Operating Systems

An operating system is software that manages computer hardware and software resources for computer applications. For example Microsoft Windows could be the operating system that will allow the browser application Firefox to run on our desktop computer.

Variations on the Linux operating system are the most popular on our Raspberry Pi. Often they are designed to work in different ways depending on the function of the computer.

Linux is a computer operating system that can be distributed as free and open-source software. The defining component of Linux is the Linux kernel which was first released on 5 October 1991 by Linus Torvalds.

Linux was originally developed as a free operating system for Intel x86-based personal computers. It has since been made available to a wide range of computer hardware platforms and is one of the most popular operating systems on servers, mainframe computers and supercomputers. Linux also runs on embedded systems, which are devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system; this includes mobile phones, tablet computers, network routers, facility automation controls, televisions and video game consoles. Android, the most widely used operating system for tablets and smart-phones, is built on top of the Linux kernel. In our case we will be using a version of Linux that is assembled to run on the ARM CPU architecture used in the Raspberry Pi.

The development of Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. Typically, Linux is packaged in a form known as a Linux ‘distribution’, for both desktop and server use. Popular mainstream Linux distributions include Debian, Ubuntu and the commercial Red Hat Enterprise Linux. Linux distributions include the Linux kernel, supporting utilities and libraries and usually a large amount of application software to carry out the distribution’s intended use.

A distribution intended to run as a server may omit all graphical desktop environments from the standard install, and instead include other software to set up and operate a solution ‘stack’ such as LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP). Because Linux is freely re-distributable, anyone may create a distribution for any intended use.

Welcome to Raspberry Pi OS

The Raspberry Pi OS Linux distribution is based on Debian Linux. This is the official operating system for the Raspberry Pi.

Raspberry Pi OS and Raspbian

Up until the end of May 2020 the official operating system was called ‘Raspbian’ and there will be many references to Raspbian in online and print media. With the advent of an evolution to a 64 bit architecture, the maintainers of the Raspbian code (which is 32 bit) didn’t want to have the confusion of the new 64 bit version being called Raspbian when it didn’t actually contain any of their code. So the Raspberry Pi Foundation took the opportunity to opt for a name change to simplify future operating system releases by changing the name of the official Raspberry Pi operating system to ‘Raspberry Pi OS’. The 32 bit version of Raspberry Pi OS will no doubt continue to draw from the Raspbian project, but the 64 bit version will be all new code.

Operating System Evolution

At the time of writing there have been six different operating system releases published based on the Debian Linux distribution. Those six releases are called ‘Wheezy’, ‘Jessie’, ‘Stretch’, ‘Buster’, ‘Bullseye’ and ‘Bookworm’. Debian is a widely used Linux distribution that allows Raspberry Pi OS users to leverage a huge quantity of community based experience in using and configuring software. The Wheezy edition is the earliest and was the stock edition from the inception of the Raspberry Pi till the end of 2015. From that point there were new distributions releases roughly every two years with the latest ‘Bookworm’ being released at the end of 2023. A great deal of effort goes into maintaining the ability for new Operating Systems to support the older Raspberry Pi boards. This means that you can download and install the most recent 32 bit version and it will still work on a Pi 1. However, older boards which don’t support a 64 bit architecture will not be able to run the newer 64 bit Operating Systems.

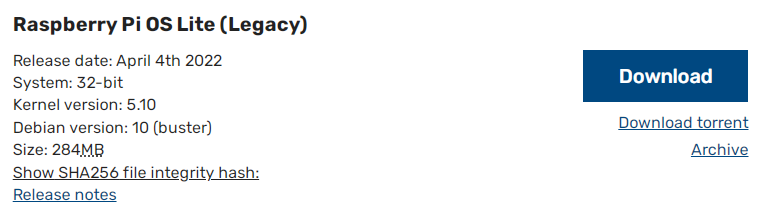

Downloading

The best place to source the latest version of the Raspberry Pi OS is to go to the raspberrypi.com page; https://www.raspberrypi.com/software/operating-systems/. We will download the ‘Lite’ version (which doesn’t use a desktop GUI). If you’ve never used a command line environment, then good news! You’re about to enter the World of ‘real’ computer users :-).

