8 Using the Grid Method with Natural Materials

Origins

While writing Chapter 26 - Rock Glazes in “Stoneware Glazes - A Systematic Approach” it became obvious that it would be very useful to have an experimental technique enabling systematic variation of alumina and silica where the Seger formula of a rock was not known. The biaxial blends presented on Page 205 (Page 344 in the First Edition) do this. The recipe method presented in this book actually arose from this exercise. So in applying it to natural materials, we are really going back to the source.

While writing Chapter 26 - Rock Glazes in “Stoneware Glazes - A Systematic Approach” it became obvious that it would be very useful to have an experimental technique enabling systematic variation of alumina and silica where the Seger formula of a rock was not known. The biaxial blends presented on Page 205 (Page 344 in the First Edition) do this. The recipe method presented in this book actually arose from this exercise. So in applying it to natural materials, we are really going back to the source.

One of the big advantages of using recipe rather than Seger formula is that we can use any flux material we like without needing an analysis. Seger formula is great if we are chasing a concept - trying to reproduce a particular type of celadon glaze for example. It may be critical to have (or to exclude) certain oxides, and accurate analyses will enable us to do this, and to accurately measure the amounts. But using the Seger method we will not be able to introduce materials where we have no analysis figures.

Using the recipe grid method as presented here allows us to take any natural material that we know is a flux material and use it in a grid and systematically vary alumina and silica over a large range. This vitally important experiment works even without any idea what the flux material contains.

Although we do not need to know the analysis of a raw material it’s useful to be able to classify it into one of the categories:

flux material

alumina source

silica source (e.g. grass ash)

colourant or opacifier

These will be considered one at a time.

Flux Material

Wood Ashes

Virtually any wood ash can be used as a flux material. They are very variable in composition, but many are high in CaO (lime) and a simple way of introducing wood ash into a glaze is to replace whiting (the most common source of CaO in glazes) with wood ash on a weight for weight basis. (The glaze will almost certainly be different.) If the wood ash is not washed, it will usually contain some soluble flux materials that might make for difficulties in glaze application. They can be very caustic. Use rubber gloves.

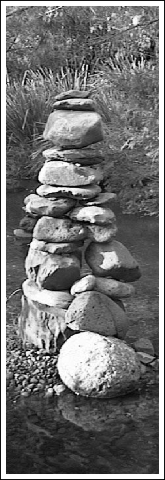

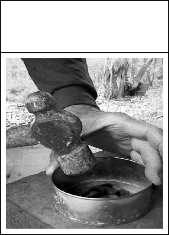

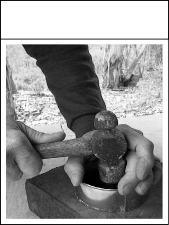

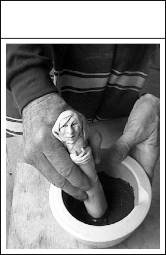

Rock and Mineral Materials

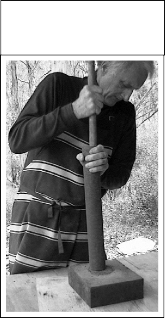

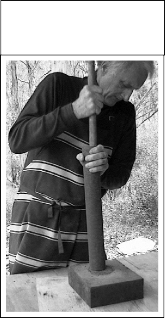

It is very easy to test rocks and minerals to see if they will melt in the firing. Enough to glaze a miniature bowl e.g. 2 inches (50mm) across takes only a few minutes to prepare. Almost any rock can be easily crushed with a hammer or a “dolly” to fine gravel, and then ground with some water in a mortar and pestle until most will pass through a fine (say, 100 mesh) sieve.

Igneous Rocks

Serpentinite

Pyroxenite

Dunite

Basalt

Dolerite (Diabase)

Gabbro

Andesite

Micro-diorite

Diorite

Trachyte

Micro-syenite

Syenite

Rhyolite

Pumice

Quartz-felsite

Granite

Looking at this list of rocks, the amount of silica incorporated into the rock increases (and therefore the fluxing power decreases) as we move down the list. In general, the rocks at the top of the list (ultrabasic and basic rocks) have a higher flux and iron oxide content and give darker glazes than those at the bottom of the list (acidic rocks, especially granite).

