Chapter 4 - Accomplishing Sustainable Development Tasks in the Technotope

4.1 - What next in Societal Portfolios: Transition Planning?

4.2 - An abstract Partner Journey

4.3 - Values for a Societal Agenda

4.4 - Stakeholders, Initiatives & Reporting

4.5 - Access characteristics of resources

4.6 - Digital Principles

4.7 - The Principles of Doing Development Differently

4.8 - Work systems and drivers for change

4.9 - Case materials

To Part I (Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4) _ II (5 - 6 - 7) _ III (8 - 9 - 10 - 11 - 12 - (no 13)) _ IV (14 - 15) _ V (Annexes) _ VI (References)

4.1 - What next in Societal Portfolios: Transition Planning?

It is the author’s hope that the United Nations will sooner or later adopt and endorse the Societal Architecture as an Unsollicited Proposal (USP), (this is an exception to the public initiation of infrastructure public-private partnerships). Such an adoption would facilitate and accelerate the growth of the Societal Architecture and its subsequent phases: Opportunities and Solutions, Transition Planning, Implementation Governance, and Architecture Change Management.

While this book is aimed at professionals involved in portfolios, programs and projects in both the public and private sectors, I have also produced reference works for the general public in which #tagcoding hashtags are defined for all topics in relation to which public or private portfolios, programs and projects might seek change or communication.

The #tagcoding guide is available in e-book versions in English, French, Spanish and Tagalog, and online versions in several other languages, including Arabic, Simplified Chinese, Swahili, Russian, Japanese, Hindi, Telugu, German, Ilonggo and Dutch. #tagcoding supports communications in social media platforms for all kinds of initiatives in global to local social portfolios.

When it comes to communication in the public sphere, the principles of Societal Architecture lead to the creation of distinctive communication channels where everyone can publish and everyone can consult. A channel is needed for every important topic at every level of scope and in every language. To create such a communication infrastructure, #tagcoding hashtags play a key role.

One of the purposes of this book is to recruit practitioners in a Societal Architecture Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership.

4.2 - An Abstract Partner Journey

This content is not available in the sample book. The book and its extras can be purchased from Leanpub at https://leanpub.com/socarch.

4.3 - Values for a Societal Agenda

But what problems might a (democratic) society or one of its members want to solve?

To answer this question, one must first consider what a society values.

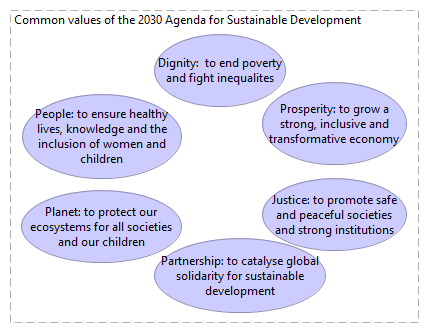

The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet (Synthesis report of the Secretary General on the post-2015 sustainable development agenda, December 4, 2014) proposes six values as essential elements for delivering on the sustainable development goals:

- Dignity: to end poverty and fight inequalities

- People: to ensure healthy lives, knowledge and the inclusion of women and children

- Prosperity: to grow a strong, inclusive and transformative economy

- Planet: to protect our ecosystems for all societies and our children

- Justice: to promote safe and peaceful societies and strong institutions

- Partnership: to catalyse global solidarity for sustainable development

The figure below shows these values in their “official” graphical form.