You can download via bit torrent or directly as a zip file, but whatever the method you should eventually be left with an ‘img’ file for Raspberry Pi OS.

To ensure that the projects we work on can be used with versions of the Pi from the B+ onwards we need to make sure that the version of Raspberry Pi OS we use is from 2015-01-13 or later. Earlier downloads will not support the more modern CPU of later models. To support the newer CPU of the B3+ and later (and all the previous CPUs) we will need a version of Raspberry Pi OS from 2018-03-13 or later.

We should always try to download our image files from the authoritative source!

Writing the Operating System image to the SD Card

Once we have an image file we need to get it onto our SD card.

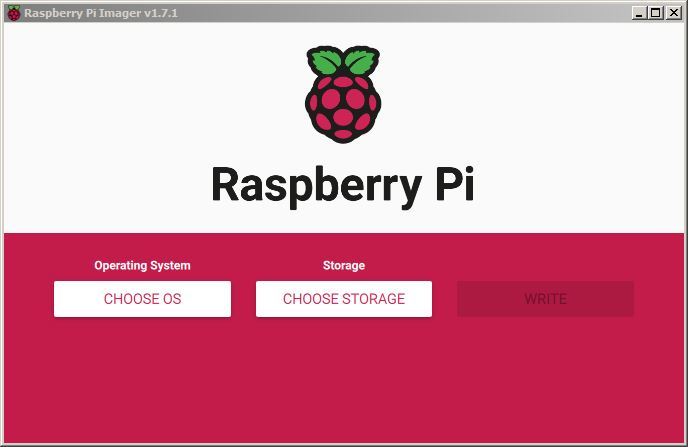

We will work through an example using Windows 7 but the process should be very similar for other operating systems as we will be using the excellent software Raspberry Pi Imager which is available for Windows, Linux and macOS.

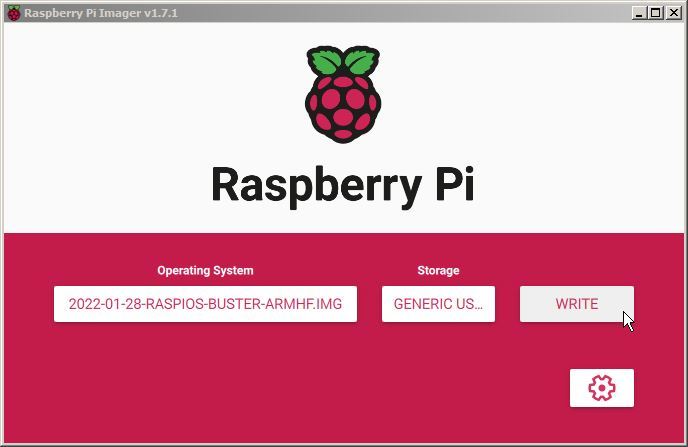

Download and install Raspberry Pi Imager and start it up.

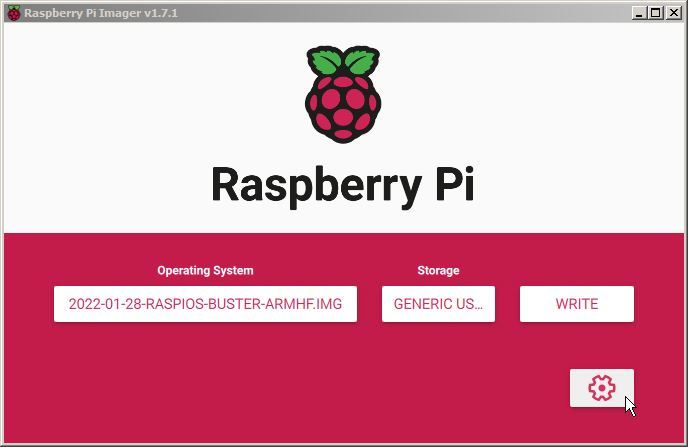

Select the ‘CHOOSE OS’ button.

