3 Choosing a Starting Point

The starting point in each set is Glaze C (Glaze No. 31) which is composed of one or more “flux materials” (see List of Flux Materials in this chapter). The purpose of this chapter is to outline some methods for choosing the flux materials for a set. A beginner would be excused for not knowing where to start.

Those new to this approach would be well advised to start with a standard set, perhaps one of the example sets below. It soon becomes apparent however that there are large uncharted oceans awaiting the adventurous explorer. This chapter outlines a way of navigating the unknown and discovering treasure, while gaining deep insight into glaze principles.

Several approaches are given in this chapter:

- Example Sets

We can use some of these suggestions as a starting point. Once a few grid sets have been prepared, the student will inevitably develop a sense of how to choose a set of flux materials for Glaze C. - “Rules of Thumb”

Refer to rules of thumb given in this chapter. - Family Set

We may just choose a known recipe that does something interesting and decide to base a set around the fluxes it uses. This produces the family of glazes with the same set of fluxes as the original recipe (and the same set of colourants/opacifiers, if these are used) but with varying alumina and silica. - Random Selection

If we know nothing, we may even choose a set of flux materials at random! This is not as daft as it sounds.

For this chapter we will focus on gaining some of the theoretical knowledge necessary for making a rational choice of fluxes. It is then up to us individually whether or not we wish to be rational, or go for option 4 above. :) Seriously!

1. Example Sets

Glaze C Recipes

Most of the examples given here are base glaze sets, but we can add a small amount of colouring oxide to all the glazes if we wish. The small amount ensures that the colourant should not significantly alter the glaze characteristics like surface, opacity, crystal formation, maturity, opalescence etc. In other words the glazes should be very similar to the base glazes alone, but with colour. There will be some differences however. For example, there might appear some colour break in some of the glazes. This is where the glaze breaks from one colour to another as thickness varies. Usually we find that the effect is there very subtly in the base glaze set, but the colourant brings it out. Sometimes the colourant, especially iron oxide, will substantially increase the intensity and distribution of opalescence or milkiness in the high silica glazes.

The barium glazes should not be used inside utilitarian ware unless tested safe for barium release.

Although these are all “recipes” we must remember that they are the starting point recipes for the whole set of 35 glazes. It is not intended that students make just these recipes; they are over-rich in fluxes and in many cases will not melt at the suggested temperature range. When we make up a whole set based on one of these starting points however, we should find plenty of melted glazes.

Example Sets - Glaze C

Set 1 - 0.7 Limestone Set - (S)

70 Potash Feldspar

30 Whiting

Set 2 - Feldspar Set - (S)

90 Potash Feldspar

10 Whiting

Set 3 - High Lime Set - (S)

30 Potash Feldspar

70 Whiting

Set 4 - Magnesia Set - (S)

60 Potash Feldspar

17 Whiting

23 Heavy Magnesium Carbonate

Set 5 - Zinc Set (Oxidation only) - (M,S)

60 Potash Feldspar

17 Whiting

23 Zinc Oxide

Set 6 - Barium Set - (M,S)

45 Potash Feldspar

15 Whiting

40 Barium Carbonate

Set 7 - Low Temperature Set (Oxidation only) - (E,M)

60 Ferro Frit 4108 (also 4508 or 3134)

20 Nepheline Syenite

20 Zinc Oxide

Set 8 - Nickel Pinks and Blues (Oxidation only) - (M,S)

40 Potash Feldspar

40 Barium Carbonate

20 Zinc Oxide

(Try adding 2% nickel oxide)

Set 9 - Talc Set - (M,S)

30 Ferro Frit 4108 (also 4508 or 3134)

30 Nepheline Syenite

20 Whiting

20 Talc

(Try adding 0.5% cobalt carbonate.)

Set 10 - Alkaline Set (Includes some matt alkaline glazes) - (M,S)

50 Barium Carbonate

30 Ferro Frit 4110 (or 3110)

20 Whiting

(Try adding some colourant.)

Set 11 - Earthenware Alkaline Set - (E,M)

100 Ferro Frit 4110 (or 3110)

Alternatively, use any low temperature frit.

(Try adding some colourant, e.g. 2% copper carbonate for turquoise.)