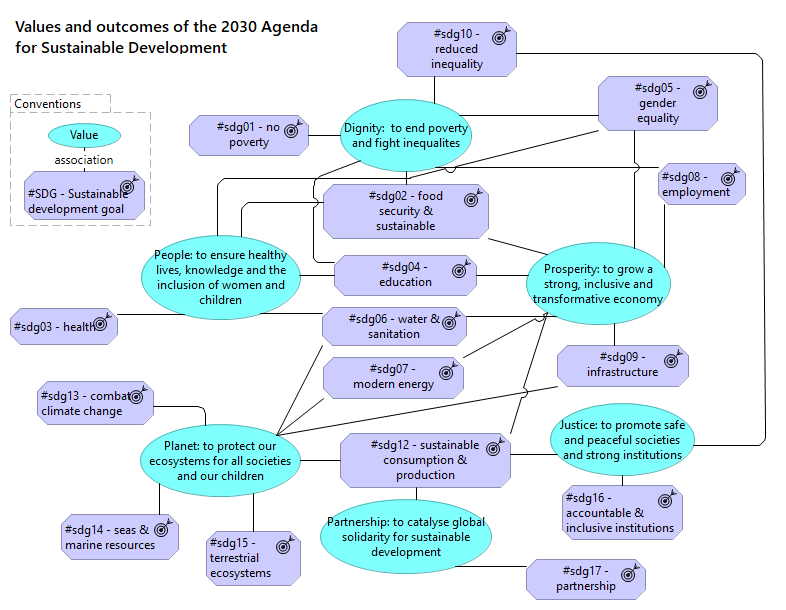

A second figure shows the values using the Archimate value model element.

This second figure is less attractive to the eye, but the advantage of it is that the model elements are captured in an Archimate modeling tool that allows us to use the element in many more views.

One of those other views is the one in which the association between the values and the sustainable development goals are depicted.

4.4 - Stakeholders, Initiatives & Reporting

The organizational or external roles that take responsibility for object system operations and reflective activities and assets are also called stakeholders. In portfolios, programs, and project studies, specific tasks are performed to support communication with these stakeholders. In addition, these stakeholders will have specific interests regarding the study; they may have a say in the go/no go decision regarding the initiative and study.

In an enterprise architecture described according to the ArchiMate framework, the stakeholders (for the enterprise architecture against which the service solution will be positioned) are included in the motivation extension. The rationale for their involvement will often be related to their role in the business collaboration to be supported by the service solution.

Hands-on users (of the product for which requirements are being collected) are addressed as part of the Active Structure aspect: the Business Actor would include the Stakeholder descriptive elements and the Business Role would include the User Role.

Stakeholders of the stakeholder class “Interfacing Technology” are called “Application Components” and are described as part of the Application layer of the framework; the rationale for their involvement will often be related to their role in an application collaboration between “Services”.

In Chapter 14 - Agents we gather insights on these stakeholders from global to local societal portfolios, stakeholders that will drive the talent explosion for sustainable development.

- Citizens and households

- Global Partnership

- Firms

- National Government

- Local Authorities

- Schools

- UN Country Teams

- Publishers and right holders

- Libraries

- Aid and international organizations

The global societal portfolios considered in detail are:

- The Global Tax Portfolio

- The Global Content Portfolio (to be added)

Since both portfolios are relevant for all listed stakeholders, we pay special attention to stakeholders who are beneficiaries of several initiatives at the same time.

The governance activity determines the outcomes of the object system (of projects) that need to be monitored and evaluated. Whenever a redesign or change is proposed, it must be evaluated in terms of its impact on system outcomes as well as its fit with other initiatives.

You cannot set indicators before you set outcomes, because it is the outcomes-not the indicators-that will ultimately produce the benefits.

Corporate triple bottom line reporting is being harmonized through the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The GRI distinguishes between three categories of indicators to achieve more aligned reporting for companies on results in the context of global challenges:

- economic: The economic dimension of sustainability addresses an organization’s direct and indirect impacts on the economic circumstances of its stakeholders and on economic systems at local, national and global levels.

- environmental: The environmental dimension of sustainability concerns an organization’s impacts on living and non-living natural systems, including ecosystems, land, air and water.

- social: The social dimension of sustainability concerns an organization’s impact on the social systems in which it operates. Social performance can be measured by analyzing the organization’s impact on stakeholders at the local, national, and global levels. In some cases, social indicators affect the organization’s intangible assets, such as its human capital and reputation.

