III Common problems

After the previous part this one will be more relaxed. We will talk about couple of typical problems related to the use of ORM/JPA, some of them stemming from the underlying relational model. We will try to load our data in an appropriate manner, avoiding executing many unnecessary statements or adding superfluous joins where possible.

Finally we will wrap it all with more advanced Querydsl topics.

Unlike in the previous part there is no recommended order of the chapters and you can read any of them as you like.

11. Avoid N+1 select

While performance tuning is not the main goal of this book we should follow some elementary performance common sense. If we can avoid an unnecessary query we should do so. With ORM/JPA we can generate a lot of needless queries without even realizing. In this chapter we will cover the most pronounced problem called N+1 select.

Anatomy of N+1 select

I’d prefer to call this problem 1+N because it mostly starts with one query that returns N rows and induces up to N additional queries. While addition is commutative, hence 1+N is the same like N+1, I’ll stick to N+1 as usually used in literature. The typical scenarios when the N+1 problem appears are:

- Query for N entities that have eager to-one relationship – or more of them – and the provider is not smart enough to use joins.

- Query for N entities that have eager to-many relationship and the provider is either not smart enough to use the join (again) or it is not possible to use it for other reasons like pagination. We will cover paginating of entities with to-many later in this chapter.

- Query for N entities with lazy relationship that is triggered later, e.g. in the view as usual with the Open Session in View (OSIV) pattern.

There are probably more scenarios, but these are the most typical ones. First let’s look at the eager examples.

Eager to-one without joins

If you recall our simple example with @ManyToOne from the chapter

Troubles with to-one relationships you know that to-one relationships

may trigger additional fetching. These may result in DB queries or they can be found in the

cache – depends on your setting – and this all must be taken into consideration.

For the next sections let’s use the following data for dogs and their owners:

| id | name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Adam |

| 2 | Charlie |

| 3 | Joe |

| 4 | Mike |

| id | name | owner_id |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alan | 1 (Adam) |

| 2 | Beastie | 1 (Adam) |

| 3 | Cessna | 1 (Adam) |

| 4 | Rex | 3 (Joe) |

| 5 | Lassie | 3 (Joe) |

| 6 | Dunco | 4 (Mike) |

| 7 | Goro | NULL |

Our mapping for the Dog looks like this:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3

4 @Id

5 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

6 private Integer id;

7

8 private String name;

9

10 @ManyToOne(fetch = FetchType.EAGER)

11 @JoinColumn(name = "owner_id")

12 private Owner owner;

And for the Owner:

1 @Entity

2 public class Owner implements Serializable {

3

4 @Id

5 @GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

6 private Integer id;

7

8 private String name;

9

10 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "owner")

11 private Set<Dog> dogs;

Now let’s list all the dogs with this code:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .fetch();

We get seven dogs for three different owners (one dog is not owned) but what happened on the SQL level? Both Hibernate and EclipseLink do something like this (output from EclipseLink):

1 SELECT ID, NAME, OWNER_ID FROM DOG

2 SELECT ID, NAME FROM OWNER WHERE (ID = 1)

3 SELECT ID, NAME FROM OWNER WHERE (ID = 3)

4 SELECT ID, NAME FROM OWNER WHERE (ID = 4)

That classifies as N+1 problem, although the N may be lower than the count of

selected rows thanks to the persistence context. JPA providers may be persuaded to use JOIN

to fetch the information but this is beyond the current version of JPA specification. EclipseLink

offers @JoinFetch(JoinFetchType.OUTER) and Hibernate has @Fetch(FetchMode.JOIN) (also uses

outer select). In a related demo

I tried both and to my surprise EclipseLink obeyed but Hibernate did not – which went against my

previous experiences that Hibernate tries to optimize queries better in general.

Now, what if we don’t need any data for owner? You may try to use lazy fetch for the data you

don’t need if you know you can rely on LAZY or try some other technique described in

Troubles with to-one relationships. Here entity views come to mind, but

projections may be even better.

Anytime I wanted to load dogs with their owners I’d go for explicit JOIN. Let’s see how to

do that properly. Even though we don’t use the owners in select it is not sufficient construct

query like this:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog.owner)

5 .fetch();

This results in an invalid JPQL query:

1 select dog

2 from Dog dog

3 left join dog.owner

While this runs on Hibernate, it fails on EclipseLink with a syntax error: An identification variable must be defined for a JOIN expression. This, indeed, is necessary according to the specification and we must add an alias like so:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog.owner, QOwner.owner)

5 .fetch();

This results in a valid JPQL query:

1 select dog

2 from Dog dog

3 left join dog.owner as owner

But without using it in select – which we don’t want because we don’t want the list of

Tuples – we end up with a query with our join, but the data for owners is still not fetched

and N additional queries are executed just like before. Had we used it in the select it would be

fetched, of course.

The right way to do it if we insist on the result typed as List<Dog> is this:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog.owner).fetchJoin()

5 .fetch();

This results in a valid and correct JPQL query:

1 select dog

2 from Dog dog

3 left join fetch dog.owner

Notice we haven’t used alias this time and looking at BNF

(Backus–Naur form) notation from

[JPspec], section 4.4.5 Joins I believe identification_variable is allowed

only for join and not for fetch_join rules. Nonetheless, both Hibernate and EclipseLink

tolerate this.

Eager to-many relationships

Using EAGER on collections by default is rather risky. I’d personally not use it and use explicit

joins when needed instead. In our example

we will use OwnerEager entity that uses the same table like Owner (hence the same prepared

data) but maps dogs collection as:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "owner", fetch = FetchType.EAGER)

2 private Set<DogEager> dogs;

Now we run the following code:

1 List<OwnerEager> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QOwnerEager.ownerEager)

3 .from(QOwnerEager.ownerEager)

4 .fetch();

5 System.out.println("\nowners = " + owners);

6 for (OwnerEager owner : owners) {

7 System.out.println(owner.getName() + "'s dogs = " + owner.getDogs());

8 }

SQL produced at the point fetch() is executed is (output from EclipseLink, Hibernate is similar):

1 SELECT ID, NAME FROM Owner

2 SELECT ID, NAME, owner_id FROM Dog WHERE (owner_id = ?)

3 SELECT ID, NAME, owner_id FROM Dog WHERE (owner_id = ?)

4 SELECT ID, NAME, owner_id FROM Dog WHERE (owner_id = ?)

5 SELECT ID, NAME, owner_id FROM Dog WHERE (owner_id = ?)

And output of the subsequent print statements (manually wrapped):

1 owners = [Person{id=1, name=Adam}, Person{id=2, name=Charlie},

2 Person{id=3, name=Joe}, Person{id=4, name=Mike}]

3 Adam's dogs = [Dog{id=1, name='Alan', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=2,

4 name='Beastie', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=3, name='Cessna', owner.id=1}]

5 Charlie's dogs = []

6 Joe's dogs = [Dog{id=4, name='Rex', owner.id=3},

7 Dog{id=5, name='Lassie', owner.id=3}]

8 Mike's dogs = [Dog{id=6, name='Dunco', owner.id=4}]

Everything is OK, except it can all be done in a single query. Had we added a single fetch join line in the query we would have had it in a single go:

1 List<OwnerEager> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QOwnerEager.ownerEager)

3 .from(QOwnerEager.ownerEager)

4 .leftJoin(QOwnerEager.ownerEager.dogs).fetchJoin()

5 .fetch();

Join reaches for the data – notice we have to use leftJoin if the collection may be empty – and

fetchJoin takes care of putting them in the collection. This is probably the best what we can

explicitly do with eager collection mapping in place. Resulting SQL (here EclipseLink):

1 SELECT t1.ID, t1.NAME, t0.ID, t0.NAME, t0.owner_id

2 FROM {oj Owner t1 LEFT OUTER JOIN Dog t0 ON (t0.owner_id = t1.ID)}

In general, if eager fetch on collection is not executed using a join on the background it is not worth it. We can get the same N+1 behavior with lazy loads although it may require some explicit code to actually fetch the collection when you want – e.g. in the service layer instead of later in presentation layer with persistence context already not available.

There is one crucial difference between N+1 across to-one and to-many relationships. In case of to-one JPA provider may utilize entity cache as the ID of the needed entity is already available. In case of to-many, on the other hand, we have to execute actual select. This may use query cache – but setting that one appropriately is definitely more tricky than the entity cache. Without caches this difference is blurred away and the only difference is that for to-one we’re accessing rows in DB by its primary key, while for to-many we’re using the foreign key. PK is virtually always indexed, FK not necessarily so – but I guess it should be when we’re using this access pattern.

Perhaps there are some settings or custom annotations that make JPA provider perform the join, but it must be smart enough not to use it when limit/offset is in play. As this capability is not available in JPA – and because I believe eager collections are even worse than eager to-one – we will not delve into it any more.

Lazy relationships triggered later

Lazy fetch is a reasonable default for mapping collections – and it is default according to the specification. Because a collection can be implemented in a custom way all JPA providers offer lazy behaviour without the need for any bytecode magic.

