4. Python Objects

In this chapter, we look at the Python objects and their implementation in the CPython virtual machine. This is central to understanding the Python virtual machine’s internals. Most of the source referenced in this chapter is available in the Include/ and Objects/ directories. Unsurprisingly, the implementation of the Python object system is quite complex, so we try to avoid getting bogged down in the gory details of the C implementation. To kick this off, we start by looking at the PyObject structure - the workhorse of the Python object system.

4.1 PyObject

A cursory inspection of the CPython source code reveals the ubiquity of the PyObject structure. As we will see later on in this treatise, all the value stack objects used by the interpreter during evaluation are PyObjects.

For want of a better term, we refer to this as the superclass of all

Python objects. Values are never declared as PyObject but a pointer to any object can be cast to a PyObject. In layman’s term, any object can be treated as a PyObject structure because the initial

segment of all objects is a PyObject structure.

Listing 4.0 is a definition of the PyObject structure. This structure is composed of several fields that must be

filled for a value to be treated as an object.

1 typedef struct _object {

2 _PyObject_HEAD_EXTRA

3 Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt;

4 struct _typeobject *ob_type;

5 } PyObject;

The _PyObject_HEAD_EXTRA when present is a C macro that defines fields that point to the previously allocated

object and the next object, thus forming an implicit doubly-linked list of all live objects.

The ob_refcnt field is for memory management, while the *ob_type is a pointer to the type object for the given object. This type determines what the data represents, what kind of data it contains, and the kind of operations the object supports. Take the snippet in Listing 4.1 for example, the name, name, points to a string object, and the type of the object is “str”.

1 >>> name = 'obi'

2 >>> type(name)

3 <class 'str'>

A valid question from here is if the type field points to a type object then what does the *ob_type field of that type object point to? The ob_type for a type object recursively refers to itself hence the saying that the type of a type is type.

Types in the VM are implemented using the _typeobject data structure defined in the Objects/Object.h

module. This is a C struct with fields for mostly functions or collections of functions filled in by each type. We look at this data structure next.

4.2 Dissecting Types

The _typeobject structure defined in Include/Object.h serves as the base structure of all

Python types. The data structure defines a large number of fields that are mostly pointers to C functions

that implement some functionality for a given type. Listing 4.2 is the _typeobject structure definition.

1 typedef struct _typeobject {

2 PyObject_VAR_HEAD

3 const char *tp_name; /* For printing, in format "<module>.<name>" */

4 Py_ssize_t tp_basicsize, tp_itemsize; /* For allocation */

5

6 destructor tp_dealloc;

7 printfunc tp_print;

8 getattrfunc tp_getattr;

9 setattrfunc tp_setattr;

10 PyAsyncMethods *tp_as_asyn;

11

12 reprfunc tp_repr;

13

14 PyNumberMethods *tp_as_number;

15 PySequenceMethods *tp_as_sequence;

16 PyMappingMethods *tp_as_mapping;

17

18 hashfunc tp_hash;

19 ternaryfunc tp_call;

20 reprfunc tp_str;

21 getattrofunc tp_getattro;

22 setattrofunc tp_setattro;

23

24 PyBufferProcs *tp_as_buffer;

25 unsigned long tp_flags;

26 const char *tp_doc; /* Documentation string */

27

28 traverseproc tp_traverse;

29

30 inquiry tp_clear;

31 richcmpfunc tp_richcompare;

32 Py_ssize_t tp_weaklistoffset;

33

34 getiterfunc tp_iter;

35 iternextfunc tp_iternext;

36

37 struct PyMethodDef *tp_methods;

38 struct PyMemberDef *tp_members;

39 struct PyGetSetDef *tp_getset;

40 struct _typeobject *tp_base;

41 PyObject *tp_dict;

42 descrgetfunc tp_descr_get;

43 descrsetfunc tp_descr_set;

44 Py_ssize_t tp_dictoffset;

45 initproc tp_init;

46 allocfunc tp_alloc;

47 newfunc tp_new;

48 freefunc tp_free;

49 inquiry tp_is_gc;

50 PyObject *tp_bases;

51 PyObject *tp_mro;

52 PyObject *tp_cache;

53 PyObject *tp_subclasses;

54 PyObject *tp_weaklist;

55 destructor tp_del;

56

57 unsigned int tp_version_tag;

58 destructor tp_finalize;

59 } PyTypeObject;

The PyObject_VAR_HEAD field is an extension of the PyObject field discussed in the previous section; this extension adds an

ob_size field for objects that have the notion of length. The Python C API documentation contains a description of each of the fields in this object structure. The critical thing

to note is that the fields in the structure each implement a part of the type’s behavior. Most of these fields are part of what we can call an object interface or protocol; the types implement these functions but in a type-specific way.

For example, tp_hash field is a reference to a hash function for a given type - this

field could be left without a value in the case where instances of the type are not hashable;

whatever function is in the tp_hash field gets invoked when the hash method is called on an instance of that

type. The type object also has the field - tp_methods that references methods unique to that type.

The tp_new slot refers to a function that creates new instances of the type and so

on. Some of these fields, such as tp_init, are optional - not every type needs to run an initialization function, especially when the type is immutable, such as tuples. In contrast, other fields, such as tp_new, are compulsory.

