Chapter Four: Longitudinal Case Study of a 7-year Long ER Program

Hitoshi Nishizawa & Takayoshi Yoshioka

National Institute of Technology, Toyota College, Japan

Abstract

The duration of an ER program is an influential factor in EFL settings because, after the initial excitement, elementary EFL learners in ER programs seem to face a challenging period when they struggle to feel improvement before they start to read autonomously. The programs fail to satisfy their students if they end during this period. Therefore, it has practical value to examine how students read and feel in an ER program of long duration.

In this study, we ran a 7-year long ER program at a technical college in Japan, where students were elementary EFL learners when they joined the program. The program has a 45-minute weekly Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) lesson for 30 weeks per year, and 14 students completed the 7-year program. In the program, the average student recognized that he could actually read English texts without translation, increased his scores in standardized tests such as TOEIC, and came to read confidently until the end of the program.

The longitudinal study also revealed the influence of the amount to be read and readability levels of English texts. A million words were confirmed as a valuable milestone for the amount to be read. Reading picture books with high comprehension before stating to read Graded Readers (GR) was an effective practice to overcome the translating habit of Japanese elementary EFL learners, and the amount of reading easy-to-read books especially in early years had a strong influence on how the students improve their English proficiency.

Background

Japanese EFL learners’ English proficiency is generally low as is shown in score distribution of the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC). The TOEIC is a standardized proficiency test of receptive English skills for nonnative speakers of English (Woodford, 1982) widely used in Japan. The institutional program of TOEIC had 1.26 million test takers in 2013 academic year (IIBC, 2014: 5), where 62% belonged to beginner or elementary levels (10 - 490) and 31% stayed in lower-intermediate level (495 - 740). University students’ average scores except language majors also belonged to the elementary level.

Effect of ER Measured with Standardized Tests

ER was an approach rarely practiced in Japanese English education, partly because the benefits of ER had not been shown quantitatively. Even though Gradman and Hanania (1991) reported university ESL students’ TOFEL scores were most strongly correlated with extra-curricular reading among 44 language-learning factors, it obviously required a large amount of reading and long duration. Japanese teachers and learners were wondering if the benefits were large enough for them to alter the current teaching/learning practices. They wanted to know the effect in scores on high-stake examinations or standardized tests.

There were several studies, where the benefit of ER was measured with standardized tests. For example, Mason (2004) evaluated the effect with reading section of TOEIC. 104 Japanese college students major in English had read about 500,000 words in three semesters (1.5 years). 88 students’ TOEIC/Reading scores were measured as pretest and posttest, and the average was 121 and 157 respectively. If we assume the same score ratio of reading part and total score: 0.446 (123.64/277.26) was kept, their TOEIC total score was estimated to be 272 and 353 respectively (increase rate was 0.162 point / a thousand words). The score of the posttest, however, remained still in elementary level, and a half million words may not be large enough.

Amount to be Read and Duration of ER Programs

Sakai (2002) had proposed one million total words as a milestone for ER in Japanese EFL settings based on the experience of his ER program for university engineering majors. A million words was about eight to ten times of the total words read by the university students in Robb and Susser’s ER project (1989) who had read 641 pages in average.

There were a few ER programs in which students actually read the amount close to a million words. Furukawa (2011) reported the average total words were 1.2 million words by 12th graders staying in the sixth-year form of his ER program. Kanda (2009) studied the ER of a university student for three years, who had read a million words. Either program needed longer duration.

Readability of English Texts

Another important aspect for ER in EFL settings is the readability of English texts. Sakai (2002) proposed Japanese EFL learners to start ER from leveled readers, such as I Can Read Books Level 1 (ICR1), series of picture books designed to invite L1 children to reading. They were easier books than the starter-level of GR. Furukawa et al (2005) recognized the impact of Sakai’s (2002) proposal, and compiled a book-list for Japanese EFL learners including the Oxford Reading Tree series (ORT), Foundations Reading Library series (FRL), and starter levels of GR. They also defined the Yomiyasusa level (YL), a readability scale optimized for Japanese EFL learners. The scale is partially based on objective measures such as headwords, grammatical complexity, or length, but also on subjective measures such as how easy typical students find the story (Eichhorst & Sheron, 2013: 8). They were guided by the recognition “Even if a student knows all the words of a text in their decontextualized forms, it is still possible that the student may not comprehend that text” as McLean (2014) stated.

