1 Gradients and Variables

The Holy Grail

To some extent every problem contains its own solution, and every stumbling beginning contains the seeds of success. Every firing can be an experiment that points the way to the solution of problems, or further evolution. There’s a kind of paradox here that relates to the pursuit of uniformity. In industrial ceramics, the engineers are usually trying for total control, and to have kilns that fire with perfect uniformity. Most artist potters on the other hand regard control as just one tool that may be used in the pursuit of artistic excellence.

This attitude has an unexpected technological benefit. Imagine 100 identical pots being subjected to identical firing conditions. Any mistake that occurred would show on all the pieces. Despite the occasional paranoia that we have personally drawn this short straw, what usually happens is that problems appear only on some pieces and in some places. A close examination of what is different between success and failure allows us to guess at theories about the nature of the problem and its solution. So the lack of uniformity is revealing variables that can lead us to better results. There’s a sort of Darwinian selection process going on here, with the variation being caused by the crude technology, and the selection process being decided by human choice.

In China and Korea stoneware glazes first developed as a result of potters observing the results of a very haphazard technology. In the first place they noticed that the pots that got hottest became stronger and non-porous. This was fairly easy for an observant potter to discover with such difficult and uneven kilns; it was obvious the pots next to the firebox became tougher. So as a result of the inefficiency of the kiln, a temperature gradient well understood by the potter was pointing the way to better pots. To get stronger and less porous pots they fired higher and higher. Eventually something interesting happened; a shiny, runny glaze appeared on the front of pots near the firebox. Careful observation through the kiln as they unloaded the fired pots would have confirmed that it was simply melted ash. There would have been a gradient through the kiln going from near the firebox where the ash melted to where the ash was completely unmelted, with every stage in between.

Any sort of gradient can provide useful information; we artificially create a glaze composition gradient when we create a line blend. There are all sorts of gradients through the kiln and across a pot. They are caused by variations in temperature and kiln atmosphere, heating and cooling rate, glaze thickness, wood ash and vapour deposit. By observing where changes occur and where they don’t the potter is able to detect subtle variables that can eliminate a problem or promote a benefit.

Thinking further about this built-in evolutionary trend in any primitive technology we are able to see also how it leads in the longer term to cycles of building up followed by stagnation, devolution and then regeneration. Thinking back to the example of the ancient potters using the gradients in the kilns to guide their improvements, we can see that for many it has now evolved to the opposite end of the scale, where a high degree of control and predictability is possible by many potters. For some, the reason for making pots is to make money. This guides the hand towards choice of reliable and reproducible methods and materials.

Sometimes we find ourselves doing this for sheer economic necessity in the effort to avoid the starving artist syndrome. But for those drawn to ceramics out of a love of creativity, there is a sting here. Just when we are getting things under control and could gain a little wealth, stability, certainty in our lives, something happens and we feel bored. This seems unfair, but upon reflection we discover that it is inevitable. As sensitive and creative people, we are excited by discovery, revelation and insight whether from our own efforts or the efforts of others. When something is predictable, there is no discovery, no insight, and no revelation… just a predictable variation on an old tune. Boring!

Once our kilns and materials and techniques produce the same perfect thing every time, not only does it become boring (except for the thought of the money it might bring!) but also we are suddenly not learning anything from each batch of pots we fire. We are cut off from a natural source of evolution. If we want improvement we have to consciously conduct a research program.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with all this, but something that probably started with idealism and great enthusiasm can thereby become tiresome. We need a balance. And the balance comes from a return to basics. We need to reclaim the excitement of discovery, and the satisfaction of taking big risks and being lucky. And so we start anew like the old potters with their primitive kilns and glazes and the cycle begins again… we arise phoenix-like from the ashes of certainty and boredom to reclaim life.

Some have a problem with this treadmill. What is the point? Will we ever achieve true satisfaction and happiness and the perfect glaze?! Yes indeed! But we must be aware that we never stop growing. The Holy Grail once achieved does not guarantee eternal bliss! Once obtained, perfection provides the launching platform for the next endeavour. It’s the old story of the journey being more important than the destination - and it generates meaning in our lives. And attitude is everything! The ancient potter on seeing the runny shiny stuff on some of his pots could have viewed it either way: an annoying flaw or a gift of possibilities - a doorway to be ignored or entered through.

