9. The evaluation loop, ceval.c

We have finally arrived at the gut of the virtual machine where the virtual machine iterates over a code object’s bytecode instructions and executes such instructions. The essence of this is a for loop that iterates over opcodes, switching on each opcode type to run the desired code. The Python/ceval.c

module, about 5411 lines long, implements most of the functionality required - at the heart of this function is the PyEval_EvalFrameEx function, an approximately 3000 line long function that contains

the actual evaluation loop. It is this PyEval_EvalFrameEx function that is the main thrust of our focus in the chapter.

The Python/ceval.c module provides platform-specific optimizations such as threaded gotos as well as Python virtual machine optimizations such as opcode prediction. In this

write-up, we are more concerned with the virtual machine processes and optimizations, so we conveniently

disregard any platform-specific optimizations or process introduced here so long as it does not take away from our explanation of the evaluation loop. We go into more detail than usual here to provide a solid explanation for how the heart of the virtual machine is structured and works. It is important

to note that the opcodes and their implementations are constantly in flux so this description here may be inaccurate at a later time.

Before any bytecode execution happens, several housekeeping operations such as creating and initializing frames, setting up variables and initializing the virtual machine variables such as instruction pointers are carried out. We look at some of these operations next.

9.1 Putting names in place

As mentioned above, the heart of the virtual machine is the PyEval_EvalFrameEx function that executes the Python bytecode but before this happens, a lot of setups -

error checking, frame creation and initialization etc. - need to take place to prepare the evaluation context. This is where the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName function also within the Python/ceval.c

the module comes in. For illustration purposes,

we assume that we are working with a module that has the content shown in listing 9.0.

def test(arg, defarg="test", *args, defkwd=2, **kwd):

local_arg = 2

print(arg)

print(defarg)

print(args)

print(defkwd)

print(kwd)

test()

Recall that code blocks have code objects; these code blocks could either be functions,

modules etc. so for a module with the above content, we can safely assume that we are

dealing with two code objects - one for the module and one for the function test defined within

the module.

After the generation of the code object for the module in listing 9.0, the generated code object is

executed via a chain of function calls from the Python/pythonrun.c module - run_mod -> PyEval_EvalCode->PyEval_EvalCodeEx->_PyEval_EvalCodeWithName->PyEval_EvalFrameEx.

At this moment, our interest lies with the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName function with its signature

shown in listing 9.1. It handles the required name setup before bytecode

evaluation in PyEval_EvalFrameEx.

However, by looking at the function signature for the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName as shown in listing 9.1,

one is probably left asking how this is related to executing a module object rather than an actual function.

static PyObject * _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName(PyObject *_co, PyObject *globals, PyO\

bject *locals,

PyObject **args, int argcount, PyObject **kws, int kwcount,

PyObject **defs, int defcount, PyObject *kwdefs, PyObject *closure,

PyObject *name, PyObject *qualname)

To wrap one’s head around this, one must think more generally in terms of code blocks and code objects, not functions or modules. Code blocks can have any or none of those arguments specified in the

_PyEval_EvalCodeWithName function signature - a function

just happens to be a more specific type of code block which has most if not all those values supplied.

This means that the case of executing _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName for a module code object is not very interesting as most of those arguments are without value. The interesting instance occurs when a Python function call is made via the CALL_FUNCTION opcode. This results in a call to the fast_function

function also in the Python/ceval.c module. This function extracts function arguments

from the function object before delegating to the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName function to carry out

all the sanity checks that are needed - this is not the full story, but we will look at the CALL_FUNCTION

opcode in more detail in a later section of this chapter.

The _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName is quite a big function, so we do not include it here, but most of the setup process that it goes through is pretty straightforward. For example, recall we mentioned that the fastlocals field of a frame object provides some optimization for the local namespace and that non-positional function arguments are known fully only at runtime. This means that we cannot populate this fastlocals data structure without careful error checking. It is during this setup by the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName function that the array referenced by the fastlocals field of a frame is populated with the full range of local values.

The steps involved in the setup process that the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName goes through when called involves the steps shown in listing 9.1.

