II Opinionated JPA

To use ORM/JPA really well you need to know a lot about it, about the provider, its settings, about caching mechanisms and so on. And you should not be oblivious to SQL either. I’ve never worked on a system where ORM/JPA was used and at the same time everybody was really happy with the result. The system got slower, DBAs asked why we produce crappy SQLs and so on. We fought with ORM drawbacks before we could benefit from the features. It all comes down to inherent complexity of ORM. Any pro can instantly blame us for “just not knowing”… but I think the problem goes deeper.

While I too complain about programmers’ laziness to learn more about the technologies they work with, JPA (plus the provider, mind you!) is a really complex topic. I’ve been studying it for years already. Sure, there was no 100% study time like when you prepare for a certification. On the other hand, most of my study was based on experiences – and not only reactive (solutions to imminent problems) but also proactive (how to do it better on any level, as a coder, designer, architect, whatever).

I always welcome to learn more about JPA. Not because it’s my favourite technology, I just happened to spend so much time with it. When we started one recent project we discussed what to use, I was quite fresh to the team and somehow got convinced to use JPA although I would rather risk Querydsl over SQL directly. But I didn’t mind that much, JPA was quite well known to me. Little I knew how many surprises it would still have for me! The biggest of them all was probably the reason why I started to complain about the JPA on my blog and, eventually, I decided to put my twisted ideas how to utilize JPA into this book.

Generally I don’t like ideas like “let’s just use subset of this”. I don’t believe that hiring dumb Java programmers and forbidding them to use latest Java 8 features is the solution. I rarely saw such a “subset” programmer to write clean code – or they were bright enough to dislike such an arrangement and typically left soon for something better. But the JPA is not a programming language, you’re working with an API and you may choose the patterns you want to use and others you don’t. This time I decided “let’s use SQL more” and “let’s not load graph of objects (even if cached) when I just want to update this single one”. And that’s how it all started – the more I know about JPA the less of it I use. But it still has benefits I don’t want to let go.

So the question is: Can we tune the JPA down without crippling it – or ourselves?

6. Tuning ORM down

Full-blown object-relational mapping maps database foreign keys as relations between objects.

Instead of Integer breedId you have Breed breed where mapping information provides all the

necessary low-level information about the foreign key. This mapping information can be stored

elsewhere (typically XML mapping file) or as annotations directly on the entity (probably more

popular nowadays). Relations can be mapped in any direction, even in reverse, for one or both

directions and in any cardinality with annotations @OneOnOne, @OneToMany, @ManyToOne

and @ManyToMany. If you map both directions you choose the owner’s side, which is kinda more

“in control” of the relationship. Mapping foreign keys as relations is probably the most

pronounced feature of ORM – and originally I wanted to make a case against it in this very book.

In an ironic twist I discovered that the way we bent JPA 2.1 works only on its reference implementation, that is EclipseLink1, this all more than a year too late. I was considering to stop any further work on the book after loosing this most important showcase point. After all I decided to go on with a weaker version after all. We will describe the troubles with to-one relations, their possible solutions – including the one that is not JPA compliant – and there are also other helpful tips, many Querydsl examples throughout and two Querydsl dedicated chapters.

Most of the points I’m going to explain somehow revolve around two rules:

- Be explicit. For instance don’t leave persistence context (session) open after you leave the service layer and don’t wait for the presentation layer to load something lazily. Make explicit contract and fetch eagerly what you need for presentation, just like you would with plain SQL (but still avoiding ORM syndrome “load the whole DB”). Also, don’t rely on caches blindly.

-

Don’t go lazy. Or at least not easily. This obviously stems from the previous point, but

goes further. Lazy may save some queries here and there, but in practice we rely on it too much.

In most cases we can be explicit, but we’re lazy to be so (so let’s not go lazy ourselves either).

There are places where

FetchType.LAZYmeans nothing to JPA. Oh, they will say it’s a hint for a provider, but it’s not guaranteed. That’s nothing for me. Let’s face it – any to-one mapping is eager, unless you add some complexity to your system to make it lazy. It’s not lazy because you annotate it so, deal with it.

As a kind of shortcut I have to mention that Hibernate 5.x supports LAZY to-one relationships

as you’d expect, more about it later in part on how lazy is (not) guaranteed.

When talking about often vain LAZY on to-one, let me be clear that it is still preferred

fetching for collections – and quite reliable for them as well. This does not mean you should

rely on these lazy to-many relations when you want to fetch them for multiple entities at once.

For instance if you want to display a page with the list of messages with attachments, possibly

multiple of them for each message, you should not wait for lazy fetch. More about this in the

chapter Avoid N+1 select.

Price for relations

For me the biggest problem is that JPA does not provide any convenient way how to stop cascading

loads for @ManyToOne and @OneToOne (commonly named to-one in this book as you probably

noticed) relationships. I don’t mind to-many relations, they have their twists, but at least

their lazy works. But to-one typically triggers find by id. If you have a Dog that has an

owner (type Person) and is of specific Breed you must load these two things along with a dog.

Maybe they will be joined by the JPA provider, maybe not2, maybe

they are already in second-level cache and will be “loaded” nearly “for free”. All these options

should be seriously considered, analyzed and proved before you can say that you know what is going

on in your application.

And it just starts there, because Person has an Address which – in case of a rich system –

may further point to District, County, State and so on. Once I wanted to change something

like Currency in a treasury system. It loaded around 50 objects – all of them across these

to-one relations. This may happen when you naively want to change a single attribute in that

currency. In SQL terms, that’s an update of a single column for a single row.

When you insert or update a Dog you can use em.getReference(clazz, id) to get a Breed object

containing only id of the breed. This effectively works as a wrapped foreign key (FK). Heck, you

can just new an empty Breed and set its id, you don’t even have to ask em for the reference.

In case of update you will not save much as that Dog is probably managed already anyway. You

can either update managed entity – which means it loaded previous values for all to-one FKs

cascading as far as it needed – or you can try to merge the entity – but this works only if

you overwrite it completely, it’s not usable for update of a single column. Or should you just use

JPQL update and possibly remove all dogs from the second-level cache? How ORM is that?

Why JPA doesn’t provide better fetch control for finds? I want to work with this Dog object now,

I’m not interested in its relations, just wrap those FK values into otherwise empty entity objects

(like references) and let me do my stuff! How I wished I could just map raw FK value instead of

related object… actually, you can, but while you are able to load such related object explicitly

(find by id), you can’t join on a relationship defined so.

If you use EclipseLink you can do it, but that means you can’t switch to other JPA 2.1 providers reliably, not to mention that dropping the mapping is by no means a minor detour from standard path. However the problems with to-one ultimately led me to these extreme measures and I got rid of to-one mappings and never looked back. Because I based my work on reference implementation of JPA 2.1 (EclipseLink) it took me more than a year to discover I diverged from the standard – and even then only because I started to write tests for this book with both major JPA providers.

More about this in the chapter Troubles with to-one relationships. Other points are much less radical compared to this one. Long before I learnt that being explicit and less lazy is definitely better and we will talk about it in other sections.

How does this affect my domain model?

I stated that this book will not be about architecture, but this is the part where we have to tackle it a bit. If we talk about domain model, we probably also talk about domain driven design (DDD) best described in [DDD]. I can’t claim experience with DDD because I never saw it in practice, but it must work for some, reportedly, especially for complex business domains with lots of rules, etc. Reading [PoEAA] it is obvious that there’s a lot of synergy between DDD and ORM. One may even ask whether to use ORM without DDD at all. And I can’t answer that, sorry.

[PoEAA] recommends other patterns for simpler domain problems (Transaction Script, Table Module) with related data source patterns (Table Data Gateway, Row Data Gateway or Active Mapper). There are some newer architectural solutions as well, like Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) or Data, context and interaction (DCI), both of them usable with object-oriented languages, but not necessarily for every problem.

Back to domain, though. One antipattern often mentioned in relation to ORM/JPA is called Anemic domain model. Let’s quote master Martin Fowler a bit again:

I’m not able to slip out of this topic and make object purists happy, but there are many other

styles of programming and the question (far beyond the scope of this book) is whether being purely

OO is the most important thing after all. In most projects I treated my entities like java beans

with just a little low-level logic to it – so it was mostly this “anemic domain model” song. But

entity objects can be perfect data transfer objects

(DTOs) in many situations. It is still far more advanced compared to amorphous rows of a

ResultSet. We have dumb model, but we can utilize it in a domain if we need to.