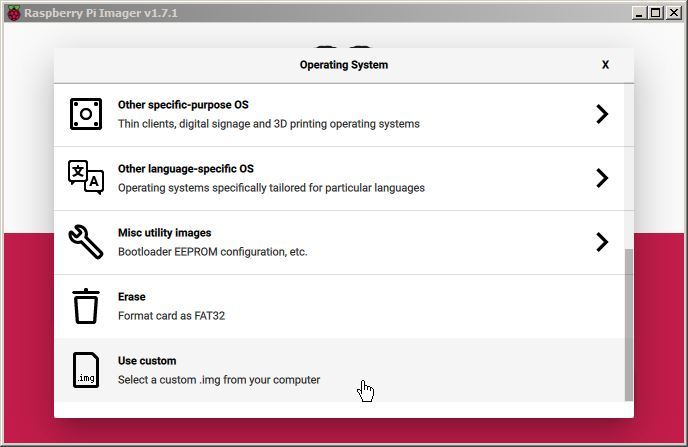

Scroll to the ‘Use custom’ option. This will allow us to have some finer degree of control over which OS we are installing.

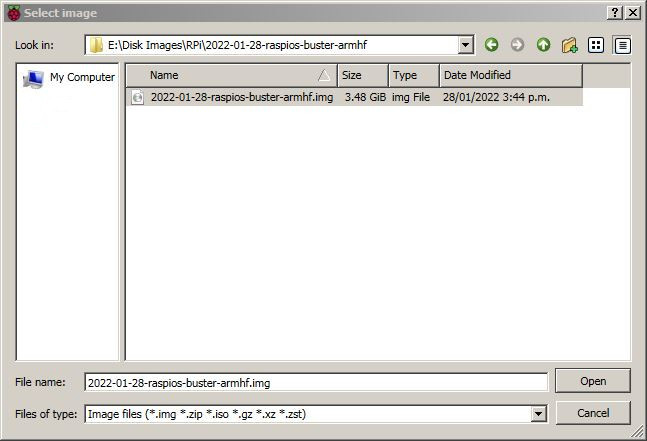

Navigate to the location of the image file that we downloaded earlier. select that and press the ‘Open’ button.

You will need an SD card reader capable of accepting your MicroSD card (you may require an adapter or have a reader built into your desktop or laptop).

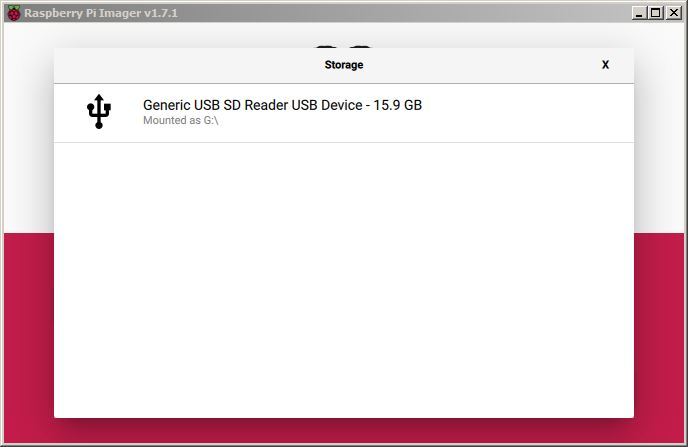

Now select the ‘CHOOSE STORAGE’ button and we will be presented with the SD card that

Assuming that your SD card is in the reader you should see Raspberry Pi Imager automatically select it for writing (Raspberry Pi Imager is very good at presenting options for installing that are only SD cards).

