Table of Contents

Introduction

“My role is that of a catalyst”, wrote Ricardo Semler in Maverick, “I try to create an environment in which others make decisions”[1]. Semler’s statement may appear simplistic when considering the deep changes that turned the Brazilian machine manufacturer Semco into a pioneer of entrepreneurial self-organisation: from decreasing the number of management roles, to empowering local decision makers, and the transparency of all relevant business data up through employee profit sharing.

For me, Semco´s evolution is one of the most spectacular examples in the history of self-organisation. It seems to be a worthy opening for my new book, which includes many sensational stories. Semler’s catalyst statement emphasizes three core elements of self-organising enterprises. First, it emphasizes the importance of the environment, or context, in which the work occurs. Second, it emphasizes the role of decision making through which we continuously re-organise ourselves. And third, it emphasizes that the decisions are made by the subject matter experts instead of their superiors.

The changes in Semler’s own role over the course of the company’s history are similarly spectacular. After many years as CEO, he withdrew himself from the daily business of Semco. “Now I am just another counsellor. But my job hasn’t changed. I try to make things happen, like a catalyst.”[2]

It’s interesting that Semler affiliated his management and counsellor role with the same metaphor. On the one hand, this double metaphor contains, like brackets, an important period in Semco’s evolution. On the other hand, Semler himself merges two areas that are the focus of this book. Management and coaching are seen as essential services for successful business development. Both services are necessary for developing a work system that is as agile as possible to respond to the rapidly changing market. I believe self-organisation is the foundation of this kind of entrepreneurial responsivity. If we are not able to create a supportive environment, encourage people to manage themselves within clear boundaries, and trust that they will do their best, achieving success will be extremely difficult.

Many companies dream of business agility, but this is impossible to achieve without self-organisation. Clever concepts and management rhetoric are not enough. It needs profound understanding, flexible forms of interaction, and enough stamina for the long journey of incremental improvement. Luckily, self-organisation today is no longer rocket science. There are enough enterprises that we can learn from to find our own way. Semco is only one example of such an enterprise, and you will learn about many others in this book.

The question remains as to why management and coaching should play an important role in self-organising enterprises. What exactly do managers need to do to create such an enterprise? What should the coaches concentrate on to inspire this creation? And which unique opportunities result from combining leadership and coaching?

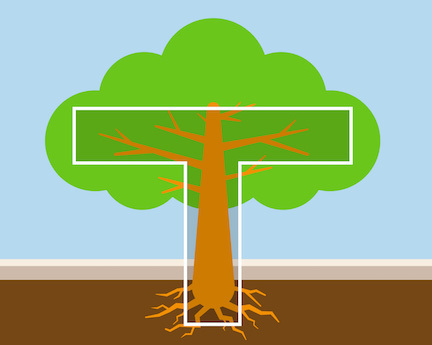

I answer these questions in the four parts of this book. Part I deals with a concept of management that can cope with the challenges of the agile world. I attempt to dispel some myths about agility and self-organisation. After that, I will refer to several topics from my last book, Leading Self-Organising Teams [3], and will show you, among other things, how such teams can continue to grow.

In Part II of this book, I go beyond the individual teams and methods to examine enterprise-wide self-organisation. To achieve this, we can refer to eight design principles, and each will be examined in their own chapter:

- Customer First

- Visual Work Management

- Fast Feedback Loops

- Customized Decisions

- Bold Experiments

- Lean Organisational Structure

- Distributed Management

- Continuous Training

A broad spectrum of practical examples from various industries, contexts and countries should help you to pursue your own change initiative without having to rely on standardized frameworks.

Part III of the book explains why I view coaching as a core skill for such initiatives. First, I will give a solid definition of coaching: What is coaching? What distinguishes this kind of professional help from other forms of support? And what does it have to do with self-organisation? In addition, I introduce four types of support that now belong to the daily business of self-organising enterprises: peer consulting, peer feedback, and coaching managers as well as managers as coaches. Real-life examples help to convey a practical understanding of these concepts.

In Part IV, I focus on the idea presented at the beginning of this foreword from Ricardo Semler. I have even dared to create a short manifesto for self-organising leadership in which I propose that management and coaching should go hand in hand. With regards to this special partnership, I outline a different way of leading and share some personal experiences.

Who can benefit from these four parts? The subtitle of the book, "Management and Coaching in the Agile World", focuses on two target groups. The first target group is line managers who want to create an agile enterprise and know, or at least have an idea, that they need self-organisation and a fresh understanding of management. The second target group is coaches who support such a transformation by using their specific subject matter expertise and process knowledge. It would be even better when a coach reads the management part of this book, just as a manager might dig deeper into the coaching part. Managers are playing an increased role as internal coaches and mentors, and the concept of a sparring partnership between managers and external coaches encourages out-of-the-box thinking.

Because this book advocates leadership at all levels, it has something to offer to many other members of the organisation as well—whether they be technicians, product managers, project leaders or human resources specialists. The distribution of management responsibilities that characterizes a self-organising enterprise, the delegation of decision-making authority, or the peer coaching and feedback are practices that everyone can benefit from.

Why should you keep reading? What do you get out of it? Essentially, you will learn how to take better care of your customers, give your employees a more satisfying work life and at the same time make a respectable profit. Not a bad deal, if you ask me. Specifically, I will describe:

- How you, as a manager, can concentrate on the design of a work system that will be fit for the future. I'll show you how to establish such a system so autonomy is gradually expanded. To achieve this, you will need decision-making policies, fast feedback loops and a smart distribution of traditional management responsibilities.

- How you, as a coach, can help cultivate self-organisation by providing helpful impulses. A careful balance between expert and process coaching is as important as the ability to support, as well as challenge, the managers. For me, one of the obvious consequences of agile transformation is that managers themselves gain more coaching competencies.

- How you as a subject matter expert can create an open atmosphere with your colleagues, but also with management, and take full responsibility for those work areas for which you are accountable.

These three value propositions reinforce my argument that self-organising enterprises are a catalyst for leadership capabilities. However, not all employees are equal in a self-organising environment. If anything, the business value of self-organisation lies in the ability of not only respecting, but also deliberately utilising, the employees´ differences in experience, skill levels and personality. The agile coordination of these differences comprises the lifeblood of self-organisation.

Maybe all of this sounds familiar to you. If that is the case, I hope that insight (and not the devil) lies in the details. Even more, I hope the details in this book will help you with your own organisational design..

It won't surprise you that I didn't invent self-organisation. There are several pioneers that this book refers to. I would like to specifically mention the inspiring work of Brian M. Carney, Isaac Getz, Gary Hamel, Dominik Hammer, Stefan Kaduk, Frederic Laloux, Dirk Osmetz, Hans A. Wüthrich, and the Corporate Rebels Joost Minnaar and Pim de Morree.

Inspiration is also the keyword for the insights I got from the books of practitioners like Hermann Arnold, Corinna Baldauf, Timo Capriuoli, Alexander Gysinn, Klaus Hoppmann, Bodo Janssen, Detlef and Ulrich Lohmann, Tim Mois, Lee Ozley, Ricardo Semler, Rich Teerlink and Götz Werner.

A special thanks goes to all my partners from the various enterprises covered in this book: Sandra Altnow, Gerhard Andrey, Michael Beyer, Peter Hollenbeck, Katrin Dietze, Hans Gruber, Jutta Handlanger, Erich Harsch, Thijs Havenaar, Achim Hensen, Cliff Hazell, Holger Karcher, Marijke Kasius, Werner Kohl, Stef Lagomatis, Benno Löffler, Ulrich Lohmann, Sönke Martens, Markus Monka, Thu Pakasathanan, Matthias Patzak, Clemens Riedl, Arne Roock, Hartger Ruijs, Michael Rumpler, Peter Stämpfli, Frank Schlesinger, Alexander Schley, Markus Stelzmann, Eva Stöger, Nicole Tietz, Stefan Truthän, and Carina Visser.

I would also like to thank these brave people who worked through several versions of this book and significantly influenced it: my brother in agile arms Klaus Leopold, my editor Christa Preisendanz, my translator Jennifer Minnich, my dear friend and intellectual companion Georg Tillner, and last but not least Sabine Eybl, my business partner and love of my life.