I even contemplated something like “domain over entity model” solution where entity is as dumb as possible (it still has responsibility for me, it maps to a database table) and I can wrap it with whatever logic I want in a domain object. This even allows me to reverse some dependencies if I wish so – for instance, in a database my order items point to the order using a foreign key, but in my higher model it can be the other way around, invoice can aggregate items that may not even know about an order.

In any case, whatever we do, we can hardly get rid of all the notions of a particular data store we use, because any such “total abstraction” must lead to some mismatch – and that typically leads to complexity and often significant performance penalty as well. The way I go with this book is trying to get as much benefit from using the JPA without incurring too much cost. Maybe I’m not going for the best approach, but I’m trying to avoid the biggest pain points while accepting that I have SQL somewhere down there.

One thing I respect on Fowler et al. is that they try to balance costs/benefits and they neither push ORM always forward nor do they criticize it all the time without offering real alternatives for the complex cases. However, many other smart and experienced people dislike ORM. Listening to “pure haters” does not bring much to a discussion, but some cases are well-argued, offering options and you can sense the deep understanding of the topic.

When to tune down and when not?

I’d say: “Just use it out of the box until it works for you.” There are good reasons not to rely on something we don’t understand but in custom enterprise software there often is no other way. For many systems everything will be OK, but for slightly complicated database/domain models a lot of things can go wrong.

Performance problems

Most typically the performance degrades first. You definitely should start looking at the generated queries. Something can be fixed in the database (typically with indexes), some queries can be rewritten in the application but sometimes you have to adjust the mapping.

With to-one relations you either have ORM with reliable lazy fetch or you have to do tricks described in Troubles with to-one relationships or even change the mapping in a way that is not JPA compliant, as in Removing to-one altogether. There are also still JPA native queries and JDBC underneath – needless to say that all of this introduces new concept into the code and if we mix it too much the complexity is on the rise.

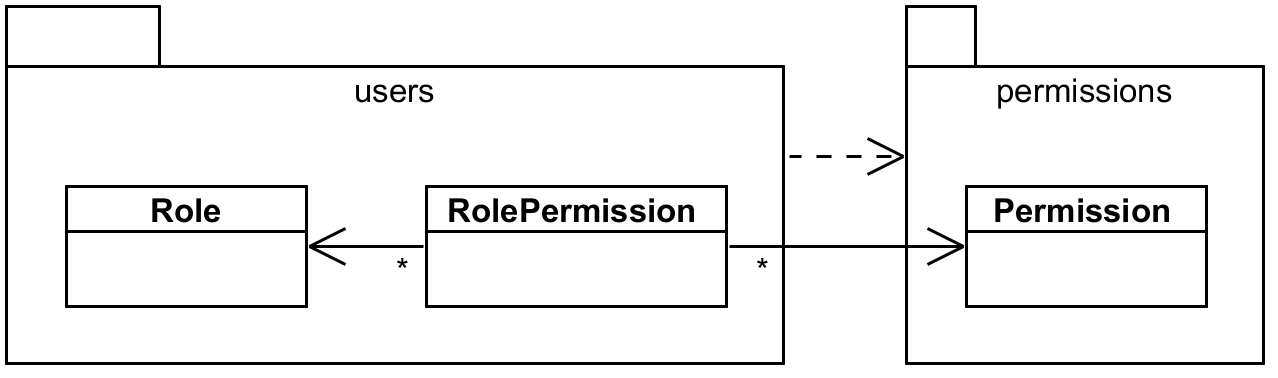

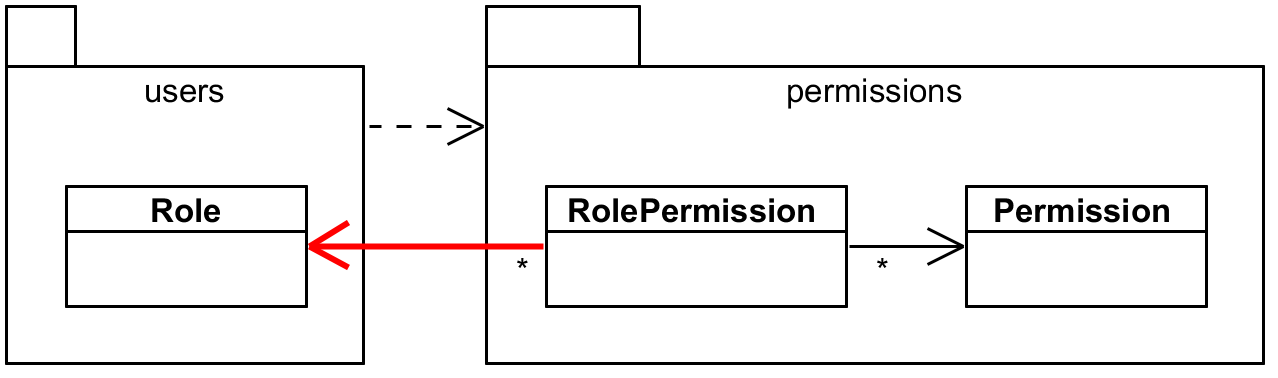

To-many has less problems but some mappers generate more SQL joins than necessary. This can be often mended by introducing explicit entity mapping for the associative table. This does not raise conceptual complexity but some query code may look awkward and more SQL like instead of JPA like. I argue that explicit joins are not that bad though.

Other typical problems involve N+1 select problem, but this type of problems is easy to avoid if we are explicit with our service contracts and don’t let presentation layer to initiate lazy load.

Strange persistence bugs

Most typical enterprise applications can keep persistence context short – and we should. When

ORM got mainstream a lot of people complained about lazy load exceptions (like the Hibernate famous

LazyInitializationException) but this results from misusing ORM. Programmers solved it with

making the session (persistence context) longer and introduced Open Session in View (OSIV)

pattern. This is now widely considered antipattern and there are many good reasons for that.

Using OSIV allowed to keep back-end and front-end programmers separated (with all the disadvantages when two minds do what one mind can do as well), dealing only with some common service API, but this API was leaky when it didn’t load all the data and let presentation fetch the rest on demand. Instead of making it explicit what data the service call provides for the view we let the view3 to perform virtually anything on the managed (“live”) entities. This means that the presentation programmers must be very careful what they do.

There is a serious consequence when the service layer loses control over the persistence context. Transaction boundaries will stop working as one would expect. When the presentation layer combines multiple calls to the service layer you may get unexpected results – results no one have ever consciously implemented.

- Presentation layer first fetches some entity

A. Programmer knows it is read-only call – which is not reliable across the board, but let’s say they know it works for their environment – and because used entity objects as DTO. - Based on the request we are servicing it changes the entity – knowing it will not get persisted in the database.

- There is some transactional read-write service call working with completely different type of

entities

B.

Result without OSIV is quite deterministic and if we hit some lazy-load exception than we should

fetch all the necessary data in the first service call. With OSIV, however, modified A gets

persisted together with changes to B – because they are both part of the same persistence

context which got flushed and committed.

There is a couple of wrong decisions made here. We may argue that even when the presentation layer is not remote we should still service it with one coarse-grained call. Some will scowl at entities used as DTOs and will propose separate DTO classes (others will scowl at that in turn). But OSIV is the real culprit, the one that gives you unexpected behaviour spanning across multiple service calls. Even if the example (real-life one, mind you) seems contrived when we dropped OSIV from our project everything around transactions got much cleaner.

7. No further step without Querydsl

I do realize I’m breaking a flow of the book a little bit, but since I’ve been introduced to this neat library I became a huge fan and I never looked back. It doesn’t affect JPA itself because it sits above it but in your code it virtually replaces both JPQL and especially Criteria API.

To put it simply, Querydsl is a library that – from programmer’s perspective – works like a more expressive and readable version of Java Persistence Criteria API. Internally it first generates JPQL and the rest from there is handled by the JPA provider. Querydsl can actually talk to many more back-ends: SQL, Hibernate directly and others, but we will focus on Querydsl over JPA here. To use it goes in these steps:

- declare the dependency for Querydsl library and to its annotation processor,

- add a step in your build to generate metamodel classes,

- and write queries happily in sort of criteria-like way.

