5. Code Objects

Code objects are essential building blocks of the Python virtual machine. Code objects encapsulate the Python virtual machine’s bytecode; we may call the bytecode the assembly language of the Python virtual machine.

Code objects, as the name suggests, represent compiled executable Python code. We had come across code objects before when we discussed Python source compilation. The compilation process maps each code block to a code object. As described in the brilliant Python documentation:

A Python program is constructed from code blocks. A block is a piece of Python program text that is executed as a unit. The following are blocks: a module, a function body, and a class definition. Each command typed interactively is a block. A script file (a file given as standard input to the interpreter or specified as a command-line argument to the interpreter) is a code block. A script command (a command specified on the interpreter command line with the ‘-c’ option) is a code block. The string argument passed to the built-in functions

eval()andexec()is a code block.

The code object contains runnable bytecode instructions that alter the state of the Python VM when run. Given a function, we can access its code object using the

__code__ attribute as in the following snippet.

<code object return_author_name at 0x102279270, file "<stdin>", line 1>

For other code blocks, one can obtain the code objects for that code block by compiling such code. The compile function provides a facility for this in the Python interpreter. The code objects possess several fields that are used by the interpreter loop when executing and we look at some of these in the following sections.

5.1 Exploring code objects

An excellent way to start with code objects is to compile a simple function and inspect the resulting code object. We use the simple fizzbuzz function shown in Listing 5.2 as a guinea pig.

The fields shown are almost self-explanatory except for the co_lnotab and co_code fields that seem to contain gibberish.

-

co_argcount: This is the number of arguments to a code block and has a value only for function code blocks. The value is set to the count of the argument set of the code block’s

ASTduring the compilation process. The evaluation loop makes use of these variables during the set-up for code evaluation to carry out sanity checks such as checks that all arguments are present and for storing locals. -

co_code: This holds the sequence of bytecode instructions executed by the evaluation loop.

Each of these bytecode instruction sequences is composed of an

opcodeand anoparg- arguments to the opcode where it exists. For example,co.co_code[0]returns the first byte of the instruction,124that maps to a PythonLOAD_FASTopcode. -

co_consts: This field is a list of constants like string literals and numeric values contained within the code object. The example from above shows the content of this field for the

fizzbuzzfunction. The values included in this list are integral to code execution as they are the values referenced by theLOAD_CONSTopcode. The operand argument to a bytecode instruction such as theLOAD_CONSTis the index into this list of constants. Consider the co_consts value of(None, 3, 0, 5, 'FizzBuzz', 'Fizz', 'Buzz')for theFizzBuzzfunction and contrast with the disassembled code object below.Listing 5.3: Cross section of bytecode instructions for Fizzbuzz function 0 LOAD_BUILD_CLASS 2 LOAD_CONST 0 (<codeobjectTestat0x101a02810,file"fiz\zbuzz.py",line1>) 4 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Test') 6 MAKE_FUNCTION 0 8 LOAD_CONST 1 ('Test') 10 CALL_FUNCTION 2 12 STORE_NAME 0 (Test) ... 66 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (str) 68 LOAD_FAST 0 (n) 70 CALL_FUNCTION 1 72 RETURN_VALUE 74 LOAD_CONST 0 (None) 76 RETURN_VALUERecall that during the compilation process, a

return Noneis added if there is noreturnstatement at the end of a function so we can tell that the bytecode instruction at offset 74 is aLOAD_CONSTfor aNonevalue. The opcode argument is a 0, and we can see that theNonevalue has an index of0in the constants list from where theLOAD_CONSTinstruction loads it. - co_filename: This field, as the name suggests, contains the name of the file that contains the code object’s source code from which the code object.

- co_firstlineno: This gives the line number on which the source for the code object begins. This value plays quite an essential role during activities such as debugging code.

