Connecting Analog Sensors to the Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi is a marvel of connectivity. It’s 40 pin header and associated peripheral ports provide a spectacular range of options to interface with the world outside the Raspberry Pi. However, one feature that the Pi doesn’t have built in is the facility to accept an analog input.

Analog and Digital

Signals (or even information in general) can be broken down into two different types; Analog and digital.

Analog

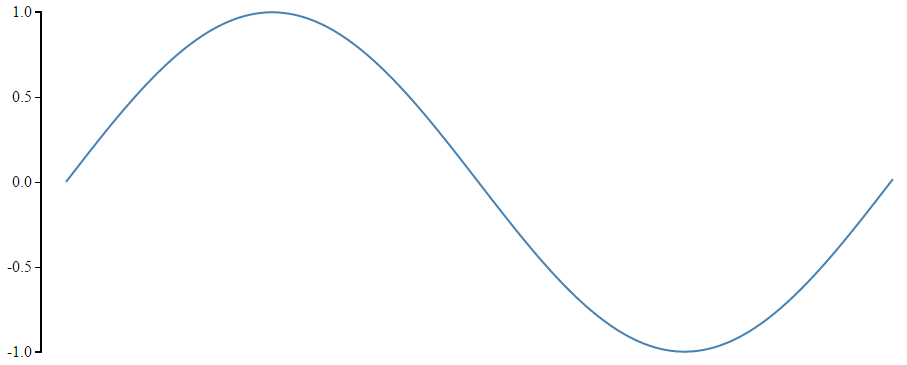

An analog signal is one that has an infinitely variable range of values that can change over time.

If we consider the question of how much light is shining outside we could imagine that the level of brightnesses varies between the blackness of a moonless night and a overcast sky to a cloudless day with the sun high in the sky.

These are rough approximations of dark and light, but between the two extremes is a range of brightness levels which are always changing. If we wanted to measure how bright it was at any particular time we could set ourselves a numeric range of 0 representing the middle of the night and 100 representing the middle of the day and the number that represented the brightness at any particular time would be somewhere between those two numbers. Typically in electronics an analog signal is a voltage that will be anywhere on that variable range between two limits.

Digital

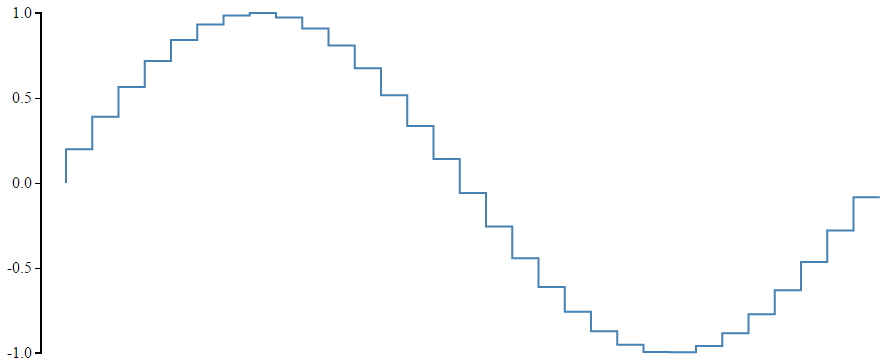

A digital signal represents information as discrete values.

For example at it’s most fundamental the light level outside could be described as dark or light. Represented numerically this could be dark = 0 and bright = 1. While this is perfectly valid, we would often prefer to have a little more granularity in our measurement and so we can increase the number of discrete steps that represent light levels to match our expectations of the type of information we’re interested in. if we add another couple of levels in we could have light that was dark = 0, dim = 0.33, glowing = 0.66 and bright = 1. We can continue to improve the resolution of our numerical perception of the level of light in a process that is called Analog to Digital Conversion or ADC.

Analog to Digital Conversion (ADC)

Luckily there are a wide range of options available to convert analog signals into digital ones. Therefore, people wanting to input an analog signal into a Raspberry Pi can simply include a separate ADC into their project and it will work wonderfully. That’s what we’re going to do here using the ADS1015 from Adafruit. The ADS1015 has a 12bit resolution giving it the ability to convert an analog signal into one of 4096 discrete levels.

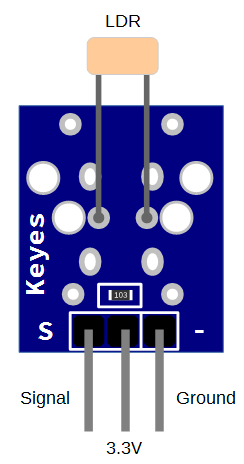

The Sensor

While this project is more about the conversion of analog signals into digital ones, this project will use a Keyes KY-018 sensor based on a Light Dependent Resistor (LDR) to produce a variable resistance in the presence of different light levels. An applied voltage (from the Pi) returns a variable voltage from the LDR. It is this variable voltage that is then digitised with the ADC.

In essence there are a range of different sensors that could be used. I have successfully also connected the Keyes analog hall effect sensor (KY-035, which senses magnetic fields) and there will be others in that range that will work.