I dedicate this book to our two daughters — with the hope that they´ll find more opportunities and less restrictions both in society in general and in the business environment in particular.

Part II Scaling Self-Organisation

"What do you mean with scaling?" my younger daughter wanted to know as she was glancing at the preliminary table of contents. "It means expanding the concept of self-organisation, ideally to all areas of an enterprise", I answered. "That means there are just more employees and teams that decide for themselves what they do?" "Well, yes and no", I responded, "what you say is true, but it also isn't that simple."

The blank look my daughter gave me at the end of this fleeting visit was what I would call a typical reaction. The topic of scaling can easily cause confusion. It is complex, has a tendency to bewilder us, and eliminates simple cookie-cutter solutions such as "double the number of teams", “install Holacracy” or "implement Agile methods in all departments". Despite all the flexibility that goes along with self-organisation, it is not a mix-and-match collection that you can combine however you like. Self-organisation is, and remains, challenging. A supporting context, clear boundaries, a good mixture of diverse people, and an open exchange between them are essential factors for its success.

These fundamentals remain the guiding principles if we talk about self-organisation across the entire enterprise. But what is needed to develop the existing potential within the organisation? Where do we begin if we want to combine the capabilities of all employees in the best way possible? And which methods have proven themselves worthwhile?

Just like at the team level, certain myths at the organisational level distort the more reasonable answers:

- The myth that an agile enterprise automatically results from the sum of all agile teams.

- The misconception that we can use methods for agile software development in every department.

- The assumption that we can anchor self-organisation within the enterprise by using a blueprint model fresh off the drawing board.

- The illusion that agility can be ensured by assigning special roles to employees.

Without question, business agility is a hot topic at the moment. Faster, more lightweight, more flexible is the creed for all companies who want to respond to the current challenges. If even the CEOs of industry giants such as Deutsche Telekom are concerned about agility, they appear to have set the course for a better future. At the same time, it cannot be ignored that applying agile means nothing more than local initiatives in many cases. Software Development increases their output while the chaos in the rest of the company worsens. Production drastically reduces their cycle time, but the total time to market remains unchanged due to the overall coordination issues between departments. There are innovative ideas, but the fast feedback loops of design thinking are limited to a few experts. At the end of the day, none of our agile ideas changes anything for the customer at least not for the better. They may even have to wait longer for the promised products and services.

There appears to be an invisible barrier in many enterprises that reminds me of something written by Austrian poet Johann Nestroy: Thoughts are free—as long as they remain in the mind. Isn't it also true that agile initiatives remain free only as long as the initiative remains at the team level? Is it just a coincidence that agile initiatives remind us of Gallic villages where magicians are mobilized, but the enterprise remains firmly in the hands of the Roman empire?

Fact is enterprises are not made up of teams alone. More importantly, successful self-organisers apply more than one approach rather than believing there is a one-size-fits-all method that can deal with every challenge. Very few of the companies I looked at work with ready-made frameworks that just need to be correctly implemented in the problem area. Even fewer of these companies attempt to ensure agility through an alternative organisational structure. Which raises the question about what action can be recommended if we want to see self-organisation grow within our enterprise. What must we do if we want to customize our system rather than applying scaling templates? Which elements encourage an organisational design that is fit for the future? And how can we use the entrepreneurial spirit throughout the organisation for this?

It makes sense to answer these questions not just theoretically, but with practical examples. Fortunately, finding such examples is no longer like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack. There is an abundance of sources with specific examples from which we can gather information. Thus, I have collected, from the gamut of available resources, insights from business literature, interviews with practitioners, as well as my personal coaching and consulting experiences. I am not concerned with providing an encyclopaedia-like overview, nor about giving anecdotal case studies. Instead, I would like to explore the variety of entrepreneurial self-organisation in order to find out the best practices. What works well? Which design elements are used again and again? How do the various companies proceed? And how can they recognize if this approach is worthwhile?

Table II-1 documents the different contexts, industries and countries where enterprise-wide self-organisation is used.

| Company | Industry | Country | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES | Energy | USA | 21.000 |

| AllsafeJUNGFALK | Load Restraint | Germany | 200 |

| AutoScout24 | Online Car Sales | Germany | 400 |

| AVIS | Car Rental | USA | 30.000 |

| Buurtzorg | Nursing | Netherlands | 10.000 |

| bwin | Online Gaming | Gibraltar | 3.000 |

| Compax | Software Dev | Austria | 140 |

| Computest | Software Test | Netherlands | 120 |

| dm | Drugstore | Germany | 38.000 |

| eSailors | Online Lottery | Germany | 130 |

| Finext | Finance | Netherlands | 140 |

| FAVI | Metal Processing | France | 400 |

| Gore | Clothing | USA | 10.000 |

| Handelsbanken | Finance | Sweden | 11.000 |

| Harley-Davidson | Motorcycles | USA | 5.900 |

| Haufe-umantis | Software Dev | Switzerland | 130 |

| hhpberlin | Fire Safety | Germany | 160 |

| Hoppmann Auto | Car Sales | Germany | 460 |

| IDEO | Design | USA | 600 |

| ImmobilienScout24 | Online Platform | Germany | 600 |

| Incentro | Software Dev | Netherlands | 285 |

| InVision | Software Dev | Germany | 150 |

| Jimdo | Software Dev | Germany | 200 |

| LIIP | Software Dev | Switzerland | 150 |

| Morning Star | Tomato Products | USA | 600 |

| Menlo Innovation | Software Dev | USA | 180 |

| Patagonia | Outdoor Clothing | USA | 1.100 |

| PKE Electronics | Software Dev | Austria | 1.100 |

| Richards Group | Marketing | USA | 680 |

| Semco | Manufacturing | Brazil | 1.000 |

| sipgate | Telecommunication | Germany | 120 |

| SOL | Cleaning | Finland | 11.000 |

| Spotify | Music Streaming | Sweden | 2.500 |

| Stämpfli | Communications | Switzerland | 410 |

| Synaxon | Networking | Germany | 130 |

| Swiss Railways | Travel | Switzerland | 29.000 |

| TELE Haase | Relays | Austria | 85 |

| Traum-Ferien | Travel | Germany | 120 |

| Toyota | Automotive | Japan | 300.000 |

| Upstalsboom | Travel | Germany | 680 |

| USAA | Finance | USA | 26.000 |

| Volksbank Heilbr | Finance | Germany | 320 |

| Whole Foods | Supermarket | USA | 40.000 |

| Zappos | Online Shopping | USA | 1.500 |

This table is comprised of pioneers such as AVIS, Gore and Semco, trendsetters like Patagonia, Morning Star, Upstalsboom and Spotify, as well as aspiring newcomers such as sipgate, Computest and Haufe-umantis. It lists enterprises with anywhere from around one hundred up to several thousand employees where self-organisation has been implemented to varying degrees. It contains companies with spectacular success stories, but also examples such as FAVI or Jimdo, where freedom and autonomy are now history. Self-organising enterprises are not protected from fundamental changes — whether it be changes in ownership structure, new top management or hard cuts and turnarounds. For example, energy company AES, a self-organising pioneer since the 1980s with over 40.000 employees, experienced such a turnaround in the 2000s.

The more companies I looked at, the more intrigued I became in what I was seeing. Self-organisation was like a kaleidoscope where colourful pieces were continually creating new images. However, a few characteristic patterns repeatedly emerged. As different as these examples may appear, they are very similar in their approach. When comparing the various enterprises, I discovered a surprisingly consistent set of principles and practices had been implemented. Following is a brief summary of the principles and practices, which will be explored in depth later.

- Customer First. In any company where self-organisation was successfully scaled, the customer has been the focal point. The customers' perspectives, interests and needs are the centre of business. This is reflected in the framework of an enterprise, whether it be a powerful mission statement, strategic direction or guiding principles for a long-term company vision. It is also reflected in the way things are done when having a customer-oriented portfolio.

