Relationships

Lesson content

- What are relationships

- Types of relationships

- Declaring and referencing related objects

- Most common errors

What are relationships

Living things, objects and phenomena in the real world often form relationships. For example, two persons can be in love (the relationship being “in love”), or one person can be a sibling to several persons (“is sibling” relationship). On the other hand, a fuel tank “is part of” a car (also a type of relationship), as well as an inventory item being “a part of” an inventory list. Cars, trucks, motorcycles and vans are all “types of” motorized vehicles (“is type of” relationship) etc.

Classes, as simplified representations of real-world entities, can also form mutual relationships that reflect real ones. Relationships between classes are also just called relationships. Just as objects inherit and use attributes and methods of the class they belong to, they also inherit relationships.

There are two basic types of relationships:

-

Association and its specialized forms:

- Composition - decomposition (“HAS-A” relationship, “PART-OF” relationship)

- Generalization - specialization (“IS-A” relationship, inheritance)

- Usage relationship (“USING” relationship)

Association and its specialized forms (composition-decomposition and generalization-specialization) pertain to structure, as they establish structural links between classes, while the usage relationship pertains to behavior.

Association is the most general form of relationship in which objects of one class have a structural link or relation to objects of another class. Every association is defined through three elements:

- Cardinality

- Navigation (direction)

- Name (role)

Cardinality refers to how many objects of one class can be related to an object of another class. It determines constraints such as: “an order must have exactly one customer” or “a company must have at least one employee.”

Cardinality doesn’t have to be a single number — it can be a range, which means there is a lower and upper bound of cardinality. The most commonly used cardinalities are:

| Cardinality | Example |

|---|---|

| 1..1 (or just 1) | An order must have exactly one customer |

| 0..1 | A stock market client may have an exclusive broker, but doesn’t have to |

| 0..* (or just *) | A person may own one or more cars, or none |

| 1..* | A company must have at least one employee, but may have more |

Navigation (direction) of an association refers to which class it is directed from and to. For example, the association “drives” goes from the class Person to the class Car. Based on this, associations can be unidirectional or bidirectional, with the latter being visible from both directions.

Each association can also have a name (role) that describes the relationship it represents. Unidirectional associations can have one name, while bidirectional ones can have two names based on the direction. For example, the association between the class Company and the class Employee might be:

- “employs” from Company to Employee

- “is employed by” from Employee to Company

In Java, associations are usually implemented as ordinary class attributes, but the type of the attribute is the class itself — by referencing the class name. In general, the implementation depends on the cardinality. For example, many-to-many relationships are often implemented via an additional class. Graphically, associations are shown as solid lines between classes, with possible cardinality and association name indicated. If unidirectional, the line may end with an arrow showing the direction.

Example 1

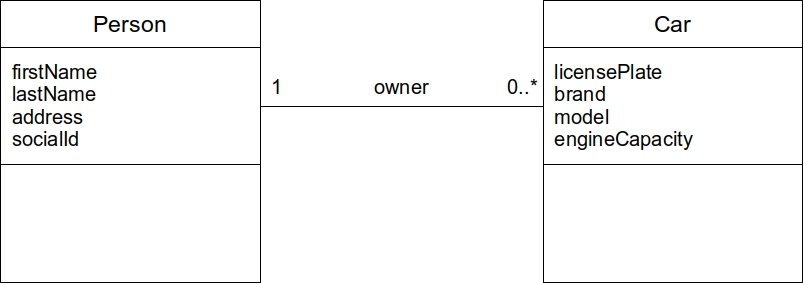

An example of an association is the relationship between Car and Person classes, where a person is the owner of the vehicle (Figure 21). This is a bidirectional association (no arrows).

Pay attention to the cardinality: next to the Car class is “0..*”, meaning a person can own many cars or none. The other direction shows “1”, meaning each car has exactly one owner.

This association has one name (“owner”), but could be written with two names:

- “is owner” (from Person to Car)

- “has owner” (from Car to Person)

Java implementation:

1 class Car {

2

3 String brand;

4 String model;

5 String licensePlate;

6 int engineCapacity;

7

8 // Associations are implemented as class attributes.