Indicators are only relevant if they measure against a goal. Thus, the measurement of indicators will show the progress made towards achieving the intended goals. Decision makers and stakeholders are in a position to make the intended outcomes of the object system as explicit as possible. Articulating outcomes is critical to achieving stakeholder ownership.

Indicators are the quantitative or qualitative variables that provide a simple and reliable means of measuring achievement, reflecting changes associated with an intervention, or helping to assess the performance of an organization or object system in relation to the stated outcome. Indicators are needed to monitor progress with respect to inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and goals. In complex systems, progress needs to be monitored at all levels of the system to provide feedback on areas of success and areas that may need improvement.

For each of the stakeholders affected by the expected outcome of a portfolio, progress reports should identify the relevant aspects.

For each of the organization’s asset components (see “Assets” in Figure 1.4), progress reports should identify the changes in the component. For example, consider the job descriptions for employees, performance measurement requirements, reporting activities, etc.

4.5 - Access characteristics of resources

This content is not available in the sample book. The book and its extras can be purchased from Leanpub at https://leanpub.com/socarch.

4.6 - Digital Principles

The principles of digital capability have had little visibility in the description of the decision-making context and activities.

Yet digital capabilities are among the defining characteristics of our time. So what is their impact?

To understand this impact, we look briefly at the Principles for Digital Development, which have been coined by an international consortium and are widely applied.

A Societal Architecture is proposed as a coherent way to apply these digital principles across a wide range of initiatives.