-

co_flags: This field indicates the kind of code object. For example, if the code object is that of a coroutine, the flag is set to

0x0080. Other flags such asCO_NESTEDindicate if a code object is nested within another code block,CO_VARARGSindicates if a code block has variable arguments. These flags affect the behaviour of the evaluation loop during bytecode execution. -

co_lnotab: The contains a string of bytes used to compute the source line numbers that correspond to instruction at a bytecode offset. For example, the

disthe function makes use of this when calculating line numbers for instructions. -

co_varnames: This is the collection of locally defined names in a code block. Contrast this with

co_names. -

co_names: This is the collection of non-local names used within the code object. For example, the snippet in listing 5.4 references a non-local variable,

p.Listing 5.4: Illustrating local and non-local names def test_non_local(): x = p + 1 return xList 5.5 is the result of introspecting on the code object for the function in Listing 5.4.

Listing 5.5: Illustrating local and non-local names co_argcount = 0 co_cellvars = () co_code = b't\x00d\x01\x17\x00}\x00|\x00S\x00' co_consts = (None, 1) co_filename = /Users/c4obi/projects/python_source/cpython/fizzbuzz.py co_firstlineno = 18 co_flags = 67 co_freevars = () co_kwonlyargcount = 0 co_lnotab = b'\x00\x01\x08\x01' co_name = test_non_local co_names = ('p',) co_nlocals = 1 co_stacksize = 2 co_varnames = ('x',)From this example, the difference between the

c_namesandco_varnamesis noticeable.co_varnamesreferences the locally defined names whileco_namesreferences non-locally defined names. Do note that it is only during execution of the program that an error is raised when the namepis not found. Listing 5.6 shows the bytecode instructions for the function in Listing 5.4, and it is an easy set to understand.Listing 5.6: Bytecode instructions for test_non_local function 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (0) 3 LOAD_CONST 1 (1) 6 BINARY_POWER 7 STORE_FAST 0 (0) 10 LOAD_FAST 0 (0) 13 RETURN_VALUENote how rather than a

LOAD_FASTas was seen in the previous example, we haveLOAD_GLOBALinstruction. Later, when we discuss the evaluation loop, we will discuss an optimisation that the evaluation loop carries out that makes the use of theLOAD_FASTinstruction as the name suggests. -

co_nlocals: This is a numeric value that represents the number of local names used by the code object. In the immediate past example from Listing 5.4, the only local variable used is

xand thus this value is1for the code object of that function. -

co_stacksize: The Python virtual machine is stack-based, i.e. values used in evaluation

and results of the evaluation are read from and written to an execution stack. This

co_stacksizevalue is the maximum number of items that exist on the evaluation stack at any point during the execution of the code block. -

co_freevars: The co_freevars field is a collection of free variables defined within the code block. This field is mostly relevant to nested functions that form closures.

Free variables are variables that are used within a block but not defined within that block;

this does not apply to global variables. The concept of a free variable is best illustrated with an example, as shown in listing 5.7.

Listing 5.7: A simple nested function deff(*args):x=1defg():n=xThe

co_freevarsfield is empty for the code object of theffunction while that of thegfunction contains thexvalue. Free variables are strongly interrelated with cell variables. -

co_cellvars: The

co_cellvarsfield is a collection of names for that require cell storage objects during the execution of a code object. Take the snippet in Listing 5.7, theco_cellvarsfield of the code object for the function -f, contains just the name -xwhile that of the nested function’s code object is empty; recall from the discussion on free variables that theco_freevarscollection of the nested function’s code object consists of just this name -x. This captures the relationship between cell variables, and free variables - a free variable in a nested scope is a cell variable within the enclosing scope. Special cell objects are required to store the values in this cell variable collection during the execution of the code object. This is so because each value in this field is used by nested code objects whose lifetime may exceed that of the enclosing code object. Hence, such values require storage in locations that do not get deallocated after the execution of the code object.

The bytecode - co_code in more detail.

The actual virtual machine instructions for a code object, the bytecode, are contained in the co_code

field of a code object as previously mentioned. The byte code from the fizzbuzz function, for example,

is the string of bytes shown in listing 5.7.