Also, among these fields are fields for other Python protocols, such as the following.

- Number protocol - A type implementing this protocol will have implementations for the

PyNumberMethods *tp_as_numberfield. This field is a reference to a set of functions that implement arithmetic operations (this does not necessarily have to be on numbers). A type will support arithmetic operations with their corresponding implementations included in thetp_as_numberset in the type’s specific way. For example, the non-numericsettype has an entry into this field because it supports arithmetic operations such as-,<=, and so on. - Sequence protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

PySequenceMethods *tp_as_sequencefield. This value should provide that type with support for some sequence operations such aslen,inetc. - Mapping protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

PyMappingMethods *tp_as_mapping. This value enables such type to be treated like Python dictionaries using the dictionary syntax for setting and accessing key-value mappings. - Iterator protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

getiterfunc tp_iterand possibly theiternextfunc tp_iternextfields enabling instances of the type to be used like Python iterators. - Buffer protocol - A type implementing this protocol will have a value in the

PyBufferProcs *tp_as_bufferfield. These functions will enable access to the instances of the type as input/output buffers.

Next, we look at a few type objects as case studies of how the type object fields are populated.

4.3 Type Object Case Studies

The tuple type

We look at the tuple type to get a feel for how the fields of a type object are populated. We choose this because it is relatively easy to grok given the small size of the implementation - roughly a thousand

plus lines of C including documentation strings. Listing 4.3 shows the implementation of the tuple type.

1 PyTypeObject PyTuple_Type = {

2 PyVarObject_HEAD_INIT(&PyType_Type, 0)

3 "tuple",

4 sizeof(PyTupleObject) - sizeof(PyObject *),

5 sizeof(PyObject *),

6 (destructor)tupledealloc, /* tp_dealloc */

7 0, /* tp_print */

8 0, /* tp_getattr */

9 0, /* tp_setattr */

10 0, /* tp_reserved */

11 (reprfunc)tuplerepr, /* tp_repr */

12 0, /* tp_as_number */

13 &tuple_as_sequence, /* tp_as_sequence */

14 &tuple_as_mapping, /* tp_as_mapping */

15 (hashfunc)tuplehash, /* tp_hash */

16 0, /* tp_call */

17 0, /* tp_str */

18 PyObject_GenericGetAttr, /* tp_getattro */

19 0, /* tp_setattro */

20 0, /* tp_as_buffer */

21 Py_TPFLAGS_DEFAULT | Py_TPFLAGS_HAVE_GC |

22 Py_TPFLAGS_BASETYPE | Py_TPFLAGS_TUPLE_SUBCLASS, /* tp_flags */

23 tuple_doc, /* tp_doc */

24 (traverseproc)tupletraverse, /* tp_traverse */

25 0, /* tp_clear */

26 tuplerichcompare, /* tp_richcompare */

27 0, /* tp_weaklistoffset */

28 tuple_iter, /* tp_iter */

29 0, /* tp_iternext */

30 tuple_methods, /* tp_methods */

31 0, /* tp_members */

32 0, /* tp_getset */

33 0, /* tp_base */

34 0, /* tp_dict */

35 0, /* tp_descr_get */

36 0, /* tp_descr_set */

37 0, /* tp_dictoffset */

38 0, /* tp_init */

39 0, /* tp_alloc */

40 tuple_new, /* tp_new */

41 PyObject_GC_Del, /* tp_free */

42 };

We look at the fields that are populated in this type.

-

PyObject_VAR_HEADhas been initialized with a type object - PyType_Type as the type. Recall that the type of a type object is Type. A look at the PyType_Type type object shows that the type of PyType_Type is itself. -

tp_nameis initialized to the name of the type - tuple. -

tp_basicsizeandtp_itemsizerefer to the size of the tuple object and items contained in the tuple object, and this is filled in accordingly. -

tupledeallocis a memory management function that handles the deallocation of memory when a tuple object is destroyed. -

tuplerepris the function invoked when thereprfunction is called with a tuple instance as an argument. -

tuple_as_sequenceis the set of sequence methods that the tuple implements. Recall that a tuple supportin,lenetc. sequence methods. -

tuple_as_mappingis the set of mapping methods supported by a tuple - in this case, the keys are integer indexes only. -

tuplehashis the function that is invoked whenever the hash of a tuple object is required. This comes into play when tuples are used as dictionary keys or in sets. -

PyObject_GenericGetAttris the generic function invoked when referencing attributes of a tuple object. We look at attribute referencing in subsequent sections. -

tuple_docis the documentation string for a tuple object. -

tupletraverseis the traversal function for garbage collection of a tuple object. This function is used by the garbage collector to help in the detection of reference cycle1. -

tuple_iteris a method that gets invoked when theiterfunction is called on a tuple object. In this case, a completely differenttuple_iteratortype is returned so there is no implementation for thetp_iternextmethod. -

tuple_methodsare the actual methods of a tuple type. -

tuple_newis the function invoked to create new instances of tuple type. -

PyObject_GC_Delis another field that references a memory management function.

The additional fields with 0 values are empty because tuples do not require those functionalities. Take the tp_init field, for example, a tuple is an immutable type, so once created it cannot be changed, so there is no need for any initialization beyond what happens in the function

referenced by tp_new; hence this field is left empty.

