15. Human-in-the-Loop Systems and Digital Phenotyping

Systems simulations were a mix of hardware and digital simulations of every—and all aspects of—an Apollo mission which included man-in-the-loop simulations, making sure that a complete mission from start to finish would behave exactly as expected.

– - Margaret H. Hamilton (1965) NASA.

In the bad old days, computer systems were highly inefficient took huge amounts of resources and were not user friendly. Indeed, the head of IBM through the 50s said that he could only see the need for two computers in the world. Obviously, that was incorrect and as time has progressed, users became more important and we became more aware of the fact that humans were an integral part of the system. And so human computer interaction and therefore user experience were created. As part of this, the idea that humans in the loop would be a necessary part of a computer system was not considered until the various Apollo missions whereby human interaction with the system, indeed control of the system became important. Indeed, we may think of it as human middleware became more important, especially with computer systems flying or at least controlling complex mechanical ones.

There is an accessibility saying: ‘nothing about us without us’ and we consider that this should be extended to the human and to the user such that users are integrated into most aspects of the build lifecycle. After all, the human will be controlling the system and even in terms of intelligence systems, artificial/hybrid intelligence and machine learning, have shown to benefit from human input.

Indeed, humanistic artificial intelligence are becoming increasingly more important with most large scale computational organisations. Acknowledging this fact and having large departments which are tailored to this kind of development so for all software engineering and development the human should be considered from the outset and the humans, control actions should also be factors when designing systems which wrap around the user.

15.1 Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Systems

Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) systems are a collaborative approach that combines the capabilities of both humans and machines in a loop or iterative process. It involves the interaction and collaboration between human experts or operators and automated systems or algorithms to achieve a desired outcome. In a HITL system, humans are actively involved in various stages of the decision-making process, providing input, feedback, and guidance to the automated systems. The automated systems, on the other hand, assist humans by performing tasks that can be automated, analyzing large amounts of data, or making predictions based on complex algorithms.

The purpose of HITL systems is to leverage the strengths of both humans and machines. Humans bring their domain expertise, intuition, and contextual understanding, while machines offer computational power, speed, and the ability to process vast amounts of data. By combining these capabilities, HITL systems aim to improve accuracy, efficiency, and decision-making in various domains, such as healthcare, customer service, autonomous vehicles, and cybersecurity.

HITL systems often involve an iterative process, where humans provide initial input or guidance, machines generate outputs or suggestions, and humans review, validate, or modify those outputs. This iterative feedback loop allows for continuous improvement and adaptation, with humans refining the system’s performance and the system enhancing human capabilities. Overall, HITL systems enable the development of more robust, reliable, and trustworthy solutions by harnessing the power of human intelligence and machine capabilities in a symbiotic relationship.

HITL systems have been utilized for a long time, although the term itself may have gained prominence in recent years. The concept of involving humans in decision-making processes alongside automated systems has been present in various fields and industries for decades. One early example of HITL systems is found in aviation. Pilots have been working in collaboration with autopilot systems for many years, where they oversee and intervene when necessary, ensuring the safety and efficiency of flight operations. This demonstrates the integration of human expertise with automated systems.

NASA has embraced the concept of HITL systems across various aspects of its operations, including space exploration, mission control, and scientific research. Here are a few examples of how NASA has adopted HITL approaches. Human space exploration missions, such as those to the International Space Station (ISS) and beyond, heavily rely on HITL systems. Astronauts play a critical role in decision-making, performing experiments, and conducting repairs or maintenance tasks during their missions. While automation is present, human presence and decision-making capabilities are essential for handling unforeseen situations and ensuring mission success.

NASA’s mission control centres, such as the Johnson Space Center’s Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, employ HITL systems to monitor and manage space missions. Teams of experts, including flight directors, engineers, and scientists, collaborate with astronauts to provide real-time support, make critical decisions, and troubleshoot issues during missions. NASA utilizes robotic systems in space exploration, such as the Mars rovers (e.g., Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance). While these robots operate autonomously to some extent, human operators on Earth are actively involved in planning, commanding, and interpreting the data collected by the rovers. Humans in mission control provide guidance, analyse results, and adjust mission objectives based on discoveries made by the robotic systems.