9.2 The parts of the machine

With all the names in place, PyEval_EvalFrameEx is invoked with a frame object as one of its arguments. A cursory look at this function shows that the function is composed of quite a few

C macros and variables. The macros are an integral part of the execution loop - they provide a means to abstract away repetitive code without incurring the cost of a function call and as such we describe a few of them. In this section, we assume that the virtual machine is not running with C optimizations such as computed gotos enabled so we conveniently ignore macros related to such optimizations.

We begin with a description of some of the variables that are crucial to the execution of the evaluation loop.

-

**stack_pointer: refers to the next free slot in the value stack of the execution frame.

-

*next_instr: refers to the next instruction to be executed by the evaluation loop. One can think of this as the program counter for the virtual machine. Python 3.6 changes the type of this value to anunsigned shortwhich is 2 bytes in size to handle the new bytecode instruction size. -

opcode: refers to the currently executing python opcode or the opcode that is about to be executed. -

oparg: refers to the argument of the presently executing opcode or opcode that is about to be executed if it takes an argument. -

why: The evaluation loop is an infinite loop implemented by the infiniteforloop -for(;;)so the loop needs a mechanism to break out of the loop and specify why the break occurred. This value refers to the reason for an exit from the evaluation loop. For example if the code block exited the loop due to a return statement, then this value will contain aWHY_RETURNstatus. -

fastlocals: refers to an array of locally defined names. -

freevars: refers to a list of names that are used within a code block but not defined in that code block. -

retval: refers to the return value from executing the code block. -

co: References the code object that contains the bytecode that will be executed by the evaluation loop. -

names: This references the names of all values in the code block of the executing frame. -

consts: This references the constants used by the code objects.

The following macros play a vital role in the evaluation loop.

-

TARGET(op): expands to thecase opstatement. This matches the current opcode with the block of code that implements the opcode. -

DISPATCH: expands tocontinue. This together with the next macro -FAST_DISPATCH, handle the flow of control of the evaluation loop after an opcode is executed. -

FAST_DISPATCH: expands to a jump to thefast_next_opcodelabel within the evaluationforloop.

With the introduction of the standard 2 bytes opcode in Python 3.6, the following set of macros are used to handle code access.

-

INSTR_OFFSET(): This macro provides the byte offset of the current instruction into the array of instructions. This expands to(2*(int)(next_instr - first_instr)). -

NEXTOPARG(): This updates theopcodeandopargvariable to the value of the opcode and argument of the next bytecode instruction to be executed. This macro expands to the following snippet.

NEXTOPARG macrodo { \

unsigned short word = *next_instr; \

opcode = OPCODE(word); \

oparg = OPARG(word); \

next_instr++; \

} while (0)

The OPCODE and OPARG macros handle the bit manipulation for extracting opcode and arguments.

Figure 9.0 shows the structure of a bytecode instruction with the argument to the opcode taking lower

eight bits and the opcode itself taking the upper eight bits hence OPCODE expands to ((word) & 255)

thus extracting the most significant byte from the bytecode instruction while OPARG which expands

to ((word) >> 8) extracts the least significant byte.

-

JUMPTO(x): This macro expands to(next_instr = first_instr + (x)/2)and performs an absolute jump to a particular offset in the bytecode stream. -

JUMPBY(x): This macro expands to(next_instr += (x)/2)and performs a relative jump from the current instruction offset to another point in the bytecode instruction stream. -

PREDICT(op): This opcode together with thePREDICTED(op)opcode implement the Python evaluation loop opcode prediction. This opcode expands to the following snippet.Listing 9.4: Expansion of the PREDICT(op)macrodo{\unsignedshortword=*next_instr;\opcode=OPCODE(word);\if(opcode==op){\oparg=OPARG(word);\next_instr++;\gotoPRED_##op;\}\}while(0) -

PREDICTED(op): This macro expands toPRED_##op:.

The last two macros defined above handle opcode prediction. When the evaluation loop encounters a

PREDICT(op) macro; the interpreter assumes that the next instruction to be executed is op. The macros check that this is indeed valid and if valid fetches the actual opcode and argument then jumps to the label PRED_##op where the ## is a placeholder for the actual opcode.

