Introduction

About this workbook

This workbook covers the basics of object-oriented programming in the Java programming language. The assumption is that the user knows nothing about programming and starts “from scratch.”

It consists of a free companion book (in PDF or EPUB formats) which you are reading right now but, more importantly, a multi-volume collection of tasks which are provided as ZIP files (extras) containing complete courses for the IntelliJ Academy plugin. Solution explanation videos are also available for more complex tasks and are sold separately.

Programming is one of those skills that is best learned through practice. That’s why you often hear and read:

1 "Programming is learned through programming."

No one has learned to program simply by reading books or watching tutorials. Theory is essential, but it’s necessary to “roll up your sleeves” and program what you’re learning. This means: creating your own program, doing a large number of examples, trying different solution variants, analyzing and improving other people’s programs, etc.

This is exactly the motivation behind writing this workbook. There are numerous online courses, textbooks, tutorials, and educational software that contain important lessons about programming. However, there are very few interactive task collections that allow you to solidify that knowledge through concrete programming examples and diverse tasks.

Unfortunately, most of the available task collections are part of online courses, meaning that you cannot practice programming in a real-world software development environment, but through a web-browser and online-based environments with very limited features. That’s why this workbook is provided as an addition of the IDEA IntelliJ enterprise-grade software development environment (actually, its Academy plugin), so one can get used to working in such a setting where all the features and tools available to a professional programmer are present.

You can see the “about” video here.

Introductory video tutorials

Here are some short introductory video tutorials regarding IntelliJ, the Academy plugin, and the Interactive Java workbook just to get you started:

-

IDEA IntelliJ installation video

All of these videos, together with the ones explaining the types of tasks (see the following text) are organized in a playlist for convenience.

Types of tasks in this workbook

Programming is learned just like most other skills: gradually, from easier to harder things. For example, when someone starts learning to play tennis, they first stand still and learn to hit the ball properly. Then they practice and repeat the same move dozens and hundreds of times until they master it. Only then do they move on to the next, more difficult lessons: serving, moving on the court, etc. Only after some time and more lessons do they tackle the most difficult things and move on to playing matches.

The tasks in this workbook are organized according to the same principle. In each chapter, a concept (or multiple concepts) is introduced in a lesson, and then that concept is explored through examples. Then, various and diverse tasks are put upon the user to practice each presented concept (see the Task types overview video):

- Theory lesson (see introductory video) - technically, not a task, but a lesson with examples in code

- Question (see introductory video) - question with multiple answers

- Code completion (see introductory video) - complete the unfinished code

- Syntax correction (see introductory video) - correct all syntax errors in code

- Code correction (see introductory video) - correct the code so it functions as expected

- “Classic” task (see introductory video) - write a solution from scratch

- Alternative solution (see introductory video) - write alternative code that produces the same result

Each subsequent chapter builds on the previous ones. Therefore, you should not “skip” lessons. There are several hundred tasks in total, they are arranged according to difficulty and are divided into three categories:

- EASY (E)

- MEDIUM (M)

- HARD (H)

Specifically, if a task is named Question 8 E, it means that it is a multiple choice question, that it is the eighth in the lesson, and that it is easy (E). Or if a task is named Code Completion 6 M, it is a task of medium difficulty (M) in which you have to complete the unfinished code, and it is the sixth such task in that lesson.

There are several things that keep this workbook interactive so you can get feedback on your task solution and help if you get stuck solving a task (Video: What happens if I cannot solve a task). A predefined solution is provided for each task, and often a hint. The user’s solution is verified by running the provided code tests. A side-by-side comparison of the predefined solution and the user’s solution is also available. What if this still is not enough, and you cannot solve the task? Solution explanation videos are provided for more complex tasks to help you learn and move along.

Solution video explanations are, at this time, sold separately, and are available via Ko-fi memberships (please see here) based on a monthly subscription.

How is this workbook organized

The Interactive Java workbook consists of several parts due to the many topics and even more tasks.

NOTE: Not all parts are completed at this time, but please see the Leanpub page, for updates and purchases.