But Criteria API also lets you use generated metamodel, so what’s the deal? Why would I introduce non-standard third-party library when it does not provide any additional advantage? If you even hate this idea, then you probably can stop reading this book – or you can translate all my Querydsl code into JPQL or Criteria yourself, which is perfectly doable, of course! Querydsl does not disrupt the stack under it, it is “just” slapped over the JPA to make it more convenient.

Querydsl brings in a domain-specific language (DSL) in the form of its fluent API. It happens to be so-called internal DSL because it’s still embedded in Java, it’s not different language per se. This fluent API is more concise, readable and convenient than Criteria API.

DSL is a language of some specific domain – in this case it’s a query language very close to JPQL or SQL. It builds on a generated metamodel a lot. API of this metamodel is well-though and takes type-safety to a higher level compared with Criteria API. This not only gives us compile-time checks for our queries, but also offers even better auto-completion in IDEs.

Simple example with Querydsl

Let’s be concrete now – but also very simple. We have a class Dog, each dog has a name

and we will query by this name. Assuming we got hold of EntityManager (variable em) the code

goes like this:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.name.like("Re%"))

5 //.where(QDog.dog.name.startsWith("Re")) // alternative

6 .fetch();

Both where alternatives produce the same result in this case, but startsWith may communicate

the intention better, unless you go for like("%any%") in which case contains would be better.

If you are provided input values for like, leave it. If you can tell from the logic that more

specific name for the operation is better, go for it.

This is a very subtle thing, but we can see that this DSL contains variations that can communicate

our intention more clearly. Criteria API sticks to like only, because that is its internal model.

Other thing is how beautifully the whole query flows. In version 4.x the fluent API got even closer

to JPQL/SQL semantics, it starts with select (what) and ends with fetch which is a mere

signal to deliver the results. As with any other fluent API, you need a terminal operation.

In previous versions you would have no select because it was included in a terminal operation,

e.g. list(QDog.dog). Newer version is one line longer, but closer to the target domain

of query languages. Advanced chapter has a dedicated section on differences between

versions 3 and 4.

Comparison with Criteria API

Both Querydsl and Criteria API are natural fit for dynamic query creation. Doing this with JPQL

is rather painful. Imagine a search form with separate fields for a person

entity, so you can search by name, address, date of birth from–to, etc. We don’t want to add

the search condition when the respective input field is empty. If you have done this before

with any form of query string concatenation then you probably know the pain. In extreme cases

of plain JDBC with prepared statement you even have to write all the ifs twice – first to add

where condition (or and for any next one) and second to set parameters. Technically you can

embed the parameter values into the query, but let’s help the infamous

injection vulnerability get off the top of the

OWASP Top 10 list.

Let’s see how query for our dogs looks like with Criteria API – again starting from em:

1 CriteriaBuilder cb = em.getCriteriaBuilder();

2 CriteriaQuery<Dog> query = cb.createQuery(Dog.class);

3 Root<Dog> dog = query.from(Dog.class);

4 query.select(dog)

5 // this is the only place where we can use metamodel in this example

6 .where(cb.like(dog.get(Dog_.name), "Re%"));

7 // without metamodel it would be:

8 //.where(cb.like(dog.<String>get("name"), "Re%"));

9 List<Dog> dogs = em.createQuery(query)

10 .getResultList();

Let’s observe now:

- First you need to get

CriteriaBuilderfrom existingem. You might “cache” this into a field but it may not play well with EE component model, so I’d rather get it before using. This should not be heavy operation, in most cases entity manager holds this builder already and merely gives it to you (hencegetand notneworcreate). - Then you create an instance of

CriteriaQuery. - From this you need to get a

Rootobject representing content of afromclause. - Then you use the

queryin a nearly-fluent fashion. Version with metamodel is presented with alternative without it in the comment. - Finally, you use

emagain to get aTypedQuerybased on theCriteriaQueryand we ask it for results.

While in case of Criteria API you don’t need to generate metamodel from the entity classes, in Querydsl this is not optional. But using metamodel in Criteria API is advantageous anyway so the need to generate the metamodel for Querydsl using annotation processor can hardly be considered a drawback. It can be easily integrated with Maven or other build as demonstrated in the companion sources to this book or documented on Querydsl site.

For another comparison of Querydsl and Criteria API, you can also check the original blog post from 2010. Querydsl was much younger then (version 1.x) but the difference was striking already.

Comparison with JPQL

Comparing Querydsl with Criteria API was rather easy as they are in the same ballpark. Querydsl, however, with its fluency can be compared to JPQL as well. After all JPQL is non-Java DSL, even though it typically is embedded in Java code. Let’s see JPQL in action first to finish our side-by-side comparisons:

1 List<Dog> dogs = em.createQuery(

2 "select d from Dog d where d.name like :name", Dog.class)

3 .setParameter("name", "Re%")

4 .getResultList();

This is it! Straight to the point, and you can even call it fluent! Probably the best we can do with Querydsl is adding one line to introduce shorter “alias” like this:

1 QDog d = new QDog("d1");

2 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(d)

4 .from(d)

5 .where(d.name.startsWith("Re"))

6 .fetch();

Using aliases is very handy especially for longer and/or more complicated queries. We could

use QDog.dog as the value, or here I introduced new query variable and named it d1. This

name will appear in generated JPQL that looks a little bit different from the JPQL in example

above:

1 select d1 from Dog d1 where d1.name like ?1 escape '!'

There is a subtle difference in how Querydsl generates like clause – which, by the way, is fully

customizable using Querydsl templates. But you can see that alias appears in JPQL, although neither

EclipseLink nor Hibernate bother to translate it to the generated SQL for your convenience.

Now, if we compare both code snippets above (alias creation included) we get a surprising result – there are more characters in the JPQL version! Although it’s just a nit-picking (line/char up or down), it’s clear that Querydsl can express JPQL extremely well (especially in 4.x version) and at the same time it allows for easy dynamic query creation.

You may ask about named queries. Here I admit right away, that Querydsl necessarily introduces overhead (see the next section on disadvantages), but when it comes to query reuse from programmer’s perspective Querydsl offers so called detached queries. While these are not covered in their reference manual (as of March 2016), we will talk more about them in a chapter about advanced Querydsl topics.

What about the cons?

Before we move to other Querydsl topics I’d go over its disadvantages. For one, you’re definitely adding some overhead. I don’t know exactly how big, maybe with the SQL backend (using JDBC directly) it would be more pronounced because ORM itself is big overhead anyway. In any case, there is an object graph of the query in the memory before it is serialized into JPQL – and from there it’s on the same baseline like using JPA directly.

This performance factor obviously is not a big deal for many Querydsl users (some of them are really big names), it mostly does not add too much to the SQL execution itself, but in any case – if you are interested you have to measure it yourself. Also realize that without Querydsl you either have to mess with JPQL strings before you have the complete dynamic WHERE part or you should compare it with Criteria API which does not have to go through JPQL, but also creates some object graph in the memory (richer or not? depends).

Documentation, while good, is definitely not complete. For instance, detached queries are not mentioned in their Querydsl Reference Guide and there is much more you need to find out yourself. You’ll need to find your own best practices, probably, but it is not that difficult with Querydsl. Based (not only) on my own experience, it is literally joy to work with Querydsl and explore what it can provide – for me it worked like this from day zero. It’s also very easy to find responses on the StackOverflow or their mailing-list, very often provided directly by Querydsl developers. This makes any lack of documentation easy to overcome.

Finally, you’re adding another dependency to the project, which may be a problem for some. For the teams I worked with it was well compensated by the code clarity Querydsl gave us.