Mapping on the Owner is natural:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "owner")

2 private Set<Dog> dogs;

Now we run the code very similar to the previous section (entity classes are different, but they work on the same tables):

1 List<Owner> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QOwner.owner)

3 .from(QOwner.owner)

4 .fetch();

5 System.out.println("\nowners = " + owners);

6 for (Owner owner : owners) {

7 System.out.println(owner.getName() + "'s dogs = " + owner.getDogs());

8 }

EclipseLink produces the following output (mixing SQL and standard output):

1 SELECT ID, NAME FROM OWNER

2 owners = [Person{id=1, name=Adam}, Person{id=2, name=Charlie},

3 Person{id=3, name=Joe}, Person{id=4, name=Mike}]

4 Adam's dogs = {IndirectSet: not instantiated}

5 Charlie's dogs = {IndirectSet: not instantiated}

6 Joe's dogs = {IndirectSet: not instantiated}

7 Mike's dogs = {IndirectSet: not instantiated}

Is that all? This may seem a bit disturbing and leads us to the question: What should toString

on the lazy collection do?

Hibernate treats toString differently and prints the content as expected:

1 Hibernate: select owner0_.id as id1_1_, owner0_.name as name2_1_

2 from Owner owner0_

3 owners = [Person{id=1, name=Adam}, Person{id=2, name=Charlie},

4 Person{id=3, name=Joe}, Person{id=4, name=Mike}]

5 Hibernate: select dogs0_.owner_id as owner_id3_0_0_,

6 dogs0_.id as id1_0_0_, ...

7 from Dog dogs0_ where dogs0_.owner_id=?

8 Adam's dogs = [Dog{id=1, name='Alan', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=2,

9 name='Beastie', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=3, name='Cessna', owner.id=1}]

10 ...and more for other owners

This toString triggers the lazy load process, just like other methods that do the same for

EclipseLink. This means N+1 problem, of course. Lazy load is supposed to prevent loading the data

that is not needed – sometimes we say that the best queries are the ones we don’t have to perform.

But what if want to display a table of owners and list of their dogs in each row? Postponing the

load into the view is the worst thing we can do for couple of reasons:

- We actually don’t gain anything, we’re still stuck with N+1 problem while there are better ways to load the same data.

- We know what data are needed and the responsibility for their loading is split between backend layer and presentation layer.

- To allow presentation layer to load the data we need to keep persistence context open longer. This leads to the infamous Open Session in View (OSIV) pattern, or rather an antipattern.

When we need the data in the collection we should use join just like we used it for an eager collection – there is actually no difference if we use the join explicitly. But as we demonstrated previously there is the issue with paginating. And that’s what we’re going to talk about next.

Paginating with to-many

I mentioned previously that we can’t escape SQL underneath. If we join another table across to-many relationship we change the number of fetched rows and with that we cannot paginate reliably. We can demonstrate this with SQL or even with Querydsl (that is JPQL).

We will try to obtain owners and their dogs ordered by owner’s name. We will set offset to 1 and

limit to 2 which should return Charlie and Joe. I realize that offset that is not multiple of

limit (that is a page size) does not make best sense, but I want these two particular items for

the following reasons:

- I want to draw from the middle of our owner list, not the beginning or the end.

- I want to see the effect of Charlie’s empty collection.

- I want to see how Joe’s two dogs affect the results.

With our limited data this limit (2) and offset (1) demonstrates all that.

We already saw that both eager and lazy collection allows us to query the master table and let N other queries pull the data:

1 List<Owner> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QOwner.owner)

3 .from(QOwner.owner)

4 .orderBy(QOwner.owner.name.asc())

5 .offset(1)

6 .limit(2)

7 .fetch();

8 for (Owner owner : owners) {

9 owner.getDogs().isEmpty(); // to assure lazy load even on EclipseLink

10 System.out.println(owner.getName() + "'s dogs = " + owner.getDogs());

11 }

Join leads to incorrect results

We can’t fix the N+1 problem with JOIN FETCH anymore:

1 List<Owner> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QOwner.owner)

3 .from(QOwner.owner)

4 .leftJoin(QOwner.owner.dogs).fetchJoin()

5 .orderBy(o.name.asc(), d.name.asc())

6 .offset(1)

7 .limit(2)

8 .fetch();

With the same print loop this produces:

1 Adam's dogs = {[Dog{id=1, name='Alan', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=2, ...

2 Adam's dogs = {[Dog{id=1, name='Alan', owner.id=1}, Dog{id=2, ...

The same happens if we want to be explicit. Here we even use “raw” versions of entities, ad hoc

join (to root entity) and explicit ON:

1 QOwnerRaw o = QOwnerRaw.ownerRaw;

2 QDogRaw d = QDogRaw.dogRaw;

3 List<Tuple> results = new JPAQuery<>(em)

4 .select(o, d)

5 .from(o)

6 .leftJoin(d).on(d.ownerId.eq(o.id))

7 .orderBy(o.name.asc(), d.name.asc())

8 .offset(1)

9 .limit(2)

10 .fetch();

11 for (Tuple row : results) {

12 DogRaw dog = row.get(d);

13 System.out.println(row.get(o).getName() + ", " +

14 (dog != null ? dog.getName() : null));

15 }

Now we had to change the print loop and we put the results into tuple:

1 Adam, Beastie

2 Adam, Cessna

We could just select(o) but it would still two rows of Adam. Ok, how does the whole result set

looks like and what are we selecting with our limit/offset?

| owner | dog |

|---|---|

| Adam | Alan |

| Adam | Beastie |

| Adam | Cessna |

| Charlie | null |

| Joe | Lassie |

| Joe | Rex |

| Mike | Dunco |

This makes it more obvious. Offset and limit are not smart and they don’t care about what we want to paginate. With values 1 and 2 respectively they will give us lines 2 and 3 of whatever result we apply it to. And that is very important.

Using native SQL

Is it even possible to paginate with a single query? Yes, but we have to use subquery in a FROM

or JOIN clause, neither of which is available in JPQL (as of JPA 2.1). We can try native query:

1 // select * would be enough for EclipseLink

2 // Hibernate would complains about duplicated sql alias

3 Query nativeQuery = em.createNativeQuery(

4 "SELECT o.name AS oname, d.name AS dname" +

5 " FROM (SELECT * FROM owner LIMIT 2 OFFSET 1) o" +

6 " LEFT JOIN dog d ON o.id=d.owner_id");

7 List<Object[]> resultList = nativeQuery.getResultList();

8

9 System.out.println("resultList = " + resultList.stream()

10 .map(row -> Arrays.toString(row))

11 .collect(Collectors.toList()));

Returned resultList has three rows:

1 resultList = [[Charlie, null], [Joe, Rex], [Joe, Lassie]]

But all rows are related to our two selected owners. We got all the data in relational form,

there is no other way, it’s up to us to group the data as we need. For this we may want to add

a transient dogs collection in our “raw” variant of the Owner class.

JPA/Querydsl solutions

Because of current JPQL disabilities we cannot do it all in one go, but we can do it in a single additional query:

1) Query with pagination is executed. This may return some data from the master table or perhaps only IDs of the rows. Order must be applied for pagination to work correctly. Any where conditions are applied here as well, more about it in a moment. 2) Fetch the missing data limiting the results to the scope of the previous result. The concrete implementation of this step differs depending on the nature of the first query.

Let’s say the first query just returns IDs like this:

1 QOwnerRaw o = QOwnerRaw.ownerRaw;

2 List<Integer> ownerIds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(o.id)

4 .from(o)

5 .orderBy(o.name.asc())

6 // WHERE ad lib here

7 .offset(1)

8 .limit(2)

9 .fetch();

In this case we can get the final result like this:

1 QDogRaw d = QDogRaw.dogRaw;

2 Map<OwnerRaw, List<DogRaw>> ownerDogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(o, d)

4 .from(o)

5 .leftJoin(d).on(d.ownerId.eq(o.id))

6 .where(o.id.in(ownerIds))

7 .orderBy(o.name.asc()) // use the same order as in select #1

8 .orderBy(d.name.desc()) // dogs in each list ordered DESC

9 // no limit/offset, where took care of it

10 .transform(groupBy(o).as(list(d)));

11 System.out.println("ownerDogs = " + ownerDogs);

We will talk more about transform method later in the chapter on advanced Querydsl, and its

section result transformation. Obviously it is the trick that allows

us to return Map instead of List.

Using the same order like in the first query is essential, additional orders are allowed. Important

question is whether you need to join any to-many relationship for the first query as well. If we

need to (e.g. for WHERE conditions) we have to use DISTINCT which means we also have to bring

expression from ORDER BY into the SELECT clause. This is mandated by SQL, because DISTINCT

must be applied before we can order the results. This complicates the first select:

1 List<Integer> ownerIds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 // If distinct is used SQL requires o.name here because it is used to

3 // order which happens after distinct. EclipseLink can handle this,

4 // Hibernate generated SQL fails. JPA spec is not specific on this.

