2. The View From 30,000ft

This chapter is a high-level overview of the processes involved in executing a Python program. Regardless of the complexity of a Python program, the techniques described here are the same. In subsequent chapters, we zoom in to give details on the various pieces of the puzzle. The excellent explanation of this process provided by Yaniv Aknin in his Python Internal series provides some of the basis and motivation for this discussion.

A method of executing a Python script is to pass it as an argument to the Python interpreter as such $python test.py. There are other ways of interacting with the interpreter

- we could start the interactive interpreter, execute a string as code, etc. However, these methods are not of interest to us.

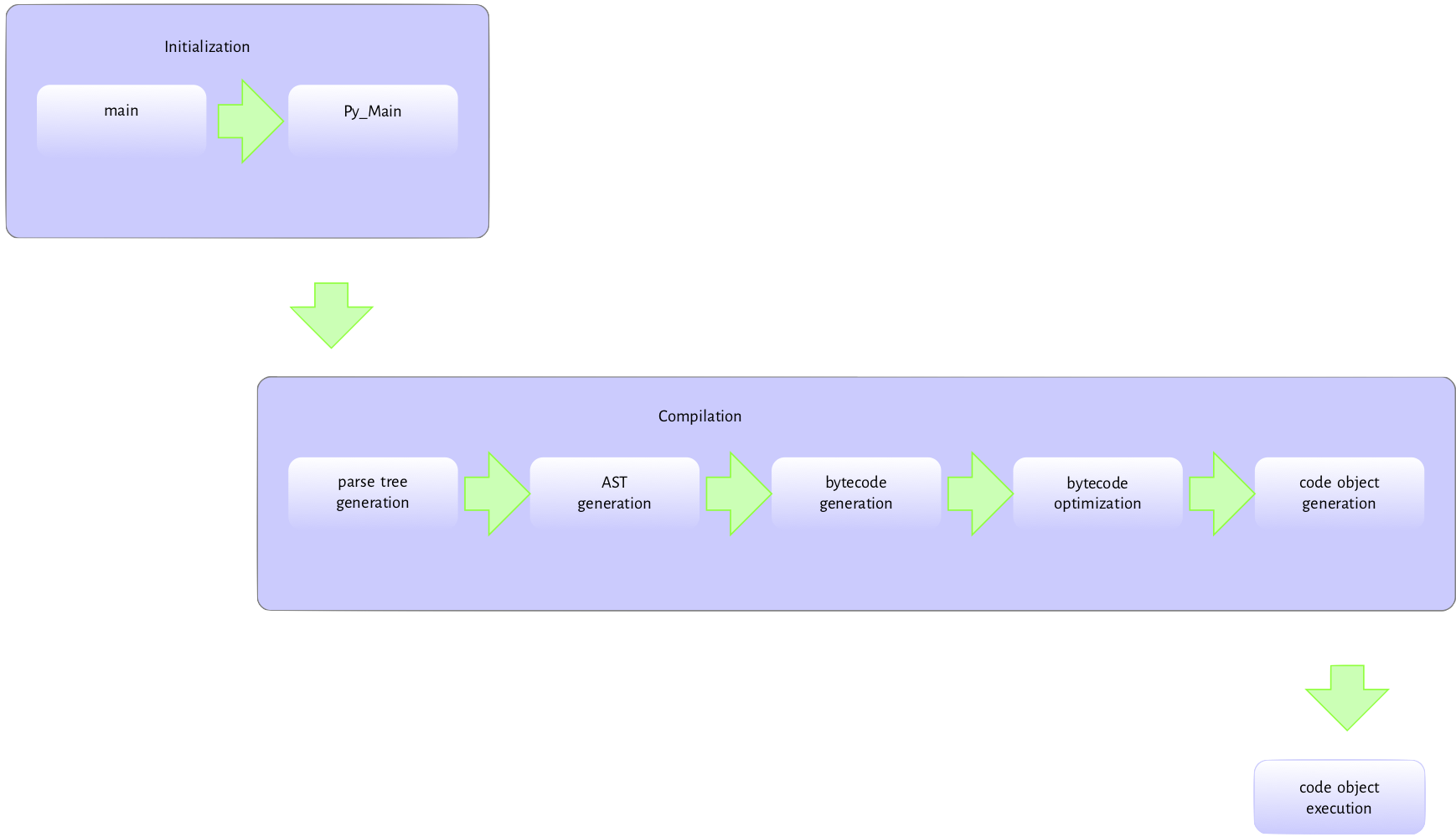

Figure 2.1 is

the flow of activities involved in executing a module passed to the interpreter at the command-line.

The Python executable

is a C program like any other C program such as the Linux kernel or a simple hello world

program in C so pretty much the same process happens when we run the Python interpreter executable.

The executable’s entry point is the main method in the Programs/python.c. This main method handles basic initialization, such as memory allocation, locale setting, etc. Then, it invokes the Py_Main function in Modules/main.c responsible for the python specific initializations. These include parsing command-line arguments and setting program

flags, reading environment variables, running hooks, carrying out hash randomization, etc. After, Py_Main calls the Py_Initialize function in Programs/pylifecycle.c; Py_Initialize is responsible for initializing the interpreter and all associated objects and data structures required by the Python runtime. After Py_Initialize completes successfully, we now have access to all Python objects.

The interpreter state and interpreter state data structures are two examples of data structures that are initialized by the Py_Initialize call.

A look at the data structure definitions for these provides some context into their functions. The interpreter and thread states are C structures with pointers to fields that hold information needed for executing a program. Listing 2.1 is the interpreter state typedef (just assume that

