6. Gathering User Requirements

I’ll sit down to work on an assignment, start sketching screens or composing an outline, then suddenly stop and say to myself, these are all ‘hows!’ What is the ‘what?’ What am I really trying to deliver?

– Marc Rettig

In his 1992 article, Marc Rettig, defines the methods we use for understanding requirements as ‘Hat Racks for Understanding’ [Rettig, 1992] -

“There is an implicit ‘what’ underlying most software projects ‘understanding.’ The users of your software are trying to learn something from the, data they are seeing. They need to understand the process of working with the software, and how it relates to the rest of their job.

They need to understand how to use the software itself. When understanding is made an explicit part of the requirements, the ‘how’ that is, the design will change. How can we help our users gain understanding? … As the collection grows, a few common themes are emerging. Some of the themes are often discussed in computing circles, such as user centred design, iterative development, user testing, and concern for human factors. These are all ‘big ideas.’ However, what I really need for my day-to-day work are a few easy-to-handle tools – ways, of thinking that will help me to do well at all those small decisions whose cumulative effect is so large…

When writers and designers want to explain something, they use visual ‘hat racks’ (maps, diagrams, charts, lists, timelines) that help us understand how our world is organised. Information hats may be hung on these racks to reveal patterns, connections, and relationships. As the scientific visualisation community has found out, one of the exciting things about computers is the way they let you dynamically change the racks on which your information hats are hanging – you can see the same information in many different ways… Although there seems to be an infinity of ways to organise information, [Wurman] notes there are really only five general ways: time; location; continuum or magnitude; and category.”

6.1 What is Requirements Analysis?

Requirements engineering is a systematic and critical process in software and system development that focuses on identifying, documenting, and managing the needs and expectations of stakeholders for a particular system or product. It plays a crucial role in ensuring that the final product meets its intended purpose and satisfies user needs. Requirements engineering (also know as ‘elicitation’) is a crucial phase in the software development or system engineering process, focused on gathering, documenting, and understanding the needs and expectations of stakeholders. The primary goal of requirements elicitation is to collect information about what the system or software should do and how it should behave. This information serves as the foundation for the project and helps ensure that the final product meets stakeholder requirements.

“Requirements analysis, also called requirements engineering, is the process of determining user expectations for a new or modified product. These features, called requirements, must be quantifiable, relevant and detailed. In software engineering, such requirements are often called functional specifications. Requirements analysis is an important aspect of project management.”

– TechTarget Network 2020

Further, requirements analysis is a phase within the broader process of requirements engineering. It involves a detailed examination and evaluation of the gathered requirements to ensure that they are complete, accurate, and well-understood. The primary goal of requirements analysis is to refine the initial set of requirements, identify potential issues or conflicts, and establish a solid foundation for the subsequent phases of the software or system development process. There are many types of requirements:Customer requirements; Structural requirements; Behavioural requirements; Functional requirements; Non-functional requirements; Performance requirements; Design requirements; Derived requirements; and Allocated requirements. Indeed, how we gather requirements can also affect the outcomes we will discuss Laboratory settings later, but briefly Laboratory settings controlled but not ecologically valid. ‘Free living’ or ‘in the field’ are ecologically valid but not controlled. Simply, ecological validity is a critical consideration in UX work, as it assesses the extent to which our findings accurately represent and can be applied to real-world situations. UX specialists strive to design studies, experiments, interfaces, interactions that balance the need for control and rigour (Laboratory) with the goal of mimicking the complexities and nuances of everyday life (free-living). This ensures that the knowledge generated from UX work has relevance and practical implications when the work is actually deployed and used.

6.1.1 Observation, Analysis, Discussion, Interpretation (OADI)

There are many different takes and methods on the steps required to gather and make sense of user requirements which will cover over the next two or three chapters. However, we can summarise these as: ‘Observation’ (Observe / Monitor / Collect) Look at what people do, and note it down; ‘Analysis’ (Analyse / Correlate) Analysis the ‘stuff’ they produce; ‘Discussion’ (Discuss / Reflect-Back) Try to find out what these observations and analysis means; and, ‘Interpretation’ adds your knowledge to the analysed data. These are not necessarily disjoint steps but can be conjoined and (or) iterative.

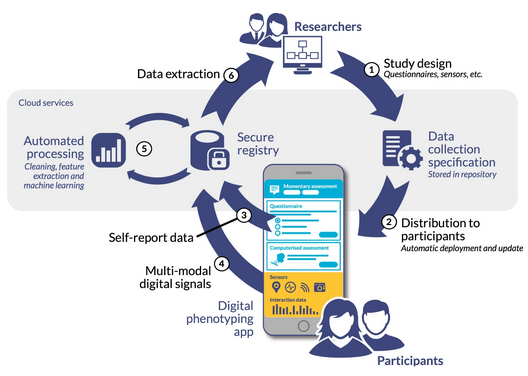

6.2 Digital Phenotyping

Digital Phenotyping is the “moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices”, in particular smartphones.

The data can be divided into two subgroups, called active data and passive data, where the former refers to data that requires active input from the users to be generated, whereas passive data, such as sensor data and phone usage patterns, are collected without requiring any active participation from the user.

The term was coined by Jukka-Pekka Onnela in 2015 but it has been undertaken for over a decade before it was named.

As can bee seen in Fig: How Digital Phenotyping Works the cycle of of data collect and then analysis is highly conjoined in digital phenotyping, and so for this reason we will cover it in more detail later. You can skip forward to a more in-depth discussion if you’d like to understand this earlier.

