5. Variation

The variance

Watch this video before beginning.

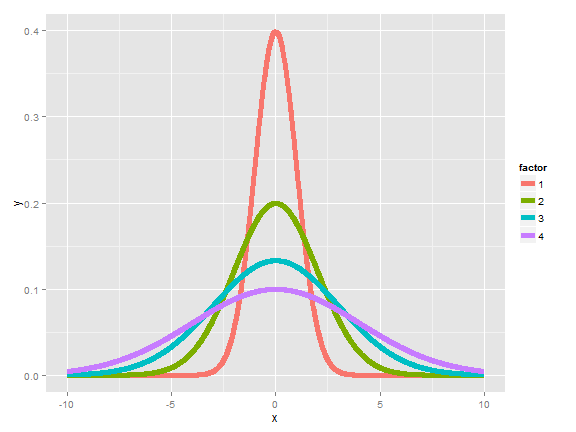

Recall that the mean of distribution was a measure of its center. The variance, on the other hand, is a measure of spread. To get a sense, the plot below shows a series of increasing variances.

We saw another example of how variances changed in the last chapter when we looked at the distribution of averages; they were always centered at the same spot as the original distribution, but are less spread out. Thus, it is less likely for sample means to be far away from the population mean than it is for individual observations. (This is why the sample mean is a better estimate than the population mean.)

If  is a random variable with mean

is a random variable with mean  , the variance of

, the variance of

is defined as

is defined as

![Var(X) = E[(X - \mu)^2] = E[X^2] - E[X]^2.](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_158.png)

The rightmost equation is the shortcut formula that is almost always used

for calculating variances in practice.

Thus the variance is the expected (squared) distance from the mean. Densities

with a higher variance are more spread out than densities with

a lower variance. The square root of the variance is called the

standard deviation. The main benefit of working with standard deviations

is that they have the same units as the data, whereas the variance has the

units squared.

In this class, we’ll only cover a few basic examples for calculating a variance. Otherwise, we’re going to use the ideas without the formalism. Also remember, what we’re talking about is the population variance. It measures how spread out the population of interest is, unlike the sample variance which measures how spread out the observed data are. Just like the sample mean estimates the population mean, the sample variance will estimate the population variance.

Example

What’s the variance from the result of a toss of a die? First recall that ![E[X] = 3.5](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_159.png) , as we discussed in the previous lecture.

Then let’s calculate the other bit of information that we need,

, as we discussed in the previous lecture.

Then let’s calculate the other bit of information that we need, ![E[X^2]](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_160.png) .

.

![E[X^2] = 1 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 2 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 3 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 4 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 5 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 6 ^ 2 \times \frac{1}{6} = 15.17](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_161.png)

Thus now we can calculate the variance as:

![Var(X) = E[X^2] - E[X]^2 \approx 2.92.](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_162.png)

Example

What’s the variance from the result of the toss of a

(potentially biased) coin with probability of heads (1) of  ? First recall that

? First recall that

![E[X] = 0 \times (1 - p) + 1 \times p = p.](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_164.png) Secondly, recall that since

Secondly, recall that since  is either 0 or 1,

is either 0 or 1,

. So we know that:

. So we know that:

![E[X^2] = E[X] = p.](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_167.png)

Thus we can now calculate the variance of a coin flip as

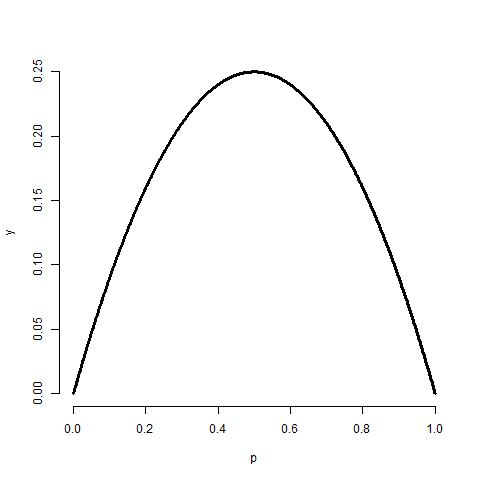

![Var(X) = E[X^2] - E[X]^2 = p - p^2 = p(1 - p).](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_168.png) This is a well known formula, so it’s worth committing

to memory. It’s interesting to note that this function is

maximized at

This is a well known formula, so it’s worth committing

to memory. It’s interesting to note that this function is

maximized at  . The plot below shows this by

plotting

. The plot below shows this by

plotting  by

by  .