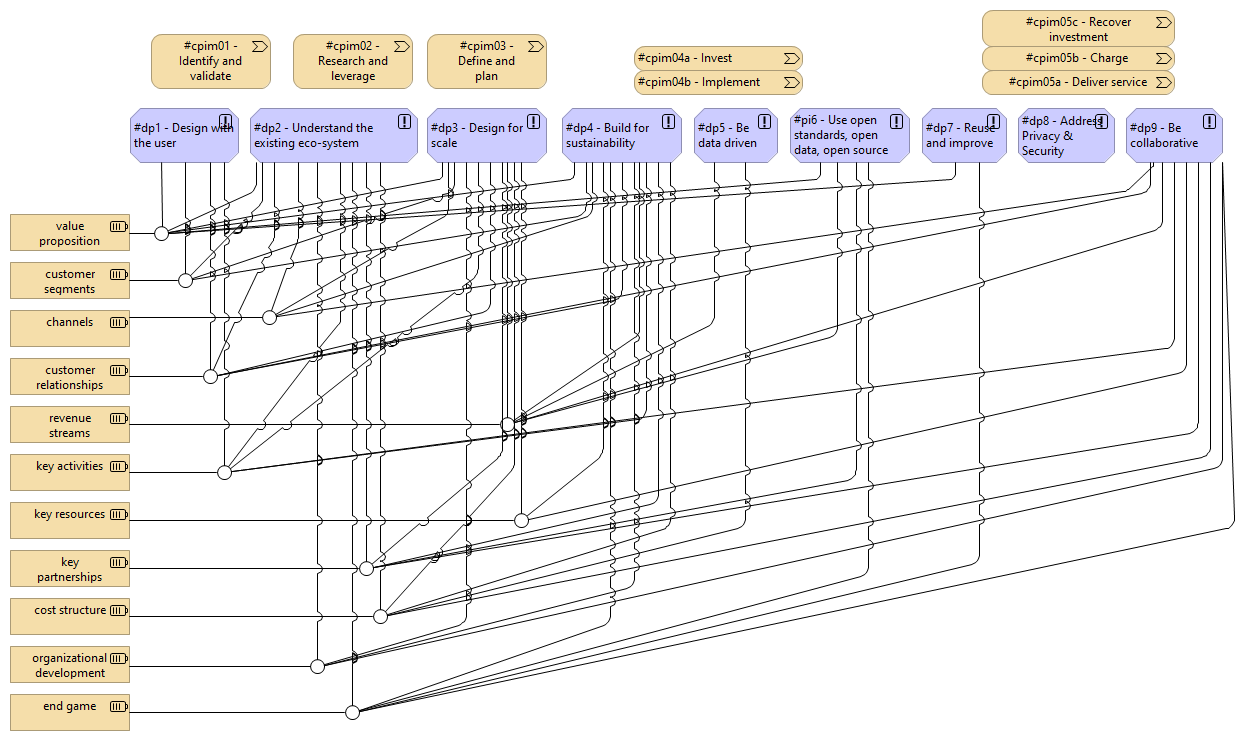

Figure 4.9 illustrates how the Digital Capability Principles relate to the value streams of CPIM and to the resources that make up the Business Model Sustainability Toolkit.

A key aspect of using the Principles for Digital Development is working with models and data:

- #dp1 - Design with people

- #dp2 - Understand the existing ecosystem

- #dp3 - Design for inclusion

- #dp4 - Build for sustainability

- #dp5 - Establish people-first data practices

- #dp6 - Create open and transparent practices

- #dp7 - Share, reuse, and improve

- #dp8 - Anticipate and mitigate harms

- #dp9 - Use evidence to improve outcomes

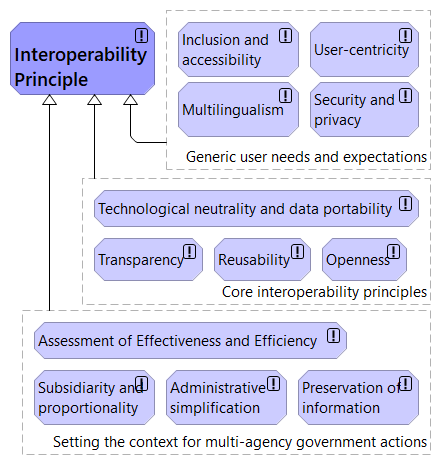

Specifically for the public sector, the European Interoperability Framework (EIF) proposes the principles shown in Figure 4.10.

Design with people

Good design starts and ends with people that will manage, use, and ideally benefit from a given digital initiative.

- To design with people means to invite those who will use or be affected by a given technology policy, solution, or system to lead or otherwise meaningfully participate in the design of those initiatives.

- In all cases, there will be more than one group of relevant stakeholders (including those who ideally benefit from the initiative and those who will maintain/administer the initiative), each of whom need to participate and engage in the initial design phase and in subsequent iterations. The specific stakeholders will need to be defined separately for each initiative.

- Initiatives can encourage meaningful participation by creating opportunities for people to innovate on top of products and services; establishing avenues for feedback and redressal that are regularly monitored and addressed; and committing to agile methods that allow for continual improvement.

Otherwise, initiatives are unlikely to gain trust of and adoption of the communities they seek to reach.

Understand the Existing Ecosystem

Understanding the existing ecosystem.

Trust starts with a thorough understanding of the dynamic cultural, social, and economic context in which you are operating.

- Digital ecosystems are defined by the culture, gender and social norms, political environment, economy, technology infrastructure and other factors that can affect an individual’s ability to access and use a technology or to participate in an initiative.

- Understanding the existing ecosystem can help determine if and how we should engage, as ecosystems can have both positive and negative dynamics.

- Through this understanding, initiatives should adapt in order to support, to the extent appropriate, existing technology, and local actors who are already working to tackle key challenges. This includes understanding existing government policies, national visions, sector policies/priorities/strategies, and efforts to expand foundational digital public infrastructure.

- This also includes understanding existing access to devices, connectivity, affordability, digital literacy, and capacity strengthening opportunities so that initiatives are designed to accommodate or strengthen these realities.

- When initiatives do not first understand the ecosystem they are operating in, it can hinder uptake, adoption, and trust. It can also lead to unintended consequences, such as exclusion, loss of trust, or reinforcement of harmful power dynamics, and putting the safety and security of stakeholders at risk.

- Digital ecosystems are fluid, multifaceted and ever-changing, requiring that digital development practitioners regularly analyze the context to check their assumptions.

Design for inclusion

Consider the full range of human diversity to maximize impact and mitigate harm.