6.3 User Centred Design

Old-style software engineering often forgot, or ignored, the ‘what’ and, therefore, the user. As a remedy to this failing a design method – variously called user centred design, human centred design, co-operative evaluation, participatory design, or user experience design – was created which would place a user at the centre of the system. In reality, this means that there is a long user consultation period before any software is developed such that the designers can more accurately represent the requirements – the ‘what’ – of those users. It would be fair to say that there are many different sub-styles of, what I will now call, User Centred Design (UCD) and the texts and standards that are listed in this section are good first steps [9241-210:2010, 2010]. However, there are many overriding questions and principles that are appropriate to them all and in some regard can be used without strict reference to a specific UCD methodology. As a trained UX’er, you should not be following any particular method by rote, but you should rather understand the strengths and weaknesses of each and select the tools that are most appropriate to your specific requirements within you current design process6.

The term “user-centred design” was popularized and coined by Donald A. Norman, a cognitive scientist and usability engineer. In the 1980’s, Norman played a key role in advocating for a shift in design philosophy that prioritized the needs, goals, and experiences of users in the design process. Norman’s book “The Design of Everyday Things,” originally published in 1988 under the title “The Psychology of Everyday Things,” explored the principles and concepts of user-centred design. In the book, he emphasized the importance of designing products and systems that align with users’ mental models, cognitive abilities, and behavioural patterns. Norman’s work highlighted the significance of considering the users’ perspectives, abilities, and context when designing interfaces, products, and environments. He advocated for intuitive, understandable designs that minimize the user’s cognitive load and facilitate ease of use. Since the publication of “The Design of Everyday Things,” user-centered design has gained widespread recognition and acceptance as a fundamental approach in various fields, including product design, software development, and user experience design. The principles and methodologies derived from user-centred design have shaped the development of intuitive, user-friendly, and effective products and systems that meet the needs and expectations of users.

Springing from UCD came “universal usability”, a concept created by Ben Shneiderman, an American computer scientist and professor. Shneiderman is known for his significant contributions to the field of human-computer interaction (HCI) and user interface design. Shneiderman introduced the concept of universal usability in the late 1990’s as an extension of the principle of UCD. While universal design primarily focuses on physical and environmental accessibility, universal usability expands the concept to encompass digital interfaces and technologies. Universal usability emphasizes designing interactive systems and interfaces that are accessible, usable, and effective for a wide range of users, including individuals with diverse abilities, backgrounds, and levels of expertise. It aims to make technology inclusive and user-friendly for everyone, regardless of their physical, cognitive, or sensory characteristics. Shneiderman’s work on universal usability highlighted the importance of designing interfaces that are intuitive, learnable, and efficient, enabling users to accomplish their tasks effectively and efficiently. He advocated for the consideration of users’ needs, preferences, and capabilities in the design process to create interfaces that are accessible and enjoyable for all users.

Universal usability and user-centred design share common goals and principles, although they approach them from slightly different perspectives. UCD focuses on designing products, systems, or interfaces that meet the needs, goals, and preferences of the target users. It emphasizes understanding the users’ requirements, behaviours, and contexts through user research and involving users in the design process. UCD aims to create intuitive, usable, and satisfying experiences for specific user groups. On the other hand, universal usability expands the concept of user-centred design to consider a broader range of users with diverse abilities, backgrounds, and characteristics. It emphasizes designing interfaces and systems that are accessible and usable by the widest possible audience, regardless of individual differences. Universal usability seeks to remove barriers and accommodate the needs of individuals with disabilities, ensuring equal access and usability for all.

In essence, while user-centred design focuses on meeting the needs of a specific target user group, universal usability takes a more inclusive approach by considering the needs of a broader range of users. Both approaches recognize the importance of understanding users, involving them in the design process, and creating interfaces that are intuitive, effective, and satisfying to use.

Universal usability can be seen as an extension of user-centred design, incorporating accessibility and inclusivity as essential components. By considering the principles of universal usability, user-centred design can ensure that the products and systems being developed are accessible and usable by as many people as possible, regardless of their abilities or characteristics. In practice, user-centred design and universal usability can be complementary approaches, with user research and usability testing helping to uncover and address the diverse needs and abilities of users, including those with disabilities. By integrating the principles of universal usability into user-centred design processes, designers can create more inclusive and user-friendly experiences for a broader range of individuals.

UCD represents a set techniques that enable participants to take some form of ownership within the evaluation and design process. It is often thought that these participants will be in some way knowledgeable about the system and process under investigation, and will, therefore, have an insight into the systems and interfaces that are required by the whole organisation. UCD methods are closely linked to the think aloud protocol, but instead of entirely focusing on evaluation the users are encouraged to expand their views with suggestions of improvements based on their knowledge of the system or interfaces that are required. Indeed, the participants are encouraged to criticise the proposed system in an attempt to get to the real requirements. This means that – in some cases – a system design is created before the UCD have begun so that the participants have a starting point.

The UX specialist must understand that a UCD process is not a fast solution; UCD often runs as a focus group based activity and, therefore, active management of this scenario is also required. Enabling each individual to fully interact within the discussion process while the UX’er remains outside of the discussion; acting as a facilitator for the participants views and thoughts is a key factor in the UCD process. Indeed, another major difference between UCD and conventional Requirements Capture is that UCD becomes far more of a conversation between the software engineer and the user/customer.

