7. Asymptopia

Asymptotics

Watch this video before beginning.

Asymptotics is the term for the behavior of statistics as the sample size limits to infinity. Asymptotics are incredibly useful for simple statistical inference and approximations. Asymptotics often make hard problems easy and difficult calculations simple. We will not cover the philosophical considerations in this book, but is true nonetheless, that asymptotics often lead to nice understanding of procedures. In fact, the ideas of asymptotics are so important form the basis for frequency interpretation of probabilities by considering the long run proportion of times an event occurs.

Some things to bear in mind about the seemingly magical nature of asymptotics. There’s no free lunch and unfortunately, asymptotics generally give no assurances about finite sample performance.

Limits of random variables

We’ll only talk about the limiting behavior of one statistic, the sample mean. Fortunately, for the sample mean there’s a set of powerful results. These results allow us to talk about the large sample distribution of sample means of a collection of iid observations.

The first of these results we intuitively already know. It says that the average limits to what its estimating, the population mean. This result is called the Law of Large Numbers. It simply says that if you go to the trouble of collecting an infinite amount of data, you estimate the population mean perfectly. Note there’s sampling assumptions that have to hold for this result to be true. The data have to be iid.

A great example of this comes from coin flipping. Imagine if  is the average of the result of

is the average of the result of  coin flips

(i.e. the sample proportion of heads). The Law of Large Numbers states that

as we flip a coin over and over, it eventually converges to the

true probability of a head.

coin flips

(i.e. the sample proportion of heads). The Law of Large Numbers states that

as we flip a coin over and over, it eventually converges to the

true probability of a head.

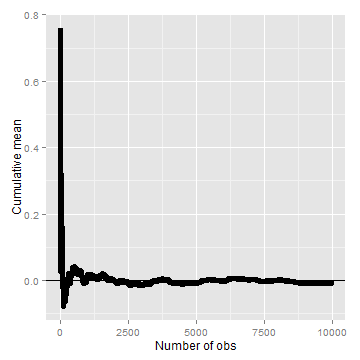

Law of large numbers in action

Let’s try using simulation to investigate the law of large numbers in action. Let’s simulate a lot of standard normals and plot the cumulative means. If the LLN is correct, the line should converge to 0, the mean of the standard normal distribution.

<- 10000

means <- cumsum(rnorm(n))/(1:n)

library(ggplot2)

g <- ggplot(data.frame(x = 1:n, y = means), aes(x = x, y = y))

g <- g + geom_hline(yintercept = 0) + geom_line(size = 2)

g <- g + labs(x = "Number of obs", y = "Cumulative mean")

g

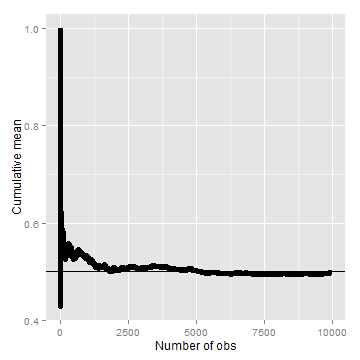

Law of large numbers in action, coin flip

Let’s try the same thing, but for a fair coin flip. We’ll simulate a lot of coin flips and plot the cumulative proportion of heads.

<- cumsum(sample(0:1, n, replace = TRUE))/(1:n)

g <- ggplot(data.frame(x = 1:n, y = means), aes(x = x, y = y))

g <- g + geom_hline(yintercept = 0.5) + geom_line(size = 2)

g <- g + labs(x = "Number of obs", y = "Cumulative mean")

g

Discussion

An estimator is called consistent if it converges to what you want to estimate. Thus, the LLN says that the sample mean of iid sample is consistent for the population mean. Typically, good estimators are consistent; it’s not too much to ask that if we go to the trouble of collecting an infinite amount of data that we get the right answer. The sample variance and the sample standard deviation of iid random variables are consistent as well.

The Central Limit Theorem

Watch this video before beginning.