Be explicit with aliases

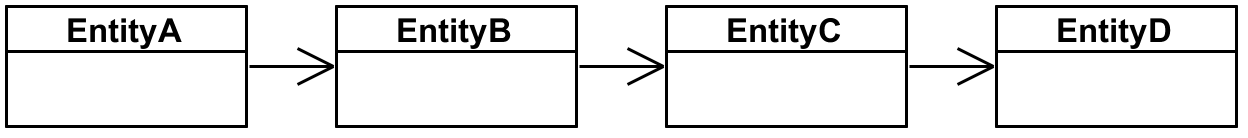

With attribute paths at our disposal it is easy to require some data without explicitly using joins. Let’s consider the following entity chain:

We will start all the following queries at EntityA and first we will want the list of related

EntityC objects. We may approach it like this:

1 List<EntityC> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityA.entityA.entityB.entityC)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .fetch();

This works and Hibernate generates the following SQL:

1 select

2 entityc2_.id as id1_5_,

3 entityc2_.entityD_id as entityD_3_5_,

4 entityc2_.name as name2_5_

5 from

6 EntityA entitya0_,

7 EntityB entityb1_ inner join

8 EntityC entityc2_ on entityb1_.entityC_id=entityc2_.id

9 where entitya0_.entityB_id=entityb1_.id

Effectively these are both inner joins and the result is as expected. But what happens if we

want to traverse to EntityD?

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityA.entityA.entityB.entityC.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .fetch();

After running this we end up with NullPointerException on the line with select method. What

happened? The core problem is that it is not feasible to generate infinitely deep path using

final fields. Querydsl offers some solutions to this as discussed in the reference

documentation.

You can either ask the generator to initialize the path you need with the @QueryInit annotation

or you can mark the entity with @Config(entityAccessors=true) which generates accessor methods

instead of final fields. In the latter case you’d simply use this annotation on EntityC and

in the select call use entityD() which would create the property on the fly. This way you can

traverse relations ad lib. It requires some Querydsl annotations on the entities – which you may

already use, for instance for custom constructors, etc.

However, instead of customizing the generation I’d advocate being explicit with the aliases. If there is a join let it show! We can go around the limitation of max-two-level paths using just a single join:

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityB.entityB.entityC.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .join(QEntityA.entityA.entityB, QEntityB.entityB)

5 .fetch();

Here we lowered the nesting back to two levels by making EntityB explicit. We used existing

default alias QEntityB.entityB. This query makes the code run, but looks… unclean, really.

Let’s go all the way and make all the joins explicit:

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityD.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 // second parameter is alias for the path in the first parameter

5 .join(QEntityA.entityA.entityB, QEntityB.entityB)

6 // first parameter uses alias from the previous line

7 .join(QEntityB.entityB.entityC, QEntityC.entityC)

8 .join(QEntityC.entityC.entityD, QEntityD.entityD)

9 .fetch();

Now this looks long, but it says exactly what it does – no surprises. We may help it in a couple of ways but the easiest one is to introduce the aliases upfront:

1 QEntityA a = new QEntityA("a");

2 QEntityB b = new QEntityB("b");

3 QEntityC c = new QEntityC("c");

4 QEntityD d = new QEntityD("d");

5 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

6 .select(d)

7 .from(a)

8 .join(a.entityB, b)

9 .join(b.entityC, c)

10 .join(c.entityD, d)

11 .fetch();

I like this most – it is couple of lines longer but very clean and the query is very easy to read. Anytime I work with joins I always go for explicit aliases.

Another related problem is joining the same entity more times (but in different roles). Newbie programmers also often fall for a trap of using the same alias – typically the default one offered on each Q-class – for multiple joins on the same entity. There can be two distinct local variables representing these aliases but they both point to the same object instance – hence it’s still the same alias. Whenever I join an entity more times in a query I always go for created aliases. When I’m sure that an entity is in a query just once I may use default alias. It really pays off to have a strict and clean strategy of how to use the aliases and local variables pointing at them.

Functions and operations

Let’s see what data we will work on in the next sections so we can understand the returned results.

| id | name |

|---|---|

| 1 | collie |

| 2 | german shepherd |

| 3 | retriever |

| name | age | breed_id |

|---|---|---|

| Lassie | 7 | 1 (collie) |

| Rex | 6 | 2 (german shepherd) |

| Ben | 4 | 2 (german shepherd) |

| Mixer | 3 |

NULL (unknown breed) |

The following examples can be found on GitHub in FunctionsAndOperations.java.

When we want to write some operation we simply follow the fluent API. You can write QDog.dog.age.

and hit auto-complete – this offers us all the possible operations and functions we can use on the

attribute. These are based on the known type of that attribute, so we only get the list of

functions that make sense (from technical point of view, not necessarily from business perspective,

of course).

This naturally makes sense for binary operations. If we want to see dog’s age halved we can do it like this:

1 List<Tuple> dogsGettingYounger = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.age.divide(2))

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .fetch();

We will cover Tuples soon, now just know they can be printed easily and the

output would be [[Lassie, 3], [Rex, 3], [Ben, 2], [Mixer (unknown breed), 1]]. We are not limited

to constants and can add together two columns or multiply amount by rate, etc. You may also

integer results of the division – this can be mended if you select age as double – like this:

1 // rest is the same

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.age.castToNum(Double.class).divide(2))

Unary functions are less natural as they are appended to the attribute expression just like binary operations – they just don’t take any arguments:

1 List<Tuple> dogsAndNameLengths = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.name.length())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .fetch();

This returns [[Lassie, 6], [Rex, 3], [Ben, 3], [Mixer (unknown breed), 21]]. JPA 2.1 allows

the usage of any function using the FUNCTION construct. We will cover this

later in the advanced chapter on Querydsl.

Aggregate functions

Using aggregate functions is the same like any other function – but as we know from SQL, we need to group by any other non-aggregated columns. For instance to see the counts of dogs for any age we can write:

1 List<Tuple> dogCountByAge = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.age, QDog.dog.count())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .groupBy(QDog.dog.age)

5 .fetch();

Our example data have each dog with different age, so the results are boring.

If we want to see the average age of dogs per breed we use this:

1 List<Tuple> dogAvgAgeByBreed = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.name, QDog.dog.age.avg())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .groupBy(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.name)

6 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

7 .fetch();

Because of leftJoin this returns also line [null, null, 3.0]. With innerJoin (or just join)

we would get only dogs with defined breed. On screen I’m probably interested in breed’s name but

that relies on their uniqueness – which may not be the case. To get the “true” results per breed

I added breed.id into the select clause. We can always display just names and if they are not

unique user will at least be curious about it. But that’s beyond the discussion for now.

Querydsl supports having clause as well if the need arises. We also demonstrated orderBy

clause, just by the way, as it hardly deserves special treatment in this book.

Subqueries

Here we will use the same data like in the previous section on functions and operations. The following examples can be found on GitHub in Subqueries.java). You can also check Querydsl reference documentation.

Independent subquery

If we want to find all the dogs that are of breed with a long name, we can do this:

1 List<Dog> dogsWithLongBreedName = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.breed.in(

5 new JPAQuery<>() // no EM here

6 .select(QBreed.breed)

7 .from(QBreed.breed)

8 // no fetch on subquery

9 .where(QBreed.breed.name.length().goe(10))))

10 .fetch();

This returns Ben and Rex, both german shepherds. Note that subquery looks like normal query, but

we don’t provide EntityManager to it and we don’t use any fetch. If you do the subquery will

be executed on its own first and its results will be fetched into in clause just as any other

collection would. This is not what we want in most cases – especially when the code leads us to

an idea of a subquery. The previous result can be achieved with join as well – and in such cases

joins are almost always preferable.

To make our life easier we can use JPAExpressions.select(...) instead of

new JPAQuery<>().select(...). There is also a neat shortcut for the subquery with select and

from with the same expression.

1 JPAExpressions.selectFrom(QBreed.breed) ...

We will prefer using JPAExpression from now on. Another example finds average age of all dogs

and returns only those above it:

1 List<Dog> dogsOlderThanAverage = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.age.gt(

5 JPAExpressions.select(QDog.dog.age.avg())

6 .from(QDog.dog)))

7 .fetch();

This is perhaps on the edge regarding usage of the same alias QDog.dog for both inner and outer

query, but I dare to say it does not matter here. In both previous examples the same result can be

obtained when we execute the inner query first because it always provides the same result. What if

we need to drive some conditions of the inner query by the outer one?

