10. The Block Stack

One of the data structures that does not get as much coverage as it should is the block stack, the other stack within a frame object. Most discussions of the Python VM mention the block stack passingly

but then focus on the evaluation stack. However, the block stack is critical for exception handling. There are probably other

methods of implementing exception handling but as will become evident as we progress through this chapter, using a stack, the block stack, makes it incredibly simple to implement exception handling. The block stack and exception handling are so intertwined that one will not fully understand the need for the block stack without actually

considering exception handling. Loops also make use of the block stack, but it is difficult

to see a reason for block stacks with loops until one looks at how loop constructs like break interact

with exception handlers. The block stack makes the implementation of such interactions a straightforward affair.

The block stack is a stack data structure field within a frame object. Just like the evaluation stack, values are pushed to and popped from the block stack during the execution of a frame’s

code. However, the block stack is used only for handling loops and exceptions. The best way to explain the block stack is with an example, so we illustrate with a simple try...finally construct within a loop

as shown in the snippet in listing 10.0.

def test():

for i in range(4):

try:

break

finally:

print("Exiting loop")

Listing 10.1 is the disassembly of code from Listing 10.0.

2 0 SETUP_LOOP 34 (to 36)

2 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (range)

4 LOAD_CONST 1 (4)

6 CALL_FUNCTION 1

8 GET_ITER

>> 10 FOR_ITER 22 (to 34)

12 STORE_FAST 0 (i)

3 14 SETUP_FINALLY 6 (to 22)

4 16 BREAK_LOOP

18 POP_BLOCK

20 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

6 >> 22 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (print)

24 LOAD_CONST 2 ('Exiting loop')

26 CALL_FUNCTION 1

28 POP_TOP

30 END_FINALLY

32 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 10

>> 34 POP_BLOCK

>> 36 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

38 RETURN_VALUE

The combination of a for loop and try ... finally leads to a lot of instructions even for such a simple function as listing 10.1 shows.

The opcodes of interest here are the SETUP_LOOP and

SETUP_FINALLY opcodes so we look at the implementations of these to get the gist of what it does (all SETUP_* opcodes map to the same implementation).

The implementation for the SETUP_LOOP opcode is a simple function call - PyFrame_BlockSetup(f, opcode, INSTR_OFFSET() + oparg, STACK_LEVEL());.

The arguments are pretty self-explanatory - f is the frame, opcode is the currently executing opcode, INSTR_OFFSET() + oparg is the instruction delta for the next instruction after that block (for the above code the delta is 50 for the SETUP_LOOP), and the STACK_LEVEL denotes how many items are on the value stack of the frame. The function call creates a new block and pushes it on the block stack. The information contained in this block is enough for the virtual machine to continue execution should something happen while in that block.

Listing 10.2 is the implementation of this function.

void PyFrame_BlockSetup(PyFrameObject *f, int type, int handler, int level){

PyTryBlock *b;

if (f->f_iblock >= CO_MAXBLOCKS)

Py_FatalError("XXX block stack overflow");

b = &f->f_blockstack[f->f_iblock++];

b->b_type = type;

b->b_level = level;

b->b_handler = handler;

}

The handler in Listing 10.2 is the pointer to the next instruction that should be executed after the SETUP_* block.

