7. Interpreter and Thread States

As mentioned in previous chapters, initializing the interpreter and thread state data structures is one of the steps involved in the bootstrap of the Python interpreter. In this chapter, we provide a detailed look at these data structures.

7.1 The Interpreter state

The Py_Initialize function in the pylifecycle.c module is one of the bootstrap functions invoked

during the initialization of the Python interpreter. This function handles the set-up of the Python runtime as well as the initialization of the interpreter state and thread state data structures among

other things.

The interpreter state is a straightforward data structure that captures the global state shared by a set of cooperating threads of execution in a Python process. Listing 7.0 is a cross-section of this data structure’s definition.

typedef struct _is {

struct _is *next;

struct _ts *tstate_head;

PyObject *modules;

PyObject *modules_by_index;

PyObject *sysdict;

PyObject *builtins;

PyObject *importlib;

PyObject *codec_search_path;

PyObject *codec_search_cache;

PyObject *codec_error_registry;

int codecs_initialized;

int fscodec_initialized;

...

PyObject *builtins_copy;

PyObject *import_func;

} PyInterpreterState

The fields in listing 7.0 should be familiar if one covered the prior materials in this book, and has used Python for a considerable amount of time. We discuss some of the fields of the interpreter state data structure once again.

-

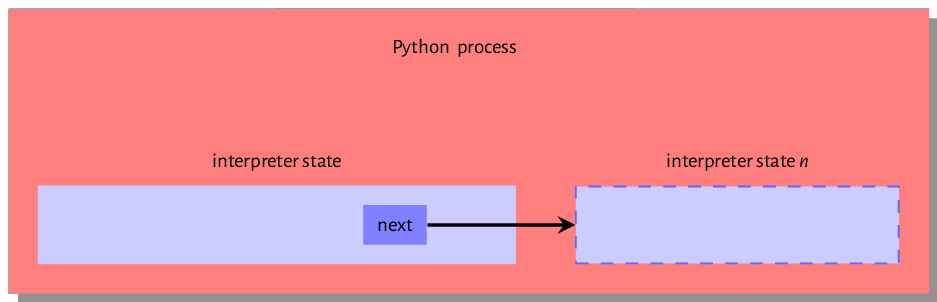

*next: There can be multiple interpreter states within a single OS process that is running a python executable. This*nextfield references another interpreter state data structure within the python process if such exist, and these form a linked list of interpreter states, as shown in figure 7.0. Each interpreter state has its own set of variables that will be used by a thread of execution that references that interpreter state. However, all interpreter threads in the process share the same memory space and Global Interpreter Lock.

Figure 7.0: Interpreter state within the executing python process -

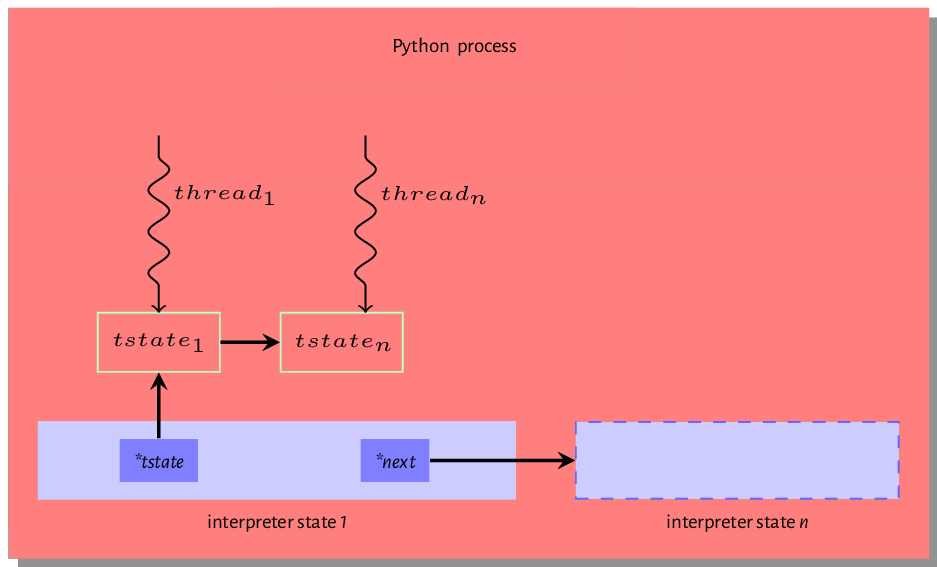

*tstate_head: This field references the thread state of the currently executing thread or in the case of a multithreaded program, the thread that currently holds the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). This is a data structure that maps to an executing operating system thread.

The remaining fields are variables that are shared by all cooperating threads of the interpreter state. The modules field is a table of installed Python modules - we see how the interpreter finds these modules later on when we discuss the import system,

the builtins field is a reference to the built-in sys module. The content of this module is the set of built-in functions such as len, enumerate etc. and the Python/bltinmodule.c module

contains implementations for most of the contents of the module. The importlib is a field that references the implementation of the import mechanism - we speak a bit more about this when we discuss the import system in detail.