Data Visualization

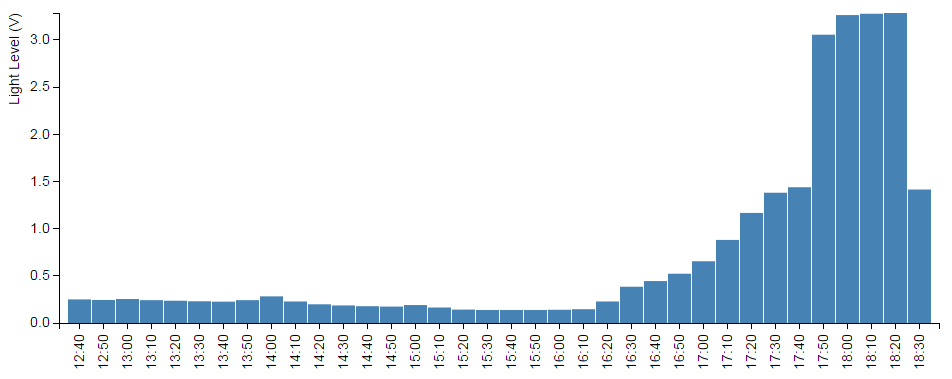

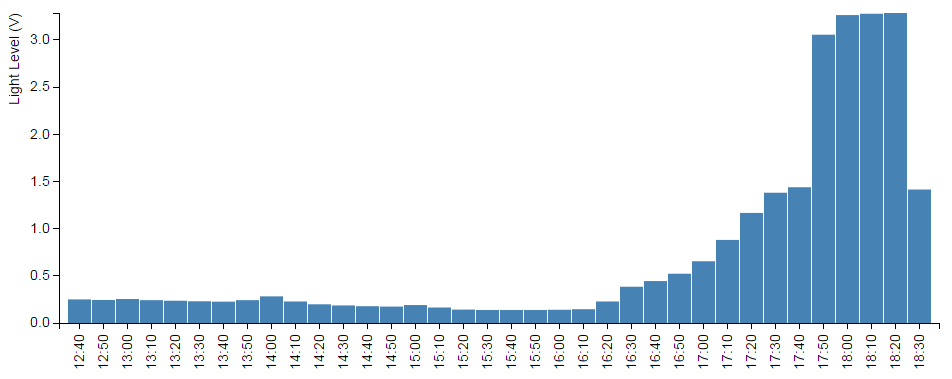

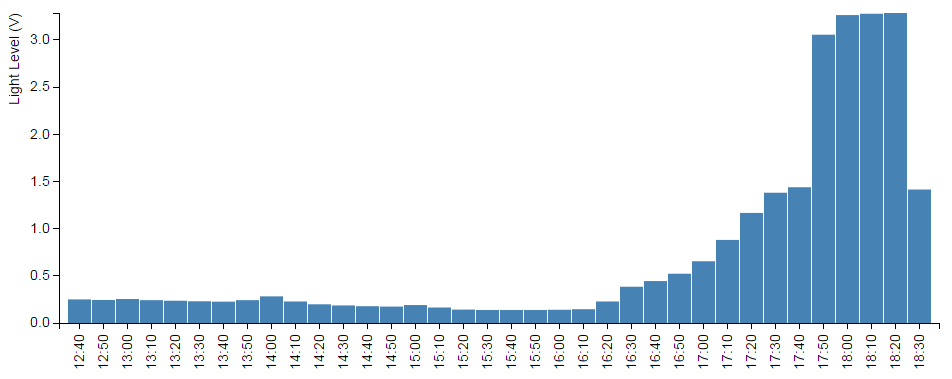

We will present the data by creating a bar graph showing the light level as measured every 10 minutes for the last 6 hours.

This project has drawn on a range of sources for information. Where not directly referenced in the text, check out the Bibliography at the end of the chapter.

Measure

Hardware required

- A Raspberry Pi (huge range of sources)

- ADS1015 Analog to Digital Converter from Adafruit.

- Female to Female Dupont connector cables (Deal Extreme or build your own!)

- Photoresistor module KY-018 from Keyes.

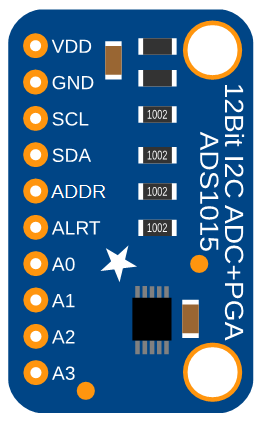

The ADS1015 Analog to Digital Converter

The ADS1015 is actually a component on our ADC board. This component is manufactured by integrated circuits manufacturer Texas Instruments. The circuit board that we’re using in the project is from Adafruit. It incorporates some interconnection circuity to make the signals as stable as practical and to provide a convenient physical interface (via header pins). The ADS1015 provides 12-bit (4096 levels) precision at up to 3300 readings per second (the rate is programmable). The board can be configured to accept four sensors of the type we will be using (single-ended), or two differential channels (which use two varying signals instead of a single signal and a ground). There is also a programmable gain amplifier built in with up to x16 gain, to help amplify smaller signals to the full range. The ADC can operate on a voltage range from 2V to 5V Which is applied to the VDD pin).

If all this sounds a bit electrickery, don’t sweat it. The aim here is to provide ourselves with enough information to get us started and if we feel like pressing on and learning more we will :-).

The ADS1015 will send the digital levels to the Pi via the I2C communications protocol. The address that this connection is made on can be changed to one of four options so you can have up to 4 ADS1015’s connected for up 16 sensor inputs!

