Chapter Seven: An Evaluation of Progress Measurement Options for ER Programs

York Weatherford & Jodie Campbell

Kyoto Notre Dame University, Japan

Abstract

In any Extensive Reading (ER) program, one of the most important factors in assessing and evaluating students is how many books the students have read. Thus, it is important to keep a record of the total number of books or the total number of words students have read, as well as the level of those books. It is also important to remember that there is nothing in the ER literature that says teachers cannot keep records of their students’ ER or give them grades based on their ER. However, assessing and evaluating student progress in an ER program can be challenging, as every student has a particular preference for how they wish to be assessed. This paper, a continuation of two previous studies (Campbell & Weatherford, 2013; Weatherford & Campbell, 2015), is based on surveys of first- and second-year Japanese university English majors who were asked which assessment and evaluation method they preferred in their ER—book reports or the M-Reader online quiz system (a free online graded reader assessment system that checks whether students have read their books). This paper will start with a brief discussion of assessment in ER. Then it will discuss some arguments to consider concerning assessment and evaluation of students’ ER and examine some current and typical assessment and evaluation methods for ER. The survey results will then be discussed, showing an overwhelming preference for M-Reader. Finally, an analysis of the students’ reasons for choosing M-Reader as their preferred method of assessment will be provided.

Assessment in ER

Extensive Reading (ER) is a method of language learning that involves students reading a large amount of easy-to-read and enjoyable books in order to develop reading speed and fluency. The Extensive Reading Foundation’s Guide to Extensive Reading states, “When students are reading extensively, they READ: Read quickly and Enjoyably with Adequate comprehension so they Don’t need a dictionary” (2011, p. 1). Harold Palmer, the first person to use the term ER in foreign language pedagogy, argued that ER meant “‘rapidly’ reading ‘book after book’”, and the “reader’s attention should be on the meaning, not the language, of the text” (Day & Bamford, 1998, p. 5). In addition, numerous published articles and books conclude, as Nuttall (1982) argues, that second language (L2) learners fall into “the vicious circle of the weak reader” (p. 167): they read slowly, they don’t enjoy their reading, they don’t read much, and they don’t understand. What ER tries to do is to break that vicious circle and get the L2 learner into the “virtuous circle of the good reader” (Nuttall, 1982, p. 168): they read faster, they read more, they understand better, and they enjoy reading. In addition, one of the basic principles of ER is that students should read with minimal accountability (Krashen, 2004). In other words, assessment should be kept to a minimum. In educational settings, however, teachers are required to assess and evaluate their students for institutional purposes. Therefore, teachers managing an ER program need some way of keeping track of their students’ reading progress. While there are plenty of assessment and evaluation methods in the ER literature (see Typical Assessment and Evaluation Methods of ER below), ER teachers are still skeptical as to whether or not these methods provide sufficient evidence that students have read the books they claim to have read. Fortunately, the M-Reader online quiz system, a rewritten version of the original Moodle Reader, “a free online graded reader assessment system that assesses whether students have read their books” (Robb & Waring, 2012, p. 168), is becoming more and more popular in the ER world as a reliable and valuable ER assessment and evaluation tool, thus holding students accountable for their reading.

Day and Bamford (1998) argue, “There is nothing about extensive reading that says that requirements cannot be set, records kept, or grades given as in other forms of instruction” (p. 86). However, a controversial issue to consider is whether ER programs and teachers should in fact check how well a student has understood a book (a graded reader) they have read (Nuttall, 1982). There are two views here: one in favor of assessment and evaluation of students’ ER, and the other against it. Unfortunately, there is not a lot of research in the ER literature that discusses which is the best method for assessing and evaluating students’ ER. According to Sargent and Al-Kaboody (2014), “There is a surprising lack of methodical investigation into the ways in which ER might be assessed” (p. 3). Robb (2009) also argues that many ER researchers and advocates are convinced of the effectiveness and power of ER in L2 learning, but others are concerned with “student management issues, particularly the need of an efficient mechanism for holding students responsible for actually doing the reading” (p. 109). Thus, ER programs and teachers are free to choose which assessment and evaluation method best suits their students’ ER needs. As Nuttall contends, ER teachers can choose either view, or both (1982). The authors of this paper are in favor of assessment and evaluation of their students’ ER via the M-Reader online quiz system. According to Tom Robb (2015), the creator of M-Reader, it is:

Designed to be an aid to schools wishing to implement an Extensive Reading program. It allows teachers (and students) to verify that they have read and understood their reading. This is done via a simple 10-item quiz with the items drawn from a larger item bank of 20-30 items so that each student receives a different set of items (para. 2).