Correlated subquery

When we use object from the outer query in the subquery it is called correlated subquery. For example, we want to know for what breeds we have no dogs:

1 List<Breed> breedsWithoutDogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(

5 JPAExpressions.selectFrom(QDog.dog)

6 .where(QDog.dog.breed.eq(QBreed.breed))

7 .notExists())

8 .fetch();

We used a subquery with exist/notExists and we could omit select, although it can be used.

This returns a single breed – retriever. Interesting aspect is that the inner query uses

something from the outer select (here QBreed.breed). Compared to the subqueries from the

previous section this one can have different result for each row of the outer query.

This one can actually be done by join, as well, but in this case I’d not recommend it. Depending on

the mapping you use, various things work on various providers. When you have @ManyToOne Breed

breed than this works on EclipseLink:

1 List<Breed> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.eq(QDog.dog.breed))

5 .where(QDog.dog.isNull())

6 // distinct would be needed for isNotNull (breeds with many dogs)

7 // not really necessary for isNull as those lines are unique

8 .distinct()

9 .fetch();

Alas, it fails on Hibernate (5.2.2) with InvalidWithClauseException: with clause can only

reference columns in the driving table. It seems to be an open bug mentioned in this

StackOverflow answer – and the suggested solution

of using plain keys instead of objects indeed work:

1 // the rest is the same

2 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.id.eq(QDog.dog.breedId))

For this we need to switch Breed breed mapping to plain FK mapping, or use both of them with

one marked with updatable false:

1 @Column(name = "breed_id", updatable = false, insertable = false)

2 private Integer breedId;

You may be tempted to avoid this mapping and do explicit equals on keys like this:

1 // the rest is the same

2 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.id.eq(QDog.dog.breed.id))

But this has its own issues. EclipseLink joins the breed twice, second time using implicit join after left join which is a construct that many databases don’t really like (H2 or SQL Server, to name just those where I noticed this quite often) and it fails on JDBC/SQL level. Hibernate also generates the superfluous join to the breed but at least orders them more safely. Still, if you use EclipseLink simply don’t add explicit IDs to your paths and if you’re using Hibernate at least know it’s not efficient join-wise and also is not really portable across JPA providers.

There is another JPA query that works and also arguably reads most naturally:

1 List<Breed> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.dogs.isEmpty())

5 .fetch();

Internally this generates subquery with count or (not) exists anyway, there is no way around it.

But for this to work we also have to add the mapping to Breed which was not necessary for the

previous non-JPA joins:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed")

2 private Set<Dog> dogs;

This mapping may be rather superfluous for some cases (why should breed know the list of dogs?) but it should not hurt.

We somehow foreshadowed themes from the following chapters on various mapping problems but we’re not done with subqueries (or Querydsl) just yet. Let’s now try to find dogs that are older than average – but this time for each breed:

1 QDog innerDog = new QDog("innerDog");

2 List<Dog> dogsOlderThanBreedAverage = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(QDog.dog)

4 .from(QDog.dog)

5 .where(QDog.dog.age.gt(

6 JPAExpressions.select(innerDog.age.avg())

7 .from(innerDog)

8 .where(innerDog.breed.eq(QDog.dog.breed))))

9 .fetch();

Notice the use of innerDog alias which is very important. Had you used QDog.dog in the subquery

it would have returned the same results like dogsOlderThanAverage above. This query returns only

Rex, because only german shepherds have more than a single dog – and a single (or no) dog can’t be

older than average.

This section is not about going deep into subquery theory (I’m not the right person for it in the

first place), but to demonstrate how easy and readable it is to write subqueries with Querydsl

API. We’re still limited by JPQL, that means no subqueries in from or select clauses). When

writing subqueries be careful not to “reuse” alias from the outer query.

Pagination

Very often we need to cut our results into smaller chunks, typically pages for some user interface,

but pagination is often used also with various APIs. To do it manually, we can simply specify

offset (what record is the first) and limit (how many records):

1 List<Breed> breedsPageX = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17)) // random where

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

6 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

7 .limit(pageSize)

8 .fetch();

I used variables page (starting at one, hence the correction) and pageSize to calculate the

right values. Any time you paginate the results you want to use orderBy because SQL specification

does not guarantee any order without it. Sure, databases typically give you results in some natural

order (like “by ID”), but it is dangerous to rely on it.

Content of the page is good, but often we want to know total count of all the results. We use the

same query with the same conditions, we just first use .fetchCount like this:

1 JPAQuery<Breed> breedQuery = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17))

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc());

6

7 long total = breedQuery.fetchCount();

8 List<Breed> breedsPageX = breedQuery

9 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

10 .limit(pageSize)

11 .fetch();

We can even add if skipping the second query when count is 0 as we can just create an empty list.

And because this scenario is so typical Querydsl provides a shortcut for it:

fetchResults 1 QueryResults<Breed> results = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17))

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

6 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

7 .limit(pageSize)

8 .fetchResults();

9 System.out.println("total count: " + results.getTotal());

10 System.out.println("results = " + results.getResults());

QueryResults wrap all the information we need for paginated result, including offset and limit.

It does not help us with reverse calculation of the page number from an offset, but I guess we

probably track the page number in some filter object anyway as we needed it as the input in the

first place.

And yes, it does not execute the second query when the count is zero.4

Tuple results

When you call fetch() the List is returned. When you call fetchOne() or fetchFirst() one

object is returned. The question is – what type of object? This depends on the select clause

which can have a single parameter which determines the type or you can use list of expressions

for select in which case Tuple is returned. That is, a query with select(QDog.dog) will

return Dog (or List<Dog>) because QDog.dog is of type QDog that extends

EntityPathBase<Dog> which eventually implements Expression<Dog> – hence the Dog.

But when you return multiple results we need to wrap them somehow. In JPA you will get Object[]

(array of objects) for each row. That works, but is not very convenient. Criteria API brings

Tuple for that reason which is much better. Querydsl uses Tuple idea as well. What’s the deal?

1 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QBreed.breed.name)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .join(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .fetch();

6 result.forEach(t -> {

7 String name = t.get(QDog.dog.name);

8 String breed = t.get(1, String.class);

9 System.out.println("Dog: " + name + " is " + breed);

10 });

As you can see in the forEach block we can extract columns by either using the expression that

was used in the select as well (here QDog.dog.name) or by index. Needless to say that the first

way is preferred. You can also extract the underlying array of objects using toArray().

Because Tuple works with any expression we can use the whole entities too:

1 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog, QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .join(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .fetch();

6 result.forEach(t -> {

7 Dog dog = t.get(QDog.dog);

8 Breed breed = t.get(QBreed.breed);

9 System.out.println("\nDog: " + dog);

10 System.out.println("Breed: " + breed);

11 });

And of course, you can combine entities with columns ad-lib.

There are other ways how to combine multiple expressions into one object. See the reference guide to see how to populate beans, or how to use projection constructors.

Fetching to-many eagerly

In the following example we select all the breeds and we want to print the collection of the dogs of that breed:

1 // mapping on Breed

2 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed")

3 private Set<Dog> dogs;

4

5 // query

6 List<Breed> breed = new JPAQuery<>(em)

7 .select(QBreed.breed)

8 .from(QBreed.breed)

9 .fetch();

10 breed.forEach(b ->

11 System.out.println(b.toString() + ": " + b.getDogs()));

This executes three queries. First the one that is obvious and then one for each breed when you

want to print the dogs. Actually, for EclipseLink it does not produce the other queries and merely

prints {IndirectSet: not instantiated} instead of the collection content. You can nudge

EclipseLink with something like b.getDogs().size() or other meaningful collection operation.

It seems toString() isn’t meaningful enough for EclipseLink.

We can force the eager fetch when we adjust the mapping:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed", fetch = FetchType.EAGER)

2 private Set<Dog> dogs;

However, while the fetch is eager, EclipseLink still does it with three queries (1+N in general).

Hibernate uses one query with join. So yes, it is eager, but not necessarily efficient. There is

a potential problem with paging when using join to to-many – the problem we mentioned

already and we’ll return to it later. What happens when

we add offset and limit?

