8. Troubles with to-one relationships

Now we can get back to the topics I foreshadowed in the introduction to this opinionated part.

We will show an example of @ManyToOne mapping and we will analyze our options how to load

an entity with such a relationship when we are not interested in its target relation.

Simple example of @ManyToOne

We will continue experimenting on dogs in the demonstration of to-one mapping. The code is

available in a GitHub sub-project many-to-one-eager.

This particular demo project is also referenced in appendix Project example

where particulars of build files and persistence.xml are described. We will skip these but

because this is our first serious experiment in the book we will still include more of the code

listing to establish kind of a baseline.

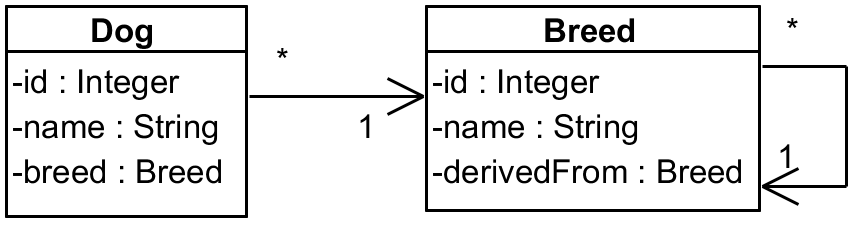

Our model is simple, but there is a twist to it. We have a Dog and Breed entities where a Dog

points to its Breed – and to make things just a little bit tricky the Breed is a hierarchy

where each Breed points to its parent via attribute called derivedFrom.

Our entities are quite plain – Dog looks like this:

1 package modeltoone;

2

3 import javax.persistence.*;

4

5 @Entity

6 public class Dog {

7

8 @Id

9 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

10 private Integer id;

11

12 private String name;

13

14 @ManyToOne

15 private Breed breed;

The rest are getters/setters – complete code is here.

Referenced Breed is mapped like this (full source code):

1 package modeltoone;

2

3 import javax.persistence.*;

4

5 @Entity

6 public class Breed {

7

8 @Id

9 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

10 private Integer id;

11

12 private String name;

13

14 @ManyToOne

15 private Breed derivedFrom;

There is nothing special on these entities, but let’s see what happens when we load some dog. In the process we will also compare Hibernate and EclipseLink, that’s why we have two nearly equivalent persistence units in our persistence.xml. We will prepare data like this:

1 EntityManagerFactory emf = Persistence

2 .createEntityManagerFactory(persistenceUnitName);

3 try {

4 EntityManager em = emf.createEntityManager();

5 em.getTransaction().begin();

6

7 Breed wolf = new Breed();

8 wolf.setName("wolf");

9 em.persist(wolf);

10

11 Breed germanShepherd = new Breed();

12 germanShepherd.setName("german shepherd");

13 germanShepherd.setDerivedFrom(wolf);

14 em.persist(germanShepherd);

15

16 Breed collie = new Breed();

17 collie.setName("collie");

18 collie.setDerivedFrom(germanShepherd);

19 em.persist(collie);

20

21 Dog lassie = new Dog();

22 lassie.setName("Lassie");

23 lassie.setBreed(collie);

24 em.persist(lassie);

25

26 em.getTransaction().commit();

27 em.clear();

28 emf.getCache().evictAll();

29

30 // here comes "demo" code

31 } finally {

32 emf.close();

33 }

Sorry for copy/pasting, eventually the breed and dog creation would end up in separate methods, but for our demo this code will do. Also the breed tree is probably far from reality, but that’s not the point. Let’s say that collie was bred from shepherd which descends from wolf.