The type type

The other type we look at is the type type. This is the metatype for all built-in types and vanilla user-defined types (a user can define a new metatype) - notice how this type is used when initializing the tuple object in PyVarObject_HEAD_INIT. When discussing types, it is essential to distinguish between objects that have type as their type and objects with a user-defined type. This distinction comes very much to the fore when dealing with attribute referencing in objects.

This type defines methods used when working with other types, and the fields are similar to those from the previous section. When creating new types, as we will see in subsequent sections, this type is used.

The object type

Another necessary type is the object type; this is very similar to the type type. The object type

is the root type for all user-defined types and provides some default values that fill in

the type fields of a user-defined type. This is because user-defined types behave differently compared to types that have type as their type. As we will see in subsequent

section, functions such as that for the attribute resolution algorithm provided by the object type differ

significantly from those offered by the type type.

4.4 Minting type instances

With an assumed firm understanding of the rudiments of types, we can progress onto one of the most

fundamental functions of types, which is the creation of new instances.

To fully understand the process of creating new type instances, it is important to remember that just as we differentiate between built-in types and user-defined types 2, the internal structure

of both differs. The tp_new field is the cookie cutter for new type instances in

Python. The

documentation

for the tp_new slot as reproduced below gives a brilliant description of the function that should fill this slot.

An optional pointer to an instance creation function. If this function is NULL for a particular type, that type cannot be called to create new instances; presumably, there is some other way to create instances, like a factory function. The function signature is

PyObject *tp_new(PyTypeObject *subtype, PyObject *args, PyObject *kwds)

The subtype argument is the type of the object being created; the

argsandkwdsarguments are the positional and keyword arguments of the call to the type. Note that subtype doesn’t have to equal the type whose tp_new function is called; it may be a subtype of that type (but not an unrelated type). Thetp_newfunction should callsubtype->tp_alloc(subtype, nitems)to allocate space for the object, and then do only as much further initialization as is absolutely necessary. Initialization that can safely be ignored or repeated should be placed in thetp_inithandler. A good rule of thumb is that for immutable types, all initialization should take place intp_new, while for mutable types, most initialization should be deferred totp_init.

This field is inherited by subtypes but not by static types whose

tp_baseisNULLor&PyBaseObject_Type.

We will use the tuple type from the previous section as an example

of a builtin type. The tp_new field of the tuple type references the - tuple_new method shown in

Listing 4.4, which handles the creation of new tuple objects. A new tuple object is created by dereferencing and then invoking this function.

1 static PyObject * tuple_new(PyTypeObject *type, PyObject *args,

2 PyObject *kwds){

3 PyObject *arg = NULL;

4 static char *kwlist[] = {"sequence", 0};

5

6 if (type != &PyTuple_Type)

7 return tuple_subtype_new(type, args, kwds);

8 if (!PyArg_ParseTupleAndKeywords(args, kwds, "|O:tuple", kwlist, &arg))

9 return NULL;

10

11 if (arg == NULL)

12 return PyTuple_New(0);

13 else

14 return PySequence_Tuple(arg);

15 }

Ignoring the first and second conditions for creating a tuple in Listing 4.4, we follow the third

condition, if (arg==NULL) return PyTuple_New(0) down the rabbit hole to find out how this works.

Overlooking the

optimizations abound in the PyTuple_New function, the segment of the function that creates a new tuple object is the

op = PyObject_GC_NewVar(PyTupleObject, &PyTuple_Type, size) call which allocates memory

for an instance of the PyTuple_Object structure on the heap. This is where a difference between internal

representation of built-in types and user-defined types comes to the fore - instances of built-ins

like tuple are actually C structures. So what does this C struct backing a tuple object look like? It is found in the Include/tupleobject.h as the PyTupleObject typedef, and this is shown in Listing 4.5 for convenience.

1 typedef struct {

2 PyObject_VAR_HEAD

3 PyObject *ob_item[1];

4

5 /* ob_item contains space for 'ob_size' elements.

6 * Items must typically not be NULL, except during construction when

7 * the tuple is not yet visible outside the function that builds it.

8 */

9 } PyTupleObject;

The PyTupleObject is defined as a struct having a PyObject_VAR_HEAD and an array of PyObject

pointers - ob_items. This leads to a very efficient implementation as opposed to representing the instance using Python data structures.

Recall that an object is a collection of methods and data. The PyTupleObject in this case provides

space to hold the actual data that each tuple object contains so we can have multiple instances of

PyTupleObject allocated on the heap but these will all reference the single PyTuple_Type type

that provides the methods that can operate on this data.

Now consider a user-defined class such as in LIsting 4.6.

1 class Test:

2 pass

The Test type, as you would expect, is an object of instance Type. To create an instance of the Test

type, the Test type is called as such - Test(). As always, we can go down the rabbit hole to convince

ourselves of what happens when the type object is called. The Type type has a function reference - type_call that fills the tp_call field, and this is dereferenced whenever the call notation is used on an instance of Type. A snippet of the

type_call

the function implementation is shown in listing 4.7.

1 ...