Set 12 - Low Temperature Set - (E,M)

50 Gerstley Borate, or High \(B_{2}O_{3}\) Frit

50 Spodumene

Set 13 - Copper Red Set = (M, S)

55 Soda Feldspar

30 Ferro Frit 3134

15 Whiting

+1% copper oxide

+1% Tin Oxide

Set 14 - Magnesia Matt Sett - (S)

40 Potash Feldspar

26 Whiting

20 Talc

10 Dolomite

4 Lithium Carbonate [+ 3% Tin Oxide]

2. Rules of Thumb for Choosing a Flux Set

Broad Principles

- Among the flux materials, we usually choose at least one that contains alumina and silica in addition to the flux component. In the List of Flux Materials these materials are marked with an asterisk *. These are materials like feldspars, frits, and many wood ashes, powdered rock materials etc. We can sometimes use these materials up to 100% in Glaze C, but we usually add other flux materials as well.

- Unless we have very specific objectives, we can put together almost any mix of fluxes in almost any proportions and expect to find glazes that are useful or excellent under some conditions of firing and clay body. In this method there is no “correct” temperature or firing cycle or clay body for a given set. In a particular firing, there will always be some glazes in a set that will be useless (e.g. over- or under-fired) but the systematic variation of kaolin and silica determines that useful (and regularly excellent!) glazes will appear at just the right combination of kaolin and silica. Usually we don’t know just what this combination will be until we do the experiment. Any set can usually be usefully fired over a range of 200 deg. C (360 deg. F) or more.

- To get most of the 35 glazes to melt at mid-fire (1200 deg. C or about 2200 deg. F), we can put up to 35% of frit into Glaze C.

To get most to melt at earthenware (1100 deg C. or about 2000 deg F) we can put 50%, or even up to 100%, of frit into Glaze C. (It is possible to achieve low temperature glazes with just the right mix of “stoneware” fluxes, alumina and silica, but most of the 35 glazes in the set will be unfused.)