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) is one of the most important theorems in statistics. For our purposes, the CLT states that the distribution of averages of iid variables becomes that of a standard normal as the sample size increases. Consider this fact for a second. We already know the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of averages from iid samples. The CLT gives us an approximation to the full distribution! Thus, for iid samples, we have a good sense of distribution of the average event though: (1) we only observed one average and (2) we don’t know what the population distribution is. Because of this, the CLT applies in an endless variety of settings and is one of the most important theorems ever discovered.

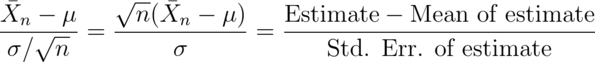

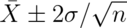

The formal result is that

has a distribution like that of a standard normal for large  .

Replacing the standard error by its estimated value doesn’t change the CLT.

.

Replacing the standard error by its estimated value doesn’t change the CLT.

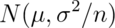

The useful way to think about the CLT is that  is approximately

is approximately  .

.

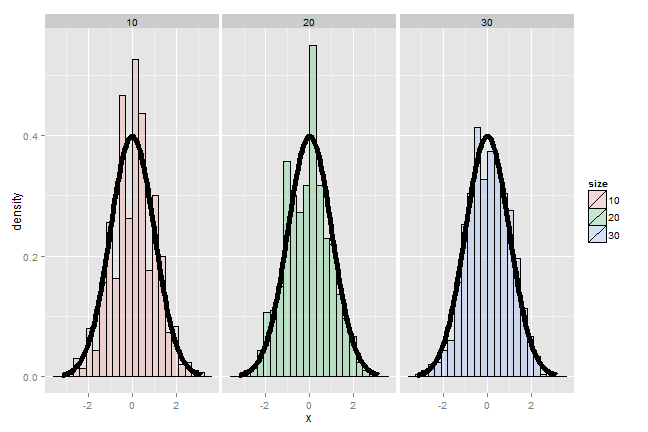

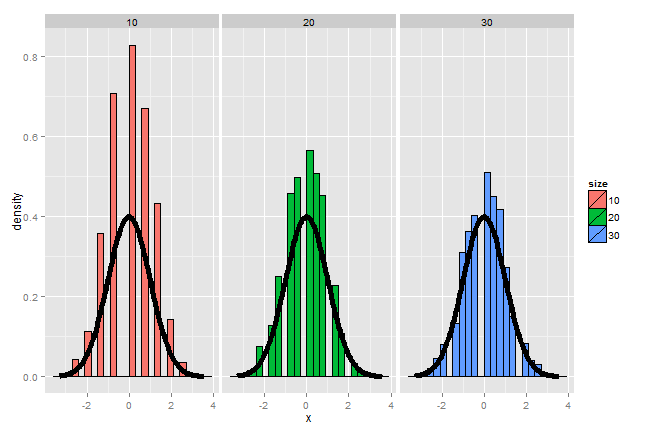

CLT simulation experiments

Let’s try simulating lots of averages from various distributions and showing that the resulting distribution looks like a bell curve.

Die rolling

- Simulate a standard normal random variable by rolling

(six sided) dice.

(six sided) dice. - Let

be the outcome for die

be the outcome for die  .

. - Then note that

![\mu = E[X_i] = 3.5](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_316.png) .

. - Recall also that

.

. - SE

.

. - Lets roll

dice, take their mean, subtract off 3.5,

and divide by

dice, take their mean, subtract off 3.5,

and divide by  and repeat this over and over.

and repeat this over and over.

It’s pretty remarkable that the approximation works so well with so few rolls of the die. So, if you’re stranded on an island, and need to simulate a standard normal without a computer, but you do have a die, you can get a pretty good approximation with 10 rolls even.