In terms of requirements analysis7, we can think of the functional aspects to be those which are uncovered within the UCD process, while it may be convenient to think of the remaining sections of this text as more general-purpose non-functional requirements. In this case, we can see that functional requirements are those which are specific to the development in question. While non-functional requirements might be aspects such as a development should be usable; certain functionality should be reachable within a certain time frame; the system should be accessible to disabled users all users of mobile devices etc.

Of course, this is a very rigid delineation, and there is obviously some exchange between functional and non-functional requirements as defined here; but for our purposes it is simpler to suggest that functional requirements relate to a specific system while non-functional requirements relate to good user experience practise in-general. For instance, in the case of software engineering, usability is an example of a non-functional requirement. As with other non-functional requirements, usability cannot be directly measured but must be quantified using indirect measures or attributes such as, for example, the number of reported problems with the ease-of-use of a system.

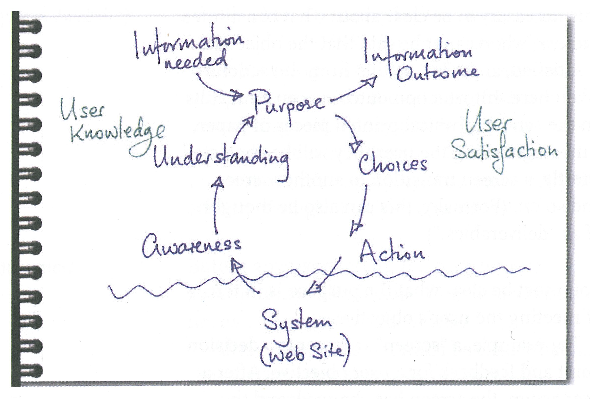

For most practical purposes, the user centred design uses an iterative looping methodology (for example [Cato, 2001] see Figure: Awareness, Understanding, Action) not dissimilar to the common software engineering iterative methodology. In this case, a requirements elicitation and analysis process, traditionally called systems requirements engineering, is undergone. This process should enable the UX’er to understand the requirements of the user and to understand how to service the tasks required by those users. It also serves to highlight aspects of the interaction or task that are important or required and gives an indication of how the user design should proceed. However at this stage, the design often does not include any decision about the user experience. Indeed, systems requirements analysis is far more about understanding the user and their place within the wider context of the system as opposed to the specifics of how the interface looks and feels.

The major difference between the traditional engineering methods and UCD is that the users participate far more in UCD and that the cycles are not so rigid. Further, requirements engineering is often more concerned that all functionality is present and that this functionality works correctly – important, to be sure. However, UCD is interested in making sure the functionality elicited in the requirements capture is the ‘right’ functionality for the users – it is ‘What People Want!’.

Once the capture has occurred it is time to communicate that information to the software engineers. This is always tricky because words and specifications tend to reduce the information to a manageable amount to communicate, but the richness of the requirements capture can easily be lost in this reduction. UCD was created exactly to address this failing – traditional methods reducing requirements to functional specifications of programmatic functionality – by adding new informal (agile) people first modelling techniques to the mix.

A modelling phase is also included when the concrete requirements for the human facing parts of the system are captured as part of a formal definition using a well-known modelling methodology such as user task analysis, Unified Modelling Language (UML) Use Case Diagrams, or general use case diagrams, etc. These modelling formalisms enable the information that has been captured in the requirements analysis phase to be transmitted to the software engineers for development and inclusion within the system8. They also enable the software engineers to tell if their system meets the UX’ers specification as defined within these models; and, therefore, enables a separation of concerns between the UX engineer and the software engineer. As is implicit in the discussion of modelling, the final stage is the development of the human aspects of the system as well as the design of the interface. In this case, a sub-iteration is often undertaken in an agile manner, often with the user being directly present. At a minimum, the user should have a high input into both the interface artefacts and should include views on how they work based on their direct knowledge of the job at hand. Once these phases have been undertaken the iterative cycle begins again until no further changes are required in any of the requirements elicitation, analysis, system design, and development.

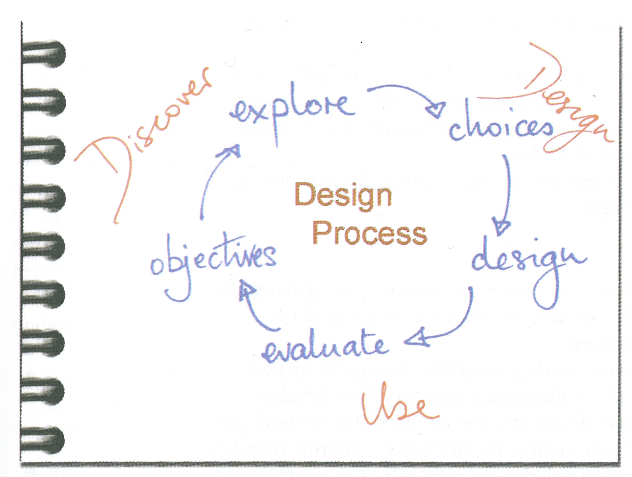

In all cases, you must think: what information do I need to build a system, how can I get this information, and how can I disseminate this information into the software engineering process, once acquired? Cato simply summarises this as Discover, Design, and Use (see Figure: Discover, Design, Use), but understanding the ‘what’ is the most important part of the equation in the requirements analysis.