Notice the clearing of the entity manager, alternatively we could close and reopen one. Another thing is we are clearing up the second-level cache as well. We may argue what the real case is, but unless you have all your entities cached all the time an empty cache simulates real-life scenario. And we’re just finding the dog by its ID – we know it’s 1:

1 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

What happens at this line? Let’s see the console for Hibernate (manually wrapped):

1 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

2 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_, breed1_.id as id1_0_1_, breed1_.derivedFrom_id

3 as derivedF3_0_1_, breed1_.name as name2_0_1_, breed2_.id as id1_0_2_,

4 breed2_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_2_, breed2_.name as name2_0_2_

5 from Dog dog0_

6 left outer join Breed breed1_ on dog0_.breed_id=breed1_.id

7 left outer join Breed breed2_ on breed1_.derivedFrom_id=breed2_.id

8 where dog0_.id=?

9 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as

10 derivedF3_0_0_, breed0_.name as name2_0_0_, breed1_.id as id1_0_1_,

11 breed1_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_1_, breed1_.name as name2_0_1_

12 from Breed breed0_

13 left outer join Breed breed1_ on breed0_.derivedFrom_id=breed1_.id

14 where breed0_.id=?

Two selects that load a dog and all three breeds – not that bad. If you know traverse up the breed tree, there would be no more select. On the other hand, if you cared about the actual breed of this dog and not about what this breed is derived from we fetched those unnecessarily. There is no way to tell the JPA that dummy breed with shepherd’s ID would do on the collie entity and that you don’t want this to-one relationship fetching to propagate any further.

Let’s look at EclipseLink now:

1 SELECT ID, NAME, BREED_ID FROM DOG WHERE (ID = ?)

2 bind => [1]

3 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

4 bind => [3]

5 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

6 bind => [2]

7 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

8 bind => [1]

This is as obvious as it gets. Each entity is loaded with a separate query. Effect is the same like with Hibernate, EclipseLink just needs more round-trips to the database. Personally I don’t care how many selects it takes in the end as this is part of the JPA provider strategy. We are not going to fine-tune Hibernate or EclipseLink. We’re going to cut off this loading chain.

How about going lazy?

Let’s be a bit naive (I was!) and mark the relationships as lazy:

1 @ManyToOne(fetch = FetchType.LAZY)

2 private Breed breed;

And the same for Breed.derivedFrom. Our testing code is like this:

1 System.out.println("\nfind");

2 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

3 System.out.println("\ntraversing");

4 Breed breed = dog.getBreed();

5 while (breed.getDerivedFrom() != null) {

6 breed = breed.getDerivedFrom();

7 }

8 System.out.println("breed = " + breed.getName());

This way we should see what selects are executed when. Hibernate out of the box works as expected:

1 find

2 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

3 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_ from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

4

5 traversing

6 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

7 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

8 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

9 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

10 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

11 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

12 breed = wolf

Selects are executed as needed (lazily). For long-term Hibernate users this often gives an impression that it should work like this. Let’s migrate to EclipseLink then:

1 find

2 SELECT ID, NAME, BREED_ID FROM DOG WHERE (ID = ?)

3 bind => [1]

4 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

5 bind => [3]

6 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

7 bind => [2]

8 SELECT ID, NAME, DERIVEDFROM_ID FROM BREED WHERE (ID = ?)

9 bind => [1]

10

11 traversing

12 breed = wolf

Just like before EclipseLink generates four selects and executes them right away when you find the entity. How is this possible? Firstly, from the [JPspec] perspective (section 2.2):

Footnote [4] is important here, obviously. So “it should” but it’s just “a hint”.

These results can be recreated by running SingleEntityReadLazy (in test classpath) from GitHub sub-project

many-to-one-lazy.

How bulletproof is Hibernate’s solution?

Pretty much bulletproof, I have to say. As presented here, we annotated fields, which means we

implied Access(FIELD). Hibernate can’t get away with just intercepting getters/setters, it has

to do better. Let’s try a bit of reflection:

1 System.out.println("\nfind");

2 Dog dog = em.find(Dog.class, 1);

3 System.out.println("\nhacking");

4 Field breedField = dog.getClass().getDeclaredField("breed");

5 System.out.println(breedField.getType());

6 breedField.setAccessible(true);

7 Object val = breedField.get(dog);

8 System.out.println("val = " + val);

And now the console output mixed with logs:

1 find

2 Hibernate: select dog0_.id as id1_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as breed_id3_1_0_,

3 dog0_.name as name2_1_0_ from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

4

5 hacking

6 class modeltoone.Breed

7 Hibernate: select breed0_.id as id1_0_0_, breed0_.derivedFrom_id as derivedF3_0_0_,

8 breed0_.name as name2_0_0_ from Breed breed0_ where breed0_.id=?