This is work in progress, so the following list is not yet final. The parts and the topics they cover are as follows:

-

Interactive Java workbook part 1 - demo + full version (COMPLETED)

- Introduction

- Class

- Attribute

- Objects, program execution and output to the screen

-

Interactive Java workbook part 2 (COMPLETED)

- Methods and arithmetic operators

- Constructor

- Global variables and methods

- Constants

- Relationships

- Enumerated type

-

Interactive Java workbook part 3 (COMPLETED)

- Algorithms and control statements (commands)

- The if statement

- The switch statement

- The for statement

- The while statement

- The do-while statement

-

Interactive Java workbook part 4 (COMPLETED)

- Introduction to arrays

- The for-each statement

- Algorithms for working with arrays - overview

- Search and print array elements

- Adding elements to an array

- Replacing array elements

-

Interactive Java workbook part 5 (90% COMPLETED, NOT PUBLISHED YET)

- Deleting array elements

- Group operations on array elements

- Array sorting

- Working with multiple arrays

- Cumulative test 1

- Cumulative test 2

- Cumulative test 3

- Cumulative test 4

- Cumulative test 5

- Cumulative test 6

- Cumulative test 7

- Cumulative test 8

-

Interactive Java workbook part 6 (50% COMPLETED, NOT PUBLISHED YET)

- Arrays of objects

- Working with text (String, StringBuilder)

- Working with dates and times (LocalDate, LocalTime, LocalDateTime)

-

Interactive Java workbook part 7 (10% COMPLETED, NOT PUBLISHED YET)

- Packages and access levels (private, public, protected, default)

- JavaBeans specification

- Inheritance

- The Object class

- Cumulative test 9

- Cumulative test 10

- Cumulative test 11

- Cumulative test 12

- Cumulative test 13

- Cumulative test 14

- Cumulative test 15

- Cumulative test 16

-

Interactive Java workbook part 8 (0% COMPLETED, NOT PUBLISHED YET)

- Abstract classes and inheritance

- Interfaces

- Lists in Java

- Error handling - exceptions

-

Interactive Java workbook part 9 (0% COMPLETED, NOT PUBLISHED YET)

- Input and output streams in Java

- Working with the keyboard

- Working wih textual files

- Serialization of objects

- Cumulative test 17

- Cumulative test 18

- Cumulative test 19

- Cumulative test 20

- Cumulative test 21

- Cumulative test 22

- Cumulative test 23

- Cumulative test 24

What is Programming

Humans use natural language (spoken language) to communicate. Sounds, letters, words, and sentences (with the appropriate grammar) serve to convey a message. Although there are many natural languages, they are based on similar concepts.

However, what happens if we need to convey a message to a computer? Computers do not understand natural language; some form of translation is necessary.

Computers use machine language (binary language). In binary language, everything is represented using only zeros (0) and ones (1). These are the only two “letters.” This language arose due to the way hardware functions (microchips, printed circuit boards, electrical circuits, etc.). At the hardware level, zero means no electricity, and one means there is electricity.

We, humans, use the decimal system to represent numbers. This means ten digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. However, computers only have “digits” 0 and 1. So, how are numbers represented in a computer?

For example, the number 0 is written as 0 in binary, and the number 1 is written as 1. However, the number 2 is represented as 10 in binary because the digit 2 does not exist in binary. The number 10 is the first number larger than 1 that can be written using only the digits 0 and 1. The number 3 is represented as 11, the number 4 as 100, the number 5 as 101, and so on.

1 Decimal Binary

2 0 0

3 1 1

4 2 10

5 3 11

6 4 100

7 5 101

8 6 110

9 7 111

10 8 1000

11 ..............

How are letters represented in binary language? Also as numbers. Each letter is assigned a number that represents it according to the corresponding (character) table. You may have heard of the ASCII table, or UTF-8 and UTF-16?The capital letter “A” is represented as the number 65 (or 1000001 in binary),and the capital letter “B” as 66 (or 1000010), and so on. The Swedish pop band name “ABBA” would be represented as a series of four numbers: 65 66 66 65 (1000001 1000010 1000010 1000001).