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .offset(1)

5 .limit(1)

6 .fetch();

Because EclipseLink uses separate query for breeds, nothing changes and we get the second result (by the way, we forgot to order it!). Hibernate is smart enough to use separate query too, as soon as it smells the offset/limit combo. It makes sense, because query says “gimme breeds!” – although not everything in JPA is always free of surprises. In any case, eager collection is not recommended. There may be notable exceptions – maybe some embeddables or other really primitive collections – but I’d never risk fetching collection of another entities as it asks for fetching the whole database eventually.

What if we write a query that joins breed and dogs ourselves? We assuming no pagination again.

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .join(QBreed.breed.dogs, QDog.dog)

5 .distinct()

6 .fetch();

7 breeds.forEach(b ->

8 System.out.println(b.toString() + ": " + b.getDogs()));

If you check the logs queries are indeed generated with joins, but it is not enough. EclipseLink

still prints uninitialized indirect list (and relevant operation would trigger the select),

Hibernate prints it nicely, but needs additional N selects as well. We need to say what collection

we want initialized explicitly using fetchJoin like so:

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .join(QBreed.breed.dogs).fetchJoin()

5 .distinct()

6 .fetch();

You use fetchJoin() just after the join with a collection path and in this case you don’t

need to use second parameter with alias, unless you want to use it in where or select, etc.5

Because we used join with to-many relations ourselves JPA assumes we want all the results

(5 with our demo data defined previously). That’s why we also added

distinct() – this ensures we get only unique results from the select clause. But these unique

results will still have their collections initialized because SQL still returns 5 results and

JPA “distincts” it in post-process. This means we cannot paginate queries with joins, distinct

or not. This is something we will tackle in a dedicated section.

Querydsl and code style

Querydsl is a nice API and DSL but may lead to horrific monsters like:

1 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction

3 .clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.transactionId))

4 .from(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement)

5 .join(QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount).on(

6 QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementId

7 .eq(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement.id))

8 .join(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction)

9 .on(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.

10 clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountId

11 .eq(QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount.id))

12 .where(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

13 .fetch();

The problems here are caused by long entity class names but often there is nothing you can do about

it. Querydsl exacerbates it with the duplication of the name in QClassName.className. There are

many ways how to tackle the problem.

We can introduce local variables, even with very short names as they are very close to the

query itself. In most queries I saw usage of acronym aliases, like cabat for

QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction. This clears up the query significantly, especially when

the same alias is repeated many times:

1 QClientAgreement ca = QClientAgreement.clientAgreement;

2 QClientAgreementBankAccount caba =

3 QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount;

4 QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction cabat =

5 QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction;

6 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

7 .select(cabat.transactionId)

8 .from(ca)

9 .join(caba).on(caba.clientAgreementId.eq(ca.id))

10 .join(cabat).on(cabat.clientAgreementBankAccountId.eq(caba.id))

11 .where(ca.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

12 .fetch();

You give up some explicitness in the query with those acronyms but you get much higher signal-to-noise ratio which can easily overweight the burden of mental mapping to local variables.

Another option is to use static imports which halves the QNames into half:

1 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.transactionId)

3 .from(clientAgreement)

4 .join(clientAgreementBankAccount).on(

5 clientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementId.eq(clientAgreement.id))

6 .join(clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction).on(

7 clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountId

8 .eq(clientAgreementBankAccount.id))

9 .where(clientAgreement.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

10 .fetch()

This is clearly somewhere between the first (totally unacceptable) version and the second where

the query was very brief at the cost of using acronyms for aliases. Using static names is great

when they don’t collide with anything else. But while QDog itself says clearly it is metadata

type, name of its static field dog clearly collides with any dog variable of a real Dog type

you may have in your code. Still, we use static imports extensively in various infrastructural

code where no confusion is possible.

We also often use field or variable named $ that represents the root of our query. I never ever

use that name for anything else and long-term experiments showed that it brought no confusion into

our team whatsoever. Snippet of our DAO class may look like this:

1 public class ClientDao {

2 public static final QClient $ = QClient.client;

3

4 public Client findByName(String name) {

5 return queryFrom($) // our shortcut for new/select/from

6 .where($.name.eq(name))

7 .fetchOne($);

8 }

9

10 public List<Client> listByRole(ClientRole clientRole) {

11 return queryFrom($)

12 .where($.roles.any().eq(clientRole))

13 .list($);

14 }

15 ...

As a bonus you can see how any() is used on collection path $.roles. You can even go on

to a specific property – for instance with our demo data we can obtain list of breeds where any

dog is named Rex like this:

1 List<Breed> breedsWithRex = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.dogs.any().name.eq("Rex"))

5 .fetch();

This produces SQL with EXISTS subquery although the same can be written with join

and distinct.

More

That’s it for our first tour around Querydsl. We will see more in the chapter on more advanced features (or perhaps just features used less). In the course of this chapter there was plenty of links to other resources too – let’s sum it up:

- Querydsl Reference Guide is the first stop when you want to learn more. It is not the last stop though, as it does not even cover all the stuff from this chapter. It still is a useful piece of documentation.

- Querydsl is also popular enough on StackOverflow with Timo Westkämper himself often answering the questions.

- Finally there is their mailing-list

(

querydsl@googlegroups.com) – with daily activity where you get what you need.

For an introduction you can also check this slide deck that covers older version 3, but except for the fluent API changes the concept is the same.

8. Troubles with to-one relationships

Now we can get back to the topics I foreshadowed in the introduction to this opinionated part.

We will show an example of @ManyToOne mapping and we will analyze our options how to load

an entity with such a relationship when we are not interested in its target relation.

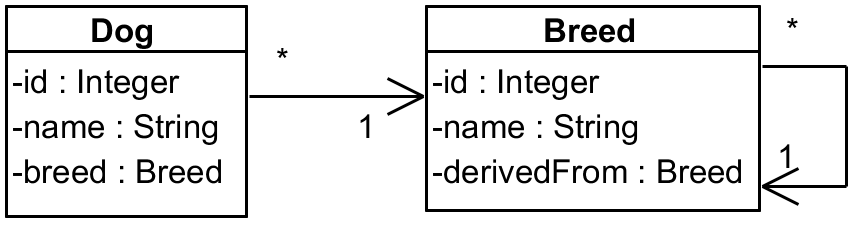

Simple example of @ManyToOne

We will continue experimenting on dogs in the demonstration of to-one mapping. The code is

available in a GitHub sub-project many-to-one-eager.

This particular demo project is also referenced in appendix Project example

where particulars of build files and persistence.xml are described. We will skip these but

because this is our first serious experiment in the book we will still include more of the code

listing to establish kind of a baseline.

Our model is simple, but there is a twist to it. We have a Dog and Breed entities where a Dog

points to its Breed – and to make things just a little bit tricky the Breed is a hierarchy

where each Breed points to its parent via attribute called derivedFrom.

Our entities are quite plain – Dog looks like this:

1 package modeltoone;

2

3 import javax.persistence.*;

4

5 @Entity

6 public class Dog {

7

8 @Id

9 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

10 private Integer id;

11

12 private String name;

13

14 @ManyToOne

15 private Breed breed;

The rest are getters/setters – complete code is here.

Referenced Breed is mapped like this (full source code):

1 package modeltoone;

2

3 import javax.persistence.*;

4

5 @Entity

6 public class Breed {

7

8 @Id

9 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

10 private Integer id;

11

12 private String name;

13

14 @ManyToOne

15 private Breed derivedFrom;

There is nothing special on these entities, but let’s see what happens when we load some dog. In the process we will also compare Hibernate and EclipseLink, that’s why we have two nearly equivalent persistence units in our persistence.xml. We will prepare data like this:

1 EntityManagerFactory emf = Persistence

2 .createEntityManagerFactory(persistenceUnitName);

3 try {

4 EntityManager em = emf.createEntityManager();

5 em.getTransaction().begin();

6

7 Breed wolf = new Breed();

8 wolf.setName("wolf");

9 em.persist(wolf);

10

11 Breed germanShepherd = new Breed();

12 germanShepherd.setName("german shepherd");

13 germanShepherd.setDerivedFrom(wolf);

14 em.persist(germanShepherd);

15

16 Breed collie = new Breed();

17 collie.setName("collie");

18 collie.setDerivedFrom(germanShepherd);

19 em.persist(collie);

20

21 Dog lassie = new Dog();

22 lassie.setName("Lassie");

23 lassie.setBreed(collie);

24 em.persist(lassie);

25

26 em.getTransaction().commit();

27 em.clear();

28 emf.getCache().evictAll();

29

30 // here comes "demo" code

31 } finally {

32 emf.close();

33 }

Sorry for copy/pasting, eventually the breed and dog creation would end up in separate methods, but for our demo this code will do. Also the breed tree is probably far from reality, but that’s not the point. Let’s say that collie was bred from shepherd which descends from wolf.