9 val = Breed{id=3, name='collie'}

This is perfectly lazy. The solution seems even magic when you think about it.

Lazy to-one not guaranteed

Doing lazy collection (@OneToMany or @ManyToMany) is not a problem,

we would probably mess around a bit but eventually we would create some collection implementation

that does it right. The trick is we have the actual entities wrapped in a collection that works

as an intermediary. We don’t need to perform any bytecode voodoo on the entity class.

With to-one situation changes dramatically as you have no intermediary. It would be interesting if JPA at least offered some wrapper to enforce lazy behaviour when you really need it regardless of the JPA provider, but that would give away you’re using some ORM (like you don’t know) and even more voices would talk about that “leaking abstraction”.

While my tests with Hibernate looked great, the results are not portable across JPA providers as we saw. Also, I’d not bet that you’ll get the same results because there’s still a lot of questions how to make Hibernate lazy for to-one relationships, many of them quite new.

So the whole trouble with to-one is that you rely on out-of-language features (bytecode

manipulation) for LAZY support or suffer potentially very costly cascade of relation loading.

The cost may be alleviated by a cache somewhat, but you just trade CPU/network cost for memory

(and CPU for GC, mind you) – even if you don’t need most of the loaded data at all (maybe ever).

Also, LAZY can work perfectly for WAR application in Java EE container but it may suddenly stop

working when switching to embedded container. I’m not saying that LAZY is not worth the trouble,

on the contrary, I believe that lazy relationship is essential for both to-many (as default) and

to-one (in most circumstances) but it indeed can be a lot of trouble during the build time or

runtime, especially in Java SE environment. Java EE with its default provider may be nice to us,

but it still isn’t guaranteed.

Dual relationship mapping

When I say dual mapping I mean mapping of the relationship both as an object and foreign key value. It looks like this:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3 ...

4 @ManyToOne

5 @JoinColumn(name = "breed_id", updatable = false, insertable = false)

6 private Breed breed;

7

8 @Column(name = "breed_id")

9 private Integer breedId;

I can’t find example of this anywhere in the [JPspec], neither can I find anything

that would forbid it (although I’m not really sure) – but it works in both major JPA providers.

The key is marking one of these attributes as readonly, that’s what updatable/insertable=false

does. The other mapping is primary – the one used for updates. I prefer when the raw foreign key

is primary because now I don’t need any Breed object for update when I have its ID already (it’s

easy to extract ID from the object if I have it too). Getters are returning values for respective

fields, setters are designed in such a way that the persisted field (here foreign key value) is

always updated:

1 public Breed getBreed() {

2 return breed;

3 }

4

5 public void setBreed(Breed breed) {

6 this.breed = breed;

7 breedId = breed.getId();

8 }

9

10 public Integer getBreedId() {

11 return breedId;

12 }

13

14 public void setBreedId(Integer breedId) {

15 this.breedId = breedId;

16 }

In this case it means merely setting the breedId field when breed is updated. We don’t care

about breed in the other setter. Programmer has to know that foreign key value is primary

breed attribute here and act accordingly. For instance, this setup is not transparent when

persisting new entities. If we persist a fresh breed there is no guarantee its ID is already

available as autoincrement fields are filled in after the actual INSERT is flushed to the

database. With EclipseLink we have to force it if we need the ID – calling setBreed(newBreed)

would otherwise set dog’s FK to the breed to null. Hibernate is rather eager with INSERTs which

is convenient for this scenario.