As of November, 2015, there are over 4800 quizzes available via 117 different ER graded reader series (publishers) on the M-Reader website with a current user base of about 80,000 students in about 25 countries (Robb, 2015).

Assessment and Evaluation Arguments to Consider

Waring (1997) makes a very valid argument concerning assessment and evaluation of ER, contending that if we test students on their ER, then students may regard the purpose of their ER as test preparation, which is the opposite of one of the ten characteristics of an ER approach to second language (L2) learning: “#4: The purposes of reading are usually related to pleasure, information, and general understanding” (Day & Bamford, 1998, p. 8). Krashen (2004) argues that there should not be any kind of evaluation (e.g., book report evaluation) and that students should just read for the pleasure of reading, while Nutall argues that testing students encourages them to cheat, and as soon as grades or marks are considered, enjoyment tends to disappear and reading for pleasure becomes reading for credit (1982). Day and Bamford also maintain that answering comprehension questions hinders self-motivation and independence (1998). We have seen that there are many ER educators who feel that students should not be assessed and evaluated on their ER, and to strengthen this view is an argument from the Extensive Reading Foundation’s (2011) Guide to Extensive Reading:

Teachers often feel they should check students’ understanding of their reading directly through tests and quizzes or even just to assess whether the reading has been done. In Extensive Reading, as long as students are reading a book at their level, there is then no need to test their comprehension. This is because part of the decision about which book to read involved making sure they could understand most of the book before reading it. Extensive Reading is not about testing (p. 9).

This is a very powerful argument to consider for ER programs and teachers as both

views—in favor of ER assessment and evaluation, or against it—can be considered acceptable in the ER literature (see Day & Bamford, 1998). However, according to the Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER) Guide to Organizing Programmes of Extensive Reading, checking the ‘quality’ of students’ ER is very important as it is very easy for a student to borrow a book and then return it without even reading it (1992). The EPER’s guide offers numerous ways to check whether or not a student has read a book or not, one of which is via book reports, where students are asked to write a report on each book they read. However, Weatherford and Campbell (2015) conclude, “Book reports can be easily faked” (p. 662). Therefore, the authors believe that an additional method of assessment such as the M-Reader online quiz system is necessary as it obviates “the need for other more cumbersome and laborious measures such as book reports or summaries” (Robb, 2015, p. 146). In addition, M-Reader can boost students’ self-efficacy and increase students’ motivation. As one student said, “I think this is the perfect program for raising my English ability. It was really fun, so I want to read more and take more Moodle quizzes” (Miller, 2012, p. 80, as cited in Robb, 2015, p. 149). The next section will examine some of the other typical assessment and evaluation options in ER.

Typical Assessment and Evaluation Methods of ER

Typical Assessment and Evaluation Methods of ER There is a vast array of assessment and evaluation methods in ER for checking whether students have read the books they claim to have read. Here are some of the more popular methods:

Day and Bamford (1998):

- Written reports

- Answers to questions

- Number of books read

- Reports turned in

- Assign a certain number of books or pages to be read (e.g., a book a week)

- Reading notebooks

- Weekly reading diary

- Reading tests (Cloze tests)

- Negotiated evaluation (e.g., forming book promotion teams; writing sequels)

Bamford and Day (2004):

- One-minute reading (via a pre- & post-test on the first & last day of the semester)

- Cloze Test (to test the impact of ER on proficiency)

- One-sentence summary test

- Speed answering

Bernhardt (1991):

- Cloze test

- Multiple-choice tests & T/F tests (She argues these tests are problematic because they are not passage-dependent.)

- Direct content questions

- Alternative method is to use Immediate Recall

Oxford University Press (2015) (from downloadable materials available to registered users):

- Activity worksheets

- Exercise answers

- Editable tests

- Fill in the gaps

- Matching questions

- Who said this? Who thought this?

- T/F

- Missing words

- Choose the best answer

EPER Guide to Organizing Programmes of ER (1992):

- Checking entries on a wall chart

- Checking book reports in a reading notebook

- Personal interviews

- Matching titles with students

As you can see, the range of methods for assessing and evaluating students’ ER is wide. However, the authors use only two of the methods as their main source of students’ ER assessment and evaluation: book reports and the M-Reader online quiz system.