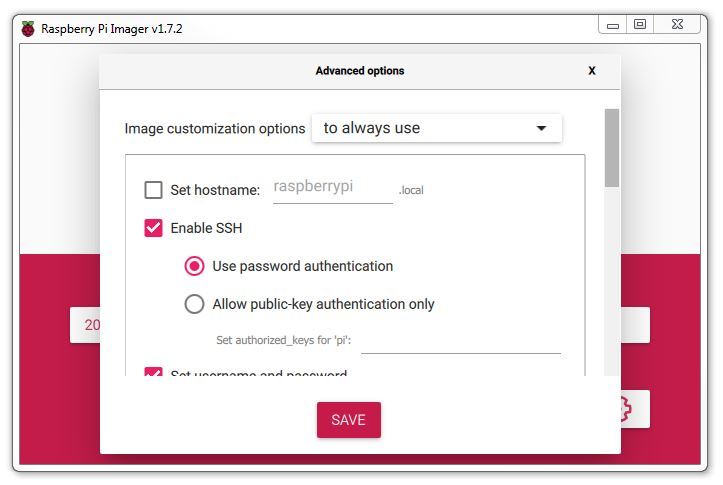

Before we write our SD card we will configure some of it’s initial settings (this is a super useful step that will save us time and effort later).

To do this click on the gear icon.

Presuming that we will want to make these options the same for future use, select the Image customisation options to ‘to always, use’

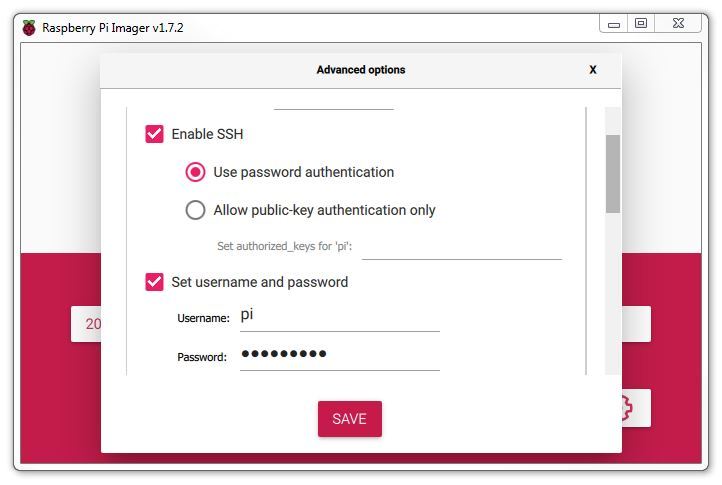

We will enable SSH so that we can remotely access the Pi and set a suitable password. Here I am setting it to the default username ‘Pi’ with the default password ‘raspberry’. You should definitely use your own username and password.

One of the awesome things when learning to use a Raspberry Pi comes when you begin to access it remotely from another computer. This is a bit of an ‘Ah Ha!’ moment for some people as they begin to appreciate just how networks and the Internet is built. We are going to enable and use remote access via what is called ‘SSH’ (this is shorthand for Secure SHell). We’ll start using it later in the book, but for now we can take the opportunity to enable it for later use.

SSH used to be enabled by default, but doing so presents a potential security concern, so it has been disabled by default as of the end of 2016. In our case it’s a feature that we want to use.

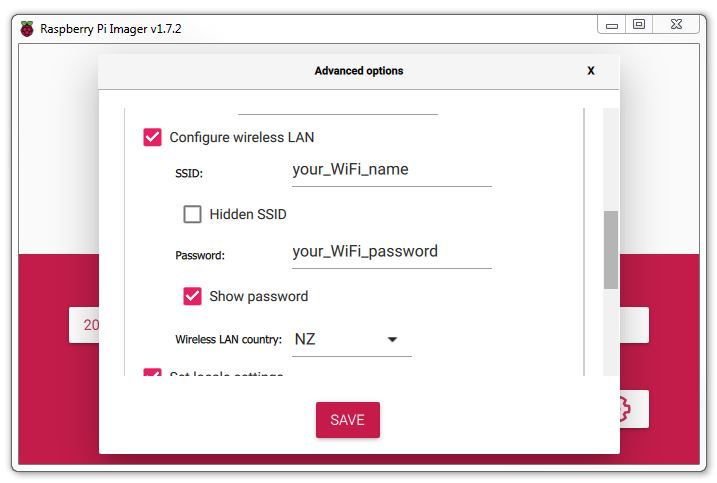

If your Pi has WiFi, you can select to configure the wireless LAN and enter it’s password. Likewise you will want to select the Wireless LAN Country for the country that you are in.