5 .select(o.id, o.name)

6 // or perhaps just use o, that encompasses o.name

7 // .select(o)

8 .distinct() // needed if join across to-many is used to allow WHERE

9 .from(o)

10 .orderBy(o.name.asc())

11 // WHERE ad lib here

12 .offset(1)

13 .limit(2)

14 .fetch()

15 .stream()

16 .map(t -> t.get(o.id))

17 // .map(Owner::getId) // if .select(o) was used

18 .collect(Collectors.toList());

We could stop at fetch and deal with the List<Tuple> but that’s not what we wanted hence the

additional mapping to the list of IDs. The commented version using just o alias and more

straightforward mapping to ID is probably better, but it still raises the question: Do we really

need to join across to-many to add where conditions? Can’t we work around it with subquery? For

example, to get owners with some dogs we can do this with join across to-many:

1 QOwnerRaw o = QOwnerRaw.ownerRaw;

2 QDogRaw d = QDogRaw.dogRaw;

3 List<OwnerRaw> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

4 .select(o)

5 .distinct()

6 .from(o)

7 .leftJoin(d).on(d.ownerId.eq(o.id))

8 .where(d.isNotNull())

9 .orderBy(o.name.asc())

10 .offset(1)

11 .limit(2)

12 .fetch();

This skips Charlie and returns Joe and Mike. We can get the same without JOIN and DISTINCT:

1 QOwnerRaw o = QOwnerRaw.ownerRaw;

2 QDogRaw d = QDogRaw.dogRaw;

3 List<OwnerRaw> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

4 .select(o)

5 .from(o)

6 .where(new JPAQuery<>()

7 .select(d)

8 .from(d)

9 .where(d.ownerId.eq(o.id))

10 .exists())

11 .orderBy(o.name.asc())

12 .offset(1)

13 .limit(2)

14 .fetch();

Subquery reads a bit longer but if we wanted to select o.id directly it would save a lot of

troubles we would encounter because of the distinct/orderBy combo.

Personally I’m not a friend of the first select returning only IDs, although there may be scenarios

when it’s the best solution. Now we know we can filter list of owners by dog’s attributes (that is

across to-many relationship), either using subqueries or distinct clause, I’d suggest returning

whole owners. We can safely join any to-one associations and return Tuple of many entities or

we can enumerate all the desired columns and return custom DTO (projection). Projection would

further relieve the persistence context if the data merely flow through the service layer to the

presentation layer.

In the second query we don’t have to load the actual results anymore, the query is needed only for fetching the data in to-many relationship. But we fetch all of it for all the items on the page currently being displayed.

To-many relationship fetcher

To demonstrate how we can implement this fetching pattern I decided to build “quick and dirty” fluent API for the second query. It not only executes the fetch for the to-many relationship for all the items in the page, but it also merges them into a single object – which is a kind of post-processing we glossed over.

I’m not saying it can’t be done better but I think if it looked like this it would be really useful:

1 QOwnerRaw o = QOwnerRaw.ownerRaw;

2 List<OwnerRaw> owners = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(o)

4 .from(o)

5 .orderBy(o.name.asc())

6 .offset(1)

7 .limit(2)

8 .fetch();

9

10 QDogRaw d = QDogRaw.dogRaw;

11 List<OwnerRaw> ownersWithDogs = ToManyFetcher.forItems(owners)

12 .by(OwnerRaw::getId)

13 .from(d)

14 .joiningOn(d.ownerId)

15 .orderBy(d.name.desc())

16 .fetchAndCombine(em, OwnerRaw::setDogs);

This implies some transient dogs collection on the owner and existing setter:

1 @Transient

2 private List<DogRaw> dogs;

3

4 //...

5

6 public void setDogs(List<DogRaw> dogs) {

7 this.dogs = dogs;

8 }

Or we can combine both in some DTO like this (first query is still the same):

1 // first query up to QDogRaw d = ... here

2 List<OwnerWithDogs> ownersWithDogs = ToManyFetcher.forItems(owners)

3 .by(OwnerRaw::getId)

4 .from(d)

5 .joiningOn(d.ownerId)

6 .orderBy(d.name.desc())

7 .fetchAs(em, OwnerWithDogs::new);

8

9 // elsewhere...

10 public class OwnerWithDogs {

11 public final OwnerRaw owner;

12 public final List<DogRaw> dogs;

13

14 OwnerWithDogs(OwnerRaw owner, List<DogRaw> dogs) {

15 this.owner = owner;

16 this.dogs = dogs;

17 }

18 }

Ok, now how to construct such an API? We can use paths of Querydsl – although we don’t use its type-safety capabilities for perfect result – rather we go for something useful without putting too many parametrized type in the code. Also, in order to make it fluent with the need of adding additional parametrized types, I broke my personal rules about code nesting – in this case the nesting of inner classes. Sorry for that, it’s up to you to do it your way, this really is just a proof of concept:

1 import com.querydsl.core.types.*;

2 import com.querydsl.core.types.dsl.*;

3 import com.querydsl.jpa.impl.JPAQuery;

4

5 import javax.persistence.EntityManager;

6 import java.util.*;

7 import java.util.function.*;

8 import java.util.stream.Collectors;

9

10 import static com.querydsl.core.group.GroupBy.*;

11

12 public class ToManyFetcher<T> {

13

14 private final List<T> rows;

15

16 private ToManyFetcher(List<T> rows) {

17 this.rows = rows;

18 }

19

20 public static <T> ToManyFetcher<T> forItems(List<T> rows) {

21 return new ToManyFetcher<>(rows);

22 }

23

24 public <PK> ToManyFetcherWithIdFunction<PK> by(Function<T, PK> idFunction) {

25 return new ToManyFetcherWithIdFunction<>(idFunction);

26 }

27

28 public class ToManyFetcherWithIdFunction<PK> {

29 private final Function<T, PK> idFunction;

30

31 public ToManyFetcherWithIdFunction(Function<T, PK> idFunction) {

32 this.idFunction = idFunction;

33 }

34

35 public <TMC> ToManyFetcherWithFrom<TMC> from(

36 EntityPathBase<TMC> toManyEntityPathBase)

37 {

38 return new ToManyFetcherWithFrom<>(toManyEntityPathBase);

39 }

40

41 public class ToManyFetcherWithFrom<TMC> {

42 private EntityPathBase<TMC> toManyEntityPathBase;

43 private Path<PK> fkPath;

44 private OrderSpecifier orderSpecifier;

45

46 public ToManyFetcherWithFrom(EntityPathBase<TMC> toManyEntityPathBase)

47 {

48 this.toManyEntityPathBase = toManyEntityPathBase;

49 }

50

51 public ToManyFetcherWithFrom<TMC> joiningOn(Path<PK> fkPath) {

52 this.fkPath = fkPath;

53 return this;

54 }

55

56 public ToManyFetcherWithFrom<TMC> orderBy(OrderSpecifier orderSpecifier) {

57 this.orderSpecifier = orderSpecifier;

58 return this;

59 }

60

61 public <R> List<R> fetchAs(

62 EntityManager em, BiFunction<T, List<TMC>, R> combineFunction)

63 {

64 Map<PK, List<TMC>> toManyResults = getToManyMap(em);

65

66 return rows.stream()

67 .map(row -> combineFunction.apply(row,

68 toManyResults.getOrDefault(

69 idFunction.apply(row), Collections.emptyList())))

70 .collect(Collectors.toList());

71 }

72

73 public List<T> fetchAndCombine(EntityManager em,

74 BiConsumer<T, List<TMC>> combiner)

75 {

76 Map<PK, List<TMC>> toManyResults = getToManyMap(em);

77

78 rows.forEach(row -> combiner.accept(row,

79 toManyResults.getOrDefault(

80 idFunction.apply(row), Collections.emptyList())));

81

82 return rows;

83 }

84

85 private Map<PK, List<TMC>> getToManyMap(EntityManager em) {

86 List<PK> ids = rows.stream()

87 .map(idFunction)

88 .collect(Collectors.toList());

89 JPAQuery<TMC> tmcQuery = new JPAQuery<>(em)

90 .select(toManyEntityPathBase)

91 .from(toManyEntityPathBase)

92 .where(Expressions.booleanOperation(

93 Ops.IN, fkPath, Expressions.constant(ids)));

94 if (orderSpecifier != null) {

95 tmcQuery.orderBy(orderSpecifier);

96 }

97 return tmcQuery

98 .transform(groupBy(fkPath).as(list(toManyEntityPathBase)));

99 }

100 }

101 }

102 }

First we start with ToManyFetcher that preserves the type for the master entity (OwnerRaw in

our example). I could also store EntityManager here – it is eventually needed for query

execution, but I chose to put it into the terminal operation (rather arbitrary decision here).

Method by returns ToManyFetcherWithIdFunction to preserve the type of the master entity

primary key (ID) and also to store the function that maps entity to it. For that we need to return

different type. Next from preserves the type of EntityPathBase of the detail entity (that is

entity Q-class) – and again returns instance of another type that wraps all the accumulated

knowledge.

Further joiningOn and orderBy don’t add any parametrized types so they just return this.

While orderBy is optional, joiningOn is very important and we may construct API in a way that

enforces its call – which did not happen in my demo. Finally we can choose from two handy fetch

operations depending on whether we want to combine the result on the master entity class (using

a setter for instance) or in another type (like DAO).