Research Design

The following sections are based on the same format employed in Weatherford and Campbell (2015). New survey data are compared with the data in that paper.

Participants

Participants were 107 freshman and sophomore university students majoring in English in the Department of English Language and Literature at a small women’s university in Western Japan during the first semester of the 2015 academic year. All of the second-year students had previous experience with ER and M-Reader during their first year. Extensive Reading was a requirement for the Reading Lab course (described below) that all of the participants were enrolled in. The first-year students’ reading goal was between 40,000 and 80,000 words per semester, depending on their level of English proficiency. The goal for all second-year students was 80,000 words.

Reading Lab

Reading Lab is a new course that was introduced in the 2014 academic year. Although not a required course, all first- and second-year students in the Department were strongly encouraged to enroll, and most did. Reading Lab is essentially an independent study course, and students are not required to attend classes other than an orientation session on the first day. This initial session introduced students to the principles of ER and provided an orientation to M-Reader. ER/M-Reader accounted for 50% of the grade in this half-credit course. The other 50% was based on the students’ performance on WordEngine (an online vocabulary-learning system) for first-year students and participation in Moodle Forums for second-year students.

Materials & Methods

Students were asked to complete a survey to indicate their opinions of ER as a learning method and to provide their evaluation of M-Reader as an assessment tool. The survey was completed at the end of the first semester in July 2015. We used a paper-based questionnaire in Japanese (see Appendix for a translated English version), which the students completed in approximately ten minutes during the final class session. In order to keep track of the data and to sort the students into groups, students were asked to provide their university ID numbers. Although the survey was not completely anonymous, students were assured that they would not be identified by name and that their responses would not affect their grades.

The survey included 36 individual items: one question about the number of books students took quizzes on; 12 six-point Likert scale items to gauge student opinions of the enjoyment and the usefulness of the reading materials; four semantic differential items concerning the difficulty of the books; five semantic differential items about the M-Reader website; one multiple-choice question regarding students’ assessment preferences (M-Reader versus book reports, with the option to select “other”); and one multi-select multiple choice question with eight options for each choice (M-Reader or book reports) regarding students’ reasons for their preferences. These reasons were based on student responses to an open-ended question on a similar survey administered in the first semester of the 2013 academic school year (Campbell & Weatherford, 2013), plus some additional reasons that were expected as possible responses. Finally, one open-ended question asked students who did not take any quizzes to explain their reasons why.

Analysis

The results were analyzed with Stata Statistical Software (v. 12) using a two-sample t test with unequal variances. This test was used to determine if the means of different groups were equal. We compared the results of two groups: students who chose M-Reader versus those who chose book reports. We considered the means to be different at the 0.10 significance level.

Survey Results

Assessment Preferences

The students indicated an overwhelming preference for M-Reader (84%) over book reports (16%), and no students selected “Other.” However, there was a slight discrepancy between the first- and second-year students’ preferences. First-year students (n=56) preferred M-Reader to book reports 91% to 9%, while second-year students (n=51) indicated a slightly higher preference for book reports (24%) compared to the first-years. These results contrast considerably with previous results where students were nearly evenly divided overall (56% for M-Reader versus 44% for book reports), and freshmen and sophomores indicated practically opposite preferences, with a majority (74%) of freshmen preferring M-Reader and a majority (69%) of sophomores preferring book reports (Weatherford & Campbell, 2015). It is important to note here that the previous results were based on responses from students who matriculated before the Reading Lab course became part of the curriculum. Further analysis will be provided in the Discussion section.

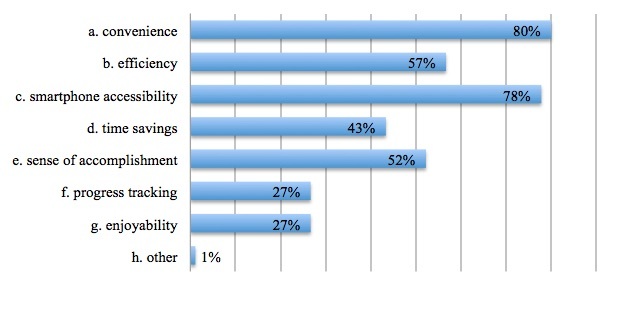

After stating their preferences, respondents were asked to indicate their reasons. They were given seven options (plus “other”) to choose from and were instructed to choose as many reasons as applied (see Appendix, questions 10A and 10B). The results for M-Reader are shown in Figure 1.