9 // The type of the attribute is the name of the second class

10 // from the association. Here, the attribute owner is the

11 // object of the class of Person.

12 Person owner;

13

14 }

1 class Person {

2 String firstName;

3

4 String lastName;

5

6 String address;

7

8 String socialId;

9 }

- Class Person has only basic attributes.

- Class Car includes basic attributes plus an attribute owner of type Person:

1 Person owner;

This implementation allows cardinality of 0 or 1, because if owner is not initialized, its value is null. To enforce exact cardinality of 1, use a constructor that either:

- Requires an owner as a parameter

- Or initializes the owner within the constructor

It is important to note that associations are implemented as class attributes, but the name of the second class is listed as the attribute type.

Example 2

Same relationship, but implemented differently:

1 class Car2 {

2

3 String brand;

4 String model;

5 String licensePlate;

6 int engineCapacity;

7

8 }

1 class Person2 {

2 String firstName;

3

4 String lastName;

5

6 String address;

7

8 String socialId;

9

10 // A person can be the owner of one or more cars.

11 // Therefore, in addition to the name of the Car2 class,

12 // the attribute owner has angular brackets ("[]") to indicate

13 // that there can be more objects (specifically, an array of

14 // Car2 objects).

15 Car2[] owner;

16 }

- The Car2 class would contain only “regular” attributes

- The Person2 class would be a class that contains both “regular” attributes and the owner attribute, which represents the relationship. In this case, the relationship involves a higher cardinality (a person can own multiple cars)

The attribute owner is an array of Car2 objects in the Person2 class (to reflect one person owning multiple cars).

1 Car2[] owner;

The implementation of a relationship when the cardinality is greater than one is done using appropriate data structures that can hold multiple objects. Some of these data structures are: arrays, lists, maps, etc. Arrays and lists are covered in detail in the following lessons and will not be explained here.

Example 3

Finally, this same relationship between the classes Person and Car (Figure 21) can also be implemented in a third way, by adding the owner relation as an attribute in both classes (merging the previous two solutions). In this way, it becomes a bidirectional implemented relationship.

The third variant of implementing this association would look like this:

1 class Car3 {

2

3 String brand;

4 String model;

5 String licensePlate;

6 int engineCapacity;

7

8 Person3 owner;

9

10 }

1 class Person3 {

2 String firstName;

3

4 String lastName;

5

6 String address;

7

8 String socialId;

9

10 Car3[] owner;

11 }

- The Car3 class would contain only “regular” attributes and the owner attribute that represents the relation

- The Person3 class would contain both “regular” attributes and the owner attribute that represents the relation. In this case, the relation encompasses a greater cardinality (a person can own multiple cars)

The question arises: Which of these three implementations of the given association is the best? The answer depends on the specific situation, but for simplicity, perhaps in this case, the first variant (from Example 1) is the best, where the association is such that the connection is made from the Car class and each car contains data about its owner (Person class). So, even though the association from Figure 21 is bidirectional, for simplicity, it does not have to be implemented as bidirectional and can be implemented only in one class.

Declaring and referencing related objects

Calling an object through the association is done in a similar way to calling a regular attribute, with the difference that the object needs to be initialized before its first use – just like when using other objects.

1 c.owner = new Person();

2 c.owner.name = "John";

Example 4

Write a class TestCar that in the main method creates an object of the Car class (from Example 1) with the brand “Ford”, model “Focus”, license plate “W123-456”, and engine capacity 1799.

Set the owner of this car to be Peter Smith, social ID 710128, who lives at Elm Street 27. Use the Person class (from Example 1).

The TestCar class would look like this:

1 class TestCar {

2

3 public static void main(String[] args) {

4 Car c = new Car();

5

6 c.brand = "Ford";

7 c.model = "Focus";

8 c.licensePlate = "W123-456";

9 c.engineCapacity = 1799;

10

11 // Attribute owner is an object

12 // so it must be initialized before use

13 c.owner = new Person();

14

15 //Owners attributes (Person attributes)

16 // can be accessed through the Car objects

17 // name (c) followed by the owner attribute

18 // name (owner) all separated by dots.