- Transparent Work Flow Management. Smoothly running processes are necessary to best serve the customers. We want to create value rather than just keep ourselves busy. Value can only be created if all essential activities are properly coordinated. However, this coordination has less to do with organisational structure and more to do with work flow, from the first input up to customer satisfaction. Transparency of this flow and its ongoing management not only provides the best quality, but also a high degree of reliability for the customer.

- Fast Feedback Loops. The quality of decisions is directly related to the quality of feedback we receive. Without accurate feedback, our management efforts are doomed to failure. Managing complex work can seem like pinning the tail on the donkey. Self-organising enterprises use a proficient system of meetings, metrics, and personal feedback to make this task easier.

- Customized Decisions. Managing the value stream can only succeed if we make the right decisions. To go back to my boat metaphor: Only if the wind and sea conditions are favourable, the sails are let out and the rudder is correctly set, is it possible for the enterprise ship to set sail. In order to pool our strengths, new decisions have to be made repeatedly in many areas. In a self-organising enterprise, the necessary authority for these decisions is delegated to those persons with the highest subject matter expertise and situational knowledge. The hierarchical position is no longer crucial, but rather the proximity to the work that is affected by the decision.

- Bold Experiments. Agility does not mean than we are safe from failure. Quite the contrary: Incremental improvements, just like breakthrough innovations, require trial and error. Not only do you need good feedback, you also need a culture for dealing with failure that supports experimentation. And there needs to be a learning culture that constructively deals with any tension or conflict that arises.

- Lean Organisational Structure: Self-organising enterprises thrive on the autonomy of their business units. Loosely coupling these units empowers them and facilitates flexibility. This is why many enterprises are set up according to customer needs, with flat hierarchies and minimal staff functions.

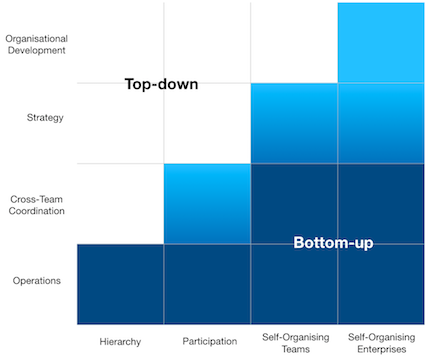

- Distributed Management. There are at least two consequences from the points discussed so far. One, traditional management responsibilities in self-organising enterprises are distributed amongst many people. Second, the responsibilities of line management change. The difference between working on the system versus working in the system is quite eye-opening. Subject matter experts in the subsystems enjoy wide-ranging autonomy, while line managers ensure clear boundaries, a supportive context and appropriate coordination.

- Continuous Training. Self-organisation did not develop on its own in any of the companies listed in the table. Miracles only happen in fairly tales. The reality is that self-organisation needs profound information (keyword: transparency), consistent empowerment (keyword: skill building) and disciplined practice (keyword: routine) in order to master new challenges.

As mentioned, I discuss each of these design areas in greater detail in the following chapters. Along with a detailed discussion of each design area, I describe the management tools used in various companies. Specific examples will illustrate how these tools are applied and give you a better idea how you could use them for your own business.

1 Customer First

"The only thing that bothers us is the customer", as the saying goes. Anyone who thinks this is just a cliché should take a look around. Customer trouble is still very much alive, especially in large enterprises. The day-to-day business is overloaded with tasks, work is broken apart by constant changes and line management adds additional uncertainty due to micro-managing. The fact that many companies willingly outsource their customer support speaks volumes. Instead of seeing their customer service as a valuable feedback loop, it is delegated to a call centre where the primary goal is efficient processing. The call centre agents do not concern themselves with the relationship between company and customer, nor do they provide feedback on this relationship to the company. Rather, they are used by the companies to keep the customers off their back.

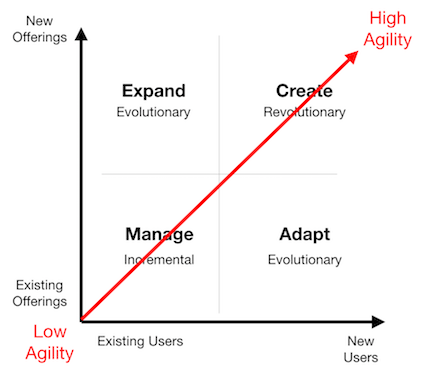

Everyone is talking about agility, especially those who complain about market volatility. They want to reduce complexity, and dream of shorter response times. The brave ones apply Scrum and Kanban in more and more areas to achieve these goals. Some even see themselves as an agile enterprise because they have agile teams. At the same time, very few of these enterprises place the customer first. Instead, their organisational agendas remain focused inward. Local optimization (i.e. so-called high performing teams) and tactical action (i.e. performance management) are the order of business.

It's easy to forget, in light of such a mindset, that even the largest companies once started small. Today, we refer to them as startups. Despite many constantly changing factors, one law remains the same: companies can only survive if they have customers — and can only grow if the number of customers, along with their willingness to spend money, increases. When founding a company, it is completely normal to focus the company's actions around the customer. You know the customer, understand their needs and how to generate revenue from it. Otherwise, the company's development is over before it starts.

But how can a company keep its customer focus when it is no longer in its startup phase? How, when it's no longer a so-called garage-based business, but rather an enterprise with a growing number of employees? How, if it gradually starts becoming more concerned about process guidelines or standards of conduct rather than on activities that have value for the customer?

I am going to give you three answers that define the state of each enterprise: the mission, the vision and the strategy.

1.1 Mission and Vision

Why does our company exist? This is the fundamental question that a so-called mission statement answers.

Before you start writing your statement, there are two things that you should consider. First, how can you make sure that your mission statement drives the company, versus just being a piece of paper? Second, how would you like to develop this statement? Are you just going to dictate it from the top? Will you consult with certain colleagues? Maybe you will even have customers validate your value proposition?

The way in which you answer these questions could also reveal something about your understanding of management and your corporate culture. Regardless how large the organisational unit where the mission statement is intended, it should be a concise summary regarding the "what" and "why" of your work. Perhaps some practical examples would help? The mythical motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson states, "We fulfil dreams through the experiences of motorcycling, by providing to motorcyclists and to the general public an expanding line of motorcycles and branded products and services in selected market segments". The supermarket chain Whole Foods writes, "Whole Foods Market is a dynamic leader in the quality food business. We are a mission-driven company that aims to set the standards of excellence for food retailers. We are building a business in which high standards permeate all aspects of our company. Quality is a state of mind at Whole Foods Market. The Swiss software developer Liip created a manifesto around their core values of agility, innovation, sustainability and fun. Besides the adaption of the manifesto for agile software development, you will also find some basic beliefs regarding web and development: the view that our current culture is determined by the internet, that it is imperative to invest in the company and in people equally, using Open Source technology, or the commitment towards innovative projects which foster the unique capabilities of the customers. And at outdoor specialist Patagonia, all of their activities consistently revolve around their mission statement to "Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis".

The Dutch nursing network Buurtzorg also started an ambitious undertaking:

"Improve the service and quality of home care through guidance and cooperation with local nurses, allowing every person to receive the type of care they need the most at the place they prefer to be—avoiding expensive institutional nursing care for as long as possible."

The Californian tomato company Morning Star even has four different mission statements: at the company level, between the autonomous divisions, in each operational unit and for every individual employee.

- The personal mission statements form the backbone of the company. They describe how each person contributes to the company's success.

- In a so-called CLOU (Certified Letter of Understanding), agreements between colleagues who work closely with one another are summarized. The majority of employees have approximately ten such CLOUs in which results, goals and metrics are stipulated.

- Every two months, the achieved results are used to compare the actual performance to the planned performance in the CLOU and, if necessary, take corrective action. The CLOU is transformed into a type of guidance system for the activities, instead of simply becoming a bureaucratic task.

- The same coordination principle is also used between the various departments and divisions, weaving each employee and each subsystem into a dense network of commitments. However, the network is not dictated by hierarchy, but instead is negotiated between colleagues. This is the main point of personal responsibility at Morning Star. "Make the mission your boss" is the motto [1].