The Light Dependant Resistor (LDR or Photoresistor) Sensor

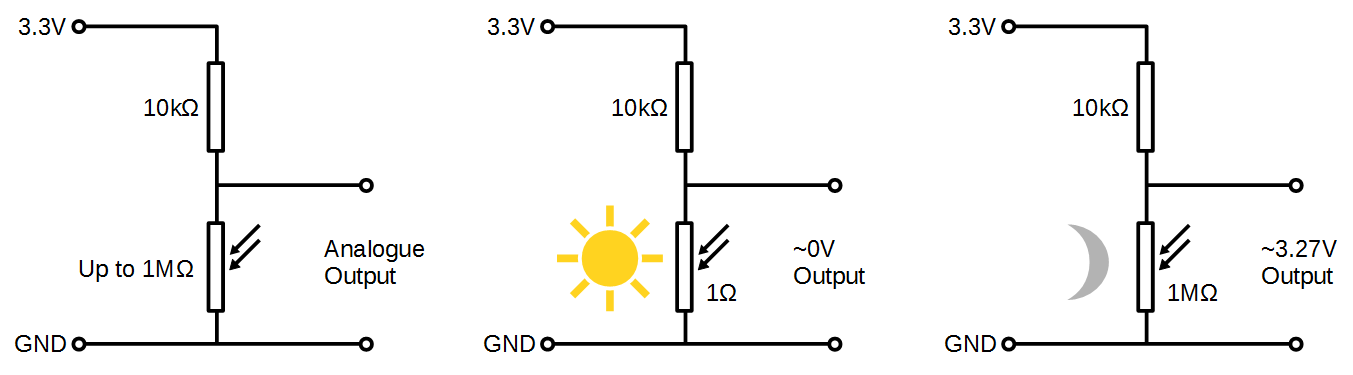

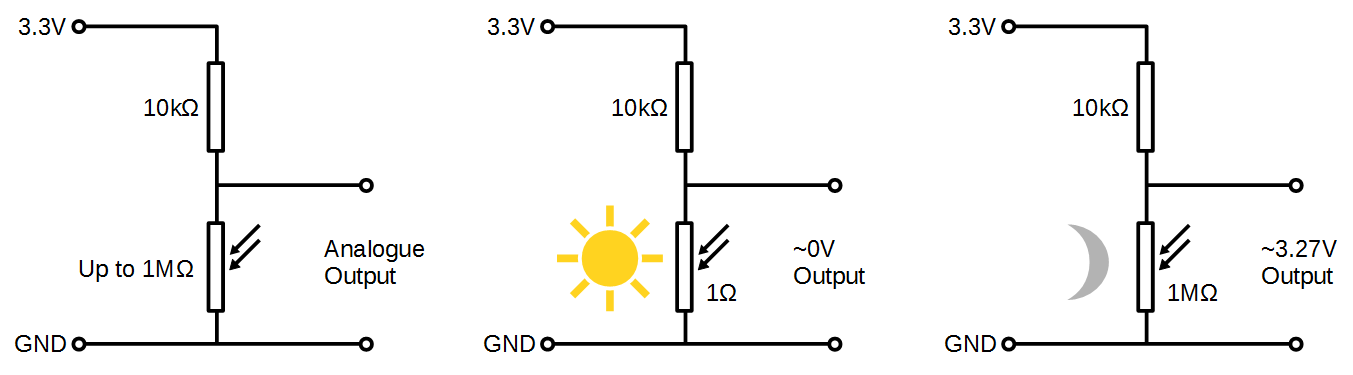

Our sensor will use an LDR to produce a variable resistance in the presence of different light levels.

In the dark, their resistance is very high, sometimes up to 1MΩ, but when the LDR sensor is exposed to light, the resistance drops dramatically, even down to a few ohms, depending on the light intensity. LDRs have a sensitivity that varies with the wavelength of the light applied and are non-linear devices.

They are widely used in cameras, solar garden lights, clocks, mini night-lights, and a variety of light control devices.

Specifications from a typical LDR show that as illumination increases, the resistance of an LDR decreases.

Light Level Resistance

Moonlight 1,000,000 Ohms

60W bulb at 1m 6,000 Ohms

Fluorescent Lighting 1,000 Ohms

Bright sunlight 1 Ohm

The Keyes KY-018 sensor board comprises an LDR and a fixed resistor with header pins for connecting the ground, the reference voltage (we will use the 3.3V from the Pi) and the sensors analog voltage output.

If we consider a simplified circuit of our sensor, the LDR in series with a fixed resistor allows the variation in resistance to develop a variation in output voltage.