19 c.owner.firstName = "Peter";

20 c.owner.lastName = "Smith";

21 c.owner.socialId = "710128";

22 c.owner.address = "Elm street 27";

23 }

24

25 }

Before using the owner attribute, it is necessary to initialize the object of the Person class that represents the car owner:

1 c.owner = new Person();

The attributes of the Person class object, which is the car owner, can be accessed indirectly — first by calling the Car class object (c), and then calling the owner attribute. Since the owner is also an object, it has its attributes which can further be accessed by their name (i.e. address). Each element in the call must be separated with a dot.

1 Object name (c)

2 | Attribute name (owner), which is also an object of the Person class

3 | | Attribute name (address)

4 | | |

5 c.owner.address = "Elm street 27";

Composition - Decomposition represents a special type of association in which an object of one class, as a component, contains one or more objects of another class. There are two types of composition-decomposition relations.

If the contained object (or objects) cannot exist independently of the object that contains it, it is composition, and if it can exist independently, it is aggregation. In composition, when the object that contains other objects is deleted, those objects are also deleted. In aggregation, this is not the case.

The composition-decomposition relationship is graphically represented by a line with a diamond at one end. If the diamond is filled, it indicates composition; if it is empty, it indicates aggregation. Composition-decomposition can have a name, and the cardinality is written only on one side because the other side is always 1.

Composition-decomposition is implemented in the same way as a regular association - via class attributes. The only difference is in how the association is interpreted.

Example 5

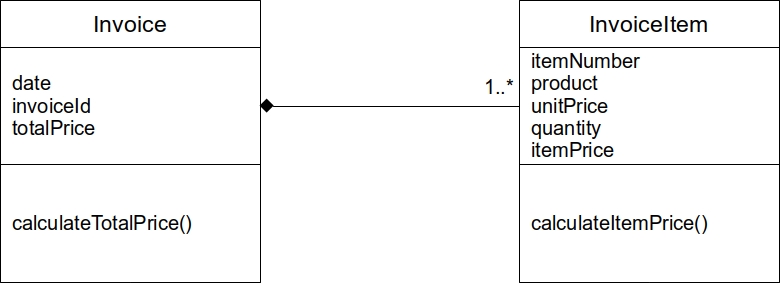

A commonly cited example to describe the composition relation is the relationship between the classes Invoice and InvoiceItem (Figure 22).

Each invoice contains one or more items (the lower cardinality is 1, and the upper cardinality is many), and each item belongs to exactly one invoice (both the lower and upper cardinality are always 1, so they are not even written).

It would make no sense to have invoice items that do not belong to any invoice or items that belong to several invoices at once. Also, when an invoice is deleted, all its items are deleted as well.

*The implementation of this composition could look like this (with similar alternative implementations as for Example 1, Example 2, and Example 3):

1 class InvoiceItem {

2

3 int itemNumber;

4

5 String product;

6

7 double unitPrice;

8

9 double quantity;

10

11 double itemPrice;

12

13 // Calculates the item price by

14 // multiplying unitPrice with quantity

15 void calculateItemPrice(){

16 itemPrice = unitPrice * quantity;

17 }

18

19 }

1 class Invoice {

2 // Special Java classes are used for dates,

3 // but String is put here for simplicity

4 String date;

5

6 int invoiceId;

7

8 double totalPrice;

9

10 InvoiceItem[] items;

11

12 void calculateTotalPrice(){

13 // some code which sums all individual item prices from

14 // the "items" array

15 }

16 }

Invoice item contains the data for a single invoice item and has a method that calculates how much that single item costs - calculateItemPrice (e.g., two loaves of bread costing 54 cents each would total 108 cents). The invoice date is set to be of type String, but in Java, special classes are used for this, which are covered in later lessons.