2 obj = type->tp_new(type, args, kwds);

3 obj = _Py_CheckFunctionResult((PyObject*)type, obj, NULL);

4 if (obj == NULL)

5 return NULL;

6

7 /* Ugly exception: when the call was type(something),

8 don't call tp_init on the result. */

9 if (type == &PyType_Type &&

10 PyTuple_Check(args) && PyTuple_GET_SIZE(args) == 1 &&

11 (kwds == NULL ||

12 (PyDict_Check(kwds) && PyDict_Size(kwds) == 0)))

13 return obj;

14

15 /* If the returned object is not an instance of type,

16 it won't be initialized. */

17 if (!PyType_IsSubtype(Py_TYPE(obj), type))

18 return obj;

19

20 type = Py_TYPE(obj);

21 if (type->tp_init != NULL) {

22 int res = type->tp_init(obj, args, kwds);

23 if (res < 0) {

24 assert(PyErr_Occurred());

25 Py_DECREF(obj);

26 obj = NULL;

27 }

28 else {

29 assert(!PyErr_Occurred());

30 }

31 }

32 return obj;

In Listing 4.7, we see that when a Type object instance is called, the function referenced by the tp_new field is invoked to create a new instance of that type. The tp_init function is also called if it exists to initialize the new instance. This process explains builtin types because, after all, they have their own tp_new and tp_init functions defined already, but what about user-defined types? Most times, a user does not define a __new__ function for a new type (when defined, this will go into the

tp_new field during class creation). The answer to this also lies with the type_new function that fills the tp_new field of the Type.

When creating a user-defined type, such as Test, the type_new function checks for

the presence of base types (supertypes/classes) and when there are none, the PyBaseObject_Type

type is added as a default base type, as shown in listing 4.8.

PyBaseObject_Type is added to list of bases...

if (nbases == 0) {

bases = PyTuple_Pack(1, &PyBaseObject_Type);

if (bases == NULL)

goto error;

nbases = 1;

}

...

This default base type defined in the Objects/typeobject.c module contains some default

values for the various fields. Among these defaults are values for the tp_new and tp_init fields.

These are the values that get called by the interpreter for a user-defined type. In the case where

the user-defined type implements its methods such as __init__, __new__ etc., these values are

called rather than those of the PyBaseObject_Type type.

One may notice that we have not mentioned any object structures like the tuple object structure,

tupleobject, and ask - if no object structures are defined for a user-defined class, how are

object instances handled and where do objects attributes that do not map to slots in the type reside?

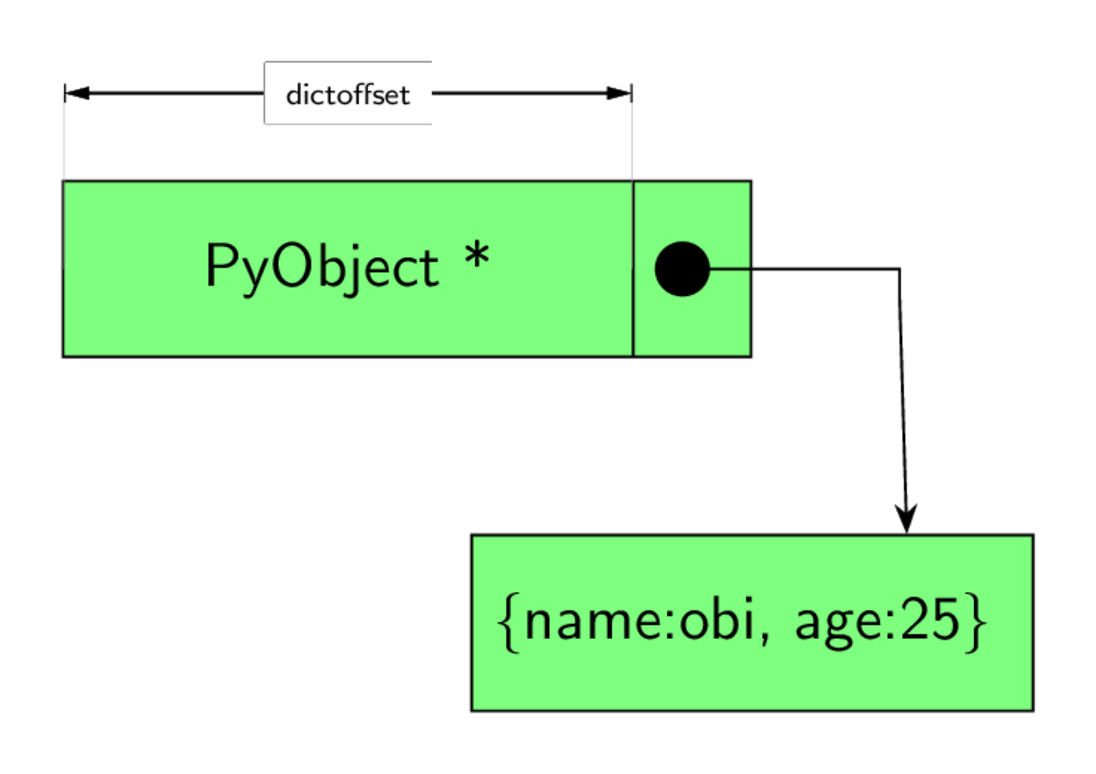

This has to do with the tp_dictoffset field - a numeric field in type object. Instances

are created as PyObjects, however, when this offset value is non-zero in the instance type,

it specifies the offset of the

instance attribute dictionary from the instance (the PyObject) itself as shown in figure 4.0 so for

an instance of a Person type, the attribute dictionary can be assessed by adding this offset value

to the origin of the PyObject memory location.

