Table of Contents

Preface

So you’re a business analyst that dropped into the task to document some large system. Likely in the order to have a base for improving the existing systems. And probably some legacy systems need documentation at all. You’re looking for Ariadne’s thread to effectively solve your task? Here it is!

This book will give a recipe how to document heterogenous environments with UML. I am using the tool Enterprise Architect for my examples. The method shown is not specifically bound to that tool. However, I still recommend it as the best tool on the market1.

This book starts with a short intro to UML for business analysts and one about heterogenous systems in general. As basic knowledge of UML is a prerequisite, but can’t taken as granted for all readers, the next chapter gives a short intro into UML. The focus of this book is to enable business analysts to basically document their systems using UML (with Enterprise Architect). So we step from hardware to software and via use cases to requirements. In the end you should have a complete documentation of your system landscape. Each chapter is constructed as tutorial which takes you by the hand and leads you to a complete architecture model step by step. It is up to you how deep you dive into the documentation of the single system parts.

The examples and tutorials were build with the EA version current at the time of writing this book, which is V10. Most of it can also be performed with earlier versions of EA. Where I remembered it, the difference to those earlier versions is explained with footnotes. If you eventually find something where your version behaves even different: send me a mail. Purchasers of this book will get updates in case Sparx will change menu positions once again, or correct bugs which currently prevent/obstruct the use of a few features.

- Once I called it the one-eyed amongst the blind. But that’s a different story.↩

Copyright and Disclaimer

Also all of the information in this book has been tested by me in many circumstances I can not hold any liability for use of the here presented information1. However, I’d be glad to receive any kind of feedback2 to correct future updates of this book which you will receive for free in turn. Having said this, all information presented here is subject to change without notice.

The names of actual companies and products mentioned herein may be the trademarks of their respective owners.

- I really loathe writing such legal blurb since it should be obvious. By the way: German law applies! (Does that change anything?)↩

- Just send me a mail to thomas.kilian@me.com.↩

I Introduction

In this Part you will find some general instructions about usage of UML and Enterprise Architect.

1. Landmarks

This chapter deals with the analysis domain itself. It will give a glance at the spoken language UML, the IT landscape and tool Enterprise Architect to bring things together.

The thread you will find in this book is likely not the only one you need. You might leave the path for good reasons. If any of the areas are new to you, don’t walk away too far. You might get lost. It is a good idea to have a cutting through the whole area before doing so.

1.1 UML

The acronym UML stands for Unified Modeling Language. It is an open standard, defined and published by the Object Management Group. A few facts:

- UML is a language like e.g. Chinese

- but much easier to learn.

- The number of symbols is mainly reduced to

- ovals (use cases),

- rectangles (things),

- lines (relations between things)

- and a few other seldom used icons1.

- UML can be used for almost anything in the information technology.

UML may well be used to express things outside the IT. Like in any language you can express things

- elegantly,

- colloquially and

- vulgarly.

The rate of understandability must not necessarily be proportional. UML is all about communication – transporting ideas from one person to another. As a rule of thumb the following applies:

- A good text is

- hard to create,

- will be understood by many people and is therefore

- helpful.

- A bad text

- will be understood by few people and is therefore

- rather useless.

If you want to walk in UML-land it is convenient to speak the language. If you just want to order a lunch you likely do not need to speak the language fluently. Nor must you know all the vocabulary. But the often you visit that land, the more you want to know. By and by you learn the language. Simply by practicing it. So your start will be easy as you have to learn only a few symbols for the beginning.

In order to read UML you have to learn two technologies. First you will find a name and a prose description of model elements. This will tell the reader roughly what the element is all about. Everything (especially in UML) is looked at from a certain perspective. This gives the context where the elements have meaning. If the name is chosen good, it will tell more than half of its story. The prose description will aid in this process of understanding that thing. The second important technology is that of diagrams. You might already have seen complex UML diagrams – probably pinned up the wall by nerds which do not understand their contents either. But the poster looks impressive. That’s like trying to read a text from Shakespeare where your vocabulary is only enough to read the menu of a restaurant. The beauty of such complex poetry/UML can only be enjoyed by people speaking the language fluently. Like for natural languages it’s good to talk UML with a natural speaker. The more you practice, the faster you will learn.

The examples in this book are designed in a way that will help you learn UML the right way: just the parts you need. No Shakespeare. If you’re already a poet yourself you may simply skip that section.

1.2 Heterogenous IT Landscapes

In most business areas you will find a variety of hard- and software resources which all play a part in the orchestra. If the symphony shall sound nicely and enjoying it is important that you know where and why which instrument comes into play. A major target of your documentation must be to identify system components and interfaces, why they exist, which risks are connected and how to optimize the components and their interfaces.