.

= seq(0 , 1, length = 1000)

y = p * (1 - p)

plot(p, y, type = "l", lwd = 3, frame = FALSE)

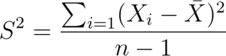

The sample variance

The sample variance is the estimator of the population variance. Recall that the population variance is the expected squared deviation around the population mean. The sample variance is (almost) the average squared deviation of observations around the sample mean. It is given by

The sample standard deviation is the square root of the sample variance.

Note again that

the sample variance is almost, but not quite, the average squared deviation from

the sample mean since we divide by  instead of

instead of

. Why do we do this you might ask? To answer that question

we have to think in the terms of simulations. Remember that the

sample variance is a random variable, thus it has a distribution

and that distribution has an associated population mean. That

mean is the population variance that we’re trying to estimate

if we divide by

. Why do we do this you might ask? To answer that question

we have to think in the terms of simulations. Remember that the

sample variance is a random variable, thus it has a distribution

and that distribution has an associated population mean. That

mean is the population variance that we’re trying to estimate

if we divide by  rather than

rather than  .

.

It is also nice that as we collect more data the distribution of the sample variance gets more concentrated around the population variance that it’s estimating.

Simulation experiments

Watch this video before beginning.

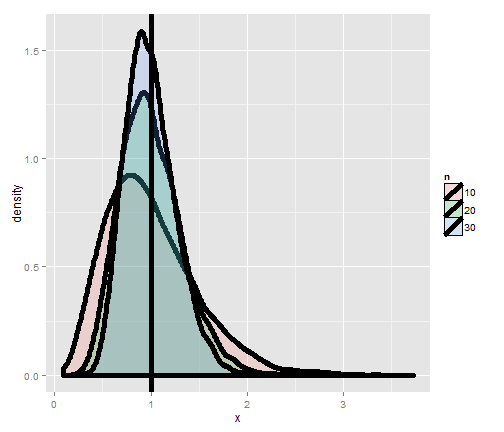

Simulating from a population with variance 1

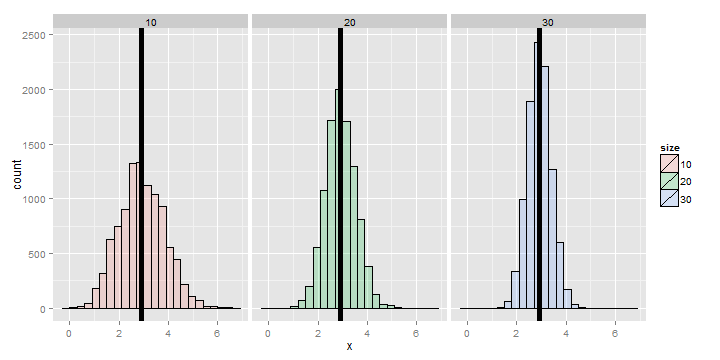

Let’s try simulating collections of standard normals and taking the variance. If we repeat this over and over, we get a sense of the distribution of sample variances variances.

Notice that these histograms are always centered in the same spot, 1. In other words, the sample variance is an unbiased estimate of the population variances. Notice also that they get more concentrated around the 1 as more data goes into them. Thus, sample variances comprised of more observations are less variable than sample variances comprised of fewer.

Variances of x die rolls

Let’s try the same thing, now only with die rolls instead of simulating standard normals. In this experiment, we simulated samples of die rolls, took the variance and then repeated that process over and over. What is plotted are histograms of the collections of sample variances.

Recall that we calculated the variance of a die roll as 2.92 earlier on in this chapter. Notice each of the histograms are centered there. In addition, they get more concentrated around 2.92 as more the variances are comprised of more dice.

