Chapter Two: Raising a Biliterate Child in Japan: A Case Study of a Bicultural Family

Sanborn Brown

Osaka Kyoiku University, Japan

Sae Matsuda

Setsunan University, Japan

Abstract

This paper reports on a case study of a bicultural family in Japan. Krashen (2004:61) claims “Often, those who ‘hate to read’ simply do not have access to books.” The bicultural family in this study tried to make sure of the opposite and provide books for their child. A Japanese/American child, who obtained sufficient input during her early developmental phase, has learned to read autonomously and achieved a highly proficient level of English. Several factors that have presumably contributed to her literacy will be discussed.

Introduction

Although Smith (1994) and others have reported some successful case studies, for a native speaker of Japanese living and attending school in Japan, becoming bilingual is no easy feat. The survey results reported by Noguchi (1996a) reveal that the two language management strategies (“one parent-one language” strategy and home/community language strategy) “often face a wide range of problems, especially after the children reach school age and when families have more than one child” (p.245).

Therefore, becoming biliterate in English (and Japanese) is no doubt even more daunting. As Noguchi (1996b) argues, learning to read in one’s native language while living in one’s native country is hard enough; to attempt to learn a language as different as English is from Japanese is all the more so. The written and grammatical systems have nothing in common. With the exception of loan words, the spoken language is totally different as well.

Why bother with adding a second, unrelated language when school, community, and in many cases home life are conducted in Japanese? The obvious answers would include future professional opportunities, being able to communicate with relatives and non-Japanese speakers, using email, a feeling of affinity with a parent’s native written language, etc. Beyond these personal reasons, research has shown that multiple advantages accrue to those who attain a high level of literacy in two languages: creativity and divergent thinking (Baker, Rudd, & Pomeroy, 2001), metalinguistic awareness (Bialystok, Luk, & Kwan, 2005), cognitive flexibility (Hakuta & Dias, 1985), intercultural communicative competence (Lüdi, 2006), and enriched linguistic repertoire (Pavelenko, 2009).

Once one has decided to go down the path of biliteracy, the issue of how to proceed arises.

The Case Study

Participant

The participant of this case study is Mona Matsuda. She was born in Kyoto, Japan, in 1998, and is currently 17-years-old. Her father is an American national who has lived in Japan for more than two decades. Her mother is a Japanese national who spent two years in the United States.

Mona’s dominant language is Japanese (or, more specifically, Kyoto dialect), her second language English. She has spent her entire life in Kyoto, and attended local day care centers and public neighborhood elementary and junior high schools. She is now a second year high school student at a public school in Kyoto.

Language & Culture Environments

From the time of her birth, Mona was immersed in an unusual home language environment. For the first 5-6 years of her life, her parents alternated languages by day. For example, if on Monday they spoke in English, Tuesday would be a “Japanese” day. In recent years, however, Japanese has become the dominant language of the family.

Still, within the family, the parents have roughly maintained for 17 years a “one parent-one language” policy. That is, the father – with some exceptions (e.g., in a situation in which mono-lingual Japanese are present) – only speaks in English to Mona. Similarly, the mother only speaks in Japanese to Mona. Outside of the home, Mona’s linguistic environment is overwhelmingly Japanese.

Both parents’ knowledge of the two languages helped communication because Mona, in the first years of her life, responded only in Japanese to Father’s questions in English; this did not, however, cause a communication breakdown. After Mona started speaking English with her father, Mother participated in Japanese, or Father sometimes joined in (in whichever language) when Mona and Mother were talking in Japanese. In other words, when it comes to a family conversation, the language spoken was flexible and depended on the situation: all Japanese, two people speaking English/one speaking Japanese, or two speaking Japanese/one speaking English.

Mona was fortunate to have cultural input at an early age as well. Her household celebrated events from both cultures. She enjoyed the traditional Japanese feast on New Year’s day and threw beans to drive off evil spirits at Setsubun; similarly, she went egg hunting on Easter and trick-or-treading on Halloween. She also visited her American family and relatives once or twice a year.

Bedtime Reading and More

From a very young age, both parents read to Mona every night. The nightly reading selection was left to Mona, who sometimes chose English books for her mother and, conversely, Japanese books for her father to read. (In this event, her father would often read in Japanese and then summarize the story in English.)

In addition to the above routine, the parents provided additional access to books with frequent visits to local libraries and bookstores. Whenever and wherever they traveled, finding a good bookstore was at the top of things to do. They read on the train and the plane.