For example, if we had encountered a prediction such as PREDICT(LOAD_CONST) then the

goto statement argument would be PRED_LOAD_CONSTop if that prediction was valid. An inspection of

the source code for the PyEval_EvalFrameEx function finds the PREDICTED(LOAD_CONST) label that expands to PRED_LOAD_CONSTop so on a successful prediction of this instruction; there is a jump to

this label otherwise normal execution continues. This prediction saves the cost involved with the extra traversal of the switch statement that would otherwise happen with normal code execution.

The next set of macros that we are interested in are the stack manipulation macros that handle placing and fetching of values from the value stack of a frame object. These macros are pretty similar, and the following snippet shows a few examples.

-

STACK_LEVEL(): This returns the number of items on the stack. The macro expands to((int)(stack_pointer - f->f_valuestack)). -

TOP(): The returns the last item on the stack. This expands to(stack_pointer[-1]). -

SECOND(): This returns the penultimate item on the stack. This expands to(stack_pointer[-2]). -

BASIC_PUSH(v): This places the item, v, on the stack. It expands to(*stack_pointer++ = (v)). A current alias for this macro is thePUSH(v). -

BASIC_POP(): This removes and returns an item from the stack. This expands to(*--stack_pointer). A current alias for this is thePOP()macro.

The last set of macros of concern to us are those that handle local variable manipulation. These macros,

GETLOCAL and SETLOCAL are used to get and set values in the fastlocals array.

-

GETLOCAL(i): This expands to(fastlocals[i]). This handles the fetching of locally defined names from the local array. -

SETLOCAL(i, value): This expands to the snippet in listing 9.5. This macro sets theithelement of the local array to the supplied value.Listing 9.5: Expansion of the SETLOCAL(i, value)macrodo{PyObject*tmp=GETLOCAL(i);\GETLOCAL(i)=value;\Py_XDECREF(tmp);}while(0)

The UNWIND_BLOCK and UNWIND_EXCEPT_HANDLER are related to exception handling, and we look at them

in subsequent sections.

9.3 The Evaluation loop

We have finally come to the heart of the virtual machine - the loop where the opcodes are evaluated. The implementation is pretty anti-climatic as there is nothing special here, just a never-ending for loop and a massive switch statement that matches on opcodes.

To get a concrete understanding of this statement, we look at the execution of the simple hello world function in listing 9.6.

def hello_world():

print("hello world")

Listing 9.7 shows the disassembly of the function from Listing 9.6, and we illustrate the evaluation of this set of instructions.