HITL systems are prevalent in data analysis and scientific research conducted by NASA. Scientists and researchers work alongside machine learning algorithms and data processing systems to analyse large volumes of space-related data, such as satellite imagery, telescope observations, and planetary data. Human expertise is crucial for interpreting results, identifying patterns, and making scientific discoveries.

Overall, HITL approaches are integrated into various aspects of NASA’s operations, where human expertise is combined with automated systems to achieve mission objectives, ensure astronaut safety, and advance scientific knowledge in space exploration.

In the field of computer science and artificial intelligence, the idea of HITL systems has been explored since the early days of AI research. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, researchers were already investigating human-computer interaction and the combination of human intelligence with machine processing power. More recently, with advancements in machine learning, data analytics, and robotics, HITL systems have gained increased attention. They have been applied in various domains such as healthcare, where clinicians work alongside diagnostic algorithms to improve disease detection, treatment planning, and patient care. Additionally, HITL systems have become essential in the development and training of AI models. Human involvement is crucial for labelling and annotating training data, evaluating model performance, and ensuring ethical considerations are taken into account. While the exact introduction of HITL systems cannot be pinpointed to a specific date or event, their evolution and adoption have been shaped by the continuous advancements in technology and the recognition of the value of human expertise in conjunction with automated systems.

15.2 Digital Phenotyping

Digital Phenotyping (DP) can be seen as an extension (or at least has a very strong relationship to) HITL systems, in that the human in DP systems is carrying around a mobile device / wearable / or the like and their behaviour in both the real-world and in digital services. This behaviour is monitored and the collected data is used to make inferences about their behaviour.

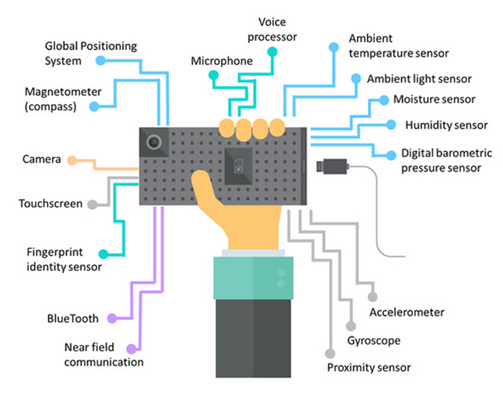

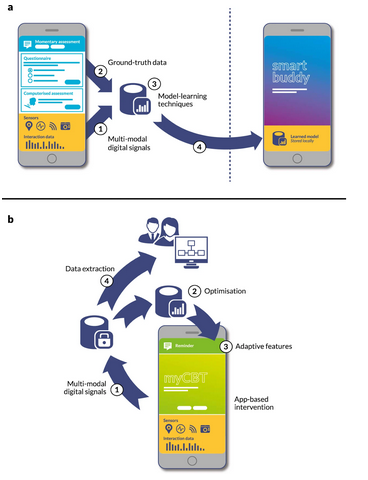

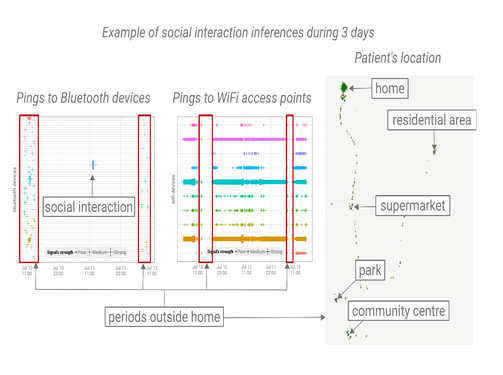

Defined by Jukka-Pekka Onnela in 2015, but undertaken for over a decade before it was named, DP utilises digital technologies such as smartphones, wearable devices, and social media platforms to collect and analyse data on human behaviour and psychological states. This approach is used to monitor, measure, and analyse various aspects of human behaviour, including sleep patterns, physical activity, social interaction, and emotional states. And uses sensors embedded in smartphones and wearables to track various physiological and environmental parameters, such as heart rate, breathing rate, and temperature, as well as factors like location, movement, and interaction with the device. The data collected is then analysed using machine learning algorithms to generate insights into an individual’s behaviour, including patterns of activity, stress levels, mental health, and well-being, and sleep quality. Roughly DP proceeds by:

- Data Collection: Digital phenotyping relies on the collection of data from individuals using their smartphones, wearables, or other digital devices. This data can include GPS location, accelerometer and gyroscope readings, screen interaction patterns, call and text logs, app usage statistics, social media posts, and more. Sensors within the devices capture data related to movement, activity, and contextual information.

- Data Processing and Feature Extraction: Once the data is collected, it undergoes processing and feature extraction. This involves converting the raw data into meaningful features or variables that represent specific behavioural or physiological aspects. For example, data from accelerometer readings can be transformed into activity levels or sleep quality indicators.

- Machine Learning and Pattern Recognition: Digital phenotyping employs machine learning and pattern recognition techniques to analyse the extracted features and identify patterns, trends, or anomalies. Algorithms are trained on labelled data to recognize specific behavioural patterns or indicators related to mental health, cognitive function, or physical well-being.

- Behaviour Modelling and Prediction: By analysing the collected data and applying machine learning models, digital phenotyping can develop behavioural models and predictive algorithms. These models can identify patterns and correlations between digital data and specific outcomes, such as predicting depressive episodes, detecting stress levels, or assessing cognitive performance.

- Continuous Monitoring and Feedback: Digital phenotyping allows for continuous monitoring and tracking of individuals’ behaviours and mental states over time. The data collected can provide real-time insights into changes in behaviour or well-being, enabling early intervention or personalized feedback.

- Integration with Clinical and Research Applications: The insights generated through digital phenotyping can be integrated into clinical settings or research studies. Mental health professionals can use the data to inform treatment decisions, monitor patient progress, or identify potential relapses. Researchers can leverage the data for population-level studies, understanding disease patterns, or evaluating the efficacy of interventions.

It’s important to note that digital phenotyping raises ethical concerns regarding privacy, data security, and informed consent. Safeguards must be in place to protect individuals’ privacy and ensure transparent and responsible use of the collected data.

DP as a term is evolved from the term ‘genotype’ which is the part of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of any individual, which determines one of its characteristics (phenotype). While phenotype is the term used in genetics for the composite observable characteristics or traits of an organism. Behavioural phenotypes include cognitive, personality, and behavioural patterns. And the interaction or interactions with the environment. Therefore digital phenotyping implies monitoring; a moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices in particular smartphones.

The data can be divided into two subgroups, called active data and passive data, where the former refers to data that requires active input from the users to be generated, whereas passive data, such as sensor data and phone usage patterns, are collected without requiring any active participation from the user. We might also equate Passive Monitoring / Sensing to Unobtrusive Monitoring and Active Monitoring / Sensing to Obtrusive Monitoring.

DP conventionally has small participant numbers however the data collected is the key and when you’re collecting ~750,000 records/person/day adaption and personalisation to a user is critical! We can think of Data as the ‘Population’ where small N becomes big N, in this case, DP supports personalised data analysis. Generalized Estimating Equations and Generalized Linear Mixed Models create a population-based model instead of a personalised one however, personal models are however needed in many complex applications. Machine and Deep Learning algorithms don’t prioritise clinical knowledge but rather structure of the data and assume the distribution of the training set is static, but human behaviour is not and often requires tuning, this requires expertise which in practice would not be available for each patient.

Digital phenotyping has many potential applications in healthcare and mental health research. For example, it could be used to monitor and manage chronic conditions such as diabetes or to identify early signs of mental health issues such as depression or anxiety. It could also be used to provide personalized interventions and support for individuals based on their unique patterns of behaviour and psychological state. However, DP has diverse application domains across mental health, and behaviour monitoring among others:

- Mental Health Monitoring: Digital phenotyping enables the continuous monitoring of individuals’ mental health by analysing digital data such as smartphone usage, social media activity, and communication patterns. It can help detect early signs of mental health disorders, track symptoms, and monitor treatment progress.