Her grandparents were also generous providers of books for her. Especially her Japanese grandfather, also a book lover, enjoyed taking her to bookstores and buying several books every time they went. He even gave her book coupons after he won in Go (an Asian board game) tournaments.

Mona liked Japanese folktales as well as Dr. Suess’s ABC. She enjoyed demons and monks while she was fascinated by princesses and fairies. Her favorite books at an early stage included The Very Hungry Caterpillar (by Eric Carle), Good Night Moon (by Margaret Wise Brown), The Going to Bed Book & Moo, Baa, La La La! (by Susan Boynton), and In a Dark Dark Room and Other Scary Stories (by Alvin Schwartz).

As she grew older, the effects of the “one parent-one language” system became more apparent. At bedtime her father read English books such as Harry Potter, and her mother read translated versions of Astrid Lindgren books in Japanese. Her mother had enjoyed reading these 40 year-old books when she was young. The end of the Harry Potter series coincided with the time in which the parents faded out of bedtime reading.

Other English Input

Other English input included videos and television programs, primarily from the United States. She started with Sesame Street and PBS kids programs and moved on to the Disney Channel. Another bilingual family gave her Barney home videos, which she enjoyed for a while. Her favorite videos, however, included The Wizard of Oz, The Sound of Music, and the Indiana Jones series. She often asked her parents to tell those stories at bedtime as well. She watched most of the Disney movies on video while she saw the latest animated movie at a movie theater. (This sometimes meant waiting for a night showing so that they could watch it in English with Japanese subtitles. Many films for children are, not surprisingly, dubbed.)

Sunday Study Group: Completely Bilingual

The second prong of attaining biliteracy was a “Sunday School” called Completely Bilingual. As Nobuoka, Isozaki, and Miyake (2015) pointed out, having “a group of their peers” is key. Completely Bilingual was a great boost to Mona’s language development. This was a group founded by three international couples in Kyoto. The group rented space at a Woman’s Center in the city, hired teachers, bought educational materials from the United States, and met every Sunday for one hour during the school year. The classes were set roughly based upon school grade level. Mona attended from approximately age four until the end of elementary school, at age 12, at which point the students “graduate” from the program.

Here Mona learned phonics, spelling, and reading. The students completed short homework assignments every week. By the time she had finished the program, she was for all intents and purposes an independent reader – in both Japanese and English.

Scholastic Book Club

A mother in Completely Bilingual group was a member of the Scholastic Book Club (currently called Scholastic Reading Club). Other families took advantage of this access and placed monthly orders for their children to encourage extensive reading outside of class. Mona received four catalogs (SeeSaw for Grades K-1, Lucky for Grades 2-3, and Arrow for Grades 4-6, TAB for Grades 7 and up) every month and happily circled the books she would like to read. Her mother examined what Mona had marked and ordered most of the selected items although some censorship came into play. When the books arrived, Mona buried her nose in books for hours and read one after another and another until she finished most or all of them.

Extensive Reading in Japanese

Mona’s elementary school also encouraged reading. Every morning children had a “morning reading time” for 10-15 minutes. Students chose a book from the class library or read a book they brought. They were given a reading record booklet to note the books they had read. When they reached 100 books, students went to the principal’s office and received a certificate and a paper medal. This way, Mona kept reading in both English and Japanese. As Cummins (1991) noted, there is an “interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children” – which was apparent in Mona.

Extensive Reading Marathon

When her mother initiated extensive reading at her university, she encouraged Mona to join. Mona started keeping reading records when she was 7. Although she had learned to spell English words by then, she needed help writing necessary information at first. Eventually she became autonomous and kept records quite diligently for the next 4 years. By the time she turned 11, however, she grew tired of recording the books she read, and she stopped keeping track. Although her reading records may not be totally accurate or consistent, it is worthwhile to see how she has developed her English literacy by analyzing her reading records.

Data Analysis

Table 1 shows the total word count, the number of books, and the average length of books that Mona read each year from 2nd grade to 5th grade.

Table 1: Books Read by Grade

| Grade(Age) | 2nd(7-8) | 3rd(8-9) | 4th(9-10) | 5th(10-11) |

| Total Word Count | 1,843,075 | 1,798,009 | 3,538,427 | 2,811,838 |

| Number of Books | 142 | 66 | 91 | 74 |

| Average | 13,356 | 27,243 | 38,884 | 37,998 |

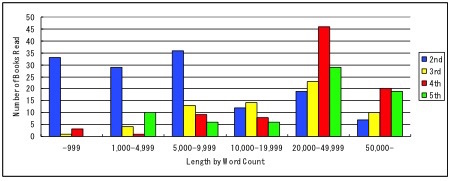

Figure 1 indicates the number of books she read by the length. When she was in 2nd grade, most of the books she read were less than 10,000 words, but when she was in 4th grade, the majority of the books she read fell into the “20,000-49,999” category.