1 Characters: A B B A

2 Char codes: 65 66 66 65

3 Binary: 1000001 1000010 1000010 1000001

If we need to give a command to the computer to add two numbers (for example, 65 and 5), it would look something like this in binary:

1 Decimal: 65 + 5 = 70

2 Binary: 1000001 + 101 = 1000110

Let’s say we need to give the computer a more complex command: to load data from a file, search a database, and return the name of a movie, etc. For such a command, we would need to write a lot of zeros and ones. This is extremely complicated if done manually. The potential for errors is enormous.

In the past, commands were indeed written in binary code, but now a different approach is used.

Now, we use (higher) programming languages. These are intermediary languages between humans and computers. A programming language (depending on its complexity) is somewhere between a natural language and machine language. It is similar enough to a natural language so that humans can easily write commands for the computer. Also, it can be easily and quickly (automatically) translated into machine language so that the computer “understands” and executes those commands.

There are many programming languages. Some are “closer” to natural language (“higher” programming languages), while others are closer to binary language (“lower” programming languages). Some are procedural, some are functional, and some are object-oriented (Java is one of them). No programming language is perfect, and each has its advantages, disadvantages and preferred uses.

Every natural language has its grammar. Similarly, every programming language has its syntax. The syntax of a programming language is the set of symbols, reserved words, expressions, and rules that govern the proper use of the language.

In natural languages, violating grammatical rules is undesirable. However, it is often allowed in practice because your conversation partner will likely understand you. In programming languages, any violation of syntax is not allowed and leads to an inability to translate the code into machine language. These violations of syntax are called syntax errors.

Programming is the process in which a person writes commands for a computer in a programming language (always respecting its syntax). Often, the word coding is used instead of programming in casual speech.

As a result of programming, a (computer) program or (computer) application is created.

Source code is the textual record of commands in a programming language, as written by a person. It is usually saved in form of multiple textual files - source code files. Source code is often referred to simply as code.

Executable code is obtained when the commands from the source code are translated into binary language that the computer “understands.” Executable code is called so because it can be executed on the computer without any further translation.

The process (of automatic) translation of source code into binary code is called compiling. Compiling is done by a program called a compiler, and it is only possible if there are no syntax errors in the source code.

The process of running a program, i.e., executing the executable code on a computer, is called program execution or program run.

About the Java programming language

Java is an object-oriented programming language developed by Sun Microsystems, and it is now owned by the Oracle Corporation. This language is free to use and can be downloaded from the Oracle Corporation website.

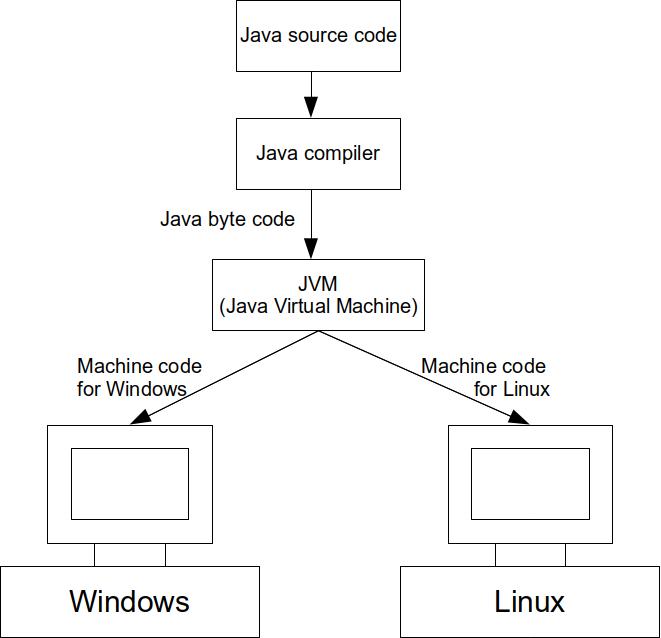

One of the main features of Java is that it is a platform-independent language. This means that, by using Java, programs can be written for Windows Linux, Android, Mac OS X, or any other operating system for which there is a so-called Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

The Java Virtual Machine is specialized software that allows code written in Java to be translated into instructions for the corresponding operating system and hardware during execution (Figure 1). In this way, the same Java program can be used, completely unchanged, on any computer with any operating system (for which there is a JVM, that is). In other words, in order for a Java program to be executed, the JVM for the operating system used must be installed.