Table - List of Flux Materials

| Material | Formula | Max C% |

|---|---|---|

| Barium carbonate | \(BaCO_{3}\) | 50 |

| Barium sulphate | \(BaSO_{4}\) | 50 |

| Bone Ash (arguably not a flux) | \(Ca_{3}(PO_{4})_{2}\) | 50 |

| Calcite | \(CaCO_{3}\) | 60 |

| Chalk | \(CaCO_{3}\) | 60 |

| Colemanite | \(2CaO.3B_{2}O_{3}.5H_{2}O\) (variable) | 50 |

| Cornish stone * | variable | 80 |

| Dolomite | \(CaCO_{3}.MgCO_{3}\) | 40 |

| Feldspar (Potash) * | \(K_{2}O.Al_{2}O_{3}.6SiO_{2}\) | 100 |

| Feldspar (Soda) * | \(Na_{2}O.Al_{2}O_{3}.6SiO_{2}\) | 100 |

| Frits * | various | 100 |

| Gerstley Borate | Similar to Colemanite with some Na | 50 |

| Lepidolite * | \(Li_{2}F_{2}.Al_{2}O_{3}.3SiO_{2}\) (variable) | 40 |

| Limestone | \(CaCO_{3}\) | 60 |

| Lithium carbonate | \(Li_{2}CO_{3}\) | 10 |

| Magnesium carbonate | \(MgCO_{3}\) | 25 |

| Magnesium carbonate (light) | \(3MgCO_{3}.Mg(OH)_{2}.3H_{2}O\) | 25 |

| Manganese carbonate | \(MnCO_{3}\) | 100 |

| Manganese dioxide | \(MnO_{2}\) | 100 |

| Nepheline syenite * | \((K)NaO.Al_{2}O_{3}.4SiO_{2}\) (variable) | 100 |

| Petalite * | \(Li_{2}O.Al_{2}O_{3}.8SiO_{2}\) | 50 |

| Potassium carbonate (Pearl Ash) ~ | \(K_{2}CO_{3}\) | 25 |

| Rock powder - Many rocks make excellent | 100 | |

| flux materials, e.g. basalt, granite. * | ||

| Sodium carbonate (Soda Ash) ~ | \(Na_{2}CO_{3}\) | 40 |

| Spodumene * | \(Li_{2}O.Al_{2}O_{3}.4SiO_{2}\) | 70 |

| Strontium carbonate | \(SrCO_{3}\) | 50 |

| Talc | \(3MgO.4SiO_{2}.H_{2}O\) | 30 |

| Whiting | \(CaCO_{3}\) | 60 |

| Wollastonite | {$$}CaO.SiO_{2}{/$ | 40 |

| Wood Ash (May contain solubles~) * | Variable, (often high in lime) | 100 |

| Zinc oxide | \(ZnO\) | 25 |

- The last column on the right in the List of Flux Materials (previous page) shows the recommended maximum percentage of the material to be used in Corner C. (Note that a material used as 100% of Corner C will vary downwards across the set to a minimum of 35% at Corner B. We must think of the whole set, not just the glaze at Corner C.) These guidelines are necessarily approximate because the maximum amount possible in a glaze is determined by many factors including what other oxides are present.

To choose a set of fluxes to achieve a specific purpose requires some knowledge. This approach enables the beginner to achieve a lot with little or no prior experience, and in so doing actually begin to acquire that knowledge.