At the high end you will find mainframes. They are used in banking, sales and reservation systems. Their main purpose is to treat so-called transactions at very high volumes. A transaction is a business message that results in a number of operations. A transaction is atomic which means that it either succeeds and all operations are performed or it fails and no side effect has taken place. Usually those mainframes have dedicated hardware for things which “usual” machines perform via software. As a business analyst you must not know about all these details, but if your documentation shows the interfaces this is a very valuable information. And using UML it’s a breeze documenting all this hardware.

Documenting the software for these mainframes is a more challenging task. Only in outlying districts object orientation (and thus easy appliance of UML) is being used. E.g. in the military area where Ada is applied. But most of the software is COBOL, a bit FORTRAN and still quite a number of Assembler. All of that not OO. Neither in design nor in implementation. However, UML is a language for (mostly) technical purposes. And thus it is able to describe also non-OO software. When we go into detail later, you will see that there is quite a large amount of mainframe software you can also describe OO-based.

Since mainframe terminology is not that common any more I will emphasize some of the terms coming from that world. If you don’t need it in your current project then just stow it away for a later one.

Databases on mainframes would be a chapter on their own. So this book will only tangent them. You might need to dive into that matter separately as you need to document data-warehousing.

In the mid-area you will find mainly UNIX and Windows servers. Most of them are used for web front-ends. From UML perspective those are “good old friends” if you look into software. Hardware is by far more simple compared to mainframe so you will be able to do that en passant. Similarly this applies to end-user devices like desktops and laptops.

Besides the usual peripherals such as printers, scanners or plotters you might eventually find dedicated hardware. Again, you would only need to document the interfaces here. Detailed design would likely require special skill and languages like SysML.

Finally there is the important part of networking. You will need to find ways to describe how the network looks like, who is involved in terms of being a provider, what data volumes travel and which system is affected by the network.

The whole documentation needs to provide static aspects which show how components are deployed. This will be the frame for the dynamic view. There are usually a couple of views you need to document for the different stakeholders involved. The good thing is that UML supports creation of such views without much hassle. Though it might be a bit tricky to organize them in a way to handle them elegantly.

1.3 Enterprise Architect

Probably you bought this book because you have decided to use Enterprise Architect in favor of some other tool. First: I recommend this tool as the best choice amongst all competitors. And if you pound in the price, it is really unbeatable. I’m not going to argue pro and con, but be warned that EA has some peculiarities we users do not really deserve. EA comes with almost all bells and whistles one could wish to have for an UML tool. But then it got so fat in the last years that a number of bugs do not get fixed in favor of some other (well, I’d say useless) features. This is my personal impression – your milage may vary. However, you are invited to join the discussion on their (old-fashioned but very lively) discussion forum.

- You will learn a few more elements than the ones mentioned here in the course of working through the tutorials in this book, once you are familiar with the basic concepts.↩

2. A Short Introduction Into UML

As already mentioned UML uses a number of symbols. The whole language is by far more complex than shown here in these few chapters. Luckily you do not need to learn it in full depth. It is enough to focus on a small selection for a start.

You must not learn the following to know it by heart. Instead you might go back to here in the following text whenever you see one of the here described elements.

2.1 Class

We start with the most famous UML element: a Class. It is something you use in your day-to-day language without even thinking about it. If you say Tree you actually mean the class of trees, be it conifer or broadleaf tree. The same goes for Dog, House, Car, etc. You have implicit pictures of these Classes in your mind. And you can create new Classes by finding similarities between things. So you could build a Class of blue pictures, wooden chairs, food, whatever.

Common to all Classes is that you have a couple of shared Attributes. For the blue pictures you would have the shade of blue as Attribute rather than the color. Further you might have the material (linen, wood, etc.) and the artist as Attributes.

Classes can have Methods. This concept is a bit harder to understand. Especially if you come from a classical programming approach. The Methods shown with a Class are some piece of code which deal with that Class. In object oriented programming you have language constructs that allow to bundle Attributes and Methods in Classes. Classical programming languages do not have that out of the box. But with some discipline you can create objects even with COBOL1. The principle is to use COBOL COPYs for the Attributes and have the procedures (Class Methods) bundled and not sparse over many places.

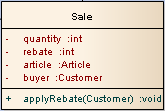

A sample Class might look like this:

Classes are (usually) depicted as rectangles. The top compartment shows the name. Sometimes it also contains a stereotype enclosed in guillemets (like ≪device≫). This is used to show that certain Classes have similarities (Class of Classes). Often you will find two further compartments showing Attributes and Methods.

Class names are always substantives. As per convention the Class name is written in camel case. That means that the first character is capital and any further substantive it is build of will start with a capital and no space (e.g. CustomerOrder). Attributes and Methods are also written in camel case, but they start with a lower case character (like applyRebate in above picture). However, if you have reasons you can deviate from that convention as long as you document that with your model.

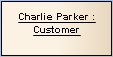

2.2 Object

Once you understand a Class, an Object is easy. It is a concrete thing formed from a Class. Or vice versa: a Class is the abstraction of an Object. E.g. Dog, House and Car are Classes – abstract things. But “Bandit”2, “My house in A-Street” and “Peter’s Porsche” are concrete Objects.