Java 8 is used nicely here, especially when the API is used. It can certainly be done without

streams but using inner classes instead of lambdas would by and fetch calls arguably unwieldy.

Trying to do it in a single type would require defining all the parametrized types at once –

either explicitly using <....> notation or using a call with multiple arguments.

I tried both and this second fluent approach is much better as the names of fluent calls introduce the parameter and make the code virtually self-documented. I hope this demonstrates how nicely we can use Querydsl API (and Java 8!) for recurring problems.

Wrapping up N+1 problem

N+1 problem can occur when the load of multiple (N) entities subsequently triggers load of their related data one by one. The relations may be to-one or to-many and there may be be multiple of these. The worst case is when the data loaded by up to N additional queries are not used at all. This happens often with to-one relationships which I personally solve with raw FK values – as proposed in the chapter Removing to-one altogether. To-many relationships should be declared as lazy for most cases to avoid “loading the whole DB”.

Needed related data should be loaded explicitly, that is with joins, when we need the data. Scenarios where conscious lazy load is appropriate are rather rare. Scenarios where people either don’t know or are lazy to think are less rare and that’s what leads to N+1 so often. N queries are not necessary in most cases and don’t scale very well with the page size.

For data across to-one relationships there are rarely any negative implications when we join them. With to-many situation gets a little bit messy, especially if we need data across multiple such relationships. If we don’t need pagination we may use join and then group the data appropriately, but with pagination we have to ensure that the driving query on the master entity is paginated correctly. With JPA/JPQL this is typically not possible in a single select and each to-many relationship requires an additional query – but it is possible to keep query count constant and not driven by number of items.

In any case, letting lazy loading doing the job we should do in cases when the data gets loaded anyway is sloppy. Using Open Session in View (OSIV) on top of it instead of having proper service layer contract is plain hazardous.

12. Mapping Java enum

This chapter is based on my two blog posts.

I adapted them for the book and our typical model of dogs and also refined them a bit – there is no need to read the original posts.

Before we embark on our journey we should mention that Java enums are not necessarily the best way to model various code lists and other enumerations. We will tackle this at the end of the chapter.

Typical way how an enumeration is stored in a DB is a numeric column mapped to enum. We all know

that using EnumType.ORDINAL is one of those worse solutions as values returned by ordinal()

get out of control quickly as we evolve the enum – and most of them do. EnumType.STRING is not

loved by our DB admins (if you have them) – even though it’s easy to read for sure. Normalization

suffers, enum constant renaming is a bit problem too. So we want to map it to numeric (for

instance) but not ordinal value. In the entity class we can map it as a raw Integer or as an

enum type – one way or the other we will need to convert back and forth.

We will map them as enum and demonstrate JPA 2.1 converters in the process –

AttributeConverter<X,Y> to be precise.

Only the final version of the code as we get to it at the end of this chapter is included in the repository.

Naive approach

Let’s have our simple enum:

1 public enum Gender {

2 MALE,

3 FEMALE,

4 OTHER

5 }

And we have our entity that is mapping numeric column to our enum:

1 @Entity

2 public class Dog {

3 @Id private Integer id;

4

5 //..

6 @Convert(converter = GenderConverter.class)

7 @Column(name = "gender")

8 private Gender gender;

9 }

This entity will be the same throughout all of our solutions, so we will not repeat it. Important

line is the one with @Convert annotation that allows us to do conversion. All we have to

do now is to implement the converter:

1 import javax.persistence.AttributeConverter;

2 import javax.persistence.Converter;

3

4 /**

5 * This is coupled too much to enum and you always have to change both

6 * classes in tandem. That's a big STOP (and think) sign in any case.

7 */

8 @Converter

9 public class GenderConverter implements AttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

10 @Override

11 public Integer convertToDatabaseColumn(Gender someEntityType) {

12 switch (someEntityType) {

13 case MALE:

14 return 0;

15 case FEMALE:

16 return 1;

17 default:

18 // do we need this? it catches forgotten case when enum is modified

19 throw new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid value " + someEntityType);

20 // the value is valid, just this externalized switch sucks of course

21 }

22 }

23

24 @Override

25 public Gender convertToEntityAttribute(Integer dbValue) {

26 switch (dbValue) {

27 case 0:

28 return Gender.MALE;

29 case 1:

30 return Gender.FEMALE;

31 case 2:

32 return Gender.OTHER;

33 }

34 // now what? probably exception would be better just to warn programmer

35 return null;

36 }

37 }

I revealed the problems in the comments. There may be just one reason to do it this way – when we

need the enum independent from that dbValue mapping. This may be reasonable if the enum is used

in many other contexts. But if storing it in the database is typical we should go for more cohesive

solution. And in this case we will be just fine with encapsulation and put the stuff that changes

on one place – into the enum.

Encapsulated conversion

We still need to implement AttributeConverter because it is kind of glue between JPA and our

class. But there is no reason to leave the actual mapping in this infrastructure class. So let’s

enhance the enum to keep the converter simple. Converter we want to see looks like this:

1 @Converter

2 public class GenderConverter implements AttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

3 @Override

4 public Integer convertToDatabaseColumn(Gender gender) {

5 return gender.toDbValue();

6 }

7

8 @Override

9 public Gender convertToEntityAttribute(Integer dbValue) {

10 // this can still return null unless it throws IllegalArgumentException

11 // which would be in line with enums static valueOf method

12 return Gender.fromDbValue(dbValue);

13 }

14 }

Much better, we don’t have to think about this class at all when we add values to enum. The complexity is now here, but it’s all tight in a single class:

1 public enum Gender {

2 MALE(0),

3 FEMALE(1),

4 OTHER(-1);

5

6 private final Integer dbValue;

7

8 Gender(Integer dbValue) {

9 this.dbValue = dbValue;

10 }

11

12 public Integer toDbValue() {

13 return dbValue;

14 }

15

16 public static final Map<Integer, Gender> dbValues = new HashMap<>();

17

18 static {

19 for (Gender value : values()) {

20 dbValues.put(value.dbValue, value);

21 }

22 }

23

24 public static Gender fromDbValue(Integer dbValue) {

25 // this returns null for invalid value,

26 // check for null and throw exception if you need it

27 return dbValues.get(dbValue);

28 }

29 }

I saw also some half-solutions without the static reverse resolving, but I hope we all agree it

goes into the enum. If it’s two value enum, you may start with switch in fromDbValue, but

that’s just another thing to think about – and one static map will not kill anyone.

Now this works, so let’s imagine we need this for many enums. Can we find some common ground here? I think we can.

Conversion micro-framework

Let’s say we want to have order in these things so we will require the method named toDbValue.

Our enums will implement interface ConvertedEnum:

1 /**

2 * Declares this enum as converted into database, column value of type Y.

3 *

4 * In addition to implementing {@link #toDbValue()} converted enum should also

5 * provide static method for reverse conversion, for instance

6 * {@code X fromDbValue(Y)}. This one should throw {@link

7 * IllegalArgumentException} just as {@link Enum#valueOf(Class, String)} does.

8 * Check {@link EnumAttributeConverter} for helper methods that can be used

9 * during reverse conversion.

10 */

11 public interface ConvertedEnum<Y> {

12 Y toDbValue();

13 }

It’s parametrized, hence flexible. Javadoc says it all – we can’t enforce the static stuff,

because that’s how Java works. While I suggest that reverse fromDbValue should throw

IllegalArgumentException, I’ll leave it to return null for now – just know that I’m aware

of this. I’d personally go strictly for exception but maybe you want to use this method elsewhere

in the code and null works fine for you. We will enforce the exception in our converter instead.

What are the changes in the enum? Minimal really, just add implements ConvertedEnum<Integer> and

you can add @Override for toDbValue method. Not worth the listing. Now to utilize all this we

need a base class implementing AttributeConverter – here it goes:

1 /**

2 * Base implementation for converting enums stored in DB.

3 * Enums must implement {@link ConvertedEnum}.

4 */

5 public abstract class EnumAttributeConverter<X extends ConvertedEnum<Y>, Y>

6 implements AttributeConverter<X, Y>

7 {

8 @Override

9 public final Y convertToDatabaseColumn(X enumValue) {

10 return enumValue != null ? enumValue.toDbValue() : null;

11 }

12

13 @Override

14 public final X convertToEntityAttribute(Y dbValue) {

15 return dbValue != null ? notNull(fromDbValue(dbValue), dbValue) : null;

16 }

17

18 protected abstract X fromDbValue(Y dbValue);

19

20 private X notNull(X x, Y dbValue) {

21 if (x == null) {

22 throw new IllegalArgumentException("No enum constant" +

23 (dbValue != null ? (" for DB value " + dbValue) : ""));

24 }

25 return x;

26 }

27 }

With this our concrete converters only need to provide reverse conversion that requires static

method call to fromDbValue:

1 @Converter

2 public class GenderConverter extends EnumAttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

3 @Override

4 protected Gender fromDbValue(Integer dbValue) {

5 return Gender.fromDbValue(dbValue);

6 }

7 }

What a beauty suddenly! Converter translates null to null which works perfectly with optional

attributes (nullable columns). Null checking should be done on the database level with optional

validation in an application as necessary. However, if invalid non-null value is provided we will

throw aforementioned IllegalArgumentException.