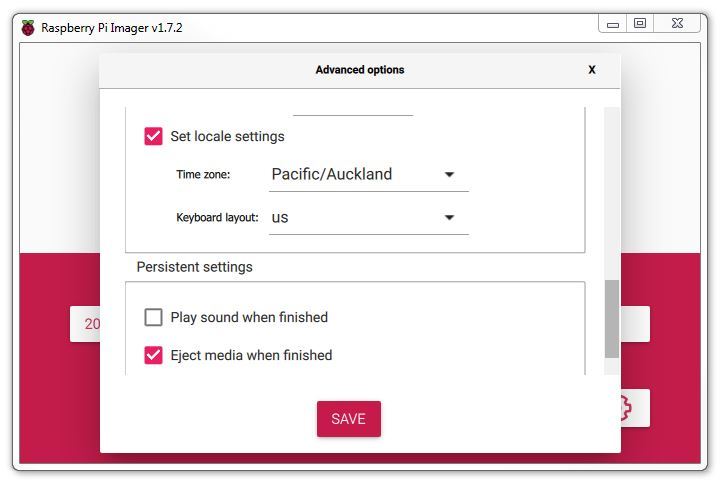

Lastly we should set our locale setting to our location and depending on your keyboard type, select the appropriate one.

Once we are happy with our settings. click on ‘SAVE’.

With everything ready. Click on the ‘WRITE’ button

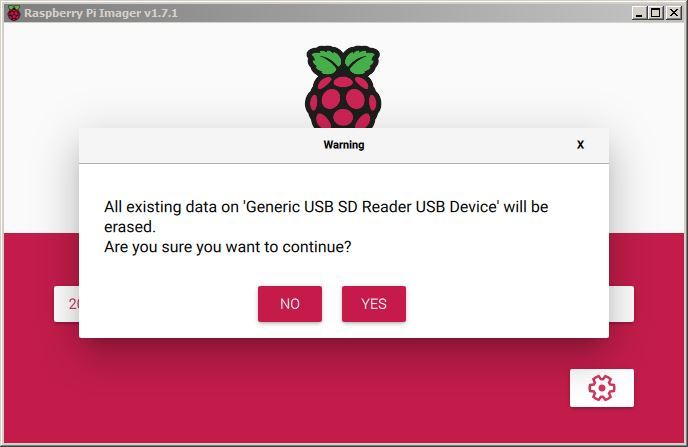

A friendly warning will let us know that if we proceed, the SD card will be erased. Press ‘YES’ if you are sure that you want to continue.

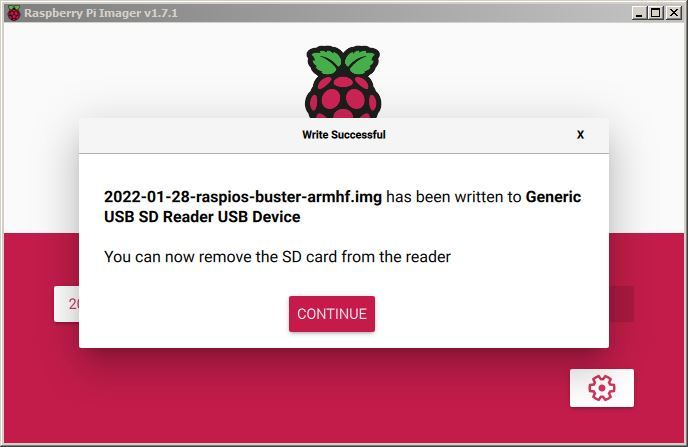

The writing process will start and progress. The time taken can vary a little, but it should only take about 3-4 minutes with a class 10 SD card.

Once done, we should be told that the process has completed successfully and that we can remove our SD card.

Powering On

Insert the card into the slot on the Raspberry Pi and turn on the power.

You will see a range of information scrolling up the screen before eventually being presented with a login prompt.

The Command Line interface

Because we have installed the ‘Lite’ version of Raspberry Pi OS, when we first boot up, the process should automatically re-size the root file system to make full use of the space available on your SD card. If this isn’t the case, the facility to do it can be accessed from the Raspberry Pi configuration tool (raspi-config) that we will look at in a moment.