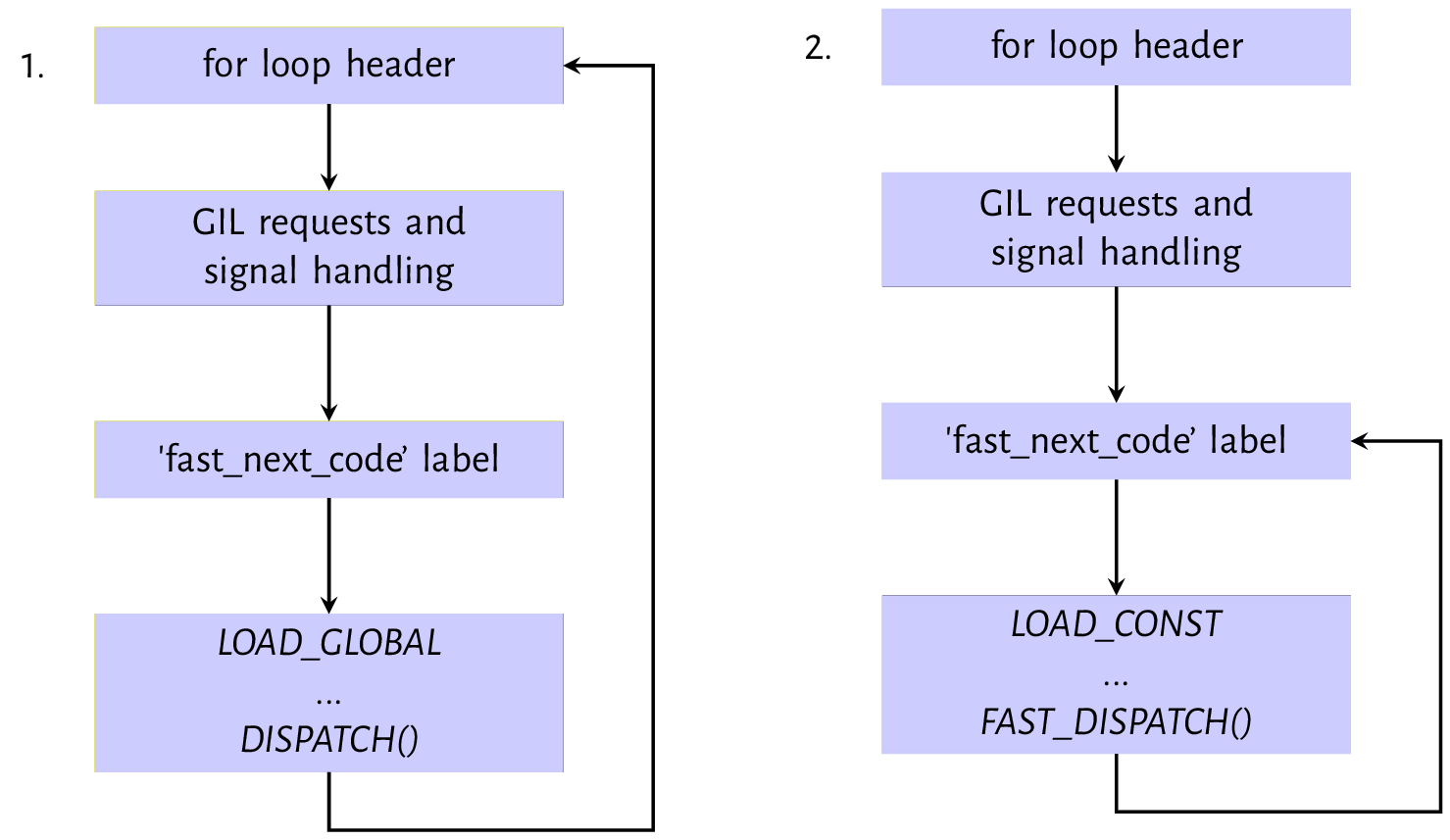

LOAD_GLOBAL and LOAD_CONST instructionsFigure 9.1 shows the evaluation path for the LOAD_GLOBAL and LOAD_CONST instructions. The second

and third blocks in both images of figure 9.2 represent the housekeeping tasks performed on

every iteration of the evaluation loop. TheGIL and signal handling checks were discussed in the

the previous chapter on interpreter and thread states - it is during these checks that a thread executing

may give up control of the GIL for another thread to execute. The fast_next_opcode is a code label

just after the GIL and signal handling code

that exists to serve as a jump destination when the loop wishes to skip the previous checks as we will

see when we look at the LOAD_CONST instruction.

The first instruction - LOAD_GLOBAL is evaluated by the LOAD_GLOBAL case statement of the switch statement.

The implementation of this opcode like other opcodes is a series of C statements and function calls that are surprisingly involved, as shown in listing 9.8. The implementation of the opcode loads the value

identified by the given name from the global or builtin namespace onto the evaluation stack. The

oparg is the index into the tuple which contains all names used within the code block - co_names.