Refinement?

And now the last push. What is repeating? And what we can do about it?

It would be cool to have just a single converter class – but this is impossible, because there is

no way how to instruct the converter about its types. Especially method convertToEntityAttribute

is immune to any approach because there is nothing during runtime that can tell you what the

expected enum type would be. No reflection or anything helps here, so it seems.

So we have to have separate AttributeConverter classes, but can we pull convertToEntityAttribute

into our EnumAttributeConverter? Not easily really, but we’ll try something.

How about the static resolving? Can we get rid of that static initialization block in our enum? It is static, so it seems difficult to abstract it away – but indeed, we can do something about it.

Let’s try to hack our converters first. We need to get the type information into the instance of the superclass. It can be protected field like this:

1 public abstract class EnumAttributeConverter<X extends ConvertedEnum<Y>, Y>

2 implements AttributeConverter<X, Y>

3 {

4 protected Class<X> enumClass;

And subclass would initialize it this way:

1 public class GenderConverter extends EnumAttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

2 {

3 enumClass = Gender.class;

4 }

But this is not enforced in any way! Rather use abstract method that must be implemented. In abstract converter:

1 protected abstract Class<X> enumClass();

And in concrete class:

1 public class GenderConverter extends EnumAttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

2 @Override

3 protected Class<Gender> enumClass() {

4 return Gender.class;

5 }

6 }

But we’re back to 3 lines of code (excluding @Override) and we didn’t get to ugly unified

convertToEntityAttribute:

1 @Override

2 public X convertToEntityAttribute(Y dbValue) {

3 try {

4 Method method = enumClass().getMethod("fromDbValue", dbValue.getClass());

5 return (X) method.invoke(null, dbValue);

6 } catch (IllegalAccessException | InvocationTargetException |

7 NoSuchMethodException e)

8 {

9 throw new IllegalArgumentException("...this really doesn't make sense", e);

10 }

11 }

Maybe I missed something on the path, but this doesn’t sound like good solution. It would be if it

lead to unified converter class, but it did not. There may be one more problem with hunt for

unified solution. While the concrete implementation contains methods that have concrete parameter

and return types, unified abstract implementation don’t. They can use the right types during

runtime, but the method wouldn’t tell you if you used reflection. Imagine JPA checking this.

Right now I know that unified public final Y convertToDatabaseColumn(X x) {...} works with

EclipseLink, but maybe we’re asking for problems. Let’s check it really:

1 // throws NoSuchMethodException

2 // Method method = converter.getClass().getMethod(

3 // "convertToDatabaseColumn", Integer.class);

4 Method method = converter.getClass().getMethod(

5 "convertToDatabaseColumn", Object.class);

6 System.out.println("method = " + method);

This prints:

1 method = public java.lang.Object

2 EnumAttributeConverter.convertToDatabaseColumn(java.lang.Object)

If something strictly matches the method types with column/enum types, we may have

a misunderstanding because our method claims it converts Object to Object. Sometimes too smart

may be just that – way too smart.

Simplified static resolving

Anyway, let’s look into that enum’s static resolving. This is actually really useful. Without further ado, this is how enum part may look like:

1 // static resolving:

2 public static final ConvertedEnumResolver<Gender, Integer> resolver =

3 new ConvertedEnumResolver<>(Gender.class);

4

5 public static Gender fromDbValue(Integer dbValue) {

6 return resolver.get(dbValue);

7 }

So we got rid of the static map and static initializer. But the code must be somewhere:

1 package support;

2

3 import java.util.HashMap;

4 import java.util.Map;

5

6 /**

7 * Helps reverse resolving of {@link ConvertedEnum} from a DB value back to

8 * enum instance. Enums that can be resolved this way must have unified

9 * interface in order to obtain {@link ConvertedEnum#toDbValue()}.

10 *

11 * @param <T> type of an enum

12 * @param <Y> type of DB value

13 */

14 public class ConvertedEnumResolver<T extends ConvertedEnum<Y>, Y> {

15

16 private final String classCanonicalName;

17 private final Map<Y, T> dbValues = new HashMap<>();

18

19 public ConvertedEnumResolver(Class<T> enumClass) {

20 classCanonicalName = enumClass.getCanonicalName();

21 for (T t : enumClass.getEnumConstants()) {

22 dbValues.put(t.toDbValue(), t);

23 }

24 }

25

26 public T get(Y dbValue) {

27 T enumValue = dbValues.get(dbValue);

28 if (enumValue == null) {

29 throw new IllegalArgumentException("No enum constant for dbValue " +

30 dbValue + " in " + classCanonicalName);

31 }

32 return enumValue;

33 }

34 }

And this I actually really like. Here I went for strict checking, throwing exception. Without it or without needing/wanting the type name it could be even shorter. But you write this one once and save in each enum.

So there are three players in this “framework”:

-

ConvertedEnum– interface for your enums that are converted in this way. -

ConvertedEnumResolver– wraps the reverse mapping and saves you most of the static lines in each converted enum. -

EnumAttributeConverter– implements both-way conversion in a unified way, we just need to implement its abstractfromDbValuemethod. Just be aware of potential problems if something introspect the method parameter and return types because these are “generified”.

Alternative conversions within entities

So far we were demonstrating this all in the context of JPA 2.1. I’d like to at least mention alternative solutions for older JPA versions.

If you use AccessType.FIELD then the fields must be strictly in a supported type (that is some

raw type, e.g. Integer for enum), but accessors can do the conversion. If you use

AccessType.PROPERTY than the fields can be in your desired type and you can have two sets of

accessors – one for JPA and other working with the type you desire. You need to mark the latter

as @Transient (or break get/set naming convention).

Long time ago we used this technique to back Dates by long fields (or Long if nullable). This

way various tools (like Sonar) didn’t complain about silly mutable Date breaking the

encapsulation when used directly in get/set methods, because it was not stored directly anymore.

JPA used get/set for Date, and we had @Transient get/set for millis long available. We actually

preferred comparing millis to before/after methods on Date but that’s another story. The same

can be used for mapping enums – just have JPA compatible type mapped for JPA and @Transient

get/set with enum type. Most of the stuff about enum encapsulation and static resolving still

applies.

Java 8 and reverse enum resolution

I focused mostly on conversion to values and back in the context of JPA 2.1 converters. Now we’ll focus on the part that helped us with “reverse resolution”. We have the value – for instance an int, but not ordinal number, of course! – that represents particular enum instance in the database and you want that enum instance. Mapping between these values and enum instances is a bijection, of course.

Our solution so far works fine but there are two limitations:

-

ConvertedEnumResolverdepends on the common interfaceConvertedEnumour enums must implement hence it is implicitly tied to the conversion framework. - If we need another representation (mapping) to different set of values we have to develop new resolver class.

The first one may not be a big deal. The second one is a real thing though. I worked on a system

where enum was represented in the DB as int and elsewhere as String – but we didn’t want

to tie it to the Java enum constant strings. New resolver class was developed – but is another

class really necessary?

Everything in the resolver class is the same – except for the instance method getting the value on the enum. We didn’t want to use any reflection, but we had recently switched to Java 8 and I’d heard it has these method references! If we can pass it to the resolver constructor… is it possible?

Those who know Java 8 know that the answer is indeed positive. Our new resolver will look like this (I renamed it since the last time):

1 /**

2 * Helps reverse resolving of enums from any value back to enum instance.

3 * Resolver uses provided function that obtains value from enum instance.

4 *

5 * @param <T> type of an enum

6 * @param <Y> type of a value

7 */

8 public final class ReverseEnumResolver<T extends Enum, Y> {

9 private final String classCanonicalName;

10 private final Map<Y, T> valueMap = new HashMap<>();

11

12 public ReverseEnumResolver(Class<T> enumClass,

13 Function<T, Y> toValueFunction)

14 {

15 classCanonicalName = enumClass.getCanonicalName();

16 for (T t : enumClass.getEnumConstants()) {

17 valueMap.put(toValueFunction.apply(t), t);

18 }

19 }

20

21 public T get(Y value) {

22 T enumVal = valueMap.get(value);

23

24 if (enumVal == null) {

25 throw new IllegalArgumentException("No enum constant for '" +

26 value + "' in " + classCanonicalName);

27 }

28 return enumVal;

29 }

30 }

There is no conversion mentioned anymore. Just reverse resolving. So, our new enum does not have to

be “Converted” anymore – unless you still need this interface for JPA conversion (which you may).

