

Too–Little–Time Constraint. Extending the ‘Just–In–Time Constraint’, the ‘Too–Little–Time Constraint’ suggests that in most cases, ‘user evaluation’ is all that is included within the project plan and the finer points of understanding how this testing should proceed are neither understood all considered further. In this case, there has not been enough time allocated for post tests or nonlinear aspects of the work which could be run in parallel with other aspects of the project plan. As enough time has not been devoted to these aspects within the plan, testing is likely to fail or at best be very rushed.

Non–Specialist Constraint. There are additional variations of the two constraints previously listed; being those which include a very badly planned user evaluation, usually by a non–specialist, whereby because the planning stage is inflexible to higher-level management a none–scientific experimental evaluation looks like it needs to be considered.

Inadequately Funded Constraint. This constraint comes to the fore when user evaluation seems to be planned reasonably well, but the amount of funding required to accomplish it and participant payment within that funding model are not adequately considered.

Pre–Supposed Outcome Constraint. Planning in the real world often focuses on the achievement of the desired outcome. Indeed, most project planning and business planning revolve around achieving the correct outcome at each stage of the process. Therefore, a manager or engineer planning a piece of work will have the desired outcome in mind, which in reality will not just be a desire, but be a project requirement. In this case, there is an enormous amount of pressure on the UX specialist to deliver this requirement, support by the testing or not.

Implicit Overrun Constraint. Even when there has been enough funding and time allocated to an unplanned user evaluation, it is often accepted that it will be the final stage of the development, and, therefore, the plan is seen to fit into a linear dimension as one of the last parts of the project development. In this case, overruns in other aspects of the work, often considered to be more important than the UX testing, tend to eat into the time available for the linear plan.

Due Diligence Constraint. Normally as a function of the ‘Inadequately Funded Constraint’ and in combination with the ‘Too–Little–Time Constraint’ we see that in some cases the usability study is only an afterthought such that the software engineers can demonstrate due diligence; and in reality expect no more than a cursory ratification of the development. Here we can see that this is very difficult for the web ergonomics specialist to handle because acceptance often implies a Pre–Supposed Outcome. How this is handled, and whether the contract is undertaken by the specialist is a matter of personal choice

UnConstrained Experiment. Finally, there is that rare occasion whereby the work of the UX specialist is understood and respected by the project planner, and indeed, be commissioner of the development. This is often the most rewarding type of work undertaken and in many cases occurs in academia or in research and development work for large corporations whereby UX, human factors, and human behaviour are the central focus of the scientific outcomes which are expected as opposed to a standard software development. We describe this, in the Web Ergonomics Laboratory, as the unconstrained experiment. Here we can bring a well-designed experiment using multiple methodologies and hybrid techniques to bear upon a problem domain using a full range of tools instruments techniques and hypotheses.

These commissioning constraints not only have a direct bearing on the decision as to which UX methodologies to use but also how the experimental design is conducted.

17.4 Information Requirements

Organisations, especially those concerned with research and development, be they research, aca demic, or commercial often approach us with a set of information requirements. These requirements are mainly concerned with understanding aspects of a specific UX domain related directly to the organisation focus. However, these requirements can often be distilled into single line statements about the requirements that the information must fulfil. While the following statements are not an exhaustive set, they are particularly indicative of the real–world objectives which we have encountered:

“What is the general feeling for an area, give us the extent and scope of the problems we face; This is the extent and scope of the domain (as we understand it) confirm this is the case and come up with some ideas as to a solution or more formal testing; This is a specification, test our software to make sure it fulfils the user requirements of this specification; We know the extent and scope of the area, and indeed, have some ideas for solutions to the problems we face, do some informal testing so we are able to quantify which solution will be best; ‘We believe our software fulfils these three well-defined goals, test to make sure we are correct; We feel these problems exist in the domain, rigourously test our hypothesis to find out if we are correct; The system used to be like this before our changes, now it has been upgraded, now test to make sure there is a quantifiable benefit; and This was the state of our knowledge beforehand, we have made these predictions, now must test whether our predictions are correct in a rigourous and quantifiable manner.”

In this case, we can see that different information requirements require different ways of eliciting this information. Certainly, within our laboratory, the information requirements of the study are normally limited by the requirements and constraints of the commissioning organisations. In our case, this is normally research councils, and therefore, we have direct control of the planning process. In this way, most of our work is unconstrained and uses multiple hybrid techniques to gather as rich a dataset as is possible. However, we have also noticed that when commissioned to work for other organisation, we often progress from a very resource light to a very resource heavy, scenario based on the kind of information we feel is required. This normally means that we have five different levels of information elicitation:

Flavour Elicitation. This is the least resource hungry information elicitation process. In this case, we look to understand the related work within the area including standards and best practices; even the UX specialist cannot retain all aspects of accessibility, usability, and ergonomics. We then plan some exploratory studies often based around informal interviews and discussions to scope the extent of the problems we are working on and suggest possible solutions. This work gives a flavour for the problem at hand and allows us to better understand the extent of the domain and where our work should be placed within it.

Ideas Elicitation. Here we wish to firm up our understanding of the scope and extent of the work, and generate some ideas for how we could proceed into both a formal development and some more rigourous work; to uncover just exactly what problems exist. In some cases ideas and flavour can be combined, however for most work generating ideas the specialist would normally have a very strong feeling for the domain, and, therefore, the flavour requirement may not be necessary.

Informal Elicitation. Informal testing enables us to understand if our initial ideas have some traction by allowing as to dynamically create assumptions, predictions, and hypotheses and test these on-the-fly in an informal setting. This setting is normally based around a reasonably rigourous interview, but the number of participants may be reasonably limited and maybe solicited without much reference to demographics or correct user sampling techniques. In this case, we are trying to decide if it is worth increasing our resources and placing more formal studies within the domain which will require much more commitment to the task at hand.

Formal Elicitation. Here we have decided that there is indeed some interesting information to be learnt and have decided that we should devote more resources to finding out and isolating this information. Here we use the previous three kinds of information elicitation to enable us to create and test a set of hypotheses. This conventionally involves formal surveying techniques and questionnaires such that numerical statistical analysis can be achieved. Eventually, however, if these hypotheses become reasonably concrete the testing may be accomplished within a laboratory setting.

Laboratory Elicitation. This is the most resource hungry form of information elicitation and can involve both pre and post–tests as a mature experiment. In some limited scenarios post–testing is sufficient although this means that it cannot be considered a true experiment.

By understanding the information requirements of the commissioning organisation we can create a flexible series of experiments which will enable us to fulfil those requirements; as long as we factor in both the design limitations and the available skills of the researchers.

