Chapter Six: Exploring Teacher’s Practice and Impacts of Extensive Reading on Japanese EFL University Students

Hitomi Yoshida

Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan

Abstract

Among foreign language educators, interest in Extensive Reading (ER) is growing along with questions about how to effectively implement ER in class and its effects. The purpose of the study is to show the effect of ER on three different levels of students in a Japanese EFL university setting over a 14-week semester. An ordinary classroom schedule consists of mainly 3 sections; 1) Repeated Reading to increase reading fluency, 2) Sustained Silent Reading for a block of time to maintain opportunities to read English, 3) Peer Discussion to practice summarizing a book and enhance understanding of the story of books. Students are required to keep a record (reading log) and write a short summary and their reflection (report) on the story after reading each graded-reader book. The teacher’s role in the class is not to impart knowledge as much as guide students and remind them of the purpose of doing ER as a member of a reading community. Results are discussed in light of the importance of extensive exposure to reading over time to build their self-confidence and their attitudes towards reading in English in a positive way. The researcher further explores the role of the teacher in facilitating students’ ER activities.

Introduction

In a foreign language learning setting such as Japan where exposure to authentic language and opportunities to use the target language in natural situations are limited, what learners do outside class takes especially an important role to develop appreciation of the target culture and fluency in the target language. Extensive reading (ER) might be one of the ways to afford learners extra time outside of class to get a good deal of that extra practice they need on a regular basis. ER class activities allow students to choose the books they read depending on their interests and fluent reading level from various interesting topics. Furthermore, copious research evidence bears out the many benefits which come from ER (Day & Bamford 1998; Waring 2000, 2006). Yet, only a few studies on affective aspects of ER activities have been done (Day & Bamford, 1998; Fujita & Noro, 2009; Matsui & Noro, 2010; Robb & Susser, 1989). In addition, there are some practical issues many teachers face which have not been discussed enough such as the effects of ER on different levels of students and a lack of interest in reading among young people. In this study, a questionnaire survey was given to 87 freshman students twice, in Week 1 and Week 14, to observe the effects of ER in a teaching context. As a conclusion, students’ motivational and attitudinal changes toward reading books in English throughout a semester-long ER class during the transition between high school and university is discussed.

Method

Participants

Participants were a total of 87 freshmen that were enrolled in compulsory extensive reading (ER) and intensive reading (IR) classes taught by the author at a university in Japan. They were from three different levels: 1) advanced, 2) intermediate, and 2) low English proficiency classes classified according to their TOEIC score at the time of their entrance exam participated in the study. Students’ ages ranged from 17-19 years and came from the same academic program, School of International Studies. Many of those who are in advanced class have experiences of having studied or lived abroad, and many of those who are in lower class are athletes with special sport skills. Since there was a huge proficiency gap between intermediate and low, the author combined advanced and intermediate students as one group, namely Group AI, and set low students as the second group, namely Group L (Table 1). All the participants were required to take a total of four English subjects weekly, writing and oral communication besides ER and IR during the semester when the study was conducted.

Table 1. Descriptive of Participants

| Level | Group AI | Group L | Total |

| Number of students | 52 | 35 | 87 |

| Male / Female | M=17 / F=35 | M=14 / F=21 | M=31 / F=56 |

Materials

All surveys were completed during ER class time in Week 1 and Week 14. A common approach to the measurement of attitudinal variables is the use of a questionnaire employing a Likert scale. In this study, a questionnaire of this style constructed in Matsui & Noro (2010) and Yamashita (2013) were adopted to support evidence for the instrument’s reliability for students learning English in the Japanese context. In Matsui & Noro (2010), a 31-item questionnaire scored on a Likert scale in the categories of Intrinsic motivation, Self-confidence, Exam-related extrinsic motivation, Internal-related instrumental motivation, and anxiety and negative attitudes toward English reading was administered to examine Japanese junior high school students’ motivation at the end of their program. Yamashita’s (2013) survey was designed to measure five attitudinal variables using a 22-item questionnaire in the categories of Comfort, Anxiety, Intellectual Value, and Linguistic Value. In this study, a questionnaire form using 21 items categorized Intrinsic motivation, Extrinsic motivation, Internet-related instrumental motivation, Anxiety, and Self-confidence was used. (See Appendix.) The reliability of the created instrument was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha which was higher than .881 for Group AI, .890 for Group L in the pretest, and .894 for Group AI and .830 for Group L in the posttest. In addition, book report, reading record, and students’ comments on ER class were collected 3-4 times a semester were used as a part of the data for further analysis.

Procedure

Pretests and posttests regarding reading attitude questionnaire were administered in Week 1 and Week 14 during ER class time. Throughout the course, students were able to access a series of Oxford, Cambridge, Penguin, Macmillan, and Scholastic Readers at the university main library. They could select books and the level according to their interest and proficiency, and read them both inside and outside the class. The ordinary classroom schedule consists of mainly 3 sections; 1) Repeated Reading (fluency practice), 2) Sustained Silent Reading (reading opportunities), 3) Peer Discussion (deeper understanding of a story). Students were required to keep a record and write a short summary and their reflection on the story after reading each graded-reader book. The teacher’s role in the class was not to impart knowledge as much as guide students and participate with them as members of a reading community.