Making a mission statement into something operational is important, because they often suffer the same fate as corporate values or principles. The mission statement lists a number of buzzwords, and leads a miserable existence plastered on the office walls. If carefully implemented, however, it can provide a high degree of clarity: It outlines what is expected from every individual, what they are supposed to do and how they contribute to the overall enterprise. According to Jean-Francois Zobrist, well-formulated mission statements help us go from being a "how" company to a "why" company. For the former CEO of the self-organising pioneer FAVI, it is not necessary to constantly tell someone how to do their job. By concentrating on plans, regulations and standards, you are occupying your time with everything other than what really counts, which is whether or not the work is completed properly and if the customer is satisfied. In comparison, "why" companies replace the proliferation of standards by one single question: "Why do you do what you do?" As long as the answer is, "To make the customer happy", according to Zobrist, there is no need to give any thought about how exactly that is accomplished [2].

If the mission explains the existence of your company, and gives each individual clarity about how they contribute to its success, then full speed ahead. But what is a vision then? Is it not the same thing? Although mission and vision are often interchanged in practice, there is a one main difference. While the former drives your business operation, the latter defines your higher aspirations. A vision should not be confused, however, with operational targets. Instead, it frames an idealized picture of your company's future.

- What do you want to accomplish in 5/10/x years?

- How will your business area look then?

- Who are your customers? What value will you deliver to them?

- What distinguishes your organisation? What separates you from your competition?

A well-formulated vision communicated to everyone can serve as a kind of guiding star, turning the focus towards the big picture when making decisions. Perhaps the most famous example of such a guiding star is Toyota's True North: zero failures, 100% value added, one-piece-flow, overall work security (mental, as well as physical) and professional challenges (meaning continuous improvement). At first glance, it is obvious that this vision can never be achieved. It is too strongly based on the superlative. Relentlessly striving for perfection, though, always spurns new improvements and ensures sustainable economic success, as Toyota has impressively proven despite various crises.

Companies in completely different sectors also understand how to set the bar high. The Finnish cleaning specialist SOL, for instance, formulates the vision of an outstanding service provider. "We want to be the best operator in the field of environmental issues, both for our customers and our personnel." Although this objective seems inconspicuous, it is quite ambitious since they are using chemicals on a daily basis. On the other hand, Zappos predicts., "One day, 30% of all retail transactions in the United States will be online. Consumers will buy from the company with the best service and the best selection. Zappos.com will be that online store."

Harley-Davidson has a vision which places an emphasis on two areas: "to continuously improve our mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders (customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, government and society)" and on the "empowerment of all employees to focus on value-added activities".

1.2 Strategy and Culture

Both mission and vision are ineffective without a coherent strategy. If you offer unattractive products and services, it makes little difference if you are self-organising or not. The same goes if you chase after a guiding star that doesn't shine. The customers will be as indifferent as your value creation. How can specific strategies be created that will pool existing strengths? How can you prevent these strategies from becoming costly ceremonies, like those celebrated all over the country by the large consulting firms? How can you set powerful objectives instead? At their peak, the Hamburg-based website specialist Jimdo was a perfect example of how strategy development can be done in a way that systematically uses the potential of self-organisation. The main idea was based on consistent focus. Goal #1 became whatever was currently promising the greatest value. This goal was not, however, simply given out and then monitored behind closed doors. Instead, delegates from all areas met at regular intervals in order to exchange information and to ensure effective coordination of everyone involved [3].

For strategy-oriented coordination in a self-organising enterprise, the swarming method has proven itself useful. These swarms are used anywhere the company has a complex business problem to solve. Similar to a swarm of fish, those persons having the necessary expertise for a solution self-organise themselves into a group. With adequate training, the swarming needs neither special facilitation nor a dedicated management to allocate resources. At personnel software expert Haufe-umantis, swarming can even be found at the strategic level. In the research and development area, there are around 60 self-organising employees that get together to pursue, from their point of view, the best value proposition. How does it help the customer to work even more successfully? What brings the greatest benefit? And how can we manage it? Every three months, these questions are worked on together so the available resources can be pooled in the best way possible. Fixed departments are as rare as classical managers in the research and development area. Harley-Davidson builds on something similar. Their "natural working groups" are organized into three segments and are geared towards bringing the right people together to implement projects with great potential. The employees find themselves within certain product, support or marketing circles to find appropriate solutions for the customer.

The Dutch nursing network Buurtzorg impressively demonstrates how an ambitious mission can be combined with a clear strategy. This strategy is comprised of six components [4]:

- Assessing the patient's needs. This is done holistically, and includes medical, social and personal concerns. Based on this assessment, an individual care plan is drafted.

- Gathering all the informal networks and their contribution to the care.

- Identifying the official caregiver and their involvement.

- Implementing the care.

- Supporting the patient, thus allowing them to exercise their social roles.

- Promoting independent care and personal independence.

These strongly bound components set the framework in which the private and professional nurses provide their services.

The question remains, though, about how you can assure the customer remains at the centre of your strategy. The answer to this question can vary, because self-organising enterprises themselves are quite diverse. The one thing they have in common is the consistent inclusion of the employees. Instead of making strategy exclusively a management responsibility, it is instead based on the experiences and ideas of those who are usually much closer to the customer. This can occur, as it does at sipgate, in a group composed of people from a range of departments and hierarchy, who regularly meet for strategy workshops. Or it can include all employees, like at eSailors, who meet quarterly for an overall review and planning meeting. Or, in the case of Computest, through a group delivering company-wide services, managed with a so-called discovery board.

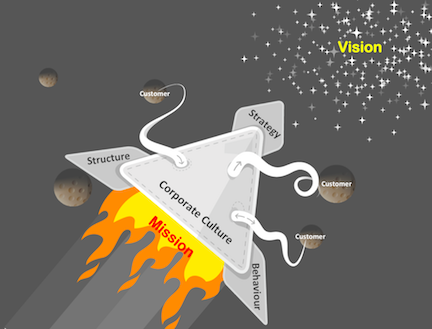

Figure 1-2 shows my comparison in picture form. Furthermore, the picture solves the puzzle of what the spaceship should be named.

The importance of culture hardly needs to be emphasized in agile environments. "Culture is the true North Star," notes Arne Roock, which is obvious in many self-organising enterprises [5]. For business success employee satisfaction plays as equally a vital role as customer satisfaction does. And culture is often used as an argument for employee satisfaction. So far, so good. Figure 1-2 underscores, though, that this culture cannot be reduced to atmosphere, climate, spirit or something similarly vague. It emerges more as a result of the dynamic interaction of strategic, procedural and behavioural factors. The easiest way to translate the cumbersome concept of corporate culture, underlining this interaction, is "this is how we do it here”: this is how we see the market, this is how we perceive the challenges, this is how we work together, this is how we serve our customers, etc.

Corporate culture is not a single factor. It is not the product of the interplay of strategy, structure and behaviour. Thus, it is a broad and deep phenomenon that governs our thinking, feelings, actions. That is why changing the corporate culture is a costly and time-consuming undertaking. As dm´s CEO Erich Harsch points out, we cannot simply "flip a switch. Changing culture takes years." This change will be driven, according to Harsch, by two inseparable principles: through a customer-oriented stance and through the appreciation of individuals. The principle is, "customer first, and success will follow". This only works, though, if the individual isn't simply seen as a way to maximize profits. "If I treat my employees poorly, I shouldn't be surprised when they treat the customers poorly."

The power of corporate culture does not come as a surprise for Peter Stämpfli, president of the board of directors at communication service provider Stämpfli. On the contrary, the step-by-step transformation of the long-standing company towards more autonomy is hard to imagine without the existing foundation of equality and commitment. According to Stämpfli, this foundation is extremely important for answering the pressing questions of today: What challenges will the company face? What will be the effects of the ubiquitous digitalisation in various areas? And, as Stämpfli states, can "a different synergy between awareness and interaction" be achieved? More decision-making autonomy within clearly defined boundaries is one of the answers they are currently working on. Stämpfli is convinced that additional answers will lead towards a more agile leadership philosophy. Regardless how many more change experiments will be needed, the motto remains the same: Communication – person to person. And this motto, built on respect and trust, will continue to apply to employees as well as customers.