In their ER program guided by Sakai’s (2002) advice and using the booklist of Furukawa et al (2005), Nishizawa and Yoshioka (2011) observed that students in their ER program were reading GR of headwords fewer than 600. The GR were far easier books than the standard books for ER in ESL settings, edited by Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER) (Hill, 1997, cited in Day & Bamford, 1998: 173-212). They argued that Oxford Bookworms Stage 1 (400 headwords) was a standard book-series read by their students whose TOEIC scores were 450 in their program and it was too difficult for elementary EFL learners to read extensively with sufficient comprehension.

Takase (2008) showed the positive effect of reading an average of over 100 very easy-to-read books (YL 0.0 – 1.0) at the beginning of her ER program on Japanese university students. Furukawa (2011) suggested that Japanese EFL learners should read at least 100 thousand words before finishing YL 1.0 (Oxford Reading Tree Stage 9), which was as easy as Takase’s easy-to-read books (2008).

Research Questions

We would like to answer the following three questions in this study. The first question is “Is a million words a valuable milestone for elementary EFL learners?” and the second is “How many years does an ER program need to accomplish it?” We need to improve the students’ English proficiency from elementary level (TOEIC 408): 7th year kosen students (IIBC, 2014: 7) to lower-intermediate level (TOEIC 565): the expected level for newly employed university graduates (IIBC, 2014: 23). We would like to know if seven years is long enough for our students to read a million words when we add one 45-minute weekly ER lesson to traditional English classes.

The third question is “Is it necessary for elementary EFL learners to start their ER from picture books or starter level of GR?” The effect of reading those easy-to-read books must be evaluated by the students’ proficiency improvement in a long-term program.

Method

Subjects and English lessons

The ER program was conducted at a college of technology or kosen that was a specialized institution for early engineering education in Japan. Each of the five departments had a 5-year foundation course (class size from 1st to 5th year was 40 students each) and a 2-year advanced course (class size for 6th and 7th year was 4 students each). Kosen accepted graduates from junior high schools, where they had already learnt English for three years. Fresh kosen students were generally excellent in mathematics and science, but moderate or average grade in English skills. From 10 to 20 % of graduates from foundation course, whose English skills were in the middle range of the class, proceeded to the advanced course.

The subjects of this study were five students (Student A - E) who had entered a kosen in 2006 and nine students (Student F - N) who entered in 2007. They were the seventh year students in 2012 and 2013, and the groups were called as 2012 cohort and 2013 cohort in this study. The students who had studied abroad or stayed in the course shorter or longer than seven years were excluded from this study.

Their English education consisted of traditional lessons basically taught with the grammar/translation method and ER. English classes for the first year were three 90-minute weekly lessons for 30 weeks, in which 30 minutes a week were assigned to ER other than traditional lessons (Table 1).

Table 1. Lesson Units per week for Traditional Lessons and ER

| Year | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | Total | |

| Traditional | 5.3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 + 1 | 2 | 1 + 0 | 23.3 (78%) | |

| ER | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.7 (22%) |

*one unit is a 45-minute weekly lesson for 30 weeks or a 90-minute weekly lesson for 15 weeks

Traditional English classes continued as two 90-minute lessons from the second year to the first half of the fifth year, and a class from the second half of the fifth year to the first half of the seventh year. In-class ER was conducted as a 45-minute weekly lesson from the second year to the seventh year. 150 hours (22% of total 30 units) were assigned to in-class ER during the seven years.

ER activities

Main ER activity was sustained silent reading (SSR), plus some shadowing, and reading while listening. Shadowing was conducted mostly at the first year for the students to familiarize English sound. Reading while listening (LR) was a practice to read English texts along with listening to audio narration of the text. The readers were not supposed to interrupt the narration and were force to read the text at the same speed of the narration. They comprehended the story mainly from the texts but not from the narration. The narration set the reading pace, and was expected to protect the students from their habit to translate English texts into Japanese. It made a good introduction to ER. Around 30% of the students did LR in average, but in turn.

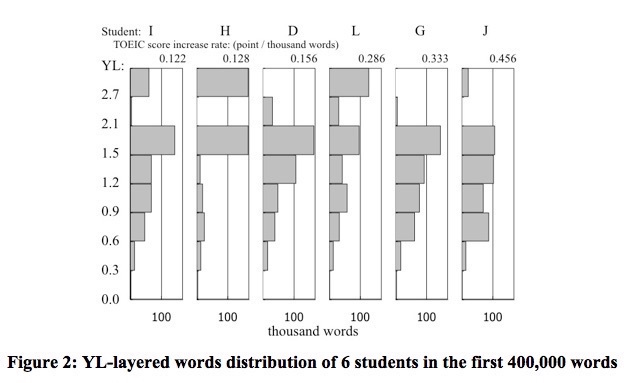

Reading Log All the students had recorded their reading histories in and out of class in their logbooks, which were periodically reviewed by the teachers. The record contained the date, title, series name, YL, word count of the book, cumulated word count, five-graded subjective evaluation of the story, and a short comment describing how the students thought about the story or how they felt about their reading. After the program had finished, available earlier logbooks of six students (D, G, H, I, J, L) were analyzed thoroughly to examine how they had read the first 400,000 words. All the books were categorized by YL and the YL-layered word count were summed.