PyObject *name = GETITEM(names, oparg);

PyObject *v;

if (PyDict_CheckExact(f->f_globals)

&& PyDict_CheckExact(f->f_builtins)){

v = _PyDict_LoadGlobal((PyDictObject *)f->f_globals,

(PyDictObject *)f->f_builtins,

name);

if (v == NULL) {

if (!_PyErr_OCCURRED()) {

/* _PyDict_LoadGlobal() returns NULL without raising

* an exception if the key doesn't exist */

format_exc_check_arg(PyExc_NameError,

NAME_ERROR_MSG, name);

}

goto error;

}

Py_INCREF(v);

}

else {

/* Slow-path if globals or builtins is not a dict */

/* namespace 1: globals */

v = PyObject_GetItem(f->f_globals, name);

if (v == NULL) {

if (!PyErr_ExceptionMatches(PyExc_KeyError))

goto error;

PyErr_Clear();

/* namespace 2: builtins */

v = PyObject_GetItem(f->f_builtins, name);

if (v == NULL) {

if (PyErr_ExceptionMatches(PyExc_KeyError))

format_exc_check_arg(

PyExc_NameError,

NAME_ERROR_MSG, name);

goto error;

}

}

}

The look-up algorithm for the LOAD_GLOBAL opcode first attempts to load the name from the f_globals

and f_builtins fields if they are dict objects otherwise it attempts to fetch the value associated with the name from the f_globals or f_builtins object with the assumption that they implement some

protocol for fetching the value associated with a given name.