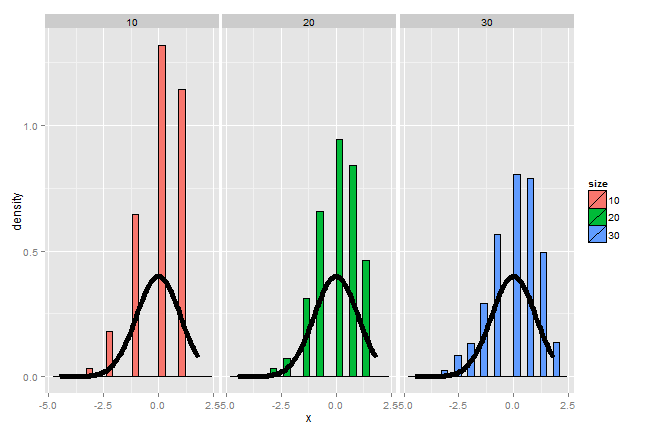

Coin CLT

In fact the oldest application of the CLT is to the idea of flipping coins

(by de Moivre).

Let  be the 0 or 1 result of the

be the 0 or 1 result of the  flip of a possibly

unfair coin. The sample proportion, say

flip of a possibly

unfair coin. The sample proportion, say  , is the average of the

coin flips. We know that:

, is the average of the

coin flips. We know that:

-

![E[X_i] = p](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_324.png) ,

, -

,

, -

.

.

Furthermore, because of the CLT, we also know that:

will be approximately normally distributed.

Let’s test this by flipping a coin  times, taking the sample proportion

of heads, subtract off 0.5 and multiply the result by

times, taking the sample proportion

of heads, subtract off 0.5 and multiply the result by

(divide by

(divide by  ).

).

This convergence doesn’t look quite as good as the die, since the coin has

fewer possible outcomes. In fact, among coins of various degrees of bias,

the convergence to normality is governed by how far from 0.5  is.

Let’s redo the simulation, now using

is.

Let’s redo the simulation, now using  instead of

instead of  like we did before.

like we did before.

Notice that the convergence to normality is quite poor. Thus, be careful when using CLT approximations for sample proportions when your proportion is very close to 0 or 1.

Confidence intervals

Watch this video before beginning.

Confidence intervals are methods for quantifying uncertainty in our estimates. The fact that the interval has width characterizes that there is randomness that prevents us from getting a perfect estimate. Let’s go through how a confidence interval using the CLT is constructed.

According to the CLT, the sample mean,  ,

is approximately normal with mean

,

is approximately normal with mean  and standard

deviation

and standard

deviation  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,

is pretty far out in the tail (only 2.5% of a normal being larger than 2 sds in the tail). Similarly,

is pretty far in the left tail (only 2.5% chance of a normal being smaller than

2 standard deviations in the tail). So the probability

is bigger than

is bigger than  or smaller than

or smaller than  is 5%.

Or equivalently, the probability that these limits contain

is 5%.

Or equivalently, the probability that these limits contain  is 95%. The quantity:

is 95%. The quantity:

is called a 95% interval for  .

The 95% refers to the fact that if one were to repeatedly

get samples of size

.

The 95% refers to the fact that if one were to repeatedly

get samples of size  , about 95% of the intervals obtained

would contain

, about 95% of the intervals obtained

would contain  . The 97.5th quantile is 1.96 (so I rounded to 2 above).

If instead of a 95% interval, you wanted a 90% interval, then

you want (100 - 90) / 2 = 5% in each tail. Thus your replace the 2 with

the 95th percentile, which is 1.645.

. The 97.5th quantile is 1.96 (so I rounded to 2 above).

If instead of a 95% interval, you wanted a 90% interval, then

you want (100 - 90) / 2 = 5% in each tail. Thus your replace the 2 with

the 95th percentile, which is 1.645.

Example CI

Give a confidence interval for the average height of sons in Galton’s data.

> library(UsingR)

> data(father.son)

> x <- father.son$sheight

> (mean(x) + c(-1, 1) * qnorm(0.975) * sd(x)/sqrt(length(x)))/12

[1] 5.710 5.738

Here we divided by 12 to get our interval in feet instead of inches. So we estimate the average height of the sons as 5.71 to 5.74 with 95% confidence.