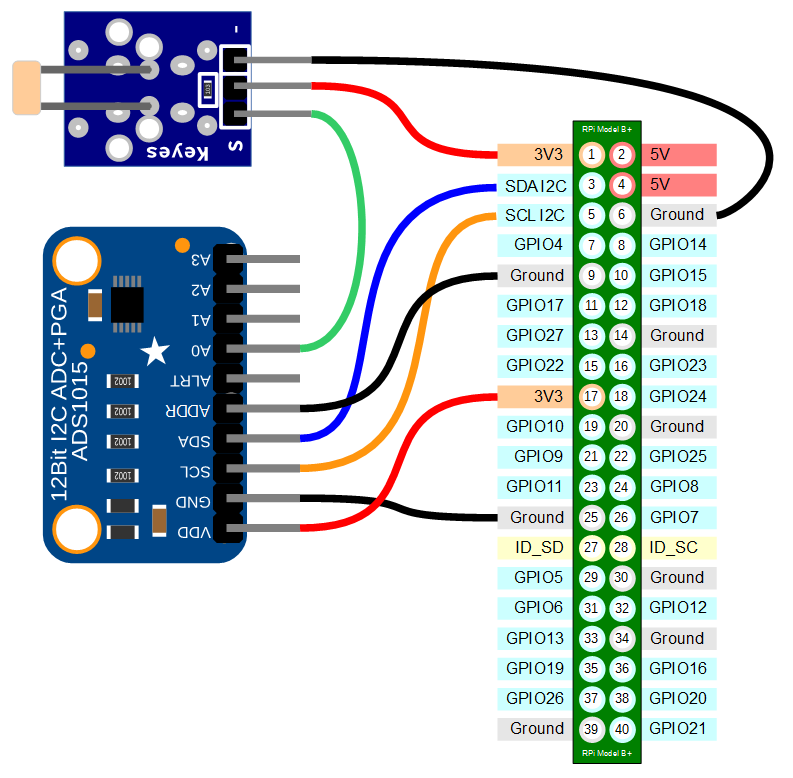

Connect

The LDR sensor board should be connected with ground pin (labelled ‘-‘) to a ground connector, the reference voltage pin (in the case of the board shown below the centre pin) to a 3.3V connector and the signal output pin (labelled ‘S’) to the A0 pin on the ADS1015 ADC.

The ADS1015 board should have the VDD pin connected to a 3.3V pin, the GND to a ground pin, the SCL pin to the SCL I2C connector on pin 5 and the SDA pin to the SDA I2C connector on pin 3 and lastly the ADDR pin should be connected to ground.

Both boards will support a connection to the ‘VDD’ and reference voltage connector of 5V, but this is not advisable for the Raspberry Pi as the resulting signal levels on the SDA connector may be higher than desired for the Pi’s input. This connection can be safely used with an Arduino board.

Connecting the sensor practically can be achieved in a number of ways. You could use a Pi Cobbler break out connector mounted on a bread board connected to the appropriate pins. But because the connection is relatively simple we could build a minimal configuration that will plug directly onto the pins using Dupont header connectors and jumper wire. The image below shows how simple this can be.

Test

Since the ADS1015 uses the I2C protocol to communicate, we need to load the appropriate kernel support modules onto the Raspberry Pi to allow this to happen.

Firstly make sure that our software is up to date

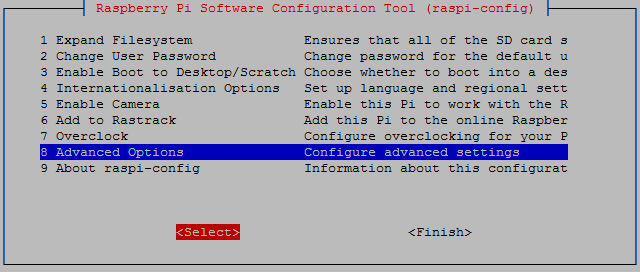

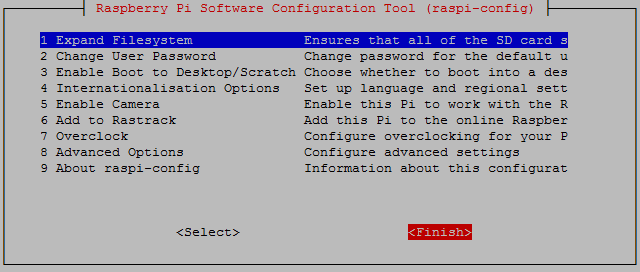

Since we are using the Raspbian distribution there is a simple method to start the process of configuring the Pi to use the I2C protocol.

We can start by running the command;

This will start the Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool.

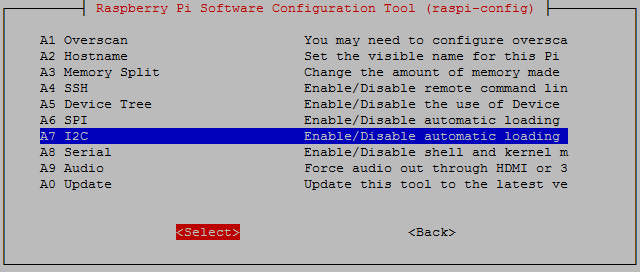

On the first page select the Advanced Options with the space bar and then tab to select

Then we select the I2C option for automatic loading of the kernel module;

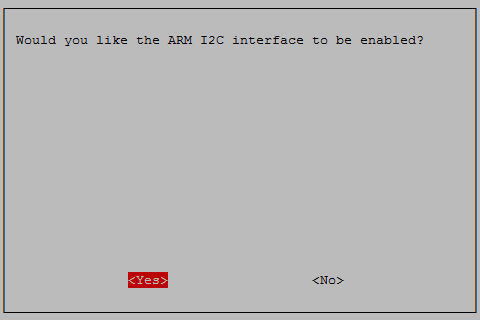

Would we like the ARM I2C interface to be enabled? Yes we would;

