9. Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis testing is concerned with making decisions using data.

Hypothesis testing

Watch this video before beginning.

To make decisions using data, we need to characterize the kinds of conclusions

we can make. Classical hypothesis testing is concerned with deciding between

two decisions (things get much harder if there’s more than two).

The first, a null hypothesis is specified that represents the status quo.

This hypothesis is usually labeled,  . This is what we assume

by default. The alternative or

research hypothesis is what we require evidence to conclude. This hypothesis is usually labeled,

. This is what we assume

by default. The alternative or

research hypothesis is what we require evidence to conclude. This hypothesis is usually labeled,  or sometimes

or sometimes  (or some other number other than 0).

(or some other number other than 0).

So to reiterate, the null hypothesis is assumed true and statistical evidence is required to reject it in favor of a research or alternative hypothesis

Example

A respiratory disturbance index (RDI) of more than 30 events / hour, say, is considered evidence of severe sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Suppose that in a sample of 100 overweight subjects with other risk factors for sleep disordered breathing at a sleep clinic, the mean RDI was 32 events / hour with a standard deviation of 10 events / hour.

We might want to test the hypothesis that

versus the hypothesis

where  is the population mean RDI. Clearly, somehow we must

figure out a way to decide between these hypotheses using the observed data,

particularly the sample mean.

is the population mean RDI. Clearly, somehow we must

figure out a way to decide between these hypotheses using the observed data,

particularly the sample mean.

Before we go through the specifics, let’s set up the central ideas.

Types of errors in hypothesis testing

The alternative hypotheses are typically of the form

of the true mean being  ,

,  or

or  to the hypothesized

mean, such as

to the hypothesized

mean, such as  from our example. The null typically

sharply specifies the mean, such as

from our example. The null typically

sharply specifies the mean, such as  in our example.

More complex null hypotheses are possible, but are typically

covered in later courses.

in our example.

More complex null hypotheses are possible, but are typically

covered in later courses.

Note that there are four possible outcomes of our statistical decision process:

| Truth | Decide | Result |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Correctly accept null |

|

|

Type I error |

|

|

Correctly reject null |

|

|

Type II error |

We will perform hypothesis testing by forcing the probability of a Type I error to be small. This approach consequences, which we can discuss with an analogy to court cases.

Discussion relative to court cases

Consider a court of law and a criminal case. The null hypothesis is that the defendant is innocent. The rules requires a standard on the available evidence to reject the null hypothesis (and the jury to convict). The standard is specified loosely in this case, such as convict if the defendant appears guilty “Beyond reasonable doubt”. In statistics, we can be mathematically specific about our standard of evidence.

Note the consequences of setting a standard. If we set a low standard, say convicting only if there circumstantial or greater evidence, then we would increase the percentage of innocent people convicted (type I errors). However, we would also increase the percentage of guilty people convicted (correctly rejecting the null).

If we set a high standard, say the standard of convicting if the jury has “No doubts whatsoever”, then we increase the the percentage of innocent people let free (correctly accepting the null) while we would also increase the percentage of guilty people let free (type II errors).

Building up a standard of evidence

Watch this video before beginning.

Consider our sleep example again. A reasonable strategy would reject the null hypothesis if

the sample mean,  , was larger than some constant, say

, was larger than some constant, say  .

Typically,

.

Typically,  is chosen so that the probability of a Type I

error, labeled

is chosen so that the probability of a Type I

error, labeled  , is

, is  (or some other relevant constant)

To reiterate,

(or some other relevant constant)

To reiterate,  Type I error rate = Probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when, in fact, the null hypothesis is correct

Type I error rate = Probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when, in fact, the null hypothesis is correct

Let’s see if we can figure out what  has to be.

The standard error of the mean is

has to be.

The standard error of the mean is  .

Furthermore, under

.

Furthermore, under  we know that

we know that  (at least approximately) via the CLT.

We want to chose

(at least approximately) via the CLT.

We want to chose  so that:

so that:

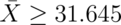

The 95th percentile of a normal distribution is 1.645

standard deviations from the mean. So, if  is set 1.645 standard deviations from the mean, we should be set

since the probability of getting a sample mean that large is only

5%. The 95th percentile from a

is set 1.645 standard deviations from the mean, we should be set

since the probability of getting a sample mean that large is only

5%. The 95th percentile from a  is:

is:

So the rule “Reject  when

when  ”

has the property that the probability of rejection

is 5% when

”

has the property that the probability of rejection

is 5% when  is true.

is true.

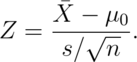

In general, however, we don’t convert  back to the original scale.

Instead, we calculate how many standard errors the observed mean is

from the hypothesized mean

back to the original scale.

Instead, we calculate how many standard errors the observed mean is

from the hypothesized mean

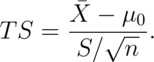

This is called a Z-score. We can compare this statistic to standard normal quantiles.

