Introduction

Firstly we need to cover a few basics for those who’ve not met up with glazes before…. briefly:

What is a Glaze?

Glaze is a special glass.

A base glaze is the glaze before we add any colourants or opacifiers. It consists of three main ingredients:

- A glass former (this is essential), usually silica.

- Some fluxes (essential) to melt the silica at a reasonable temperature. Normally we use more than one flux.

- Alumina (nearly always) so the glaze is not too runny.

To the base glaze we can add colourants or opacifiers and other additives(optional).

We will learn the chemical formulae for the twelve oxides used in the base glaze as it only takes a minute, and it makes accessible a lot of useful information.

Ian Currie’s Blue-in-the-Face Chemistry Course.

The deal is I hold my breath until the student understands all the chemistry he or she needs for this method. I’ve not passed out yet. Starting now:

We need to be able to recognize the formulae of these 12 oxides.

| \(\textbf{R}_{\textbf{2}}\textbf{O}\)-type fluxes: |

| 1. \(Li_{2}O\) is Lithium oxide |

| 2. \(Na_{2}O\) is Sodium oxide |

| 3. \(K_{2}O\) is Potassium oxide |

| \(\textbf{RO}\)-type fluxes: |

| 4. \(CaO\) is Calcium oxide |

| 5. \(MgO\) is Magnesium oxide |

| 6. \(ZnO\) is Zinc oxide |

| 7. \(SrO\) is Strontium oxide |

| 8. \(BaO\) is Barium oxide |

| 9. \(PbO\) is Lead oxide |

| This one is both a flux and a glass former: |

| 10. \(B_{2}O_{3}\) is boric oxide |

| Stiffener: |

| 11. \(Al_{2}O_{3}\) is Alumina |

| Glass former: |

| 12. \(SiO_{2}\) is Silica |

| It’s also useful to know that: |

| \(H_{2}O\) is water |

| \(CO_{3}\) is carbonate |

These last two are sometimes found in the raw materials, but disappear during the firing. [Take a breath, Ian!]

There are more, but in this method we only need to know the formulae of these 12 oxides that go to make up the base glaze.

Raw Materials

Glaze theory would be easy if we made our glazes of just these twelve oxides, but when we come to mix the ingredients together in the bucket, for practical reasons only a few are used in the pure oxide form. (Some are soluble, some react with water etc.) Many raw materials are compounds of several oxides, some are carbonates, some hydrates (containing \(H_{2}O\)).

| Oxide | Some Common Sources* |

|---|---|

| Flux Materials: | |

| \(Li_{2}O\) | 1. Lithium carbonate, Petalite, Spodumene |

| \(Na_{2}O\) | 2. Soda feldspar, Nepheline syenite, Frit |

| \(K_{2}O\) | 3. Potash feldspar, Frit |

| \(CaO\) | 4. Whiting, Limestone, Wollastonite, Wood ash |

| \(MgO\) | 5. Magnesium carbonate, Dolomite, Talc |

| \(ZnO\) | 6. Zinc Oxide |

| \(SrO\) | 7. Strontium carbonate |

| \(BaO\) | 8. Barium carbonate |

| \(PbO\) | 9. Frit |

| \(B_{2}O_{3}\) | 10. Frit, Colemanite, Gerstley borate |

| Sources of Alumina and Silica: | |

| \(Al_{2}O_{3}\) | Clay, Kaolin, Alumina |

| \(SiO_{2}\) | Silica, Quartz, Flint |

Once again, there are many more sources than those listed here. But just for now, we are trying to get a feeling for how it all hangs together.

An Approach to Studying Glazes

Origins

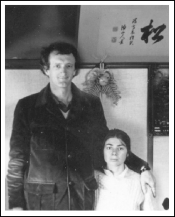

My wife Christine and I spent over a year in Japan in 1971 and 72. I went there on a travelling art scholarship to study Japanese Ceramics, and one of the things I focused on was the Japanese approach to studying glazes. It was interesting because they had applied western methods of glaze technology to their traditional glazes, and I found this fusion of the western scientific approach and traditional empirical methods. I learned from a variety of sources. We traveled around Japan to the various ceramic production centres visiting potteries and potters, and also visiting the local ceramic research centres. I also had a series of private tutorials with a leading glaze technologist, Mr. Masataro Ōnishi.

This was about thirty years ago, and in the west ceramic artists didn’t know anywhere near as much as we do now. It was common for potters to be completely secretive about their glazes, and to find this stuff being freely taught and in their textbooks made me feel I had come to the source!

Anyway, Mr. Ōnishi and I would sit on opposite sides of a coffee table, and he would scribble out notes while explaining. My command of the language was fairly basic at this early stage in the tour, but we both understood Seger formula, which is a universal language. At that time, many potters were of the opinion that for a glaze all you needed was the glaze recipe. He presented me with this 7 point approach to glaze research:

The 7 Point Approach:

1. \(R_{2}O.RO\) (Fluxes)

2. Alumina/Silica ratio

3. Amount of Silica

4. Colourants and/or opacifiers

5. Clay Body

6. Special requirements of any materials, e.g. special source, fine, coarse etc.

7. Special firing requirements

He introduced me to the concept of a standard limestone glaze. He would write the Seger formula for this standard:

| \(0.3 K_{2}O\) | ||

| \(0.5 Al_{2}O_{3}\) | \(4.0 SiO_{2}\) | |

| \(0.7 CaO\) |

and locate it on an alumina/silica diagram as a kind of datum point in the middle of this glaze landscape, a peg in the ground so you knew where you were and from which you could look around. He would relate all glazes back to this one standard. This glaze is almost identical to the glaze right in the middle of the 0.7 Limestone Set, a set of 35 glazes which we will use as our own datum. I.C.