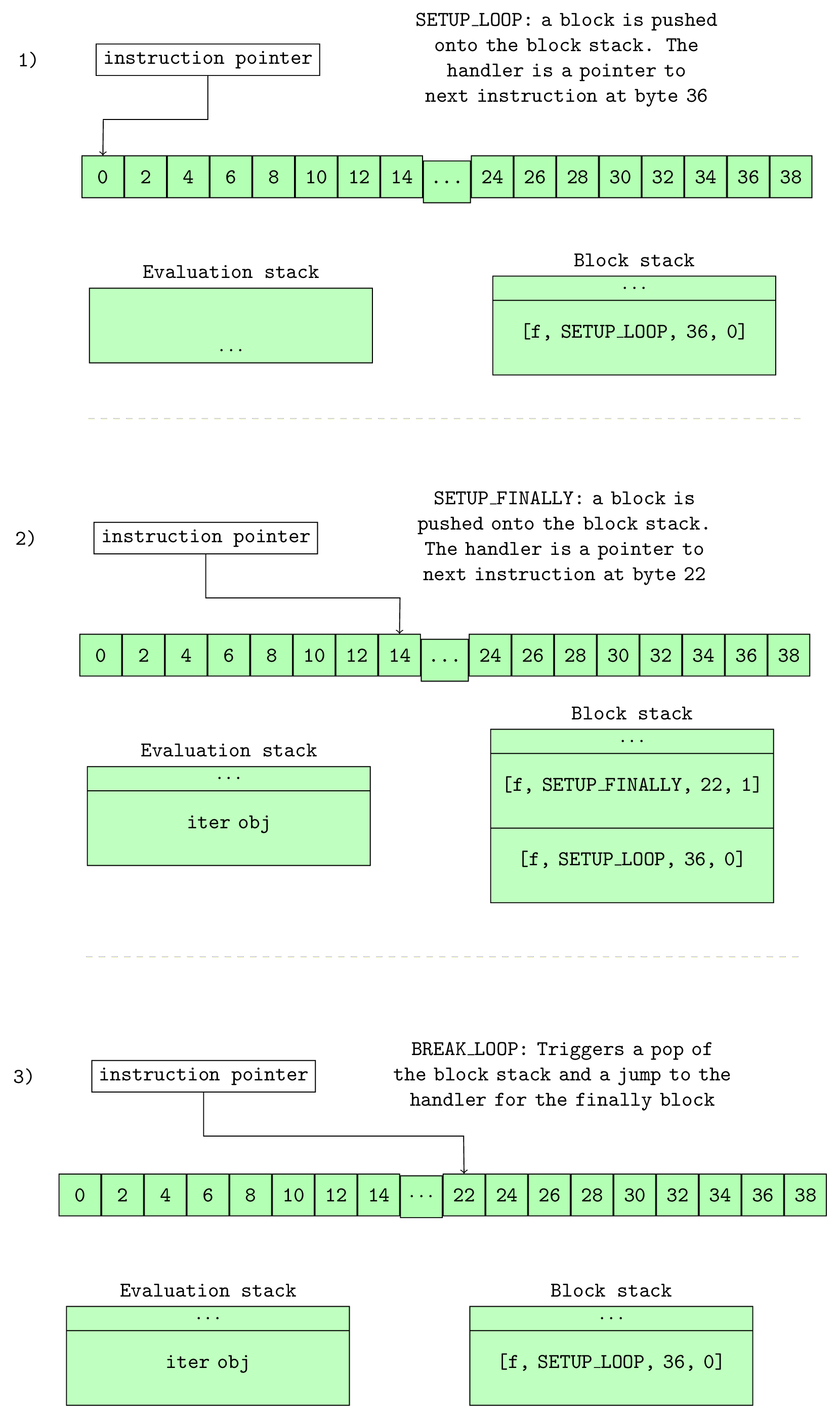

A visual representation of the example from above is illustrative - figure 10.0 shows this using a subset of the bytecode.

Figure 10.0 shows how the block stack varies during the execution of instructions.

The first diagram of figure 10.0 shows a single SETUP_LOOP block placed on the block stack after the execution of the SETUP_LOOP opcode. The instruction at offset 36 is the handler for this block, so when this stack is popped during normal execution, the interpreter will jump to that offset and continue execution. Another block is pushed onto the block stack during the execution of the SETUP_FINALLY opcode. We can see that as the stack is

Last In First Out data structure, the finally block will be the first out - recall that finally must be executed regardless of the break statement.

A simple illustration of the use of a block stack is when the break statement is encountered while inside the exception handler within the loop. The why variable is set to WHY_BREAK during the execution of the BREAK_LOOP and a jump to the fast_block_end code label, where the block stack unwinding is handled, is performed.

The second diagram of figure 10.0 shows this. Unwinding is just a fancy name for popping blocks on the stack and executing their handler. So in this case, the SETUP_FINALLY

block is popped off the stack, and the interpreter jumps to its handler at bytecode offset 22. Execution continues from that offset till the END_FINALLY statement. Since the why

code is a WHY_BREAK; a jump is executed to the fast_block_end code label once again where

more stack unwinding happens - the loop block is left on the stack. This time around (not shown in figure 10.0), the block popped from the stack has a handler at byte offset 36, so the execution continues at that bytecode offset, thus exiting the loop.

The use of the block stack dramatically simplifies the implementation of the virtual machine implementation.

If loops are not implemented with a block stack, an opcode such as the BREAK_LOOP would need a jump destination. If we then throw in a try..finally construct with that break statement we get a complex implementation where we would have to keep track of optional jump destinations within finally blocks

and so on.

10.1 A Short Note on Exception Handling

With this basic understanding of the block stack, it is not difficult to fathom the implementation of exceptions and exception handling. Take the snippet in Listing 10.3 that tries to add a number to a string.

def test1():

try:

2 + 's'

except Exception:

print("Caught exception")

Listing 10.4 shows the opcodes generated from this simple function.

We should have a conceptual idea of how this code block will execute if an exception should occur given the previous explanation. In summary, we expect the PyNumber_Add function from the Objects/abstract.c

module to return a NULL for the BINARY_ADD opcode. In addition to returning a NULL value, the function also sets exception values on the currently executing thread’s thread state. Recall, that the thread state has the

curexc_type, curexc_value and curexc_traceback fields for holding the current exception in the thread of execution; these fields prove very useful while unwinding the block stack in search of exception handlers. You can follow the chain of function calls from the binop_type_error function in the

Objects/abstract.c module all the way to the PyErr_SetObject and PyErr_Restore functions in the Python/errors.c module where the exception gets set on the thread state.

With the exception values set on the currently executing thread’s thread state and a NULL value returned from the function call, the interpreter loop executes a jump to the error label where all the magic of exception

handling occurs or not. For our trivial example above, we have only one block on the block stack, the SETUP_EXCEPT block with a handler at bytecode offset 14.

The stack unwinding begins after the jump to error handler label. The exception values - traceback, exception value and exception type, are pushed

on top of the value stack, the SETUP_EXCEPT handler gets popped from the block stack, and then there is a jump to the handler - byte offset 14 in this case where the execution continues. Observe the

bytecodes from offset 16 to offset 20 in listing 10.4; here the Exception class is loaded onto the stack, and then compared with the raised exception value present on the stack. If the exceptions match then normal execution can continue with the popping of exception and tracebacks from value stack and execution

of any of the error handler code. When there is no exception match, the END_FINALLY instruction is executed, and since there is still an exception on the stack, there is a break from the exception loop.

In the case where there is no exception handling mechanism, the opcodes for the test function are

more straightforward as shown in listing 10.5.

The opcodes do not place any value on the block stack so when an exception followed by a jump to the error handling label occurs, there is no block to be unwound from the stack causing the loop to be exit and the error to be dumped to the user.

Although some implementation details are left out, this chapter covers the fundamentals of the interaction between the block stack and error handling in the Python virtual machine. There are other details such as handling exceptions within exceptions, nested exception handlers and so on. However, we conclude this short intermezzo at this point.