Harsch´s and Stämpfli´s ideas underscore an additional risk that accompanies every change of corporate culture, namely the risk that employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction will be separated from or even pitted against one another. Does the customer or the employee come first? Do we want to do a better job or create a good working environment? Do we want to embrace more business opportunities or cultivate new ways of working? It goes without saying that employees are the most valuable asset of an organisation. Without their experience and capabilities, without their commitment and business intelligence, we cannot achieve a single benefit of agility. This requires us to foster every type of corporate culture, whether it be treating each other with respect, exciting challenges, attractive conditions or a powerful employer brand. At the same time, it is important to retain the best employees over the long-term and win the war for talents.

On the other hand, we should not ignore that neither human nor technical resources can be used effectively if there is too little demand. If we want our business to develop, the unavoidable question is how we retain our regular customers while gaining new customers. How do we consistently align our corporate culture to the customer? Which structures and processes are needed for this? How does this affect the behaviour of the employees? How do we strategically align these behaviours? And, in turn, what effect does this strategy have on our structures and processes?

1.3 Design Thinking

I know these questions will be like opening up a can of worms. Almost 15 years ago, Henry Mintzberg already warned us about the adventures awaiting us in the jungle of the strategy industry [6]. But, with all due respect, I would like to wrap up this chapter by briefly taking a look into this jungle. Self-organising enterprises are not spared from the strategy safari, so how can you avoid getting lost in this concept jungle?

Based on what has already been stated, the answer is straightforward: Every strategy safari that has real discoveries in sight must inevitably lead us to the customer. However, it begs the question how to best make this journey, and at the same time learn something from it that benefits from our corporate culture. To navigate this journey successfully, I recommend using Design Thinking, which has significantly influenced how to develop an organisational strategy since the beginning of the 2000s [7].

Design Thinking was initially meant for the early phases of generating ideas, but has since been used in many business areas: the entire product development cycle, the introduction of various services, strategy development, as well as organisational design. Moreover, Design Thinking pioneer IDEO has been using this method in developing countries for several years.

Since its start, Design Thinking has left its mark on many companies. It can be seen in new products or services. It can also be seen, though, in the change initiatives, innovation forums or strategy discussions. Invariably, the same issues always have to be addressed. Issues such as how to raise the awareness of each employee, how to use their knowledge and experience, or how to transform these forces into promising initiatives.

The interdisciplinary and iterative nature of Design Thinking makes it a close relative of agile methods. On the other hand, the focus on customers, the experimental nature and the prototype-focused approach are in the tradition of lean thinking. And without self-organisation, without the willingness to intensively communicate across many areas and test new methods, every innovative endeavour is already on the wrong path.

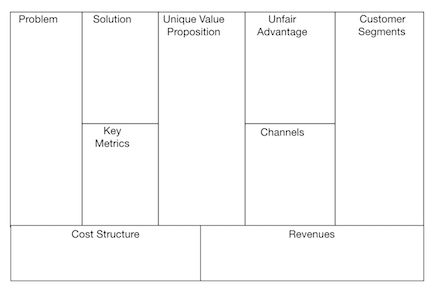

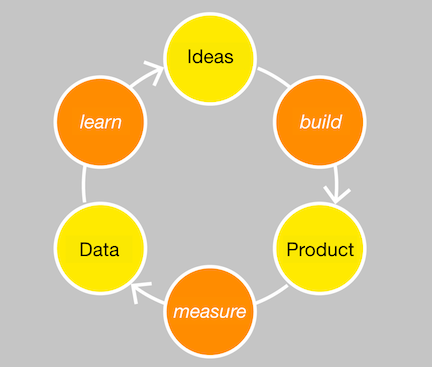

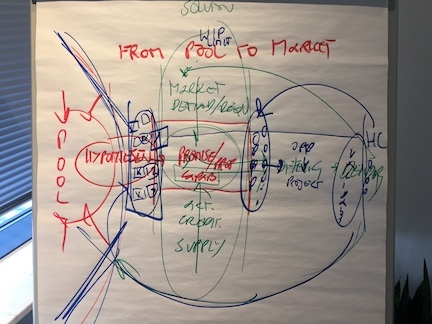

At the same time, Design Thinking inspires new practices in all of these areas. Ash Maurya's Running Lean concept appears most promising in this regard [8]. Maurya starts with the classical innovation questions: Are the customers interested in our product or services? Are they also willing to pay for them? And how difficult is it to actually develop and deliver? The answers to these questions are driven by a Unique Value Proposition. In the area between problem and solution, this proposition outlines how the customer benefits from our idea. Before we do our best to get this idea to market, however, we should also do some homework. Which channels do we want to use to distribute our product? What does it cost to provide a specific service? What type of revenues are we expecting? And how do we know if we heading in the right direction? To prevent us from going crazy with so many questions, Maurya offers us a simple template to keep an overview of our most important answers. Figure 1-4 shows his so-called Lean Canvas, which can be used as a template for the entire innovation process.

The canvas alone does not eliminate all of the questions we are confronted with at the beginning of any innovation cycle. However, it helps to keep an overview of all the relevant factors when dealing with three business-critical risks:

- Product Risk: Which problem are we solving? What needs are being met with it? What would a minimally viable product (MVP) look like, which allows us to test our idea with minimal cost?

- Customer Risk: For whom exactly is the problem we have identified a concern? For whom is it so important that they would be willing to pay for a solution? How do we find those who are ready for it right now?

- Market Risk: How is the problem being dealt with currently? What other solutions are already available? What price can we charge for our solution?

For effective risk management, Maurya recommends that we don't rely on typical data gathering. The number of clicks, the usage time or simple sales figures tell us little about the actual customer experience. Instead of vaguely interpreting these figures, we would be better off having direct contact with the customer. He recommends three specific formats for this: the problem interview, the solution interview and the interview regarding our MVP.

Regardless of your specific business hypotheses, prototypes or interviewee partner — the direct interaction will help you gain crucial insights with minimal effort. Interviews are a simple means to continuously collect data in an iterative way. Instead of pondering too long over ideas, sitting forever in internal innovation workshops and keeping yourself busy with your own product versions, you should follow the basic principle of business agility: customer first!

The next chapter will give you information on how you can successfully implement your business ideas. If your company is not a startup, the innovators are forced to compete with existing offers. Which begs the question as to how you can make sure your innovation initiative doesn't just get started, but can be finished within a reasonable amount of time without negatively affecting your current cash cows. How can you manage such a balancing act? How can you secure enough resources for new initiatives when the existing work itself requires so much? How do you continue to improve? And how do you monitor all these things?

Key takeaways from this chapter

The title of the first chapter on scaling self-organisation points out the course of action: customer first. This course of action is reflected in the mission of a company, as well as in their vision or the strategy they use to follow this vision. If it doesn't add value to our customers, it doesn't count.

In the introduction to this chapter, you get an overview of the companies that were examined. Following that, specific examples are given of how companies focused on their customers. It's interesting to see how customer focus is done in companies of various sizes, histories or sectors and how it leads to a unique corporate culture.

State-of-the-art methods, such as Design Thinking or Lean Canvas, reiterate the idea that a customer-oriented corporate culture is not just important for the current business. Such a culture also leads to new products and services that, now more than ever, depend on agile interactions with the market.

2 Visual Work Management

Traditionally, management operates behind closed doors. In various meetings, program managers, product managers or line managers get together to discuss key figures — be it the state of completion, cost efficiency or resource allocation. Doing this fosters tunnel vision: little attention is paid to anything beyond the functional organisation. Because of this, management of customer-oriented value streams remains largely non-transparent; not entirely clear in the best case, and completely obscure in the worst case.

How do self-organising companies manage their work flow? How do they deal with the complex and mostly invisible dependencies of knowledge work? And how do they overcome the chronic lack of communication that paradoxically occurs from an overflow of information? From my experience, which I also wrote about with Klaus Leopold in Kanban Change Leadership [1], you get the best answers with the help of visual work management systems.