One final, but important, thought before we move on; Fred Brooks in his definitive book ‘The Mythical Man Month’ states that ‘When designing a new kind of system, a team will design a throw-away system (whether it intends to or not). This system acts as a ‘pilot plant’ that reveals techniques that will subsequently cause a complete redesign of the system.’, focus on the phrase ‘whether it intends to or not’, which really means plan for a pilot - because you will, without question, be building one9.

6.4 What Information Do I Need?

Requirements elicitation is the first step within the requirements engineering process. This engineering process is often separated into three aspects that of elicitation, specification, and validation. Requirements engineering can also be known as requirements analysis that is, by coincidence, the term sometimes used to describe data analysis after the elicitation phase and before the specification phase commences. Requirements engineering encompasses all parts of the system design however here we will focus on UCD aspects and the kinds of methods that are often used early within the development cycle to elicit understanding of the users and their requirements.

The main concern for the UX’er is that the elicitation process is all-encompassing and that the specification is an accurate representation of those elicited requirements. Here we will be concerned with the elicitation; we will not be focusing on validating these requirements for one simple reason – the validation of models within the software engineering domain is neither rigorous or well understood. Most validation processes suggest that the user is involved at each stage. However, validation techniques are often more in keeping with a formal validation of the functional requirements (via Test Driven Development for instance) by the developer, as opposed to expecting high user participation. The exception to this rule is the use of prototyping techniques for understanding the correctness of the tasks and the human facing aspects of the system. If an agile method is used the validation processes is no longer required in this context. However, we can see that the UX’er must use some kind of research methodology for a final evaluation of the system.

There are many terms that are common and run through many different kinds of requirements elicitation processes, often these are used interchangeably between the different processes, and while some methods strictly refer to specific terminology, developers seem to be less pedantic than methodology designers. The basic format when trying to elicit a user’s requirements – the what – is often regarding the role of the user, the action a user (a role) wishes to enact, and the information or object on which that action should be elected. There are different names for this kind of model: roles, actions, and objects; and users, actions, and information are but two.

Further, there is a common vocabulary to describe a user role. These user roles are often described using terms such as actor, stakeholder, role, or proxy, and all users have the desired goal, thus:

- ‘Actor’ refers to a specific instance of the users such as a customer, manager, or sales clerk and indeed in some cases the term actor is prefixed by their priority within the specific methods such as a ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’ actor. However, in all cases the actor is someone who actually initiates an action within the system;

- ‘Stakeholder’ is similar to an actor in that they are a class of user but, in this case, they are less involved within the actual initiation of the action, instead having an interest in the outcome;

- ‘Role’ is also closely related to an actor or a stakeholder in that it describes the persona the user will be taking, such as a purchaser or a seller. Moreover, in some cases may also be used to refer to the similar class of users as in the actor, such as a customer, manager, or sales clerk for instance; finally, the term

- ‘Proxy’ is used to describe a person who is not a specific user but is playing that role. In this case a proxy sales clerk may actually be a manager who is relating the requirements of the sales clerk to the developer based on their knowledge of the job but actually who do not perform the job directly; mostly this is because the actual user is not available.

Finally, the term ‘Goal’ is used to describe the outcome that is required by the actors or stakeholders and these may vary based on the role that each of the users is playing.

The next term to consider is the ‘action’, and, in this case, it is often listed as a plain English phrase such as ‘track my order’, or ‘buy the book’, or ‘compare functionality’. We can see that these terms make a very good descriptors for function or method statements within the main code, and so are often used as such by the software engineers. Finally, an ‘object’ is required for these actions to work upon. In this case, we can derive objects by looking at the nouns within these action phrases such as ‘order’ or ‘book’. In other cases, we must create the object-name if this is not explicitly described – such as ‘functionality’ – in which we might want to create a ‘specification’ object of each item.

So then we can see that in most cases these kinds of terms – and the way you should be thinking – applies to most UCD methodologies; it turns out that thinking about the ‘what’ is not as complicated as we may have imagined.

