11. From Class code to bytecode

We have covered a lot of ground discussing the nuts and bolts of how the Python virtual machine or interpreter (whichever you want to call it) executes your code but for an object-oriented language like Python, we have left out one of the essential parts - the nuts and bolts of how a user-defined class gets compiled down to bytecode and executed.

Our discussions on Python objects have provided us with a rough idea of how new classes may be created; however, this intuition may not fully capture the whole process from the moment a user defines a class in source to the bytecode resulting from compiling that class. This chapter aims to bridge that gap and provide an exposition on this process.

As usual, we start with the straightforward user-defined class listing 11.0.

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

Listing 11.1 is the disassembly of the class from Listing 11.0.

0 LOAD_BUILD_CLASS

2 LOAD_CONST 0 (<code object Person at 0x102298b70, file "str\

ing", line 2>)

4 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Person')

6 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

8 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Person')

10 CALL_FUNCTION 2

12 STORE_NAME 0 (Person)

14 LOAD_CONST 2 (None)

16 RETURN_VALUE

We are interested in bytes 0 to 12, the actual opcodes that create the new class object and store it for future reference by its name (Person in our example). Before, we expand on the opcodes above; we look at the process of class creation as specified by the Python documentation. The description of the process in the documentation, though done at a very high level, is pretty straightforward. We infer from Python documentation that the class creation process involves the following steps.

- The body of the class statement is isolated into a code object.

- The appropriate metaclass for class instantiation is determined.

- A class dictionary representing the namespace for the class is prepared.

- The code object representing the class’ body is executed within this namespace.

- The class object is created.

During the final step, the class object is created by instantiating the type class, passing in the class name, base classes and class dictionary as arguments. Any __prepare__ hooks are run before instantiating the class object. The metaclass used in the class object creation can be explicitly specified by supplying the metaclass keyword argument in the class definition. If a metaclass is not provided, the interpreter examines the first entry in the tuple of any base classes. If base classes are not used, the interpreter searches for the global variable

__metaclass__ and if not found, Python uses the default meta-class.

The whole class creation process starts with a load of the __build_class function onto the value stack. This function is responsible for all the type creation heavy lifting.

Next, type’s body code object, already compiled into a code object, is loaded on the stack by the instruction at offset 2 - LOAD_CONST.

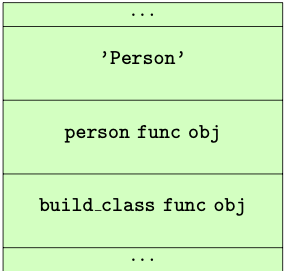

This code object is then wrapped into a function object by the MAKE_FUNCTION opcode and placed back on the stack; it will soon become clear why this happens. By offset 10; the evaluation stack looks similar to that in Figure 11.0.

CALL_FUNCTIONAt offset 10, CALL_FUNCTION handles invokes the __build_class__ function with the two values above it on the evaluation stack as argument (the argument to CALL_FUNCTION is two). The __build_class__ function in the Python/bltinmodule.c module is the workhorse that creates our class.

A significant part of the function is devoted to sanity checks - check for the right arguments, checks for correct type etc. After these sanity checks, the function then has to decide on the right metaclass. The rules for determining the correct metaclass are reproduced verbatim from the Python documentation.

- if no bases and no explicit metaclass are given, then

type()is used- if an explicit metaclass is given and it is not an instance of

type(), then it is used directly as the metaclass- if an instance of type() is given as the explicit metaclass, or bases are defined, then the most derived metaclass is used

The most derived metaclass is selected from the explicitly specified metaclass (if any) and the metaclasses (i.e.

type(cls)) of all specified base classes. The most derived metaclass is one which is a subtype of all of these candidate metaclasses. If none of the candidate metaclasses meets that criterion, then the class definition will fail withTypeError.

The actual snippet from the __build_class function that handles the metaclass

resolution is in listing 11.2, and it has been annotated a bit more to provide some more

clarity.

...