- When leveraged intentionally and to its fullest potential, technology can overcome, rather than exacerbate, existing inequality. To design for inclusion is to seize the opportunity for digital initiatives to drive social progress by dismantling systemic barriers related to gender, disability, income, geography, and other factors.

- Regardless of the size of their intended audience, technology initiatives should be designed to be accessible and usable for a diverse range of people, including those with disabilities, low digital literacy, those who speak different languages, who face obstacles to device access/affordability/connectivity, and those from different cultural backgrounds.

- This can be achieved by adopting iterative methodologies (such as agile) and by leveraging redressal systems to quickly identify – and address – challenges that negatively impact certain groups of people.

- Designing for inclusion can include considering how the benefits of an initiative accrue even to those who are not online.

- Designing for inclusion requires considering the opportunity to strengthen capacity for those who do not have the skills or tools necessary to benefit from a given initiative, as well as the affordability of devices and services (in the short and long-term).

Without following inclusive practices in the design of digital initiatives, we risk amplifying existing inequalities, creating unforeseen harms, and excluding segments of the population from participation and opportunity.

Build for Sustainability

Build for the long-term by intentionally addressing financial, operational, and ecological sustainability.

- Sustainability here is defined broadly to account for financial, operational, and ecological sustainability, all of which are important to avoid service disruptions for people.

- Building for sustainability means thinking about leveraging the inherent scalability of digital technology solutions early on. Decide on the desired scale of your initiative and prepare accordingly from the start.

- Building for sustainability means presenting the long-term cost of ownership–both technology licenses, operations and maintenance, capacity building, etc.–and clearly indicating how initiatives will be paid for in the future, by donors, host governments, or commercial means.

- Ecological sustainability requires considering an initiative, solution, or system’s potential to help people and communities adapt to the changing climate. At the same time, they should seek to minimize the environmental impact of any initiative, solution, or system, particularly the CO2 emissions generated by any hardware or software during the entire lifecycle from production to disposal.

Building for sustainability does not mean that all products, services, or policies will last forever. Optimizing for sustainability may result in consolidating services, transferring knowledge, software, and/or hardware to a new initiative, planning for the secure transfer (or deletion) of data at the end of a project, or helping clients to transition to a new, more relevant product or service.

Establish people-first data practices

Establish people-first data practices

People-first data practices prioritize transparency, consent, and redressal while allowing people and communities to retain control of and derive value from their own data.

- Digital services and initiatives generate, rely on, and/or use data derived from people or their assets. This principle emphasizes the need to avoid collecting data that is used to create value (financial or otherwise) for a company or organization, without delivering any direct value back to those people from whom the data is derived.

- It is thus critical to consider people and to put their rights and needs first when collecting, sharing, analyzing, or deleting data. In this context, ‘people’ includes those who directly interact with a given service, those whose data was obtained through partners, and those whose are impacted by non-personal datasets (such as geospatial data.)

- When collecting data, it is important to consider and follow relevant data standards and guidelines set at the international, regional, national, or local level.

- People-first data practices include ensuring that people can understand and control how their data is being used; obtaining explicit and informed consent from people before collecting, using, or sharing their data; and investing in people’s capacity to navigate the tools, redressal systems, and data practices.

- People-first data practices also include sharing data back with people, so that they have agency to use this data as they see fit, and providing access to individual, secure data histories that people can easily move from one service provider to the next.

When this principle is violated, people may be subject to undue and unpredictable harms, stemming from data breaches, exclusion from services, or discrimination based on their digital data trail.

Create open and transparent practices

Create open and transparent practices

Effective digital initiatives establish confidence and good governance through measures that promote open innovation and collaboration.

- To establish and maintain trust in the digital ecosystem, it is necessary for all people—whether or not they are directly impacted by a given initiative—to have confidence in digital policies, services, and systems and the associated data handling. This confidence is nurtured through open and transparent practices, which in turn foster accountability.