These results are nearly the same as those reported in Weatherford and Campbell (2015), with one notable exception. In both cases, the convenience of accessing the quizzes on the Internet was the most common reason for preferring M-Reader. However, in the most recent survey, the ability to access M-Reader on smartphones is a close second at 78%, whereas only 54% of respondents selected this option in the earlier survey. This is likely a consequence of the proliferation of smartphones over the past few years.

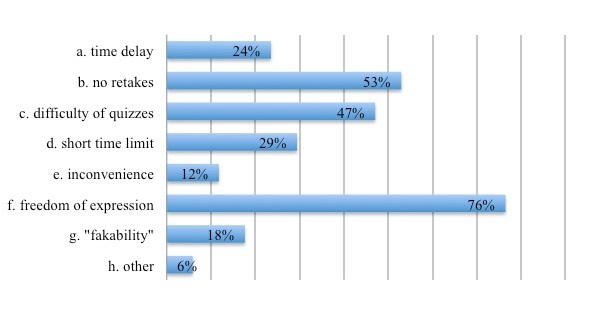

The reasons for preferring book reports are shown in Figure 2. Notice that most of the reasons are complaints about M-Reader rather than the merits of book reports themselves.

Overwhelmingly, the most popular choice was f.: “I can express myself freely in a book report.” This contrasts significantly with the previous survey results, where 81% of respondents selected a.: “The 24-hour time limit between quizzes is too long.” This means that students did not like the way that the M-Reader system was set up to make them wait for 24 hours after finishing a quiz before they were allowed to take the next one. In response to the students’ dissatisfaction with this constraint, the wait time between quizzes was changed to three hours. As a result, the students were not as concerned with the time delay in the most recent survey.

Number of Quizzes Taken

Students were asked to indicate the number of quizzes that they took during the semester by selecting a range (1=0, 2=1–2, 3=3¬–4, 4=5–6, 5=7–8, 6=9–10, and 7=more than 10 quizzes). As reported in Weatherford and Campbell (2015), students who stated a preference for M-Reader reported that they took more quizzes on average (μ=5.7) than those who preferred book reports (μ=4.3, p= 0.012)

Opinions about Graded Readers

Table 1 illustrates the students’ opinions of graded readers, comparing the average responses of the M-Reader (MR) group with the book report (BR) group. This data is based on 12 six-point Likert scale questions, where 6=strongly agree and 1=strongly disagree.

Table 1. Opinions of Graded Readers

| Item | MR | SD | BR | SD | p |

| a.fun reading materials | 4.133 | 1.265 | 3.000 | 1.369 | 0.002 |

| b.enjoyable as English learning materials | 4.233 | 1.237 | 3.353 | 1.412 | 0.012 |

| c.something I looked forward to reading each week | 3.022 | 1.245 | 2.294 | 1.160 | 0.013 |

| d.not my favorite assignment | 3.678 | 1.253 | 3.765 | 1.640 | 0.419 |

| e.boring reading materials | 2.811 | 1.141 | 3.294 | 1.263 | 0.078 |

| f.materials that I want to keep reading during vacation | 3.056 | 1.155 | 2.118 | 1.269 | 0.004 |

| g.useful for increasing my vocabulary | 4.278 | 1.218 | 3.529 | 1.625 | 0.043 |

| h.useful for improving my reading fluency | 4.389 | 1.251 | 3.588 | 1.661 | 0.036 |

| i.useful for improving my reading comprehension | 4.544 | 1.153 | 3.647 | 1.618 | 0.020 |

| j.useful for improving my reading speed | 4.433 | 1.218 | 3.471 | 1.505 | 0.010 |

| k.useful for improving my overall English ability | 4.378 | 1.066 | 3.588 | 1.543 | 0.028 |

| l.unsuitable as English teaching learning materials | 2.278 | 1.071 | 2.824 | 0.951 | 0.022 |

As reported in the previous survey (Weatherford & Campbell, 2015), students who preferred M-Reader were more favorable toward graded readers than those who chose book reports. As expected, the averages for all of the items with a positive attitude toward graded readers (a, b, c, f, g, h, u, j, k) were significantly higher among the M-Reader group, and the averages for the negative items (d, e, l) were significantly lower.