The value, if found, is loaded on to the evaluation stack using the PUSH(v) instruction otherwise, an error is set, and the execution jumps to the label for handling that error code.

As the flow chart shows, the DISPATCH() macro, an alias for the continue statement, is called after the value is pushed onto the evaluation stack.

The second diagram, labelled 2 in figure 9.1, shows the execution of the LOAD_CONST. Listing 9.9 is an implementation of the LOAD_CONST opcode.

LOAD_CONST opcode implementationPyObject *value = GETITEM(consts, oparg);

Py_INCREF(value);

PUSH(value);

FAST_DISPATCH();

This goes through the standard setup as LOAD_GLOBAL but after execution, FAST_DISPATCH() is called

rather than DISPATCH(). This causes a jump to the fast_next_opcode code label from where the loop

execution continues skipping the signal and GIL checks on the next iteration. Opcodes that have

implementations that make C function calls make of the DISPATCH macro while opcodes like the

LOAD_GLOBAL that does not make C function calls in their implementation make use of the FAST_DISPATCH

macro. This means that the thread of execution can only yield the GIL after executing opcodes that make C function calls.

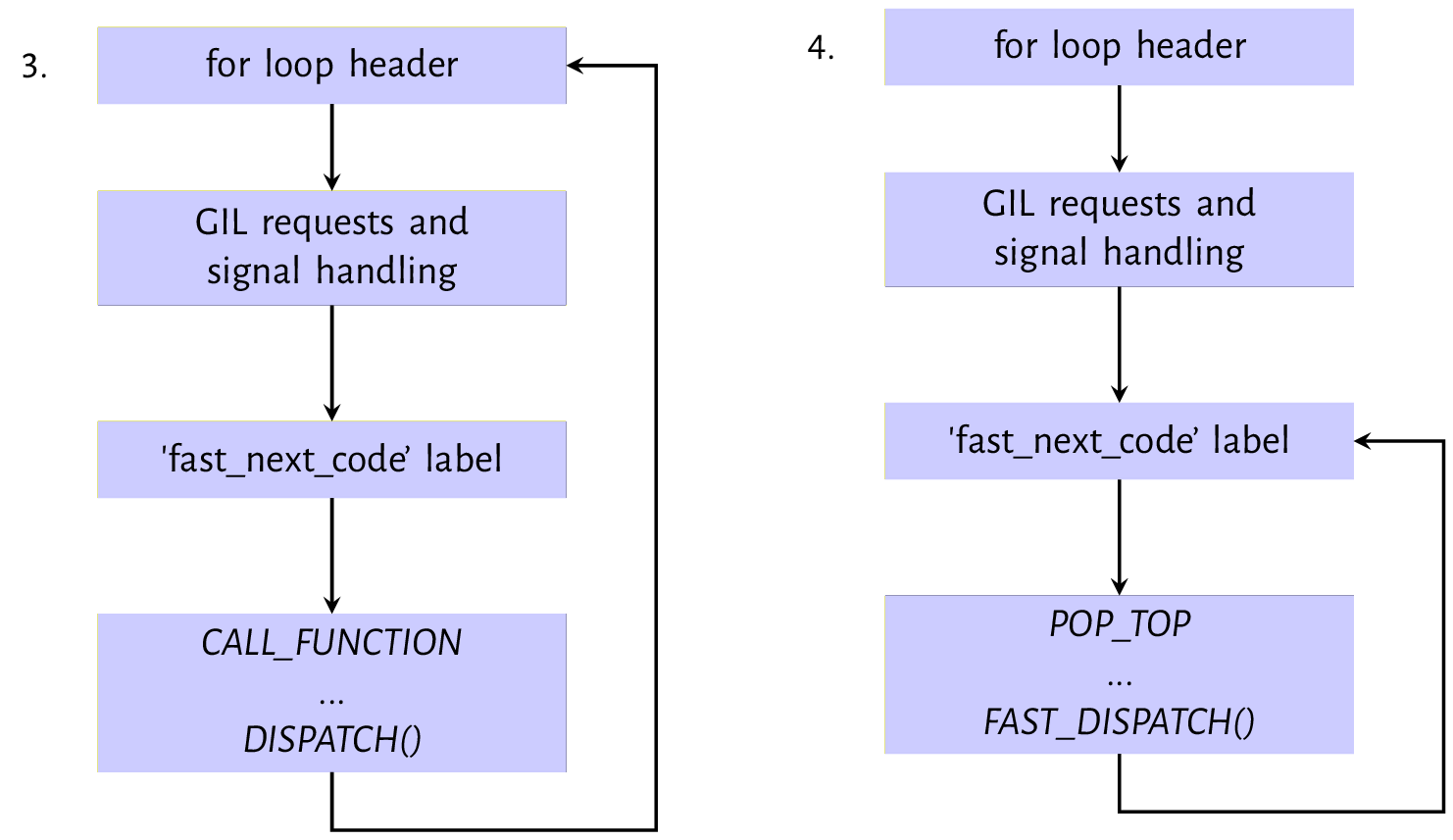

CALL_FUNCTION and POP_TOP instructionThe next instruction is the CALL_FUNCTION opcode, as shown in the first image from figure 9.2.

The compile emits this opcode for a function call with only positional arguments. Listing 9.10 is the implementation for this opcode.

At the heart of the opcode implementation is the call_function(&sp, oparg, NULL). oparg is the number of arguments passed to the function, and the call_function function reads that number of values from the evaluation stack.

CALL_FUNCTION opcode implementationPyObject **sp, *res;

PCALL(PCALL_ALL);

sp = stack_pointer;

res = call_function(&sp, oparg, NULL);

stack_pointer = sp;

PUSH(res);

if (res == NULL) {

goto error;

}

DISPATCH();

The next instruction shown in diagram 4 of figure 9.2 is the POP_TOP instruction that removes a single

value from the top of the evaluation stack - this

clears any value placed on the stack by the previous function call.