17.5 Limitations

As well as considering the commissioning and information requirements, many more technical limitations within the UX design must be considered before a realistic programme of work can be embarked upon. In general, there are three factors which limit the effectiveness of a programme of work, these being time, participation, and resources.

17.5.1 Time

Time is a critical factor, not just within the planning and project management of the software process, but also when planning the finer details of the application of the UX methodologies. In reality, you will mostly have a finite and limited time for the entire evaluation. This time limitation can be further sub-divided based on the kinds of tasks that are required; the amount of writing which is undertaken; the amount of reporting and administrative components which make up the design; and the amount of interaction with other stakeholders which will always require more time within any methodology or design phase.

Additional time must also be planned for designs which involve iterative testing of software or other kinds of solutions. Iterative testing and development are one of the most critical aspects of applied empirical work because the results of the user study are a driver for the next iteration of development; such that the final post–test should demonstrate a significant improvement in the ergonomic aspects of the developed software. However, time is required for iterative development, and this means that time allocated for development cannot be used for the testing cycle, likewise development is stalled until the interim report from the iterative evaluation is complete.

The only way to mitigate these factors is to divide the user-facing aspects of the development into sections, testing each section while interweaving development on a different section together such that and efficient parallelisation of the iterative evaluation and development cycle can be accomplished

17.5.2 Participants

Soliciting participants are one of the most intractable limitations in any user-facing evaluations. This is especially the case for niche user groups such as users with disabilities, older users, younger users, and users from certain ethnic or social backgrounds. Recruitment is often difficult and time-consuming, indeed, at the Web Ergonomics Laboratory we expect that the experimental phase will not proceed in orderly chunks but will be distributed over the space of a project based on the difficulties in soliciting users for studies.

There are some things which can mitigate these difficulties, such as bursaries and honorariums, or rewards such as vouchers, chocolates, or being placed into a lottery to win a prize; however, on their own these are often not enough. In reality, the UX’er should form pre–existing relationships, which are strong and reciprocal, with the community organisations which represent these participant groups. Having endorsement from a trusted third party, such as a community or advocacy group, enables the work to be undertaken in a far more efficient manner. Without this endorsement, it is often difficult to recruit participants in the first place, and then entice them to return if further testing is required. In any event, you should make sure your evaluation design includes long periods for recruiting participants.

In the real world this recruitment often occurs as empirical aspects of the research proceeds; in this case participant recruitment and UX, evaluation occurs in parallel as opposed to separate well-delineated chunks. This normally means that participant numbers are limited. It is worth remembering that in user experience we do not have the luxury of participant numbers such as those within the social sciences, clinical medicine, or epidemiology; to name but three. In reality, human factors work is often confined to small user groups and at my laboratory, we would consider ourselves lucky to recruit thirty general participants, or between five and ten from a niche user group. This level of participant recruitment will affect the UX methodologies which you will be able to choose; it also means that your data becomes very valuable and so should be collected in a very rigorous manner, and stored openly. If your data is stored openly, and the data of other UX specialists is likewise openly stored, then data reuse, a perfectly except a way of – certainly isolating problems for a post-test or formative evaluation – can occur

17.5.3 Resources

The final piece of the puzzle is the availability of resources. In this case, we mean both funding arrangements for participant reimbursement, as well as funding for travel to and from site visits for the UX’ers, in addition to the number of UX specialists available. This last part is critical, in that it defines the kind of evaluation work and the rigour that can be accomplished.

With only one UX’er a double–blind or triple–blind trial is not feasible. When we talk about a double–blind trial we mean that the researcher who has designed the evaluation procedure and understands the UX outcomes which would be desirable for the programme of work is not the same person who enacts that methodology with participants. In this way, the desire for a certain specific outcome being implicitly transmitted to participants can be removed. But this means that more resources are required, and these may not be available.

Obviously, the most qualitative piece of work the less likely it is that a double–blind trial will be required. This is because interpretation and an understanding of the domain are key for these kinds of methods. However, the more quantitative or experimental the trial is, the more likely it is that a double–blind or triple–blind method should be used. In the case of a triple–blind methodology the specialist who has designed the work is different to the UXer, who is conducting the data collection, and both are different to the specialist who is performing an analysis of the data, once collected. This means that the statistical analysis of the data collected is not biased towards the desired outcome. However, for human factors work triple–blind trials are often inadvisable because the analysis of data collected from applied work is often nuanced and some level of domain understanding is required.

We can, therefore, see that these three kinds of limitations directly affect the way that research should be planned. It is only with a knowledge and understanding of the time required, the difficulty of participant recruitment, and the constraints on resources exhibited by a particular research team that an experimental design can be created to exhibit a successful experimental outcome.

17.6 Available Skills

The available skills of the specialist are often overlooked, both at the evaluation design stage and when the methodologies are chosen or are about to be undertaken. It is often assumed that the UX’er will have a basic set of research skills which will enable them to, in some way, perform all research tasks. While this may be true in some rare cases, the experience which a UX’er brings to a certain domain of investigation should not be overlooked. Skills, along with the experience of the specialist, are a key factor in understanding the amount of time that a piece of work will take. If the specialist is highly conversant and expert within a certain methodology, then we can assume that the process will be very much faster. However, if the specialist has to learn the skills on–the–job we can see that this may extend the time required for the methodology to be accomplished successfully. Indeed, inexperienced UX’ers, learning new methodologies on–the–job, often means that there is a significant amount of backtracking and redoing of work; as experience is increasingly gained. In this case, we should not think that it is impossible for a UX’er to learn new techniques. However, we should make allowances for the mistakes which will inevitably be made and for the rectification of those mistakes.

17.6.1 Instrumentation

Understanding instrumentation and its availability to the researcher is key when designing experiments. Our experiences, at the Web Ergonomics Laboratory, suggest that instrumentation is often a useful addition to the evaluation design, but it should not obscure the abilities of the UX’er to come to a suitable and accurate outcome if the instrumentation is not available. For instance, when we started the laboratory ten years ago, all our work was conducted with a pen, paper, and questionnaires. This level of instrumentation enabled us to observe users performing tasks in both naturalistic settings and quantitative and qualitative ones. Indeed, in some cases, it also enabled us to understand user behaviour in laboratory settings. However, we found that a screen recorder with the ability to log information and facilities to accurately measure users’ behaviour – and record it – made this job increasingly simple. We then acquired video and audio facilities to record all user movements and activity within a laboratory setting; and augmented this with the ability to eye–track users, thereby enabling us to make some connection between the cognition of the user and their interaction with the interface. Finally, many biofeedback devices enabled us to monitor different aspects of the user’s state while interacting with specific interfaces.