Invoice contains a composition to multiple invoice items, implemented as an attribute called items (an arbitrary name, the composition name is not specified in Figure 22) which is an array of InvoiceItem objects:

1 InvoiceItem[] items;

The method calculateTotalPrice should loop through the array of invoice items and add up the individual amounts of each item, then enter the total sum into the attribute totalAmount. Since arrays of objects (as a topic) are covered in later lessons, the code for this method is omitted in this example.

Example 6

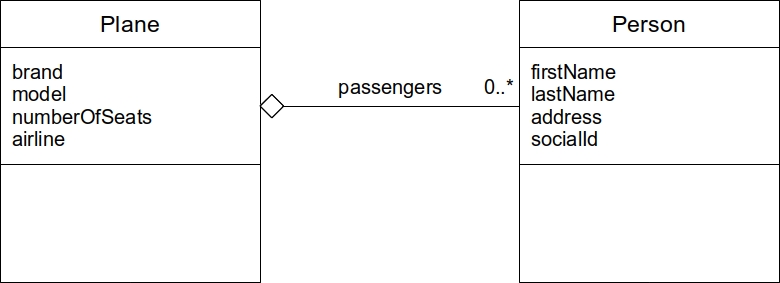

An aggregation relationship can be demonstrated through the relationship between the classes Plane and Person, where the people are passengers on the plane (Figure 23).

Unlike composition, aggregation implies that the aggregated objects can exist independently of the object that contains them. In this case, objects of the Person class can exist as separate entities – completely unrelated to the context of the Plane and its passengers.

For example, an object of the Person class can form an association “owner” with objects of the Car class.

The implementation of this aggregation could look like this (with similar alternative implementations as in Example 1, Example 2, and Example 3):

- Class Person (from Example 1)

- Class Plane

1 class Plane {

2

3 String brand;

4

5 String model;

6

7 int numberOfSeats;

8

9 String airlineName;

10

11 Person[] passengers;

12 }

Class Plane contains an aggregation to multiple Person objects, implemented as an attribute called passengers, which is an array of Person objects:

1 Person[] passengers;

Generalization - Specialization is a type of relationship where one class inherits from another, and is therefore often called inheritance. Inheritance involves taking all attributes and all methods (except private ones) from the superclass (the class being inherited – also called the “parent” class) and transferring them to the subclass (the class that inherits – also called the “child” class). The end result is that the subclass has all the characteristics and (public or protected) behaviors of the superclass, but can also have additional characteristics and behaviors of its own.

Inheritance, public/protected methods, and access levels in general are explained in more detail in later lessons. For now, it’s enough to know that the graphical representation of an inheritance relationship is a directed line with a hollow triangular arrowhead. Cardinality and relationship names are not used with this type of relationship.

Example 7

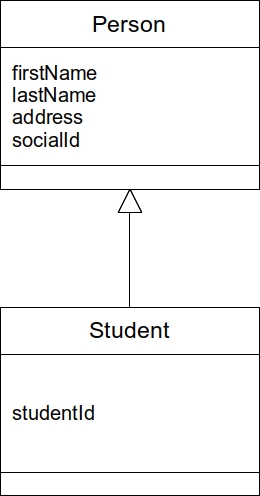

Let’s say the Person class has the attributes: firstName, lastName, address, and socialId. Now, suppose we need to create a Student class that has the same attributes, but also an additional attribute studentId.

In this case, the simplest solution is to make the Student class inherit from the Person class.

The Student class will inherit the attributes firstName, lastName, address and socialId from the Person class, so we only need to add the new attribute studentId (see Figure 24).

The implementation of this inheritance relationship would look like this:

- Person class (from Example 1)

- Student class

1 // The inheritance is declared using

2 // the reserved word extends and stating

3 // the parental class name (superclass)

4 class Student extends Person {

5

6 String studentId;

7

8 }

As you can see, inheritance is marked by the reserved keyword extends, followed by the name of the superclass within the subclass declaration. Specifically, in the Student class declaration, we have:

1 class Student extends Person

In the Student class, there’s no need to redeclare the attributes firstName, lastName, address and socialId — they’re inherited. We only declare the attribute studentId. This avoids duplicating similar or identical code in similar classes. If the Person class had any non-private methods, they would also be inherited by the Student class.