… omitted …

- When I had my software engineering class with Prof. Floyd in the early 80’s she said: “We will use COBOL to demonstrate the concept of object orientation because it is one of the most difficult approaches. If you understand that, you will never forget it.” She was absolutely right.↩

- Probably Rexx would fit better as name for your dog?↩

3. Efficient Use of Enterprise Architect

You should take a little time to get familiar with the basics of Enterprise Architect (EA). In this chapter I will show some of its concepts and useful hints how to actually work with EA. It will probably not replace a professional training. But if you are in a hurry yet or simply need some good advice, you should continue reading. Nevertheless, the following examples are all hands-on and describe exactly what you have to do to get the desired results in Enterprise Architect.

3.1 General

Enterprise Architect is the Swiss Army Knife for the UML modeler. First hand it is an UML modeling and communication tool. It differs in the first respect from tools like Visio which are primarily for drawing pictures. The second aspect is – what I think – the main purpose of this tool. It shall allow you to transport your thoughts to other people and vice versa understand the thoughts of others. That’s what is called communication. Further you can use Enterprise Architect for project documentation, requirements management, project management and a couple of integrative solutions. The major drawback is EA’s user interface, which is not likely to win a design award. You get used to it, but sometimes it simply hurts.

EA holds all model information in a relational database. In its simplest form these are files with EAP extension which are nothing else but Microsoft Access databases. For small modeler groups it might be sufficient to work shared on such a database. But for medium and larger teams you should move to a real RDBMS. The chapter Configuration Management elaborates this aspect.

Each model element, Diagram, Relation, Package (and more) is identified with a so-called GUID which makes it unique all over the universe – at least it’s unlikely to find two different things with the same GUID. Via this identifier it is possible to interchange the contents of single Packages via XMI. Such an XMI can be imported in another tool (or another EA instance), manipulated and imported back so you can see the changes. As simple as that sounds as difficult is reality since relations will eventually turn the whole story into blood, sweat and tears. More about that in the chapter Configuration Management. For now you might keep in mind that you can export a single package, edit this offline and get your work back to the main repository – as long as your changes are local to the package!

3.2 Basic Configuration

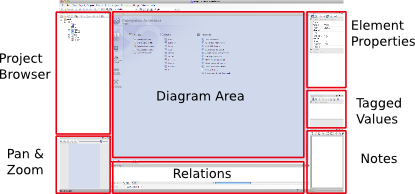

You open EAP files simply by a double-click on an EAP file or via File/Open Project from inside EA. Further when you start EA it offers a list of recently opened projects. Once a project is opened or a blank one has been created you should make yourself familiar with the GUI. You can re-arrange all the docked windows by dragging them to other docked or floating positions. As an EA-power-user-to-be you should configure the layout for a single screen (your laptop) and a second screen (when it’s docked). Here is how it goes: Click-and-drag the title bar of one of the windows (or a single tab if it is part of a tabbed window) and see that it becomes floating. While hovering the floating window watch out for the following icons to appear:

If you drop the floating window over the left one it will be docked at the very left of the main window. Dropping it over one of the compass positions of the cross-formed icon it will dock to that position of the window where the icon is centered. Dropping it in the middle the floating window will add as tab to the specific window. It takes a bit practice to get familiar with that technique but it pays out. It is also possible to make windows auto-hide when they are attached to one of the main window borders. Just click the little pin-icon right in the header bar (see also the Auto-hide in the project browser screenshot below).

My default layout for one screen is this:

Some of these windows are opened with the installation default of EA. Others might need opening from the View menu. For a two-screen configuration use the large screen for the Diagram Area and dock the other windows to one block on the other screen.

… omitted …

II Reverse Engineering

In this part you will learn how to reverse engineer and document heterogenous systems. Starting from hardware via software and use cases the journey will end with requirements.

Most UML guides will show how to construct a system starting from requirements through use cases and system design to a deployed system. Since a business analyst will often face the situation where a system is already present and needs some reverse documentation this book is taking the opposite direction. Of course you can go both ways once you reached the end of this book and design a system from root to leaf.

4. Hardware

A common job to be done first place is to describe the overall hardware architecture. There are two levels you need to keep in mind. The first level is that which is relevant for an overview, where you want to show which of the many mainframes, UNIX (web-) servers and terminals communicate to each other. The second level is the one you need for environment planing. It contains details about the single machine and how these are influenced by/are influencing the environment. But let’s start with a practical example.

4.1 Computer Resources

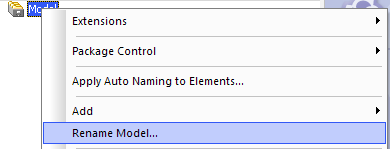

Let us assume that we want to document a commercial system. To do so, create an empty EA repository on your local machine. For the very beginning we do not think of configuration management1 and assume you are a lone worker to document all that stuff. Once you have created the repository, rename the root node

so it resembles the company, system or project name. In this example it will be “Some Commercial System”. Now create a View underneath that root node by clicking the Package icon in the project browser (see picture Project Browser above) and name it “Resources”. The reason for doing this and the next few steps will be explained later. For now just follow them.