In this way, instrumentation can be seen as useful but by no means a bar to accomplishing good UX work. However, in all cases, it took us some evaluation attempts to fully understand and become proficient in the instruments that we were using. In this case, the UX’er, who wishes to use more complex instruments, should understand that this is possible and often advisable but that the data collected from these instruments will initially be inaccurate, and the work will need repeating as the UX’er becomes more familiar with the device.

17.6.2 Collection

Data collection is another aspect of the evaluation methodology which may cause problems. As we have previously seen, different UX methodologies pre–suppose a different training because they come from specific single disciplinary domains. Therefore, understanding the data collection necessities one UX methodology, which may not be second nature to a UX’er, who is a highly trained expert in a methodology from a different domain. For instance it is often initially difficult for qualitative investigators from, say, the social sciences, to fully understand the rationale for data collection and the qualitative aspects of data collection from, say, anthropological ethnography. Likewise, in the UX domain we see a very high level of interdisciplinary evaluation methodologies being used, but because the training of the UX’ers has often occurred within a single domain it will take time for their mindset to alter such that they understand the new methodologies and the data collection requirements inherent within those methodologies.

17.6.3 Analysis

Finally, data analysis is one of the key and thorny issues which surrounds UX work. In many cases, the quality of the data analysis is key to understanding the outcomes of the work, whether that data be collected via complex instrumentation or simple pad, pen and observation. In either case, understanding how to analyse the data and what that analysis may tell us is key to an accurate outcome.

In most cases we can understand the qualitative aspects although for a more rigorous quantitative outcome we should also transcribe each script such that we can understand repeating concepts and terms which arise between participants pointing to a more general understanding of problems or solutions within the specific evaluation. However, the key aspect to analysis is statistics. In most cases statistical analysis used incorrectly can prove to be a tool for inaccuracy, miss–understandings, and miss–information. However, used correctly, statistics can tell a significant amount about the UX domain. Statistical analysis can run from the quite simplistic to the quite complicated, however, as soon as the term ‘statistics’ is mentioned most researchers become understandably wary . This is mainly because the possibility for the introduction of errors are increased and the concepts which surround statistical analysis are perceived as being complex; and in some cases a ‘dark–art’.

As we have seen, basic statistical tasks are nothing to worry about; these range from statistical test which allows us to describe the internal consistency of the data themselves without making any generalisations over a wider group of users; to inferential statistics which allow us to extrapolate some meaning from a certain set of data and extend it over a larger population than the sample from which it was extracted. Choosing the right statistics for the job is key, and once that choice is made the automated software is sophisticated enough to do with the rest. As long as the UX’er understands those statistical outcomes there is nothing to fear and an accurate analysis, with a high degree of certainty, can be achieved.

We can see then, that if the evaluation designer does not take into account the experiences of each UX’er within the team, and their ability to contribute to different aspects of the skills required, then the evaluation can become badly flawed in terms of time and scientific outcome. By understanding the possible risks at the design phase, and by mitigating those risks usually by increasing the time allowed for the work, and in some cases adding a training element to the design, successful and accurate UX evaluation outcomes can be achieved.

17.7 Optimism

We can see then, that expecting uncertainty and variability within the plan is not only advisable but the key to maintaining good user experience outcomes. Even if the project plan and the other members of the team do not take this viewpoint, you – as a user experience professional – should. Indeed, there are many salutary lessons we can learn from other business and engineering domains. However, some of the best advice comes from Frederick Brooks’ experience on the IBM 360, which he generalises in his book ‘The Mythical Man Month’ [Brooks, 1995]; and I believe centres mainly around optimism.

There are of course many opposing views to the generalisations Brooks sets out, as well as changes by the author after 20 years of retrospective work; however, in my opinion, the bones of the work are still valid and in some cases the retrospective reviews or incorrect1.

This said, the Mythical Man Month is most famous for stating Brooks’ Law which, as he says, is oversimplified but states that ‘Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later’. However, while this is useful in the user experience domain especially when we are trying to address commissioning constraints (for constraints, read errors) such as the ‘Just–In–Time Constraint’ and the ‘Too–Little–Time Constraint’ it should not be our main focus. One key aspect that most commentators or experts failed to address – and which Fred Brooks gets right – is that computer scientists, developers, software engineers, and user experience specialist related to these technical domains are mostly optimistic.

This optimism is one of their key strengths; they expect to code better, think most problems are soluble with enough technology and code, create systems which are often useful, and focus on bugs which they believe can all be removed. But this optimism can often be a hindrance when it comes to planning a project and understanding when aspects of the project will be completed; and to what level of maturity those answers, generated from evaluations, are at. In effect we want to believe the system is good because we’re optimistic; even when the system is bad, or the process will over run, or all bugs will not be found, and not all problems have solutions amenable to code / device development.