/* kwds are values passed into brackets that follow class name

e.g class(metalcass=blah)*/

if (kwds == NULL) {

meta = NULL;

mkw = NULL;

}

else {

mkw = PyDict_Copy(kwds); /* Don't modify kwds passed in! */

if (mkw == NULL) {

Py_DECREF(bases);

return NULL;

}

/* for all intent and purposes &PyId_metaclass references the string "me\

taclass"

but the &PyId_* macro handles static allocation of such strings */

meta = _PyDict_GetItemId(mkw, &PyId_metaclass);

if (meta != NULL) {

Py_INCREF(meta);

if (_PyDict_DelItemId(mkw, &PyId_metaclass) < 0) {

Py_DECREF(meta);

Py_DECREF(mkw);

Py_DECREF(bases);

return NULL;

}

/* metaclass is explicitly given, check if it's indeed a class */

isclass = PyType_Check(meta);

}

}

if (meta == NULL) {

/* if there are no bases, use type: */

if (PyTuple_GET_SIZE(bases) == 0) {

meta = (PyObject *) (&PyType_Type);

}

/* else get the type of the first base */

else {

PyObject *base0 = PyTuple_GET_ITEM(bases, 0);

meta = (PyObject *) (base0->ob_type);

}

Py_INCREF(meta);

isclass = 1; /* meta is really a class */

}

...

With the metaclass found, __build_class then proceeds to check if any __prepare__ attribute exists

on the metaclass; if any such attribute exists the class namespace is prepared by executing the

__prepare__ hook passing the class name, class bases and any additional keyword arguments from the

class definition. This hook is used to customize class behaviour. The following example in listing 11.3 which

is taken from the example on metaclass definition and use of the python documentation

shows an example of how the __prepare__ hook can be used to implement a class with attribute ordering.

class OrderedClass(type):

@classmethod

def __prepare__(metacls, name, bases, **kwds):

return collections.OrderedDict()

def __new__(cls, name, bases, namespace, **kwds):

result = type.__new__(cls, name, bases, dict(namespace))

result.members = tuple(namespace)

return result

class A(metaclass=OrderedClass):

def one(self): pass

def two(self): pass

def three(self): pass

def four(self): pass

>>> A.members

('__module__', 'one', 'two', 'three', 'four')

The __build_class function returns an empty new dict if there is no __prepare__ attribute defined

on the metaclass but if there is one, the namespace that is used is the result of

executing the __prepare__ attribute like the snippet in listing 11.4.

...

// get the __prepare__ attribute

prep = _PyObject_GetAttrId(meta, &PyId___prepare__);

if (prep == NULL) {

if (PyErr_ExceptionMatches(PyExc_AttributeError)) {

PyErr_Clear();

ns = PyDict_New(); // namespace is a new dict if __prepare__ is not \

defined

}

else {

Py_DECREF(meta);

Py_XDECREF(mkw);

Py_DECREF(bases);

return NULL;

}

}

else {

/** where __prepare__ is defined, the namespace is the result of executi\

ng

the __prepare__ attribute **/

PyObject *pargs[2] = {name, bases};

ns = _PyObject_FastCallDict(prep, pargs, 2, mkw);

Py_DECREF(prep);

}

if (ns == NULL) {

Py_DECREF(meta);

Py_XDECREF(mkw);

Py_DECREF(bases);

return NULL;

}

...

After handling the __prepare__ hook, it is now time for the actual class object to be created.

First, the execution of the class body’s code object happens within the namespace from the previous paragraph. To understand why take a look at this code object’s bytecode in listing 11.5.

1 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (__name__)

2 STORE_NAME 1 (__module__)

4 LOAD_CONST 0 ('test')

6 STORE_NAME 2 (__qualname__)

2 8 LOAD_CONST 1 (<code object __init__ at 0x102a80660, fi\

le "string", line 2>)

10 LOAD_CONST 2 ('test.__init__')

12 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

14 STORE_NAME 3 (__init__)

16 LOAD_CONST 3 (None)

18 RETURN_VALUE

After executing this code object, the namespace will contain all the attributes of the class, i.e. class attributes, methods etc. This namespace subsequently used as an argument for a function call to the metaclass as shown in listing 11.6.

// evaluate code object for body within namespace

none = PyEval_EvalCodeEx(PyFunction_GET_CODE(func), PyFunction_GET_GLOBALS(func\

), ns,

NULL, 0, NULL, 0, NULL, 0, NULL,

PyFunction_GET_CLOSURE(func));

if (none != NULL) {

PyObject *margs[3] = {name, bases, ns};

/**

* this will 'call' the metaclass creating a new class object

**/

cls = _PyObject_FastCallDict(meta, margs, 3, mkw);

Py_DECREF(none);

}

Assuming we are using the type metaclass, calling the type means dereferencing the attribute in the

tp_call slot of the class. The tp_call function then, in turn, dereferences the attribute in the

tp_new slot which creates and returns our brand new class object.

The cls value returned is then placed back on the stack and stored to the Person variable.

There we have it, the process of creating a new class and this is all there is to it in Python.