13. Advanced Querydsl

At the beginning of the chapter dedicated to some of the more advanced points of Querydsl I’d like to reiterate that Querydsl has quite a good documentation. It’s not perfect and does not cover all the possibilities of the library – even in this chapter we will talk about some things that are not presented there. I tried to verify these not only by personal experience but also discussing some of them on the Querydsl Google Group. Other problems were solved thanks to StackOverflow, often thanks to answers from the authors of the library personally.

As mentioned in the first chapter about Querydsl you can find the description of a demonstration project in the appendix Project example. Virtually all code examples on GitHub for this book are based on that project layout so it should be easy to replicate.

Introducing handy utility classes

Most of the time using Querydsl we work with our generated Q-classes and JPAQuery class. There

are cases, however, when the fluent API is not enough and we need to add something else. This

typically happens in the where part and helps us putting predicates together, but there are

other cases too. Let’s quickly mention the classes we should know – our starting points for

various minor cases. Some of them will be just mentioned here, others will be discussed later in

this chapter.

-

ExpressionsandExpressionUtilsare probably the most useful classes allowing creation of variousExpressions. These may be functions (like current date) or variousPredicates (which isExpressionsubclass). -

JPADeleteClauseandJPAUpdateClause(both implementingDMLClause) are natural complement to our well-knownJPAQuerywhen we want to modify the data. -

BooleanBuildermutable predicate expression for buildingANDorORgroups from arbitrary number of predicates – discussed later in Groups of AND/OR predicates. -

GroupByBuilderis a fluent builder forGroupBytransformer instances. This class is not to be used directly, but viaGroupBy– see Result transformation. -

CaseBuilderand its special caseCaseForEqBuilder– not covered in this book but quite easy to use (see it in reference documentation). -

PathBuilderis an extension toEntityPathBasefor dynamic path construction.

Builders are to be instantiated to offer fluent API where it is not naturally available – like right after opening parenthesis. They don’t necessarily follow builder pattern as they often implement what they suppose to build and don’t require some final build method call. Other classes offer bunch of convenient static methods.

Tricky predicate parts

Writing static queries in Querydsl is nice but Querydsl is very strong beyond that. We can use

Querydsl expressions (implementations of com.querydsl.core.types.Expression) to create dynamic

predicates, or to define dynamic lists of returned columns. It’s easy to build your own “framework”

around these – easy and useful, as many of the problems occur again and again.

In a small project we may be satisfied with distinct code for various queries. Let’s say we have three screens with lists with couple of filtering criteria. There is hardly a need to invest into some universal framework. We simply have some base query and we just slap couple of conditions to it like so:

1 if (filter.getName() != null) {

2 query.where(d.name.eq(filter.getName()));

3 }

4 if (filter.getBirth() != null) {

5 query.where(d.birthdate.isNull()

6 .or(d.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now())));

7 }

Each where call adds another condition into an implicit top-level AND group. Condition for

birthdate will be enclosed in parenthesis to preserve the intended meaning.

You can toString the query (or just its where part, or any Querydsl expression for that matter),

this one will produce this output:

1 select dog

2 from Dog dog

3 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

But what if we have a project with many list/table views with configurable columns and filtering conditions for each column? This definitely calls for a framework of sort. We may still have predefined query objects but predicate construction should be unified. We may even drop query objects and have dynamic way how to add joins to a root entity. This, however, may be a considerable endeavour even though it may be well worth the effort in the end. My experiences in this area are quite extensive and I know that Querydsl will support you greatly.1

Groups of AND/OR predicates

Sometimes the structure of a filter gives us multiple values. If we try to find a dog with any

of provided names we can use single in, but often we have to create a predicate that joins

multiple conditions with or or and. How to do that?

If we want to code it ourselves, we can try something like (not a good version):

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGrouping(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 if (predicates.isEmpty()) {

3 return Expressions.TRUE; // no condition, accepting all

4 }

5

6 Predicate result = null;

7 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

8 if (result == null) {

9 result = predicate;

10 } else {

11 result = Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.OR, result, predicate);

12 }

13 }

14

15 return result;

16 }

The first thing to consider is what to return when the list is empty. If thrown into a where

clause TRUE seems to be neutral option – but only if combined with other predicates using AND.

If OR was used it would break the condition. However, Querydsl is smart enough to treat null

as neutral value so we can simply remove the first three lines:

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGrouping(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 Predicate result = null;

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 if (result == null) {

5 result = predicate;

6 } else {

7 result = Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.OR, result, predicate);

8 }

9 }

10

11 return result;

12 }

Try it in various queries and see that it does what you’d expect, with empty list not changing the condition.

Notice that we use Expressions.booleanOperation to construct the OR operation. Fluent or

is available on BooleanExpression but not on its supertype Predicate. You can use that subtype

but Expressions.booleanOperation will take care of it.

There is a shorter version using a loop:

1 private static Predicate naiveOrGroupingSimplified(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 Predicate result = null;

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 result = ExpressionUtils.or(result, predicate);

5 }

6 return result;

7 }

This utilizes ExpressionUtils.or which is extremely useful because – as you may guess from the

code – it treats null cases for us in a convenient way. This may not be a good way (and you can

use more strict Expressions.booleanOperation then) but here it’s exactly what we want.