2.1 Kanban

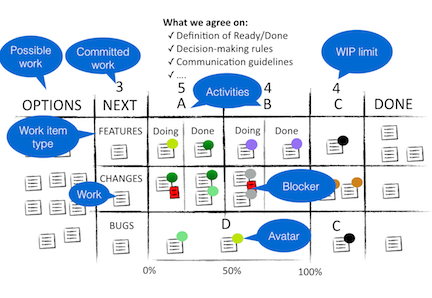

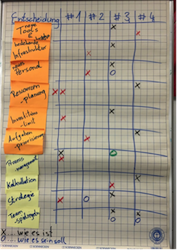

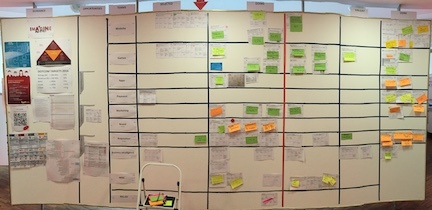

Visual work management helps us visualise what is normally invisible. Complex processes become transparent when we use simple practices to represent our daily work. Figure 2-1 shows a sample of such a representation, which manifests itself as a physical board. Such a board shows us many elements:

- All the work we are currently working on (small squares).

- The types of work there are (for example, features, changes, or bugs).

- The characteristic activities that the work goes through before it's completed (denoted abstractly as A, B and C between the columns of Options and Next on the left hand-side and Done on the right hand-side).

- The maximum number of work items that can be in each activity at one time—regulated by the so-called WIP limit (see the numbers above the columns).

- The quality criteria that are assigned to each activity (definition of "Ready" or "Done").

- Who is busy with what (according to the avatars used, represented by coloured dots here).

- Work that is blocked (shown as little red squares).

- How many activities have already been completed on each work item (according to the work flow).

What does visual work management have to do with flow? With Kanban, it's about having processes that flow as smoothly as possible—and overcoming the inherent risks in these processes. We want to manage our work with our eyes open, channel it correctly, recognize necessary changes early and take care of them as fast as possible. The emphasis is placed on the "We" because Kanban makes everyone working in the system responsible for its management. It isn't just a coincidence that a key principle in Kanban is encouraging leadership at all levels.

Visual work management systems support shared responsibility in many ways:

- It brings work and management together: those that operate the system also manage it.

- For logical reasons, the people managing the work flow are also involved in the design of their management system. The design should be created by those who work in the system rather than dictated by hierarchy.

- External stakeholders only influence this self-organising dynamic by coordinating the input queue. Customers, or customer representatives, determine the what, but the how is defined by those who operate the system. Micromanagement destabilises the system as much as every stakeholder does when attempting to bypass the rules.

- The conscious limitation of all parallel work from arrival (see "Ready" in Figure 5-1) across the entire work flow (see the value-generating activities "A", "B" and "C") up through departure (see "Finished") helps the operators keep their system stable and predictable.

- The system operators are empowered to make all decisions relevant to the workflow, such as handling blockades, dealing with bottlenecks or analysing customer feedback.

- The necessary feedback loops are also created together. How often do we need to synchronise with whom about what? Which metrics make sense? What do we want to communicate to the outside? With whom should we regularly coordinate our efforts?

All work follows some kind of flow. This is why it is so important to keep an eye on the quality of this flow. You can certainly manage a flow-based system without Kanban. As soon as we treat our work process as a series of value-generating activities, we are already on our way. The crucial point is not the method, but the logic behind it; namely, the logic of defining the enterprise in terms of customer-oriented flow instead of internal organisational structures.

2.2 Flight Levels

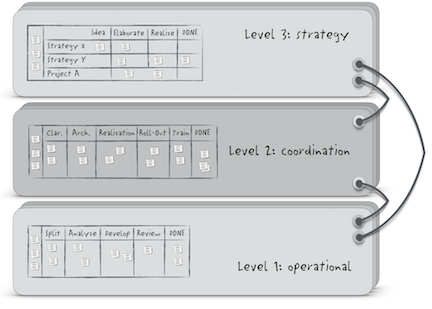

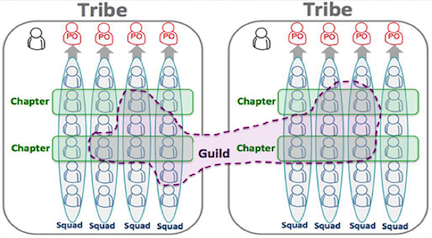

Experience has shown that we can make our management lives easier with Kanban. This applies to subject matter experts, who can see their work in a new light, the same as it does to line managers, who suddenly have the black box of daily business illuminated. Above all, visual work management systems provide an outstanding service when dealing with enterprise-wide self-organisation. My colleague, Klaus Leopold, shows how we can setup such systems (Figure 2-2) with his Flight Levels model [2].

Basically, each level uses the same core practices and principles. Just as you can see in the above figure, it means tailoring the various elements to fit your needs. This applies to the operational board of individual teams (Flight Level 1), the cross-team coordination of the entire value stream (Flight Level 2), and the system that illustrates the portfolio of a business area (Flight Level 3).

Klaus Leopold emphasizes that these Flight Levels are not a capability maturity model: Flight Level 2 is not twice as good as Flight Level 1, and also cannot be refined into Flight Level 3. Although it has to do with transparent management, each level addresses special challenges. For instance, the flow of tasks in daily operations, the creation of value across various units, or the focus on company performance based on a good mixture of projects, services or innovation initiatives.

The various Flight Levels are, however, very much associated with different levels of effectiveness. Kanban can be implemented well at the operational level of teams or departments, but the potential for improvement is much higher at the coordination or strategy level. Flight Level 3 inevitably has an effect on many, if not all, areas. With the help of professional visualisation, we could even gain an overview of the whole enterprise at this level. And this is where the decisions are made that have far-reaching ramifications for our business. How do we handle the gap between the existing business opportunities and our current capabilities? How do we choose the most promising ones from our pool of options? And how many initiatives can we work on at the same time, in light of our limited capabilities? All in all, Flight Level 3 deals with "making prudent choices and combination of projects, developing products and strategic initiatives, recognizing dependencies and optimizing the flow through the value creation chain with the currently available resources" [3].

Of course, the Flight Levels do not force us into an either-or scenario. The various levels can be connected to one another, like the brackets in Figure 2-2 suggest. A strategic portfolio can easily use Kanban for the entire value stream, which in turn supports any number of operational teams. In specific cases, special projects that have no need for coordination can be derived from the strategy board —thus connecting Flight Levels 1 and 3.

Nevertheless, it is not inherently necessary that all initiatives monitored on the strategy board work with Kanban. Scrum, or even the classic Waterfall approach, can be used for running your daily business. Ultimately, substantially larger units flow at the portfolio or value stream level than at the team or department level — strategic options like "less consulting and more service at the customer" and "international expansion of our platform in three countries". While strategic options are chosen at Flight Level 3, Flight Level 2 helps monitor the progress of larger work packages, which are split into individual tasks and executed at Flight Level 1.

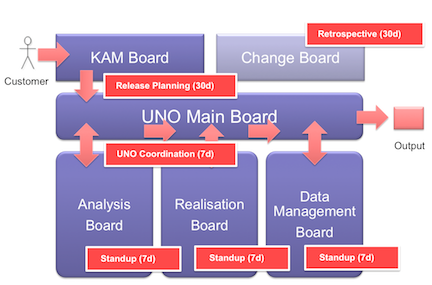

The UNO (Unified Network Objects) department at the Swiss Federal Railways is a great example of how a system can operate over two Flight Levels [4]. As pioneer in a now enterprise-wide initiative, the department began in 2012 to apply visual work management. What started off as an overwhelming jumble of Post-its visualising all the tasks for the first time, gradually developed into a management system that connected Flight Levels 1 and 2. Figure 2-3 shows UNO´s workflow, starting with customer input via the Key-Account Management Board, monitored on the main board and processed step-by-step on the team boards. Continuously aligning individual activities (see the red arrows) with their main board ensures superior quality of the deliverable object. Internal dependencies, blockades or bottlenecks are identified early on and dealt with together. The frequency of meetings providing regular feedback is denoted in the red boxes: the individual team standups, the coordination of the team delegates, as well as the monthly retrospectives for working on the change board, where all internal improvements are monitored.