The opinions concerning the difficulty of graded readers are shown in Table 2. Although the M-Reader group appears to have found the books less difficult than the book report group, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant.

Table 2. Difficulty of Graded Readers

| Item | MR | SD | BR | SD | p |

| a. too easy/difficult | -0.067 | 1.305 | 0.412 | 1.622 | 0.132 |

| b. familiar/unfamiliar words | -0.1 | 1.454 | 0.412 | 1.734 | 0.133 |

| c. not at all/extremely difficult to read | 0.011 | 1.639 | 0.471 | 1.908 | 0.182 |

| d. easy/difficult to finish | 0.2 | 1.595 | 0.588 | 1.938 | 0.223 |

Opinions about M-Reader

The students’ opinions of the M-Reader website were measured using five semantic differential items. The mean results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Opinions about M-Reader

| Item | MR | BR | p |

| 4. The M-Reader website was difficult to use/easy to use | 0.578 | -0.706 | 0.014 |

| 5. The M-Reader quizzes were difficult/easy | -0.7 | -1.176 | 0.153 |

| 6. The 15-minute time limit was insufficient/sufficient | 0.2 | -0.941 | 0.020 |

| 7. Reaching the word-count goal was difficult/easy | -1.133 | -1.765 | 0.064 |

| 8. The time delay was short/long | 1.078 | -0.176 | 0.021 |

In this instance, larger averages indicate a more positive opinion of the website, except in the case of item 8. Predictably, students who preferred M-Reader were generally more positive: they found the site easier to use, the quizzes easier to pass (although this item was not statistically significant), the time limit sufficient, and the word-count goal easier to reach. However, the M-Reader group indicated that they felt the time delay between quizzes was too long compared to the students who preferred book reports. Although this result seems to exhibit a negative stance toward M-Reader, other explanations will be explored in the following Discussion section.

Discussion

The results of this survey revealed an overwhelming preference for M-Reader over book reports. These results contrast significantly with those reported in Weatherford and Campbell (2015), where the students were evenly divided. One major difference between the two studies was the introduction of the Reading Lab course in the 2014 academic year. All of the respondents in the current survey were enrolled in Reading Lab, while none of the students in the previous survey had taken the course. M-Reader performance accounted for half of the students’ grades in the Reading Lab course, whereas extensive reading had previously made up only a small portion of the students’ grades in their required Reading courses. It should also be noted, however, that only a small portion of the respondents to the most recent survey had been required to write book reports. (One teacher had his first- and second-year Reading classes of approximately 20 students each write a book report every two weeks.) That means that it is possible that most students indicated a preference for M-Reader because that was the assessment method they were most familiar with. However, it is also possible that students could imagine that doing book reports might require more effort or be otherwise less desirable than taking M-Reader quizzes. In future surveys, additional questions may be added to clarify this issue.

The other results of the current survey are comparable with previous surveys. As in past surveys, students who preferred M-Reader took more quizzes and were more positive about the enjoyment and usefulness of extensive reading than students who said they would rather write book reports. In addition, students in the M-Reader group were unsurprisingly more positive about the functionality of the M-Reader website itself, except in the case of the imposed time delay between quizzes. However, this may not be so much a criticism of M-Reader as an indication of the students’ eagerness to keep reading and taking quizzes. This should be taken as an encouraging sign for proponents of ER and M-Reader. After all, most survey respondents indicated a preference for M-Reader, which suggests that a majority of students have gained an understanding of the value of Extensive Reading.

Conclusion

Among all of the ER assessment and evaluation options available, the authors believe that the M-Reader online quiz system is the best method for ensuring students have actually read the books they claim to have read. M-Reader also provides an efficient and reliable system for keeping track of the students’ reading progress. In addition, the survey results reported in this paper demonstrate that students are generally in favor of M-Reader. Following the arguments of Robb (2015), the authors feel that even though ER principles originally presume that students should be reading simply for the pleasure of reading without any follow-up activities, teachers need some kind of system where they can keep track of whether students have done their reading or not. Moreover, in institutions where not every student is motivated to study or read extensively, some tracking method of students’ ER is required. The M-Reader online quiz system is therefore the best assessment method to date for accomplishing this without adding any extra work for teachers.