The standard error of the mean

At last, we finally get to a perhaps very surprising (and useful) fact:

how to estimate the variability of the mean of a sample, when we only get to observe

one realization. Recall that the average of random sample from a population

is itself a random variable having a distribution, which in simulation

settings we can explore by repeated sampling averages. We know that this

distribution is centered around the population mean,

![E[\bar X] = \mu](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_177.png) . We also know the variance of the distribution

of means of random samples.

. We also know the variance of the distribution

of means of random samples.

The variance of the sample mean is:  where

where  is the variance of the population being sampled

from.

is the variance of the population being sampled

from.

This is very useful, since we don’t have repeat sample means

to get its variance directly using the data. We already know a good estimate of

via the sample variance. So, we can get a good estimate

of the variability of the mean, even though we only get to observe 1 mean.

via the sample variance. So, we can get a good estimate

of the variability of the mean, even though we only get to observe 1 mean.

Notice also this explains why in all of our simulation experiments the variance of the sample mean kept getting smaller as the sample size increased. This is because of the square root of the sample size in the denominator.

Often we take the square root of the variance of the mean to get the standard deviation of the mean. We call the standard deviation of a statistic its standard error.

Summary notes

- The sample variance,

, estimates the population variance,

, estimates the population variance,  .

. - The distribution of the sample variance is centered around

.

. - The variance of the sample mean is

.

.

- Its logical estimate is

.

. - The logical estimate of the standard error is

.

.

- Its logical estimate is

-

, the standard deviation, talks about how variable the population is.

, the standard deviation, talks about how variable the population is. -

, the standard error, talks about how variable averages of random

samples of size

, the standard error, talks about how variable averages of random

samples of size  from the population are.

from the population are.

Simulation example 1: standard normals

Watch this video before beginning.

Standard normals have variance 1. Let’s try sampling

means of  standard normals. If our theory is correct, they should

have standard deviation

standard normals. If our theory is correct, they should

have standard deviation

> nosim <- 1000

> n <- 10

## simulate nosim averages of 10 standard normals

> sd(apply(matrix(rnorm(nosim * n), nosim), 1, mean))

[1] 0.3156

## Let's check to make sure that this is sigma / sqrt(n)

> 1 / sqrt(n)

[1] 0.3162

So, in this simulation, we simulated 1000 means of 10 standard normals. Our

theory says the standard deviation of averages of 10 standard normals must

be  . Taking the standard deviation of the 10000 means yields

nearly exactly that. (Note that it’s only close, 0.3156 versus 0.31632.

To get it to be exact, we’d have to simulate

infinitely many means.)

. Taking the standard deviation of the 10000 means yields

nearly exactly that. (Note that it’s only close, 0.3156 versus 0.31632.

To get it to be exact, we’d have to simulate

infinitely many means.)

Simulation example 2: uniform density

Standard uniforms have variance  . Our theory mandates

that means of random samples of

. Our theory mandates

that means of random samples of  uniforms

have sd

uniforms

have sd  . Let’s try it with a simulation.

. Let’s try it with a simulation.

> nosim <- 1000

> n <- 10

> sd(apply(matrix(runif(nosim * n), nosim), 1, mean))

[1] 0.09017

> 1 / sqrt(12 * n)

[1] 0.09129

Simulation example 3: Poisson

Poisson(4) random variables have variance  . Thus means of

random samples of

. Thus means of

random samples of  Poisson(4)

should have standard deviation

Poisson(4)

should have standard deviation  . Again let’s try it out.

. Again let’s try it out.

> nosim <- 1000

> n <- 10

> sd(apply(matrix(rpois(nosim * n, 4), nosim), 1, mean))

[1] 0.6219

> 2 / sqrt(n)

[1] 0.6325

Simulation example 4: coin flips

Our last example is an important one. Recall that the variance of a

coin flip is  . Therefore the standard deviation of the average

of

. Therefore the standard deviation of the average

of  coin flips should be

coin flips should be  .

.

Let’s just do the simulation with a fair coin. Such coin

flips have variance 0.25. Thus means of

random samples of  coin flips have sd

coin flips have sd  .

Let’s try it.

.

Let’s try it.