Next create a Package inside the View (again click the Package icon with focus on the View) and call it “Computers”.

You will notice that this time you are asked to create a new Diagram. The name of the Diagram is predefined by using the Package name, in this case “Computers”. For the type of Diagram select UML Structural/Deployment. The Diagram is not opened automatically, but it’s already in focus. Just hit enter or double-click it so the blank Diagram will open.

… omitted …

- Do not allow to get confused by CM aspects at this very moment. The ideal solution would be to have everything ready with the right concepts. But that is Utopia. For now it would be ideal if you can sit together with some UML expert, starting to model some concrete things.↩

5. Software

Things get more difficult once you have to deal with software. As already mention I’ll put a little emphasis on the mainframe part since that is even more difficult. You will likely not need to document existent mainframe software in detail as it is generally over-documented. But it often misses the context and this is where the focus should be set: seeing how the system work together and which inter-dependencies they have. Often these minimal views work as eye-opener for many stakeholders.

Since software is quite more complex than hardware (at least from an IT user’s perspective) we start here with the most prominent parts of it: operating systems. From there we will dive into middleware and application systems. More details follow in the next section.

5.1 Operating Systems

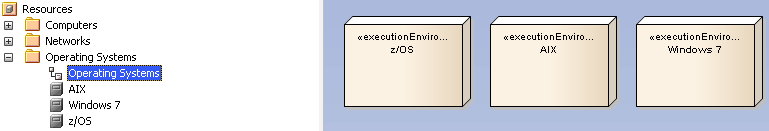

We will use a similar approach as for the hardware. Create a Package Operating Systems in the “Resources” Package, again with a Deployment Diagram. Now add three Execution Environments, namely “z/OS”, “AIX” and “Windows 7”. It should look like this:

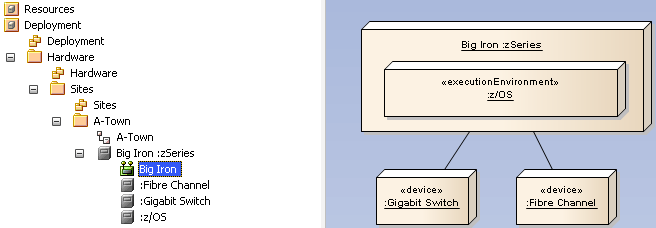

These are the operating systems being utilized in our sample environment. Again, these are classes and not real instances of any deployed OS. These we define right away. Open the composite Diagram for “Big Iron” and Ctrl-drag the “z/OS” onto it. Make it a bit larger and fit into the machine node. When you look at the Diagram you should see the following:

Similarly you should repeat the last steps for “Deep Blue”. For the “Web Service” Ctrl-drag the “AIX” as instance of the operating system onto its composite Diagram. With the same scheme you can supply the notebooks with their Windows OS. If applicable you can also supply routers and switches with the OS they deploy. It depends on your concrete domain to which level you need to document hard- and software.

Where it comes to mass-devices like laptops you often want to show quantities. To do so open the context menu of the according Object and select Advanced/Multiplicity. The following dialog allows to enter a number or free text which then appears in the top right corner of the element in the diagram.

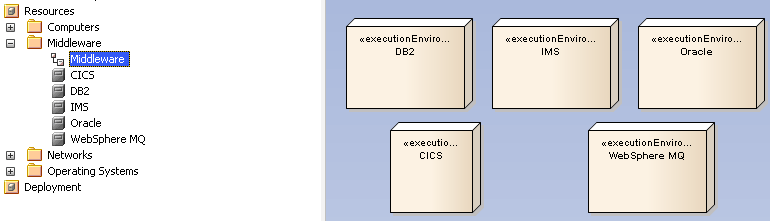

5.2 Middleware

The next level is that between operating systems and applications systems: databases and transaction monitors. Again the scheme is the same as for operating systems. Create three execution environments “DB2”, “IMS” and “Oracle” in the “Middleware” Package which itself is located in the “Resources” Package. Further a “CICS” and a “WebSphere MQ”. That will do for our example.

… omitted …

6. Interfaces

The next step will bring us to Interfaces. Usually these are well (over-) documented and fill a couple of shelfs. It is not necessary to duplicate this information. Instead we make use of them in a condensed format.

Before we get there it is necessary to introduce an UML concept not mentioned before: Ports. They simply mean what the name says. A Port shows some exposed functionality of an element. It is depicted as a small rectangle lying over the border of an element. We make use of such a Port to show how information is transported from/to an application (protocols: SNA, file transfer, HTTP, etc.) and what information is involved (Interface).