Evaluation and Analysis We used the total score of TOEIC tests to evaluate English proficiency of the subjects because the test had high reliability and was sensible to English skills of elementary and intermediate levels, and both scores of the reading section and listening section of TOEIC increased in balance in the past studies (e.g., Nishizawa, Yoshioka & Fukada, 2010). The students took from 7 to 16 TOEIC tests in the program from their second to seventh years. Because the date and total word count at the tests were recorded in students’ reading logs, we could analyze the relation of total word count and TOEIC score to estimate the necessary total words to achieve TOEIC 400.

We also analyzed the effect of YL-layered word count in their first 400,000 words upon the TOEIC score increase rates of six students to know the influence of reading easy-to-read books at the start of the ER program.

Finally, we gave the nine students in 2013 cohort a questionnaire to ask two questions: 1) When they felt that they could read English texts fluently; 2) When they felt that they could avoid Japanese in reading English texts. The questionnaire requested the students to describe “when” as a small circle on the 21-centimeter scale (3 centimeters per year), so we could know “when” in one decimal place, for example 4.6 years.

Results

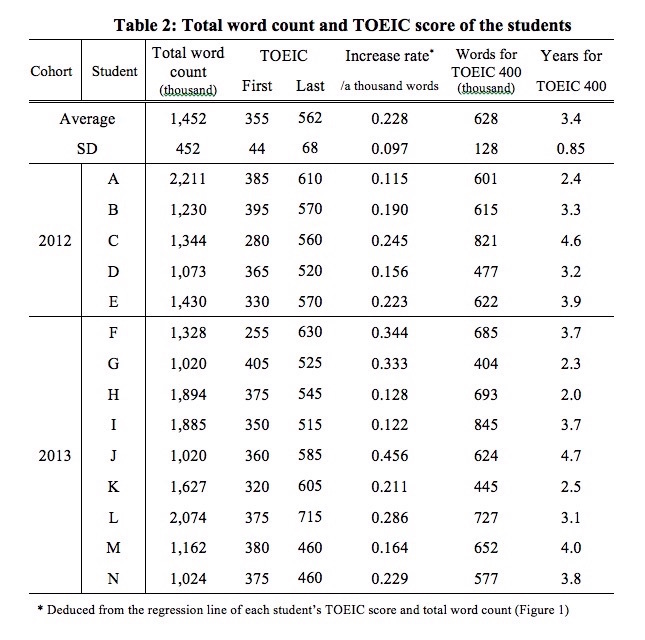

Average total words read by 14 students were 1,452,000 words, and all the students had read at least a million words during the seven years (Table 2). As the result, average TOEIC score increased to 562 with the lowest score of 460, which was a little lower than the border of elementary/lower-intermediate levels (470).

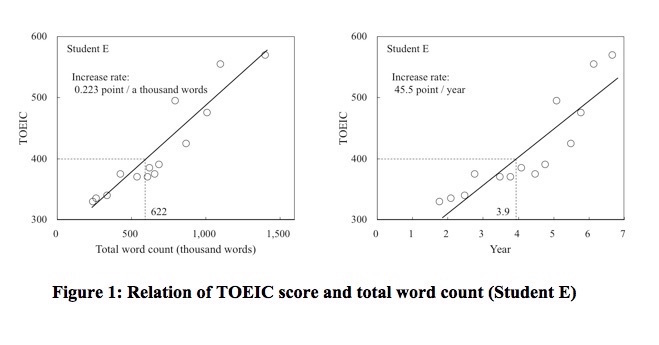

Because the students took from 7 to 16 TOEIC tests during their stay in the program, we could analyze the relation of TOEIC score depending on the total word count (Figure 1).

The student’s TOEIC score increased with the average rate of 0.228 point / a thousand words with a standard deviation of 0.097. The increase rate had a wide variety from the lowest 0.115 to the highest 0.456.