Grade 2

The most read series was Oxford Reading Tree (27 titles), followed by Magic Tree House (15 titles). She also read the whole set of A Series of Unfortunate Events. Other series included I Can Read, Geronimo Stilton, Captain under Pants, Oxford Bookworms (Levels 2-3), Penguin Readers (Levels 2-3), My Father’s Dragon series, Nancy Drew, and Scholastic Reader (Level 3). She also started reading The Little House on the Prairie series. In addition to series, she read Flat Stanley, Dear Dumb Diary, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Number the Stars, and The Diary of a Young Girl.

Grade 3

Mona became infatuated with Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys at this stage and read 12 volumes in total. She also read 8 Princess Diary books. Others were Hannah Montana (4), English Roses (4), Charm Club (4), Rainbow Magic (3), In Their Own Words (3), The Dark Materials (2), How I Survived Middle School (2), and Magic Tree House (2). In the previous year she discovered non-fiction reading Anne Frank’s diary, and she continued to read serious themes this year such as Witness (a story of racial discrimination perpetrated by the KKK), Four Perfect Pebbles (the Holocaust), and Code Talker (about American Indians during WWII) in addition to a variety of other books such as The Cupid Chronicles, Chasing Vermeer, Time Cat, Bad Bad Darlings, and Montmorency and the Assassins. Mona discovered Meg Cabot here.

Grade 4

Mona read A Series of Unfortunate Events for the second time and several new series such as Candy Apple (11), Emily Windsnap (5), Rainbow Magic (4), The Uglies (3), Dear Dumb Diary (3), Eddie Dickens Trilogy (2), Melanie Martin (2), Twilight Saga (2), and Kiki Strike (2). Other titles included Eggs, Bound, Fairest, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, The Tales of Beedle the Bard, Pollyanna, Corby Flood, The Mysterious Benedict Society, Before Midnight: A Retelling of “Cinderella,” and Airhead. She started reading not only Meg Cabot but also Stephenie Meyer. Apparently she had entered an adolescent female stage here.

Grade 5

She reread the full set of A Series of Unfortunate Events for the third time. Other series she read were: I Can Read (9), Sisters Grimm (5), The Gemma Doyle Trilogy (3), The Clique (3), Geronimo Stilton (2), The Book of Time (2), Little Darlings (2), and Flat Stanley (2). She also read The Book Thief, Stuart Little, The Legend of Spud Murphy, Princess Protection Program, The Secret School, Green Angel, Shakespeare’s Secret, My Life in Pink & Green, Ways to Live Forever, Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, The Cupcake Queen, and The Sweet Far Thing. She enjoyed a variety of themes both funny and serious and read a lot of adolescent female novels as well.

Thus, she simply kept reading and reading. How far did she get?

English Proficiency

Her “formal” English education began when she entered public junior high school. In a sense, she “re-learned” the alphabet in the Japanese way; however, it became obvious that she had learned more from books than she would from public school English education. The school encouraged students to take an English proficiency test called EIKEN, and Mona agreed to do so. She passed Grade 2 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 500-640; TOEFL iBT 56-68) at the age of 13, Grade Pre-1 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 740-840: TOEFL iBT 80-97), and Grade 1 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 900-960; TOEFL iBT 104-110) by the time she graduated from junior high school at the age of 15. She didn’t prepare except for a bit of speech practice before the Grade 1 interview test and made “an educated guess” whenever necessary. Apparently her background knowledge and a wide range of passive vocabulary – acquired from books – made it possible.

Discussion

Smith (1994) has argued for beginning teaching – that is, having children begin learning – in a second language after elementary school has begun. Others, like Noguchi (1996b), say, no, the reality of Japanese elementary school and its homework load demands beginning earlier. Mona started early – before elementary school – and it worked. As Noguchi (1996b) notes, English in Japan is highly valorized. From a very early age, like other bilingual/biliterate children Mona was envied for her proficiency in English. The positive image toward English no doubt motivated her to use the language as well.

