Chapter Eight: Implementing Extensive Reading in Japanese as L2 Environment:A Case Using Facebook to Build a Reading Community

Teiko Nakano

Shobi University, Japan

Abstract

Integrating e-learning using graded readers (GR) with the existing curriculum solves the teacher’s difficulty of finding time to embed extensive reading into an already-crowded curriculum. A learning management system (LMS) is effective to build a learners’ community outside the classroom. In this study, international students who are studying Japanese language at a Japanese university were required to read Japanese GRs on their electronic devices and post their comments written in Japanese to Facebook which was a social media tool used by most of the students. The majority posted their comments about GRs and all of the students read each other’s comments, which suggests that it was possible to conduct discussions on Facebook. These results revealed that Facebook is a tool that can possibly replace a LMS and enable teachers to build a reading community outside their classrooms at institutions where a LMS is not used.

Introduction

In higher education programs focusing on Japanese as a second language (JSL), learners of Japanese come from a range of backgrounds. Learners with a first language that does not use kanji (henceforth non-kanji users) often have difficulty with kanji (Chinese characters) in reading. Kumada (2013) indicated that non-kanji users often believe that they are poor readers because they compare themselves to the kanji users in the classroom. Kanji users may sometimes have difficulty because of the difference in pronunciation between their first language and Japanese, but they will still be able to access meaning through the kanji, even though they cannot produce them in an appropriate Japanese way or use them in conversation.

Learning kanji is a major component of Japanese language learning. The Japanese Graded Readers Project Group (JGRPG) has developed a series of Japanese graded readers (GRs) (JGR SAKURA; JGRPG, Tokyo, Japan). JGRPG believes that extensive reading (ER) is an efficient way to learn Kanji, and the same notation of Kanji commonly used by native Japanese speakers is used in JGR SAKURA. All kanji are accompanied by kana, written along side, to show how to pronounce the item. The rationale is that learners who already know the kanji will recognize the meaning of the word, and can thus accelerate their reading rate and comprehension. Learners who do not know the kanji can guess the meaning of the word, including the kanji, from the context in which it is embedded. If learners know how to pronounce the kanji from kana, they can incidentally acquire the kanji through ER (Reynolds, Harada, Yamagata & Miyazaki, 2003).

ER is one aspect of an approach taken in teaching English to speakers of other languages to build vocabulary and develop reading comprehension. Day and Bamford (1998) note that ER encourages students to read and comprehend fluently without using a dictionary, which stands in contrast to intensive reading approaches. Comprehension in ER is conducted using top-down processing in contrast to intensive reading, which relies on a bottom-up approach. Matsuoka (1990) considered ER to be one of the effective approaches to enable intermediate and advanced learners to read and understand at the same time. International students at advanced levels at a Japanese university still need to acquire top-down reading approaches because they have been learning Japanese through an intensive reading approach.

Research Background

One challenging aspect of ER is that it is not a common approach in higher education JSL programs because it is time consuming and qualitatively different to typically offered reading courses. To manage these time constraints, the author implemented a blended ER instruction that involved e-learning and classroom discussion as a noncredit addition to an existing reading course (Nakano, 2013). This method enables learners to use ER outside school hours.

Another issue is that some students with insufficient vocabulary are reluctant readers, although ER is a learning method that can be used by individuals outside the classroom because of the possibilities created by its autonomous learning aspects. Day and Bamford (1998) state the importance of organizing a reading community as a postreading activity that “allow(s) students to support and motivate one another” (p. 141). Day and Bamford (1998) gave examples of postreading activities, such as “writing summaries, writing reaction reports, giving oral reports, and answering questions” (p. 141).

Learning effectiveness was improved by providing learners with information on the progress and achievements of their peers (Kuga, Nakano, Cong, Jung & Mayekawa, 2006). In the previous study, there were learners who had not yet read the assignment and they were encouraged to read by observing the progress of other learners on the web site that the author created (Nakano, 2013). Therefore, it is necessary to maintain students’ motivation to read GRs in between classes by organizing a community where these students can participate with peers. However, because the web site is a passive tool, only the students who logged in could see the progress. Furthermore, the author could not provide a means by which students could receive peers’ comments in real time. Therefore, it takes time for students to receive others’ comments to their posts about GRs.

Harada (2015) suggested the possibility of combining ER and discussion using a learning management system (LMS) by implementing ER lessons in which students read GRs as a PDF file on Moodle in class and post their comments to a Moodle forum. The merit of this method is to enable students to receive their peers’ comments to their posts in real time because students write them on Moodle during class. However, it is impossible to conduct this type of lesson if the institution does not use LMS.

This study implements a Japanese ER program for international students studying at a Japanese university using Facebook as a tool to organize a reading community. Following the implementation results, the author discusses the following hypotheses:

- It is possible to use Facebook to build a reading community outside the ER classroom.

- It is possible to use Facebook to organize discussion about GRs outside the ER classroom.

Method

Currently, over 100 Japanese graded readers exist; with five levels between beginner and intermediate levels, there are about 10 - 30 books per level. Considering the number of students, their Japanese levels, and their varied interests, we thought that more books were needed for this study. Therefore, we prepared comic books, picture books, and children books for this class. A total number of 264 books were selected; Table 1 shows the breakdown of these books based on their category. The students were also encouraged to read other books as long as the books’ levels were appropriate.

Participants

Nineteen international students studying at a Japanese university participated in the research. There were 15 freshmen (9 Chinese, 5 Korean, 1 Malaysian) and four sophomores (2 Chinese, 1 Korean, 1 Singaporean). Freshmen and sophomores take Japanese as a compulsory course twice a week (90 min ×30 sessions/semester). For freshmen, the goal of the course is to acquire a strategy for studying at university, focusing mainly on academic writing. A goal for sophomores is to be able to construct a convincing argument. As both courses also focus on oral expression and rely on classroom discussions, ER was embedded in them in a blended way. As both courses included ER classes in the previous term, it was the second time that ER had been used in these courses. The ER lesson took place over two individual sessions. A 1-week interval between the first and second session allowed for preparation time. As a noncredit addition to an existing reading course, the ER lesson was treated as part of the Japanese language course, but GR contents were not included in the course test.

To understand participants’ needs and abilities, the Simple Performance-Oriented Test (SPOT), vocabulary assessment, and prequestionnaire were given to the participants in the first session. SPOT was used to assess grammar (Kobayashi, 2003). A previous Japanese language proficiency test was used to assess vocabulary. The prequestionnaire asked about the student’s time spent learning Japanese and whether he or she had used social networking services (SNS). To those students who answered “yes,” the prequestionnaire used multiple-choice questions to ask about the kind of SNS used, device used, frequency of use per week, with whom, language used, and for what purpose. The prequestionnaire included open-ended questions, such as “In what kind of situations do you think that SNS is useful?” and “How can we ensure that SNS will be useful for ER lessons?” The students’ average period of learning Japanese was 2 years, with the shortest being 1 year, and the longest 5 years. If the period after university entrance is counted, sophomores study Japanese for 1 year longer than freshmen do.

Reading Materials

JGR SAKURA is a small library of Japanese GRs divided into eight levels from A to H. Level D in this series targets beginner to intermediate learners and was used in this research. The author selected Kaeru (2474 characters) and Sen-nin (17,591 characters), which are short stories in level D, as assignments for this ER lesson because all participants read and discuss the same GRs. The two JGR SAKURA titles were made available as PDF files in the library e-learning system for this ER lesson.

ER Assignments

The author explained to participants the purpose of ER, how it differs from intensive reading, and how to read GRs and undertake the reading assignment steps (1) to (3) described below. In the previous semester, all participants wrote their reviews on forms (an A4-sized page). The review form included questions, such as “How do you rate the book?” and “Which is the most interesting part, and why?” In this semester, Facebook replaced the forms in step (3). Once their assignments were prepared, participants took part in step (4). However, step (4) is outside the scope of this paper.

- The author creates a private group on Facebook and invites participants to join the group. The author adds PDF files on Facebook and on the e-learning system (Nakano, 2013).

- Participants read the assignments (PDF) on their devices. The assigned books are Kaeru for the first session, and Sen-nin for the second. The topic for discussion in the classroom is “If you were the character in the story, what would you have done?”

- Participants post their comments about the assignments to Facebook by the day of the ER lesson. Participants who do not have a Facebook account are given a form to write their review. They are then asked to bring the form to class for each session. Participants who read beyond the assignments may also post their comments to Facebook or present their reviews to the classmates.

- In the ER lesson, groups of three–four participants are formed to discuss GR texts according to the review form. One person from each group presents what they have discussed to the wider group.

Results

Prequestionnaire

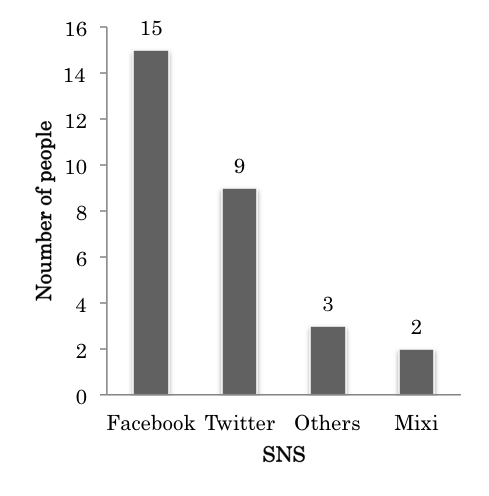

The results of the prequestionnaire found that 16 of the 19 participants had used SNS (84% of all participants). Facebook was ranked first of all SNS used by participants (Figure 1).

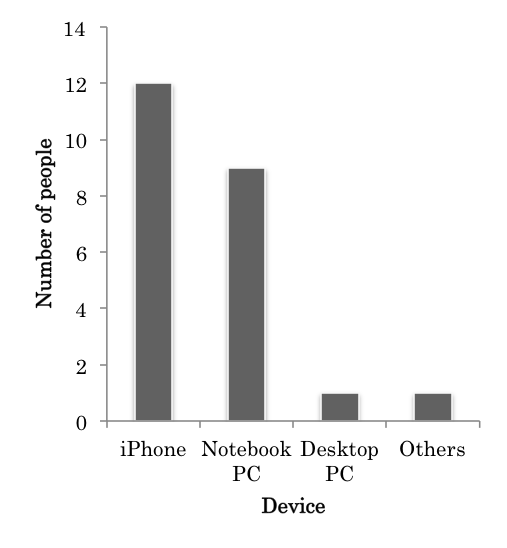

Smartphones were used slightly more frequently than PCs when participants used SNS (Figure 2).

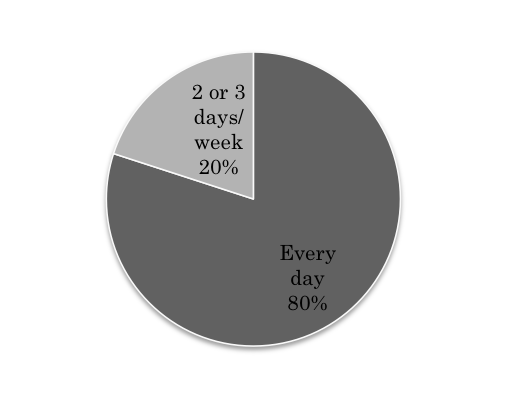

Eighty percent of participants used SNS every day and other participants used SNS as frequently as 2 or 3 days per week (Figure 3).

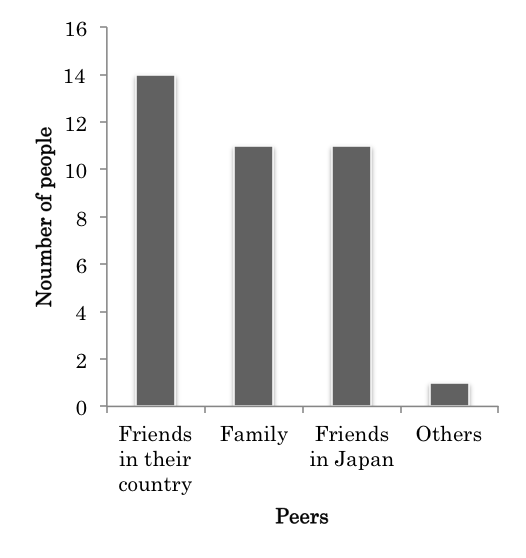

Participants used SNS mostly with “friends in their country,” followed by “family” and “friends in Japan.” Sixty-eight percent used SNS to communicate with “friends in their country” and “family.” That is, participants used SNS to communicate with others who live in their home countries and used their first language (Figure 4).

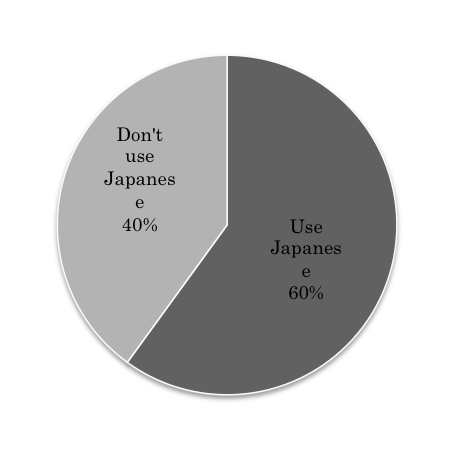

This result is reflected in the language used (Figure 5).

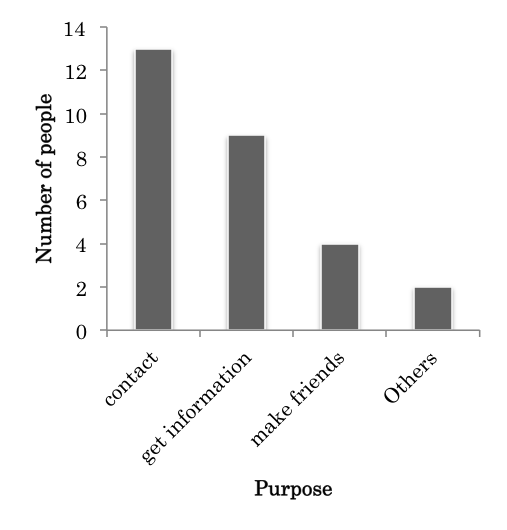

Sixty percent of participants used both their first language and Japanese, and the remainder used only their first language. Participants ranked “contact” first in their purpose of using SNS, followed by “get information” (Figure 6).

The answers to the question “In what kind of situations do you think that SNS is useful?” were as follows:

- “We could know what’s going on with friends and family without making contact with them.”

- “It is convenient to look at photographs, gossip, and keep a diary.”

- “It is convenient to make contact with the course instructor.”

- “It can be used at any time and place. The cost is economical, especially when in a foreign country.”

- “I do not feel that it is so convenient.”

The answers to the question “How can we ensure that SNS will be useful for ER lessons?” were as follows:

- “It is better to organize a private Facebook group and upload photographs to the group.”

- “It is better to use a PC for lessons.”

- “It is better to use an app.”

- “I do not know whether we would enjoy ER lessons, but the frequent use of SNS would accustom us to them.”

Posting Comments about GRs

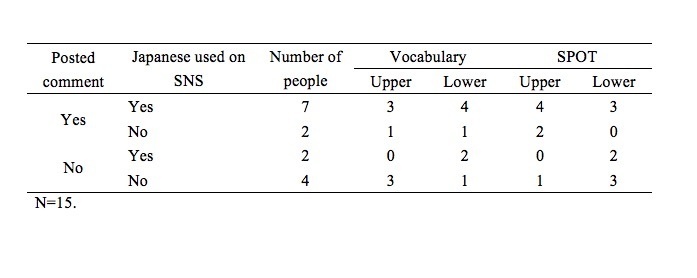

Fifteen of the 19 participants had been using Facebook. Of these 15 participants, 9 participants (60%) wrote their comments about the assignments on Facebook. The 15 participants were divided into upper (7 participants) and lower (8 participants) groups based on their pretest scores, and were divided into two categories by asking whether participants usually used Japanese on SNS (Table 1).

Table 1. Relationship between Comment Posts and the Use of Japanese in SNS

Seven participants usually used Japanese on SNS, and two of the participants who had not used Japanese on SNS before, wrote their comments on Facebook. The rate of participants who usually used Japanese on SNS was higher than that of participants who had not used Japanese on SNS. There was no significant difference between the upper and lower groups in their vocabulary pretest scores. However, the rate of participants who wrote their comments on Facebook was slightly higher in the upper SPOT group. Six participants in the upper group wrote their comments on Facebook compared with three from the lower group.

Comments on Other Participants’ Posts

The author posted a response to each post made by participants. One participant replied to the author’s response and continued the discussion. Participants did not comment on each others’ posts. Finally, the author made a post about the GR, and one participant commented on it and continued the discussion.

Seeing Other Participants’ Comments and Using “Like”

All Facebook comments were seen by everyone. Some participants also used Facebook’s “Like” function on their peers’ comments.

Discussion and Conclusion

Participants can freely register to use SNS, which is a positive quality of the SNS environment. Although some participants in this study who did not have a Facebook account were asked by the author to write their GR comments on paper sheets, there was no problem using SNS for postreading activities.

We discussed whether it is possible to use Facebook to build a reading community and organize discussions about GRs outside the ER classroom. The implementation results showed that 60% of participants who used Facebook in the activity made posts about GRs and all posts were seen by all participants using Facebook. In this survey, however, the discussion did not extend to a stage in which participants responded to each other. This may be because the author did not instruct participants to do so. Posting on Facebook replaced writing a review of the GR on a paper form which is mentioned above.

Another reason may be because there are several steps in participating in a SNS discussion; that is, reading other person’s posts, posting “Like,” and writing responses or debating about other people’s comments. No participant was excluded from any step of the discussion, and this result shows that all participants joined the reading community. During classroom discussions, there were differences in quantity and quality of speech between learners who were more proficient in Japanese and those less proficient. For less proficient learners, they had positive attitude to join the community of readers. The fact that every student read posts, with some of them also either posting or liking, may be interpreted as a wiliness to use Facebook to build a reading community. The results revealed that 40% of participants who had used Facebook, but did not post comments, tended not to use Japanese on SNS and scored poorly in their grammar assessment because of their lack of Japanese language skills. It was difficult for those participants to write comments in Japanese at that point.

From these study results and considering that participants in the reading community read their peers’ comments, the author concluded that Facebook could be used to build a reading community outside the ER classroom. These results suggest that learners can discuss GRs on Facebook outside the ER classes. At institutions where LMS has not been introduced, Facebook could be used instead to organize postreading activities outside the classroom.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of this study is that the author did not survey whether participants were stimulated to read by observing other learners’ progress. However, the author did confirm that Facebook could possibly be used to organize postreading activities because all participants read each other’s Facebook comments.

A reading community outside the classroom in which learners can know that other learners are also reading would be effective, if it motivates learners who have not yet read the assignment to begin reading. ER is essentially autonomous learning, and if supported by a community, for example on Facebook, learners may be encouraged to continue ER. Future studies are exploring methods of creating an online learner community to support ER learners who are reading JGR SAKURA.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K02650.

References

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harada, T. (2015). LMS (Moodle) o riyousihta tadoku no kanousei: Tadokugo no forum toukoubun o chushin ni. Oberlin Gengokyouiku Ronso, 11, 109-125.

Kobayashi, N. (2003). SPOT: Measuring Japanese language ability. The 31st annual meeting of the Behaviormetric Society of Japan, 110–113.

Kuga, N., Nakano, T., Cong, Y., Jung, J. & Mayekawa, S. (2006). A study of social facilitation effect on e-Learning. Proceedings of e-Learn 2006, 1659-1664.

Kumada, M. (2012). Free reading: The class which the students have the leadership in reading. Waseda Practical Studies in Japanese Language Education,71–83.

Matsuoka, H. (1990). Ginobetsu no shido. In The Society for Teaching Japanese as a Foreign Language (Ed.), Nihongo Kyoiku Handbook (pp. 72-74). Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

Nakano, T. (2013). Introduction of extensive reading using electronic teaching materials. Shobi University Sogoseisaku Ronshu, 17, 137–144.

Reynolds, B., Harada, T., Yamagata, M. & Miyazaki, T. (2003). Towards a framework for Japanese graded readers: Initial research findings. Papers of the Japanese Language Teaching Association in honor of Professor Fumiko KOIDE, 11, 23–40.