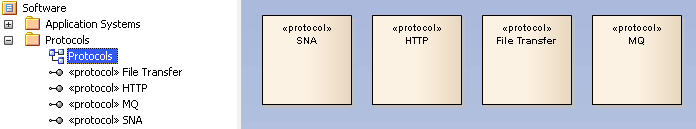

Let us start with creating a new Package “Protocols” in the “Software” View and populate it with some common protocols. Here you must create a Class Diagram in order to be able to access the right elements. These are Interfaces from the toolbox which are named accordingly. Further you have to change the stereotype to ≪protocol≫ manually. The first time you need to type “protocol” in the Stereotype attribute field. Later you should select that value from the drop down (simply to avoid typos here). Finally it should look like this:

Now we can go ahead and make use of these protocol definitions. We start with the “Business Management” application. Here we will define two Ports. One for a “File Transfer” (e.g. to transfer tax information) and another one with “SNA” that is used for communication with “CICS”.

… omitted …

7. Use Cases

This and the following chapter deal with the behavior of the system: first from a user’s view, then from a technical.

You can not understand your system without knowledge of the single Use Cases. They are the reason why all the IT infrastructure was build. Currently you are looking at the system the way: “our system is doing things because some users triggered that behavior”. Your view is IT-centric. By turning the order of the sentence we get: “some users demand a certain functionality which our system must deliver”. That turns the perspective to the users, the group which finally is paying for all these services from which they get some value in return. It is quite difficult to make that turn.

To start with Use Cases create a new View called “User Perspective”.

7.1 Actors

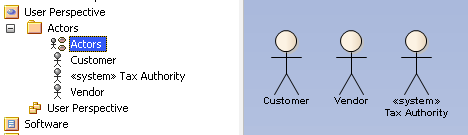

Inside the View create a Package “Actors” containing a Use Case Diagram. Here we add just a few Actors assuming these have been identified in long workshops1: “Customer”, “Tax Authority” and “Vendor”.

The above shown are created from the Actor element out of the tool box. The “Tax Authority” has an additional ≪system≫ stereotype. As mentioned before some people have problems seeing a stick man as a system. You can either choose Advanced/Use Rectangular Notation from the context menu of “Tax Authority”. In that case you must do that for all single occurrences of that actor in any Diagram. Or you create a Class stereotyped ≪system actor≫ which will always appear as rectangle. To create a class in a Use Case Diagram you must choose Other/Class/Class from the toolbox.

Each Actor must have a unique name. It is normally that of a distinct group – eventually a group with just one person or system. It is also very important to describe the Actor in the Notes field. This description should mention the main Use Cases where the Actor is involved. Also its expectations to the system should be described.

If you have identified a larger number of Actors it is a good idea to group them using a boundary which e.g. is named according to the business area. Probably you will also find hierarchical groups of Actors. In that case draw a Generalization from the specialized to the general Actor. E.g. you could have “District Vendors” and “EMEA Vendors” which are specializations of “Vendor”. Those actors perform the same Use Cases as “Vendor” but eventually have some special Use Cases just performed by them.

7.2 Use Cases

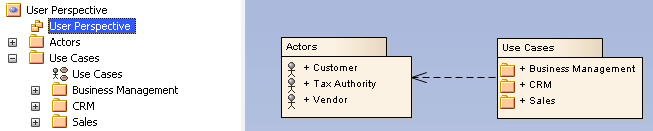

Firstly we have to create another Package inside “User Perspective” which is called “Use Cases”. There will definitely be a number of sub-structures for different business domains in your real case. Just create that structure ahead and place the single Use Cases inside the ‘owning’ domain. You might end up with around a hundred different Use Cases, but you can’t predict that. It strongly depends on the system size and the type of business.

Each of the Packages should contain a Use Case Diagram. The higher level Packages should also contain either Package or Use Case Diagrams to enable model navigability.

The “User Perspective” shows that “Use Cases” depend on the “Actors”. Just a simple dashed arrow; but an important statement!

… omitted …

- It may sound silly, but identifying

Actors is to a high degree non-trivial. Usually you will find moreActors during aUse Casesynthesis.↩

8. Behavior

After having stepped aside from the pure technical view in the last chapter we now come back to technics once again. However, I will not dive very deep into this matter as it is very development-centric and also much too complex to be covered here. Nevertheless the basic techniques can well be learned and will help you a lot in documenting your system.

As we now have a business view on the system it is possible to start a ‘forward re-engineering’. That means we focus on an already known Use Case and try to figure out what happens in the system. During this process you will likely detect design flaws in the system which should be tackled in a further step. The model is excellent to document these flaws so architects and developers can step in later.

8.1 Collaboration

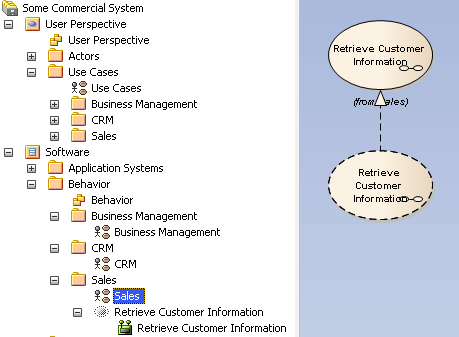

In UML-talk a Collaboration is equal to the Realization of a Use Case showing the behavior of the designed system. And that is exactly what we are going to do.

