Chapter One: Effects of Extensive Reading on Japanese Language Learning

Eri Banno & Rie Kuroe

Okayama University, Japan

Abstract

This paper reports the implementation of extensive reading in a Japanese as a Second Language class and discusses extensive reading’s effects for Japanese language learning. The extensive reading class was offered in a Japanese university to 32 intermediate to advanced Japanese language learners. The results of questionnaires of two types indicated that by the end of the course, the students thought that they could improve their reading ability, they changed their reading strategy, and they began to desire reading more in Japanese. The students’ comments also supported these findings. These results therefore indicate that extensive reading can be a powerful method for Japanese as a Second Language learning.

Introduction

Extensive reading has been widely incorporated in second or foreign language classrooms. However, few extensive reading studies explore the method’s potential in Japanese as a Second or Foreign Language (JSL/JFL) contexts. This paper reports on the implementation of extensive reading in JSL classes at a Japanese university and discusses extensive reading’s effects for Japanese language learning. First, we will describe the extensive reading class in our university Japanese course. We will then report the method and results of the questionnaire conducted in the extensive reading class. Finally, from the study’s results, we will discuss the effects of extensive reading.

Extensive Reading for JSL/JSL Learners

Extensive reading is an approach where people read quickly and enjoyably with adequate comprehension without using a dictionary (Extensive Reading Foundation, 2011). To implement extensive reading, Day and Bamford (2002) have suggested the “Top Ten Principles for Teaching Extensive Reading.”

- The reading material is easy.

- A variety of reading material on a wide range of topics must be available.

- Learners choose what they want to read.

- Learners read as much as possible.

- The purpose of reading is usually related to pleasure, information and general understanding.

- Reading is its own reward.

- Reading speed is usually faster rather than slower.

- Reading is individual and silent.

- Teachers orient and guide their students.

- The teacher is a role modal of a reader.

In JSL/JFL contexts, teachers can implement extensive reading in their classrooms as Japanese graded readers have become available since 2006. However, extensive reading is still uncommon in JSL/JFL classrooms and few articles report on the implementation of this technique. Hitotsugi and Day (2004) collected 266 Japanese children’s books and asked elementary Japanese learners to read outside class. In their survey, they found an increase in students who responded positively toward studying Japanese. Interviews and surveys from other studies (Kawana, 2012; Matsui, Mikami, & Kanayama, 2012; Ninomiya & Kawakami, 2012; Ninomiya, 2013) also showed the positive effects of extensive reading when students freely read graded readers in class.

Extensive Reading Class in the Japanese Language Course

Overview

In 2013, the extensive reading class was implemented in a Japanese language course at the target university. It was an elective class so that students’ participation was voluntarily. The classes were 90-minutes long and were held for 15 weeks. The participating students’ levels ranged from pre-intermediate to advanced.

The class’ objectives are to help students: (1) enjoy reading in Japanese, (2) read without translation, (3) read faster, (4) increase receptive vocabulary, and (5) read habitually. In order to attain these goals, we asked students to read easy books, skip/guess what they do not understand, focus on the overall meaning, not read slowly, and select another book if the current one is too difficult.

Furthermore, the course’s requirements include (1) weekly book reports and comment sheets, (2) three poster presentations, (3) number of the books they read, and (4) class attendance and participation. In the book report, students wrote on whether the books were interesting, how difficult the books were, and short summary of the books. For the comment sheet, students wrote about their thoughts on their reading ability, such as their reading speed and problems. In the poster presentations, students created a poster of their favorite book and used it to inform other students about the book in the class. Furthermore, the number of books students read was also included in the grade. However, as we intended the students to read both extensively and enjoyably, the number of books read only accounted for 10% of the final grade. Students who read over 60 books were awarded full marks; the points decreased as the number of the books read decreased.

Classes typically began with the teacher introducing some books to the students, who then quietly read their self-selected books. While the students read, the teacher talked to each student individually to ask whether they have any problems or what they thought of the books they read. Approximately 10 minutes before the end of class, students form small groups to discuss the most interesting books they read that day.