For example, if an instance PyObject is at 0x10 and the offset is 16 then the instance dictionary

that contains instance attributes is found at 0x10 + 16.

This is not the only way instances store their attributes, as we will see in the following section.

4.5 Objects and their attributes

Types and their attributes (variables and methods) are central to object-oriented programming.

Conventionally, types and instances store their attributes using a dict data structure, but this is not the full story in cases of instances that have the __slots__ attribute defined. This dict data structure resides in one of two places, depending on the type of the object, as was mentioned in the previous section.

- For objects with a type of

Type, thetp_dictslot of type structure is a pointer to adictthat contains values, variables, and methods for that type. In the more conventional sense, we say thetp_dictfield of the type object data structure is a pointer to thetypeorclassdict. - For objects with user-defined types, that

dictdata structure when present is located just after thePyObjectstructure that represents the object. Thetp_dictoffsetvalue of the type of the object gives the offset from the start of an object to this instancedictcontains the instance attributes.

Performing a simple dictionary access to obtain attributes looks simpler than it actually is. Infact,

searching for attributes is way more involved than just checking tp_dict value for instance of

Type or the dict at tp_dictoffset for instances of user-defined types. To get a full understanding, we have to discuss the descriptor protocol - a protocol at the heart of attribute referencing in Python.

The Descriptor HowTo Guide is an excellent

introduction to descriptors, but the following section provides a cursory description of descriptors.

Simply put, a descriptor is an object that implements the

__get__, __set__ or __delete__ special methods of the descriptor protocol. Listing 4.9 is the signature for each of these methods in Python.

descr.__get__(self, obj, type=None) --> value

descr.__set__(self, obj, value) --> None

descr.__delete__(self, obj) --> None

Objects implementing only the __get__ method are non-data descriptors so they can only be read from

after initialization. In contrast, objects implementing the __get__ and __set__ are data descriptors meaning that such descriptor objects are writeable. We are interested in the application of descriptors to object attribute representation. The TypedAttribute descriptor in listing 4.10 is an example of a descriptor used to represent an object attribute.

class TypedAttribute:

def __init__(self, name, type, default=None):

self.name = "_" + name

self.type = type

self.default = default if default else type()

def __get__(self, instance, cls):

return getattr(instance, self.name, self.default)

def __set__(self,instance,value):

if not isinstance(value,self.type):

raise TypeError("Must be a %s" % self.type)

setattr(instance,self.name,value)

def __delete__(self,instance):

raise AttributeError("Can't delete attribute")

The TypedAttribute descriptor class enforces rudimentary type checking for any class’ attribute that it represents. It is important to note that descriptors are useful in this kind of case only when defined at the class level rather than instance-level, i.e., in __init__ method, as shown in listing 4.11.

class Account:

name = TypedAttribute("name",str)

balance = TypedAttribute("balance",int, 42)

def name_balance_str(self):

return str(self.name) + str(self.balance)

>> acct = Account()

>> acct.name = "obi"

>> acct.balance = 1234

>> acct.balance

1234

>> acct.name

obi

# trying to assign a string to number fails

>> acct.balance = '1234'

TypeError: Must be a <type 'int'>

If one thinks carefully about it, it only makes sense for this kind of descriptor to be defined at the type level because if defined at the instance the level, then any assignment to the attribute will overwrite the descriptor.

A review of the Python VM source code shows the importance of descriptors. Descriptors provide the mechanism behind properties,

static methods, class methods, and a host of other functionality in Python. Listing 4.12, the algorithm for resolving an attribute from an instance,b, of a user-defined type, is a concrete illustration of the importance of descriptors.

The algorithm in Listing 4.12 shows that during attribute referencing we first check for descriptor objects;

it also illustrates how the TypedAttribute descriptor can represent an attribute of an

object - whenever an attribute is referenced such as b.name the VM searches the Account

type object for the attribute, and in this case, it finds a TypedAttribute descriptor; the VM then calls __get__ method of the descriptor accordingly. The TypedAttribute example illustrates a descriptor

but is somewhat contrived; to get a real touch of how important descriptors are to the core of the

language, we consider some examples that show how they are applied.

Do note that the attribute reference algorithm in listing 4.12 differs from the algorithm used when referencing an attribute whose type is type. Listing 4.3 shows the algorithm for such.

Examples of Attribute Referencing with Descriptors inside the VM

Consider the type data structure

discussed earlier in this chapter. The tp_descr_get and tp_descr_set fields in a type data structure can be filled in by any type instance to satisfy the descriptor protocol. A function object

is a perfect place to show how this works.

Given the type definition, Account from listing

4.11, consider what happens when we reference the method, name_balance_str, from the class as

such - Account.name_balance_str and when we reference the same method from an instance as shown in listing 4.14.