Advanced Principles

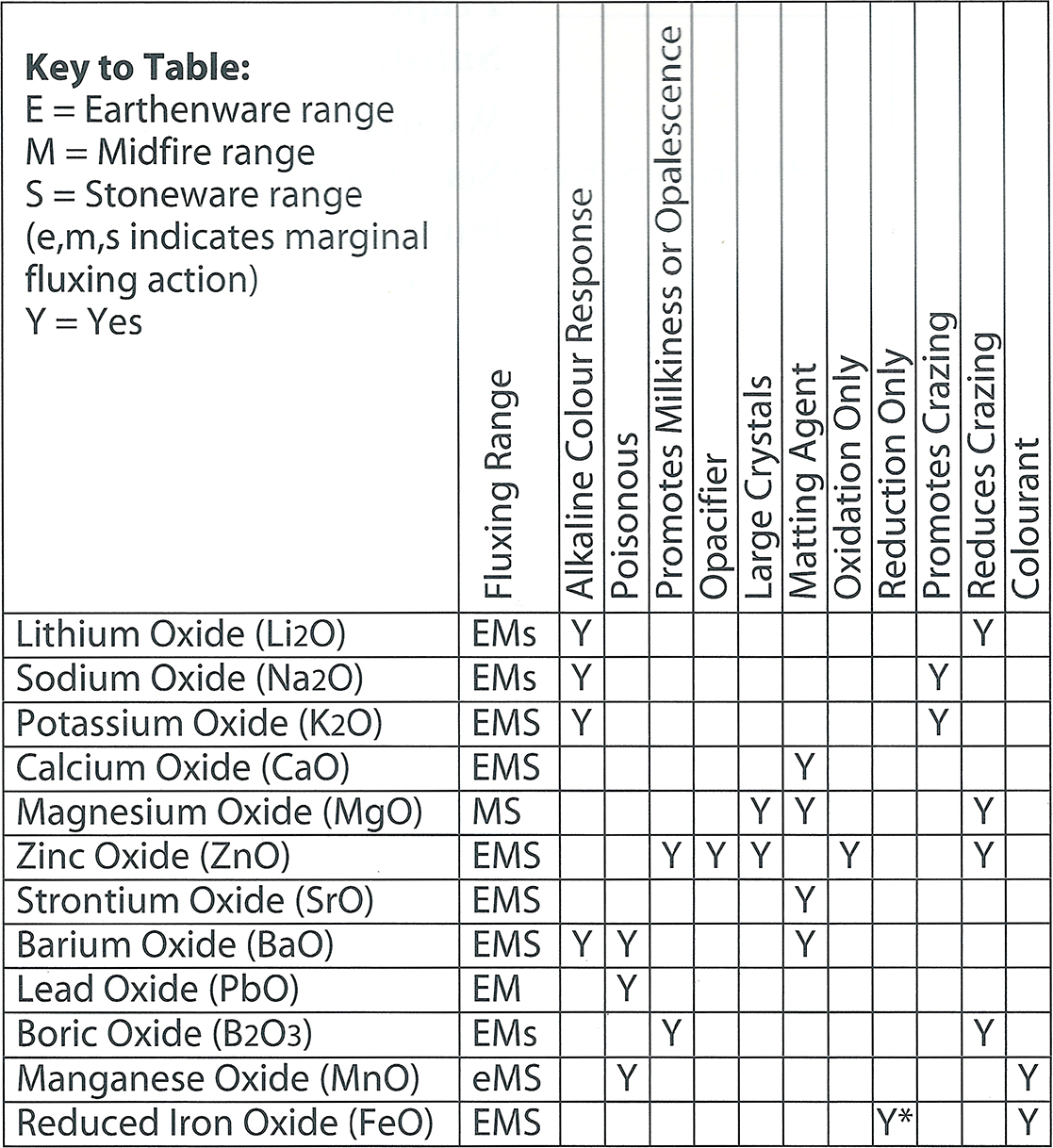

Flux Characteristics Chart

The following chart gives a summary of some outstanding properties of the main flux oxides. The real purpose of this diagram is to illustrate how we can build up a mental image of the properties of the fluxes. We can then better choose appropriate candidates from the List of Flux Materials (on the previous page) to promote particular characteristics, for example alkaline colour response, or large crystals. So this is not a complete list by any means. See the “Guided Tour” chapter for more detailed information on flux behaviour. Also see the references listed at the end of this chapter.

Table - Some Flux Characteristics

This table lists some of the properties for the main fluxes. Note the inclusion of two not mentioned previously, Manganese oxide (MnO) and reduced iron oxide (FeO). These are normally regarded as “colourants”. Many colouring oxides are fluxes but they are used only in small percentages in the glaze. However iron and manganese are both “weak” colourants and can be introduced in large amounts, large enough for their fluxing action to become important. Iron oxide has a special property - it acts as a flux only in reduction. Zinc oxide on the other hand is wasted in reduction; it changes to the metal and vaporizes, unless already incorporated in a glass or frit.

Proportions of Fluxes - Systematic Substitution

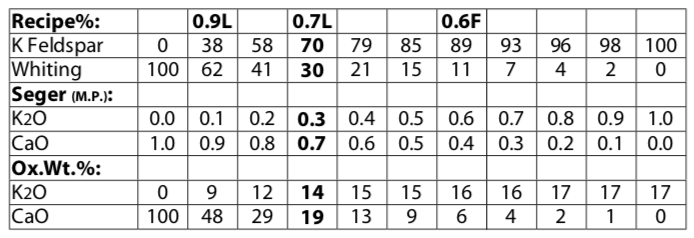

We have already mentioned the 0.7 Limestone Set. The range of possible flux sets is enormous, but we can get a handle on it by starting with this set and changing it. This set has the fluxes: \(0.3 K_{2}O + 0.7 CaO\) (in the Seger formula) and we saw in the Introduction chapter that this is a standard reliable middle-of-the-road set of fluxes for stoneware temperatures.

The first thing to change is the relative proportions of these two fluxes; we can go from one extreme where the only flux is \(K_{2}O\) (potash) to the other where the only flux is \(CaO\) (lime). The recipe for Glaze C in the 0.7 Limestone Set is 70% potash feldspar + 30% whiting. We would vary the proportion of feldspar-to-whiting to go from one extreme to another. The Limestone/Feldspar Series Table (page 46) shows the flux oxides and flux materials in Glaze C for a range of sets. Looking at the top 2 rows of figures, we can see that Glaze C goes from 100% whiting to 100% potash feldspar.

The middle two rows show that the series is divided into equal steps by molecular parts (M.P.) in the Seger formulae. Looking at the other two sets of numbers it is evident that this does not mean equal steps by weight parts. ”Recipe%” and ”Ox. Wt%” are both measures of weight, and they both have big jumps on the whiting end and small on the feldspar end of the table.

Divine Joke

*Table - Limestone/Feldspar Series

We will study the 0.7 Limestone Set (marked ”0.7L” above) in some detail in the Guided Tour chapter. Students wishing to study this series further could do the 0.9 Limestone Set (”0.9L”) and the 0.6 Feldspar Set (”0.6F”). This gives a reasonable spread.