> nosim <- 1000

> n <- 10

> sd(apply(matrix(sample(0 : 1, nosim * n, replace = TRUE),

nosim), 1, mean))

[1] 0.1587

> 1 / (2 * sqrt(n))

[1] 0.1581

Data example

Now let’s work through a data example to show how the standard error of the

mean is used in practice. We’ll use the father.son height data from Francis

Galton.

library(UsingR); data(father.son);

x <- father.son$sheight

n<-length(x)

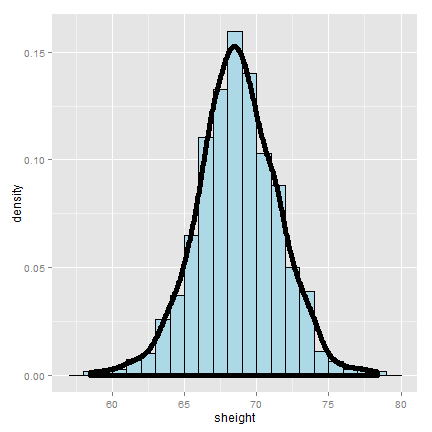

Here’s a histogram of the sons’ heights from the dataset. Let’ calculate different variances and interpret them in this context.

>round(c(var(x), var(x) / n, sd(x), sd(x) / sqrt(n)),2)

[1] 7.92 0.01 2.81 0.09

The first number, 7.92, and its square root, 2.81, are the estimated variance

and standard deviation of the sons’ heights. Therefore, 7.92 tells us exactly how variable

sons’ heights were in the data and estimates how variable sons’ heights are

in the population. In contrast 0.01, and the square root 0.09, estimate how

variable averages of  sons’ heights are.

sons’ heights are.

Therefore, the smaller numbers discuss the precision of our estimate of the mean of sons’ heights. The larger numbers discuss how variable sons’ heights are in general.

Summary notes

- The sample variance estimates the population variance.

- The distribution of the sample variance is centered at what its estimating.

- It gets more concentrated around the population variance with larger sample sizes.

- The variance of the sample mean is the population variance

divided by

.

.

- The square root is the standard error.

- It turns out that we can say a lot about the distribution of averages from random samples, even though we only get one to look at in a given data set.

Exercises

- If I have a random sample from a population, the sample variance is an estimate of?

- The population standard deviation.

- The population variance.

- The sample variance.

- The sample standard deviation.

- The distribution of the sample variance of a random sample from a population is centered at what?

- The population variance.

- The population mean.

- I keep drawing samples of size

from a population with variance

from a population with variance  and taking their average. I do this thousands of times. If I were to take the variance of the collection of averages, about what would it be?

and taking their average. I do this thousands of times. If I were to take the variance of the collection of averages, about what would it be? - You get a random sample of

observations from a population and take their average. You would like to estimate the variability of averages of $$n$$ observations from this population to better understand how precise of an estimate it is. Do you need to repeated collect averages to do this?

observations from a population and take their average. You would like to estimate the variability of averages of $$n$$ observations from this population to better understand how precise of an estimate it is. Do you need to repeated collect averages to do this?

- No, we can multiply our estimate of the population variance by

to get a good estimate of the variability of the average.

to get a good estimate of the variability of the average. - Yes, you have to get repeat averages.

- No, we can multiply our estimate of the population variance by

- A random variable takes the value -4 with probability .2 and 1 with probability .8. What is the variance of this random variable? Watch a video solution to this problem. and look at a version with a worked out solution.

- If

and

and  are comprised of n iid random variables arising from distributions

having means

are comprised of n iid random variables arising from distributions

having means  and

and  , respectively and common variance

, respectively and common variance

what is the variance

what is the variance  ?

Watch a video solution to this problem here and see a typed up solution here

?

Watch a video solution to this problem here and see a typed up solution here

- Let

be a random variable having standard deviation

be a random variable having standard deviation  . What can

be said about the variance of

. What can

be said about the variance of  ? Watch a video solution to this

problem here and

typed up solutions here.

? Watch a video solution to this

problem here and

typed up solutions here. - Consider the following pmf given in R by the code

p <- c(.1, .2, .3, .4)and ‘x <- 2 : 5`. What is the variance? Watch a video solution to this problem here and here is the problem worked out. - If you roll ten standard dice, take their average, then repeat this process over and over and construct a histogram, what would be its variance expressed to 3 decimal places? Watch a video solution here and see the text here.