This system-wide networking is a good fit for the content that UNO works with. The Unified Network Objects specialists link a large amount of raw data to an information network that is the basis for timetable planning, train prognosis and train control. Overview is an important issue to ensure completeness, quality and consistency of the output. Kanban has benefited UNO in many ways in the nearly five years it has been in use. According to team leader Michael Beyer, following are the most important benefits:

- Rapid Success. Quick Wins encouraged further improvement activities, which in turn have a positive effect on the daily work and keeps motivation high for everyone involved.

- Improved Management. Transparency facilitates better communication with all internal and external stakeholders from UNO. In addition, the principle of stop starting, start finishing helped to optimise both throughput and quality.

- Active Agility. Continuous inspection and adaption to changing circumstances is now a standard procedure. The amount of improvements that have been implemented over the years has impressed everyone involved.

- Cultural Change. Since the introduction of Kanban, employees have gradually become players instead of observers. The shared responsibility for creating value leads to teamwork that is characterized by mutual respect and understanding the big picture. The employees have become active change agents who not only run, but also regularly improve the system. In the best sense of self-organisation, the subject matter experts take on a large amount of management responsibility. They make the necessary decisions and bring new ideas to make UNO even more efficient.

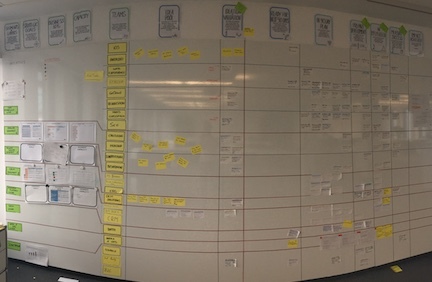

Another practical example shows us how Kanban can be implemented with a focus on strategy. This example is the Kanban board from the German online platform AutoScout24, on which the work for a total of 250 people is represented (Figure 2-4). As a system of the third Flight Level, the board shows us the larger projects, instead of individual tasks, that generate value for the customer as soon as they are completed. In order to assure a good workflow and identify any flow problems early on, the entire value creation process in all relevant customer segments is visualised (see the green cards on the very left). In addition, the individual teams within these segments are represented (see the vertical column of yellow cards). The main activities for the entire workflow across all segments are included on the larger cards running horizontally across the top of the board. In typical Kanban manner, these activities go from an open option pool to an idea generation and assessment phase where the most promising projects are chosen. In addition, these projects are developed using specific success criteria that are checked against the original value proposition. This way, the precise impact of the project is documented.

Since the individual options can vary in size, an overall fixed WIP limit cannot be used. However, too many parallel initiatives will lead to bottlenecks at this Flight Level too, so the WIP limit is always on the agenda at the regular alignment meetings with the representatives of each segment. Along with limiting the initiatives, these meetings deal primarily with four questions:

- What impact did we achieve with our initiative?

- What actual value has been created?

- What is the state of our current initiatives?

- And what can we learn from the overall situation for future use?

2.3 Information and Interaction

All in all, multi-level systems create new design opportunities for any organisation:

- It's suddenly apparent for all people how their own work contributes to the big picture—not everyone may like this transparency, but it allows for more open discussions.

- The personal contribution to overall success is as obvious as the factors that can jeopardize it.

- The systemic effects of individual action become tangible.

- The need for continuous improvement becomes transparent.

- Feedback loops between individual subsystems become faster.

- The entire system can respond more quickly to changes—regardless if these changes are dictated by the market, forced due to strategic initiatives or imposed because of internal problems.

The Flight Levels reiterate the idea — inspired by Russell Ackoff — that an agile enterprise is not the sum of its agile subsystems, just as a team´s success is not the sum of each individual's performance. It isn't enough to just have Scrum or Kanban teams. What's really needed is agile interactions between these teams and the relevant stakeholders of the system. How do we make sure that we are working on the right things at the right time? Who needs to coordinate with whom to optimize the handover? How can we rapidly respond to blockades or bottlenecks? And how do we know if we are really improving? It is important that the entire value stream is considered when answering these questions. Only then can we guarantee our customers also benefit from our self-organisation.

Many companies align themselves along customer groups or product families in order to strengthen their strategic focus. This way, strengths can be pooled, handovers simplified and cycle times reduced. The German load restraint specialist allsafe JUNGFALK had this goal in mind when they eliminated all of their departments—the word department itself means to divide, which prevents flow-based connections. Instead, the company defined customer-oriented processes, which fosters good workflow in all areas.

In many cases, optimising the value stream goes hand-in-hand with its focus. One example is the French automotive parts supplier FAVI, when under the leadership of Jean-Francois Zobrist, that had so-called mini-factories, each focusing exclusively on a specific product or customer. Each mini-factory employed between 20 and 35 workers who had the necessary expertise to be fully responsible for their whole business. And each factory had its own identity, characterised by a colour or customer logo, and was led by a democratically elected manager.

The real estate platform ImmobilienScout24 is a similarly flow-based organisation. Scrum teams that were responsible for development and service were consolidated first into product-type service lines, and later into specific market segments. To ensure mindful management, each of these market segments are led by a cross-functional team from Sales, Product, Marketing and IT. Together, these fantastic four have complete responsibility for the product and business development in their segment.

The online travel agency Traum-Ferienwohnungen is also completely focused on their customers. Each of the five cells of Traum-Ferienwohnungen contains employees from all domains who must work together to provide a high-quality service: customer service agents, software developers, marketing and sales professionals, as well as controllers. The internal coach Achim Hensen states: "In this way, the employees can focus on the requirements of their specific customer group. And they can completely serve the customer from a single source".

Transparent management is inseparable from an open information policy. For instance, the employees of the fire protection experts hhpberlin can access all relevant business data at any time in the CRM system. There they can find information about the progress of current projects, identify new options and connect them by topic. At the same time, the executive management receives a real-time overview of the current situation, has an eye on running costs and can dispatch necessary resources in a timely manner. What IT provides the six locations and approximately 40 competence areas at hhpberlin for a fluid project organisation, is dealt with in a haptic manner and at a single location by allsafe JUNGFALK: partition walls with the relevant key figures, magnet boards with statistical results or blackboards with business information are ever-present. In addition, there is also a strategy wall where all current processes, employees and customers can be found.

Viennese software specialist Compax achieves transparency in a similar fashion: In a monthly newsletter, the executive management communicates all relevant business data, discusses customer projects and introduces new ideas. And Hoppmann Autowelt publishes not only noteworthy business information in their employee newspaper, but also the current profit and loss statements. However, we should not make the mistake of equating pure information with understanding. In many cases understanding is also dependent on expert know-how. Publishing financial figures only makes sense when they can be read and understood in the context of your own work. To achieve this, for example, self-organisation pioneer Semco taught their employees how to read a balance sheet.

Simply imposing self-organisation rarely leads to the desired results. In addition to the basic information of what and why, the how must be designed together. Without open discussion, true commitment will not be achieved. This is also clear to the hotel chain Upstalsboom, which is why culture workshops have become as standard as the breakfasts where ten randomly chosen employees from various departments take part. Workshops and breakfasts help prevent silo thinking and instead encourage exchanges across all areas. The framework supports a deeper learning and understanding of the existing differences: At each workshop, the participants consist of at least 50% new employees across all departments and a maximum of 40% management. This framework provides meaningful exchanges where personal feedback is as important as feedback to the company. And this leads us nicely into the topic of the next chapter.

Key takeaways from this chapter

If companies want to be agile, they need flexible management systems. If they need an eternity to respond to external change impulses, they have already lost. Flexibility is not possible without transparency. Otherwise, it is too difficult to recognize where the company is currently heading and whether or not this course should be modified. Last but not least, companies need to concentrate on workflows that generate value, making customer benefit their top priority.

In this chapter, you learn how a visual work management system (Kanban) can be used to successfully combine transparency, flexibility and flow. Klaus Leopold's Flight Level model allows for such a combination for different purposes: for improved handling of operational tasks in teams or departments, for coordinating value streams across teams or for designing your strategic portfolio.