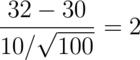

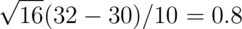

To reiterate, the Z-score is how many standard errors the sample mean is above the hypothesized mean. In our example:

Since 2 is greater than 1.645 we would reject. Setting the rule “We reject

if our Z-score is larger than 1.645” controls the Type I error rate at 5%.

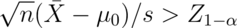

We could write out a general rule for this alternative hypothesis as

reject whenever  where

where

is the desired Type I error rate.

is the desired Type I error rate.

Because the Type I error rate was controlled to be small, if we reject we know that one of the following occurred:

- the null hypothesis is false,

- we observed an unlikely event in support of the alternative even though the null is true,

- our modeling assumptions are wrong.

The third option can be difficult to check and at some level all bets are off depending on how wrong we are about our basic assumptions. So for this course, we speak of our conclusions under the assumption that our modeling choices (such as the iid sampling model) are correct, but do so wide eyed acknowledging the limitations of our approach.

General rules

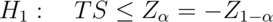

We developed our test for one possible alternatives. Here’s some general rules for the three most important alternatives.

Consider the  test for

test for  versus:

versus:

,

,  ,

,

. Our test statistic

. Our test statistic

We reject the null hypothesis when:

,

,

,

,

respectively.

Summary notes

- We have fixed

to be low, so if we reject

to be low, so if we reject  (either

our model is wrong) or there is a low probability that we have made

an error.

(either

our model is wrong) or there is a low probability that we have made

an error. - We have not fixed the probability of a type II error,

;

therefore we tend to say “Fail to reject

;

therefore we tend to say “Fail to reject  ” rather than

accepting

” rather than

accepting  .

. - Statistical significance is no the same as scientific significance.

- The region of TS values for which you reject

is called the

rejection region.

is called the

rejection region. - The

test requires the assumptions of the CLT and for

test requires the assumptions of the CLT and for  to be large enough

for it to apply.

to be large enough

for it to apply. - If

is small, then a Gosset’s t test is performed exactly in the same way,

with the normal quantiles replaced by the appropriate Student’s t quantiles and

is small, then a Gosset’s t test is performed exactly in the same way,

with the normal quantiles replaced by the appropriate Student’s t quantiles and

df.

df. - The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false is called power

- Power is a used a lot to calculate sample sizes for experiments.

Example reconsidered

Watch this video before beginning.

Consider our example again. Suppose that  (rather than

(rather than

). The statistic

). The statistic

follows a t distribution with 15 df under  .

.

Under  , the probability that it is larger

that the 95th percentile of the t distribution is 5%.

The 95th percentile of the T distribution with 15

df is 1.7531 (obtained via

, the probability that it is larger

that the 95th percentile of the t distribution is 5%.

The 95th percentile of the T distribution with 15

df is 1.7531 (obtained via r qt(.95, 15)).

Assuming that everything but the sample size is the same, our test statistic is now  . Since 0.8 is not larger than 1.75,

we now fail to reject.

. Since 0.8 is not larger than 1.75,

we now fail to reject.

Two sided tests

In many settings, we would like to reject if the true mean is different

than the hypothesized, not just larger or smaller. I other words, we would

reject the null hypothesis if in fact the sample mean was much larger or smaller

than the hypothesized mean.

In our example, we want to test the alternative  .

.

We will reject if the test statistic,  , is either too large or

too small. Then we want the probability of rejecting under the

null to be 5%, split equally as 2.5% in the upper

tail and 2.5% in the lower tail.

, is either too large or

too small. Then we want the probability of rejecting under the

null to be 5%, split equally as 2.5% in the upper

tail and 2.5% in the lower tail.

Thus we reject if our test statistic is larger

than qt(.975, 15) or smaller than qt(.025, 15).

This is the same as saying: reject if the

absolute value of our statistic is larger than

qt(0.975, 15) = 2.1314.

In this case, since our test statistic is 0.8, which is smaller than 2.1314, we fail to reject the two sided test (as well as the one sided test).

If you fail to reject the one sided test, then you would fail to reject the two sided test. Because of its larger rejection region, two sided tests are the norm (even in settings where a one sided test makes more sense).

T test in R

Let’s try the t test on the pairs of fathers and sons in Galton’s data.

> library(UsingR); data(father.son)

> t.test(father.son$sheight - father.son$fheight)

One Sample t-test

data: father.son$sheight - father.son$fheight

t = 11.79, df = 1077, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.831 1.163

sample estimates:

mean of x

0.997

Connections with confidence intervals

Consider testing  versus

versus  .

Take the set of all possible values for which you fail to reject

.

Take the set of all possible values for which you fail to reject  ,

this set is a

,

this set is a  confidence interval for

confidence interval for  .

.

The same works in reverse; if a  interval

contains

interval

contains  , then we fail to reject

, then we fail to reject  .

.

In other words, two sided tests and confidence intervals agree.

Two group intervals

Doing group tests is now straightforward given that we’ve already covered independent group T intervals. Our rejection rules are the same, the only change is how the statistic is calculated. However, the form is familiar:

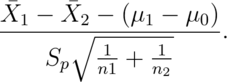

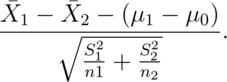

Consider now testing  . Our statistic is

. Our statistic is

For the equal variance case and and

Let’s just go through an example.