Analysis

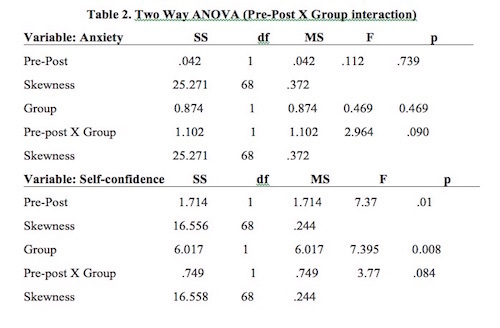

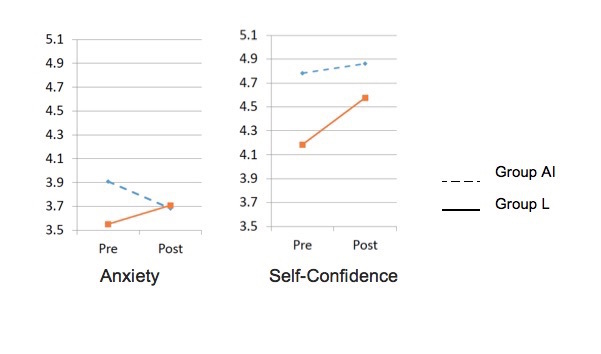

Based on the instrumental design of Matsui & Noro (2010) and Yamashita (2013), this study chose 21 items narrowed down to two aspects of reading attitude for detailed analysis – anxiety and self-confidence. There were four items for Anxiety, and four items for Self-confidence. Responses on conversely worded items (e.g., “I don’t mind even if I cannot understand the book content entirely” to measure Anxiety) were reversed, so that a higher score indicated a higher degree of feeling or belief in that variable. Descriptive statistics for the two variables are summarized in Table 2. A two way ANOVA was run to observe the interaction between Pre-Post test and proficiency group.

Discussion

The results reveal that, the ER class influenced students’ anxiety towards English reading in an opposite way. For Group AI, ER helped lessen anxiety. It was confirmed that anxiety toward encountering unknown words and understanding the book content entirely were reduced. On the other hand, Group L felt more anxious after a semester of ER. Taking a close look at their responses to each item, reading record, and comments, it was observed that their negative change was generated by feeling less competent in relation to goal pursuits, in other words, anxiety has a direct relation with what many students call “an unrealistic goal.” This subsequently affected their selection of books (more difficult level to reach the word count required), which might give no clear differences between IR and ER to them.

As for confidence, both groups of students felt more confident in English. However, the cause of gaining confidence seemed different for the two groups. First, many students in Group AI felt confident of reading many easy English books. They also commented that their confidence was derived from the feeling of using English as a tool. This is understood to mean that they used ER class as a chance and enjoyed using and confirming knowledge what they had studied. For Group AI, it is also inevitable to say that due to a ceiling effect, no significant change in self-confidence was confirmed. On the other hand, the cause of positive change in Group L derived from a comparison with IR. From their comments, it was understood that they compare ER and IN and responded they felt self-confidence and satisfaction after completing a story, which they were not capable of with IR materials. Also, it was pointed out that they rather felt development in their summarizing skills or logical thinking than reading fluency.

Conclusion

The affective domain of ER has received less attention than has the cognitive domain in previous studies. The present study has gone a step further into the affective domain and examined our understanding of the impact of ER for different levels of students. It revealed that a semester length ER class influences university freshmen’s attitudes towards English reading after introducing ER. Many of them have long studied IR to prepare their university entrance exam. After experiencing ER for the first time, ER helped enhance self-confidence in both advanced and low level students. However, the lower group had anxiety towards English reading due perhaps to their basic proficiency level or because of the teacher’s guidance. This implies that meticulous, individual-targeted teaching is needed. With regards to understanding the logic behind their responses, further qualitative investigation is necessary.

References

Day, R. R. & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Day R. R., & Bamford. J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language,14(2), 136-141.

Fujita, K., & Noro, T. (2009). The effects of 10 minute extensive reading on the reading speed, comprehension and motivation of Japanese high school EFL learners. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan, 20, 21-30.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Maley, A. (2008). Extensive reading: Maid in waiting. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), English language learning materials: A critical review. London/New York: Continuum, 133-156.

Matsui, T., & Noro, T. (2010). The effect of 10-minute sustained silent reading on junior high school EFL learners’ reading fluency and motivation. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan, 21, 71-80.

Prowse, P. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading: A response. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2).

Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. (Eds.) (2002). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics (3rd ed.). London: Longman.

Robb, T. N. & Susser, B. (1989). Extensive reading vs skills building in an EFL context. Reading in a Foreign Language, 5, 239-251.

Waring, R. (2000). The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of using graded readers. Oxford University Press, Japan, Retrieved from http://extensivereading.net/docs/tebiki_GREng.pdf

Waring, R. (2006). Why extensive reading should be an indispensable part of all language programmes. The Language Teacher, 30(7), 44-47.

Yamashita, J. (2013). Effects of extensive reading on reading attitudes in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 25(2), 248-263.

Appendix

Reading Attitude Questionnaire Items

F1: Intrinsic motivation

19 I want to learn more about English culture and customs through English.

15 I want to broaden my views by reading English books.

2 I want to study reading most of all English skills.

18 I want to acquire new knowledge by reading English books.

6 I learn English reading because I want to read newspapers and magazines in English.

10 I enjoy reading English books.

F2: Self-confidence

8 I am very confident of reading many easy English books.

16 Reading many easy English a lot is not difficult for me.

1 It is easy for me to read many easy English books.

13 I don’t care even if I can’t understand the contents of a book.

F3: Extrinsic motivation

20 I read English books to pass entrance exams.

7 I read English books to become good enough to pass entrance exams.

3 I read English books because most of my friends do.

12 I read English books to get better grades.

F4: Internet-related instrumental motivation

21 I read English book because I want to get information on the Internet.

11 I want to look up new words in the dictionary while I am reading.

9 I read English books because I want to exchange e-mails in English.

F3: Anxiety

5 I feel anxious if I don’t know all the words.

17 I sometimes feel anxious that I may not understand even if I read.

4 I feel anxious when I am not sure whether I understood the book content.

14 I don’t mind even if I cannot understand the book content entirely.