The *codec_search_path, *codec_search_cache, *codec_error_registry, *codecs_initialized and

*fscodec_initialized are fields that all relate to codecs that Python uses to encode and decode bytes and text. The interpreter uses values in these fields to locate such codecs as well as handle errors related to using such codecs.

An executing Python program is composed of one or more threads of execution. The interpreter has to maintain some state for each thread of execution, and this works by maintaining a thread state data structure for each thread of execution. We look at this data structure next.

7.2 The Thread state

Reviewing the Thread state data structure in listing 7.1, one can see that the thread state data structure is a more involved data structure than the interpreter state data structure.

typedef struct _ts {

struct _ts *prev;

struct _ts *next;

PyInterpreterState *interp;

struct _frame *frame;

int recursion_depth;

char overflowed;

char recursion_critical;

int tracing;

int use_tracing;

Py_tracefunc c_profilefunc;

Py_tracefunc c_tracefunc;

PyObject *c_profileobj;

PyObject *c_traceobj;

PyObject *curexc_type;

PyObject *curexc_value;

PyObject *curexc_traceback;

PyObject *exc_type;

PyObject *exc_value;

PyObject *exc_traceback;

...

} PyThreadState;

A thread state data structure’s previous and next fields reference thread states created before and just after the given thread state. These fields form a doubly-linked list of thread states

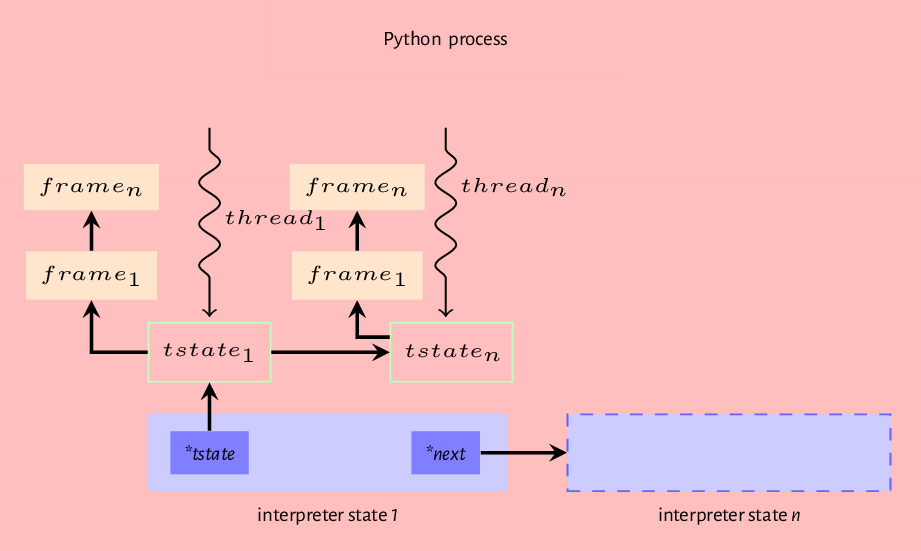

that share a single interpreter state. The interp field references the thread state’s interpreter state. The frame references the current frame of execution; the value referenced by this field changes when the code object that is executing changes.

The recursion_depth, as the name suggests, specifies how deep the stack frame should get during a

recursive call. The overflowed flag is set when the stack overflows. After a

stack overflow, the thread allows 50 more calls for clean-up operations. The

recursion_critical flag signals to the thread that the code being executed should not overflow. The tracing and use_tracing flag are related to functionality for tracing the execution of the thread. The *curexc_type, *currexc_value, *curexc_traceback, *exc_type, *exc_value

and *curexc_traceback are fields that are all used in the exception handling process as will be seen

in subsequent chapters.

It is essential to understand the difference between the thread state and an actual thread. The thread state is just a data structure that encapsulates some state for an executing thread. Each thread state is associated with a native OS thread within the Python process. Figure 7.1 is an excellent visual illustration of this relationship. We can see that a single python process is home to at least one interpreter state and each interpreter state is home to one or more thread states, and each of these thread states maps to an operating system thread of execution.

Operating System threads and associated Python thread states are created either during the initialization of the interpreters or when invoked by the threading module. Even with multiple threads alive within a Python process, only one thread can actively carry out CPU bound tasks at any given time. This is because an executing thread must hold the GIL to execute byte code within the python virtual machine. This chapter will not be complete without a look at the famous or infamous GIL concept so we take this on in the next section

Global Interpreter Lock - GIL

Although python threads are operating system threads, a thread cannot execute python bytecode unless such thread holds the GIL. The operating system may

schedule a thread that does not hold the

GIL to run but as we will see, all such a thread can do is wait to get the GIL

and only when it holds the GIL is it able to execute bytecode. We take a look at this whole process.