Example chickWeight data

Recall that we reformatted this data as follows

library(datasets); data(ChickWeight); library(reshape2)

##define weight gain or loss

wideCW <- dcast(ChickWeight, Diet + Chick ~ Time, value.var = "weight")

names(wideCW)[-(1 : 2)] <- paste("time", names(wideCW)[-(1 : 2)], sep = "")

library(dplyr)

wideCW <- mutate(wideCW,

gain = time21 - time0

)

> wideCW14 <- subset(wideCW, Diet %in% c(1, 4))

> t.test(gain ~ Diet, paired = FALSE,

+ var.equal = TRUE, data = wideCW14)

Two Sample t-test

data: gain by Diet

t = -2.725, df = 23, p-value = 0.01207

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-108.15 -14.81

sample estimates:

mean in group 1 mean in group 4

136.2 197.7

Exact binomial test

Recall this problem. Suppose a friend has 8 children, 7 of which are girls and none are twins.

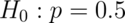

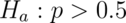

Perform the relevant hypothesis test.  versus

versus  .

.

What is the relevant rejection region so that the probability of rejecting is (less than) 5%?

| Rejection region | Type I error rate |

|---|---|

| [0 : 8] | 1 |

| [1 : 8] | 0.9961 |

| [2 : 8] | 0.9648 |

| [3 : 8] | 0.8555 |

| [4 : 8] | 0.6367 |

| [5 : 8] | 0.3633 |

| [6 : 8] | 0.1445 |

| [7 : 8] | 0.0352 |

| [8 : 8] | 0.0039 |

Thus if we reject under 7 or 8 girls, we will have a less than 5% chance of rejecting under the null hypothesis.

It’s impossible to get an exact 5% level test for this case due to the discreteness of the binomial. The closest is the rejection region [7 : 8]. Further note that an alpha level lower than 0.0039 is not attainable. For larger sample sizes, we could do a normal approximation.

Extended this test to two sided test isn’t obvious.

Given a way to do two sided tests, we could take the set of values of  for which we fail to reject to get an exact binomial confidence interval (called the Clopper/Pearson interval, by the way). We’ll cover two sided versions of this

test when we cover P-values.

for which we fail to reject to get an exact binomial confidence interval (called the Clopper/Pearson interval, by the way). We’ll cover two sided versions of this

test when we cover P-values.

Exercises

- Which hypothesis is typically assumed to be true in hypothesis testing?

- The null.

- The alternative.

- The type I error rate controls what?

- Load the data set

mtcarsin thedatasetsR package. Assume that the data set mtcars is a random sample. Compute the mean MPG, of this sample. You want

to test whether the true MPG is

of this sample. You want

to test whether the true MPG is  or smaller using a one sided

5% level test. (

or smaller using a one sided

5% level test. ( versus

versus  ).

Using that data set and a Z test:

Based on the mean MPG of the sample

).

Using that data set and a Z test:

Based on the mean MPG of the sample  and by using a Z test: what is the smallest value of

and by using a Z test: what is the smallest value of  that you would reject for (to two decimal places)?

Watch a video solution here

and see the text here.

that you would reject for (to two decimal places)?

Watch a video solution here

and see the text here. - Consider again the

mtcarsdataset. Use a two group t-test to test the hypothesis that the 4 and 6 cyl cars have the same mpg. Use a two sided test with unequal variances. Do you reject? Watch the video here and see the text here - A sample of 100 men yielded an average PSA level of 3.0 with a sd of 1.1. What

are the complete set of values that a 5% two sided Z test of

would fail to reject the null hypothesis for? Watch the video solution and

see the text.

would fail to reject the null hypothesis for? Watch the video solution and

see the text. - You believe the coin that you’re flipping is biased towards heads. You get 55 heads out of 100 flips. Do you reject at the 5% level that the coin is fair? Watch a video solution and see the text.

- Suppose that in an AB test, one advertising scheme led to an average of 10 purchases per day for a sample of 100 days, while the other led to 11 purchases per day, also for a sample of 100 days. Assuming a common standard deviation of 4 purchases per day. Assuming that the groups are independent and that they days are iid, perform a Z test of equivalence. Do you reject at the 5% level? Watch a video solution and see the text.

- A confidence interval for the mean contains:

- All of the values of the hypothesized mean for which we would fail to reject with

.

. - All of the values of the hypothesized mean for which we would fail to reject with

.

. - All of the values of the hypothesized mean for which we would reject with

.

. - All of the values of the hypothesized mean for which we would reject with

.

Watch a video solution and see the text.

.

Watch a video solution and see the text.

- All of the values of the hypothesized mean for which we would fail to reject with

- In a court of law, all things being equal, if via policy you require a lower

standard of evidence to convict people then

- Less guilty people will be convicted.

- More innocent people will be convicted.

- More Innocent people will be not convicted. Watch a video solution and see the text.