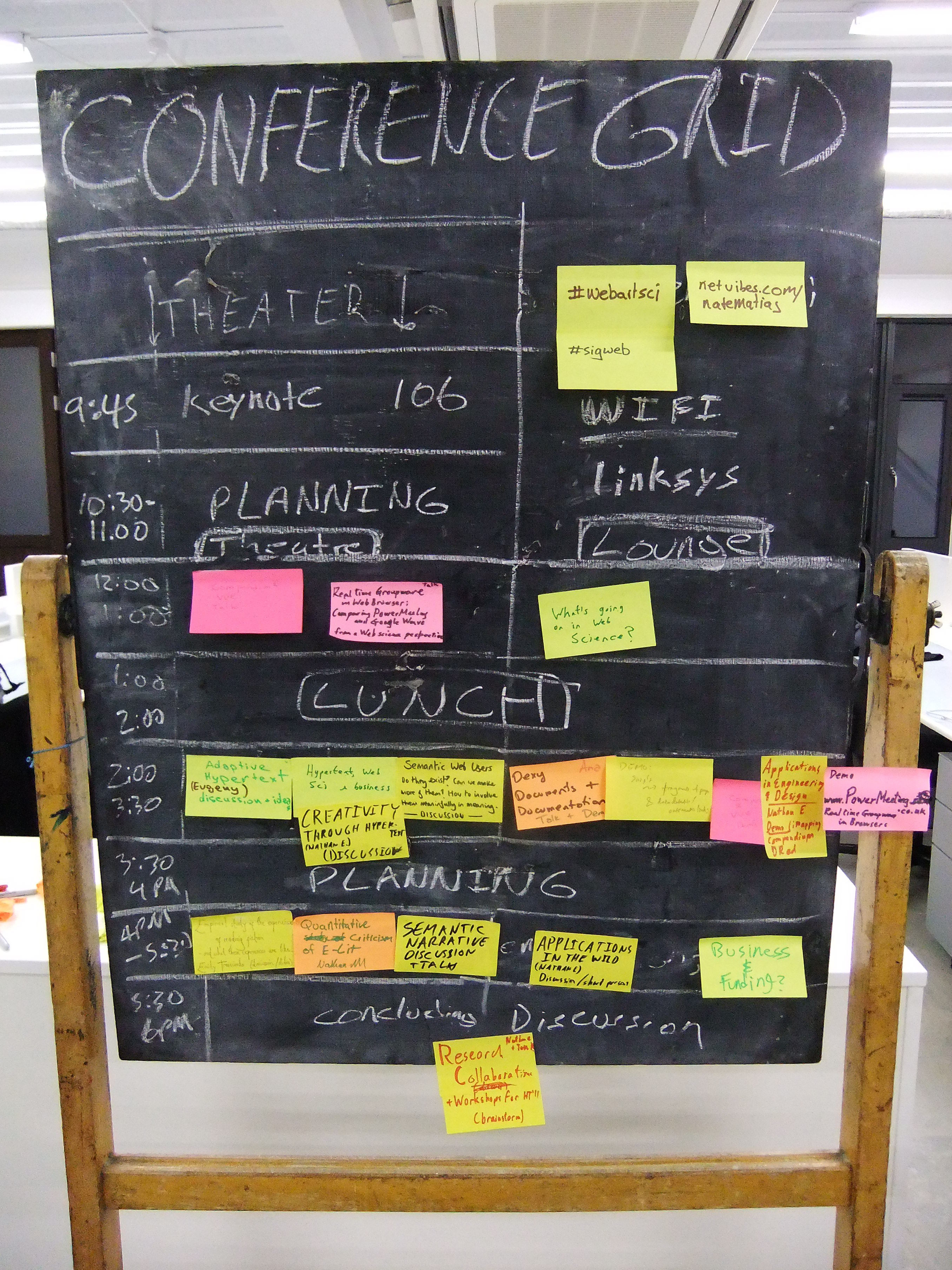

6.4.1 The Humble Post-It!

There are many tools to use in the user-centred requirements elicitation process, but strangely one of the most effective is the humble post-it note. Through the 70s 80s and 90s, a vast amount of effort was directed into creating computerised design tools specifically for the purpose of conveying design information to the software engineer10. The thought was that by computerising the elicitation process we could capture and easily link user requirements that would then serve as the basis of the generated software model; thereby removing the possibility of introducing errors into the mapping from design to software. However, along with this logic for computerisation was introduced a certain inflexibility into the design. Once the text was entered into the system it was very rarely changed or updated, once typed, once printed, it was seen in some way as immutable.

Then in the late 1990s and early 2000 came the use of the post-it note. The post-it note offers the flexibility that anything can be written on it, anything can be designed upon it, and it can be placed and moved in many and varied different ways, and on many different surfaces; mostly walls and whiteboards. People could scrawl something and decide later to throw it away, people could write something place it in a certain position – clustered with a post-it notes – and at a later point easily change it to a different position.

The post-it note facilitates the evolutionary design process, and in my opinion, this is without a doubt one of the most important tools to arise in the requirements capture space for a long time.

Now the post-it note is used in many different scenarios: from creating a conference grid (see Figure: Conference Grid – in this case at the WebArtScience Unconference in London 2010), to building an agile development, through to mapping the emergent requirements of a user centred design (see Figure: Post-Its in Development).

The first tool you should reach for when starting any design elicitation and mapping process is the post-it note. It will enable a design11 to emerge from the users, using a tool that they consider unthreatening, obvious, and familiar. Further, post-it notes have the advantage over other mediums, such as the whiteboard, in that with post-it notes everyone can have his or her say. Everybody has a pen/marker, and everybody has a means of conveying his or her ideas. Remember, once the text is removed from the whiteboard information is lost, a post-it note can be moved to one side such that the idea is not lost. Moreover, the evolution of the design is still recreate-able – but maybe does not stay within the focus of the discussion.

Once you have completed this elicitation phase you’ll be left with clusters of post-its on a wall or whiteboard, in some cases these will be reasonably neat and orderly, in other cases they will be in informal ‘scrappy’ clouds. You should now photograph those clusters, possibly after you have numbered each post-it note such that you can recreate the clouds at any point in the future, if necessary. Both information on a post-it note and their arrangement on the wall have to mean, and you should consider this meaning when trying to formalise these designs for the software process.

6.5 How Do I Get ‘The Information That I Need’?

Most methods for collecting data come from a combination of anthropology and sociology12 mushed-together with some minor alterations to make them more amenable to the UX’er. This ‘modified-mush’ owes much to social anthropologists following the theoretical tradition of ‘interactionism’; interactionists place emphasis on understanding the actions of participants by their active experience of the world and the ways in which their actions arise and are reflected back on the experience. This is useful for the UX’er as the interactionists component of the method makes it quite suitable for requirements capture focused on tasks and systems.