Some Standards

1. Standard Cone 9~10 Limestone Glaze

| A recipe for Ōnishi’s glaze is: |

| 42% K Feldspar |

| 27% Silica |

| 18% Whiting |

| 13% Kaolin |

2. Bernard Leach Glaze Looking at the recipe in 1. we find it is close to another standard glaze:

| Bernard Leach’s Cone 8 Limestone Glaze |

| 40% Feldspar |

| 30% Silica |

| 20% Whiting |

| 10% Kaolin |

(Published in his classic “A Potter’s Book” in 1940, an early 4:3:2:1 glaze.)

3. Standard pyrometric cones

In the midfire to porcelain range and higher the flux composition of standard pyrometric cones is the same as that in Ōnishi’s standard glaze. If we severely overfire the actual cones they produce a clear shiny limestone glaze. Ōnishi’s Standard Cone 9~10 Limestone Glaze has roughly the same chemical composition as cone number 4.

Extending the Range

There is a reason why glazes like this have been adopted as a standard. They are typical, reliable, middle-of-the-road glazes with a good firing range and few problems. Varying the 4 glaze ingredients produces a very wide range of possible glazes from high feldspar, to high calcium to high alumina to high silica glazes. And this glaze is more or less right in the middle of the possible range for Cone 9 to 10.

Later we will consider an exercise to produce the 0.7 Limestone Set. In this exercise we keep the \(\textbf{K}_{\textbf{2}}\textbf{O}\) and \(\textbf{CaO}\) constant in the proportions given in the Standard Cone 10 Limestone Glaze, and vary alumina and silica over a wide range above and below the figures shown above in the Seger formula. Mr. Ōnishi’s glaze sits almost exactly in the middle of this set. Similar sets are presented for midfire and earthenware firing ranges.

The high lime content of the 0.7 Limestone Set gives us a good stable base to start from. We can then explore the introduction of other fluxes by replacing some of the lime with magnesia (\(MgO\)), zinc oxide (\(ZnO\)), baria (\(BaO\)), Strontia (\(SrO\)) etc. Also the original balance of lime from the whiting and potash from the feldspar will be altered.

The set is named “The 0.7 Limestone Set” because in the Seger formula all 35 glazes contain 0.7 molecular parts of \(CaO\). The midfire and earthenware equivalent sets are similarly high in lime (\(CaO\)) but manage to lower the firing range mainly by addition of \(B_{2}O_{3}\) (in frit), and substitution of soda (\(Na_{2}O\)) for potash (\(K_{2}O\)).

The “grid method” facilitates the full 7 point approach of Mr. Ōnishi. The main focus presented in this book however will be to detail the use of the grid technique; no attempt has been made to provide once again the sort of basic ceramic information that is now so widely available.

A> I have a couple of friends who live in Parkerville in Western Australia. Tim is a geologist and Georgina a potter. There is a geological contribution from Tim in Chapter 8. Our Lives have been spliced together strangely by fate.

A>

A> Just after the War (WW2) when I was about 5 years old my parents and I went to liver at Parkerville. It was probably wher eI was happiest as a boy… our family was back together after the war and Parkerville is a very beautiful place. Eucalyptus open forrest bushland for the most part, then with very few houses, and a beautiful creek called Jane Brook bubbling through the middle. We had a small mixed farm there. Dad ran the only local milk run, and also sold eggs, and seasonally some fruit and vegetables. I dont know enough about this period of my parents’ lives. It seemed very happy but obviously didn’t work out. We were only there a couple of years and then we moved on.

A>

A> In the brief period I was there I connected with Parkerville as children do when they live in such a beautiful place. I had an aunt living nearby in a cottage along Falls Road. Her name is Betsy and she is 96 years old and has always been an artist. (She had her first solo show in 1999.) She lived there with an artist named James Linton in a small cottage he built. It was one of the special plaes in Parkerville. As well as having a currant-grape vine that we could raid, the house was full of wonderful objects. My aunt stil lhas in her flat the 4 feet tall plaster Venus de Milo that stood just inside the doorway. When I asked what happened to her arms, Betsy said she was run over by a train. Not many people know this. The house contained many oriental artifacts.

A>

A> Linton made serveral trips to China in the early twentieth century and had ceramics, chests, furnature, etc and one room of his studio had the smell of turps and oil paints. There were also carved objects made by Linton himself, and also Betsey’s brother Kitchener Currie (Photo in Appendix 3.)

A>

A> I first returned to Parkerville in 1980, and was surprised and delighted at that time ti find how little it had changes. And one of my main visits had to be Betsey Linton’s old house, which I visited twice on that trip. I always find it difficult to intrude and there were people there both times. However on the second visit I decided I wasn’t a shy 6 yea old any more, and plucked up my courage, went back and introduced myself as Ian Currie who had lived in the area 33 years ago and whose aunt used to live here and would they mind if I looked around. There was a man and a woman and a couple of kids.

A>

A> They said they didn’t own the house, were just looking with a view to buying, and who was my aunt? I told them and the woman exclaimed that Betsey Linton was a very good friend. They knew that she had lived in this house and they had heard it was for sale.

A>

A> I had a good look around the garden and through the house absorbing as moch as I could, then having come 33 years through time and thousands of miles through space to place my imprimatur upon the deal I stepped back into my Tardis and space/time-transported out of there. Tim and Georgina, for it was they, bought the cottage! I’ve been back numerous times since, and they have become dear friends. Seeing how the place affected me, they offered me “land rights” - the right to come and go in their home as I please - in the house where my Aunt Betsey and James Linton used to live! Now that is a gift!