Example using sample proportions

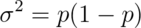

In the event that each  is 0 or 1

with common success probability

is 0 or 1

with common success probability  then

then  .

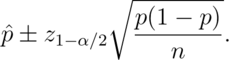

The interval takes the form:

.

The interval takes the form:

Replacing  by

by  in the standard error results in what

is called a Wald confidence interval for

in the standard error results in what

is called a Wald confidence interval for  . Remember also that

. Remember also that

is maximized at 1/4. Plugging this in and setting

our

is maximized at 1/4. Plugging this in and setting

our  quantile as 2 (which is about a 95% interval) we find

that a quick and dirty confidence interval is:

quantile as 2 (which is about a 95% interval) we find

that a quick and dirty confidence interval is:

This is useful for doing quick confidence intervals for binomial proportions in your head.

Example

Your campaign advisor told you that in a random sample of 100 likely voters, 56 intent to vote for you. Can you relax? Do you have this race in the bag? Without access to a computer or calculator, how precise is this estimate?

> 1/sqrt(100)

[1] 0.1

so a back of the envelope calculation gives an approximate 95% interval

of (0.46, 0.66).

Thus, since the interval contains 0.5 and numbers below it, there’s not enough votes for you to relax; better go do more campaigning!

The basic rule of thumb is then,  gives you a

good estimate for the margin of error of a proportion. Thus,

gives you a

good estimate for the margin of error of a proportion. Thus,

for about 1 decimal place, 10,000 for 2, 1,000,000 for 3.

> round(1/sqrt(10^(1:6)), 3)

[1] 0.316 0.100 0.032 0.010 0.003 0.001

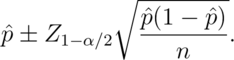

We could very easily do the full Wald interval, which is less conservative (may provide a narrower interval). Remember the Wald interval for a binomial proportion is:

Here’s the R code for our election setting, both coding it directly

and using binom.test.

> 0.56 + c(-1, 1) * qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(0.56 * 0.44/100)

[1] 0.4627 0.6573

> binom.test(56, 100)$conf.int

[1] 0.4572 0.6592

Simulation of confidence intervals

It is interesting to note that the coverage of confidence intervals describes an aggregate behavior. In other words the confidence interval describes the percentage of intervals that would cover the parameter being estimated if we were to repeat the experiment over and over. So, one can not technically say that the interval contains the parameter with probability 95%, say. So called Bayesian credible intervals address this issue at the expense (or benefit depending on who you ask) of adopting a Bayesian framework.

For our purposes, we’re using confidence intervals and so will investigate

their frequency performance over repeated realizations of the experiment.

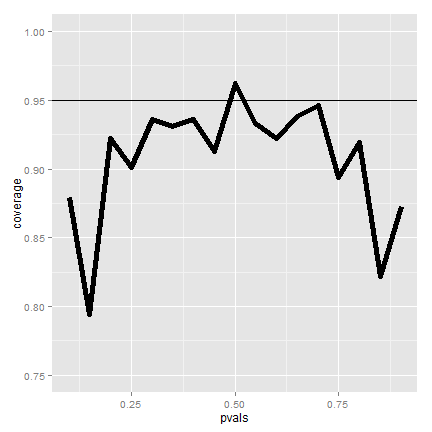

We can do this via simulation. Let’s consider different values of

and look at the Wald interval’s coverage when we repeatedly

create confidence intervals.

and look at the Wald interval’s coverage when we repeatedly

create confidence intervals.

<- 20

pvals <- seq(0.1, 0.9, by = 0.05)

nosim <- 1000

coverage <- sapply(pvals, function(p) {

phats <- rbinom(nosim, prob = p, size = n)/n

ll <- phats - qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

ul <- phats + qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

mean(ll < p & ul > p)

})

The figure shows that if we were to repeatedly try experiments for

any fixed value of  , it’s rarely the case that our intervals

will cover the value that they’re trying to estimate in 95% of them.