<bound method Account.name_balance_str of <__main__.Account object at

0x102a0ae10>>

>> Account.name_balance_str

<function Account.name_balance_str at 0x102a2b840>

Looking at the snippet from listing 4.14, although we seem to reference the same attribute, the actual objects returned are different in value and type. When referenced from the account type, the returned value is a function type, but when referenced from an instance of the account type, the result is a bound method type. This is possible because functions are descriptors too. Listing 4.15 is the definition of a function object type.

&PyType_Type, 0)

"function",

sizeof(PyFunctionObject),

0,

(destructor)func_dealloc, /* tp_dealloc */

0, /* tp_print */

0, /* tp_getattr */

0, /* tp_setattr */

0, /* tp_reserved */

(reprfunc)func_repr, /* tp_repr */

0, /* tp_as_number */

0, /* tp_as_sequence */

0, /* tp_as_mapping */

0, /* tp_hash */

function_call, /* tp_call */

0, /* tp_str */

0, /* tp_getattro */

0, /* tp_setattro */

0, /* tp_as_buffer */

Py_TPFLAGS_DEFAULT | Py_TPFLAGS_HAVE_GC,/* tp_flags */

func_doc, /* tp_doc */

(traverseproc)func_traverse, /* tp_traverse */

0, /* tp_clear */

0, /* tp_richcompare */

offsetof(PyFunctionObject, func_weakreflist), /* tp_weaklistoffset */

0, /* tp_iter */

0, /* tp_iternext */

0, /* tp_methods */

func_memberlist, /* tp_members */

func_getsetlist, /* tp_getset */

0, /* tp_base */

0, /* tp_dict */

func_descr_get, /* tp_descr_get */

0, /* tp_descr_set */

offsetof(PyFunctionObject, func_dict), /* tp_dictoffset */

0, /* tp_init */

0, /* tp_alloc */

func_new, /* tp_new */

};

The function object fills in the tp_descr_get field with a func_descr_get function thus instances

of the function type are non-data descriptors.

Listing 4.16 shows the implementation of the funct_descr_get method.

static PyObject * func_descr_get(PyObject *func, PyObject *obj, PyObject *type){

if (obj == Py_None || obj == NULL) {

Py_INCREF(func);

return func;

}

return PyMethod_New(func, obj);

}

The func_descr_get can be invoked during either type attribute resolution or instance attribute resolution, as described in the previous section. When invoked from a type, the call to the func_descr_get

is as such local_get(attribute, (PyObject *)NULL,(PyObject *)type) while when invoked from an attribute

reference of an instance of a user-defined type, the call signature is f(descr, obj, (PyObject *)Py_TYPE(obj)).

Going over the implementation for func_descr_get in listing 4.16, we see that if the instance is NULL, then the function

itself is returned while if an instance is passed in to the call, a new method object is created

using the function and the instance. This sums up how Python can return a different type for the same function reference using a descriptor.

In another instance of the importance of descriptors, consider the snippet in Listing 4.17 which

shows the result of accessing the __dict__ attribute from both an instance of the built-in type

and an instance of a user-defined type.

__dict__ attribute from an instance of the built-in type and an instance of a user-defined typeclass A:

pass

>>> A.__dict__

mappingproxy({'__module__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__weakref__': <attribute '\

__weakref__' of 'A' objects>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'A' objects>})

>>> i = A()

>>> i.__dict__

{}

>>> A.__dict__['name'] = 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'mappingproxy' object does not support item assignment

>>> i.__dict__['name'] = 2

>>> i.__dict__

{'name': 2}

>>>

Observe from listing 4.17 that both objects do not return the vanilla dictionary type when the

__dict__ attribute is referenced. The type object seems to return an immutable mapping proxy that we cannot even assign. In contrast, the instance of type returns a vanilla dictionary mapping that supports all the usual dictionary functions. So it seems that attribute referencing is done differently for these objects. Recall the algorithm described for attribute search from a couple of sections back.

The first step is to search the __dict__ of the type of the object for the attribute, so we go ahead

and do this for both objects in listing 4.18.

__dict__ in type of objects>>> type(type.__dict__['__dict__']) # type of A is type

<class 'getset_descriptor'>

type(A.__dict__['__dict__'])

<class 'getset_descriptor'>

We see that the __dict__ attribute is represented by data descriptors for both objects, and that is why we can get different object types. We would like to find out what happens under the covers for this descriptor, just as we did in the functions and bound methods. A good

place to start is the Objects/typeobject.c module and the definition for the type type

object. An interesting field is the tp_getset field that contains an array of

C structs (PyGetSetDef values) shown in listing 4.19. This is the collection of values that will be represented by descriptors in type's type __dict__ attribute - the __dict__ attribute is the mapping referred to by the tp_dict slot of the type object points.