In the main method of the TestStudent class, you can see that an object of the Person class has attributes such as firstName, lastName, address and socialId assigned with values. The Student object, thanks to inheritance, has those same attributes plus the additional studentId attribute, which does not exist in the Person class.

1 class TestStudent {

2

3 public static void main(String[] args) {

4 Person p = new Person();

5

6 p.firstName = "Peter";

7 p.lastName = "Smith";

8 p.address = "Elm street 27";

9 p.socialId = "710322";

10

11 Student s = new Student();

12

13 // The Student class inherits attributes

14 // and methods from the Person class

15 s.firstName = "Mike";

16 s.lastName = "Stone";

17 s.address = "Park street 3";

18 s.socialId = "715065";

19

20 // Student also has an additional attribute studentId

21 // that does not exist in the Person class

22 s.studentId = "123/2023";

23 }

24 }

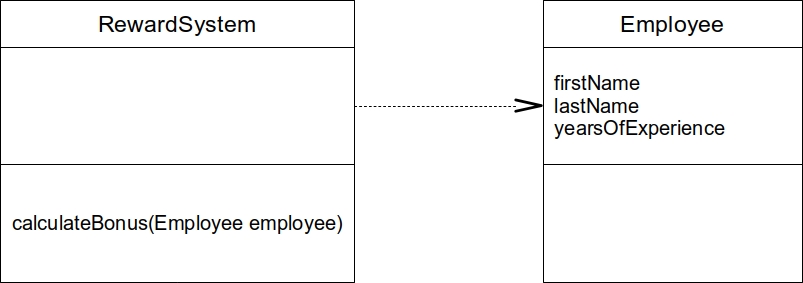

A usage relationship occurs when one class uses an object of another class within one of its methods. It doesn’t matter whether that object is a method parameter, a return value, or simply used within the method body.

This type of relationship typically does not have explicitly defined cardinality or a name, and it is represented graphically with a dashed line directed toward the class that is being used.

Example 8

Create a class Employee with the attributes: firstName, lastName and yearsOfExperience.

Create a class RewardSystem with a static method called calculateBonus. This method receives an object of the Employee class as a parameter and calculates and returns the percentage representing the variable part of the salary using the formula:

1 yearsOfExperience * 1.2

In the figure (Figure 25), you can see how the usage relationship is represented graphically. Like other relationships, this one is shown with a line between classes — but this time it’s dashed and directed: the RewardSystem class uses the Employee class. In usage relationships, names and cardinalities are usually omitted.

The implementation of this usage relationship would look like this:

- Employee class.

- RewardSystem class.

1 class Employee {

2

3 String firstName;

4 String lastName;

5 int yearsOfExperience;

6

7 }

1 class RewardSystem {

2

3 // The method receives the entire Employee object as parameter

4 static double calculateBonus(Employee employee){

5 double bonus;

6 bonus = employee.yearsOfExperience * 1.2;

7 return bonus;

8 }

9 }

In this example, the RewardSystem class uses an Employee object as a parameter in one of its methods. Methods can also return objects as results.

In the main method of the TestEmployee class, you can see that an Employee object named Peter Smith with 30 years of experience is passed entirely to the calculateBonus method.

1 class TestEmployee {

2

3 public static void main(String[] args) {

4 Employee employee1 = new Employee();

5

6 employee1.firstName = "Peter";

7 employee1.lastName = "Smith";

8 employee1.yearsOfExperience = 30;

9

10 double bonus = RewardSystem.calculateBonus(employee1);

11

12 System.out.println("The bonus for "+

13 employee1.firstName + " " +

14 employee1.lastName + " is: " +

15 bonus + "%");

16 }

17 }

Most common errors

Some of the most common syntax errors related to declaring and using relationships include:

- Using an attribute that is an object of another class (i.e., implementing a relationship) without initializing that object. For example:

1 Car c = new Car();

2 c.owner.firstName = "Peter";

Instead of (correct):

1 Car c = new Car();

2 c.owner = new Person();

3 c.owner.firstName= "Peter";