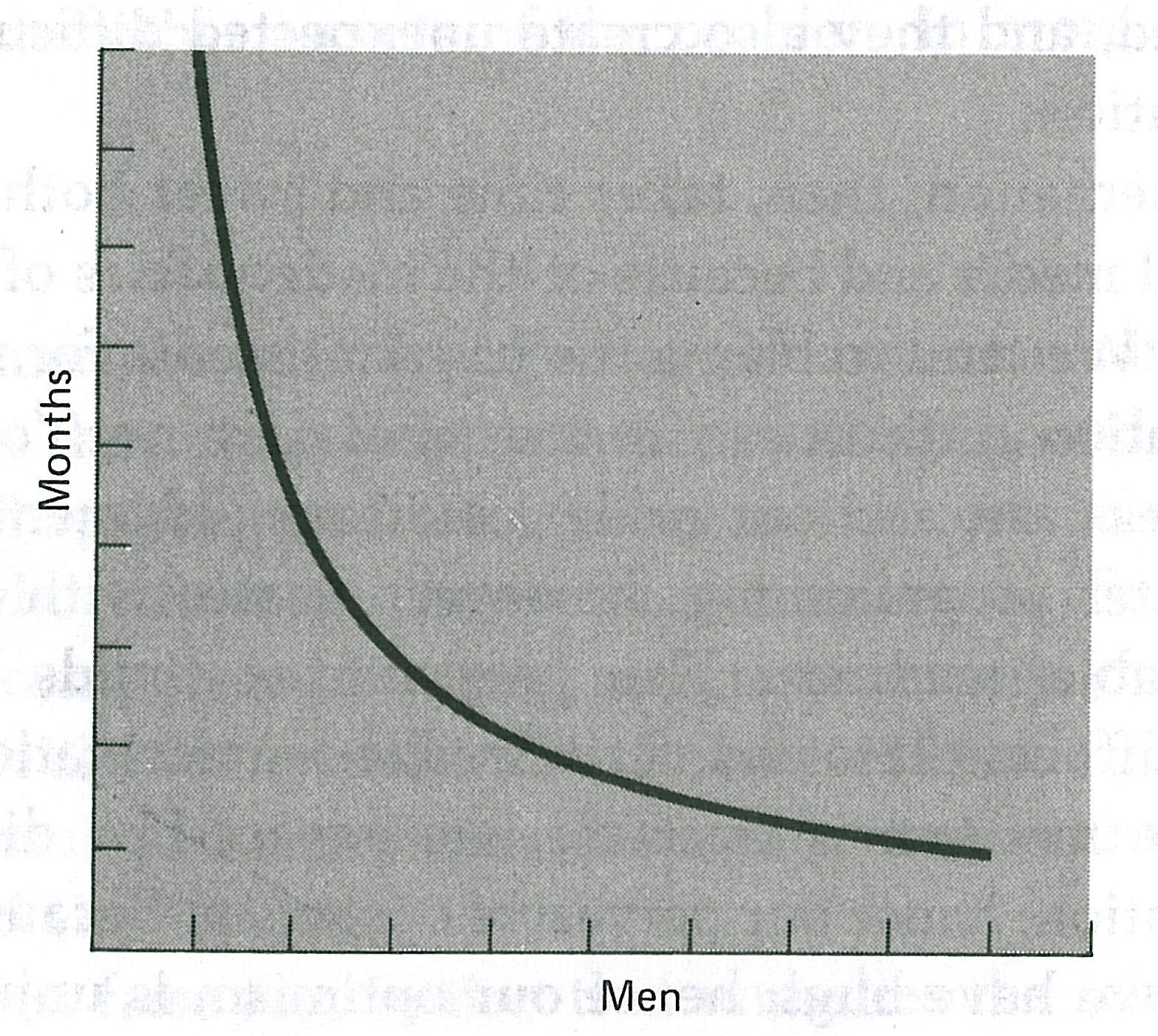

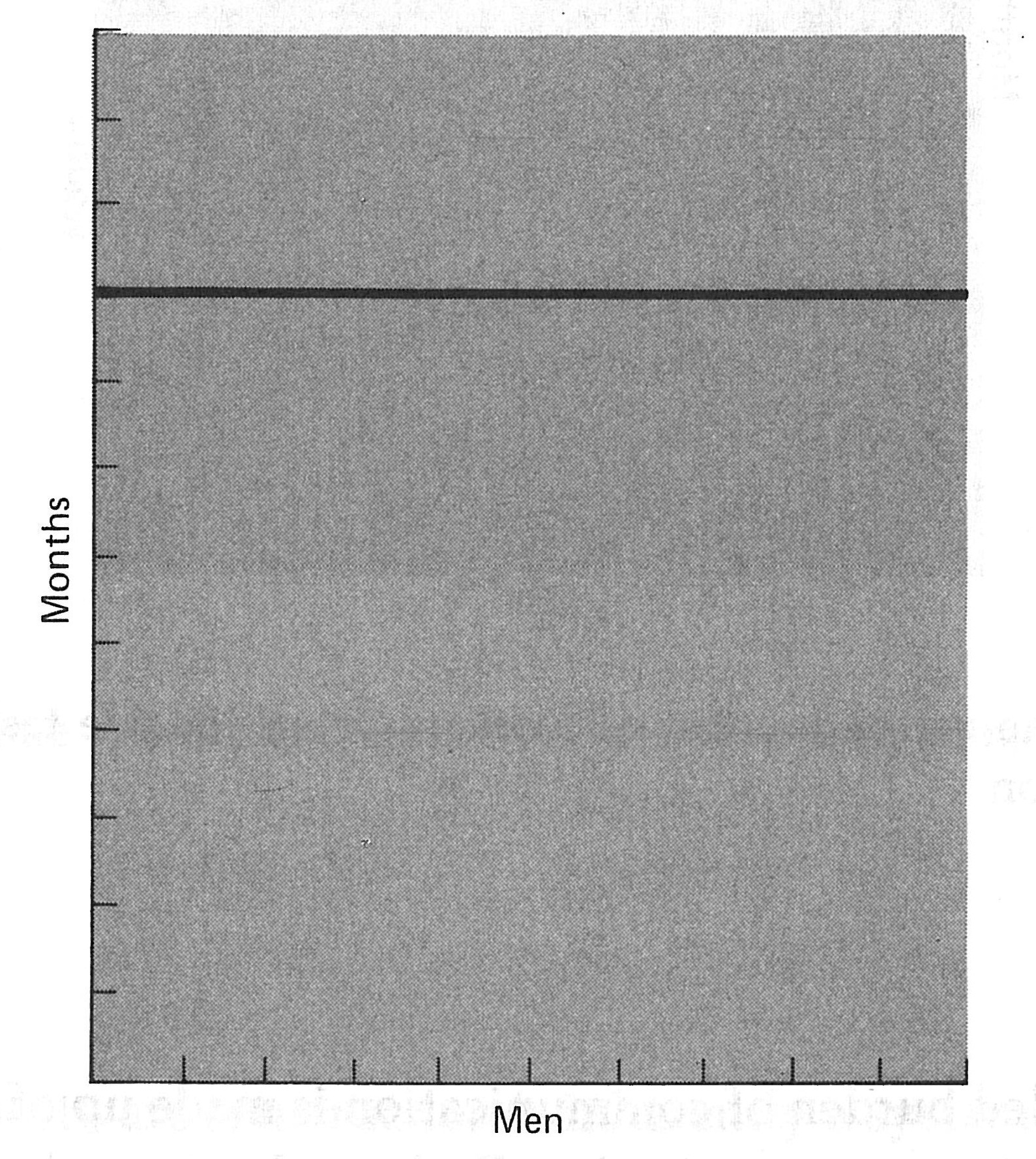

Let’s consider in a little more detail the central tenant of the Mythical Man Month, in that the addition of workers often increases the length of time the project takes. This is important concerning user experience because we can understand that adding human factors specialist may not be the best plan of action if it looks like we’re going to be late. In some cases, there can be positive benefits such as those surrounding tasks which are perfectly partition-able. In the context of user experience we can think of this as running multiple and parallel data collection activities, interviews, surveys or laboratory work in which more experimenters will be able to gather more data in parallel (see Figure: Perfectly Partitionable Task). However, the problem comes when unpartitionable tasks occur. Here we may think of tasks such is the data analysis, statistical work, in some cases report writing, etc. whereby the number of workers will have no effect because the task is unpartitionable and reasonably linear (see Figure: Unpartitionable Task). We also need to think about whether there will be a training period required for each new user experience professional. This means that the project will become even later while this training period occurs because the training period will take the resources of both the experienced UX specialists who are providing the training, as well as those new workers who are receiving training. This means that even though a full project may include perfectly partition-able tasks and perfectly unpartitionable tasks – and the full spectrum in between – it will often be the case that the things that are partition-able do not outweigh those that are unpartitionable; and further, we do not know the amount of additional training which will be required to add new workers, which may outstrip the benefits of running the partition-able tasks themselves.