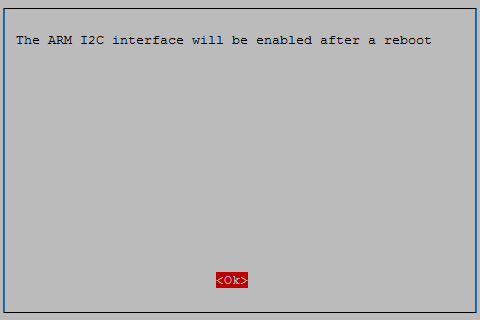

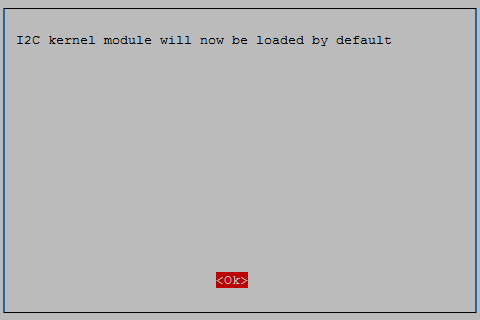

We are helpfully informed that the I2C interface will be enabled after the next reboot.

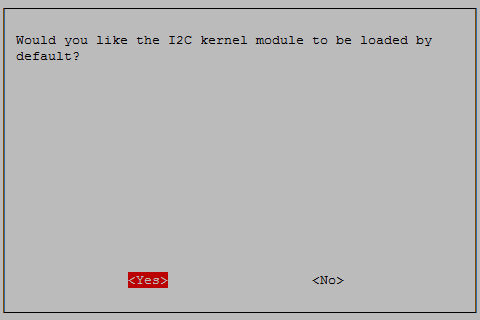

Would we like the I2C kernel module to be loaded by default? Yes we would;

We are helpfully informed that the I2C kernel module will be loaded by default after the next reboot.

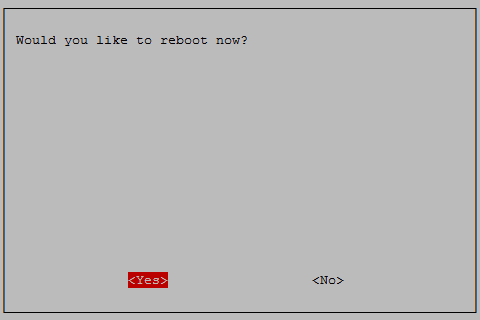

Press tab to select ‘Finish’.

And yes, we would like to reboot.

There’s still some work to do to get things sorted. We need to edit the /etc/modules file using:

Where we need to add the following two lines to the end of the /etc/modules file:

i2c-bcm2708

i2c-dev

Under some circumstances (depending on the kernel version we are using) we would also need to update the /boot/config.txt file. We can do this using;

Make sure that the following lines are in the file;

dtparam=i2c1=on

dtparam=i2c_arm=on

The we should load tools for working with I2C devices using the following command;

… and now we need to reboot to load the config.txt file from earlier

We can now check to see if our sensor is working using;

The output should look something like;

pi@raspberrypi ~ $ sudo i2cdetect -y 1

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

20: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 48 -- -- -- -- -- -- --

50: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

60: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

This shows us that we have detected our ADS1015 on address ‘48’. The ADS1015 can support four different addresses as shown on page 17 of the data sheet. The address is selected by what the ADDR (short for address!) pin on the board is connected to;

ADDR PIN ADDRESS

Ground 48

VDD 49

SDA 4A

SCL 4B

As we noted earlier, this means we can connect up to four ADS1015’s on the same I2C bus.

Now we want to install Python libraries designed to read the values from the ADS1015. The library we are going to use was designed specifically to work with the Adafruit ADS1015/ADS1115 ADCs. In carrying out this library development, Adafruit have invested a not inconsiderable amount of time and resources. In return please consider supporting Adafruit and open-source hardware by purchasing products from Adafruit!

Now we create a directory that we will use to download the Adafruit Python library (assuming that we’re starting from our home directory);

Now we will download the library into the adc directory (the following command retrieves the library from the github site);

Now that we’ve downloaded it, we can run an example program as follows

This will hopefully produce an output similar to the following;

1.558000

This is an indication of the voltage that the analog sensor is producing.

To test that the sensor is responding correctly shine a light on it and re-run the command;

With a brighter light we should have a lower voltage;

0.44000

If we remember back to our earlier diagram showing the type of connection this helps put the changes into context

At this point we have successfully read and displayed an analog signal from a sensor using the Raspberry Pi.

Record

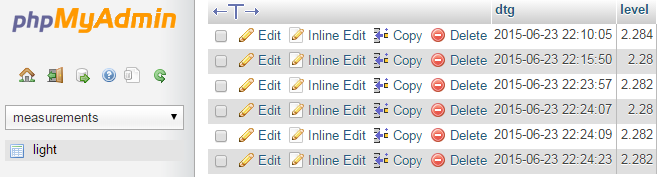

To record this data we will use a Python program that connects to our sensor via the ADC, reads the value of voltage and writes that value into our MySQL database. At the same time a time stamp will be added automatically.

This code will record the value when executed, but we will need to edit the crontab to allow the value to be recorded continuously (at a set interval).