All Flight Levels exist to utilize the available resources in the best way possible. Because of this, they must align themselves towards maximum customer benefit, limit the amount of parallel work and share the available knowledge. The online platform AutoScout24, the load restraint company allsafe JUNGFALK, the metal processor FAVI or the hotel chain Upstalsboom demonstrate how a company can achieve a high level of self-management without losing control.

3 Fast Feedback Loops

In the previous chapters, I outlined what drives an organisation and how the path towards a vision can be broken down into strategic initiatives and managed with a flow-based system. In this chapter, we want to check if we are doing things right. Do we see how well we are fulfilling our mission? How can we evaluate the quality of our strategy? Which navigation tools are available to us? What do we need to quickly adapt to changing environments? “Fast feedback loops” is the answer to many of these questions. This kind of loop has become the centrepiece of business agility in the last few years. Generally speaking, there are three different types of loops: meetings, metrics and personal feedback. For a thorough description and discussion of personal feedback, please go to Part III, Chapter 1 (not published yet).

3.1 Meetings

Much, if not all, has already been said about agile meetings. If we round up the usual suspects, we will notice a few characteristic features.

Despite the differences between the individual formats, meetings in a self-organising environment all share the following features:

Conciseness: Everything is about coordinating as quickly and precisely as possible, from the classic 15-minute timeframe for Standups, to diverse ad-hoc agreements or the selection of specific topics.

Regularity: Although self-organising enterprises communicate as needed, regular meeting sequences are helpful. On the one hand, regularity ensures that cross-system coordination takes place and on the other hand, they keep the cost of coordination low. This is as important for portfolio planning as it is for controlling product quality. To ensure product quality, interested employees from all areas at sipgate meet every 14 days for a so-called demo meeting to show one another their current results. This meeting is not a work-in-progress report, rather it’s about demonstrating products that have been delivered to customers and are expected to create value.

Focus: Usefulness is naturally the standard measuring stick. What results are needed to make the meeting worth the participants’ time? Who should take part? Or, for the sake of simplicity, who does not need to attend? Focus also means understanding the differences between operational meetings (Standup), strategy-oriented meetings (Portfolio) and learning formats (Retrospectives). In the end, the right people should meet at the right time in the right context to provide an adequate Return on Time Invested (ROTI). In self-organising environments, there are no overwhelming agendas. Instead, a focal point is set such as testing prototypes, assessing business options, working on quality issues or evaluating data.

Directness: Self-organising enterprises prefer face-to-face communication. Agile Meetings are neither about traditional status reporting or formal presentations, nor serving only individual interests. One-way communication is as undesirable as political games. Rather, it should be a professional exchange about the current results and challenges. The seating order can influence the quality of this exchange as much as the choice of location. Is everyone gathered around a huge conference table? Does each person have their laptop opened up? Is it possible to move around freely? And is the focus really on direct contact, or is it a case of death-by-PowerPoint?

Connecting Mental and Physical Presence: It is no secret that meetings are conducted with more than just our brains. It’s important to engage as many senses as possible. This can happen in many ways: simply standing at the Standups, wandering through gallery-type presentations, using the so-called Law of Two Feet for decision-making or designing workshops for customers who put their hands directly on prototypes. A spectacular example of such activities is the stairwell meeting held by the Richards Group. Information that is relevant for all employees is conveyed as soon as possible in the stairwell that connects the two floors of the company building—thus building a bridge between the different areas, symbolically guarding against compartmental thinking.

Facilitation: In self-organising enterprises, facilitation is rarely done by specialists. According to the idea of encouraging leadership at all levels, facilitation is spontaneously taken over by a meeting participant or determined upfront on a rotating basis. The latter is based on the principle of distributed responsibility, which is especially meaningful at a cross-system level. This principle helps arrange the meetings in a variety of ways and cultivates a broad range of leadership impulses.

Professionalism: Leading effective meetings at the system level is not child’s play. Whether it is coordinating various delegates, seeking stakeholder agreements or designing customer events, many factors for a successful meeting are defined in the preparation phase: setting goals, choosing participants, organising the communication process, as well as documenting and reviewing the results.

3.2 Metrics

The second feedback loop that is used as a standard in self-organising environments is metrics. It’s common knowledge that in traditional organisations much is measured but little is learned. The majority of companies are characterized by figures that sustain the illusion that complex systems can be easily controlled: from company-wide budget planning to department specific cost efficiency and individual performance indicators. This illusion is the reason why many agile practitioners are sceptic of metrics. Most agile practitioners have worked in traditional environments and had bad experiences with metrics. “Why should we measure?”, is how a senior developer at a mid-sized IT service company once made the point: “We know when we deliver good work. Management should trust us instead of wasting our time with pointless indicators.” Although I can understand such concerns, it’s a little like throwing the metrics baby out with the command-and-control bathwater. Because true learning is hard to achieve without measuring what we actually accomplish. How do we determine if we have done a good job? If we have made the best use of our capabilities? Whether we actually improve if we change our way of working? And if the product we ultimately deliver to the customer has the expected value? Which leads us to the big question of what we want to measure and how we do this. Dan Vacanti recommends a lean set of metrics for this purpose.[1] In his view, three metrics are enough to inspect and adapt the quality of our workflow:

- Work in Progress is the number of parallel work items that are being worked on at the same time in any particular activity of our value stream.

- Cycle Time is the time each work item needs to flow through our system to reach the customer.

- Throughput is the amount of work we complete in a given amount of time.

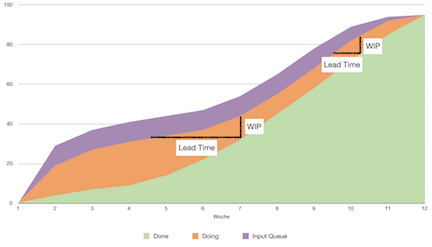

In Actionable Agile Metrics for Predictability Vacanti shows us how we can use a single tool to collect all three measurements: The Cumulative Flow Diagram (CFD). What exactly is a CFD? Basically, a CFD gives us information about the amount of work in our workflow. It shows us how much we have in the Option Pool, how much we are working on and how much is completed over time. Beyond that, we can capture how much work is in which stage of activity, such as idea generation, development or validation. Regardless which degree of detail we are interested in, a CFD is always produced in the same way: a timestamp is assigned to every work item (ticket) as soon as it enters the next activity of our value stream.

Figure 3-2 shows a sample CFD, which allows us to see several things at one glance:

- The proportion between pending work (see Input), work that we are currently working on (see Doing) and completed work (Done).

- The respective WIP limit, meaning the number of all work items that are found in our work system at a given time (vertical line between input and done).

- The average cycle time of work from the chosen starting point in our workflow (the initial point at the very left of the horizontal line within the Doing band) up to the time of completion (the very right of the same horizontal line).

- The average throughput, which is ascertained from the slope of the lower line of the Doing band.

A CFD gives us insight about the quality of our workflow as well as how it develops over time. For example, we can follow the relationship between started and completed work by simply checking if the lines between Input-Doing and Doing-Done have a similar slope, or if the lower line flattens out. If the latter is the case, we know we are finishing less work than we are starting — resulting in a bottleneck, which can eventually lead to a complete standstill.

There are, of course, other metrics for assessing our agile fitness. For example, Histograms are a type of bar chart showing clusters of average cycle times. Another example is a scatter plot, which gives a spatial illustration of the real cycle time per work item. Or even flow efficiency, which shows the relationship between the average cycle time and the actual amount of time that was actively spent working on specific work items. Together with the CFD, such metrics help us to establish Service Level Agreements that we can — assuming a stable, WIP-limited work system — adhere to with a high degree of probability. When we implement a smart control system, we basically know how long, on average, we spent a specific piece of work. Our commitments are no longer based on rough estimates, but on objective performance markers. This way, we can make agreements with our customers and fulfil the expectations associated with those agreements, without overloading our system. Other tools that can strengthen our predictability and reliability are classes of service, which groups work according to risk and prevents unnecessary cost of delay, as well as forecasts that enable future prognosis based on historical data.[3]

3.3 Control

Why are feedback loops so important for agility? The way I see it, there are four obvious answers: