Methods

Lesson Content

- Methods (header, naming convention, body, return value)

- Variables

- The assignment operator (=)

- Method parameters

- Most common errors

Methods (header, naming convention, body, return value)

It has already been stated that classes can have certain behaviors, and these behaviors are expressed in the form of methods. For example, methods in the “Car” class might include: start, stop, turnLeft, turnRight, etc.

Methods actually contain one or more commands that need to be executed as a whole when the method is called. Method definitions in Java are made within the body of the class as follows:

1 return_data_type methodName(...parameters...) {

2 // Method body

3 }

The return data type of the method, its name, and the parameters form the method header (declaration or signature), while all the code written between the curly braces (including the braces themselves) forms the method body (methods block of commands). Like any block of commands, the method body must start wit h an opening curly brace { and end with a closing curly brace }.

Methods define the behavior of the class. In addition to performing a task, a method may also return a value as a result of its execution (methods’ return value). For example, the “add” method of a “Calculator” class could return a number representing the result of an addition.

On the other hand, some methods do not have a return value. An example of such a method would be the “printName” method of the “Person” class, which simply prints the person’s name on the screen. When a method does not return any value, the return data type is void, and when it returns something, the return data type can be any simple or complex data type (int, double, char, boolean, String, LocalDateTime or any class…).

A method can have at most one return value.

The Java naming convention states that, method names are written the same way as attribute names. So, the first word starts with a lowercase letter, and if there are multiple words, the remaining ones start with an uppercase letter, i.e.:

- add

- subtract

- printName

- convertCurrency, etc.

Finally, methods can also have input values - parameters. Parameters represent the values that need to be passed to a method so it can execute correctly. For example, the “add” method of the “Calculator” class might have two numbers as parameters that need to be added. If the method has no parameters, the space between the parentheses is left empty (only “()” is written). Parameters will be explained in more detail later.

Example 1

Create the TelevisionSet class. This class should have:

A volume attribute, which is an integer representing the current volume of the television. The initial value of this attribute is 0 (the volume is turned off).

A currentChannel attribute, representing the channel currently being shown on the television (e.g., channel 5 is on). The initial value of this attribute is 1.

An isOn attribute, indicating whether the television is turned on or off (TRUE if it is on, FALSE if it is off). The television is assumed to be off initially.

A method turnOn that turns the television on (sets the “isOn” attribute to true).

A method turnOff that turns the television off (sets the “isOn” attribute to false).

1 class TelevisionSet {

2 int volume = 0;

3 int currentChannel = 1;

4 boolean isOn = false;

5

6 void turnOn(){

7 isOn = true;

8 }

9

10 void turnOff(){

11 isOn = false;

12 }

13 }

In this example, the TelevisionSet class has only two methods – turnOn and turnOff. The “turnOn” method has no return value because it only changes the value of the isOn attribute. Therefore, its return type is void. This method has no parameters because none are needed (it always sets the value of the attribute to true), so the space between the parentheses is empty. The body of the turnOn method contains only one command, which assigns the value true to the isOn attribute. The same applies to the turnOff method.

From the previous example, we can also observe a rule: class attributes can be directly accessed from within any method of the same class. Access is achieved, only by calling the attribute name. In other words, it is not necessary to specify the object name and the attribute name, as when accessing them from outside the class, i.e. from the main method.

Example 2

Add the following methods to the TelevisionSet class and save it as a new class TelevisionSet2:

- A method increaseVolume that increases the value of the volume attribute by one.

- A method decreaseVolume that decreases the value of the volume attribute by one.

- A method muteVolume that completely mutes the volume (sets the volume attribute to 0).

After the modification, the class code looks like this.

1 class TelevisionSet2 {

2

3 int volume = 0;

4 int currentChannel = 1;

5 boolean isOn = false;

6

7 void turnOn(){

8 isOn = true;

9 }

10

11 void turnOff(){

12 isOn = false;

13 }

14

15 void increaseVolume(){

16 volume = volume + 1;

17 }

18

19 void decreaseVolume(){

20 volume = volume - 1;

21 }

22

23 void muteVolume(){

24 volume = 0;

25 }

26 }

The increaseVolume, decreaseVolume, and muteVolume methods have no return value (they do not return anything as a result), so their return type is void. These methods have no parameters.

On the other hand, they increase/decrease current volume settings by adding/subtracting one from the current volume level and storing the new value back in the volume attribute, i.e.:

1 volume = volume + 1;

2

3 volume = volume - 1;

The methods provided in the previous examples do not return any value as a result. However, there are situations where it is necessary to return a value – sometimes it’s needed to return the current value of an attribute or the result of a calculation.

In those cases, the return data type is written instead of void in the method header. If the method returns an integer, the return type is int; if it returns a floating-point number, the return type is double; if it returns a string of characters, the return type is String, etc.

Additionally, within the method body, the return statement must be written to indicate the value that should be returned. Here’s an important note: when the “return” statement is executed, the method execution is terminated. In other words, any command written after the return statement will have no effect (as it will never be executed) - also, it is considered a syntax error.

Example 3

Add the following methods to the TelevisionSet2 class and save it as a new class TelevisionSet3:

- A method changeChannelUp that increases the value of the currentChannel attribute by one.

- A method changeChannelDown that decreases the value of the currentChannel attribute by one.

- A method getCurrentChannel that returns the value of the currentChannel attribute.

- A method getVolume that returns the current value of the volume attribute.

- A method isTurnedOn that returns the current value of the isOn attribute.

- A method printParameters that prints all the attribute values of the television on the screen with appropriate messages.

After all modifications, the class code looks like this.

1 class TelevisionSet3 {

2

3 int volume = 0;

4 int currentChannel = 1;

5 boolean isOn = false;

6

7 void turnOn(){

8 isOn = true;

9 }

10

11 void turnOff(){

12 isOn = false;

13 }

14

15 void increaseVolume(){

16 volume = volume + 1;

17 }

18

19 void decreaseVolume(){

20 volume = volume - 1;

21 }

22

23 void muteVolume(){

24 volume = 0;

25 }

26

27 void changeChannelUp(){

28 currentChannel = currentChannel +1 ;

29 }

30

31 void changeChannelDown(){

32 currentChannel = currentChannel - 1;

33 }

34

35 int getCurrentChannel(){

36 return currentChannel;

37 }

38

39 int getVolume(){

40 return volume;

41 }

42

43 boolean isTurnedOn(){

44 return isOn;

45 }

46

47 void printParameters(){

48 System.out.println("TV is turned on: " + isOn);

49 System.out.println("Volume: " + volume);

50 System.out.println("Current channel: " + currentChannel);

51 }

52 }

The changeChannelUp and changeChannelDown methods do not return any value. However, the methods getCurrentChannel, getVolume, and isTurnedOn do have return values. The getCurrentChannel method is supposed to return the current value of the currentChannel attribute. Practically, this means that it returns the number of the channel currently being shown on the television (e.g., 5). Since it is an integer (the currentChannel attribute is of type int), the return type of the method will also be int. The body of the getCurrentChannel method contains only the return statement to return the value.

For example, if the following line is written in the body of this method, the method would always return the number 2:

1 return 2;

The getVolume method is very similar to the previous one and also returns an int value representing current volume settings. However, the isTurnedOn method returns the value of the isOn attribute, so its return type is boolean.

Finally, the printParameters method only prints the values of all attributes on the screen with appropriate messages. It’s important to note that printing values on the screen is not the same as returning return values. Values printed on the screen cannot be used later (for calculations or other operations), so it is considered that the printParameters method does not actually return any value. Therefore, the return type of this method is void.

It is important to note that the return value of a method has nothing to do with whether the method prints anything to the screen. If a method has a return value, it means that it returns some number, letter, string, etc., which can be saved in a variable and used later in the program for further calculations, processing, and so on. The return type of such a method is not void. When a method only prints a value to the screen, that value is only visually displayed and cannot be retrieved or saved, further processed, etc. (the return type is void).

It is also possible for a method to do both things. For example, of the three methods shown in the following listing, the first only returns the value of the mathematical constant Pi and does not print anything to the screen, the second only prints the value of Pi to the screen and does not return it, and the third does both.

1 double returnPi(){

2 return 3.141592;

3 }

4

5 void printPi(){

6 System.out.println(3.141592);

7 }

8

9 double printAndReturnPi(){

10 System.out.println(3.141592);

11 return 3.141592;

12 }

The question arises, how are methods called? It is similar to calling attributes. In order for methods to be called, an object must first be initialized, and then its method can be called using the object name (variable name) and method name separated by a dot. The difference from calling attributes is that when calling a method, brackets must always be written after the method name (even if the method has no parameters):

1 objectName.methodName();

If a method has a return value, it is recommended to first declare a variable that will receive the method’s return value, and then call the method (though this is not required, the return value can be ignored and discarded). The variable data type must match the return data type of the method:

1 dataType variableName;

2 variableName = objectName.methodName();

Variables

Before moving on to a specific example, it is necessary to clarify what a variable is and what types of variables exist.

A variable represents an identifier (name, letter, expression, etc.) that is linked to some value, and that value can change. Variables are physically represented as a place in the computer’s memory where a value can be stored. The data type of the variable determines the type of the value that can be assigned to it.

For example, a variable of type int can hold an integer value and is physically represented as part of the computer’s memory where an integer value can be stored.

Depending on where they are declared in the code, there are four types of variables:

- Local variables (or just variables) - variables declared within the method’s body.

- Attributes - variables directly belonging to objects of a class. They are defined within the body of the class.

- Global variables - variables that do not belong to individual objects of a class but are used at class level or program level.

- Parameters - variables of a method that are declared in the method’s header (represent the input values for the method). Although they are technically also local (method) variables, we will explicitly differentiate parameters from other local variables for clarity in the rest of the material.

Attributes were explained in detail in the previous lesson, and local variables and parameters will be explained in this lesson. Global variables will be covered in the following lessons.

Example 4

Use the TelevisionSet3 class from the previous example. Create a class TestTelevisionSet that creates an object of the TelevisionSet3 class and calls some of its methods. After each method call, call the printParameters method and notice the changes in the attribute values.

1 class TestTelevisionSet {

2

3 public static void main (String[] args){

4 TelevisionSet3 t = new TelevisionSet3();

5 boolean on;

6 int channel;

7

8 t.printParameters();

9 //It will print:

10 //TV is turned on: false

11 //Volume: 0

12 //Current channel: 1

13

14 t.turnOn();

15 t.printParameters();

16 //It will print:

17 //TV is turned on: true

18 //Volume: 0

19 //Current channel: 1

20

21 t.increaseVolume();

22 t.printParameters();

23 //It will print:

24 //TV is turned on: true

25 //Volume: 1

26 //Current channel: 1

27

28 t.changeChannelUp();

29 t.printParameters();

30 //It will print:

31 //TV is turned on: true

32 //Volume: 1

33 //Current channel: 2

34

35 on = t.isTurnedOn();

36 System.out.println("The television set is turned on: " + on);

37 //It will print:

38 //The television set is turned on: true

39

40 channel = t.getCurrentChannel();

41 System.out.println("The television set is currently displaying "+

42 "channel "+ channel);

43 //It will print:

44 //The television set is currently displaying channel 2

45 }

46 }

When calling a method that has no return value (for example, the printParameters method), the call is similar to calling an object’s attribute. The only difference is that after the method name, you must write parentheses, where the actual values for the parameters are listed. If the method has no parameters, the space between the parentheses remains empty (“()”):