Notice the clearing of the entity manager, alternatively we could close and reopen one. Another thing is we are clearing up the second-level cache as well. We may argue what the real case is, but unless you have all your entities cached all the time an empty cache simulates real-life scenario. And we’re just finding the dog by its ID – we know it’s 1:

1 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

What happens at this line? Let’s see the console for Hibernate (manually wrapped):

1 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

2 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_, breed1_.id as id1_0_1_, breed1_.derivedFrom_id

3 as derivedF3_0_1_, breed1_.name as name2_0_1_, breed2_.id as id1_0_2_,

4 breed2_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_2_, breed2_.name as name2_0_2_

5 from Dog dog0_

6 left outer join Breed breed1_ on dog0_.breed_id=breed1_.id

7 left outer join Breed breed2_ on breed1_.derivedFrom_id=breed2_.id

8 where dog0_.id=?

9 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as

10 derivedF3_0_0_, breed0_.name as name2_0_0_, breed1_.id as id1_0_1_,

11 breed1_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_1_, breed1_.name as name2_0_1_

12 from Breed breed0_

13 left outer join Breed breed1_ on breed0_.derivedFrom_id=breed1_.id

14 where breed0_.id=?

Two selects that load a dog and all three breeds – not that bad. If you know traverse up the breed tree, there would be no more select. On the other hand, if you cared about the actual breed of this dog and not about what this breed is derived from we fetched those unnecessarily. There is no way to tell the JPA that dummy breed with shepherd’s ID would do on the collie entity and that you don’t want this to-one relationship fetching to propagate any further.

Let’s look at EclipseLink now:

1 SELECT ID, NAME, BREED_ID FROM DOG WHERE (ID = ?)

2 bind => [1]

3 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

4 bind => [3]

5 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

6 bind => [2]

7 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

8 bind => [1]

This is as obvious as it gets. Each entity is loaded with a separate query. Effect is the same like with Hibernate, EclipseLink just needs more round-trips to the database. Personally I don’t care how many selects it takes in the end as this is part of the JPA provider strategy. We are not going to fine-tune Hibernate or EclipseLink. We’re going to cut off this loading chain.

How about going lazy?

Let’s be a bit naive (I was!) and mark the relationships as lazy:

1 @ManyToOne(fetch = FetchType.LAZY)

2 private Breed breed;

And the same for Breed.derivedFrom. Our testing code is like this:

1 System.out.println("\nfind");

2 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

3 System.out.println("\ntraversing");

4 Breed breed = dog.getBreed();

5 while (breed.getDerivedFrom() != null) {

6 breed = breed.getDerivedFrom();

7 }

8 System.out.println("breed = " + breed.getName());

This way we should see what selects are executed when. Hibernate out of the box works as expected:

1 find

2 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

3 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_ from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

4

5 traversing

6 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

7 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

8 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

9 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

10 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

11 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

12 breed = wolf

Selects are executed as needed (lazily). For long-term Hibernate users this often gives an impression that it should work like this. Let’s migrate to EclipseLink then:

1 find

2 SELECT ID, NAME, BREED_ID FROM DOG WHERE (ID = ?)

3 bind => [1]

4 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

5 bind => [3]

6 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

7 bind => [2]

8 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

9 bind => [1]

10

11 traversing

12 breed = wolf

Just like before EclipseLink generates four selects and executes them right away when you find the entity. How is this possible? Firstly, from the [JPspec] perspective (section 2.2):

Footnote [4] is important here, obviously. So “it should” but it’s just “a hint”.

These results can be recreated by running SingleEntityReadLazy (in test classpath) from GitHub sub-project

many-to-one-lazy.

How bulletproof is Hibernate’s solution?

Pretty much bulletproof, I have to say. As presented here, we annotated fields, which means we

implied Access(FIELD). Hibernate can’t get away with just intercepting getters/setters, it has

to do better. Let’s try a bit of reflection:

1 System.out.println("\nfind");

2 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

3 System.out.println("\nhacking");

4 Field breedField = dog.getClass().getDeclaredField("breed");

5 System.out.println(breedField.getType());

6 breedField.setAccessible(true);

7 Object val = breedField.get(dog);

8 System.out.println("val = " + val);

And now the console output mixed with logs:

1 find

2 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

3 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_ from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

4

5 hacking

6 class modeltoone.Breed

7 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

8 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

9 val = Breed{id=3, name='collie'}

This is perfectly lazy. The solution seems even magic when you think about it.

Lazy to-one not guaranteed

Doing lazy collection (@OneToMany or @ManyToMany) is not a problem,

we would probably mess around a bit but eventually we would create some collection implementation

that does it right. The trick is we have the actual entities wrapped in a collection that works

as an intermediary. We don’t need to perform any bytecode voodoo on the entity class.

With to-one situation changes dramatically as you have no intermediary. It would be interesting if JPA at least offered some wrapper to enforce lazy behaviour when you really need it regardless of the JPA provider, but that would give away you’re using some ORM (like you don’t know) and even more voices would talk about that “leaking abstraction”.

While my tests with Hibernate looked great, the results are not portable across JPA providers as we saw. Also, I’d not bet that you’ll get the same results because there’s still a lot of questions how to make Hibernate lazy for to-one relationships, many of them quite new.

So the whole trouble with to-one is that you rely on out-of-language features (bytecode

manipulation) for LAZY support or suffer potentially very costly cascade of relation loading.

The cost may be alleviated by a cache somewhat, but you just trade CPU/network cost for memory

(and CPU for GC, mind you) – even if you don’t need most of the loaded data at all (maybe ever).

Also, LAZY can work perfectly for WAR application in Java EE container but it may suddenly stop

working when switching to embedded container. I’m not saying that LAZY is not worth the trouble,

on the contrary, I believe that lazy relationship is essential for both to-many (as default) and

to-one (in most circumstances) but it indeed can be a lot of trouble during the build time or

runtime, especially in Java SE environment. Java EE with its default provider may be nice to us,

but it still isn’t guaranteed.

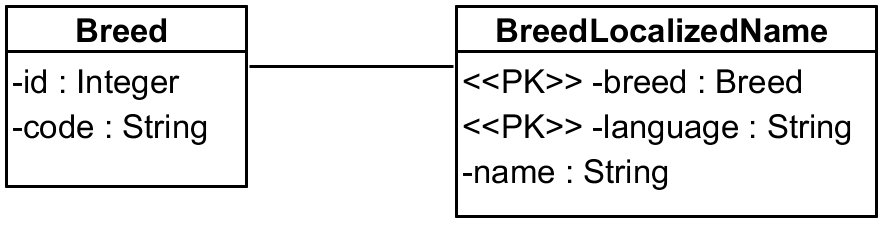

Dual relationship mapping

When I say dual mapping I mean mapping of the relationship both as an object and foreign key value. It looks like this:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3 ...

4 @ManyToOne

5 @JoinColumn(name = "breed_id", updatable = false, insertable = false)

6 private Breed breed;

7

8 @Column(name = "breed_id")

9 private Integer breedId;

I can’t find example of this anywhere in the [JPspec], neither can I find anything

that would forbid it (although I’m not really sure) – but it works in both major JPA providers.