References

Al-Kaboody, M., & Sargent, J. (2014). The effects of tests on students’ attitudes and motivation towards extensive reading. Retrieved from https://www.nau.edu/cal/pie/2013-2014-research/

Bamford, J., & Day, R. R. (2004). Extensive reading activities for teaching language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bernhardt, E.B. (1991). Reading development in a second language: Theoretical, empirical, and classroom perspectives. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER). (1992). Guide to organizing programmes of extensive reading. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh.

Extensive Reading Foundation. (2011). Guide to extensive reading. Retrieved from http://erfoundation.org/ERF_Guide.pdf

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Nuttall, C. (1982). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language. London, UK: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.

Oxford University Press (2015). Downloads: Get more from your reading! Retrieved from https://elt.oup.com/teachers/bookworms/downloads/

Robb, T. (2015). About M-Reader. Retrieved from http://mreader.org/mreaderadmin/s/html/about.html

Robb, T. (2009). The reader quiz module for extensive reading. In M. Thomas (Ed.), *Selected Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual JALT CALL SIG Conference 2008 (pp. 109-116). Tokyo: Japan Association for Language Teaching.

Robb, T., & Waring, R. (2012). Announcing MoodleReader version 2. Extensive Reading World Congress Proceedings, 1, 168-171.

Robb, T. (2015). Quizzes—A sin against the sixth commandment? In defense of MReader. Reading in a Foreign Language, 27(1), 146-151.

Stata Statistical Software (Version 12) [Computer software]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Waring, R. (1997). Graded and extensive reading: Questions and answers. The Language Teacher, 21(5).

Weatherford, Y. & Campbell, J. (2013). Using M-Reader to motivate students to read extensively. In S. Miles & M. Brierley (Eds.),Proceedings of the Second Extensive Reading World Congress (pp. 1-12). Seoul: Korean English Extensive Reading Association.

Weatherford, Y., & Campbell, J. (2015). Student assessment preferences in an ER program. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & H. Brown (Eds.), JALT 2014 Conference Proceedings (pp. 661-668). Tokyo: JALT.

Appendix

English Translation of the Survey

M-Reader Survey July 2015

Student Number:

Class:

1 How many books did you read and take M-Reader quizzes on this semester?

2 0 2. 1-2 3. 3-4 4. 5-6 5. 7-8 6. 9-10 7. more than 10

If you answered 1 (0 books), please skip to question 11.

How much do you agree with the following statements?

3 The library readers were: Strongly agree Strongly disagree

- fun reading materials. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- enjoyable as English learning materials. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- fun to read every week. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- not my favorite assignment. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- boring reading materials. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- materials that I want to keep reading even 6 5 4 3 2 1 during school vacation.

- useful for increasing my vocabulary. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- useful for improving my reading fluency. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- useful for improving my reading comprehension. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- useful for improving my reading speed. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- useful for improving my overall English ability. 6 5 4 3 2 1

- unsuitable as English learning materials. 6 5 4 3 2 1

What did you think of the levels of the readers?

4 The readers were:

- too easy (in content) -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 too difficult (in content)

- contained only unfamiliar words -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 contained too many familiar

- not at all difficult to read -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 extremely difficult to read

- easy to finish -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 difficult to finish

What did you think of M-Reader?

5 The M-Reader website was difficult to use -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 easy to use

6 The M-Reader quizzes were…difficult -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 easy

7 The 15-minute time limit was…insufficient -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 sufficient

8 Reaching the word-count goal was… difficult -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 easy

9 The time delay between quizzes was…short -3 -2 -1 1 2 3 long

10 Would you prefer to do M-Reader quizzes or write book reports to show that you have read the books?

- M-Reader quizzes (go to question 10A)

- book reports (go to question 10B)

- Other: )

10A Why did you choose M-Reader quizzes? Circle as many of the reasons below that apply.

- It is convenient to take the quizzes on the Internet.

- Taking quizzes is more efficient than writing reports.

- I can take quizzes on my smartphone.

- It does not take a lot of time to take the quizzes.

- I feel a sense of accomplishment when I pass a quiz.

- I can keep track of my reading progress.

- Using M-Reader is fun.

- Other:

10B Why did you choose book reports? Circle as many of the reasons below that apply.

- The time delay between quizzes is too long.

- There is no chance to retake a failed quiz.

- The quizzes are too difficult.

- The quiz time limit of 15 minutes is too short.

- Accessing the Internet is inconvenient.

- I can express myself freely in a book report.

- I can write a book report without reading the entire book.

- Other:

11 If you did not take any quizzes on M-Reader during the semester, please explain why.