To get a human-readable version of the byte string, we use the dis function from the dis module

to extract a human-readable printout as shown in listing 5.8.

The first column of the output shows the line number for that instruction. Multiple instructions may

map to the same line number. This value is calculated using information from the co_lnotab field of a code object. The second column is the offset of the given instruction from the start of the bytecode.

Assuming the bytecode string is contained in an array, then this value is the index of the instruction into the array. The third column is the actual human-readable instruction

opcode; the full range of opcodes are found in the Include/opcode.h module. The fourth column is

the argument to the instruction.

The first LOAD_FAST instruction takes the argument 0. This value is an index into the co_varnames

array. The last column is the value of the argument - provided by the dis function for ease of use.

Some arguments do not take explicit arguments. Notice that the BINARY_MODULO and RETURN_VALUE

instructions take no explicit argument. Recall that the Python virtual machine is stack-based

so these instructions read values from the top of the stack.

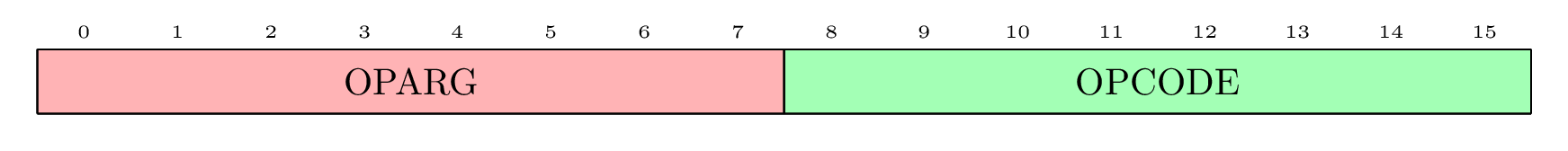

Bytecode instructions are two bytes in size - one byte for the opcode and the second byte for the argument to the opcode. In the case where the opcode does not take an argument, then the second argument byte is zeroed out. The Python virtual machine uses a little-endian byte encoding on the machine which I am currently typing out this book thus the 16 bits of code are structured as shown in figure 5.0 with the opcode taking up the higher 8 bits and the argument to the opcode taking up the lower 8 bits.

Sometimes, the argument to an opcode may be unable to fit into the default single byte.

The Python virtual machine makes use of the

EXTENDED_ARG opcode for these kinds of arguments. What the Python virtual machine does is to take an argument that is too

large to fit into a single byte and split it into two (we assume that it can fit into two bytes here, but this logic is easily extended past two bytes) - the most significant byte is an argument to the

EXTENDED_ARG opcode while the least significant byte is the argument to its actual opcode. The

EXTENDED_ARG opcode(s) will come before the actual opcode in the sequence of opcodes, and the argument

can then be rebuilt by shifts to the right and or’ing with other sections of the argument.

For example, if one wanted to pass the value 321 as an argument to the LOAD_CONST opcode, this value cannot fit into a single byte, so the EXTENDED_ARG opcode is used.

The binary representation of this value is 0b101000001, so the actual do work opcode (LOAD_CONST)

takes the first byte (1000001) as argument (65 in decimal) while the EXTENDED_ARG opcode takes the

next byte (1) as an argument; thus, we have (144, 1), (100, 65) as the sequence of instructions that is output.

The documentation for the dis module contains a comprehensive list and explanation of all opcodes currently implemented by the virtual machine.

5.2 Code Objects within other code objects

Another code block code object that is worth looking at is that of a module. Assuming

we are compiling a module with the fizzbuzz function as content, what would the output, look like?

To find out, we use the compile function in python to compile a module with the content shown in

listing 5.9.

Listing 5.10 is the result of compiling a module code block.

<code object f at 0x102a028a0, file "fizzbuzz.py",\

line 1>)

2 LOAD_CONST 1 ('f')

4 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

6 STORE_NAME 0 (f)

8 LOAD_CONST 2 (None)

10 RETURN_VALUE

The instruction at byte offset 0 loads a code object stored as the name f - our function definition

using the MAKE_FUNCTION Instruction. Listing 5.11 is the content of this code object.