Another effect, of what I think is optimism, is that described as the ‘Second System Effect’. Simply this means that the designer progresses slowly with the first system being careful because they do not know exactly what is required, they are careful to stick to the specifications that they have created. Even as embellishments occur to the designers and developers as they progress, these are stored away for the next version. However, when it comes to creating the second version the developers are buoyed by their expertise and mastery of the first system and try to cram in as many of the flourishes and embellishments from the first system as is possible. In effect this makes the second system a terrible hodgepodge of work, and in our case a terrible user interface (or interactive design). Brooks tells us that this second system is the most dangerous one to be building and gives us an example the IBM 7090 the ‘Stretch’ computer, indeed one of the developers of the ‘Stretch’ tells us that:

“I get the impression that stretch is in some way the end of one line of development. Like some early computer programs it is immensely ingenious, immensely complicated, and extremely effective, but somehow at the same time crude, wasteful, and inelegant, and one feels that there must be a better way of doing things.” [Strachey, 1962].

This fits well into our understanding of user experience, as the author suggests the system is extremely effective, however, it is also inelegant this directly contradicts our desire as previously discussed. Further, how does this equate to the Xerox Star computer? In reality, we can see that Star was developed over many iterations slowly and steadily with each iteration being used internally by the Xerox Parc infrastructure. It seems that this may be a way of mitigating the danger of adding unnecessary embellishments to a system through versions; indeed negating the second system effect may just be a simple case of eating-your-own-dog-food.

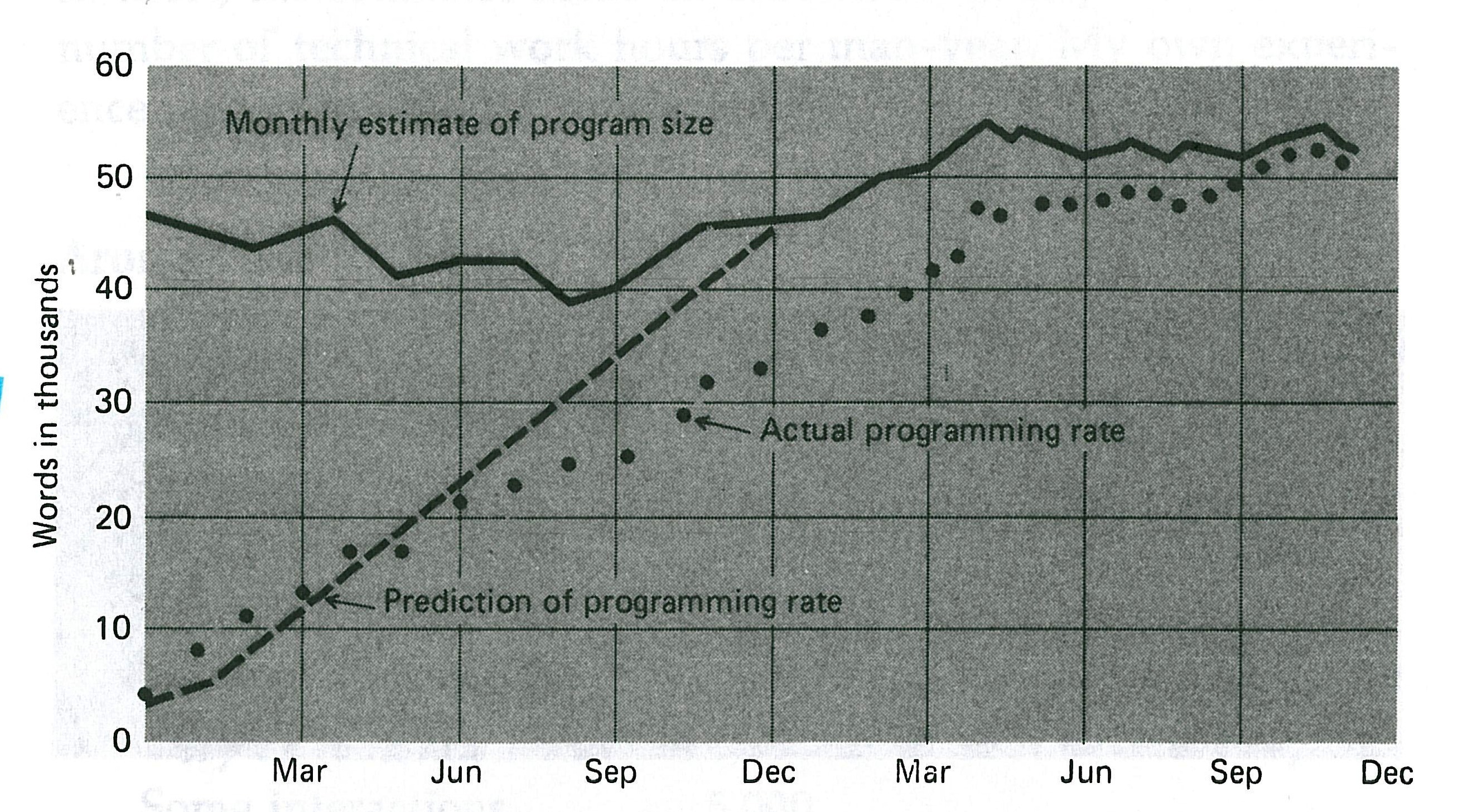

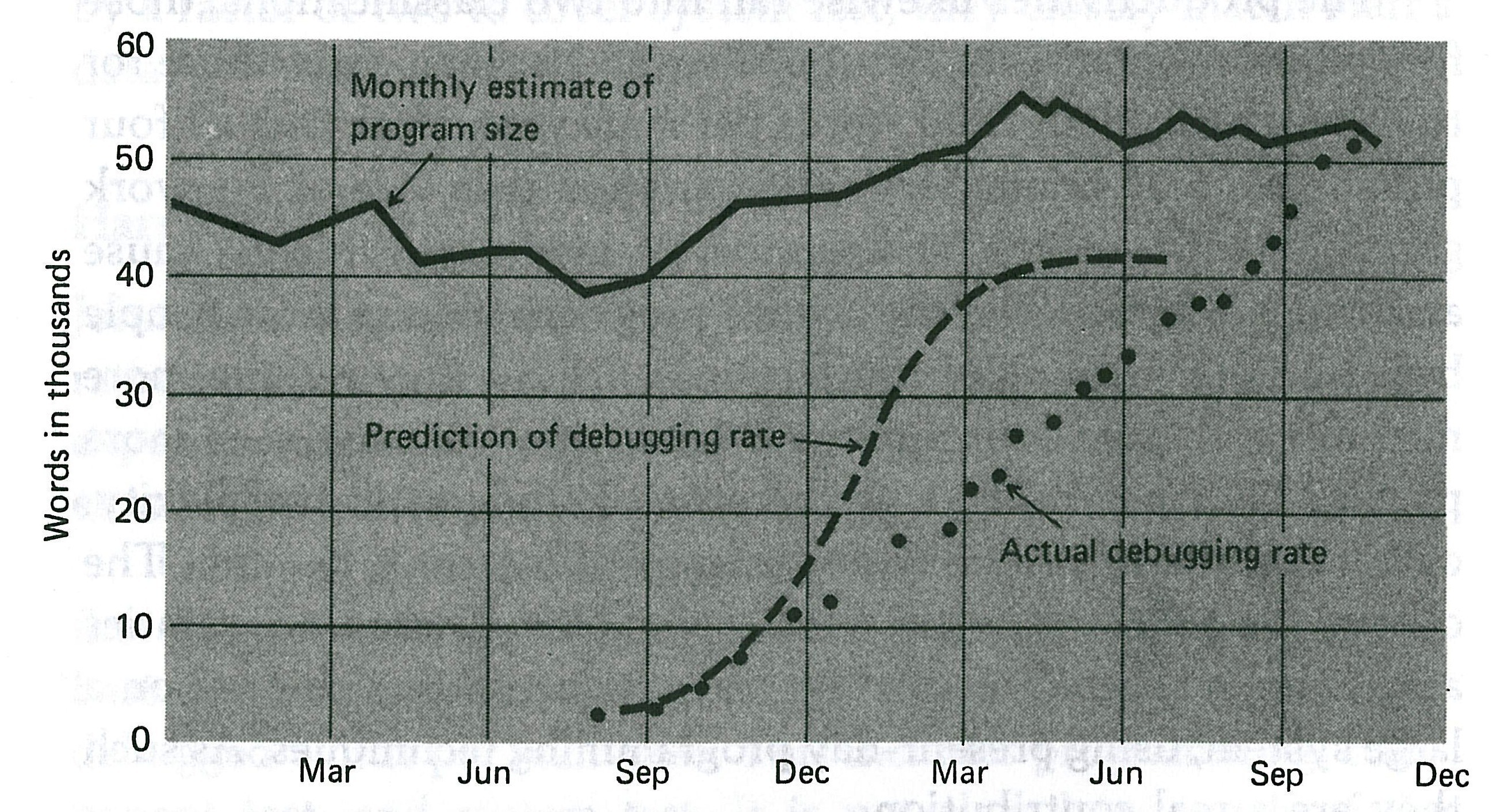

Optimism also makes predictions, both of the work required and the time it will take, inaccurate. This prediction inaccuracy can mean that what seems like short delays or inconsistencies in the work can expand into very major delays (see Figure: Programming Rates). Further, these delays can impact other aspects of the project such that the cumulative effect is far more difficult to address down the singular effect of the delay itself (see Figure: Debugging Rates). There is an old adage which asks ‘how does a project become one year late?’, The answer, of course, is ‘one day at a time’. It is up to you to understand that our predictions are often optimistic and that we need to add in extra time, if at all possible because these predictions will go awry.

One of the most important lessons to learn is that of a throwaway project. This means that you should plan to throw away the first version of anything that you create, be it a user interface design or an engineered interaction. The first version often enables an understanding of the system and aspects of the system development, but it should not be confused with a real live deployable user experience. If you do not plan to throw away one of these systems you will have to do it in the end anyhow, the only question is whether you plan in advance to throw away the first version of whether this comes upon you as a shock after you’ve delivered it to customers.

Now that you’ve recognise that the first system is the pilot system, and a pilot system will be thrown away, so you may as well plan-it in the first place, you can start to become more accustomed to the fact that changes occur, and indeed, that the only consistency is change itself. We can see that agile methods, and to some degree, the iterative design cycle makes accommodation for these constantly changing factors. But you should also realise that even though the project planner or manager may have agreed on a specification, that specification is unlikely to be the one delivered. Unfortunately, most of the interaction with customers and users will fall with you and so as the user experience specialist you need to understand that users change their minds when faced with both the system they are evaluating and in some cases the awakening concept that they can now add features that had not previously thought possible.

In this case you must think that change will occur at all levels: changes to the system, changing user requirements, changing technologies, and the changing views of the software engineers; these changes you must just take as a given. System and specification changes will occur; you must understand this, and plan for it while also enacting small steps in the UX design and the associated user interactions.

Since Brooks first suggested the concept of the throw one away project (which I subscribe to) new thought and developing, techniques have suggested that this isn’t the case. That the throw-one-away concept was predicated on the waterfall model, but now we have incremental and iterative refinement as well as agile methods. While we might be able to understand the logic of this, in real life it seems the idea of throwing a version way is still appropriate and is very useful specifically for time planning purposes. Indeed, even if we look at incremental build and agile SCRUM methods with inherent sprints, at the user experience level and (possibly because this is so close to the ebb and flow of user need, or perception) we still end up performing the same formative, summative, and development cycles again and again throwing away the older versions as the users suddenly realise that their concept of what was required is limited by their understanding of what is possible. As soon as they experience the pilot system, what is possible in their minds suddenly increases, and so this ‘increased’ system is now required2.

One thing that has come out of the work of David Parnas, and in some cases may be transferred back, is the ability to think of a software project as a family of related products; Parnas suggests this method anticipates enhanced sideways extensions and versioning.

It also seems that this is useful for the separation of concerns, and decoupling of the interface from the program logic. I would also suggest that this kind of view means that the individual applications become highly partitioned enabling user experience people to work on different interfaces for each member of this family of related projects; one failure of an individual does not directly affect the functioning of the others.