Let’s show complete listing of our Gender enum that this time can be converted in two sets of

values. Notice those method references:

1 public enum Gender implements ConvertedEnum<Integer> {

2 MALE(0, "mal"),

3 FEMALE(1, "fem"),

4 OTHER(-1, "oth");

5

6 private final Integer dbValue;

7 private final String code;

8

9 Gender(Integer dbValue, String code) {

10 this.dbValue = dbValue;

11 this.code = code;

12 }

13

14 @Override

15 public Integer toDbValue() {

16 return dbValue;

17 }

18

19 public String toCode() {

20 return code;

21 }

22

23 // static resolving:

24 public static final ReverseEnumResolver<Gender, Integer> resolver =

25 new ReverseEnumResolver<>(Gender.class, Gender::toDbValue);

26

27 public static Gender fromDbValue(Integer dbValue) {

28 return resolver.get(dbValue);

29 }

30

31 // static resolving to string:

32 public static final ReverseEnumResolver<Gender, String> strResolver =

33 new ReverseEnumResolver<>(Gender.class, Gender::toCode);

34

35 public static Gender fromCode(String code) {

36 return strResolver.get(code);

37 }

38 }

So this is how we can have two different values (dbValue and code) resolved with the same class

utilizing Java 8 method references.

If we wanted to store dbValue into one DB table and code into another table we would need two

different converters. At least one of them wouldn’t be able to utilize ConvertedEnum contract

anymore. Being on Java 8 I’d again use method references in converter subclass to specify both

conversion methods.

Let’s say our universal new AbstractAttributeConverter looks like this:

1 /** Base implementation for converting values in DB, not only for enums. */

2 public abstract class AbstractAttributeConverter<X, Y>

3 implements AttributeConverter<X, Y>

4 {

5 private final Function<X, Y> toDbFunction;

6 private final Function<Y, X> fromDbFunction;

7

8 public AbstractAttributeConverter(

9 Function<X, Y> toDbFunction, Function<Y, X> fromDbFunction)

10 {

11 this.toDbFunction = toDbFunction;

12 this.fromDbFunction = fromDbFunction;

13 }

14

15 @Override

16 public final Y convertToDatabaseColumn(X enumValue) {

17 return enumValue != null ? toDbFunction.apply(enumValue) : null;

18 }

19

20 @Override

21 public final X convertToEntityAttribute(Y dbValue) {

22 return dbValue != null ? fromDbFunction.apply(dbValue) : null;

23 }

24 }

Notice that I dropped previous notNull enforcing method because our reverse resolver does it

already (it still allows null values). The converter for Gender enum would be:

1 @Converter

2 public class GenderConverter extends AbstractAttributeConverter<Gender, Integer> {

3 public GenderConverterJava8() {

4 super(Gender::toDbValue, Gender::fromDbValue);

5 }

6 }

The only thing the abstract superclass does now (after dropping notNull) is that ternary

expression treating null values. So you may consider it overkill as of now. On the other hand

it prepares everything in such a way that concrete converter is really declarative and as concise

as possible (considering Java syntax). Also notice that we made ConvertedEnum obsolete.

In this last section we underlined how handy some Java 8 features can get. Method references allowed us to create more flexible reverse resolver which we can use for multiple mappings, it allowed us to declare concrete attribute converters in a super short manner where nothing is superfluous and we could get rid of contract interface for our enums.

Relational concerns

Mapping enumerated values from Java to DB is a more complex issue than just the conversion. The enumeration can be based on an existing dedicated table or it can exist exclusively in Java world. It may or may not change over time. All these factors play a role in how complicated things can get.

If DB is “just a store” and application is driving the design you may be happy with encoding

enums into a DB column as discussed throughout this chapter. But if we want to query the data

using meaningful values (like MALE instead of 0) or we want to get this meaningful description

into the outputs of SQL queries we’re asking for complications.

We may use enum names directly which is supported by JPA directly using EnumType.STRING but this

has a couple of disadvantages:

- It takes more space than necessary.

- In case we decide to rename the constant we have to synchronize it with the code deployment. Alternatively we can use converter to support both values in DB for some time – this may be necessary when we’re not able to rename the data quickly, e.g. there’s too much of it.

Actually, if we mention renaming in front of our DB admins they will want to put enum values into another table as it makes renaming a non-issue (at least from DB perspective). We use FK instead of the names. We can also use a single lookup table for all enum types or even more sophisticated meta-data facility. In every case it comes with a cost though and it virtually always violates DRY principle (don’t repeat yourself).

Often we are extending a legacy application where the DB schema is a given and we have to deal with its design. For some code list tables we may mirror the entries in an enum because it does not change that much (e.g. gender). This will save us a lot of troubles in the Java code, giving us all the power of enums. Other lists are not good candidates (e.g. countries or currencies) as they tend to change occasionally and are also much longer. These should be mapped normally as entities.

In this chapter we focused only on mapping enums to arbitrary values and back, but before mapping something that looks like an enumeration into the Java code always think twice whether Java enum is the best way. Especially if that enumeration has its own dedicated table.

13. Advanced Querydsl

At the beginning of the chapter dedicated to some of the more advanced points of Querydsl I’d like to reiterate that Querydsl has quite a good documentation. It’s not perfect and does not cover all the possibilities of the library – even in this chapter we will talk about some things that are not presented there. I tried to verify these not only by personal experience but also discussing some of them on the Querydsl Google Group. Other problems were solved thanks to StackOverflow, often thanks to answers from the authors of the library personally.

As mentioned in the first chapter about Querydsl you can find the description of a demonstration project in the appendix Project example. Virtually all code examples on GitHub for this book are based on that project layout so it should be easy to replicate.

Introducing handy utility classes

Most of the time using Querydsl we work with our generated Q-classes and JPAQuery class. There

are cases, however, when the fluent API is not enough and we need to add something else. This

typically happens in the where part and helps us putting predicates together, but there are

other cases too. Let’s quickly mention the classes we should know – our starting points for

various minor cases. Some of them will be just mentioned here, others will be discussed later in

this chapter.

-

ExpressionsandExpressionUtilsare probably the most useful classes allowing creation of variousExpressions. These may be functions (like current date) or variousPredicates (which isExpressionsubclass). -

JPADeleteClauseandJPAUpdateClause(both implementingDMLClause) are natural complement to our well-knownJPAQuerywhen we want to modify the data. -

BooleanBuildermutable predicate expression for buildingANDorORgroups from arbitrary number of predicates – discussed later in Groups of AND/OR predicates. -

GroupByBuilderis a fluent builder forGroupBytransformer instances. This class is not to be used directly, but viaGroupBy– see Result transformation. -

CaseBuilderand its special caseCaseForEqBuilder– not covered in this book but quite easy to use (see it in reference documentation). -

PathBuilderis an extension toEntityPathBasefor dynamic path construction.

Builders are to be instantiated to offer fluent API where it is not naturally available – like right after opening parenthesis. They don’t necessarily follow builder pattern as they often implement what they suppose to build and don’t require some final build method call. Other classes offer bunch of convenient static methods.

Tricky predicate parts

Writing static queries in Querydsl is nice but Querydsl is very strong beyond that. We can use

Querydsl expressions (implementations of com.querydsl.core.types.Expression) to create dynamic

predicates, or to define dynamic lists of returned columns. It’s easy to build your own “framework”

around these – easy and useful, as many of the problems occur again and again.

In a small project we may be satisfied with distinct code for various queries. Let’s say we have three screens with lists with couple of filtering criteria. There is hardly a need to invest into some universal framework. We simply have some base query and we just slap couple of conditions to it like so:

1 if (filter.getName() != null) {

2 query.where(d.name.eq(filter.getName()));

3 }

4 if (filter.getBirth() != null) {

5 query.where(d.birthdate.isNull()

6 .or(d.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now())));

7 }

Each where call adds another condition into an implicit top-level AND group. Condition for

birthdate will be enclosed in parenthesis to preserve the intended meaning.

You can toString the query (or just its where part, or any Querydsl expression for that matter),

this one will produce this output:

1 select dog

2 from Dog dog

3 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

But what if we have a project with many list/table views with configurable columns and filtering conditions for each column? This definitely calls for a framework of sort. We may still have predefined query objects but predicate construction should be unified. We may even drop query objects and have dynamic way how to add joins to a root entity. This, however, may be a considerable endeavour even though it may be well worth the effort in the end. My experiences in this area are quite extensive and I know that Querydsl will support you greatly.1

Groups of AND/OR predicates

Sometimes the structure of a filter gives us multiple values. If we try to find a dog with any

of provided names we can use single in, but often we have to create a predicate that joins

multiple conditions with or or and. How to do that?

If we want to code it ourselves, we can try something like (not a good version):

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGrouping(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 if (predicates.isEmpty()) {

3 return Expressions.TRUE; // no condition, accepting all

4 }

5

6 Predicate result = null;

7 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

8 if (result == null) {

9 result = predicate;

10 } else {

11 result = Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.OR, result, predicate);

12 }

13 }

14

15 return result;

16 }

The first thing to consider is what to return when the list is empty. If thrown into a where

clause TRUE seems to be neutral option – but only if combined with other predicates using AND.

If OR was used it would break the condition. However, Querydsl is smart enough to treat null

as neutral value so we can simply remove the first three lines:

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGrouping(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 Predicate result = null;

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 if (result == null) {

5 result = predicate;

6 } else {

7 result = Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.OR, result, predicate);

8 }

9 }

10

11 return result;

12 }

Try it in various queries and see that it does what you’d expect, with empty list not changing the condition.

Notice that we use Expressions.booleanOperation to construct the OR operation. Fluent or

is available on BooleanExpression but not on its supertype Predicate. You can use that subtype

but Expressions.booleanOperation will take care of it.