The reverse case – with breed as the persisted field and breedId as the readonly one – is less

useful and I cannot find any reasons to use it instead of the traditional JPA relationship mapping.

You can get foreign key value anytime calling breed.getId().

In any case, there are no “savings” during the load phase, but we can store new entities with

raw foreign key values if we have those (and for whatever reason don’t have the entities loaded).

Previously we mentioned the possibility of using entities as wrappers for the foreign keys, but we

also showed that it doesn’t play well with cascade = PERSIST.

If we go back to dreaming – imagine we could request em.find for a dog by ID with a hint not

to load readonly mappings (or otherwise designated). This would save us the hassle during the

loading phase as well and made the whole read-update scenario (part of typical CRUD) based on

foreign key values with the opportunity to load the relationships – if we wished so. Any of this

could be specified on the entity level based on typical patterns of usage. Imagine all the people

/ fetching like they want. Oh-oh… (Lennon/Richter)

Dual mapping like this has one big advantage compared to the pure foreign key mapping – with

the breed mapping we can construct JPA compliant JPQL queries without waiting for the next

version of JPA – if they bring the option of joining root entities at all, that is. But currently

dual mapping also means that we can only avoid the fetch cascade if we:

- Rely on

LAZYhint – not guaranteed by JPA, but if provided by a provider, you can consider it solved. - Or we query the entity with all the columns named explicitly (e.g. include

breedId, but skipbreed) – this, however, cripples the caching (if you use it), you don’t get attached entity and (above all) it is annoying to code. We will talk more about this in the following sections.

So, dual mapping is an interesting tool but does not allow us to avoid all the eager problems.

Using projections for fetching

While we cannot control em.find(...) much, we can try to select only the columns we are

interested in using a query. The result handling when we “project” selected columns into an object

is called the projection. Querydsl can project results using a constructor or bean accessors,

both applicable to entity objects or DTOs.6

Let’s try it:

1 Tuple tuple = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.id, QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.breed.id)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.id.eq(1))

5 .fetchOne();

Our demo code

returns Querydsl Tuple but it can also return a DTO using the constructor expression. We’re

selecting a single entity, but it works the same way for lists as well. I included an expression

returning value of the column breed_id, we have to use an association path – and that raises

questions. Let’s see what SQL is generated for this query.

1 SELECT t0.ID, t0.NAME, t1.ID FROM DOG t0, BREED t1

2 WHERE ((t0.ID = ?) AND (t1.ID = t0.BREED_ID))

EclipseLink does exactly what the JPQL says – but is this the best way?

1 select dog0_.id as col_0_0_, dog0_.name as col_1_0_, dog0_.breed_id as col_2_0_

2 from Dog dog0_ where dog0_.id=?

Now this is cool – and exactly what I expect from a smart ORM. Of course the breed_id is

directly on the Dog table, there is absolutely no need to join Breed just for its ID. I’d

actually use the dual mapping described previously and select QDog.dog.breedId directly which

avoids join with any provider.

This seems usable and it definitely does not trigger any cascading eager fetch, unless we include

entity expression in the select, e.g. Using QDog.dog.breed could ruin the party as it loads the

whole content of the Breed entity and if it contains any to-one it may get loose. The downside

of this approach is obvious – we have to name all the attributes (columns) we need and it may get

tedious if we have wide tables.

I really did not enjoy doing it for 60+ columns and that’s when you start thinking about code generation or other kind of framework. If you don’t have to, you don’t want to complicate your code with such ideas, so if you are sure you can rely on your ORM with lazy load even for to-one then do that. If you can’t you have to decide when to use the ORM as-is, probably relying on the second-level cache to offset the performance hit caused by triggered loads, and when to explicitly cherry-pick columns you want to work with.

Mentioning cache, we also have to realize that listing columns will not use an entity cache, but it

may use query cache. We’re getting closer to traditional SQL, just with JPQL shape. If persistence

context contains unflushed changes and flush mode is set to COMMIT query will not see any changes

either. Typically though, flush mode AUTO is used which flushes pending changes before executing

queries.