This is bad, since covering the parameter that its estimating 95% of the

time is the confidence interval’s only job!

, it’s rarely the case that our intervals

will cover the value that they’re trying to estimate in 95% of them.

This is bad, since covering the parameter that its estimating 95% of the

time is the confidence interval’s only job!

So what’s happening? Recall that the CLT is an approximation. In this case

isn’t large enough for the CLT to be applicable

for many of the values of

isn’t large enough for the CLT to be applicable

for many of the values of  . Let’s see if the coverage improves

for larger

. Let’s see if the coverage improves

for larger  .

.

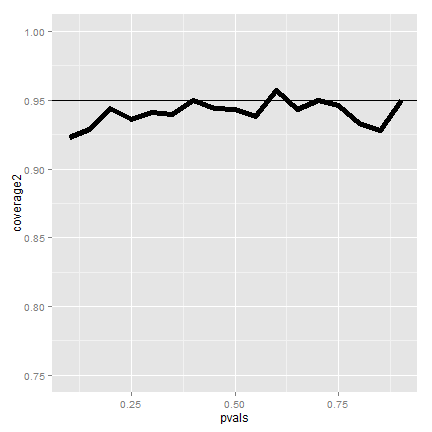

<- 100

pvals <- seq(0.1, 0.9, by = 0.05)

nosim <- 1000

coverage2 <- sapply(pvals, function(p) {

phats <- rbinom(nosim, prob = p, size = n)/n

ll <- phats - qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

ul <- phats + qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

mean(ll < p & ul > p)

})

.

.Now it looks much better. Of course, increasing our sample size is rarely an option. There’s exact fixes to make this interval work better for small sample sizes.

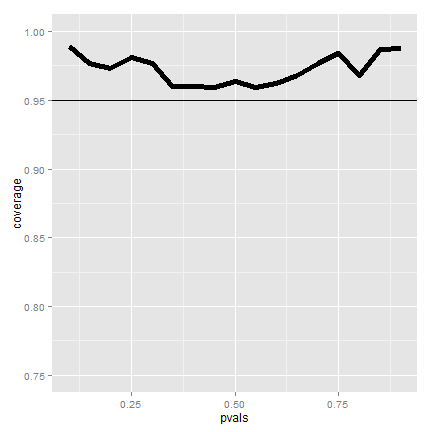

However, for a quick fix is to take your data and add two successes and two failures. So, for example, in our election example, we would form our interval with 58 votes out of 104 sampled (disregarding that the actual numbers were 56 and 100). This interval is called the Agresti/Coull interval. This interval has much better coverage. Let’s show it via a simulation.

<- 20

pvals <- seq(0.1, 0.9, by = 0.05)

nosim <- 1000

coverage <- sapply(pvals, function(p) {

phats <- (rbinom(nosim, prob = p, size = n) + 2)/(n + 4)

ll <- phats - qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

ul <- phats + qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(phats * (1 - phats)/n)

mean(ll < p & ul > p)

})

The coverage is better, if maybe a little conservative in the sense of being

over the 95% line most of the time. If the interval is too conservative, it’s

likely a little too wide. To see this clearly, imagine if we made our interval

to

to  . Then we would always have 100% coverage

in any setting, but the interval wouldn’t be useful. Nonetheless, the Agrestic/Coull

interval gives a much better trade off between coverage and width than the Wald

interval.

. Then we would always have 100% coverage

in any setting, but the interval wouldn’t be useful. Nonetheless, the Agrestic/Coull

interval gives a much better trade off between coverage and width than the Wald

interval.

In general, one should use the add two successes and failures method for binomial

confidence intervals with smaller  . For very small

. For very small  consider

using an exact interval (not covered in this class).

consider

using an exact interval (not covered in this class).

Poisson interval

Since the Poisson distribution is so central for data science, let’s

do a Poisson confidence interval. Remember that if

then our estimate of

then our estimate of  is

is  .

Furthermore, we know that

.