When the interpreter startups, a single main thread of execution is created, and there is no contention for the GIL as there is no other thread around, so the main thread does not bother to acquire the lock. The GIL comes into play after other threads are spawned. The snippet in listing 7.3 is from the

Modules/_threadmodule.c and provides insight into this process during the creation of a new thread.

boot->interp = PyThreadState_GET()->interp;

boot->func = func;

boot->args = args;

boot->keyw = keyw;

boot->tstate = _PyThreadState_Prealloc(boot->interp);

if (boot->tstate == NULL) {

PyMem_DEL(boot);

return PyErr_NoMemory();

}

Py_INCREF(func);

Py_INCREF(args);

Py_XINCREF(keyw);

PyEval_InitThreads(); /* Start the interpreter's thread-awareness */

ident = PyThread_start_new_thread(t_bootstrap, (void*) boot);

The snippet in listing 7.3 is from the thread_PyThread_start_new_thread function that is invoked

to create a new thread. boot is a data structure the contains all the information that a new thread needs to execute. The tstate field references the thread state for the new thread, and the _PyThreadState_Prealloc function call creates this thread state. The main thread of execution

must acquire the GIL before creating the new thread; a call to PyEval_InitThreads handles this. With the interpreter now thread-aware

and the main thread holding the GIL, the PyThread_start_new_thread is invoked to create the new operating system thread.

The _tbootstrap function in the

Modules/_threadmodule.c module is a callback function invoked by new threads when they come alive. A snapshot of this bootstrap function is in listing 7.4.

static void t_bootstrap(void *boot_raw){

struct bootstate *boot = (struct bootstate *) boot_raw;

PyThreadState *tstate;

PyObject *res;

tstate = boot->tstate;

tstate->thread_id = PyThread_get_thread_ident();

_PyThreadState_Init(tstate);

PyEval_AcquireThread(tstate);

nb_threads++;

res = PyEval_CallObjectWithKeywords(

boot->func, boot->args, boot->keyw);

...

Notice the call to PyEval_AcquireThread function in listing 7.4. The PyEval_AcquireThread function

is defined in the Python/ceval.c module and it invokes the take_gil function, which is the function that attempts to get a hold of the GIL.

A description of this process, as provided in the source file, is quoted in the following text.

The GIL is just a boolean variable (gil_locked) whose access is protected by a mutex (gil_mutex), and whose changes are signalled by a condition variable (gil_cond). gil_mutex is taken for short periods of time, and therefore mostly uncontended. In the GIL-holding thread, the main loop (PyEval_EvalFrameEx) must be able to release the GIL on demand by another thread. A volatile boolean variable (gil_drop_request) is used for that purpose, which is checked at every turn of the eval loop. That variable is set after a wait of

intervalmicroseconds ongil_condhas timed out. [Actually, another volatile boolean variable (eval_breaker) is used which ORs several conditions into one. Volatile booleans are sufficient as inter-thread signalling means since Python is run on cache-coherent architectures only.] A thread wanting to take the GIL will first let pass a given amount of time (intervalmicroseconds) before setting gil_drop_request. This encourages a defined switching period, but does not enforce it since opcodes can take an arbitrary time to execute. Theintervalvalue is available for the user to read and modify using the Python APIsys.{get,set}switchinterval(). When a thread releases the GIL and gil_drop_request is set, that thread ensures that another GIL-awaiting thread gets scheduled. It does so by waiting on a condition variable (switch_cond) until the value of gil_last_holder is changed to something else than its own thread state pointer, indicating that another thread has taken GIL. This prohibits the latency-adverse behaviour on multi-core machines where one thread would speculatively release the GIL, but still, run and end up being the first to re-acquire it, making the “timeslices” much longer than expected.

What does the above mean for a newly spawned thread? The t_bootstrap function in listing 7.4

invokes the PyEval_AcquireThread function that handles requesting for the GIL. A lay explanation

for what happens during this request is thus - assume A is the main thread of execution holding the GIL while B is the new thread that has just been spawned.

- When

Bis spawned,take_gilis invoked. This checks if the conditionalgil_condvariable is set. If it is not set then the thread starts a wait. - After wait time elapses, the

gil_drop_requestis set. - Thread A, after each trip through the execution loop, checks if any other thread has set the

gil_drop_requestvariable. - Thread A drops the

GILwhen it detects that thegil_drop_requestvariable is set and also sets thegil_condvariable. - Thread A also waits on another variable -

switch_cond, until the value of thegil_last_holderis set to a value other than thread A’s thread state pointer indicating that another thread has taken theGIL. - Thread B now has the

GILand can go ahead to execute bytecode. - Thread A waits a given time, sets the

gil_drop_requestand the cycle continues.

To conclude this chapter, we recap the model of the Python virtual machine we have created so far that captures when we run the Python interpreter with a source file. First, the interpreter initializes interpreter and thread states, the source in the file is compiled into a code object. The code object is then passed to the interpreter loop where a frame object is created and attached to the main thread of execution, so the execution of the code object can happen. So we have a Python process that may contain one or more interpreter states, and each interpreter state may have one or more thread states, and each thread states references a frame that may reference another frame etc., forming a stack of frames. Figure 7.2 provides a visual representation of this order.

In the next chapter, we show how all the parts that we have described enable the execution of a Python code object.