I would further suggest that moving away from the versioning tree and seeing each family member as enacting certain functionality which is specific to a particular user enables us to enact openness, open APIs, and decoupled interfaces. We, therefore, move away from one single monolithic product, which is prone to failure and a logarithmic explosion of bugs (both within the program logic and at the interface level), to a set of smaller projects more tailored to users need with the data flow occurring between individuals of the product family.

In this way, we can see that software artefacts are more tailored to the needs of the user, and resemble the user roles and stakeholders. This division enables much more personalisation of the specific individual artefact, as opposed to a massive rebuild, which may be required of a monolithic system.

17.8 Summary

Goethe says ‘What we do not understand we do not possess.’, while Crabbe says ‘O give me commentators plain, who with no deep researchers vex the brain.’

In the real world of user experience, the first is relevant to the UX specialist while the second is relevant to the user of the system. As user experience professionals if we do not understand the users or the system in total then we do not possess an ability to affect change within that system or within the users who interact with it. Without this deep understanding there is no ability for us to create accurate software artefacts or models of the users.

On the other hand, the user requires the system to speak to them in a language they understand plainly, the need for a deep understanding of how the system works and how to use it should not be required. In general, if the design of the system suggests that the system is complicated because it is for experts – and it, therefore, can’t be simplified, or made more easy-to-use – then I would be sceptical of the system designers.

The concept of the system needing expert users is often because the interface engineering or software engineering has been performed shoddily. There are some cases – and as few exceptions which may prove this rule – which exist but instead of being optimistic about a statement that I’ve heard so many times, be pessimistic. If the system cannot be used by a novice, it is most likely this is because the system is at fault and not the novice.

It is often said that there is no silver bullet, and this is exactly true when it comes to real-world user experience development. There is no system that will solve all your problems, there is no book which will present all possible options, there is no focus group or user base which you can rely on to give you accurate information, software engineers may not see the importance of the interface engineering aspects, stakeholders may have conflicting requirements, and project managers may give you no time for the work to be undertaken [Streiner and Sidani, 2010]. As the UX professional it is up to you to expect this, and therefore, take account of all these factors, your optimism, and the inane nature of the system which changes minute by minute (as does the world in which we live, the system being simply a reflection of this in microcosm); and think back to Ted Nelson.

While there might be no silver bullet (indeed the silver bullet may take away some of the challenge, and, therefore, our fun), the best advice I have is to always keep in mind the pessimistic view of an optimistic visionary “most people are fools, most authority is malignant, God does not exist, and everything is wrong.”.

17.8.1 Optional Further Reading

- [M. C. Alkin]. Evaluation essentials from A to Z. Guilford Press, New York, 2011.

- [F. P. Brooks]. The mythical man-month : essays on software engineering. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Reading, Mass., 1995.

- [J. A. Gliner], G. A. Morgan, and N. L. Leech. Research methods in applied settings : an integrated approach to design and analysis. Routledge, New York; London, 2009.

- [D. L. Streiner] and S. Sidani. When research goes off the rails : why it happens and what you can do about it. Guilford Press, New York, 2010.

- [W. P. Vogt], D. C. Gardner, and L. M. Haeffele. When to use what research design. Guilford Press, New York, 2012.

17.8.2 Self Assessment Questions

Try these without reference to the text:

- You are suffering from the ‘Too–Little–Time’ constraint and need to get a formative evaluation with 20 people (employees of the factory commissioning your new production line software) underway very quickly. At this stage, you only need qualitative results – how would you go about getting this information in the fastest time possible, and why would you be cautious?

- What are commissioning constraints?

- What is real world work limited by?

- Why is optimism often a bad mindset to have when it comes to planning UX work?

- Describe the ‘Second System Effect’?

18. Final Thoughts

‘How do I explain what I do at a party? The short version is that I say I humanize technology.’

– Fred Beecher, Director of UX, The Nerdery

As we have seen, UX refers to the overall experience that a user has when interacting with a product, system, or service. It encompasses all aspects of the user’s interaction with the product, including their emotional response, ease of use, and satisfaction with the product or service.

UX design is the process of designing products, systems, or services with the user’s experience in mind. It involves understanding the user’s needs and preferences, and designing products that are intuitive, easy to use, and provide a positive experience. It’s also associated with visual design as opposed to the broader user experience.

Good UX can lead to increased user satisfaction, improved engagement, and higher conversion rates. It is a crucial consideration for any product or service, as it directly impacts the user’s perception of the product and can determine whether or not they continue to use it.

Overall, user experience is a critical consideration for any product or service, and UX design plays a crucial role in ensuring that products are effective, engaging, and user-friendly.

18.1 Design

Designing the User Experience (UX) refers to the process of creating products, systems, or services with a focus on the user’s experience. It is a user-centric approach to design that involves understanding the user’s needs, preferences, and behaviors, and designing products that meet those needs.

The UX design process typically involves several stages, including user research, information architecture, interaction design, visual design, and usability testing. User research involves gathering information about the user’s needs and preferences through interviews, surveys, and other methods. Information architecture involves organizing and structuring content and functionality in a way that is intuitive and easy to navigate. Interaction design involves designing the way that users interact with a product, such as through buttons, menus, and other interface elements. Visual design involves designing the overall look and feel of the product, including colors, typography, and other visual elements. Usability testing involves testing the product with users to identify any issues or areas for improvement.

Effective UX design can lead to improved user satisfaction, increased engagement, and higher conversion rates. It is a critical consideration for any product or service, as it directly impacts the user’s perception of the product and can determine whether or not they continue to use it.

Overall, designing the user experience is a user-centric approach to design that involves understanding the user’s needs and preferences and designing products that meet those needs. It is a critical consideration for any product or service, and effective UX design can lead to improved user satisfaction and engagement.

18.2 Development

UX implementation refers to the process of translating the user experience design into a functional digital product. It involves using various tools, technologies, and development practices to bring the user interface (UI) to life while ensuring that it aligns with the design vision and meets the needs of the target users. Here are some key aspects of UX implementation:

- Front-end Development: Front-end development is responsible for implementing the UI design using web technologies such as HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It involves coding the visual elements, layout, and interactions to create an interface that matches the design specifications.

- Responsiveness: With the growing use of mobile devices, it is crucial to ensure that the user interface is responsive and adapts to different screen sizes and resolutions. Responsive design techniques, such as media queries and fluid layouts, are employed to create a seamless experience across devices.

- Accessibility: Accessibility is an important consideration in UX implementation. Developers need to follow web accessibility guidelines, such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), to ensure that the product is usable by people with disabilities. This includes providing alternative text for images, using proper semantic markup, and implementing keyboard navigation support.

- Interaction Design: Implementing the interactive elements of the user interface involves using JavaScript or other scripting languages. This includes creating animations, transitions, form validations, and other dynamic behaviors that enhance the user experience.

