3. Conditional probability

Conditional probability, motivation

Watch this video before beginning.

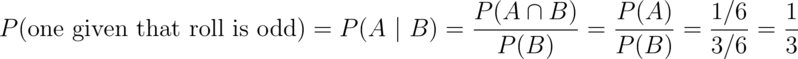

Conditioning is a central subject in statistics. If we are given information about a random variable, it changes the probabilities associated with it. For example, the probability of getting a one when rolling a (standard) die is usually assumed to be one sixth. If you were given the extra information that the die roll was an odd number (hence 1, 3 or 5) then conditional on this new information, the probability of a one is now one third.

This is the idea of conditioning, taking away the randomness that we know to have occurred. Consider another example, such as the result of a diagnostic imaging test for lung cancer. What’s the probability that a person has cancer given a positive test? How does that probability change under the knowledge that a patient has been a lifetime heavy smoker and both of their parents had lung cancer? Conditional on this new information, the probability has increased dramatically.

Conditional probability, definition

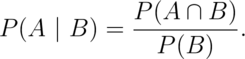

We can formalize the definition of conditional probability so that the mathematics matches our intuition.

Let  be an event so that

be an event so that  .

Then the conditional probability of an event

.

Then the conditional probability of an event  given

that

given

that  has occurred is:

has occurred is:

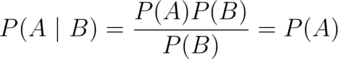

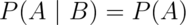

If  and

and  are unrelated in any way, or in other words

independent, (discussed more later in the lecture), then

are unrelated in any way, or in other words

independent, (discussed more later in the lecture), then

That is, if the occurrence of  offers no information about the

occurrence of

offers no information about the

occurrence of  - the probability conditional on the information

is the same as the probability without the information, we say that the

two events are independent.

- the probability conditional on the information

is the same as the probability without the information, we say that the

two events are independent.

Example

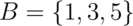

Consider our die roll example again. Here we have that

and

and

Which exactly mirrors our intuition.

Bayes’ rule

Watch this video before beginning

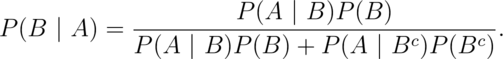

Bayes’ rule is a famous result in statistics and probability. It forms the foundation for large branches of statistical thinking. Bayes’ rule allows us to reverse the conditioning set provided that we know some marginal probabilities.

Why is this useful? Consider our lung cancer example again. It would be relatively easy for physicians to calculate the probability that the diagnostic method is positive for people with lung cancer and negative for people without. They could take several people who are already known to have the disease and apply the test and conversely take people known not to have the disease. However, for the collection of people with a positive test result, the reverse probability is more of interest, “given a positive test what is the probability of having the disease?”, and “given a given a negative test what is the probability of not having the disease?”.

Bayes’ rule allows us to switch the conditioning event, provided a little bit of extra information. Formally Bayes’ rule is:

Diagnostic tests

Since diagnostic tests are a really good example of Bayes’ rule in practice, let’s go over them in greater detail. (In addition, understanding Bayes’ rule will be helpful for your own ability to understand medical tests that you see in your daily life). We require a few definitions first.

Let  and

and  be the events that the result of a

diagnostic test is positive or negative respectively

Let

be the events that the result of a

diagnostic test is positive or negative respectively

Let  and

and  be the event that the subject of the

test has or does not have the disease respectively

be the event that the subject of the

test has or does not have the disease respectively

The sensitivity is the probability that the test is positive given

that the subject actually has the disease,

The specificity is the probability that the test is negative given that

the subject does not have the disease,

So, conceptually at least, the sensitivity and specificity are straightforward to estimate. Take people known to have and not have the disease and apply the diagnostic test to them. However, the reality of estimating these quantities is quite challenging. For example, are the people known to have the disease in its later stages, while the diagnostic will be used on people in the early stages where it’s harder to detect? Let’s put these subtleties to the side and assume that they are known well.

The quantities that we’d like to know are the predictive values.

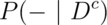

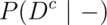

The positive predictive value is the probability that the subject has the disease given that the test is positive,

The negative predictive value is the probability that the subject does not have the disease given that the test is negative,

Finally, we need one last thing, the prevalence of the disease -

which is the marginal probability of disease,  . Let’s now

try to figure out a PPV in a specific setting.

. Let’s now

try to figure out a PPV in a specific setting.

Example

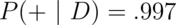

A study comparing the efficacy of HIV tests, reports on an experiment which concluded that HIV antibody tests have a sensitivity of 99.7% and a specificity of 98.5% Suppose that a subject, from a population with a .1% prevalence of HIV, receives a positive test result. What is the positive predictive value?

Mathematically, we want  given the sensitivity,

given the sensitivity,  ,

the specificity,

,

the specificity,  and the prevalence

and the prevalence

.

.

In this population a positive test result only suggests a 6% probability that the subject has the disease, (the positive predictive value is 6% for this test). If you were wondering how it could be so low for this test, the low positive predictive value is due to low prevalence of disease and the somewhat modest specificity

Suppose it was known that the subject was an intravenous drug user and routinely had intercourse with an HIV infected partner? Our prevalence would change dramatically, thus increasing the PPV. You might wonder if there’s a way to summarize the evidence without appealing to an often unknowable prevalence? Diagnostic likelihood ratios provide this for us.

Diagnostic Likelihood Ratios

The diagnostic likelihood ratios summarize the evidence of disease given a positive or negative test. They are defined as:

The diagnostic likelihood ratio of a positive test, labeled  ,

is

,

is  , which is the

, which is the

.

.

The diagnostic likelihood ratio of a negative test, labeled  ,

is

,

is  , which is the

, which is the

.

.

How do we interpret the DLRs? This is easiest when looking at so called

odds ratios. Remember that if  is a probability, then

is a probability, then

is the odds. Consider now the odds in our setting:

is the odds. Consider now the odds in our setting:

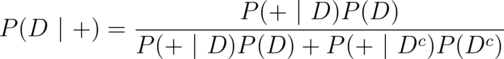

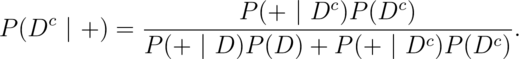

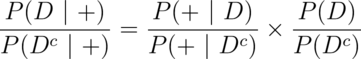

Using Bayes rule, we have

and

Therefore, dividing these two equations we have:

In other words, the post test odds of disease is the pretest odds of disease

times the  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  relates the decrease in the odds

of the disease after a negative test result to the odds of disease prior to

the test.

relates the decrease in the odds

of the disease after a negative test result to the odds of disease prior to

the test.

So, the DLRs are the factors by which you multiply your pretest odds to get

your post test odds. Thus, if a test has a  of 6, regardless

of the prevalence of disease, the post test odds is six times that of the

pretest odds.

of 6, regardless

of the prevalence of disease, the post test odds is six times that of the

pretest odds.

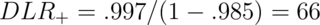

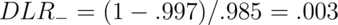

HIV example revisited

Let’s reconsider our HIV antibody test again.

Suppose a subject has a positive HIV test

The result of the positive test is that the odds of disease is now 66 times the pretest odds. Or, equivalently, the hypothesis of disease is 66 times more supported by the data than the hypothesis of no disease

Suppose instead that a subject has a negative test result

Therefore, the post-test odds of disease is now 0.3% of the pretest odds given

the negative test. Or, the hypothesis of disease is supported  times that of the hypothesis of absence of disease given the negative test result

times that of the hypothesis of absence of disease given the negative test result

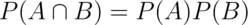

Independence

Watch this video before beginning.

Statistical independence of events is the idea that the events are unrelated. Consider successive coin flips. Knowledge of the result of the first coin flip tells us nothing about the second. We can formalize this into a definition.

Two events  and

and  are independent if

are independent if

Equivalently if  . Note that since

. Note that since  is

independent of

is

independent of  we know that

we know that  is independent of

is independent of

is independent of

is independent of

is independent of

is independent of  .