- Mood and Stress Management: Digital phenotyping can assess and track individuals’ mood states and stress levels by analysing behavioural patterns, including activity levels, sleep quality, communication patterns, and social media content. It can provide insights into triggers and patterns related to mood changes and help individuals manage stress more effectively.

- Cognitive Function Assessment: By analysing smartphone usage patterns, digital phenotyping can provide insights into individuals’ cognitive function, attention, and memory. It can help assess cognitive impairments, monitor cognitive changes over time, and provide personalized interventions or reminders.

- Physical Health Monitoring: Digital phenotyping can be used to monitor individuals’ physical health by analysing data from wearable devices, such as heart rate, sleep patterns, and activity levels. It can track physical activity, sleep quality, and identify deviations that may indicate health issues or support healthy behaviour change.

- Personalized Interventions and Treatment: Digital phenotyping insights can be used to deliver personalized interventions, recommendations, or treatment plans. By understanding individuals’ behaviours, triggers, and context, interventions can be tailored to their specific needs and preferences, enhancing treatment outcomes.

- Population Health Studies: Digital phenotyping can be applied in large-scale population health studies to understand disease patterns, identify risk factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. By analysing aggregated and anonymized digital data, researchers can gain insights into population-level health trends and inform public health strategies.

- Behaviour Change and Wellness Promotion: Digital phenotyping can support behaviour change interventions by providing real-time feedback, personalized recommendations, and tracking progress towards health and wellness goals. It can motivate individuals to adopt healthier behaviours and sustain positive changes.

As technology advances and our understanding of human behaviour and health improves, digital phenotyping is likely to find further applications in various fields related to well-being, healthcare, and personalized interventions.

15.2.1 Can you build a Digital Twin using Digital Phenotyping?

While Digital twins and digital phenotyping are related concepts in the realm of technology and data-driven analysis, but they focus on different aspects and applications.

Digital twins are virtual replicas of physical objects, systems, or processes. They are used to monitor, analyse, and simulate the behaviour of their real-world counterparts. Digital twins are often associated with industrial applications, such as manufacturing, energy, and healthcare, where they help optimize operations, predict maintenance needs, and improve efficiency. They involve real-time data integration, simulation, and visualization to provide insights and predictions about the physical entity they represent. Digital twins are more about replicating the entire behaviour of a physical entity in a digital environment. On the other-hand, Digital phenotyping focuses on the collection and analysis of data related to an individual’s behaviour, activities, and physiological responses using digital devices. It is often used in healthcare and psychology to monitor mental and physical health, track disease progression, and understand behavioural patterns. Digital phenotyping involves the use of smartphones, wearables, and other digital sensors to gather data like movement, sleep patterns, communication style, and more. The goal of digital phenotyping is to gain insights into an individual’s health and well-being by analysing patterns and changes in their digital behaviour.

This said, it is possible to incorporate digital phenotyping techniques into the development and enhancement of a digital twin, which are in many ways complimentary. By integrating data collected through digital phenotyping methods, you can create a more accurate and comprehensive representation of the physical entity within the digital twin environment.

Using digital devices such as smartphones, wearables, and other sensors to collect behavioural and physiological data from the physical entity you want to model in your digital twin. This could include data on movement, activity levels, sleep patterns, heart rate, communication patterns, and more. Then integrate the digital phenotyping data with the data streams from other sources that contribute to your digital twin’s functionality. For instance, if you’re creating a digital twin of a human body for healthcare purposes, you might combine phenotypic data with medical records, genetic information, and environmental data. Incorporate the collected data into the digital twin’s model. Depending on the complexity of your digital twin, this could involve refining the simulation algorithms to better mimic the behaviour of the physical entity based on the behavioural and physiological data you’ve collected. Analyse the digital phenotyping data to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies in the behaviour of the physical entity. This analysis can inform the simulation algorithms and contribute to a more accurate representation within the digital twin. Use the integrated data to make predictions and gain insights. For example, if your digital twin represents a person’s health, you could predict potential health issues based on changes in behavioural patterns and physiological data. Continuously update the digital twin with new data from digital phenotyping to ensure that the virtual representation stays aligned with the real-world counterpart. This real-time monitoring can help detect changes and provide early warnings for potential issues. Implement a feedback loop where insights and predictions generated by the digital twin can influence how data is collected through digital phenotyping. This can help optimize the data collection process and improve the accuracy of both the digital twin and the phenotyping analysis.