The cultural environment Mona enjoyed was a household in which two languages were used freely, in which there were many books and reading materials in both languages, and supportive grandparents. The language used at home was flexible: somewhere between the “one parent-one language” strategy and the home/community language strategy. Mona spoke whichever language she felt like speaking and read in whichever language she felt like reading, or more precisely, in whichever language that was available at that time. Moreover, the parents were flexible in their approach in teaching. At the very beginning, Mona and her father worked through phonics books. In addition, they read aloud (see above). In addition to phonics and decoding, they tried to keep the process as enjoyable and “natural” as possible.

Parents, however, do not always make the most patient or best of teachers. Mona and her father worked together for a year or so from age 3-4, and then to both of their relief they discovered the reading/writing program in Kyoto called Completely Bilingual. Mona enjoyed learning in a classroom setting with other children and started working on her homework more seriously. Having an hour-long weekly class may not have been sufficient linguistically, but it turned out to have another important aspect. Like Mona, most of the children were from bicultural families, and meeting them regularly had a positive effect on Mona’s identity. They often shared cultural events such as egg-hunting on Easter and trick-or-treating on Halloween. The interaction with other children and their families in and outside of class undoubtedly helped enhance Mona’s self-image as a prospective bilingual/billiterate child.

Mona learned to read quite early, yet even after Mona became an autonomous reader, the parents kept reading to her at night and made sure she always had easy access to books. As the reading records show, she gradually raised her reading (difficulty) level. When she was in second grade, she read many books shorter than 1,000 words, but in fourth grade she read much longer books, between 20,000 and 50,000 words. After she became a 5th grader, she grew tired of keeping reading records. However, she continued reading without keeping records. She enjoyed both fiction and non-fiction, and her choices included various categories such as adventure, romance, mystery, history, biography, and humor. As Noguchi (1996b, p. 35) writes:

One of the best ways to ensure that children learn to read English is to introduce them to the joys of reading at an early age. And the simplest way to teach children the joys of reading is to read good books — books that both you and your children enjoy — to them.

Conclusion

Mona now reads at grade level in two languages, Japanese and English. Her stronger language – both spoken and written – is her native Japanese. However, due to her diligence and her parents’ sometimes hit-or-miss efforts, she reads independently and freely for pleasure in both languages. She does not need a dictionary, and she understands word play and cultural allusions. Aside from some prodding to do the Completely Bilingual homework, she never needed to be badgered into reading in English; it was a natural, normal, “fun” thing to do. She is proof that biliteracy is an attainable goal. One does not need to attend an international school or live abroad. With a willing child and parents, it can be accomplished.

References

Baker, M., Rudd, R., & Pomeroy, C. (2001). Tapping into the creative potential of higher education: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 51(1), 161-172.

Bialystok, E., Luk, G., & Kwan, E. (2005). Bilingualism, biliteracy, and learning to read: Interactions among languages and writing systems. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(1), 43-61.

Brown, S. (2001). Raising a miracle child: Part 2. Bilingual Japan, 10(5), 11-13.

Cummins, J. (1991). Interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children. In E. Bialystok (ed.), Language processing in bilingual children (pp. 70 - 89). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giambo, D.A., & Szecsi, T. (2015). Promoting and maintaining bilingualism and biliteracy: Cognitive and biliteracy benefits & strategies for monolingual teachers. The Open Communication Journal, 9, (Suppl 1: M8) 56-60.

Hakuta, K., & Diaz, R.M. (1985). The relationship between degree of bilingualism and cognitive ability: A critical discussion and some new longitudinal data. In K.E. Nelson (ed.), Children’s Language, 5, 319-344.

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited Inc.

Lüdi, G. (2006). Multilingual repertoires and the consequences for linguistic theory. In K. Bührig & J. D. ten Thije (eds.), Beyond misunderstanding-Linguistic analyses of intercultural communication, 13-58.

Matsuda, S. (2001). Raising a miracle child: Part 1. Bilingual Japan, 10(5), 8-10.

Nobuoka, M., Isozaki, A.H., & Miyake, S.B. (2015). Starting your bilingual child on the path to biliteracy. In J. Ward (ed.), Monographs on Bilingualism, 17.

Noguchi, M.G. (1996a). The bilingual parent as model for the bilingual child. Policy Science, 245-261.

Noguchi, M.G. (1996b). Adding biliteracy to bilingualism. Monographs on Bilingualism, 4, 1-48.

Pavlenko, A. (2009). Emotions and Multilingualism. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, C. (1994). Teaching children to read in the second language. Monographs on Bilingualism, 1, 1-28.