The Java installation which only includes the JVM and allows the execution of pre-written Java programs, is called a JRE (Java Runtime Environment).

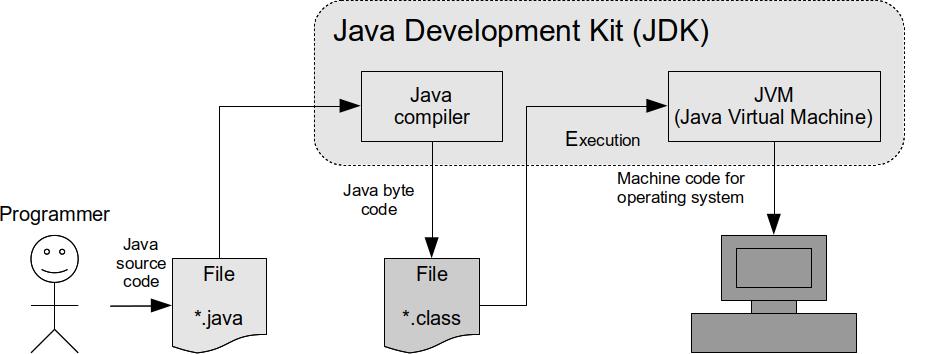

However, if someone wants to create Java programs (and run them), they need to install the JDK (Java Development Kit). The JDK includes the JVM, as well as the Java compiler and the standard Java component library. The Java compiler allows the translation of the source code of a Java program into Java bytecode, which can then be executed on the JVM.

The basic process of creating and running a program in Java can be seen in the following image (Figure 2).

- The programmer first writes the Java code (source code) and saves it in a file with the “.java” extension.

- The next step is to compile this source code, i.e., convert it into Java bytecode. The compiler performs this step upon request and generates files with the “.class” extension.

- Only then can the program be run (execution). When it is executed, the JVM converts the Java bytecode into executable code for the operating system and hardware, and the program begins to execute.

One of the unique features of the Java programming language — platform independence — is achieved precisely because the source code is not directly compiled into executable code but into Java bytecode, which the JVM converts into executable machine code for the specific operating system when the program is run.

The JDK contains only the basic libraries necessary for creating, compiling, and running Java programs. However, the JDK does not include any editor or integrated environment, making it extremely difficult and impractical to write Java programs without these additional tools.

For this reason, there are special classes of programs that use the JDK but add a complete graphical interface and many other tools, all aimed at making it easier and faster to create Java programs. The general term for such a program is Integrated Development Environment (IDE).

Some of the most popular IDEs for Java are:

- IntelliJ IDEA (both commercial and free versions available)

- Eclipse (free)

- Apache NetBeans (free)

Only after installing an IDE along with the JDK can you start writing Java programs. Most IDEs now include a JDK distribution as well so only an IDE installation is needed.

However, there is also an alternative. Recently, online code editors and online IDEs have become very popular, and they do not require any installation. Instead, you can work with them online through a web browser.

Some popular free online environments and editors are:

- Replit IDE (not free, but there is a free version)

The advantages of these online environments are that installation is not required and you work directly through the browser, which makes programming possible even on other devices that have a browser (smartphones, tablets, etc.). Therefore, they can be a good choice for someone just starting to learn programming, and they typically support multiple programming languages at once.

On the other hand, these online environments can cumbersome to work with - an accidental page refresh can erase your code. They are very simple and have very limited features, so they are not a good choice for creating more complex programs or applications. Some online environments only support working with a single file. Additionally, these online environments tend to be slower than standard IDEs and do not allow the use of additional Java libraries or the creation of Java applications with graphical interfaces, further limiting their usability.