Materials

Currently, over 100 Japanese graded readers exist; with five levels between beginner and intermediate levels, there are about 10 - 30 books per level. Considering the number of students, their Japanese levels, and their varied interests, we thought that more books were needed for this study. Therefore, we prepared comic books, picture books, and children books for this class. A total number of 264 books were selected; Table 1 shows the breakdown of these books based on their category. The students were also encouraged to read other books as long as the books’ levels were appropriate.

Table 1. Books for the Extensive Reading Class

| Category | Number of Books |

| Graded Readers | 101 |

| Comics | 61 |

| Picture Books | 44 |

| Books for Elementary School Students | 58 |

| Total | 264 |

Research Questions

This study attempts to answer the following research questions:

1.Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their language abilities? 2.Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their reading style? 3.Does extensive reading change students’ attitude toward reading?

Method

**Participants **

There were 32 students participating in the extensive reading class at the target university. Their Japanese levels ranged from pre-intermediate to advanced. Of the 32, 11 students were from the United States, five students from China, three students each from France, Germany, and Thailand, two students from Korea, one student each from Lithuania, Philippines, Russia, Serbia, and Taiwan. Furthermore, 31 of the 32 participants were exchange students who have been in Japan for one semester or just arrived in the country.

Data

Questionnaire A (pretest and posttest)

Questionnaire A was conducted twice (in the first and last class). The questionnaire aimed to identify changes in students’ perceptions of their Japanese language ability, reading styles, and attitudes toward reading. The question types include questions on students’ Japanese language ability (5 questions), strategy or habit (5 questions), anxiety (4 questions) and comfort (5 questions). The questions on strategy or habit were based on Hitotsugi and Day (2004), and the questions on anxiety and comfort were taken from Yamashita (2013). The questionnaire was written both in Japanese and English. Students responded to the questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree.

Questionnaire B (posttest)

Questionnaire B was conducted in the final class. This questionnaire elicited student feedback on the class. Students were also asked whether they thought their language ability improved. The questionnaire was again written both in Japanese and English. Students again responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “5” (strongly agree) to “1” (strongly disagree).

Results

Questionnaire A (pretest and posttest)

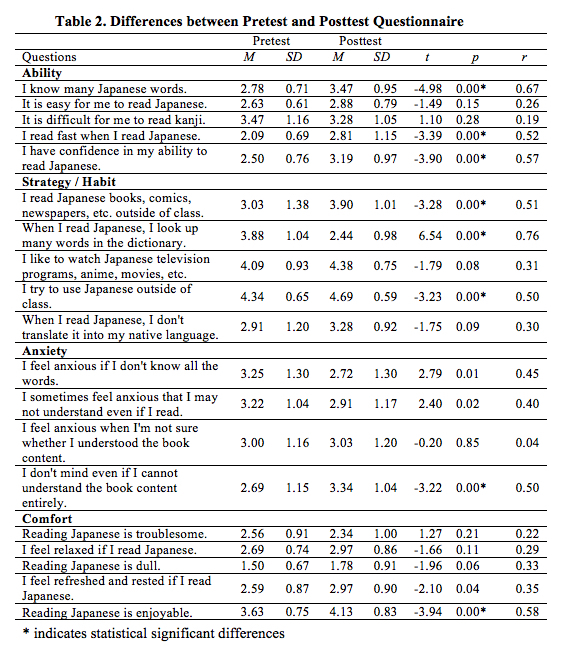

Table 2 shows the difference between the pre- and posttest of Questionnaire A. The difference was analyzed using the paired t-tests. Furthermore, as multiple t-tests were conducted, the alpha level was adjusted using the Holm’s method.

The three “Ability” questions were found to be statistically significant between the pre- and posttest. This indicates that students perceived an increase in vocabulary, reading speed, and reading ability by the end of the course.

