Chapter Nine: Making Quizzes for M-Reader and the MoodleReader Quiz Module

Barry E. Keith

Gunma University (Maebashi, Gunma, Japan)

Abstract

The MoodleReader Quiz Module (moodlereader.org) and MReader (mreader.org), are effective tools for tracking student progress in an Extensive Reading program and are being used in hundreds of Extensive Reading programs around the world. The MoodleReader quiz module generates ten questions randomly from a quiz bank of 20-30 items. Generally, quizzes are composed of four main question types: true-false, multiple-choice, who said questions, and an ordering problem, in which quiz-takers put the events of the book into the order that they happened. The questions are weighted according to difficulty and an adjustable score of 60% is considered a passing grade. So, how are these quizzes made? This paper describes how the MoodleReader works and the procedure for making quizzes. Teachers are encouraged to try their hand at making quizzes for easy graded readers. It is hoped that the teachers will be inspired to make quizzes for books in their collections in the future.

Introduction

The MoodleReader [Quiz Module] http://moodlereader.org and [MReader] http://mreader.org, are effective tools for tracking student progress in an Extensive Reading (ER) program and are being used in hundreds of Extensive Reading programs around the world. The MoodleReader quiz module generates ten questions randomly from a quiz bank of 20-30 items. Generally, quizzes are composed of four main question types: true-false, multiple-choice, who said questions, and an ordering problem, in which quiz-takers put the events of the book into the order that they happened. The questions are weighted according to difficulty and an adjustable score of 60% is considered a passing grade. So, how are these quizzes made? This workshop describes how the MoodleReader works and the procedure for making quizzes. Attendees can try their hand at making quizzes for easy graded readers. It is hoped that the presentation will inspire the attendees to make quizzes for books in their collections in the future.

Tracking Extensive Reading for Assessment

Assessment of ER

The case for inclusion of an Extensive Reading (ER) component in second language curricula is becoming stronger (Grabe, 2009; Nation, 1996; Waring, 2009). A growing body of empirical studies leave little doubt as to the effectiveness of ER for language learning. Surveys of the literature on ER in L2 acquisition have been published (Grabe, 2010; Iwahori, 2008; Robb & Kano, 2013). Day and Bamford describe ten characteristics of a successful ER program, among them, “Teachers orient students to the goals of the program, explain the methodology, keep track of what each students reads, and guide students in getting the most out of the program,” (1998, p.8). There is less agreement, however, regarding how ER should be assessed and whether ER should be assessed at all (Day & Bamford, 1998; Prowse, 2002; Krashen, 2004). In an ideal world, reading should be its own reward, but teachers rarely have that luxuruy. In reality, teachers often have little choice whether to assess students’ ER (Brierley et al., 2010; Robb, 2002,2008) and there is even mounting evidence that students want their reading to be assessed (Robb, 2015), but in a simple manner and with rapid feedback (Campbell & Weatherford, 2013; Stoeckel et al., 2012). Success with Moodle quizzes can positively affect students’ motivation (Bieri, 2015).

For curriculum-wide implementation of ER, Robb identifies two main obstacles: the physical and the pedagogical (Robb, 2008). To purchase, store and manage a library large enough for hundreds of students is an enormous undertaking. While no simple solution exists to that problem, the MoodleReader was created to address a second concern: How can teachers be assured that students actually have read the books they claim to have read?

According to the MoodleReader website:

The MoodleReader Module provides quizzes on over 4500 graded readers and books for young readers, so that teachers can have a simple way to assess their students’ work. All quizzes are randomized with a time-limit for their completion which allows students to take the quizzes open-book, even at home, while minimizing the possibility of cheating. (para. 1)

The MoodleReader is installed as an activity on existing Moodle websites. However, not every teacher or institution has Moodle installed on the university servers and teachers often need support from the technical staff of their institution. To address this problem, a more user-friendly version, the [M-Reader] http://mreader.org was developed, and is described as “a completely rewritten version of the “MoodleReader” module. This version, which is supported by the various graded reader publishers, is intended to be easy for administrators, teachers and students to use.” (moodlereader.org, About M-Reader, para. 1)

Although written logs, journals or book reports can be effective, the MoodleReader or MReader are free programs currently used in hundreds of ER programs throughout the world.

Making Quizzes

Quizzes are essential to the success of an ER program managed by MoodleReader. When no quiz is available, that book will very likely go unread. The greatest challenge is that there are thousands of titles which do not have quizzes. The quiz-making task falls on the shoulders of volunteer teachers and free-lance quiz-makers who contract with publishers.

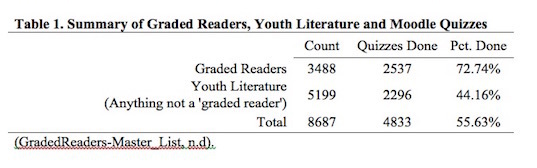

As summarized in Table 1, there are nearly 3,500 graded readers, and the coverage for these titles is greater than 70%.