typedef is C jargon for a type definition though this is not entirely true).

1 typedef struct _is {

2

3 struct _is *next;

4 struct _ts *tstate_head;

5

6 PyObject *modules;

7 PyObject *modules_by_index;

8 PyObject *sysdict;

9 PyObject *builtins;

10 PyObject *importlib;

11

12 PyObject *codec_search_path;

13 PyObject *codec_search_cache;

14 PyObject *codec_error_registry;

15 int codecs_initialized;

16 int fscodec_initialized;

17

18 PyObject *builtins_copy;

19 } PyInterpreterState;

Anyone who has used the Python programming language long enough may recognize a few of the fields mentioned in this structure (sysdict, builtins, codec)*.

- The

*nextfield is a reference to another interpreter instance as multiple python interpreters can exist within the same process. - The

*tstate_headfield points to the main thread of execution - if the Python program is multithreaded, then the interpreter is shared by all threads created by the program - we discuss the structure of a thread state shortly. - The

modules,modules_by_index,sysdict,builtins, andimportlibare self-explanatory - they are all defined as instances ofPyObjectwhich is the root type of all Python objects in the virtual machine world. We provide more details about Python objects in the chapters that will follow. - The

codec*related fields hold information that helps with the location and loading of encodings. These are very important for decoding bytes.

A Python program must execute in a thread. The thread state structure contains all the information needed by a thread to run some code. Listing 2.2 is a fragment of the thread data structure.

1 typedef struct _ts {

2 struct _ts *prev;

3 struct _ts *next;

4 PyInterpreterState *interp;

5

6 struct _frame *frame;

7 int recursion_depth;

8 char overflowed;

9

10 char recursion_critical;

11 int tracing;

12 int use_tracing;

13

14 Py_tracefunc c_profilefunc;

15 Py_tracefunc c_tracefunc;

16 PyObject *c_profileobj;

17 PyObject *c_traceobj;

18

19 PyObject *curexc_type;

20 PyObject *curexc_value;

21 PyObject *curexc_traceback;

22

23 PyObject *exc_type;

24 PyObject *exc_value;

25 PyObject *exc_traceback;

26

27 PyObject *dict; /* Stores per-thread state */

28 int gilstate_counter;

29

30 ...