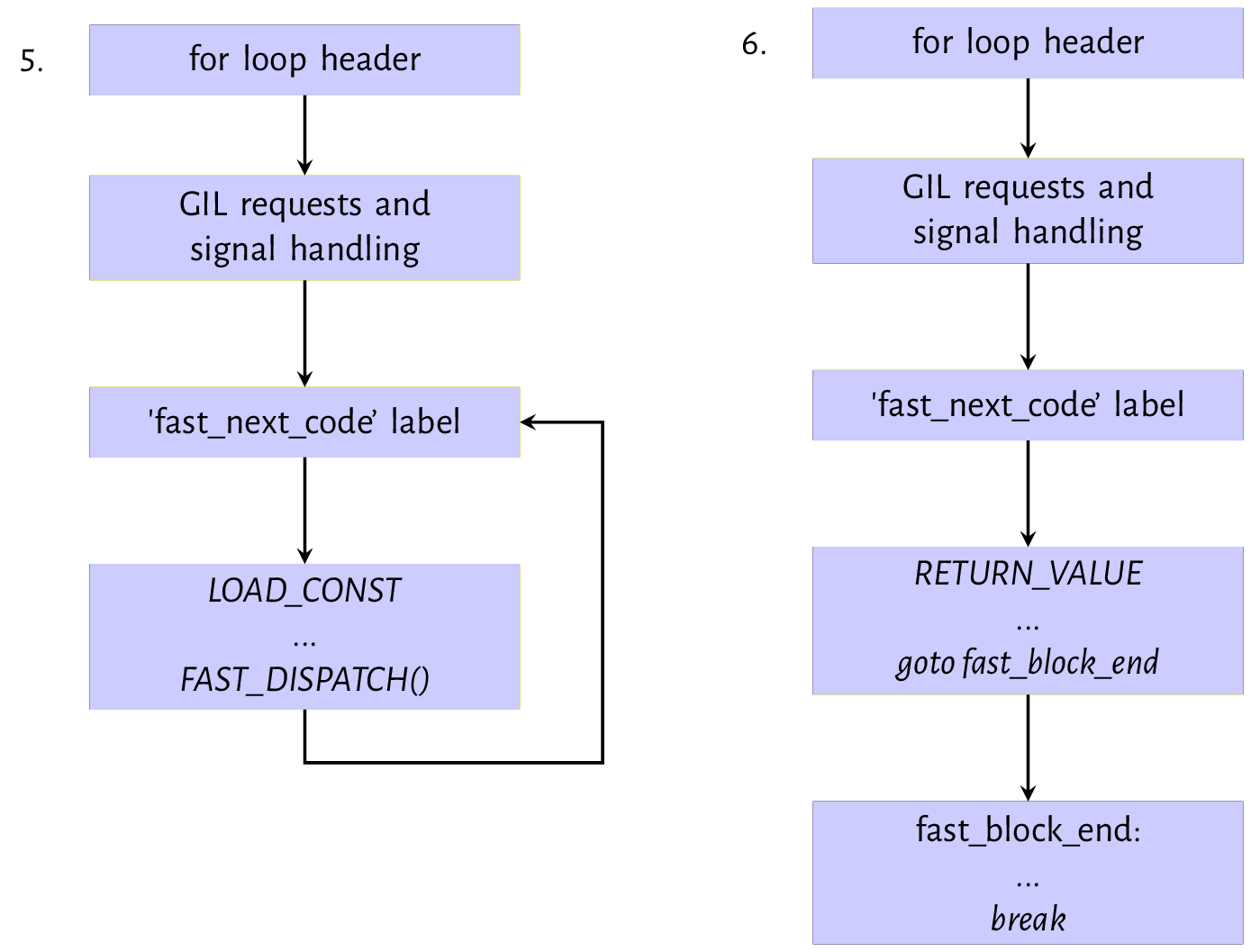

LOAD_CONST and RETURN_VALUE instructionThe next set of instructions are the LOAD_CONST and RETURN_VALUE pair shown in diagrams 5 and 6

of figure 9.3. The LOAD_CONST opcode loads a None value onto the evaluation stack; this is the value that the RETURN_VALUE will return. These two always go together when

a function does not explicitly return any value. We

have already looked at the mechanics of the LOAD_CONST instruction. The RETURN_VALUE instruction pops the top of the stack into the retval variable, sets the WHY status code to WHY_RETURN and then performs a jump to the fast_block_end code label where the execution continues. If there has been no exception, the execution breaks out of the for loop and returns the retval.

Notice that a lot of the code snippets that we have looked at have the goto error jump, but we have intentionally discussing errors and exceptions

out so far. We will look at exception handling in the next chapter. Although the function’s bytecode looked at in this section is relatively trivial, it encapsulates the vanilla behaviour of the evaluation loop. Other opcodes may have more complicated implementations, but the essence of the execution is the same as described above.

Next, we look at some other interesting opcodes supported by the python virtual machine.

9.4 A sampling of opcodes

The python virtual machine has about 157 opcodes, so we randomly pick a few opcodes and de-construct to get more of a feel for how these opcodes function. Some examples of these opcodes include:

-

MAKE_FUNCTION: As the name suggests, the opcode creates a function object from values on the evaluation stack. Consider a module containing the functions shown in listing 9.11.Listing 9.11: Function definitions in a module deftest_non_local(arg,*args,defarg="test",defkwd=2,**kwd):local_arg=2print(arg)print(defarg)print(args)print(defkwd)print(kwd)defhello_world():print("Hello world!")Disassembly of the code object from the module’s compilation gives the set of bytecode instructions shown in listing 9.12

Listing 9.11: Disassembly of code object from listing 9.11 170LOAD_CONST8(('test',))2LOAD_CONST1(2)4LOAD_CONST2(('defkwd',))6BUILD_CONST_KEY_MAP18LOAD_CONST3(<codeobjecttest_non_localat0x109eead0\0,file"string",line17>)10LOAD_CONST4('test_non_local')12MAKE_FUNCTION314STORE_NAME0(test_non_local)4516LOAD_CONST5(<codeobjecthello_worldat0x109eeae80,\file"string",line45>)18LOAD_CONST6('hello_world')20MAKE_FUNCTION022STORE_NAME1(hello_world)24LOAD_CONST7(None)26RETURN_VALUEWe can see that the