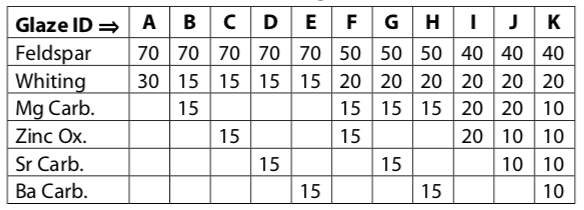

Looking at the 0.7 Limestone Set, we can begin to introduce other flux oxides. One way to do this is by replacing some of the \(CaO\) with for example \(ZnO\), \(MgO\), \(BaO\), \(SrO\). For example replace 15% of the whiting with 15% of zinc oxide or magnesium carbonate, barium carbonate or strontium carbonate. We can also replace some of the \(K_{2}O\) with \(Na_{2}O\) or \(Li_{2}O\). For example replace potash feldspar with a soda feldspar or nepheline syenite. If introducing lithium carbonate, use maximum 10% in Corner C; on a weight% basis it is a very powerful flux. (In general this method works well substituting fluxes on a weight-for-weight basis, but we can sometimes run into problems. To explore the theory of this we need to move into Seger formula or oxide weight percentage calculation, which is outside the scope of this book.)

Table - Introducing Other Fluxes

Study this table for a moment to see how we can start with the flux materials in the 0.7 Limestone Set (ID.”A”) and replace the feldspar and whiting with other flux materials - e.g. in “B” to “E” we are replacing half the whiting. The rest illustrate some of the feldspar being replaced as well. As we study this it becomes evident that this represents a very small proportion of the possible combinations; it becomes obvious that the possibilities are almost endless.

We are looking here at a vast landscape of glazes with every conceivable kind of aesthetic and functional real estate. The mind boggles at thinking how to begin exploring the possibilities. We are using here the 0.7 Limestone Sets as a sort of home base to begin our explorations. By exploring the Limestone/Feldspar Series Table we lay down a major thoroughfare through the topography. It took oriental potters hundreds of years to discover and explore, but standing as we do on the shoulders of the old potters, and living in an age of widespread information sharing we can now cover the same area in a couple of weeks. From this we can explore further into the landscape by introducing other fluxes one at a time as illustrated in the table above.

We can choose a safe conventional set of fluxes if we wish or alternatively choose fluxes at random, probably biasing towards high temperature fluxes if firing high, or vice versa if firing earthenware. We should not be afraid to take big risks, especially if we have a group helping and doing lots of sets. It’s quite unusual to get a set that doesn’t do something interesting in the right conditions on the right clay, and the more risk we take the greater the possibility of finding something exciting and new. We should push the boundaries, explore the fringes. But we mustn’t lose sight of our responsibility to use glazes appropriate and safe for whatever use we choose; whenever in doubt, do not use a glaze inside a functional vessel. If necessary read the safety guidelines given in the Appendix.

Remember there is no “right” firing cycle for a given set. A set that seems boring at first might produce brilliant things when we change firing conditions or clay body. The aim is to reveal exciting new glazes and discover important basic glaze principles. The new glazes seem to fall out of almost every set. The illustration of glaze principles emerges as a result of the orderly way the experiment is designed.

Firing Temperature - Choosing an Appropriate Set of Fluxes

It’s possible to come up with some rules of thumb for formulating a set of fluxes for different maturing temperatures. Some of the flux oxides are ineffective at low temperatures (e.g. MgO) and some burn out at high temperature (e.g.PbO).

All these suggestions are for Glaze C recipes, expressed as percentages.

| Stoneware: Cone 10 - 12 and higher | High \(R_{2}O\) Series | Medium Series | High \(RO\) Series |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potash Feldspar | 80 80 | 60 60 | 40 40 |

| Whiting (providing CaO) | 20 | 40 20 | 60 40 |

| RO Flux Materials containing one or more of MgO*, ZnO, BaO or SrO | 20 | 20 | 20 |

The mid-fire series are similar to the stoneware, but we replace the potash feldspar with nepheline syenite, plus 30 - 60% of frit. Check what is in your frit. For health reasons lead oxide (PbO) has not been included here.