Additionally, the three “Strategy or Habit” questions were also found to be statistically significant. The question “When I read Japanese, I look up many words in the dictionary” was significantly lower in the posttest, indicating that students relied on dictionaries less by the end of the course. On the other hand, the question “I read Japanese books, comics, newspapers, etc. outside of class” received significantly higher scores in the posttest. This suggests that by the end of the course, students were reading more outside of class. The question “I try to use Japanese outside of class” was also significantly higher in the posttest. It must be noted that these differences might be due to the factors besides extensive reading. Most of the participants have lived in Japan for less than a year, thus these differences may have emerged as they adjusted to living in Japan and made more Japanese friends. Lastly, while the question “When I read Japanese, I don’t translate it into my native language” scored higher in posttest, it was not statistically significant.

Only one of the “Anxiety” questions was statistically significant (i.e., “I don’t mind even if I cannot understand the book content entirely”). The two questions, “I feel anxious if I don’t know all the words” and “I sometimes feel anxious that I may not understand even if I read” were not statistically significant but had very low alpha levels. This indicates that students feel less anxious about not understanding every word or content by the end of the course.

The “Comfort” question on “Reading Japanese is enjoyable” was significantly higher in the posttest, indicating that students enjoyed reading more by the end of the course.

Questionnaire B (posttest)

In the final class, students were asked how they perceived extensive reading. Table 3 shows the mean scores and standard deviations of the questions on extensive reading. All the questions received high mean scores (i.e., above 4.0). More specifically, every question other than “I came to like reading” had very high mean scores.

Table 3: Questions on Extensive Reading

| Questions | M | SD |

| Extensive reading was interesting. | 4.47 | 0.66 |

| Extensive reading is effective for Japanese language learning. | 4.56 | 0.66 |

| I came to like reading. | 4.09 | 0.95 |

| I want to continue extensive reading in Japanese. | 4.53 | 0.66 |

The students were also asked if they thought their Japanese language abilities had improved through extensive reading. Table 4 shows the mean and standard deviations of the questions on students’ language ability. Only the questions on listening, writing, speaking had lower mean scores, which was expected for a reading class.

Table 4. Questions on Language Ability

| Questions | M | SD |

| My reading speed became faster. | 4.22 | 0.82 |

| I could learn kanji. | 4.19 | 0.68 |

| I could learn vocabulary. | 4.19 | 0.63 |

| I could improve my reading skills. | 4.44 | 0.61 |

| I could improve my listening skills. | 2.78 | 1.22 |

| I could improve my writing skills. | 3.38 | 0.70 |

| I could improve my speaking skills. | 3.19 | 0.81 |

Discussion

Research question 1 asked “Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their language abilities?” As shown in Table 3, the mean score for “Extensive reading is effective for Japanese language learning” was very high, indicating that students strongly felt that extensive reading effectively improved their Japanese language ability. Additionally, the results of Questionnaire A show that students believe they have improved vocabulary, reading speed, and reading confidence. Furthermore, the results of Questionnaire B show that the students think that they could improve their reading skills, their reading speed became faster, and they could learn kanji and vocabulary. These results indicate that by reading extensively the students think that aspects of their reading ability such as reading speed, vocabulary, and kanji knowledge improved.

On a comment sheet for the final class, Student A from Thailand wrote about changes in her reading speed and extensive reading’s usefulness: “My reading speed is better. I don’t use the dictionary a lot when I find unknown words now. By reading Japanese books I can learn new words and practice grammar, so it is very useful.”

Research question 2 asked, “Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their reading style?” The student’ comment above demonstrates her change in dictionary use when encountering unknown words. Additionally, Questionnaire A’s results show that students looked up words less frequently when reading by the end of the course. These results suggest that students changed their dictionary-use strategy when reading,

On a comment sheet, Student A wrote about the advantages of reading without a dictionary:

When I see unknown words, it is better not to look at a dictionary. When I look at a dictionary, I can’t follow the content and the book becomes uninteresting. If you want to know the meaning, it is OK to look at a dictionary once or twice. The more I read, the better I like reading.