The key is marking one of these attributes as readonly, that’s what updatable/insertable=false

does. The other mapping is primary – the one used for updates. I prefer when the raw foreign key

is primary because now I don’t need any Breed object for update when I have its ID already (it’s

easy to extract ID from the object if I have it too). Getters are returning values for respective

fields, setters are designed in such a way that the persisted field (here foreign key value) is

always updated:

1 public Breed getBreed() {

2 return breed;

3 }

4

5 public void setBreed(Breed breed) {

6 this.breed = breed;

7 breedId = breed.getId();

8 }

9

10 public Integer getBreedId() {

11 return breedId;

12 }

13

14 public void setBreedId(Integer breedId) {

15 this.breedId = breedId;

16 }

In this case it means merely setting the breedId field when breed is updated. We don’t care

about breed in the other setter. Programmer has to know that foreign key value is primary

breed attribute here and act accordingly. For instance, this setup is not transparent when

persisting new entities. If we persist a fresh breed there is no guarantee its ID is already

available as autoincrement fields are filled in after the actual INSERT is flushed to the

database. With EclipseLink we have to force it if we need the ID – calling setBreed(newBreed)

would otherwise set dog’s FK to the breed to null. Hibernate is rather eager with INSERTs which

is convenient for this scenario.

The reverse case – with breed as the persisted field and breedId as the readonly one – is less

useful and I cannot find any reasons to use it instead of the traditional JPA relationship mapping.

You can get foreign key value anytime calling breed.getId().

In any case, there are no “savings” during the load phase, but we can store new entities with

raw foreign key values if we have those (and for whatever reason don’t have the entities loaded).

Previously we mentioned the possibility of using entities as wrappers for the foreign keys, but we

also showed that it doesn’t play well with cascade = PERSIST.

If we go back to dreaming – imagine we could request em.find for a dog by ID with a hint not

to load readonly mappings (or otherwise designated). This would save us the hassle during the

loading phase as well and made the whole read-update scenario (part of typical CRUD) based on

foreign key values with the opportunity to load the relationships – if we wished so. Any of this

could be specified on the entity level based on typical patterns of usage. Imagine all the people

/ fetching like they want. Oh-oh… (Lennon/Richter)

Dual mapping like this has one big advantage compared to the pure foreign key mapping – with

the breed mapping we can construct JPA compliant JPQL queries without waiting for the next

version of JPA – if they bring the option of joining root entities at all, that is. But currently

dual mapping also means that we can only avoid the fetch cascade if we:

- Rely on

LAZYhint – not guaranteed by JPA, but if provided by a provider, you can consider it solved. - Or we query the entity with all the columns named explicitly (e.g. include

breedId, but skipbreed) – this, however, cripples the caching (if you use it), you don’t get attached entity and (above all) it is annoying to code. We will talk more about this in the following sections.

So, dual mapping is an interesting tool but does not allow us to avoid all the eager problems.

Using projections for fetching

While we cannot control em.find(...) much, we can try to select only the columns we are

interested in using a query. The result handling when we “project” selected columns into an object

is called the projection. Querydsl can project results using a constructor or bean accessors,

both applicable to entity objects or DTOs.6

Let’s try it:

1 Tuple tuple = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.id, QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.breed.id)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.id.eq(1))

5 .fetchOne();

Our demo code

returns Querydsl Tuple but it can also return a DTO using the constructor expression. We’re

selecting a single entity, but it works the same way for lists as well. I included an expression

returning value of the column breed_id, we have to use an association path – and that raises

questions. Let’s see what SQL is generated for this query.

1 SELECT t0.ID, t0.NAME, t1.ID FROM DOG t0, BREED t1

2 WHERE ((t0.ID = ?) AND (t1.ID = t0.BREED_ID))

EclipseLink does exactly what the JPQL says – but is this the best way?

1 select dog0_.id as col_0_0_, dog0_.name as col_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as col_2_0_

2 from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

Now this is cool – and exactly what I expect from a smart ORM. Of course the breed_id is

directly on the Dog table, there is absolutely no need to join Breed just for its ID. I’d

actually use the dual mapping described previously and select QDog.dog.breedId directly which

avoids join with any provider.

This seems usable and it definitely does not trigger any cascading eager fetch, unless we include

entity expression in the select, e.g. Using QDog.dog.breed could ruin the party as it loads the

whole content of the Breed entity and if it contains any to-one it may get loose. The downside

of this approach is obvious – we have to name all the attributes (columns) we need and it may get

tedious if we have wide tables.

I really did not enjoy doing it for 60+ columns and that’s when you start thinking about code generation or other kind of framework. If you don’t have to, you don’t want to complicate your code with such ideas, so if you are sure you can rely on your ORM with lazy load even for to-one then do that. If you can’t you have to decide when to use the ORM as-is, probably relying on the second-level cache to offset the performance hit caused by triggered loads, and when to explicitly cherry-pick columns you want to work with.

Mentioning cache, we also have to realize that listing columns will not use an entity cache, but it

may use query cache. We’re getting closer to traditional SQL, just with JPQL shape. If persistence

context contains unflushed changes and flush mode is set to COMMIT query will not see any changes

either. Typically though, flush mode AUTO is used which flushes pending changes before executing

queries.

Entity update scenario

Most applications need to update entities as well – and projections are not very useful in this case. There is a simple and a complex way how to update an entity:

- In the simple case we take whatever came to the service layer (or its equivalent) and simply

push it to the database. We can use

mergeor JPQL (Querydsl) update clauses for this. - In many cases complex business rules requires us to consult the current state of the entity first

and apply the changes in it in a more subtle way than JPA

mergedoes. In this case we have to read the entity, change what needs to be changed and let JPA to update it. Alternatively, we may read just the selection of the columns (projection) and execute an update clause.

If the business rules don’t require it and performance is not an issue I’d recommend using merge

as it’s very easy to understand and does everything for us. It executes SELECT and UPDATE for

us and we don’t have to care about details. For a single entity update in some typical CRUD-based

information system this may be perfect solution that doesn’t involve convoluted code.

If we need to read the entity first I’d first go for em.find(id) applying the changes from an

incoming DTO to it, complying to all the necessary business rules. This also involves one SELECT

and one UPDATE, except that the select may trigger some additional finds across to-one

relationships even if we don’t need them in this update scenario. The whole select stage can be

much faster if we use the second-level cache, as it avoids one round-trip to the database

completely.

To avoid this we can read the information as a projection (or a Tuple) and later execute a

surgical UPDATE clause. This is nicer to our database although we simply cannot get under the

two roundtrips (read and update), unless we use some conversation scope in memory. This also avoids

the interaction with the persistence context, hence takes less memory, avoids dirty checking at the

end of the transaction, etc. The resulting code, naturally, is more complex, reflecting the

complexity of the scenario.

If you don’t mind using the persistence context and you’re fine with using em.find(...) and later

implicit update at the end of transactions you may use entity view described in the next section

to eliminate traversing to-one relationships you’re not interested in.

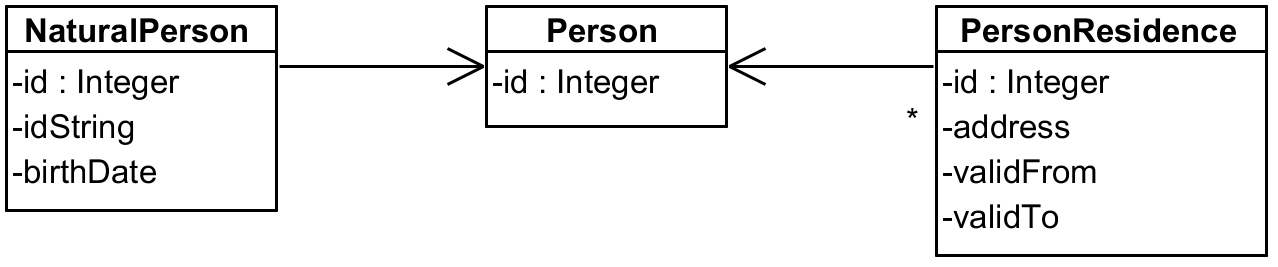

Alternative entity “views”

If we want to solve painful read/update scenario (assuming we know the ID of the entity) and we need to work with only some attributes of the entity we can try to map only those. We will leave full mapping in some “master” class and create another entity that gives us partial view of the selected attributes. I’ll use name entity view for such a class.

The full Dog mapping looks like this:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3 @Id

4 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

5 private Integer id;

6

7 private String name;

8

9 @ManyToOne

10 private Breed breed;

11 ...

We will create alternative view of this entity named DogBasicView (naming sure is hard):

1 @Entity

2 @Table(name = "Dog")

3 public class DogBasicView {

4 @Id