Isolating Variables

Line Blends

We have seen above how gradients can reveal important variables. The gradient makes the variable visible and tangible. We can see the effect of the variable with our own eyes, and seeing the effects, we can deduce causes. This helps point the way to better results. Experimenting with glazes we can use line blends to artificially create gradients of glaze composition. Line blending is one of the basic experimental procedures that the ceramic artist needs to understand. This is not difficult, but by putting a little thought into the experimental design we can get more from the results.

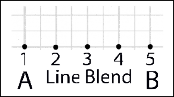

A line blend is a series of glazes obtained by blending two glazes together. The compositions of the blended glazes are intermediate to the two original glazes. In our diagrams we will represent a line blend as a series of dots as illustrated here.

If possible we design our line blend so there is just one variable. If we do this, we get more than just a range of glazes; we can see a clear indication of the effect of the one chosen variable, without being confused by others.

So to come to grips with fundamental cause-and-effect principles we need to design our experiments so we can isolate or separate out the variables. We can understand this point with a few examples of different sorts of line blends…

Different Kinds of Line Blends

- Addition Line blend - 5 Recipes

Glaze No: 1 2 3 4 5 Glaze X 100 100 100 100 100 Colourant 0 2 4 6 8 The only variable here is the colourant.

- Crossover Line Blend - 5 Recipes

Glaze No: 1 2 3 4 5 Glaze A 100 75 50 25 0 Glaze B 0 25 50 75 100

With a crossover line blend there is no guarantee of being able to neatly separate out a single variable. After all, the two glazes could be completely unrelated, and we might be dealing with a dozen variables from the two glazes all changing at once.

If however the two glazes are carefully chosen, we can have a crossover blend with just one variable. See the example following in “Working Out the Recipes in a Line Blend”.

Working Out the Recipes in a Line Blend

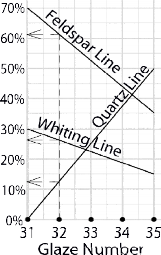

The simplest way to visualize the maths of a line blend is to plot one out on a piece of graph paper. Consider the two recipes:

| Glaze Name | Glaze C | Glaze D |

| Feldspar | 70 | 35 |

| Whiting | 30 | 15 |

| Quartz | 0 | 50 |

Draw the “Feldspar Line” from 70% above C to 35% above D (see graph). Similarly draw in the Whiting and the Quartz Lines using the figures from the table.

Five glazes occur at equal intervals along the horizontal axis. If for example we wish to get the recipe for Glaze 32, we follow the dotted line up from 32 and see at what % it intersects the three sloping lines. We read the % figures at the arrows:

Glaze No. 32:

61\(\frac{1}{4}\)% Feldspar

26\(\frac{1}{4}\)% Whiting

12\(\frac{1}{2}\)% Quartz

Check that the figures add up to 100% or very nearly. We can achieve this accuracy if the graph paper is large enough. Use at least an A4 or standard Letter size.

Note that as well as the original 5 recipes we can read off the percentages for glazes that fall between them.

Biaxial Blends

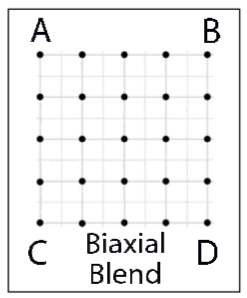

A biaxial blend is a two-dimensional experiment in a grid format. The two dimensions allow us to separate out a maximum of two independent variables. Any of the rows of glazes horizontally or vertically is a line blend. In the example, the whole set of 25 glazes can be prepared by blending from the four “corner glazes” A, B, C and D. The standard “grid” used in the experiments in this book is a 5 X 7 biaxial blend, totaling 35 glazes.

Blending and Trending - A Puzzle

In a line blend we will often see a steady trend in glaze characteristics from one end to the other. Our common sense tells us that this should be so. However this is not always the case. It is possible for example to blend between two stiff matt glazes hoping for a combination of desirable properties somewhere in the middle only to find the intermediate glazes are shiny and runny. This will happen if we choose to blend between two glazes on opposite sides of a strong eutectic trough (see references). In some cases where we are blending from one colourant to another the colours blend as colour theory would predict. But this also can give surprises. For example, mixing manganese and chrome oxides will not produce an intermediate colour. Instead we get dark opaque colours resulting from a chemical reaction between the colourants.

In the next chapter, we see how to incorporate the idea of isolating variables into a coherent standardized experimental method