There is a shorter version using a loop:

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGroupingSimplified(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 Predicate result = null;

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 result = ExpressionUtils.or(result, predicate);

5 }

6 return result;

7 }

This utilizes ExpressionUtils.or which is extremely useful because – as you may guess from the

code – it treats null cases for us in a convenient way. This may not be a good way (and you can

use more strict Expressions.booleanOperation then) but here it’s exactly what we want.

Now this all seems to be working fine but we’re creating tree of immutable expressions and using

some expression utils “magic” in a process (good to learn and un-magic it if you are serious with

Querydsl). Because joining multiple predicates in AND or OR groups is so common there is a

dedicated tool for it – BooleanBuilder. Compared to what we know we don’t save that much:

1 private static Predicate buildOrGroup(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 BooleanBuilder bb = new BooleanBuilder();

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 bb.or(predicate);

5 }

6 return bb;

7 }

Good thing is that the builder also communicates our intention better. It actually uses

ExpressionUtils internally so we’re still creating all those objects behind the scene. If you

use this method in a fluent syntax you may rather return BooleanBuilder so you can chain other

calls on it.

However, in all the examples we used loop for something so trivial – collection of predicates coming in and we wanted to join them with simple boolean operation. Isn’t there even better way? Yes, there is:

1 Predicate orResult = ExpressionUtils.anyOf(predicates);

2 Predicate andResult = ExpressionUtils.allOf(predicates);

There are both collection and vararg versions so we’re pretty much covered. Other previously

mentioned constructs, especially BooleanBuilder are still useful for cases when the predicates

are created on the fly inside of a loop, but if we have predicates ready ExpressionUtils are

there for us.

Operator precedence and expression serialization

Let’s return to the first condition from this chapter as added if both ifs are executed. The

result was:

1 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

If we wanted to write the same condition in one go, fluently, how would we do it?

1 System.out.println("the same condition fluently (WRONG):\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex")

3 .and(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull())

4 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))));

Previous code produces result where AND would be evaluated first on the SQL level:

1 where dog.name = ?1 and dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2

We can easily fix this. We opened the parenthesis after and in the Java code

and we can nest the whole OR inside:

1 System.out.println("\nthe same condition fluently:\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex")

3 .and(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

4 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now())))));

This gives us what we expected again with OR grouped together.

1 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

Now imagine we wanted to write the OR group first:

1 System.out.println("\nthe same condition, different order:\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

3 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))

4 .and(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex"))));

This means we started our fluent predicate with an operator with a lower precedence. The result:

1 where (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?1) and dog.name = ?2

Wow! That went well – but you may as well wonder how? In the Java code it flows seemingly on the

same level, first OR then AND but the generated query didn’t put it on the same level. In the

previous example we could nest OR inside the AND on Java syntactic level (using parenthesis)

– but how does it work here?

The answer is actually pretty simple and it stems from Java syntax. If we add redundant parenthesis around OR it will be absolutely clear:

1 .where(

2 (QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

3 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))

4 ).and(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex"))));

Now we know what happened. As the calls are chained whatever before another call on the same level

is already grouped together as an expression. We can imagine the same parenthesis in the generated

JPQL as well, but if they are redundant they will be removed – this is the case when AND goes

first, but not the case when we start with OR. Parenthesis were added in the JPQL in order to

preserve the evaluation order.

In the following code all “expression-snakes” mean the same:

1 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4)

2 (e1.or(e2)).and(e3).or(e4)

3 ((e1.or(e2)).and(e3)).or(e4)

We just have to realize that the first one is not the same like SQL:

1 e1 OR e2 AND e3 OR e4

AND has the highest precedence and is evaluated first. In Querydsl it’s very easy to play with

expressions as you don’t need any entities at all and you don’t have to touch the database either

(don’t mind the BooleanTemplate, it’s just a kind of Querydsl Expression):

1 BooleanTemplate e1 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e1");

2 BooleanTemplate e2 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e2");

3 BooleanTemplate e3 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e3");

4 BooleanTemplate e4 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e4");

5 System.out.println("\ne1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = " +

6 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4));

7 System.out.println("\ne1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = " + new JPAQuery<>()

8 .where(e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4)));

This produces:

1 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = (e1 || e2) && e3 || e4

2

3 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = where (e1 or e2) and e3 or e4

The first line is not much SQL like but if we create just an empty query with where we will get

nice SQL-like result (although the whole query is obviously invalid). We see that the first OR

group is enclosed in parenthesis, just as we saw it in one of the examples before.

Finally, let’s try something even more complicated - let’s say we need:

1 ((e1 OR e2) AND (e3 OR e4)) OR (e5 AND e6)

For that we write this in Java:

1 .where(e1.or(e2).and(e3.or(e4)).or(e5.and(e6))))

Let’s check the output:

1 (e1 or e2) and (e3 or e4) or e5 and e6

Yup, it’s the one, unnecessary parenthesis around AND expressions are omitted but it will work.

Knowing this we can now write expressions confidently and visualize the resulting JPQL/SQL.

The bottom line is: Precedence as we know it from SQL does not matter – Java expression evaluation order does.

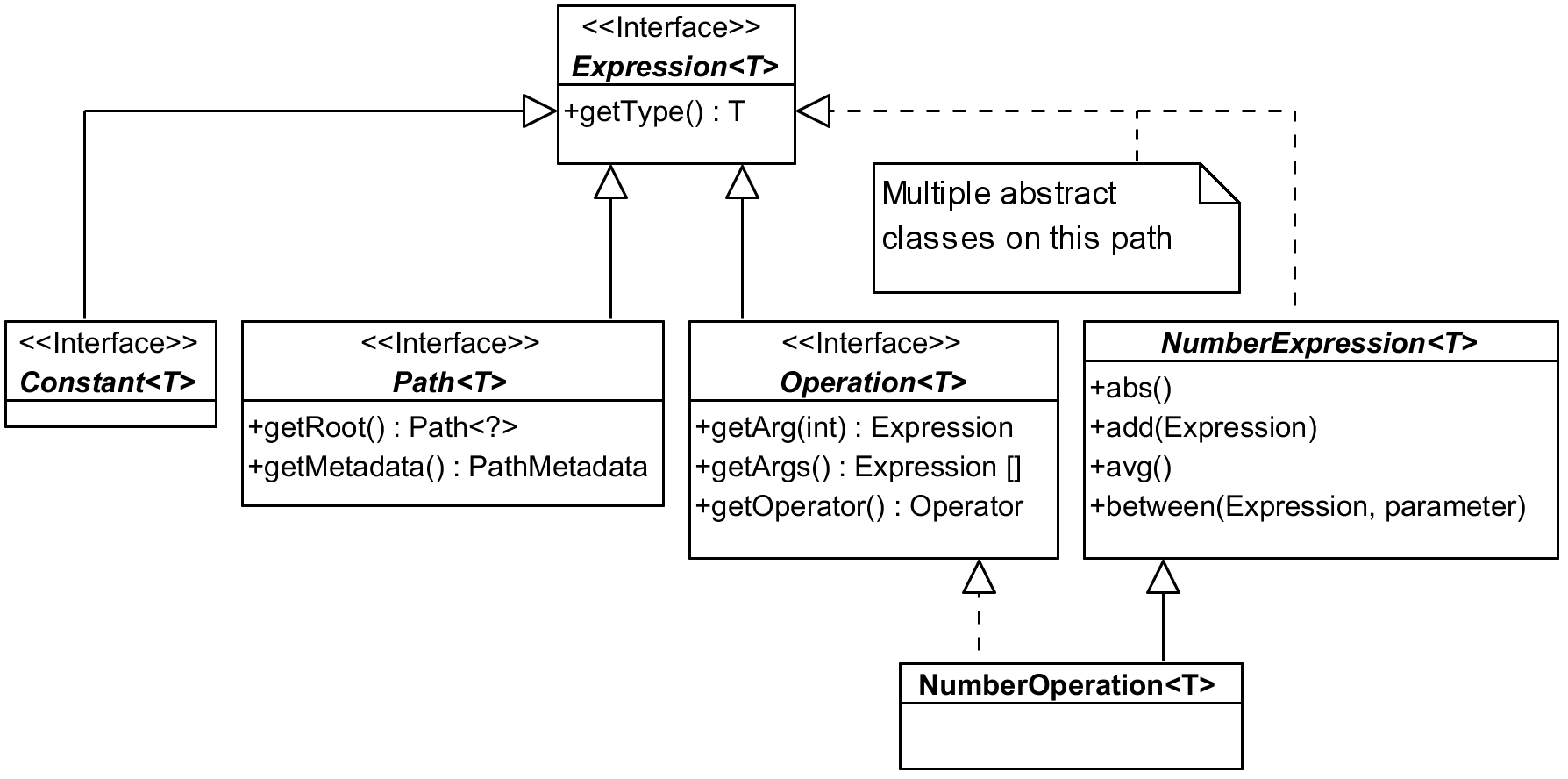

Querydsl Expression hierarchy

We talk about Expressions, Paths and Predicates a lot, but what is their relation? You may

guess there is some hierarchy involved and this one is a rich one, indeed. Let’s take a look at

the snippet of it from the top:

Most of the things we work with in Querydsl are somehow subtypes of Expression interface.