1 t.printParameters();

Calling a method that has a return value is slightly different. This is the case with methods isTurnedOn and getCurrentChannel. The example shows that a local variable on is declared, within the main method’s body. This variable is of type boolean (the same type as the return value of the method isTurnedOn) and receives the return value of the method:

1 on = t.isTurnedOn();

In this way, the method’s return value is not lost (it is saved in the on variable) and can be used in further program execution. This is illustrated by the following line of code from the example. The on variable is used in a print command to display whether the TV is currently on:

1 System.out.println("The television set is turned on: " + on);

Also, this local variable on has limited scope and can only be used within the main method. Finally, if one looks closely, variable t (object pointer) is also a local variable declared in the main method.

The assignment operator (=)

In many of the previous examples and exercises, one operator has frequently been used. This is the assignment operator (=). A few examples related to this operator are given in the following listing:

1 a = 2;

2 m1.cubic = 750;

3 person1.name = "Peter";

4 ind = obj.method1();

5 object1 = object2;

Essentially, this operator allows assigning a value to a variable, attribute, or object.

On the left side, there must always be a variable (local variable, parameter, attribute…) that will receive the value from the right side of the equality sign.

On the right side of the equality sign, there can be:

- a concrete value (-34, true, “E”…),

- a variable (local, parameter, attribute…) of simple or complex data type (object),

- an expression, or

- a method call.

It is important that the data type of the left side matches the data type of the right side (e.g., it’s not possible to assign the value 23.44 to an int variable).

When the assignment operator is used in combination with attributes, variables, and methods that contain or return simple type values, the process is relatively simple. The variable on the left side always gets the value from the right side.

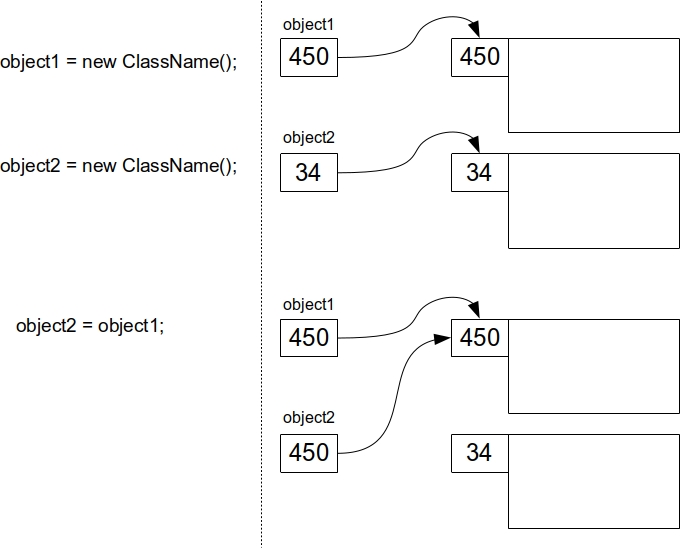

However, things get a bit more complicated if the operands are variables representing objects or pointers (Figure 15). Suppose the first operand is a pointer to an object (variable “object1”), and the second operand is also a pointer to some object (variable “object2”). The assignment operator assigns the contents of the variable on the right side to the variable on the left side. In this case, the memory address stored in the variable “object2” will be assigned to the variable “object1”, so both pointers will point to the same memory location, i.e., the same object. The memory location that no pointer is pointing to will soon be freed by the garbage collection mechanism.

An additional effect that occurs in this case is that now both pointers access the same memory location (the same object). This can be seen in a practical example.

Example 5

Write a class Product that has only one attribute - name, and one method printProduct that prints the value of this attribute to the screen.

1 class Product {

2 String name;

3

4 void printProduct(){

5 System.out.println("Product name is: " + name);

6 }

7 }

Create a TestProduct class that creates two objects of the Product class with product names car and tractor and:

- Print the attribute values of both products.