Entity update scenario

Most applications need to update entities as well – and projections are not very useful in this case. There is a simple and a complex way how to update an entity:

- In the simple case we take whatever came to the service layer (or its equivalent) and simply

push it to the database. We can use

mergeor JPQL (Querydsl) update clauses for this. - In many cases complex business rules requires us to consult the current state of the entity first

and apply the changes in it in a more subtle way than JPA

mergedoes. In this case we have to read the entity, change what needs to be changed and let JPA to update it. Alternatively, we may read just the selection of the columns (projection) and execute an update clause.

If the business rules don’t require it and performance is not an issue I’d recommend using merge

as it’s very easy to understand and does everything for us. It executes SELECT and UPDATE for

us and we don’t have to care about details. For a single entity update in some typical CRUD-based

information system this may be perfect solution that doesn’t involve convoluted code.

If we need to read the entity first I’d first go for em.find(id) applying the changes from an

incoming DTO to it, complying to all the necessary business rules. This also involves one SELECT

and one UPDATE, except that the select may trigger some additional finds across to-one

relationships even if we don’t need them in this update scenario. The whole select stage can be

much faster if we use the second-level cache, as it avoids one round-trip to the database

completely.

To avoid this we can read the information as a projection (or a Tuple) and later execute a

surgical UPDATE clause. This is nicer to our database although we simply cannot get under the

two roundtrips (read and update), unless we use some conversation scope in memory. This also avoids

the interaction with the persistence context, hence takes less memory, avoids dirty checking at the

end of the transaction, etc. The resulting code, naturally, is more complex, reflecting the

complexity of the scenario.

If you don’t mind using the persistence context and you’re fine with using em.find(...) and later

implicit update at the end of transactions you may use entity view described in the next section

to eliminate traversing to-one relationships you’re not interested in.

Alternative entity “views”

If we want to solve painful read/update scenario (assuming we know the ID of the entity) and we need to work with only some attributes of the entity we can try to map only those. We will leave full mapping in some “master” class and create another entity that gives us partial view of the selected attributes. I’ll use name entity view for such a class.

The full Dog mapping looks like this:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3 @Id

4 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

5 private Integer id;

6

7 private String name;

8

9 @ManyToOne

10 private Breed breed;

11 ...

We will create alternative view of this entity named DogBasicView (naming sure is hard):

1 @Entity

2 @Table(name = "Dog")

3 public class DogBasicView {

4 @Id

5 @Column(updatable = false)

6 private Integer id;

7

8 private String name;

The difference is we didn’t map the breed because, presumably, we don’t want to touch it in some “Edit dog’s basic attributes” form. In real life it doesn’t have to be just a name, it can plenty of attributes without just some you don’t need.

Now if we read DogBasicView, change it and wait for the end of the transaction only the columns

in the entity view will be modified. We have a guarantee that UPDATE will not mention any

unmapped columns. That means that you can use various entity views for various update scenarios.

Such an entity view should result in much less code as you don’t have to name any columns in a

projection (and the related constructor), you simply map them in a particular entity view.

Using entity view for pure reading is sub-optimal compared to projections as mentioned previously (memory, dirty-checking, …) but for straightforward update scenarios where original state of the entity is still important as well, e.g. for validation and access permission purposes, impact on the persistence context may be within your tolerance. Using projection and explicit update instead can be an overkill making the code unnecessarily complicated.

There are couple of points you have to keep in your mind though:

- Never combine various “views” of the same entity in the same persistence context. They all live

their own life and you cannot expect that

dogBasic.setName(...)will affect the state of a different entity instance of different typeDogeven though they both represent the same dog in the database. - Our

DogBasicViewwill have its own space not only in the “first-level cache” (persistence context) but also in the second-level cache. I’d be very careful about caching an entity with couple of different classes representing the same table. (Read: I’d not cache it at all, but that’s my personal taste. You definitely want to check how the caching works in such situations.)