<code object f at 0x1022029c0, file "fizzbuzz.py", line 1>, 'f', No\

ne)

co_filename = fizzbuzz.py

co_firstlineno = 1

co_flags = 64

co_freevars = ()

co_kwonlyargcount = 0

co_lnotab = b''

co_name = <module>

co_names = ('f',)

co_nlocals = 0

co_stacksize = 2

co_varnames = ()

As would be expected in a module, the fields related to code object arguments are all zero

- (co_argcount, co_kwonlyargcount). The co_code field contains bytecode instructions, as shown in listing 5.10. The co_consts field is an interesting one. The constants in the field are a code object and the names - f and None. The code object is that of the function, the value ‘f’ is the name of the function, and None is the return value of the function - recall the python compiler adds a return None statement to a code object without one.

Notice that function objects are not created during the module’s compilation. What we have are just code objects - it is during the execution of the code objects that the function gets created as seen in Listing 5.10. Inspecting the attributes of the code object will show that it is also composed of other code objects as shown in listing 5.12.

<code object g at 0x101a028a0, file "fizzbuzz.py", line\

5>, 'f.<locals>.g')

co_filename = fizzbuzz.py

co_firstlineno = 1

co_flags = 3

co_freevars = ()

co_kwonlyargcount = 0

co_lnotab = b'\x00\x01\x08\x01\x04\x01\x04\x01'

co_name = f

co_names = ('print', 'c')

co_nlocals = 1

co_stacksize = 3

co_varnames = ('g',)

The same logic explained earlier on applies here with the function object created only during the execution of the code object.

5.3 Code Objects in the VM

Like most built-in types, there is the code type that defines the code object type

and the PyCodeObject structure for code objects instances. The code type is similar to other type objects that have been discussed in previous sections, so we do not reproduce it here. Listing 5.13 shows the structures used to represent code objects instances.

typedef struct {

PyObject_HEAD

int co_argcount; /* #arguments, except *args */

int co_kwonlyargcount; /* #keyword only arguments */

int co_nlocals; /* #local variables */

int co_stacksize; /* #entries needed for evaluation stack */

int co_flags; /* CO_..., see below */

int co_firstlineno; /* first source line number */

PyObject *co_code; /* instruction opcodes */

PyObject *co_consts; /* list (constants used) */

PyObject *co_names; /* list of strings (names used) */

PyObject *co_varnames; /* tuple of strings (local variable names) */

PyObject *co_freevars; /* tuple of strings (free variable names) */

PyObject *co_cellvars; /* tuple of strings (cell variable names) */

unsigned char *co_cell2arg; /* Maps cell vars which are arguments. */

PyObject *co_filename; /* unicode (where it was loaded from) */

PyObject *co_name; /* unicode (name, for reference) */

PyObject *co_lnotab; /* string (encoding addr<->lineno mapping) See

Objects/lnotab_notes.txt for details. */

void *co_zombieframe; /* for optimization only (see frameobject.c) */

PyObject *co_weakreflist; /* to support weakrefs to code objects */

/* Scratch space for extra data relating to the code object.__icc_nan

Type is a void* to keep the format private in codeobject.c to force

people to go through the proper APIs. */

void *co_extra;

} PyCodeObject;

The fields are almost all the same as those found in a Python code objects except for the co_stacksize,

co_flags, co_cell2arg, co_zombieframe, co_weakreflist and co_extra. co_weakreflist and

co_extra are not really interesting fields at this point. The rest of the fields here pretty much serve the same purpose as those in the code object. The co_zombieframe is a field that exists for optimisation purposes. It holds a reference to a frame object that was previously used as a context

to execute the code object. This is then used as the execution frame when such code object is being re-executed

to prevent the overhead of allocating memory for another frame object.