The necessary total word count to achieve TOEIC 400, which was calculated from the regression line of each student’s TOEIC score and total word count as shown in Figure 1, was 628,000 words in average, and the slowest learner needed to read 845,000 words to exceed TOEIC 400. Necessary years to achieve TOEIC 400, which was calculated from the regression line of each student’s TOEIC score versus years in the ER program, was 3.4 years in average, and the slowest learner need to stay 4.7 years to exceed TOEIC 400.

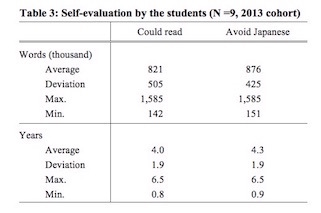

According to the questionnaire to nine students in 2013 cohort, they felt that that they could read English texts fluently when they had read 821,000 words in 4.0 years, and they felt that they could avoid Japanese in reading English texts when they had read 876,000 words in 4.3 years in average. To either of the questions, the slowest learner answered that they needed 6.5 years to feel that way.

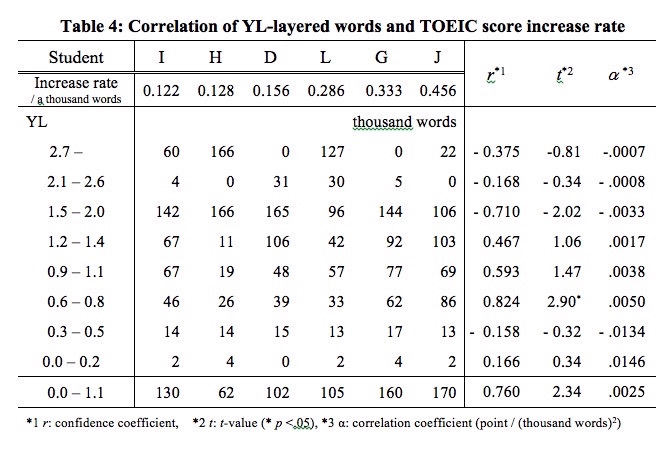

Increase rate of TOEIC score seemed to be influenced by how the student had read in their first 400,000 words (Figure 2). The correlations of the Increase rate and YL-layered word count in their first 400,000 words were negative when the YL was higher than 1.4, but turned positive if YL is lower (Table 4). There was significantly positive correlation for YL 0.6 - 0.8, not-significantly positive correlation for YL 0.8 – 1.0, not-significantly positive correlation for YL 1.1 – 1.4, and not-significantly negative correlation for YL 1.5 – 2.0. Coefficientαfor YL 0.0 - 1.1 suggested that if a student had read 100,000 words more in his first 400,000 words, his TOEIC score increase rate would be 0.25 higher, for example, not 0.132 but 0.387.

Discussion

Total word count to be read and feasibility of the recommendation

We suggest that Japanese elementary EFL learners should read a million words, because average kosen students had read 628,000 words to exceed TOEIC 400, they felt that they could avoid Japanese in reading English texts when they had read 821,000 words, and they also felt that they could read English text fluently when they had read 876,000 words. Many students would enjoy the benefit if an ER program was designed for the students to read the amount.

We believe it is feasible to design an ER program to achieve a million words because it is achievable in 6.2 years with a reading rate of 120 wpm, by using the whole lesson time of a 45-minute weekly SSR lesson of 30 weeks. The yearly word count becomes 162,000 words per year. The necessary duration could be shortened if students read also out of class or increase their reading rate during the program.

The actual yearly word count of this study, 207,000 (1,452,000 / 7) words per year was a little more than the suggested yearly pace or 171,000 words per year for meeting 2nd 1,000 word families twelve repetition in average and learn the vocabulary incidentally (Nation, 2014).

Readability of English texts

We also point out the necessity that elementary EFL learners should read as many easy-to-read books as possible, because the word counts of easy-to-read books (YL 0.6 – 0.8) significantly correlated with TOEIC score increase rate in Table 4, and total word counts of generally easier books (YL < 1.5) rather than more difficult books tended to correlate positively with the increase rate.

We currently propose our students to read 200,000 words from the easiest book of YL 1.1, which were a little more than the word count read by student J (170,000). The recommended amount was seven times the amount set by Eichhorst & Shearon (2013: 37) for top-level Japanese university students, more than the minimum volume recommended by Furukawa (2011), or the 100 books (possibly 50 – 100 thousand words) recommended by Takase (2008).