Once the reboot is complete (if it occurs) you will be presented with the console prompt to log on;

The default username and password (that we set earlier, buy yours may be different) is:

Username: pi

Password: raspberry

Enter the username and password.

Congratulations, you have a working Raspberry Pi and are ready to start getting into the thick of things!

If you didn’t take the opportunity to set some of the advanced options as above with the Raspberry Pi Imager, you might want to do some house keeping per below.

Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool

The steps in this section will only be required if you did not set them with the Raspberry Pi Imager.

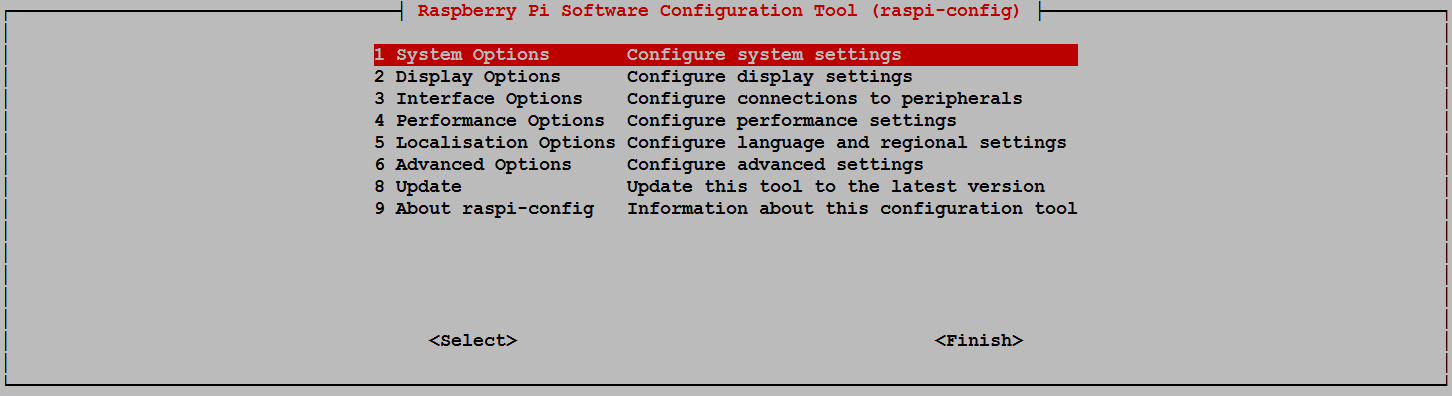

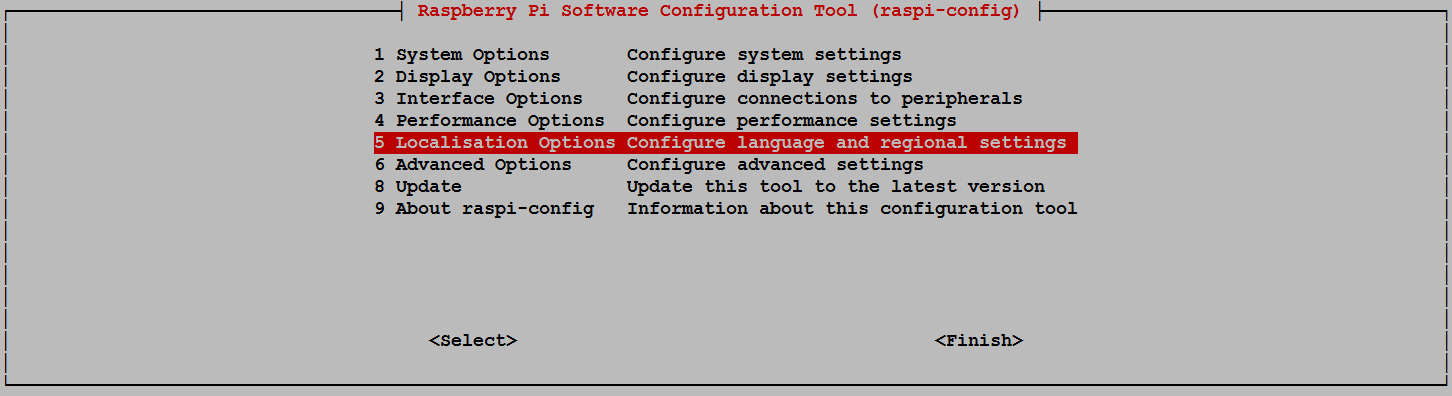

We will use the Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool to change the locale and keyboard configuration to suit us. This can be done by running the following command;

Use the up and down arrow keys to move the highlighted section to the selection you want to make then press tab to highlight the <Select> option (or <Finish> if you’ve finished).