__dict__ in type of objectsstatic PyGetSetDef type_getsets[] = {

{"__name__", (getter)type_name, (setter)type_set_name, NULL},

{"__qualname__", (getter)type_qualname, (setter)type_set_qualname, NULL},

{"__bases__", (getter)type_get_bases, (setter)type_set_bases, NULL},

{"__module__", (getter)type_module, (setter)type_set_module, NULL},

{"__abstractmethods__", (getter)type_abstractmethods,

(setter)type_set_abstractmethods, NULL},

{"__dict__", (getter)type_dict, NULL, NULL},

{"__doc__", (getter)type_get_doc, (setter)type_set_doc, NULL},

{"__text_signature__", (getter)type_get_text_signature, NULL, NULL},

{0}

};

These values are not the only ones represented by descriptors in the type dict; there are other values such as

the tp_members and tp_methods values which have descriptors created and insert into the tp_dict

during type initialization. The insertion of these values into the dict happens when the PyType_Ready function is called on the type. As part of the PyType_Ready function initialization process, descriptor objects are created

for each entry in the type_getsets and then added into the tp_dict mapping - the add_getset

function in the Objects/typeobject.c handles this.

Returning to our __dict__, attribute, we know that after initialization of the type, the __dict__

attribute exists in the tp_dict field of the type, so let’s see what the getter function of this descriptor does. The getter function is the type_dict function shown in listing 4.20.

typestatic PyObject * type_dict(PyTypeObject *type, void *context){

if (type->tp_dict == NULL) {

Py_INCREF(Py_None);

return Py_None;

}

return PyDictProxy_New(type->tp_dict);

}

The tp_getattro field points to the function that is the first port of call for getting attributes for any object. For the type object, it points to the type_getattro function. This method, in turn,

implements the attribute search algorithm as described in listing 4.13. The

function invoked by the descriptor found in the type dict for the __dict__ attribute is the

type_dict function given in listing 4.20, and it is pretty easy to understand.

The return value is of interest to us here; it is a dictionary proxy to the actual dictionary that

holds the type attribute; this explains the mappingproxy type that is returned when we query the __dict__ attribute of a type object.

So what about the instance of A, a user-defined type, how is the __dict__ attribute resolved? Now

recall that A is an object of type type so we go hunting in the Object/typeobject.c

module to see how new type instances are created. The tp_new slot of the PyType_Type contains the

type_new function that handles the creation of new type objects. Perusing through all the type creation code in the function, one stumbles on the snippet in listing 4.21.

tp_getset field for user defined typeif (type->tp_weaklistoffset && type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_full;

else if (type->tp_weaklistoffset && !type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_weakref_only;

else if (!type->tp_weaklistoffset && type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_dict_only;

else

type->tp_getset = NULL;

Assuming the first conditional is true as the tp_getset field is filled with the value shown in Listing 4.22.

getset values for instance of typestatic PyGetSetDef subtype_getsets_full[] = {

{"__dict__", subtype_dict, subtype_setdict,

PyDoc_STR("dictionary for instance variables (if defined)")},

{"__weakref__", subtype_getweakref, NULL,

PyDoc_STR("list of weak references to the object (if defined)")},

{0}

};

When (*tp->tp_getattro)(v, name) is invoked, the tp_getattro field which contains a pointer to

the PyObject_GenericGetAttr is called. This function is responsible for

implementing the attribute search algorithm for a user-defined types. In the case of the __dict__

attribute, the descriptor is found in the object type’s dict and the __get__ function of the

descriptor is the subtype_dict function defined for the __dict__ attribute from listing 4.21.

The subtype_dict getter function is shown in listing 4.23.

__dict__ attribute of a user-defined typestatic PyObject * subtype_dict(PyObject *obj, void *context){

PyTypeObject *base;

base = get_builtin_base_with_dict(Py_TYPE(obj));

if (base != NULL) {

descrgetfunc func;

PyObject *descr = get_dict_descriptor(base);

if (descr == NULL) {

raise_dict_descr_error(obj);

return NULL;

}

func = Py_TYPE(descr)->tp_descr_get;

if (func == NULL) {

raise_dict_descr_error(obj);

return NULL;

}

return func(descr, obj, (PyObject *)(Py_TYPE(obj)));

}

return PyObject_GenericGetDict(obj, context);

}

The get_builtin_base_with_dict returns a value when the object instance is in an inheritance hierarchy, so ignoring that for this instance is appropriate. The PyObject_GenericGetDict object is

invoked. Listing 4.24 shows the PyObject_GenericGetDict and an associated helper that fetches the instance dict. The actual

get the dict function is the _PyObject_GetDictPtr function that queries the object for its

dictoffset and uses that to compute the address of the instance dict. In a situation where

this function returns a null value, PyObject_GenericGetDict can return a new dict to the calling function.

PyObject * PyObject_GenericGetDict(PyObject *obj, void *context){

PyObject *dict, **dictptr = _PyObject_GetDictPtr(obj);

if (dictptr == NULL) {

PyErr_SetString(PyExc_AttributeError,

"This object has no __dict__");

return NULL;

}

dict = *dictptr;

if (dict == NULL) {

PyTypeObject *tp = Py_TYPE(obj);

if ((tp->tp_flags & Py_TPFLAGS_HEAPTYPE) && CACHED_KEYS(tp)) {

DK_INCREF(CACHED_KEYS(tp));

*dictptr = dict = new_dict_with_shared_keys(CACHED_KEYS(tp));

}

else {

*dictptr = dict = PyDict_New();

}

}

Py_XINCREF(dict);

return dict;

}

PyObject ** _PyObject_GetDictPtr(PyObject *obj){

Py_ssize_t dictoffset;