MAKE_FUNCTIONopcode appears twice in the series of bytecode instructions - one for each function definition within the module. The implementation of theMAKE_FUNCTIONcreates a function object and then stores the function in thelocalnamespace using the function definition name. Notice that default arguments are pushed on the stack when such arguments are defined. TheMAKE_FUNCTIONimplementation consumes these values by and’ing theopargwith a bitmask and popping values from the stack accordingly.Listing 9.12: MAKE_FUNCTIONopcode implementationTARGET(MAKE_FUNCTION){PyObject*qualname=POP();PyObject*codeobj=POP();PyFunctionObject*func=(PyFunctionObject*)PyFunction_NewWithQualName(codeobj,f->f_globals,qualname);Py_DECREF(codeobj);Py_DECREF(qualname);if(func==NULL){gotoerror;}if(oparg&0x08){assert(PyTuple_CheckExact(TOP()));func->func_closure=POP();}if(oparg&0x04){assert(PyDict_CheckExact(TOP()));func->func_annotations=POP();}if(oparg&0x02){assert(PyDict_CheckExact(TOP()));func->func_kwdefaults=POP();}if(oparg&0x01){assert(PyTuple_CheckExact(TOP()));func->func_defaults=POP();}PUSH((PyObject*)func);DISPATCH();}The flags above denote the following.

-

0x01: a tuple of default argument objects in positional order is on the stack. -

0x02: a dictionary of keyword-only parameters default values is on the stack. -

0x04: an annotation dictionary is on the stack. -

0x08: a tuple containing cells for free variables, making a closure is on the stack.

The

PyFunction_NewWithQualNamefunction that actually creates a function object is implemented in theObjects/funcobject.cmodule and its implementation is pretty simple. The function initializes a function object and sets values on the function object. -

-

LOAD_ATTR: This opcode handles attribute references such asx.y. Assuming we have an instance objectx, an attribute reference such asx.nametranslates to the set of opcodes shown in listing 9.13.Listing 9.13: Opcodes for an attribute reference 24 LOAD_NAME 1 (x) 26 LOAD_ATTR 2 (name) 28 POP_TOP 30 LOAD_CONST 4 (None) 32 RETURN_VALUEThe

LOAD_ATTRopcode implementation is pretty simple and shown in listing 9.14.Listing 9.14: LOAD_ATTRopcode implementationTARGET(LOAD_ATTR){PyObject*name=GETITEM(names,oparg);PyObject*owner=TOP();PyObject*res=PyObject_GetAttr(owner,name);Py_DECREF(owner);SET_TOP(res);if(res==NULL)gotoerror;DISPATCH();}We have looked at the

PyObject_GetAttrfunction in the chapter on objects. This function returns the value of an object’s attribute which is then loaded on to the stack. One can review the chapter on objects to get the details on how this function works. -

CALL_FUNCTION_KW: This opcode very similar in functionality to theCALL_FUNCTIONopcode that was discussed previously but is used for function calls with keyword arguments. Listing 9.15 is the implementation for this opcode. Notice how one of the significant change from the implementation of theCALL_FUNCTIONopcode is that a tuple of names is now passed as one of the arguments whencall_functionis invoked.Listing 9.15: CALL_FUNCTION_KWopcode implementationPyObject**sp,*res,*names;names=POP();assert(PyTuple_CheckExact(names)&&PyTuple_GET_SIZE(names)<=oparg);PCALL(PCALL_ALL);sp=stack_pointer;res=call_function(&sp,oparg,names);stack_pointer=sp;PUSH(res);Py_DECREF(names);if(res==NULL){gotoerror;}

The names are the keyword arguments of the function call, and they are used in the _PyEval_EvalCodeWithName

to handle the setup before the code object for the function is executed.

This caps our explanation of the evaluation loop. As we have seen, the concepts behind the evaluation loop are not complicated - opcodes each have implementations that in C. These implementations are the actual do work functions. Two critical areas that we have not touched are exception handling and the block stack, two intimately related concepts that we look at in the following chapter.