Picture shows just couple of examples – be it Constant used to wrap constants in expressions

like age.add(4) (here internally), or Path representing properties of our entity classes

(among other things), or Operation for results of combining other expressions with operators.

The list of direct sub-interfaces is longer, there are also three direct abstract sub-classes

that are another “path” how to get from concrete expression implementation to the top of this

hierarchy. In the picture above I used NumberOperation as an example. It implements Operation

interface, but also follows a longer path that adds a lot of expected methods to the type, here

from NumberExpression that has many more methods than listed in the picture.

Creators of Querydsl had to deal with both single class inheritance and general problems making

taxonomy trees and sometimes we can question whether they got it right, for instance: Isn’t number

constant a literal? Why doesn’t it extend LiteralExpression? Other times you expect some

operation on a common supertype but you find it defined in two separate branches of a hierarchy.

But these problems are expected in any complex hierarchy and designers must make some arbitrary

decisions. It’s not really difficult to find the proper solutions for our Querydsl problems.2

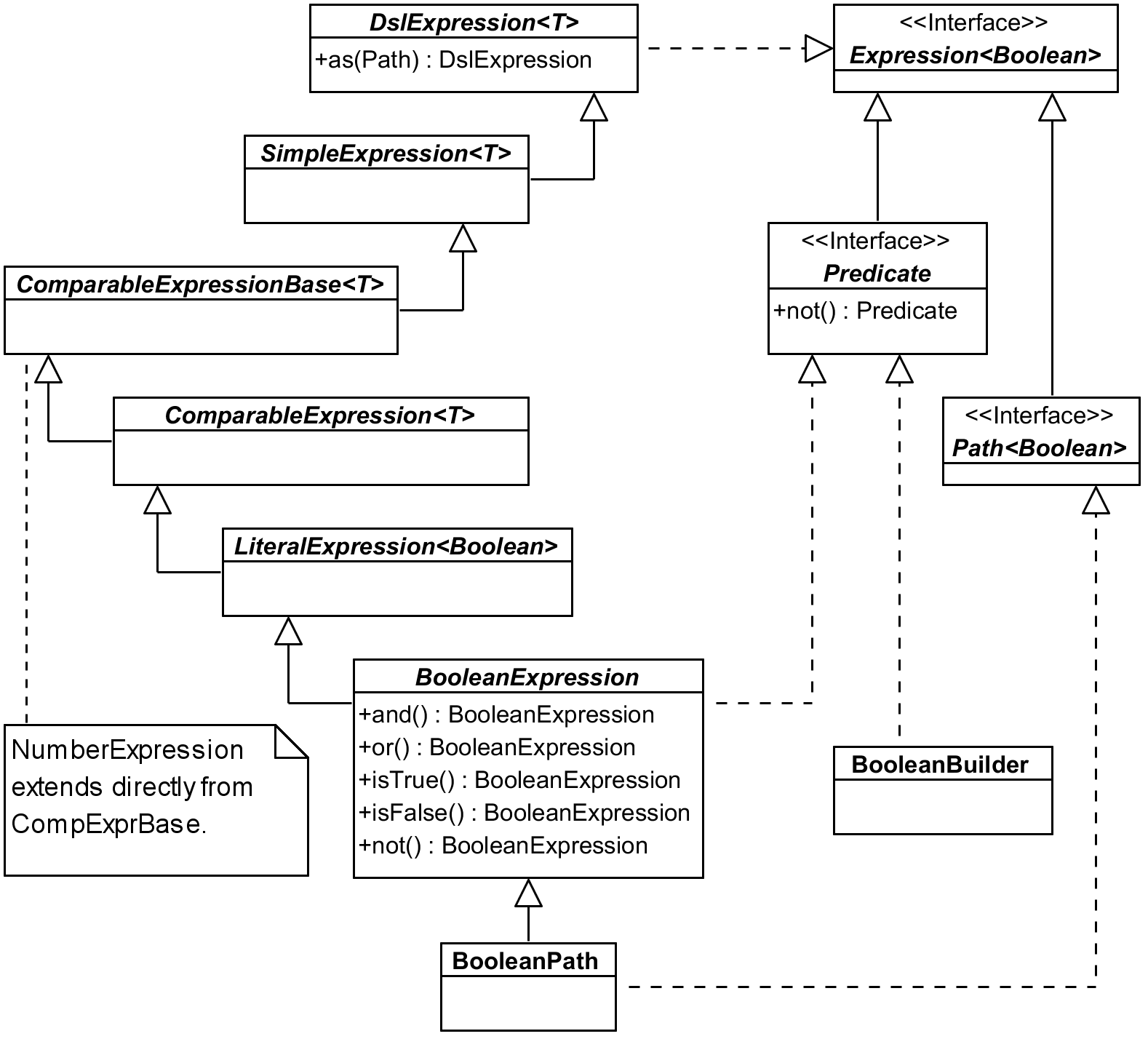

Let’s focus on another example of expression hierarchy, BooleanPath – this time from the bottom

to the top:

Here we followed the extends line all the way (any T is effectively Boolean).

BooleanExpression implements expected operations (I omitted andAnyOf(Predicate...) and

orAllOf(Predicate...) from the picture), any of those returning BooleanOperation which is also

a subclass of BooleanExpression.

LiteralExpression is a common supertype for other types of expressions StringExpression (and

StringPath and StringOperation), TemporalExpression with subtypes DateExpression,

TimeExpression and DateTimeExpression (and their paths), and EnumExpression. All these

subtypes having their Path and Operation implementations this part of the hierarchy seems to

be pretty regular and logical. (There are also Template implementations, but I don’t cover those

in the book.) LiteralExpression doesn’t add methods we would use that much, so let’s go one step

higher.

ComparableExpression adds tons of operation methods: between, notBetween, goe (greater or

equal), gt, loe and lt, the last four with ALL and ANY variants (e.g. goeAll). We will

get to the missing eq and similar higher in the hierarchy.

Let’s go to up to the ComparableExpressionBase which adds asc and desc methods returning

OrderSpecifier we use in the orderBy clause. It also contains coalesce method for SQL

function COALESCE returning first non-null argument. As the picture indicates this is also the

point where NumberExpression hierarchy starts (with NumberPath and NumberExpression) – it

does not sit at the same place like string, boolean and date/time expressions. It also implements

all the comparable functions (like gt) on its own which means that any infrastructure code for

comparing expressions has to have two separate branches. Never mind, let’s go up again.

SimpleExpression adds eq and ne (with ALL and ANY variants), isNull, isNotNull,

count, countDistinct, in, notIn, nullif and when for simple CASE cases with equals –

for more complicated cases you want to utilize more universal CaseBuilder.

Finally DslExpression gives us support for expression aliases using as method. (These are

different than aliases for joins we used until now.) Getting all the way up we now have all the

necessary methods we can use on BooleanPath – and the same applies for StringPath or, although

a bit sideways, for NumberPath and other expressions as well.

Constant expressions

When we start using expressions in a more advanced fashion (e.g. for the sake of some filtering

framework) we soon get to the need to convert constant (literal) to Querydsl Expression.

Consider a simple predicate like this:

1 QDog.dog.name.eq("Axiom")

Fluent API offers two options for the type of the parameter of eq (or similar operations).

String is most natural here and API knows it should be string because QDog.name is of type

StringPath – that is Path<String> which itself is Expression<String>. And

Expression<? super String> (not that String can have subtypes) is the second option we can use

as the type of the parameter for the eq method.

But when we try to use Expressions utilities to construct Operation we can only use expressions

and we need to convert any literal to the expression of a respective type – like this:

1 Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.EQ,

2 QDog.dog.name, Expressions.constant("Axiom"))

Equals being used quite often there is an alternative shortcut as well:

1 ExpressionUtils.eqConst(QDog.dog.name, "Axiom")

With this we can construct virtually any expression using Querydsl utility classes in a very flexible way.

Using FUNCTION template

JPA 2.1 allows us to call any function beyond the (quite limited) set of those supported by JPA specification – which is a nice extension point. Let’s see JPQL how to do that:

1 em.createQuery(

2 "select d.name, function('dayname', d.died) from Dog d ", Object[].class)

3 .getResultList()

4 .stream()

5 .map(Arrays::toString)

6 .forEach(System.out::println);

This may print (depending on the actual data):

1 [Lassie, Tuesday]

2 [Rex, null]

3 [Oracle, Wednesday]

Now how can we do the same with Querydsl? While it doesn’t provide this FUNCTION construct

directly it is very flexible with its templates. We already met BooleanTemplate in one of our

previous experiments, now let’s try to get this DAYNAME function working:

1 QDog d = QDog.dog;

2 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .from(d)

4 .select(d.name, dayname(d.died))

5 .fetch();

6 System.out.println("result = " + result);

7 // ...

8

9 private static StringTemplate dayname(Expression<LocalDate> date) {

10 return Expressions.stringTemplate("FUNCTION('dayname', {0})", date);

11 }