Using entity views in JOINs

Because of the missing foreign keys these entity views are unusable when we want to show a table

of results from joined query (e.g. dogs and their breeds). While we could use a subquery in an

IN clause for filtering we still need a JOIN to actually get the data. For displaying tables

DTOs and things like constructor projection seem to be the right answer, however cumbersome.

But if we fetch some data only for reading (e.g. to view them) it is recommended to bypass the

persistence context anyway, especially for performance reasons. And we’re not talking about some

marginal optimization, we’re talking about common sense and a significant waste of

resources.7

If we have raw foreign key values mapped in the entity view we can use non-standard approach supported by all major JPA providers – we will discuss this in the next chapter. However, for pure reads you really should prefer projections.

Entity views and auto-generated schema

In most cases we don’t have to think about schema generation but what if we do? What if we have

lines like this in our persistence.xml?

1 <property name="javax.persistence.schema-generation.database.action" value="create"/>

We utilized the property standardized in the JPA 2.1 and we expect the JPA provider will generate

schema in the database for us. This is particularly handy when we run various tests or short demos.

Now what happens when we declare two entities for the same table in persistence.xml?

1 <persistence-unit ...>

2 ...

3 <class>modeltoone.Dog</class>

4 <class>modeltoone.DogBasicView</class>

5 ...

When we run any demo using this persistence unit we can check the log and see the CREATE

statements it uses. With EclipseLink there will be a single one for our Dog:

1 CREATE TABLE DOG (ID INTEGER IDENTITY NOT NULL, NAME VARCHAR,

2 BREED_ID INTEGER, PRIMARY KEY (ID))

And it contains all the necessary columns. But if we switch the order in persistence.xml

EclipseLink generates the table based on DogBasicView and it will miss the breed_id column.

Hibernate scans for the classes even in SE environment (but only within the JAR file containing

persistence.xml) and if you want to try the effect of the order of <class> elements in

persistence.xml you also have to include this:

1 <exclude-unlisted-classes>true</exclude-unlisted-classes>

But the order does not affect Hibernate, it somehow picks the “widest” class for the table and

creates the table based on it. It works this way without putting classes in the XML as well. What

happens if the main Dog entity does not have all the columns mapped and one of the entity views

has additional column? Let’s say DogWithColor has a color column that is not present in Dog

class.

This is not a good situation – neither EclipseLink nor Hibernate can deal with it. EclipseLink

generates the table based on whatever entity is first in the list and Hibernate picks some

candidate. I’m not exactly sure about Hibernate’s algorithm as it’s not an alphabetical order

either, somehow it seems to find the best candidate in my limited test cases. But it does not union

all the columns from all the entities for the same table and that means it has to choose between

the Dog and the DogWithColor – and that means some columns will not be generated.

Summary

With current state of the standard there are following options available:

- Leave to-one as

EAGERand compensate with caches. - Configure your ORM to make it

LAZY. This may be easy, it may even be provided out of the box, but it can also change with an upgrade or depend on the environment (Java SE/EE). It is simply not guaranteed by the JPA standard. - Select only the columns you’re interested in. This is very cumbersome for read/update scenarios of a single entity and bearable but still inconvenient for selecting of lists for tables, etc.

- Use entity views, that is to map the same table with multiple classes based on the use case you want to cover. This is very practical for read/update scenarios when you can fetch by entity’s ID.

In any of these cases you can also use dual mapping – mapping both the foreign key value and the relationship as an object. When mapping more attributes for a single column we have to designate other mappings as read-only. If we just could explicitly ask JPA to fetch the object – or ask it not to fetch – we would have much better control over the fetching cascade going wild.

Dual mapping foreshadows the next chapter in which I’m going to present an alternative that is not JPA compliant, but tries to do without to-one relations altogether. It can be used by all major JPA 2.1 providers but if you insist on pure JPA you are free to just skip those pages.