Database preparation

First we will set up our database table that will store our data.

Using the phpMyAdmin web interface that we set up, log on using the administrator (root) account and select the ‘measurements’ database that we created as part of the initial set-up.

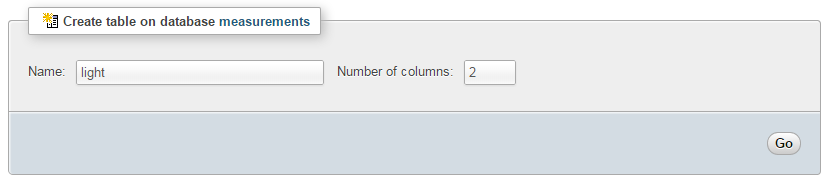

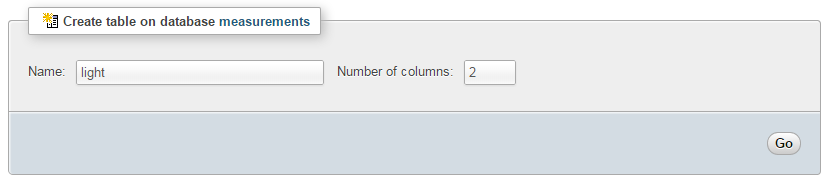

Enter in the name of the table and the number of columns that we are going to use for our measured values. In the screenshot above we can see that the name of the table is ‘light’ and the number of columns is ‘2’.

We will use two columns so that we can store the voltage that corresponds to the light level and the time it was recorded (‘dtg’).

Once we click on ‘Go’ we are presented with a list of options to configure our table’s columns. Don’t be intimidated by the number of options that are presented, we are going to keep the process as simple as practical.

For the first column we can enter the name of the ‘Column’ as ‘dtg’ (short for date time group) the ‘Type’ as ‘TIMESTAMP’ and the ‘Default’ value as ‘CURRENT_TIMESTAMP’. For the second column we will enter the name ‘temperature’ and the type is ‘FLOAT’. For the third column we will enter the name ‘pressure’ and the type is also ‘FLOAT’.

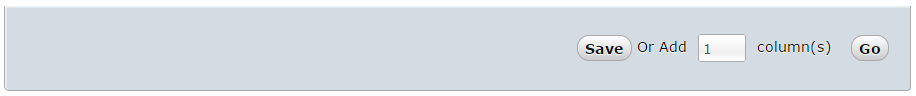

Scroll down a little and click on the ‘Save’ button and we’re done.

Record the readings

To utilise the Python libraries and to run our Python script from our home directory we will want to change into the the directory where the library is and copy the appropriate file from the downloaded directory to our home directory then we can change back into our home directory;

The following Python code is a script which allows us to check the state of our LDR sensor, return the value for voltage that corresponds to the amount of light (via the ADC) and writes that value to our database.

The full code can be found in the code samples bundled with this book (adc.py).

#!/usr/bin/python

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

import MySQLdb as mdb

import logging

from Adafruit_ADS1x15 import ADS1x15

# Setup logging

logging.basicConfig(filename='/home/pi/adc_error.log',

format='%(asctime)s %(levelname)s %(name)s %(message)s')

logger=logging.getLogger(__name__)

# Function for storing readings into MySQL

def insertDB(level):

try:

con = mdb.connect('localhost',

'pi_insert',

'xxxxxxxxxx',

'measurements');

cursor = con.cursor()

sql = "INSERT INTO light(level) \

VALUES ('%s')" % \

(level)

cursor.execute(sql)

sql = []

con.commit()

con.close()

except mdb.Error, e:

logger.error(e)

# Get readings from sensor and store them in MySQL

ADS1015 = 0x00 # 12-bit ADC

gain = 4096 # +/- 4.096V

sps = 250 # 250 samples per second

# Initialise the ADC

adc = ADS1x15(ic=ADS1015)

# Read channel 0 in single-ended mode using the settings above

level = adc.readADCSingleEnded(0, gain, sps) / 1000

insertDB(level)

This script can be saved in our home directory (/home/pi) as adc.py and can be run by typing;

Once the command is run we should be able to check our MySQL database and see an entry for the times that the sensor was checked along with the corresponding level readings.

Code Explanation

The script starts by importing the modules that it’s going to use for the process of reading and recording the measurements;

import MySQLdb as mdb

import logging

from Adafruit_ADS1x15 import ADS1x15

Then the code sets up the logging module so that any failures in writing information to the database are written to the file /home/pi/adc_error.log.

logging.basicConfig(filename='/home/pi/adc_error.log',

format='%(asctime)s %(levelname)s %(name)s %(message)s')

logger=logging.getLogger(__name__)

In the following function where we are getting our reading or writing to the database we write to the log file if there is an error. Otherwise it will accept value of level and write it to our database.

def insertDB(level):

try:

con = mdb.connect('localhost',

'pi_insert',

'xxxxxxxxxx',

'measurements');

cursor = con.cursor()

sql = "INSERT INTO light(level) \

VALUES ('%s')" % \

(level)

cursor.execute(sql)

sql = []

con.commit()

con.close()

except mdb.Error, e:

logger.error(e)

Which brings us to the main part of our code;

ADS1015 = 0x00 # 12-bit ADC

gain = 4096 # +/- 4.096V

sps = 250 # 250 samples per second

adc = ADS1x15(ic=ADS1015)

level = adc.readADCSingleEnded(0, gain, sps) / 1000

insertDB(level)

First we declare the variables that we will use when collecting our data. We set the model number of the ADS1x15 we are using to ‘0x00’ to correspond to the ADS1015. The we can set the amount of gain (gain = 4096) and the number of samples per second the ADC will carry out (sps = 250). These are the default values that are found in the sample program and while there is a wide range of options available depending on our application, in this case the default will be adequate.