To support these methods and strategies, many suggest the simultaneous collection and analysis of data. This implies the keeping of substantive notes consisting of a continuous record of the situations events and conversations in which the UX’er participates; along with methodological notes consisting of personal reflections on the activities of the UX’er as opposed to the users –‘Memoing’. These notes should be preliminary analysed within the field and be indexed and categorised using the standard method of ‘Coding’ different sections of the notes to preliminary categories which can be further refined once the requirements capture has concluded.

The most used methods for requirements capture are participant observation, interviewing, archival and unobtrusive methods. I suggest that these methods are mainly used for building a body of understanding that is both deep and narrow in extent and scope. This knowledge can then be used to help guide our development. You can expect a better outcome if a variety of methods is used in combination – however, in reality you will mostly be limited by time.

6.5.1 Got Six Months?

Imagine you are UX’er employed within a company that has just acquired a different organisation. Your company needs to know the processes that are followed within this newly purchased company. You need to understand what kind of jobs their employees do, the systems that they follow, and the level of computerisation, you then need to build an assessment of how their systems and business processes will fit into yours. Even if you only have a small amount of time (six months, say) you will be able to gain a high level of detailed understanding, and scope out the problems of integration, by utilising the ethnographic methodology of observation or participant observation.

Participant observation, is the process by which data is gathered by participating in the daily life of the group or organisation under study. The UX’er watches the people in the study to see what situations they normally meet and how they behave in them and then enters into discussion with some or all of the participants in the situations to discover their interpretations of the events that have been observed. These discussions are often called ‘conversations with a purpose’ and are very (very) informal interviews – in that you want clarification of certain points without being too prescriptive so as not to bias the users answer. Special classes of participants, called ‘informants’, may also be called upon, informants are usually ‘people-in-the-know’. The person or persons selected to be informants, therefore, have a broad knowledge of the organisation, its services, and its people and can provide clarifications and corroboration for data collected while in-situ. The ‘key informant’ has an additional significance to the UX’er, which may be because they have extensive knowledge of the user roles, the actions they perform, or the objects on which they perform those actions. They may also host the UX’er in their team, or sometimes because they were the initial contact for the UX’er and served to introduce them into the department or team. Key informants are an excellent way to recover information about past events or organisational culture and memory that are no longer observable. Once in the team the observations of the UX’er should be methodical and verbose in their note taking and thoughts. Eventually, you will begin to take fewer notes, witness less novel situations, and start to have fewer novel insights; this is an indicator that your observations are coming to an end.

You should remember that you sampling must be representative and that you should remain in the team/organisation until all requirements are captured. Behaviour should be sampled in natural settings and whenever possible be comparative; with the samples and sampling procedure made public. Sampling strategies include probability sampling, in which every unit of the universe under study has the same calculable and nonzero probability of being selected; and non-probability sampling, where there are no means of estimating the probability of units being included in the sample. Non-probabilistic techniques include judgement and opportunistic sampling, in which samples selected are based on opportunity or the need for a certain kind of sample. Snowball sampling, in which an initial set of key informants provide access to their friends and colleagues, thereby forming a larger set. Finally, theoretical sampling, often used in natural settings, is the process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes, and analyses, the data and decides what to investigate next to develop the theory as it emerges.

While there may be some roles the UX’er may take, these are constantly negotiated and re-negotiated with different informants throughout the requirements capture. Therefore, it can be seen that the interpretive nature of the work means that your role is also important including the influence of your specialism, experience, age and gender, and ethnicity, concerning that of the user group. Remember, as a UX’er you need to observe events by causing as little affect as possible and develop trust and establish relationships often by learning a shared vocabulary that is appropriate to various organisational settings.

You may wish to be more prescriptive than observation if time is limited and focus on ‘Task Analysis’. Task analysis is used to refer to a set of methods and techniques that analyse and describe the way users do their job regarding the activities they perform, including how such activities are structured, and the knowledge that is required for the performance of those activities. The most common and simplistic form is hierarchical task analysis in which a hierarchy of subtasks are built to describe the order and applicable conditions for each primary task.

The reality is that these look like very simple procedures for accomplishing tasks. However, there is a large amount of implicit information captured within these constructs. For example, if a user wishes to borrow a book from the library then part of the task analysis may be that a new checkout card is required, and subtasks may be that the current date needs to be entered on that card as does the borrower’s name and catalogue number of the book. In this case, we can see that any automated system must make provision for a pseudo-checkout code to be created and that there must be the fields available for capturing the date, name, and catalogue number within that pseudo-checkout card.

In reality, you can use task analysis to analyse the notes you have collected in your more free-form observations, or if time is limited, focus only on tasks. In this case, you sacrifice completeness, richness, and nuance of time savings (there may not be a cost saving if the requirements capture is incomplete).

In summary then, we can see that the time-scale for observation work is quite long; between six and twelve months in some cases. This means that when conducting requirements capture in an industrial setting cost constraints often conspire to remove observation from the battery of available techniques. Even so, the use of the key informant as the principal means of soliciting information concerning organisational jargon, culture, and memory can be useful to enhanced other types of research method.

6.5.2 Got Six Weeks?

Imagine working for a company that is trying to specify the functionality for a new computer system. This computer system will move the individual paper-based systems of the sales department and those of the dispatch department into one streamlined computerised sales and dispatch system. In this case you know some of the pieces, you know some of the systems that already exist, you know your own company’s business processes and have an understanding of the organisational knowledge. However, you do not know the detailed processes of the sales and dispatch departments separately; and there is no documentation to describe them. Also, you do not know the interface that currently exists between these two departments and so you cannot understand the flow of information and process that will be required in a unified system. In this case, it is useful to employ focus group techniques followed up by structure or semi-structured interviews.