First we have to create a new Package called “Behavior” inside “Software”. This Package should have the same sub-structure as “User Perspective.Use Cases”. Inside the “Sales” Package create a Collaboration “Retrieve Customer Information”, make it composite, Ctrl-drag the Use Case with the same name onto it and draw a Realization from the Collaboration to the Use Case.

… omitted …

9. Requirements

We have almost reached the ground – or the top. Depending on the way you are looking at the system. When you have added the Requirements, your system documentation will be complete. I can not describe the whole requirements process here but rather try to line out just the basic facts which then must be adopted individually.

Cross-the-board there are two states for Requirements: not documented and over-documented. Only in few cases you have a good Requirements basis. I will try to show a way to reflect them in EA. But however the documentation state is: without Requirements you can not design or document a system.

9.1 Requirements Structure

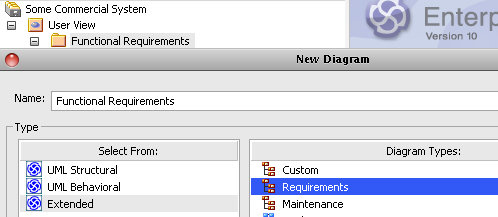

First create a Package that will hold the functional Requirements:

Make sure that you have checked Settings/MDG/Core Extensions1. This will allow you to create an Extended/Requirements Diagram. The name of the Package indicates that it will hold only the functional ones. Below this Package you will usually need a Package structure that reflects the user view of the system. A good approach is to break down functional Requirements according the S.M.A.R.T. paradigm. Google is your friend. There are plenty of articles about that out there.

Another Package in parallel is that for non-functional Requirements. What goes into that are a couple of top-level Packages which heavily depend on the system type. To give some examples:

- Accessibility

- Availability

- Backup

- Compliance

- Documentation

- Disaster recovery

- Legal and licensing issues or patent-infringement-avoidability

- Interoperability

- Maintainability

- Performance / response time (performance engineering)

- Platform compatibility

- Reliability (e.g. mean time between failures - MTBF)

- Reporting

- Resilience

- Response time

- Robustness

- Scalability (horizontal, vertical)

- Security

- Testability

These are just a couple of possible Packages. You might need more or less of them, but at least some. The difference between a functional and a non-functional is that the latter is not directly testable but needs to be judged by a person trained for that specific area (e.g. a lawyer for legal Requirements). In many cases these non-functional Requirements are by numbers less than functional Requirements. But as verifying them is so much harder their implication on the system is much heavier in time and cost.

… omitted …

- Not needed with versions prior to V9.3.↩

III The Second Project

In this part you will learn some more advanced techniques. It is called “Second Project” because you should takle these techniques once you have mastered your first project(s) and you are making your steps towards being a architect rather than an analyst.

10. Working with Stakeholders

Of course you can do a lot of work in your secret chamber to produce a nice model. But it’s not worth a penny if your stakeholder do not understand and/or accept it. I already mentioned what communication between modelers means for a model. Even more important is the communication with stakeholders. There are a couple of ways to establish a good communication with them.

10.1 Teach Stakeholders to Read

The ability to read will bring you definite advantages. And reading the same language without translation is the best way to communicate. Surely it depends on the willingness of people to learn the language. If that is the case then go this way and teach your stakeholders to read UML models in general - and your models in particular.

You probably can tell how talented any of your stakeholders is. Depending on that you may give them read and eventually write access to your central repository or provide them with an appropriate copy of the repository. If granted the write access they can directly add notes to elements in diagrams. It would even be possible to let them correct parts of the model. But it’s rather unlikely that you will find such persons as being a stakeholder in general also means you are conservative. So the best you can expect is to find annotations in the form of notes.

Structure is a key element here. Especially stakeholders need easy entry points where they can find stuff which is relevant for them. When you initially create the repository structure you should keep in mind that different stakeholder will see different views of the model. If you can not layout the package structure accordingly there should be some kind of diagram structure. A possible way to go is to use View/Model Views where you can collect a number of relevant diagrams. This can be done per user. (Of course not only stakeholder can use this feature.)

… omitted …

11. Configuration Management

As a business analyst you should usually not need to care about configuration management. This is a SEP (somebody else’s problem). However, it’s often good to known what happens behind the scenes. Or you were simply put into the task to configure EA since you anyway work with the tool. As mentioned earlier the tutorials in this book were designed to help yourself and to work stand-alone. But it is very unlikely, though not impossible, to have a project in a complex system environment where you will work as lone analyst.

Generally speaking the configuration management has the task to enable a number of people to concurrently work on the same goal with a set of tools. Ideally those tools support the communication with team members1. Again, the real situation can vary in so many parameters that you can not really give a rule of thumb how to setup an individual environment. Therefore I will concentrate on two common settings: a group of analysts working on-site and a number of different groups working at different sites. The best way would be to create a meta-model to document the needs for configuration management.