PyTypeObject *tp = Py_TYPE(obj);

dictoffset = tp->tp_dictoffset;

if (dictoffset == 0)

return NULL;

if (dictoffset < 0) {

Py_ssize_t tsize;

size_t size;

tsize = ((PyVarObject *)obj)->ob_size;

if (tsize < 0)

tsize = -tsize;

size = _PyObject_VAR_SIZE(tp, tsize);

dictoffset += (long)size;

assert(dictoffset > 0);

assert(dictoffset % SIZEOF_VOID_P == 0);

}

return (PyObject **) ((char *)obj + dictoffset);

}

This explanation succinctly sums up how the Python VM uses descriptors to implement type-dependent custom attribute access depending on types. Descriptors are pervasive

in the VM; __slots__, static and class methods, properties are just some further examples of language features that are made possible by the use of descriptors.

4.6 Method Resolution Order (MRO)

We have mentioned MRO when discussing attribute referencing without discussing it much so in this section, we go into a bit more detail on MRO. Types can belong to a multiple inheritance hierarchy, so there is a need for some kind of order defining how to search for methods when a type inherits from multiple classes; this order which is referred to as |Method Resolution Order (MRO) is also actually used when searching for other non-method attributes as we saw in the algorithm for attribute reference resolution. The article, Python 2.3 Method Resolution order, is an excellent and easy to read documentation of the method resolution algorithm used in Python; a summary of the main points are reproduced here.

Python uses the C3 algorithm for building the method resolution order (also referred to as linearization here) when a type inherits from multiple base types. Listing 4.25 shows some notations used in explaining this algorithm.

C1 C2 ... CN denotes the list of classes [C1, C2, C3 .., CN]The head of the list is its first element: head = C1The tail is the rest of the list: tail = C2 ... CN.C + (C1 C2 ... CN) = C C1 C2 ... CN denotes the sum of the lists [C] +

[C1, C2, ... ,CN].Consider a type C in a multiple inheritance hierarchy, with C inheriting from the base types

B1, B2, ... , BN, the linearization of C is the sum of C plus the merge of the linearizations of the parents and the list of the parents - L[C(B1 ... BN)] = C + merge(L[B1] ... L[BN], B1 ... BN).

The linearization of the object type which has no parents is trivial - L[object] = object.

The merge operation is calculated according to the following algorithm:

take the head of the first list, i.e., L[B1][0]; if this head is not in the tail of any of the other lists, then add it to the linearization of C and remove it from the lists in the merge, otherwise look at the head of the next list and take it, if it is a good head. Then repeat the operation until all the classes have been removed, or it is impossible to find good heads. In this case, it is impossible to construct the merge; Python 2.3 will refuse to create the class C and will raise an exception.

Some type hierarchies cannot be linearized using this algorithm, and in such cases, the VM throws an error and does not create such hierarchies.

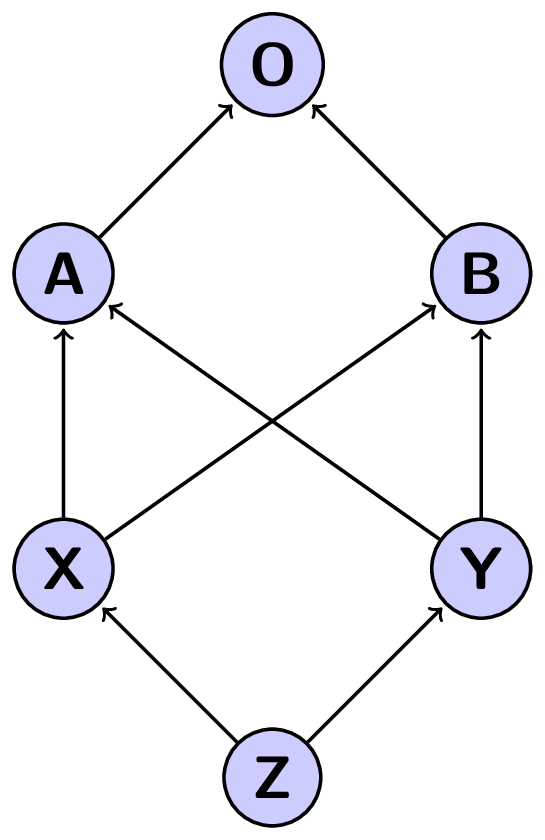

Assuming we have an inheritance hierarchy such as that shown in figure 4.1, the algorithm for creating

the MRO would proceed as follows starting from the top of the hierarchy with O, A, and B.

The linearizations of O, A and B are trivial:

O, A and B from figure 4.1The linearization of X can be computed as L[X] = X + merge(AO, BO, AB)

A is a good head, so it is added to the linearization, and we are left to compute merge(O, BO, B).

O is not a good head because it is in the tail of BO, so we move to the next sequence. B is a good

head, so we add it to the linearization, and we are left to compute merge(O, O), which evaluates to O.

The resulting linearization of X - L[X] = X A B O.

Like the procedure from above, the linearization for Y is computed, as shown in Listing 4.27:

Y from figure 4.1With linearizations for X and Y computed, we can compute that for Z as shown in listing 4.28.

Z from figure 4.1