Sedimentary and Metamorphic Rocks

Some of these make excellent flux materials, but many are very high in silica and alumina. It’s difficult to make generalizations about them. Get a geologist friend to help, or just try them and see. If a fusion test melts the rock, it can be used as a flux material. In most cases we are talking about stoneware materials, but many can be used in mid-fire, or in small amounts in earthenware.

Metamorphic rocks form when an existing rock is changed by pressure and/or heat. They will often be similar in composition to the rocks from which they derive. So for example a gneiss might be chemically similar to the original granite. If the rock has been significantly heated, the composition might be changed a lot.

Many sedimentary rocks are high in silica but some will reflect the composition of nearby igneous rocks from which they are derived and be useful as a flux material.

Arcose sandstone is high in feldspar (usually potash).

See the end of this chapter for a list of useful references.

Alumina Sources

This refers to a material that we are adding to the glaze mainly to provide extra alumina (as opposed to adding for the purpose of providing a flux or extra silica). Any of these materials can be used in place of kaolin (as the source of variable Al2O3) on the vertical axis of a (non-standard) grid. However the Recipe Grid and Recipe Table are designed for kaolin, and using these recipes and substituting other alumina sources will give differing degrees of usefulness. You should find for example that replacing kaolin with alumina gram for gram will give many unfused glazes across the top of the grid. This is where the Seger approach comes into its own but here we are keeping the method as simple as possible by sticking with recipes.

Clays

The most usual alumina sources are clays, kaolin (china clay) and ball clay being the most common. Ball clay has a lot more silica and less alumina than kaolin, and it usually contains a small amount of flux materials and noticeable iron content too.

Alumina etc.

Pure alumina or alumina hydrate are sometimes added to a glaze as a source of Al2O3, especially where we are attempting to simultaneously achieve high Al2O3 and low SiO2 values. The big advantage of using a clay rather than pure alumina as our source of Al2O3 is that clay is also a suspender, and it helps make the glaze less powdery before it is fired. Bauxite is common is some places in Australia. It is essentially Al2O3.2H2O - usually there is a little of the colourant iron oxide as well.

Silica Sources

Quartz, Silica, Flint

General Formula: SiO2 There are many different sources of reasonable pure SiO2, all of which can be used as the source of variable SiO2 in the grid sets. The materials that come to your pottery supplier in bags may be called, “silica”, “flint”, “quartz”, “potters flint”, and they all are much the same and give fairly similar results. If your “flint” is really from ground up flint stones, the glazes will probably craze less.

Opal

Has the general formula: SiO2.nH2O

The “n” in front of the water molecule indicates variable amount. There are many forms of non-precious opal widely available. One of the most useful is:

Diatomite (diatomaceous earth)

This is formed from the silica rich shells of diatoms and other tiny lifeforms. The water content causes it to shrink a lot as it dries, much like a clay, and just like a clay it will cause crawling if used in large amounts. Any kind of crawling can be used to achieve lizard-skin effects (photo). They usually look best with another glaze underneath bleeding through at the cracks. The underneath glaze does not have to be too thick, and it can have a lower melting point than the top glaze containing the diatomite.

Using Natural Materials in a Standard Recipe Grid.

We can include any natural flux material in Glaze C, our starting point, and make a normal grid. We can even make Glaze C entirely from natural materials as the starting point.

Some suggestions for Glaze C:

- Take any Glaze C recipe containing whiting, and replace this with wood ash.

- 100% Wood ash Also, reduce the wood ash by introducing other flux materials such as dolomite, talc etc.

- 100% Rock powder Also, reduce the rock powder by introducing other flux materials such as whiting, dolomite, talc etc.

- 50% Wood ash 50% Igneous rock (e.g. basalt)

Vary the proportions from 50/50 (e.g. to 75/25)