However, there are far many more so-called “leveled readers.” These books’ lexis and syntax are usually controlled but the target audience is first-language readers. In addition, there is a vast amount of youth literature, books aimed at young readers in their first language. These books often appear in ER collections and so if they are to be included in the MoodleReaders, quizzes must be made for them as well.

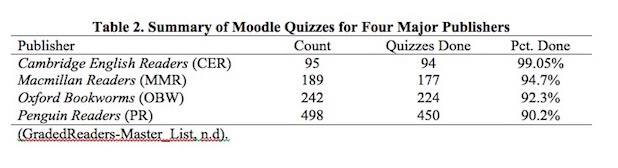

Turning to graded readers, and specifically to the major publishers whose titles commonly appear ER collections, the rate of coverage is higher than 90%, as seen in Table 2.

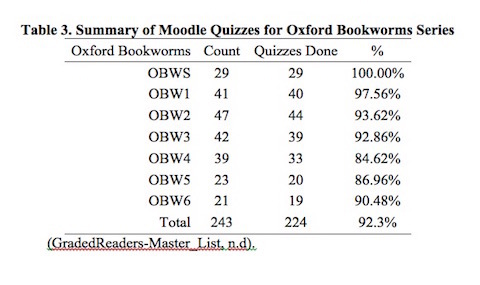

The Oxford Bookworms series, perhaps one of the most popular, has a high rate of coverage, especially at the lower levels. Oxford University Press publishes about 7-10 new Bookworms titles each year, so quizzes must be made for those as well. (See Table 3.)

As can be seen from the section above, quiz-makers are constantly playing catch-up as publishers create more and more series and publish new titles in existing ones. It would be a great service to the ER community if publishers could provide ready-made quizzes for their books.

Procedure for Making Moodle Quizzes

Now, let’s turn to the actual process of making quizzes. The procedure can be summarized in these five steps:

- Identify books that need quizzes to be made.

- Read the book(s).

- Make questions in GIFT format according to the Guidelines.

- Submit the quiz for processing into Moodle.

- Download the quiz for MoodleReader.

The first step for the quiz-maker is to identify which books do not have quizzes. The Extensive Reading Foundation provides Google docs spreadsheets with publishers’ lists of books, searchable by individual publishers (https://sites.google.com/site/erfgrlist/). In addition to word count, yomiyasusa (YL) level and other data, the site indicates if a quiz is available for the MoodleReader. It is important that quiz-makers do not duplicate their efforts, so care should be taken before embarking on making a quiz.

Once a title has been identified as not having a quiz, the quiz-maker should read the book. For longer books, the quiz-maker may need to read it more than once, especially if the book could not be finished in one sitting.

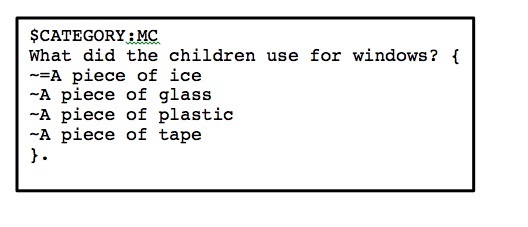

Quizzes must be created in a text-based file according to a GIFT format. This is a kind of coding that is then processed so that the quiz will properly display on the MoodleReader. A template is available from http://moodlereader.org. Novice quiz-makers may be slightly intimidated at first, but after a period of getting accustomed to the format, it is relatively straight-forward as shown in Figure 1.

Detailed guidelines for making quizzes are available at http://moodlereader.org. There are many factors to be taken into consideration when making a quiz. The nature of the book will determine the most suitable question types. For example, a non-fiction may not have a sequence of events, but could describe a process, which could be used in the ordering question type. Because the quiz the student takes usually has 10 questions, the question bank should have at least 20-30 questions in it. Of course, it is better to have as many questions as possible, because the more questions there are, the more randomized they become in the MoodleReader.

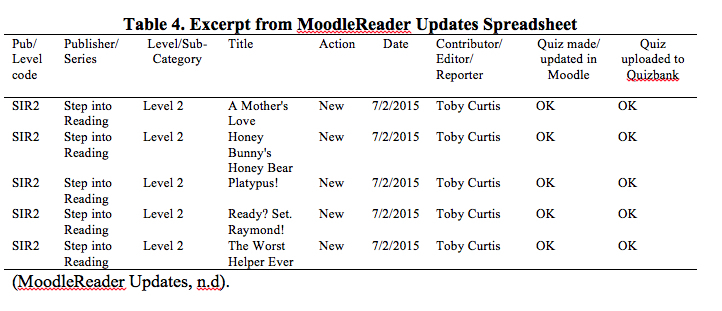

Once the quiz has been made, it must be sent for processing. During processing, the quiz will appear on the MoodleReader Updates spreadsheet, as below. Once it has been processed, it will be marked OK in the Quizbank column and is now ready for download to the users’ MoodleReader as shown in Table 4.