This student believes that constantly referring to a dictionary restricts her understanding of the books and her overall enjoyment. The last sentence from the above excerpt also suggests the student increased reading enjoyment through reading extensively.

On the other hand, no statistical difference was found in “When I read Japanese, I don’t translate it into my native language.” Although the reason for this result is unclear, the results may due to how the rating scale was inappropriate for this question; it would be more appropriate to ask them to choose from “always” to “never” rather than “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Research question 3 asked, “Does extensive reading change students’ attitude toward reading?” The results of Questionnaire A show decreased student anxiety toward not understanding everything when reading by the end of the course.

Student B from Korea wrote that her fear for reading unknown words changed during the course. In the 11th week, this student wrote: “I noticed my reading has changed. I felt uneasy when I saw unknown words, but not now.” By week 15, the same student stated the following: “My reading speed is faster and I don’t have fear for reading, and I am really happy. I am going to read various books during summer vacation.”

The results of Questionnaire A also show that students think reading Japanese is enjoyable and that they increasingly read outside of class. Questionnaire B also indicates that students think extensive reading is interesting and want to continue reading extensively in Japanese.

Student C from China commented that reading easy books is interesting and enjoyable: “I first wanted to challenge difficult books, but now I am enjoying reading. When I read easy books, I can learn more.” Other students mentioned their desire to continue reading even after the course finishes. One of them was Student D from Thailand.

I read various books. My reading speed is faster and I always enjoyed reading. I promise that I will not quit reading even after the class is over. I want to read many books from now on.

By reading easy books, the students felt less anxious and found reading in Japanese enjoyable. This feeling of enjoyment seems to encourage their desire to read more in Japanese.

Conclusion

In this paper, we first described the Japanese extensive reading class at our target university. We then reported the method and results of the questionnaire conducted in this class. Finally, from the study’s results, we discussed the effects of extensive reading. The results of the study indicate that at the end of the course, students perceived improved reading ability, changed reading strategy, and increased desire for reading in Japanese. By reading many easy books that interest them, and trying to read fast without looking at a dictionary, the students notice their improvement in their reading skills as well as changes in their reading styles. The students’ comments also support these findings. These results suggest that extensive reading can be a powerful method for language learning.

References

Day, R. & Bamford, J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14, 136–141.

Extensive Reading Foundation (2011). The Extensive Reading Foundation’s Guide to Extensive Reading. Retrieved from http://erfoundation.org/ERF_Guide.pdf.

Hitotsugi, I. & Day, R. (2004). Extensive reading in Japanese. Reading in a Foreign Language, 16(1), 20–39.

Kawana, K. (2012). Jookyuu gakushuusha o taishoo to shita tadoku jugyoo – kaki Nihongo kyooiku C7 crasu ni okeru jissen [Extensive reading for advanced Japanese learners: Implementation in summer Japanese class C7]. ICU Japanese Language Education Research, 9, 61-73.

Matsui, S., Mikami, K., & Kanayama, Y. (2012). Shokyuu, chuukyuu Nihongo koosu ni okeru tadoku jugyoo no jissen hookoku [Practical reports of implementation of extensive reading in the beginner and intermediate Japanese language course]. ICU Japanese Language Education Research, 9, 47-59.

Ninomiya, R. & Kawakami, M. (2012). Tadoku jugyoo ga jooimen ni oyobosu eikyoo – dooki zuke no hoji, sokusin ni shooten o atete [Effects of extensive reading on JSL learners’ motivation]. Journal of Global Education, 3, 53-64.

Ninomiya, R. (2013). Tadoku jugyoo ga shokyuu gakushuusha no naihatuteki dooki zuke ni oyobosu eikyoo [Effects of extensive reading on beginning level learners’ motivation]. Journal of Global Education, 4, 15-29.

Yamashita, J. (2013). Effects of extensive reading on reading attitudes in a foreign language. Reading in Foreign Language, 25(2), 248-263.