Then we initialise the ADC (adc = ADS1x15(ic=ADS1015)) then read in our level using the declared parameter values (level = adc.readADCSingleEnded(0, gain, sps) / 1000).

Finally we call the function to insert the value into the database (insertDB(level)).

It’s a fairly simple block of code that is made simple by virtue of the work that has been put into the associated libraries from Adafruit.

Recording data on a regular basis with cron

While our code is a thing of simple elegance, it only records each time it is run.

What we need to implement is a schedule so that at a regular time, the program is run. This is achieved using cron via the crontab. While we will cover the requirements for this project here, you can read more about the crontab in the Glossary.

To set up our schedule we need to edit the crontab file. This is is done using the following command;

Once run it will open the crontab in the nano editor. We want to add in an entry at the end of the file that looks like the following;

*/10 * * * * /usr/bin/python /home/pi/adc.py

This instructs the computer that every 10 minutes we will run the command /usr/bin/python /home/pi/adc.py (which if we were at the command line in the pi home directory we would run as python adc.py, but since we can’t guarantee where the script will be running from, we are supplying the full path to the python command and the adc.py script.

Save the file and the computer will start running the program on its designated schedule and we will have level entries written to our database every 10 minutes.

Job done! We’re measuring and recording our analog sensor!

Explore

To explore our light level data we will use a web based graph that shows the voltage level that has come from our ADC as bars on a bar graph.

The graph will be drawn using the d3.js JavaScript library and the data will be retrieved via a PHP script that queries our MySQL database.

The astute reader will probably be thinking “Why don’t we just use a line graph similar to the one in the simple temperature measurement project?”. That would be a very good question. The answer is that you already know how to make a simple line graph, but bar graphs are still a mystery! So read on…. (but make a line graph as well)

The Code

The following code is a PHP file that we can place on our Raspberry Pi’s web server (in the /var/www directory) that will allow us to view the last 6 hours of data in 10 minute blocks.

The full code can be found in the code samples bundled with this book (adc-bar.php).

<?php

$hostname = 'localhost';

$username = 'pi_select';

$password = 'xxxxxxxxxx';

try {

$dbh = new PDO("mysql:host=$hostname;dbname=measurements",

$username, $password);

/*** The SQL SELECT statement ***/

$sth = $dbh->prepare("

SELECT * FROM (

SELECT `dtg` AS date,

`level` AS value

FROM `light`

ORDER BY date DESC

LIMIT 0,36

) sub

ORDER BY date ASC

");

$sth->execute();

/* Fetch all of the remaining rows in the result set */

$result = $sth->fetchAll(PDO::FETCH_ASSOC);

/*** close the database connection ***/

$dbh = null;

}

catch(PDOException $e)

{ echo $e->getMessage(); }

$json_data = json_encode($result);

?><!DOCTYPE html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<head>

<style>

.axis {

font: 14px sans-serif;

}

.axis path,

.axis line {

fill: none;

stroke: #000;

shape-rendering: crispEdges;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<script src="http://d3js.org/d3.v3.min.js"></script>

<script>

var margin = {top: 20, right: 20, bottom: 70, left: 60},

width = 960 - margin.left - margin.right,

height = 400 - margin.top - margin.bottom;

// Parse the date / time

var parseDate = d3.time.format("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S").parse;

// specify the scale/range for each dimension

var x = d3.scale.ordinal().rangeRoundBands([0, width], .05);

var y = d3.scale.linear().range([height, 0]);

// axis formatting

var xAxis = d3.svg.axis()

.scale(x)

.orient("bottom")

.tickFormat(d3.time.format("%H:%M"));

var yAxis = d3.svg.axis()

.scale(y)

.orient("left")

.ticks(10);

// setup the svg area

var svg = d3.select("body").append("svg")

.attr("width", width + margin.left + margin.right)

.attr("height", height + margin.top + margin.bottom)

.append("g")

.attr("transform",

"translate(" + margin.left + "," + margin.top + ")");

// Get the data

<?php echo "data=".$json_data.";" ?>

// wrangle the data into the correct formats and units

data.forEach(function(d) {

d.date = parseDate(d.date);

d.value = +d.value;

});

// Scale the range of the data

x.domain(data.map(function(d) { return d.date; }));

y.domain([0, d3.max(data, function(d) { return d.value; })]);

// Add the X Axis

svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "x axis")

.attr("transform", "translate(0," + height + ")")

.call(xAxis)

.selectAll("text")

.style("text-anchor", "end")

.attr("dx", "-.8em")

.attr("dy", "-.35em")

.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)" );

// Add the Y Axis and the Y axis label

svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "y axis")

.call(yAxis)

.append("text")

.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)")

.attr("y", -50)

.attr("dy", ".71em")

.style("text-anchor", "end")

.text("Light Level (V)");

// Add the bars

svg.selectAll("bar")

.data(data)

.enter().append("rect")

.style("fill", "steelblue")

.attr("x", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("width", x.rangeBand())

.attr("y", function(d) { return y(d.value); })

.attr("height", function(d) { return height - y(d.value); });

</script>

</body>

This graph contains some of the common elements that what we have explored in the single temperature measurement project. However, in this code we introduce the concept of using filled rectangles to form a bar graph.