Group interviews – Focus Groups – are used to enable informants to participate and discuss situations with each other while the UX’er steers the conversation and notes the resultant discussions. In the role of moderator (and scribe) the UX’er needs to think of the most practical considerations of working with an organisation. For instance, logistics, piggybacking on existing meetings, heightened influence of the key informers, group dynamics, adhering to the research agenda and spontaneity, and the difficulty in ensuring confidentiality.

A variation on the focus group is the respondent, or member, validation. This is the process whereby a UX’er provides the people on whom the requirements capture is conducted, with an account of the findings; with the aim of seeking corroboration, or otherwise, through the various interview methods. Leading on from these validatory discussions, is the concept of action research which is related to participatory design, participatory research and the practitioner ethnographer. Here, a UX’er along with the users collaborate on the diagnosis of a problem and the development of a solution based on that diagnosis. In reality, this means that the trained UX’er guides the un-trained users in an attempt to evolve a knowledge of the problem and the possible solutions to that problem.

Interviewing is a useful method in requirements capture, However, you can deliver these in both a structured or a semi-structured interview style. These often take place as friendly exchanges between the user and the UX’er to find out more about the organisation or the users job. Interviewing techniques are best applied when the issues under investigation are resistant to observation. When there is a need for the reconstruction of events. When ethical considerations bar observation. When the presence of a UX’er would result in reactive effects. Because it is less intrusive into the user’s day, because there is also a greater breadth of coverage; and finally, because there can be a specific focus applied.

Both single participant interviews or focus group discussions are rarely conducted in isolation and are often part of a broader requirements capture drawing on the knowledge of the UX’er in their application. It is sometimes normal for an aide memoir to be used concerning the interview often. However, all topics are not covered. Three main types of questions are used; ‘descriptive questions’ that enable users to provide statements about their activities; ‘structural questions’ which tend to find out how users organised their knowledge; and finally, ‘contrast questions’ which allow users to discuss the meanings of situations and provide an opportunity for comparison to take place between situations and events in the users world.

In this way, both structured and unstructured interviews are useful to the UX’er because they enable a direct confirmation of partial information and ideas that are being formed as the requirements capture continues. These interviews are often conducted as part of focus group discussions – or afterwards for clarification purposes – because in some cases the communal discussion enables joint confirmation of difficult or implicit aspects of the area under investigation.

Social Processes The social processes that go along with the requirements elicitation phase are often overlooked. For the UX analysts, this is one of the most important aspects of the work, and it should be understood that implicit information mentioned as part of social interactions in an informal work environment may have a high degree of impact upon the requirements engineering phase. Aspects of the work that is not self-evident, errors that often occur, and annoyances and gripes with a system that is not working correctly often come out in an informal social setting; as opposed to the most formal setting of a systems design interview.

In this case, it should be abundantly clear that spending social time with prospective users of the system is useful for catching these small implicit but important pieces of information which are often ignored in the formal process. A full understanding of the system requirements is often not possible in a formal setting because there may be political expediency in not bringing negative aspects of the system to the attention of the requirements engineer; especially if these aspects of the system were designed by management. Further, users may also consider aspects of their job, or the system, too obvious to be explicitly expressed.

In summary, then, we can see that the time-scale for interviewing, focus group discussions, and participatory work can be short to medium term; between one and three months in some cases. This short timescale in data gathering is the main factor attributed to the popularity of these techniques. The data returned is not as rich as that gathered by observation because the UX’er already has some idea of the domain, and enacts some control over it; for instance, in the choice of questions asked. However, interview methods and variants often provide an acceptable balance between cost, time, and quality of the data.

6.5.3 Lack of Users?

How do you understand the organisational processes that need to be computerised if the people with the most experience have retired or been made redundant? Further, if a computer system does not already exist, how do you also know what the look and feel of the system should be like? If there is no electronic reference point, or reference point for the processes that need to be undertaken, how can you derive this information? Simply, by an investigation of the archival materials of the organisation, paying specific attention to the processes that you are trying to replicate, you should be able to rapidly prototype an initial system that can then be refined by real world user interaction.

An archive is a collection of historical records that have accumulated over the course of an individual or organisation’s lifetime. The archives of an individual may include letters, papers, photographs, computer files, scrapbooks, financial records or diaries created or collected by the individual - regardless of media or format. This means that other computational resources can also be used, such as online photos, avatars, WebCams, and video recording, as well as discussion forums, email archives, mailing-lists or electronic distribution lists. Administrative files, business records, memos, official correspondence and meeting minutes can also be used. There are two different kinds of archival records, being, the running record and including material such as wills, births, marriages, deaths, and congressional records, etc. In contrast to this there are episodic or private records such as sales records, diaries, journals, private letters, and the like. Archival records are normally unpublished and almost always unique, unlike books or magazines, in which many identical copies exist. Archives are sometimes described as information generated as the ‘by-product’ of normal human activities.

The importance of historical records is precisely because of their by-product nature. These records can be classified as either primary sources or secondary sources based on whether they are summarised or edited; touched by someone after their creation. Primary sources are direct records such as minutes, contracts, letters, memoranda, notes, memoirs, diaries, autobiographies, and reports; and secondary sources include transcripts, summaries, and edited materials. The second distinction is between public documents and private documents and solicited and unsolicited responses. Life histories, autobiographies from an insiders point of view are also very useful as well as diaries and diary interviews. Letters are considered to be an important source as they are primary, often private, and mostly unsolicited, therefore they are written for an audience and captured, within the writing, is an indicator of the different kinds of social relationships within the letter style. However, a degree of circumspection is required when evaluating personal documents as to the authenticity, the authors possible distortion and deception.