- Open and transparent practices can include but are not limited to: clear and accountable governance structures that define roles and responsibilities; open and proactive communication, decisions, policies, and practices; mechanisms that allow stakeholders to provide feedback, ask questions, and raise concerns; and quick and transparent responses to feedback.

- In terms of technical design, open and transparent practices can include the use of agile methodologies, open standards, open data, open source, and open innovation.

When organizations do not prioritize transparency and openness, it results in a lack of or loss of trust. Trust is critical to encourage participation, and without it, people will rationally choose to avoid the risks associated with engaging with digital services and sharing their data – thus foregoing any potential benefits.

Share, reuse, and improve

Build on what works, improve what works, and share so that others can do the same.

- Avoid innovation for the sake of innovation

- To share, reuse, and improve is, in essence, to collaborate. Collaboration is essential to achieving our shared vision of a more equitable world. We have the most impact when we share information, insights, strategies, and resources across silos related to geographies, focus areas, and organizations. By sharing, reusing, and improving existing initiatives, we pool our collective resources and expertise, and avoid costly duplication and fragmentation. Ideally, this leads to streamlined services for people.

- This can apply to technology products, services, research, or policies.

- This requires organized and accessible documentation, and is greatly facilitated by adopting open standards, building for interoperability and extensibility; using open source software; and contributing to open source communities.

- Following this principle can save time and money, promote collaboration and the sharing of knowledge, and lead to better products and services through continuous improvement.

Forgoing this principle in favor of do-it-alone approaches leads to wasted resources (particularly problematic in the case of public donor funds), limited innovation and improvement, and undue burden on people that can hinder trust and participation.

Anticipate and mitigate harms

Harm is always possible when it comes to technology. To avoid negative outcomes, plan for the worst while working to create the best outcomes.

- Technology is now part of our everyday lives: no program or technology solution operates in isolation. Therefore, to live up to the commitment to do no harm, policymakers and practitioners need to anticipate and work to mitigate harms, even those that originate outside of a given initiative.

- There are a number of potential harms that may arise from any given digital initiative, and any list offered here will prove to be insufficient. Examples of harms include enabling digital repression (including illegal surveillance and censorship); exacerbating existing digital divides associated with, for example, disability, income, or geographic location; technology-facilitated gender based violence; undermining local civil society and private sector companies; amplifying existing, harmful, social norms; and creating new inequities.

- While harms are present with all technology, these harms are particularly relevant, and the impacts are less known, when it comes to machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI).

- Harm mitigation is context-specific, and requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates technical, regulatory, policy, and institutional safeguards. Effective harm mitigation takes a long-term approach, considering how current challenges and inequities will be amplified by unknown developments.

Without these types of safeguards, specific groups of people may decide to disengage or systems may be used to intentionally target certain groups of people, undermining all sustainable development goals.

Use evidence to improve outcomes

Use evidence to improve outcomes

Evidence drives impact: continually gather, analyze and use feedback.

- Over time, good practices in understanding monitoring and evaluation of technology initiatives have evolved to emphasize outcomes on people and communities, rather than just access and usage.

- To understand outcomes for people and communities, it is necessary to use a variety of methods – both technology-enabled and analogue – to gather, analyze, and use feedback to get a holistic view of the impact of technology on people and communities.This also includes providing redressal channels for people to submit feedback and complaints, which are regularly monitored, addressed, and analyzed.

- Understanding outcomes is critical to an agile or iterative design approach through which digital policies, systems, and solutions are continually updated and improved.

- Involve people in the design and implementation of the monitoring and measuring of outcomes as well, so that the outcomes being measured are relevant and meaningful to them.

Otherwise, initiatives may meet efficiency and outreach goals, but fail to see lack of impact, harmful impacts, or opportunities to improve positive outcomes on people and communities.

4.7 - The Principles of Doing Development Differently

Source: The Doing Development Differently Manifesto:

- (#ddd1) - Focus on solving local problems: Initiatives focus on solving local problems that are discussed, defined, and refined by local people in an ongoing process.