.

While this definition works for sets, remember that random variables are really the things

that we are interested in. Two random variables,  and

and  are independent

if for any two sets

are independent

if for any two sets

and

and

![P([X \in A] \cap [Y \in B]) = P(X\in A)P(Y\in B)](/preview_site_images/LittleInferenceBook/leanpub_equation_117.png)

We will almost never work with these definitions. Instead, the important principle is that probabilities of independent things multiply! This has numerous consequences, including the idea that we shouldn’t multiply non-independent probabilities.

Example

Let’s cover a very simple example:

“What is the probability of getting two consecutive heads?”. Then we have

that  is the event of getting a head on flip 1

is the event of getting a head on flip 1

is the event of getting a head on flip 2

is the event of getting a head on flip 2

is the event of getting heads on flips 1 and 2. Then

independence would tell us that:

is the event of getting heads on flips 1 and 2. Then

independence would tell us that:

This is exactly what we would have intuited of course. But, it’s nice that the mathematics mirrors our intuition. In more complex settings, it’s easy to get tripped up. Consider the following famous (among statisticians at least) case study.

Case Study

Volume 309 of Science reports on a physician who was on trial for expert

testimony in a criminal trial. Based on an estimated prevalence of sudden

infant death syndrome (SIDS) of 1 out of 8,543, a physician testified that that

the probability of a mother having two children with SIDS was

. The mother on trial was convicted

of murder.

. The mother on trial was convicted

of murder.

Relevant to this discussion, the principal mistake was to assume that the

events of having SIDs within a family are independent. That is,

is not necessarily equal to

is not necessarily equal to  .

This is because biological processes that have a believed genetic or familiar

environmental component, of course, tend to be dependent within families.

Thus, we can’t just multiply the probabilities to obtain the result.

.

This is because biological processes that have a believed genetic or familiar

environmental component, of course, tend to be dependent within families.

Thus, we can’t just multiply the probabilities to obtain the result.

There are many other interesting aspects to the case. For example, the idea of a low probability of an event representing evidence against a plaintiff. (Could we convict all lottery winners of fixing the lotter since the chance that they would win is so small.)

IID random variables

Now that we’ve introduced random variables and independence, we can introduce a central modeling assumption made in statistics. Specifically the idea of a random sample. Random variables are said to be independent and identically distributed (iid) if they are independent and all are drawn from the same population. The reason iid samples are so important is that they are a model for random samples. This is a default starting point for most statistical inferences.

The idea of having a random sample is powerful for a variety of reasons. Consider that in some study designs, such as in election polling, great pains are made to make sure that the sample is randomly drawn from a population of interest. The idea is to expend a lot of effort on design to get robust inferences. In these settings assuming that the data is iid is both natural and warranted.

In other settings, the study design is far more opaque, and statistical inferences are conducted under the assumption that the data arose from a random sample, since it serves as a useful benchmark. Most studies in the fields of epidemiology and economics fall under this category. Take, for example, studying how policies impact countries gross domestic product by looking at countries before and after enacting the policies. The countries are not a random sample from the set of countries. Instead, conclusions must be made under the assumption that the countries are a random sample and the interpretation of the strength of the inferences adapted in kind.

Exercises

- I pull a card from a deck and do not show you the result. I say that the resulting card is a heart. What is the probability that it is the queen of hearts?

- The odds associated with a probability,

, are defined as?

, are defined as? - The probability of getting two sixes when rolling a pair of dice is?

- The probability that a manuscript gets accepted to a journal is 12% (say). However, given that a revision is asked for, the probability that it gets accepted is 90%. Is it possible that the probability that a manuscript has a revision asked for is 20%? Watch a video of this problem getting solved and see the worked out solutions here.

- Suppose 5% of housing projects have issues with asbestos. The sensitivity of a test for asbestos is 93% and the specificity is 88%. What is the probability that a housing project has no asbestos given a negative test expressed as a percentage to the nearest percentage point? Watch a video solution here and see the worked out problem here.