Finally, once the quiz has been uploaded, there is a review process by the Quiz Quality Assurance project, a team of volunteers who review quizzes, looking out for faulty questions, coding and spelling errors.

Conclusion

The author’s motivation to make Moodle quizzes sprang from personal and institutional needs. First, when a coordinated curriculum was adopted in the Faculty of Engineering, all engineering majors (n=560) were required to do extensive reading for one year in their general-education English courses. Although teachers have autonomy on how they choose to evaluate ER, the author and several other teachers adopted the MoodleReader. However, numerous students claimed to have read books for which there were no quizzes. In other words, our ER collection did not match up well to the MoodleReader quiz database. To address this problem, students were allowed to write book reports. However, “resourceful” students quickly caught on to this fact and soon more and more students were submitting the same book reports that had previously been submitted by other students. These students were often, though not always, behind in their reading and were trying to avoid taking quizzes. Thus, the need was obvious to fill the gaps between our ER collection and the quizzes available on the MoodleReader. In addition, the author felt compelled to create quizzes to contribute to the effort to promote ER through the MoodleReader.

The second reason is that, as the MoodleReader became more robust, it made it possible for non-English teachers to use it. This was key in extending our ER program beyond one year. When the engineering students entered their second year, there were required courses in English for Specific Purposes (ESP), but no ER program. At many universities in Japan, it is common for science and technology faculty to teach courses in English for Specific Purposes (ESP). If there were a quiz for every title in our collection, then it would be easier to persuade the Engineering faculty to include an ER component, managed through MoodleReader, in the students’ second year.

Then, at the 2012 ER World Congress held in Kyoto, Japan, Matthew Claflin offered a workshop in which attendees could try their hand at making quizzes for books in the Oxford Reading Tree series. From that point, the author became a regular quiz-maker, writing several hundred quizzes. A positive by-product of making quizzes is that teachers become intimately familiar with the books that students are reading. This possibly encourages more teacher-student interaction and can serve as a point of contact between teacher and learner. Secondly, if students know the teacher is also reading the books, the the teacher becomes a role-model, which is considered key to the success of an ER program (Day & Bamford, 1998).

References

Bieri, T. (2015). Implementing M-Reader: Reflections and reactions. Extensive Reading in Japan, 8(2), 4-7.

Brierley, M., Ruzicka, D., Sato, H., & Wakasugi, T. (2010). The measurement problem in Extensive Reading: Students’ attitudes. In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT2009 Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: JALT.

Campbell, J., & Weatherford, Y. (2013). Using M-reader to motivate students to read extensively. In Extensive Reading World Congress Proceedings, 2, 1-12. Retrieved from <keera.or.kr/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/ERWC2-Proceedingsfinal.pdf>

Day, R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ERF Graded Reader List (n.d.) Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/erfgrlist/

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grabe, W. (2010). Fluency in reading – thirty-five years later. Reading in a Foreign Language, 22(1), 71-83).

GradedReaders-Master_List (n.d). Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/13yJmxcjz28XwREHYZ7VgM1eBGhqlw8tFSZ90ZztUSmU/edit#gid=9

Iwahori, Y. (2008). Developing reading fluency: A study of extensive reading in EFL. Reading in a Foreign Language, 20, 70–91.

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power or reading: Insights from the research, 2nd Edition. Connecticut: Heinemann/Libraries Unlimited.

Moodlereader. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://moodlereader.org

MoodleReader Updates (n.d). Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1uB15-xRJ04D6a7iMiW7Ayrvm-1ZTu1fxjrAkO7pERtQ/edit?hl=en#gid=637122183

M-Reader. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://mreader.org

Nation, P. (1996). The four strands of a language course. TESOL in Context, 6(2), 7-12.

Prowse, P. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading: A response. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2), 142-145. Retrieved from nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/October2002/discussion/prowse.html

Robb, T. (2002). Extensive reading in an Asian context: An alternative view. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2), 146-147.

Robb, T. (2008). The reader quiz module for extensive reading. Retrieved from http://moodlereader.org/moodle/mod/resource/view.php?id=492

Robb, T. (2015). Quizzes – a sin against the sixth commandment? In defense of MReader. Reading in a Foreign Language, 27(1), 146-151.

Robb, T., & Kano, M. (2013). Effective extensive reading outside the classroom: A large-scale experiment. Reading in a Foreign Language, 25(2), 234-247.

Stoeckel, T., Reagan, N., & Hann, F. (2012). Extensive reading quizzes and reading attitudes. TESOL Quarterly, 46(1), 187-198.

Waring, R. (2009). The inescapable case for extensive reading. In A. Cirocki (Ed.), Extensive reading in English language teaching (pp. 93-111). Munich, Germany: Lincom.