- (#ddd2) - Legitimized at all levels and locally owned: Initiatives are legitimized at all levels (political, managerial and social), building ownership and momentum throughout the process to be ‘locally owned’ in reality (not just on paper).

- (#ddd3) - Local conveners mobilize everyone with a stake in progress: Initiatives work through local conveners who mobilize all those with a stake in progress (in both formal and informal coalitions and teams) to tackle common problems and bring about relevant change.

- (#ddd4) - Rapid cycles of planning, action, reflection, and revision: Initiatives link design and implementation through rapid cycles of planning, action, reflection and revision (drawing on local knowledge, feedback and energy) to promote learning from both success and failure.

- (#ddd5) - Manage risk by making ‘small bets’: Initiatives manage risk by making “small bets”: pursuing activities with promise and dropping others.

- (#ddd6) - Foster real results: Initiatives promote real results - real solutions to real problems that have real impact: they build trust, empower people, and promote sustainability.

These principles suggest the use of multiple iterations in development initiatives.

4.8 - Work system and drivers for change

This content is not available in the sample book. The book and its extras can be purchased from Leanpub at https://leanpub.com/socarch.

4.9 - Case materials

This book is ambitious and aims to prove that broad principles can indeed be linked to interdependent decision making in a wide range of practical situations. To do this, we provide and apply models that are characteristic of the different levels of planning addressed in the Collaborative Planning and Investment Methodology (CPIM): open portfolios, programs, projects, and iterations.

After introducing the methodology in Chapter 4 and the Societal Architecture in Chapter 6 (Part 2 of the book), we are ready to illustrate the use of models for each of the four planning levels for a number of cases:

- Planning Level 1 - Open Portfolios

- Planning Level 2 - Programs

- Planning Level 3 - Projects

- Planning Level 4 - Iterations

- Case 1 - 2030 Agenda

- Case 2 - Library Services

- Case 3 - The Gas Station Case

- Case 4 - The Port Case

The value framework for driving change in the cases is derived from the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which is also presented as a model in an open portfolio. The overall methodology includes executable models and experiments that are not elabo- rated in the current version of this e-book. For such models, we refer to simulation and programming courses and manuals, as well as platforms such as Camunda. To the cases - To the chapter

Case 1 - 2030 Agenda

In the 2030 Agenda, models at the four levels of planning are relevant to stakeholders at the different socio-technical levels. Models in portfolios are relevant to the Global Partnership, which includes national governments, local authorities, UN country teams and aid agencies and international organizations. Programs would typically involve multiple members of the Global Partnership setting rules and patterns for the landscape, as well as Schools, Publishers and Rightsholders and Libraries operating within the “regulated” landscape.

- CPIM01 - Identification and Validation in the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM02a - Scope and Variables in the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM02b - Conceptual Models and the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM02c - Executable Models for the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM02d - Experimentation and the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM03 - Define and Plan for the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM04 - Invest and Execute for the 2030 Agenda

- CPIM05 - Perform and Measure for the 2030 Agenda

Case 2 - Library Services

Library services would include works from Publishers and Rightsholders as well as digital public goods, encouraged by the global digital public goods portfolio that the Digital Public Goods Alliance manages and advocates for.

Projects and iterations would involve Citizens and Households, Schools, Publishers and Rightsholders, and Libraries.

Publishers and rightsholders could develop their own portfolio for making copyrighted works available in libraries, especially digital works.

Again, models at the four planning levels are important at the different socio-technical levels, in this case especially from meso (publishing organizations and library organizations) to micro (libraries and publishers) to pico (authors and library users).