We assert that reading books from this level may be a key to transform Japanese EFL learners’ default habit of translating English text into real reading, as automatic processing skills in the L1 can produce interference effects and the L2 learner needs to work explicitly to reset associative processing to L2 input by engaging in L2 processing (Ellis, 2005; Ellis, 2006, cited in Grabe, 2009: 150).

Limitations and need of further study

Firstly, the sample size of this study is small, so we have to assume the estimation is rather inaccurate. Repeated studies may estimate the milestone as 670,000 words or 1.5 million words.

Secondly, the estimated amounts to be read may depend on the students’ initial English proficiency and the approach of concurring English lessons. It is possible that older EFL students with more knowledge of English need smaller amounts to enjoy the same benefit. The interaction of ER and concurring English lessons were not discussed in this study.

Thirdly, the necessity of starting ER with the easiest books (YL 1.1) must be examined further for EFL learners of many proficiency levels. Researchers and educators in Japan often argue about this notion, but we did not have enough evidence to support the assertion and we found no arguments from outside of Japan. We do not know yet if the assertion is deeply dependent on Japanese educational settings which are dominated by the grammar-translation approach or if it is applicable to more universal EFL settings.

Conclusion

A 7-year long ER program was conducted for elementary EFL learners in a Japanese technical college. When the students had read 1,452,000 words in average, their average TOEIC score increased from 355 to 562, from elementary level to lower-intermediated level. The students needed to read 628,000 words in average to exceed TOEIC 400. The students felt that they could read English texts fluently when they had read 821,000 words, and that they could avoid Japanese in reading English texts when they had read 876,000 words. These facts suggest that a million words is a necessary amount for a successful ER program for elementary EFL learners.

Reading logs of six students showed that TOEIC score increase rate at around a million words might depend on how much easy-to-read texts they had read in the first 400,000 words. Total word counts of easier-to-read books (YL 1.4) were positively correlated with score increase rate. The recommended books for elementary EFL learners were the easiest level of GR (headwords 300) and easier-to-read picture books such as Oxford Reading Tree series.

References

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eichhorst, D., & Shearon, B. (2013). The Tohoku University Extensive Reading Manual. Sendai: Center for the Advancement of Higher Education, Tohoku University.

Ellis, N. (2005). At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 305-52.

Furukawa, A. (2011). Seven Keys to a Successful Extensive Reading Program. Paper presented at the First Extensive Reading World Congress, Kyoto, Japan, September 3-5, 2011. Retrieved from http://jera-tadoku.jp/papers/ERWC1-FURUKAWA-7_keys.htm

Furukawa, A., Kanda, M., Komatsu, K., Hatanaka, T., & Nishizawa, H. (2005). Eigo tadoku kanzen book guide, 1st Edition [Complete book guide for extensive reading in English, 1st Edition]. Tokyo: CosmoPier.

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a Second Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gradman, H., & Hanania, E. (1991). Language Learning background factors and ESL proficiency. Modern Language Journal, 75, 39-51.

IIBC (2014). TOEIC Test Data & Analysis 2013. Tokyo: The Institute for International Business Communication (IIBC). retrieved from http://www.toeic.or.jp/library/toeic_data/toeic/pdf/data/DAA.pdf

Kanda. M. (2009). A student’s three years of extensive reading: A case study. Heisei Kokusai Daigaku Ronbunshu, 13, 15-31.

Mason, B. (2004). The effect of adding supplementary writing to an extensive reading program. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 1(1), 2-16.

Mclean, S. (2014). Evaluation of the Cognitive and Affective Advantages of the Foundations Reading Library Series. Journal of Extensive Reading, 2, 1-12.

Nation, P. (2014). How much input do you need to learn the most frequent 9,000 words? Reading in a Foreign Language, 26(2), 1-16.

Nishizawa, H., Yoshioka, T., & Fukada, M. (2010). The impact of a 4-year extensive reading program, JALT2009 Conference Proceedings, 632-640.

Nishizawa, H. & Yoshioka, T. (2011). Effectiveness of a long-term extensive reading program: a case study, 42nd Annual BAAL Meeting, Aberdeen, U.K.

Robb, T. & Susser, B. (1989). Extensive Reading vs Skills Building in an EFL Context. Reading in a Foreign Language, 5(2), 239-251.

Sakai, K. (2002). Kaidoku hyakumango [Toward one million words and beyond]. Tokyo: Chikuma shobo.

Takase, A. (2008). The two most critical tips for a successful extensive reading program. Kinki University English Journal, 1, 119-136.

Woodford, P. E. (1982). An Introduction to TOEIC: The initial validity study. TOEIC Research Summary, 0.