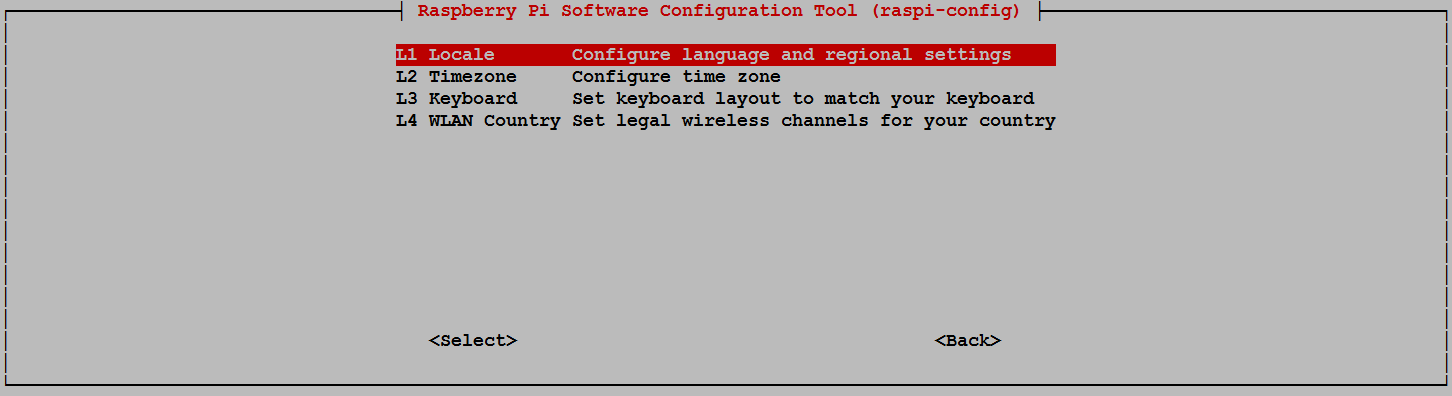

Lets change the settings for our operating system to reflect our location for the purposes of having the correct time, language and WiFi regulations. These can all be located via selection ‘5 Localisation Options’ on the main menu.

Select this and work through any changes that are required for your installation based on geography.

Once you exit out of the raspi-config menu system, if you have made a few changes, there is a possibility that you will be asked if you want to re-boot the Pi. That’s just fine. Even if you aren’t asked, it might be useful since some locales can introduce different characters on the screen.

Once the reboot is complete you will be presented with the console prompt to log on again;

Software Updates

After configuring our Pi we’ll want to make sure that we have the latest software for our system. This is a useful thing to do as it allows any additional improvements to the software we will be using to be enhanced or security of the operating system to be improved. This is probably a good time to mention that we will need to have an Internet connection available.

Type in the following line which will find the latest lists of available software;

You should see a list of text scroll up while the Pi is downloading the latest information.

Use sudo apt-key list and find the entry that is in /etc/apt/trusted.gpg.

Then we convert this entry to a .gpg file, using the last 8 numeric characters from above (90FDDD2E). The characters that you have will most likely be different!

sudo apt-key export 90FDDD2E | sudo gpg –dearmour -o /etc/apt/trusted.gpg.d/raspbian.gpg

If we have more than one warning message we can repeat the above commands for each generated by sudo apt update.

Then we want to upgrade our software to latest versions from those lists using;

The Pi should tell you the lists of packages that it has identified as suitable for an upgrade along with the amount of data that will be downloaded and the space that will be used on the system. It will then ask you to confirm that you want to go ahead. Tell it ‘Y’ and we will see another list of details as it heads off downloading software and installing it.