Furthermore, we know that

and so the natural estimate

is

and so the natural estimate

is  . While it’s not immediate

how the CLT applies in this case, the interval is of the familiar form

. While it’s not immediate

how the CLT applies in this case, the interval is of the familiar form

So our Poisson interval is:

Example

A nuclear pump failed 5 times out of 94.32 days. Give a 95% confidence interval for the failure rate per day.

> x <- 5

> t <- 94.32

> lambda <- x/t

> round(lambda + c(-1, 1) * qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(lambda/t), 3)

[1] 0.007 0.099

A non-asymptotic test, one that guarantees coverage, is also available. But, it has to be evaluated numerically.

> poisson.test(x, T = 94.32)$conf

[1] 0.01721 0.12371

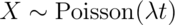

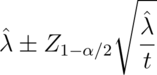

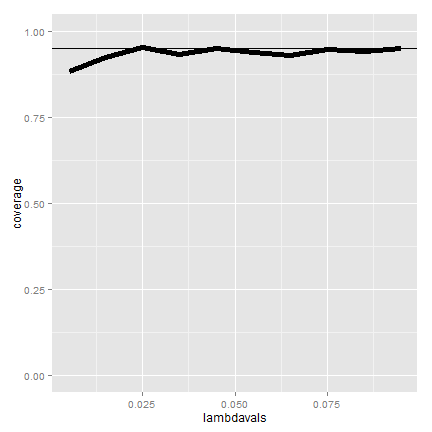

Simulating the Poisson coverage rate

Let’s see how the asymptotic interval performs for lambda values near what we’re estimating.

<- seq(0.005, 0.1, by = 0.01)

nosim <- 1000

t <- 100

coverage <- sapply(lambdavals, function(lambda) {

lhats <- rpois(nosim, lambda = lambda * t)/t

ll <- lhats - qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(lhats/t)

ul <- lhats + qnorm(0.975) * sqrt(lhats/t)

mean(ll < lambda & ul > lambda)

})

The coverage can be low for low values of lambda. In this case the asymptotics

works as we increase the monitoring time, t. Here’s the coverage if we

increase  to 1,000.

to 1,000.

Summary notes

- The LLN states that averages of iid samples. converge to the population means that they are estimating.

- The CLT states that averages are approximately normal, with

distributions.

- centered at the population mean.

- with standard deviation equal to the standard error of the mean.

- CLT gives no guarantee that $n$ is large enough.

- Taking the mean and adding and subtracting the relevant.

normal quantile times the SE yields a confidence interval for the mean.

- Adding and subtracting 2 SEs works for 95% intervals.

- Confidence intervals get wider as the coverage increases.

- Confidence intervals get narrower with less variability or larger sample sizes.

- The Poisson and binomial case have exact intervals that

don’t require the CLT.

- But a quick fix for small sample size binomial calculations is to add 2 successes and failures.

Exercises

- I simulate 1,000,000 standard normals. The LLN says that their sample average must be close to?

- About what is the probability of getting 45 or fewer heads out 100 flips of a fair coin? (Use the CLT, not the exact binomial calculation).

- Consider the father.son data. Using the CLT and assuming that the fathers are a random sample from a population of interest, what is a 95% confidence mean height in inches?

- The goal of a a confidence interval having coverage 95% is to imply that:

- If one were to repeated collect samples and reconstruct the intervals, around 95% percent of them would contain the true mean being estimated.

- The probability that the sample mean is in the interval is 95%.

- The rate of search entries into a web site was 10 per minute when monitoring for an hour. Use R to calculate the exact Poisson interval for the rate of events per minute?

- Consider a uniform distribution. If we were to sample 100 draws from a

a uniform distribution (which has mean 0.5, and variance 1/12) and take their

mean,

.

What is the approximate probability of getting as large as 0.51 or larger?

Watch this video solution and see the problem and solution here..

.

What is the approximate probability of getting as large as 0.51 or larger?

Watch this video solution and see the problem and solution here..