31 } PyThreadState;

More details on the interpreter and the thread state data structures will follow in subsequent chapters. The initialization process also sets up the import mechanisms as well as rudimentary stdio.

After the initialization, the Py_Main function invokes the run_file function also in the main.c module. The following series of function calls:

PyRun_AnyFileExFlags -> PyRun_SimpleFileExFlags->PyRun_FileExFlags->PyParser_ASTFromFileObject

are made to the PyParser_ASTFromFileObject function.

The PyRun_SimpleFileExFlags function call creates the __main__ namespace in which the

file contents will be executed. It also checks for the presence of a pyc version of the module -

the pyc file contains the compiled version of the executing module. If a pyc version exists, it will attempt to read and execute it. Otherwise, the interpreter invokes thePyRun_FileExFlags function followed by a call to

the PyParser_ASTFromFileObject function and then the

PyParser_ParseFileObject function. The PyParser_ParseFileObject function reads the module content and builds a parse tree from it. The PyParser_ASTFromNodeObject function is then called with the parse tree as an argument and creates an abstract syntax tree (AST) from the parse tree.

The AST generated is then passed to the run_mod function. This function invokes the PyAST_CompileObject function that creates code objects from the AST. Do note that the bytecode generated during the call to PyAST_CompileObject

is passed through a simple peephole optimizer that carries out low hanging optimization of the generated bytecode

before creating the code object.

With the code objects created, it is time to execute the instructions encapsulated by the code objects.

The run_mod function invokes PyEval_EvalCode from the ceval.c file with

the code object as an argument. This results in another series of function calls:

PyEval_EvalCode->PyEval_EvalCode->_PyEval_EvalCodeWithName->_PyEval_EvalFrameEx. The code object is an argument to most of these functions.

The _PyEval_EvalFrameEx is the actual execution loop that handles executing the code objects. This function gets called with a frame object as an argument. This frame object provides the context for executing the code object. The execution loop reads and executes instructions from an array of instructions, adding or removing objects from the value stack in the process (where is this value stack?), till there are no more instructions to execute or something exceptional that breaks this loop occurs.

Python provides a set of functions that one can use to explore actual code objects. For example, a a simple program can be compiled into a code object and disassembled to get the opcodes that are executed by the Python virtual machine, as shown in listing 2.3.

1 >>> from dis import dis

2 >>> def square(x):

3 ... return x*x

4 ...

5

6 >>> dis(square)

7 2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

8 2 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

9 4 BINARY_MULTIPLY

10 6 RETURN_VALUE

The ./Include/opcodes.h file contains a listing of the Python Virtual Machine’s bytecode instructions. The opcodes are pretty straight forward conceptually. Take our example from listing 2.3 with four

instructions - the LOAD_FAST opcode loads the value of its argument (x in this case) onto an evaluation (value) stack. The Python virtual machine is a

stack-based virtual machine, so values for operations and results from operations live on a stack.

The BINARY_MULTIPLY opcode then pops two items from the value stack, performs binary multiplication on both values, and places the result back on the value stack. The RETURN VALUE opcode pops a

value from the stack, sets the return value object to this value, and breaks out of the interpreter loop.

From the disassembly in listing 2.3, it is pretty clear that this rather simplistic explanation of the operation of the interpreter loop leaves out a lot of details. A few of these outstanding questions may include.

After the module’s execution, the Py_Main function continues with the clean-up process. Just as

Py_Initialize performs initialization during the interpreter startup, Py_FinalizeEx

is invoked to do some clean-up work; this clean-up process involves waiting for threads to exit, calling

any exit hooks, freeing up any memory allocated by the interpreter that is still in use, and so on, paving the way for the interpreter to exit.

The above is a high-level overview of the processes involved in executing a Python module. A lot of details are left out at this stage, but all will be revealed in subsequent chapters. We continue in the next chapter with a description of the compilation process.