- CPIM01 - Identification and Validation for Library Services

- CPIM02a - Scope and Variables of Library Services

- CPIM02b - Conceptual Models and Library Services

- CPIM02c - Executable Models for Library Services

- CPIM02d - Experimentation and Library Services

- CPIM03 - Define and Plan for Library Services

- CPIM04 - Invest and Execute for Library Services

- CPIM05 - Perform and Measure for Library Services

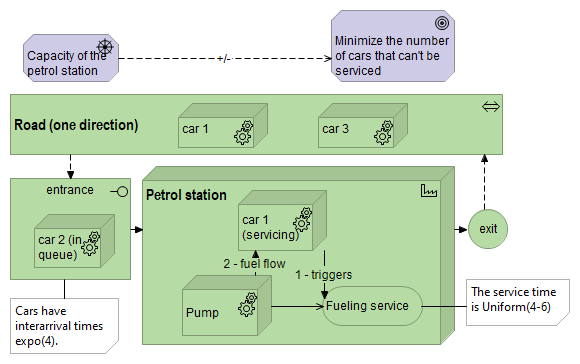

Case 3 - The Petrol Station

The owner of the petrol station has the feeling that some potential clients are leaving the station because there is no place to wait for service. But he doesn’t know to which extend this assumption is true. So he would like to know what is the influence of the capacity size of the pump on the percentage of cars leaving without being served. In the current situation, three cars at most can wait for petrol filling at the petrol pump. The cars in the queue follow a First In First Out Rule (FIFO).

This case is situated at the micro level and illustrates the possible scope of a project or iteration.

- CPIM01 - Identification and Validation at a Petrol Station

- CPIM02a - Scope and Variables in the Petrol Station Case

- CPIM02b - Conceptual Model of Petrol Station Operations

This case has been part of a course on the Simulation of Operational Processes that colleagues and me have been teaching between 2004 and 2008.

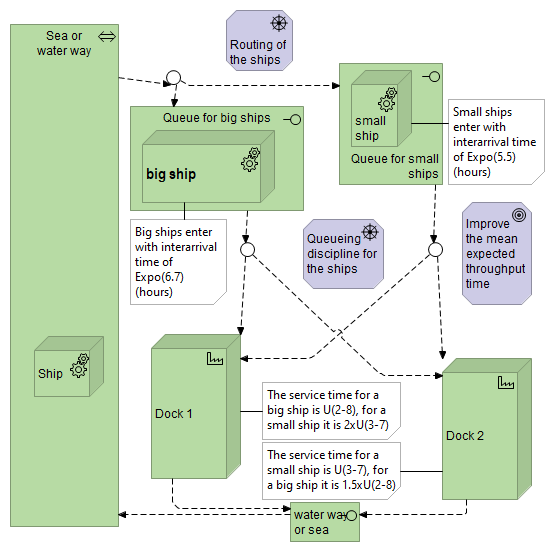

Case 4 - A Harbour

A harbour can host two types of ships; Small and Big ships. Small ships arrive with an interarrival time exponentially distributed with a mean of 5,5 hours. Big ships arrive with an interarrival time exponentially distributed with a mean of 6,7 hours. There are two docks (dock1 and dock2) at this harbour where ships can be unloaded. Small ships are unloaded at dock1 with a service time uniformly distributed between 3 and 7. Big ships are unloaded at dock2 with a service time uniformly distributed between 2 and 8. If dock1 is empty and there are Big ships waiting at dock2 then a Big ship can go to dock1 and is served with 1,5Uniform(2,8). If dock2 is empty and there are Small ships waiting at dock1 then a Small ship can go to dock2 and is served with 2Uniform(3,7). For both docks the queue discipline is SPT (Shortest processing time first). The management team of the harbour wonders if closing dock1 to Big ships and dock2 to Small ships would improve the mean expected throughput time of ships at the harbour. Another question is if it is better to use simply a FIFO rule (First In First Out) instead of the SPT rule? How can we help the management team to get answers to their questions?

This case is situated at the meso level and illustrates the possible scope of a project or iteration. This is a typical case from a simulation course.

- CPIM01 - Identification and Validation at the Harbour

- CPIM02a - Scope and Variables in the Harbour Case

- CPIM02b - Conceptual Model for the Harbour Case

This case has been part of a course on the Simulation of Operational Processes that colleagues and me have been teaching between 2004 and 2008.