Once selected, an archival material can be subjected to analysis as part of the process of understanding the work and placing it in context; you could think of this as being similar to data-mining. Content analysis is an approach to the analysis of archival material that seeks to quantify content regarding predetermined categories; a process called ‘coding’. Aspects that may be sampled are significant actors, words, subjects and themes, and dispositions. Also, secondary sources may be subject to a secondary analysis, in that data, which has been pre-collected, undergoes a second analysis possibly having completely different research questions applied than the original creator of the secondary source had in mind.

Organisations run on forms, order forms, summary sheets, time-sheets, work rosters, invoices, and purchase orders, in fact, any written systemised approach to fit data into a well understood homogenised format. In this way, forms provide an implicit understanding of the kinds of work that prospective users will carry out, the terms that will be familiar to them, and information requirements that are not used as well as those that are overused. Therefore, it is easy to see that forms are a structured collection of system requirements. The positive aspect of understanding forms is that their interpretation is often very straightforward. Whereby users neglected to make certain obvious aspects of the work they do forms do not, further, the acquisition of forms and their processing is easy because forms are commonly available within the organisation. Indeed, in many cases forms can be used to reverse engineer a database schema including attributes entities and relationships that go to make up that schema. This means that the results of this kind of analysis are far more amenable to formal modelling than other kinds found in the elicitation processes.

As with all good computer science, data reuse is a primary concern, and this is also the case with requirements capture. The UX analyst should look out for requirements that have already been captured for some other application. These may be reusable in specifying a similar application or can be reanalysed to add extra depth to the requirements elicitation process already underway. Indeed, even though previous requirements documents may be out-dated, some aspects may serve as a useful starting point to begin interview discussions or focus group activities. Here questions about the old system, in comparison to the new system, can be posed, and the responses of the users gauged to inform the creation of the new system. In addition to standard requirements reuse, aspects of the specification can be reverse engineered such that some of the analytical information can be identified and indeed parts of the current software or systems processes can also be reverse engineered to identify their constituent parts enabling the creation of models that form a higher level of abstraction.

In summary, then, grabbing and analysing archival; material – old forms, reports, past memos, and the like – all help the UX’er without users to create a picture the needs of the organisation and users they are working with. It is rare that archival material will be your only source for requirements capture, but it may be a good initial starting point if your users do not have the time, initially, to spend bringing you up to speed.

6.5.4 Relationship to the Digital Twin

A digital twin is a virtual representation of a real-world physical object, system, or process. It’s a digital counterpart that mirrors the physical entity in a digital environment, often in real-time or near-real-time. This concept emerged from the convergence of technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), data analytics, and simulation.

Digital twins are used across various industries, including manufacturing, healthcare, energy, aerospace, and more, to provide insights, analysis, and predictions about the real-world counterpart. They can range from simple models representing individual objects to complex models representing entire systems or environments.

Digital twins provide a visual representation of the physical entity, making it easier to monitor and understand its status and behaviour. They incorporate data from sensors, IoT devices, and other sources to reflect the real-time conditions and performance of the physical counterpart. Digital twins enable simulations and “what-if” scenarios, allowing businesses to test changes, optimizations, and potential outcomes before implementing them in the physical world. By analysing historical and real-time data, digital twins can provide predictive insights into potential issues, failures, or performance improvements. Digital twins allow remote monitoring and management of physical entities, facilitating maintenance, troubleshooting, and adjustments from a distance. As more data is collected and analysed, digital twins can be refined and improved, leading to a better understanding of the physical entity’s behaviour.

The concept of digital twins continues to evolve, driven by advancements in technology and the increasing need for efficient data-driven decision-making in various industries. So in reality when you are gathering requirements you are often intent on being able to build a digital twin of the real world process or system. You may of course wish to improve things but in the first place you need to understand and at least digitally model the current system be that digital or analogue. You can skip forward to understand how digital twins and digital phenotyping relate if you’d like to understand this earlier.

6.6 Summary

Once the elicitation and analysis phase has been complete it maybe time to move this knowledge into a more formalised description of the user, which can be understood by the software engineers and, therefore, used to develop the user-facing aspects of the system. In this case, we can see that requirements elicitation is not dissimilar to knowledge acquisition. The major problem within the knowledge acquisition and requirements elicitation domain are that analysts have difficulty acquiring knowledge from the user. This can often lead both domains into what has become known as analysis paralysis. This phenomenon typically manifests itself through long phases of project planning, requirements gathering, program design and data modelling, with little or no extra value created by those steps. When extended over a long timeframe, such processes tend to emphasise the organisational and bureaucratic aspects of the software development, while detracting from its functional, value-creating and human facing portion.

6.6.1 Optional Further Reading

- [A. D. Abbott] Methods of discovery: Heuristics for the social sciences (contemporary societies). WW Norton & Company, 2004.

- [S. W. Ambler.] The elements of UML 2.0 style. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005.

- [R. G. Burgess] In the field: An introduction to field research. Routledge, 2002.

- [J. Cato]. User Centered Web Design. Addison Wesley, 2001.

- [P. Loucopoulos] and V. Karakostas. System requirements engineering. International Software Engineering Series. McGraw-Hill, 1995.