The code will automatically try to collect 36 data points from a data set that is recording a value every 10 minutes. As a result this will present 6 hours worth of data.

PHP

The PHP block at the start of the code is mostly the same as our example code for our single temperature measurement project. The significant difference however is in the select statement.

SELECT * FROM (

SELECT `dtg` AS date,

`level` AS value

FROM `light`

ORDER BY date DESC

LIMIT 0,36

) sub

ORDER BY date ASC

The query only collects two columns of values. The Date Time Group (date) and the light level (level). The major difference in this query is that it has one query nested inside another.

This query…

SELECT `dtg` AS date,

`level` AS value

FROM `light`

ORDER BY date DESC

LIMIT 0,36

…. is wrapped in this query.

SELECT * FROM (

subquery

) sub

ORDER BY date ASC

This might seem slightly unusual, but it is done so that we can select the last 36 data points and arrange those points from oldest to newest.

The subquery (the nested one) selects the 36 points we want and by ordering them by date in descending (DESC) order we make sure we have the latest ones. But then they would be in an order that if we were to plot them they would appear to go from newest to oldest in our graph. So what we do is wrap that query in parentheses and give it an alias (sub) and then we select all of those results and order them by date ascending (ASC). It seems a little ‘hacky’ and there would be alternative ways to do it either in PHP or JavaScript, but it has to happen somewhere, so there it is. Any interested readers who want to suggest different avenues please forward them through and I will publish them here with suitable attribution :-).

CSS (Styles)

The styles that are applied to the elements of the graphic in the CSS area are all done for the axes.

.axis {

font: 14px sans-serif;

}

.axis path,

.axis line {

fill: none;

stroke: #000;

shape-rendering: crispEdges;

}

JavaScript

The code has very similar elements to our single temperature measurement script and comparing both will show us that we are doing similar things in the code.

The things that are for all intents the same as the single temperature code are;

- Setting up the margins

- Declaring the

parseDatefunction - Setting the scales/ranges

- Formatting the axes

- Setting up the SVG area

- Loading the data and

- Wrangling the data into the correct format

- Scaling the range of the data

There are only three blocks of code left and two of them are adding the X and Y axes. The last is adding the bars themselves, so the code is pretty darned similar. However, those three blocks are a little different, so let’s describe what’s going on;

Firstly we add the X axis;

svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "x axis")

.attr("transform", "translate(0," + height + ")")

.call(xAxis)

.selectAll("text")

.style("text-anchor", "end")

.attr("dx", "-.8em")

.attr("dy", "-.35em")

.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)" );

This is placed in the correct position .attr("transform", "translate(0," + height + ")") and the text is positioned (using dx and dy) and rotated (.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)" );) so that it is aligned vertically.

Then when add the Y axis and its label;

svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "y axis")

.call(yAxis)

.append("text")

.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)")

.attr("y", -50)

.attr("dy", ".71em")

.style("text-anchor", "end")

.text("Light Level (V)");

We also move the rotated text for the label to an appropriate position using y attribute.

At first the rotation and movement of text elements can seem confusing. In this case it’s easy to see the rotation by 90 degrees (.attr("transform", "rotate(-90)")), but the subsequent translation in the y direction (.attr("y", -50)) actually ends up moving the text in the x direction. This is because the rotate function call has also rotated our axes for the text. Therefore where a movement would have been upwards, after a rotation by -90 degrees, it is now to the left.

For more information on manipulating text elements with D3 check out this section from D3 Tips and Tricks.

Lastly we add the code that appends the bars;

svg.selectAll("bar")

.data(data)

.enter().append("rect")

.style("fill", "steelblue")

.attr("x", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("width", x.rangeBand())

.attr("y", function(d) { return y(d.value); })

.attr("height", function(d) { return height - y(d.value); });

This block of code creates the bars (selectAll("bar")) and associates each of them with a data set (.data(data)).

We then append a rectangle (.append("rect")) with values for x/y position and height/width as configured in our earlier code.

And there we have it. Our temperature and pressure being read and presented in a stylish dual line graph.

If you want a closer explanation for this piece of code, download a copy of D3 Tips and Tricks for this and a whole swag of other information.

Bibliography

RPi and I2C Analog-Digital Converter (OpenLabTools)

ADS1015 12-Bit ADC - 4 Channel with Programmable Gain Amplifier(Adafruit)

ADS1015 datasheet (Adafruit)

Adafruit 4-Channel ADC Breakouts (Adafruit Learning System)

Analog Sensors On The Raspberry Pi Using An MCP3008 (Matt, raspberrypi-spy.co.uk)

Analog Input Board for the Espiresso Pressure Sensor (int03.co.uk)

Arduino KY-018 Photo resistor module (TkkrLab)

Shenzhen KEYES DIY Robot co., Ltd

Light dependant resister datasheet (Sunroom Technologies)