- Assign the address of the first object to the second object. Print the attribute values again.

- Change the name of the second product to combine harvester and print the values again.

1 class TestProduct {

2

3 public static void main(String[] args) {

4 Product p1 = new Product();

5 Product p2 = new Product();

6

7 p1.name = "car";

8 p2.name = "tractor";

9

10 p1.printProduct();

11 p2.printProduct();

12 //It will print:

13 //Product name is: car

14 //Product name is: tractor

15

16 //Both variables p1 and p2 now point to the

17 // same Product object in memory, the

18 // one named car

19 p2 = p1;

20

21 p1.printProduct();

22 p2.printProduct();

23 // It will print:

24 //Product name is: car

25 //Product name is: car

26

27 //It will change the product name

28 // car to combine harvester

29 p2.name = "combine harvester";

30

31 p1.printProduct();

32 p2.printProduct();

33 // It will print:

34 //Product name is: combine harvester

35 //Product name is: combine harvester

36 }

37 }

At the moment when the variable (pointer) p2 is assigned the content of the pointer p1, both pointers will reference the same memory location, i.e., the same object. From that point on, any changes made to the object pointed to by p2 will also be “visible” to the object pointed to by p1 and vice versa.

Method parameters

Method parameters are values that need to be passed to the method so it can execute properly. A method can have zero, one, or more parameters, and parameters are declared in the method header in a similar way to variables (first the data type, then the parameter name).

This type of parameter is called a formal parameter (or just a parameter). If a method has more than one parameter, they are separated by commas:

1 return_data_type methodName(parameter_data_type parameterName){

2 // Method body

3 }

Calling methods that have parameters is done by placing concrete values or variables between parentheses. When these concrete values or variables are passed as parameters, they are called arguments (real or actual parameters). When calling such a method, the number of parameters, their types, and the order must be respected, otherwise a syntax error will appear.

In other words, if a method takes two parameters of some data type, every call to that method must ensure that exactly two arguments of the corresponding data type and order are passed.

1 methodName(argument);

It’s also important to note that methods of one class can be (if needed) called from another method of the same class relatively simply — by calling the method’s name and passing parameters. It’s not necessary to create an object for this.

Also, the order in which methods are written in the class is not important, so a method can be called even if it’s written “below” the calling method, for example:

1 class X {

2

3 void methodB(){

4 methodA();

5 System.out.println("B");

6 }

7

8 void methodA(){

9 System.out.println("A");

10 }

11 }

Example 6

Create a class CashMachine. This class should have:

- An attribute balance that represents the current amount of money in the machine (a real number). The initial value of this attribute is 5200.0 dollars.

- A method printBalance that prints the current amount of money in the machine (the value of the balance attribute) to the screen.

- A method withdrawAmount that takes as a parameter the amount of money the user wants to withdraw (a real number, e.g., 550.5) and reduces the value of the balance attribute by that amount. Then, it prints the current amount of money to the screen by calling the printBalance method.

- A method depositAmount that takes as a parameter the amount of money the user wants to deposit (a real number) and increases the value of the balance attribute by that amount. Then, it prints the current amount of money to the screen by calling the printBalance method.

- A method getBalance that returns the current amount of money in the machine (the value of the balance attribute).

1 class CashMachine {

2 double balance = 5200.0;

3

4 void printBalance(){

5 System.out.println("The current balance is: "+ balance);

6 }

7

8 //"amount" is a formal parameter

9 void withdrawAmount(double amount){

10 balance = balance - amount;

11

12 //It is possible to call a method from the

13 // same class within another method, if needed

14 printBalance();

15 }

16

17 //"amount" is a formal parameter

18 void depositAmount(double amount){

19 balance = balance + amount;

20

21 //It is possible to call a method from the

22 // same class within another method, if needed

23 printBalance();

24 }

25

26 double getBalance(){

27 return balance;

28 }

29 }

Create a class TestCashMachine in whose main method two objects of the CashMachine class are created. In the first cash machine, you need to deposit 1002.03 dollars and print the balance before and after the deposit. You also need to withdraw 234.55 dollars from the second machine and print the balance before and after the deposit.