… omitted …

- It sounds a bit like a tautology. But often you find a configuration which merely hinders communication rather than supporting it.↩

12. The Meta Model

Many people are afraid of UML. Even worse with a meta model. It is like pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps.

You will likely be able to build a meta model only if you are quite firm with UML. However, even if you will not work out a complete meta model (which is good for designing individual profiles, describing the goals of the overall systems and why it is documented), it is a good idea to place a mini-meta-model in front of your system description1. This will show how the model is organized, which modeling rules were applied, etc.

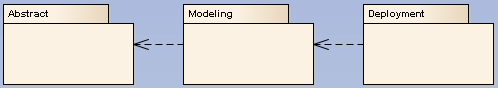

For simplicity sake we will just create a view on the very top called Meta Model or to make your model readers a bit more curious 30.000 ft View2. At this level you should create three different packages

-

Abstract, -

Modelingand Deployment

depending on each other:

The Abstract folder will contain information about the project goals – why we are doing all that fancy modeling stuff. It might be obvious for you, but quite a number of people will not directly understand the usefulness of a model. It should also contain a description of the (paper) deliverables, the stakeholders and their goals as well as any methodology you want to use (e.g. Unified Process, V-Model, Waterfall, Agile, etc.).

The Modeling package describes the rules that shall be applied for the target model. These can be described with simple Requirement elements. Further the package shall contain use case descriptions how to apply the modeling rules. This comes handy when you introduce new team members as they will find here how to do their job formally correct.

The last package Deployment will describe the ‘real’ stuff. While in the previous package you just describe what you use, this package describes the how. Your configuration manager will be happy if you describes this together with him!

… omitted …

- Personally, I prefer a separate repository for the meta-model. The things described therein have a live of their own and should be handled separately. However, you might start with the mine-meta-model inside the main repository and migrate that later when appropriate.↩

- 30.000 ft (approx. 10 km) is the height at which passenger planes usually fly. You get a good perspective of almost everything at that height.↩

Glossary

- Activity Diagram

- A →

Diagramshowing the single steps of a →Use Casescenario. - Actor

- An

Actoris a person or system which interacts with a system in an →Use Case. See also here. - Action

- An

Actionis a single step performed in the execution of an →Use Case. see here - Attribute

- An

Attributeis an UML element which describes an aspect of aClass. See also here. - Architecture

- A logical structure which describes a system such that from requirements over design to deployment each aspect is covered. Each reader (system users, software engineers, requirements mangers, etc.) of an architecture shall be able to easily extract the part that is relevant for him.

- Business Object

- An →

Objectthat is specifically targeted to some sort of business. A good example is a CustomerBusiness Object. - CICS

- Acronym of Customer Information Control System. Used to control the sequence of → transactions on a → mainframe.

- Class

- A

Classis an UML that represents an abstraction of real-world things that are related to each other. AClassis build from a classification process. AClassusually has different →Attributes and →Operations. See also here. - Collaboration

- In UML it is a means to show how a use case is realized in technical terms. A

Collaborationshows the behavior of the system in various facets. - Composite (Diagram)

- Most UML elements can be made composite. In that case they contain a composite or context

Diagramwhich focuses on details of the according element. - Connector

- A visible →

Relationbetween two elements. - Context (Diagram)

- A synonym for a →

Composite Diagram. - Diagram

- A visual presentation of part of an UML model. It helps the model reader to understand a certain aspect of the model.

- Diagram Toolbox

- A context menu for an UML diagram. It contains a relevant subset of UML elements for the individual diagram.

- EA

- Acronym of → Enterprise Architect.

- Enterprise Architect

- Acronym EA. A tool that supports modeling of UML. Developed by Sparx Systems, Australia.

- Folder

- Is another word for →

Package. - GUID

- Acronym for Global Unique IDentifier. A string with hex-chars and dashes which is created in a way such that it is very, very unlikely (but not impossible) to see the same GUID for different elements.

- Instance

- Is another word for →

Object. - IP

- Acronym for Internet Protocol. A protocol which is used to communicate with distributed computers over the

Internet. - Internet

- A network of computers talking to each other via →

IP. - Lifeline

- A dashed line showing (a part of) the life of an object in a

Sequence Diagram. The top of the line shows theObjectname. Elongated rectangles overlaying the dashed line show activity times. The time vector goes from top to bottom. - Mainframe

- A really huge piece of IT hardware, optimized for maximum transaction throughput and resilience.

- Message

- Also

Object Messageis a piece of information sent from one →Objectto another. Besides data it includes an instruction to the receivingObjectwhat kind of action to perform. - Method

- A piece of code performing some action. In a →

ClasstheMethodusually performs the operation on →Attributes of theClass. AMethodcan have parameters and a return value. - MQ

- Message Queue. An IBM product which allows data exchange on a message basis between different platforms including mainframes.