- Integration with Back-end Systems: In many cases, the user interface needs to communicate with back-end systems or APIs to retrieve and display data or perform certain actions. Developers need to integrate the UI with the appropriate back-end technologies, such as databases, APIs, or server-side scripting languages, to enable these interactions.

- Performance Optimization: UX implementation also involves optimizing the performance of the product. This includes techniques such as optimizing image sizes, minimizing file sizes, and leveraging caching mechanisms to ensure fast loading times and smooth interactions.

- Cross-Browser and Cross-Device Compatibility: The user interface needs to work consistently across different web browsers and devices. Developers perform testing and apply necessary fixes to ensure compatibility and a consistent experience for users.

- Continuous Integration and Deployment: UX implementation often follows agile development practices, where continuous integration and deployment processes are employed. This allows for regular updates, bug fixes, and improvements to be deployed efficiently, ensuring that the product remains up-to-date and responsive to user needs.

Throughout the implementation process, collaboration and communication between designers and developers are vital to maintain the integrity of the user experience and address any technical challenges that may arise. It is also common to conduct usability testing during and after implementation to identify any usability issues and make necessary refinements

18.3 Validation

Validating the user experience is a crucial process in the field of product development and design. It involves gathering feedback and data from users to assess the effectiveness, usability, and satisfaction of a product or service. By validating the user experience, businesses can ensure that their offerings meet the needs and expectations of their target audience, resulting in improved customer satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty.

The process of validating the user experience typically involves various methods and techniques, including user testing, surveys, interviews, and analytics. Key aspects centre around:

- User Testing: User testing involves observing and analyzing how real users interact with a product or prototype. It can be conducted in a controlled environment or remotely, depending on the nature of the product. By observing users’ actions, listening to their feedback, and analyzing their behavior, businesses can identify usability issues, uncover pain points, and gain valuable insights for improvement.

- Surveys and Interviews: Surveys and interviews provide an opportunity to collect feedback from a larger group of users. Structured questionnaires and interviews can help gather specific insights about user preferences, satisfaction levels, and areas for improvement. These methods can be conducted online or in person, depending on the target audience.

- Analytics and Data Analysis: Leveraging analytics tools and data analysis allows businesses to gain quantitative insights into user behavior. By tracking user interactions, such as clicks, navigation paths, and time spent on different sections, businesses can identify patterns, detect bottlenecks, and measure the success of specific features or design changes.

- Iterative Design: Validating the user experience is an iterative process. Feedback and insights gathered from users should be used to refine and improve the product or service continuously. This iterative approach allows businesses to address user concerns, enhance usability, and align the user experience with evolving user needs and expectations.

- A/B Testing: A/B testing involves comparing two or more versions of a product or feature to determine which one performs better in terms of user experience metrics. By randomly assigning different users to each version and analyzing the results, businesses can make data-driven decisions about design choices, content placement, and feature implementation.

The ultimate goal of validating the user experience is to create products and services that are intuitive, enjoyable, and valuable to users. By actively involving users in the design and development process, businesses can make informed decisions, reduce the risk of costly mistakes, and deliver experiences that delight their target audience.

18.4 As Practically Applied

In real life, the user experience (UX) process typically involves several key steps that are followed to create and validate a successful user experience. But these steps are also prone to failure and chaos as opposed to the sanitised version that is taught in the textbooks. These steps broadly proceed as follows:

- User Research: The UX process begins with user research, which involves gathering information about the target audience, their needs, behaviors, and preferences. This step may include conducting interviews, surveys, and observational studies to gain insights into user goals, pain points, and motivations.

- User Personas: Based on the user research findings, user personas are created. Personas represent fictional characters that embody the characteristics and behaviors of different user types. They help the design team understand and empathize with the users, guiding design decisions throughout the process.

- User Flows and Information Architecture: User flows and information architecture are created to define the structure and organization of the product or service. User flows outline the path users will take to accomplish their goals, while information architecture involves structuring and labeling content in a way that is intuitive and easy to navigate.

- Wireframing and Prototyping: Wireframes and prototypes are low-fidelity representations of the product’s interface and functionality. They are used to visualize and test different design concepts and interactions. Wireframes focus on layout and structure, while prototypes offer more interactivity and simulate the user experience.

- Usability Testing: Usability testing involves observing real users as they interact with prototypes or the actual product. Test participants are given specific tasks to complete, while researchers observe their actions, listen to their feedback, and note any usability issues or areas for improvement. Usability testing helps uncover design flaws, improve usability, and validate design decisions.

- Iterative Design and Feedback: Based on the insights gained from usability testing, the design team iterates on the design, making refinements and improvements. This iterative process involves incorporating user feedback, addressing usability issues, and continuously refining the user experience.

- Visual Design: Once the structure and interactions are well-defined, the visual design phase begins. Visual design focuses on the aesthetics, branding, typography, color schemes, and overall visual appeal of the product. The visual design should align with the brand identity and enhance the overall user experience.

- Development and Implementation: After the design phase, the development team takes the finalized designs and brings them to life, implementing the necessary functionalities and integrating the visual elements. Close collaboration between designers and developers is essential to ensure the design vision is accurately translated into the final product.

- User Testing and Validation: Once the product is developed, it undergoes further testing and validation. This may include user acceptance testing, beta testing with a larger user base, or even conducting additional usability tests to ensure the product meets user expectations and performs as intended.

- Post-Launch Evaluation: After the product is launched, the UX process doesn’t end. Continuous evaluation and monitoring of user feedback, analytics, and performance metrics are crucial to identify areas for improvement and plan future enhancements or updates.

It’s important to note that the UX process is not necessarily linear, and different projects may have variations in the order or intensity of these steps. However, the underlying principles of user-centered design, research, iterative development, and user validation remain consistent throughout the real-life UX process.

18.5 Final Thoughts

As we’ve seen, the UX domain is still very young and in the process of formation. But, it does bring together many already established areas within the human-computer interaction field. You may wish to think of UX as the practical application of research knowledge repurposed from other domains into the user-facing software engineering process. But by now you probably have your own view and concept of UX and UXD for that matter.

You concept of UX is valid and that is one advantage of UX as a training domain in that it is a new, practical, cross-disciplinary subject. No one has yet trained on a bespoke UX only degree programme, and so everyone has their own background and ‘slant’ to the area. There are many UX Industrial Departments/Companies, there are few UX courses. The combination of your technical Computer Science training coupled with this UX training will give you an advantage; a software focused UX professional.

Good luck in the future, and good luck in your continued UX work and study!