1 class TestCashMachine {

2

3 public static void main (String[] args){

4 CashMachine c1 = new CashMachine();

5 CashMachine c2 = new CashMachine();

6

7 //It will print:

8 //The current balance is: 5200.0

9 c1.printBalance();

10

11 //The concrete value 1002.03 is an argument

12 //(a real parameter) which the method

13 // depositAmount receives upon method call.

14 c1.depositAmount(1002.03);

15 //It will print:

16 //The current balance is: 6202.03

17

18 //It will print:

19 //The current balance is: 5200.0

20 c2.printBalance();

21

22 //The concrete value 234.55 is an argument

23 //(a real parameter) which the method

24 // withdrawAmount receives upon method call.

25 c2.withdrawAmount(234.55);

26 //It will print:

27 //The current balance is: 4965.45

28 }

29 }

The methods withdrawAmount and depositAmount each have one parameter. In both cases, the parameter is a real number, so the parameter type is double. These are formal parameters because they are defined within the method header. The parameter name is always arbitrary, but it’s important to use this name within the method body when the parameter is needed. These two methods don’t return a value since they only modify the value of the balance attribute. In addition, both methods call the printBalance method to perform the printing of the balance after each deposit/withdrawal. The call is made simply by invoking the method name and passing the parameters.

In the main method of the TestCashMachine class, you can see the difference between parameters (formal parameters) and arguments (actual parameters). The formal parameter of the method depositAmount is amount, which is of type double, while the argument is the specific number or variable that is passed to the method during the call (in this case, the number 1002.03).

Method parameters can be simple data types (int, double, boolean, char), but also complex types (classes). In other words, a method can have an object as a parameter. Additionally, a method can return an object as a result.

Most common errors

Some of the most common syntax errors related to writing methods are:

- Forgetting to specify void as the return type in the method declaration if the method does not return a value.

- Forgetting to call the return statement in the method body when the method has a return type that is not void.

- Writing the return statement in the method body so that it’s not the last statement in that block of commands.

- Returning a value of the wrong type from the method body via the return statement (e.g., returning a double value when the method is declared to return an int).

- Forgetting to write the opening and/or closing curly braces at the start and end of the method body (command block).

- Forgetting to write parentheses when calling a method, e.g.:

1 m.turnOn;

instead of (correctly):

1 m.turnOn();

- Forgetting to pass arguments when calling a method with parameters, e.g.:

1 m.turnOn();

instead of (correctly):

1 m.turnOn(true);

- Calling a method with the wrong order or type of arguments. For example, a method with the declaration

1 double power(double number, int exponent)

should NOT be called like this:

1 double result = power(2, 9.56);

but instead (correctly):

1 double result = power(9.56, 2);

- Calling a method with a return value and storing that return value in a variable of the wrong type. For example, a method with the declaration

1 double power(double number, int exponent)

should NOT be called like this:

1 int result = power( 9.56, 2 );

but instead (correctly):

1 double result = power( 9.56, 2 );

- On the left side of the assignment operator, there is no variable (but instead a method call, expression, etc.), or the left and right sides are “flipped”, e.g.:

1 m.calculate(12) = x;

2 2 + 3.14 = a;

instead of (correctly):

1 x = m.calculate(12);

2 a = 2 + 3.14;

Other common mistakes that are not syntax errors, but affect the program’s behavior are:

- Incorrectly calling a similarly named method – the name doesn’t match the declaration exactly (case sensitivity, etc.)

- Incorrectly calling a similarly named method with similar parameters – the order or number of parameters doesn’t match the declaration exactly.