- Object

- An

Objectis a placeholder for a real-world thing.Objects are instantiated from →Classes. Vice versa aClassis an abstraction ofObjects. See also here. - Object Oriented

- A paradigm that sees the world as →

Objectsabstracted by →Classes with →Attributes and →Methods communicating via →Messages. - OO

- →

Objectoriented. - Operation

- A synonym for →

Method. - Package

- A

Packageis an element to structure UML models. … see here - Project Browser

- An EA window which shows the elements of a repository in a tree structure.

- Port

- A means to show exposed behavior of an UML element.

- Quick Linker

- A tool to connect elements in → EA. Selected elements show a little arrow top right which can be dragged to another element or onto a blank space of a →

Diagramin order to create a new element along with a →Connector. - RDBMS

- Acronym for Relational Database Management System. These systems allow to store and retrieve data fast and on high volumes. Single records can be related to each other via keys.

- Relation

- An UML concept to tie two elements together. This is expressed through specific →

Connectors. - RM

- Acronym for Requirements Management.

- Sequence Diagram

- A →

Diagramshowing →Messageexchange between →Objectsrepresented by →Lifelines. - Service Oriented Architecture

- An →

Architecturewhich is focused no services provided over IP. A service corresponds more or less to a →Transactionor a →Methodprovided by a →Class. The services are described via →WSDL. - Shakespeare

- A medieval poet famous for his art to play with words.

- Stereotype

- A grouping characteristic which in → UML is shown as a string enclosed in guillemets (e.g. ≪

device≫). - Tagged Value

- A means to augment UML elements with extra information. Tagged values come in key/value pairs. In → EA the value can be a string, a drop down value or a references to another element.

- Transaction

- Usually an atomic piece of computation performed on business data.

- Use Case

- A

Use Caseis a sequence ofActionstriggered by anActorand return some measurable value to thatActor. See also here. - View

- A

Viewin EA is a special form of a →Package. - WSDL

- Acronym for Web Services Description Language. DescriptionWeb Services Description Language WSDL 1.1 document.

- UML

- An acronym for Unified Modeling Language. UML is a language standard published by the Object Modeling Group (OMG). See http://www.omg.org

- XMI

- Acronym for

XMLMetadata Interchange. Allows to store UML models in XML format for data interchange. Like UML it is a standard published by the Object Modeling Group (OMG). See http://www.omg.org - XML

- Acronym for eXtensible Markup Language. It is defined in the XML 1.0 Specification.

Bibliography

Bittner, K., Spence, I.: Use Case Modeling. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2002. ISBN-13: 978-0201709131

Cockburn, Alistair: Writing Effective Use Cases. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2000. ISBN-13: 978-0201702255

Kilian, Thomas: Inside Enterprise Architect. Leanpub, 2012. https://leanpub.com/InsideEA

Kilian, Thomas: Scripting Enterprise Architect. Leanpub, 2012. https://leanpub.com/ScriptingEA

Linné, Carl von: Systema Naturae. Leiden, 1729.

Object Management Group (eds.): Superstructures 2.4.1, 2011. http://www.omg.org/spec/UML/2.4.1/

Object Management Group (eds.): Business Process Model And Notation (BPMN) Version 2.0, 2011. http://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0/

Sparx Systems: DOORS MDG Link, 2013. http://www.sparxsystems.com/products/mdg/link/doors/purchase.html

Sparx Systems: RaQuest, 2013. http://www.raquest.com

W3C (eds.): XML 1.0 Specification. Internet, 2010. http://www.w3.org

W3C (eds.): Web Services Description Language (WSDL) 1.1. Internet, 2001. http://www.w3.org/TR/wsdl

This Is Not The End

I know that the matter described in this book is so complex that only a part of it can be touched. I need to be honest: Some chapters in this book might eventually have raised more questions than you found answers. This is no cookbook. And the recipes given will not always be tasty. But if you got the idea, the golden thread, you made it and you can start asking.

For that reason I would like to add a few links where you will get further help.

Feedback

Any questions you have are important. So you should ask them. Feedback is important for you, me and of course all the other readers. So you are encouraged to contact me at

- thomas.kilian@me.com

- You can mail me directly if you have specific questions, think that something is not clearly described, have detected some error, etc. I’m happy about any kind of feedback.

UML

Getting grips of UML can be a hard one. Superstructure is no bedtime reading. One place where you can ask questions is the

You will find quite a number of gurus there which really can help you out.

Enterprise Architect Forum

Probably not necessary to name this source, but anyway:

When you post your questions here you should select the right forum and only post once. Getting help here is most likely the fastest lane you can find. I also post regularly.

Another place is

http://www.linkedin.com/groups/Enterprise-Architect-Sparx-Systems-User-1356/about

Most of the “usual suspects” post in either forums of Sparx and LinkedIn.

Sparx Community

A not so well known source as Sparx itself does not link this on its forum pages:

Here you will find a variety of articles and resources around EA.