| Midfire: Cone 5 - 6 and try firing as high as Cone 10 | High \(R_{2}O\) Series | Medium Series |

|---|---|---|

| Nepheline Syenite | 40 40 | 30 30 |

| Frit** (usually has some CaO) | 40 40 | 30 30 |

| Whiting (providing CaO) | 20 | 40 20 |

| RO Flux Materials containing one or more of MgO*, ZnO, BaO or SrO | 20 | 20 |

In the earthenware series, notice the similarity between the Frit/RO series and the High R2O Series in the stoneware series.

| Earthenware: Cone 06 - 02 and try firing as high as Cone 5 | Frit/RO Series |

|---|---|

| Frit** (usually has some CaO) | 80 80 |

| Whiting (providing CaO) | 20 |

| RO Flux Materials containing one or more of MgO***, ZnO, BaO or SrO | 20 |

So basically we are determining the temperature range of the set by deciding the main \(R_{2}O\)-type flux material we use, e.g. feldspar for high temperature, fit for low temperature and with nepheline syenite in between.

3. Family Set

Designing a Set Based on a Particular Glaze Recipe

If we wish to learn more about a favourite glaze we can design a grid set based on the flux materials and colourants/opacifiers it uses. The set will produce variants of the original but will look far beyond the original glaze. For example, the 0.7 Limestone Set is the family set for Mr. nishi’s Standard Cone 9~10 Limestone Glaze. The first step is to work out Glaze C. If this is done correctly we should find the original glaze (or very near to it) included in the grid somewhere. (Note the qualifications outlined in the box.)

To get Glaze C:

First we take the recipe and delete any clays (kaolin, china clay, ball clay etc.) and delete any silica, quartz, flint from the recipe. The remainder (just flux materials plus colourants &/or opacifiers) is Glaze C in a set that should encompass our original glaze somewhere. We can blend up the set in the usual way. We will usually need to convert this Glaze C to a % recipe so we can use the tables or the recipe grid to calculate the other glazes. (If we use the “Calculation Page” at the author’s web site, Glaze C does not have to be expressed as a percentage.)

Example

Original Glaze The following glaze called Periwinkle Blue and attributed to Pete Pinnell was mailed to ClayArt:

1% Lithium Carbonate

20% Strontium Carbonate

60% Nepheline Syenite

10% Ball Clay

9% Flint

+4% Copper Carbonate

+0.15% Cobalt Carbonate

This is an interesting blue glaze. A grid was designed using the set of fluxes and colourants from the glaze.

Producing Glaze C for this set:

Remove the clay (here it’s ball clay*) and the added silica (here it’s called flint) and glaze C is:

1 Lithium Carbonate

20 Strontium Carbonate

60 Nepheline Syenite

+4% Copper Carbonate

+0.15% Cobalt Carbonate

This recipe can be entered into the “Calculation Page” to produce all the recipes, or if we decide to use the Recipe Tables, or the Recipe Grid method, we need to first convert this recipe to percentage figures. Percentage calculation is explained in the Appendix. The percentage version of glaze C here becomes:

1.2% Lithium Carbonate

24.7% Strontium Carbonate

74.1% Nepheline Syenite

+4% Copper Carbonate

+0.15% Cobalt Carbonate

Use this recipe to obtain the 4 Corner Glazes for blending and also any of the glazes that you find interesting. Pete’s original glaze would have been somewhere around No. 27 or 26.

Developing the Set Further

The set above was mostly immature or dry at Cone 6. To get more glazes to mature at midfire temperatures, 10% of frit was added to Glaze C, mostly at the expense of the nepheline syenite. Also lithium carbonate was increased from 1.2% to 2%. Lithium is a powerful flux, and these two changes have caused a significant increase in the number of glazes maturing.

The new Corner C Glaze:

10% Frit 3134

65% Nepheline Syenite

23% Strontium Carbonate

2% Lithium Carbonate

+4% Copper Carbonate

+0.15% Cobalt Carbonate

(See Family Set page in the Guided Tour chapter for a photo of this set.)

4. Random Choice

There is not much to be said for this method which is more of a philosophical than a technical approach to developing glazes. The chances of discovering new and exciting glazes are high, as are the chances of a disappointing set. The suggested maximum values for any flux material in Glaze C should help avoid disasters; see the List of Flux Materials in this Chapter.