By combining digital phenotyping with the concept of a digital twin, you can create a more dynamic and accurate representation of a physical entity, enabling better insights, predictions, and decision-making in various fields such as healthcare, sports science, and more. You can skip backwards to understand how digital twins relate to requirements elicitation if you missed this.

15.3 Summary

Digital phenotyping and HITL systems are related concepts that can complement each other in various ways. Digital phenotyping relies on the collection and analysis of digital data from various sources such as smartphones, wearables, and sensors. HITL systems can play a role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the collected data. Humans can validate and verify the collected data, identify errors or inconsistencies, and provide feedback to improve the quality of the data used in digital phenotyping algorithms. HITL systems can contribute to the development and validation of digital phenotyping algorithms. Human experts, such as clinicians or researchers, can provide their expertise and domain knowledge to guide the development of algorithms that capture meaningful behavioural or health-related patterns. Humans can also participate in the evaluation and validation of the algorithms, providing insights and judgments to assess their performance and effectiveness.

Digital phenotyping algorithms generate insights and predictions based on the analysis of collected data. HITL systems can assist in the interpretation and contextualization of these results. Human experts can provide a deeper understanding of the implications of the findings, identify potential confounders or biases, and help translate the results into actionable information for healthcare providers, researchers, or individuals. HITL systems enable continuous feedback loops for digital phenotyping. Users or individuals can provide feedback on the insights or predictions generated by digital phenotyping algorithms. This feedback can help refine and improve the algorithms over time, ensuring that the system becomes more accurate, sensitive, and tailored to individual needs. Further, HITL systems play a crucial role in addressing ethical considerations related to digital phenotyping. Humans can ensure that privacy concerns, data security, informed consent, and fairness are appropriately addressed. Human judgment and decision-making can guide the responsible and ethical use of digital phenotyping technologies.

Overall, HITL systems can enhance the reliability, interpretability, and ethical considerations of digital phenotyping. By involving humans in the data collection, algorithm development, interpretation of results, and feedback loops, we can create more robust and responsible digital phenotyping systems that align with user needs, expert knowledge, and ethical standards.

15.3.1 Optional Further Reading

- [Mackay, R. S. (1968).] — Biomedical telemetry. Sensing and transmitting biological information from animals and man.

- [Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D., & Sechrest, L. (1966)] — Unobtrusive measures: Nonreactive research in the social sciences (Vol. 111). Chicago: Rand McNally.

- [Licklider, J. C. R. (1960)] Man-Computer Symbiosis, IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics, volume HFE-1, pages 4-11, March 1960.

- [Onnela, Jukka-Pekka; Rauch, Scott L. (June 2016)] — Harnessing Smartphone-Based Digital Phenotyping to Enhance Behavioral and Mental Health. Neuropsychopharmacology. 41 (7): 1691–1696. doi:10.1038/npp.2016.7. ISSN 0893-133X. PMC 4869063. PMID 26818126.

- [Harald Baumeister (Editor), Christian Montag (Editor) (2019)] — Digital Phenotyping and Mobile Sensing: New Developments in Psychoinformatics (Studies in Neuroscience, Psychology and Behavioral Economics) 1st Edition

- [David Nunes, Jorge Sa Silva, Fernando Boavida (2017)] — A Practical Introduction to Human-in-the-Loop Cyber-Physical Systems (IEEE Press) 1st Edition