Now this all seems to be working fine but we’re creating tree of immutable expressions and using

some expression utils “magic” in a process (good to learn and un-magic it if you are serious with

Querydsl). Because joining multiple predicates in AND or OR groups is so common there is a

dedicated tool for it – BooleanBuilder. Compared to what we know we don’t save that much:

1 private static Predicate buildOrGroup(List<Predicate> predicates) {

2 BooleanBuilder bb = new BooleanBuilder();

3 for (Predicate predicate : predicates) {

4 bb.or(predicate);

5 }

6 return bb;

7 }

Good thing is that the builder also communicates our intention better. It actually uses

ExpressionUtils internally so we’re still creating all those objects behind the scene. If you

use this method in a fluent syntax you may rather return BooleanBuilder so you can chain other

calls on it.

However, in all the examples we used loop for something so trivial – collection of predicates coming in and we wanted to join them with simple boolean operation. Isn’t there even better way? Yes, there is:

1 Predicate orResult = ExpressionUtils.anyOf(predicates);

2 Predicate andResult = ExpressionUtils.allOf(predicates);

There are both collection and vararg versions so we’re pretty much covered. Other previously

mentioned constructs, especially BooleanBuilder are still useful for cases when the predicates

are created on the fly inside of a loop, but if we have predicates ready ExpressionUtils are

there for us.

Operator precedence and expression serialization

Let’s return to the first condition from this chapter as added if both ifs are executed. The

result was:

1 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

If we wanted to write the same condition in one go, fluently, how would we do it?

1 System.out.println("the same condition fluently (WRONG):\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex")

3 .and(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull())

4 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))));

Previous code produces result where AND would be evaluated first on the SQL level:

1 where dog.name = ?1 and dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2

We can easily fix this. We opened the parenthesis after and in the Java code

and we can nest the whole OR inside:

1 System.out.println("\nthe same condition fluently:\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex")

3 .and(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

4 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now())))));

This gives us what we expected again with OR grouped together.

1 where dog.name = ?1 and (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?2)

Now imagine we wanted to write the OR group first:

1 System.out.println("\nthe same condition, different order:\n" + dogQuery()

2 .where(QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

3 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))

4 .and(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex"))));

This means we started our fluent predicate with an operator with a lower precedence. The result:

1 where (dog.birthdate is null or dog.birthdate >= ?1) and dog.name = ?2

Wow! That went well – but you may as well wonder how? In the Java code it flows seemingly on the

same level, first OR then AND but the generated query didn’t put it on the same level. In the

previous example we could nest OR inside the AND on Java syntactic level (using parenthesis)

– but how does it work here?

The answer is actually pretty simple and it stems from Java syntax. If we add redundant parenthesis around OR it will be absolutely clear:

1 .where(

2 (QDog.dog.birthdate.isNull()

3 .or(QDog.dog.birthdate.goe(LocalDate.now()))

4 ).and(QDog.dog.name.eq("Rex"))));

Now we know what happened. As the calls are chained whatever before another call on the same level

is already grouped together as an expression. We can imagine the same parenthesis in the generated

JPQL as well, but if they are redundant they will be removed – this is the case when AND goes

first, but not the case when we start with OR. Parenthesis were added in the JPQL in order to

preserve the evaluation order.

In the following code all “expression-snakes” mean the same:

1 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4)

2 (e1.or(e2)).and(e3).or(e4)

3 ((e1.or(e2)).and(e3)).or(e4)

We just have to realize that the first one is not the same like SQL:

1 e1 OR e2 AND e3 OR e4

AND has the highest precedence and is evaluated first. In Querydsl it’s very easy to play with

expressions as you don’t need any entities at all and you don’t have to touch the database either

(don’t mind the BooleanTemplate, it’s just a kind of Querydsl Expression):

1 BooleanTemplate e1 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e1");

2 BooleanTemplate e2 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e2");

3 BooleanTemplate e3 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e3");

4 BooleanTemplate e4 = Expressions.booleanTemplate("e4");

5 System.out.println("\ne1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = " +

6 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4));

7 System.out.println("\ne1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = " + new JPAQuery<>()

8 .where(e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4)));

This produces:

1 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = (e1 || e2) && e3 || e4

2

3 e1.or(e2).and(e3).or(e4) = where (e1 or e2) and e3 or e4

The first line is not much SQL like but if we create just an empty query with where we will get

nice SQL-like result (although the whole query is obviously invalid). We see that the first OR

group is enclosed in parenthesis, just as we saw it in one of the examples before.

Finally, let’s try something even more complicated - let’s say we need:

1 ((e1 OR e2) AND (e3 OR e4)) OR (e5 AND e6)

For that we write this in Java:

1 .where(e1.or(e2).and(e3.or(e4)).or(e5.and(e6))))

Let’s check the output:

1 (e1 or e2) and (e3 or e4) or e5 and e6

Yup, it’s the one, unnecessary parenthesis around AND expressions are omitted but it will work.

Knowing this we can now write expressions confidently and visualize the resulting JPQL/SQL.

The bottom line is: Precedence as we know it from SQL does not matter – Java expression evaluation order does.

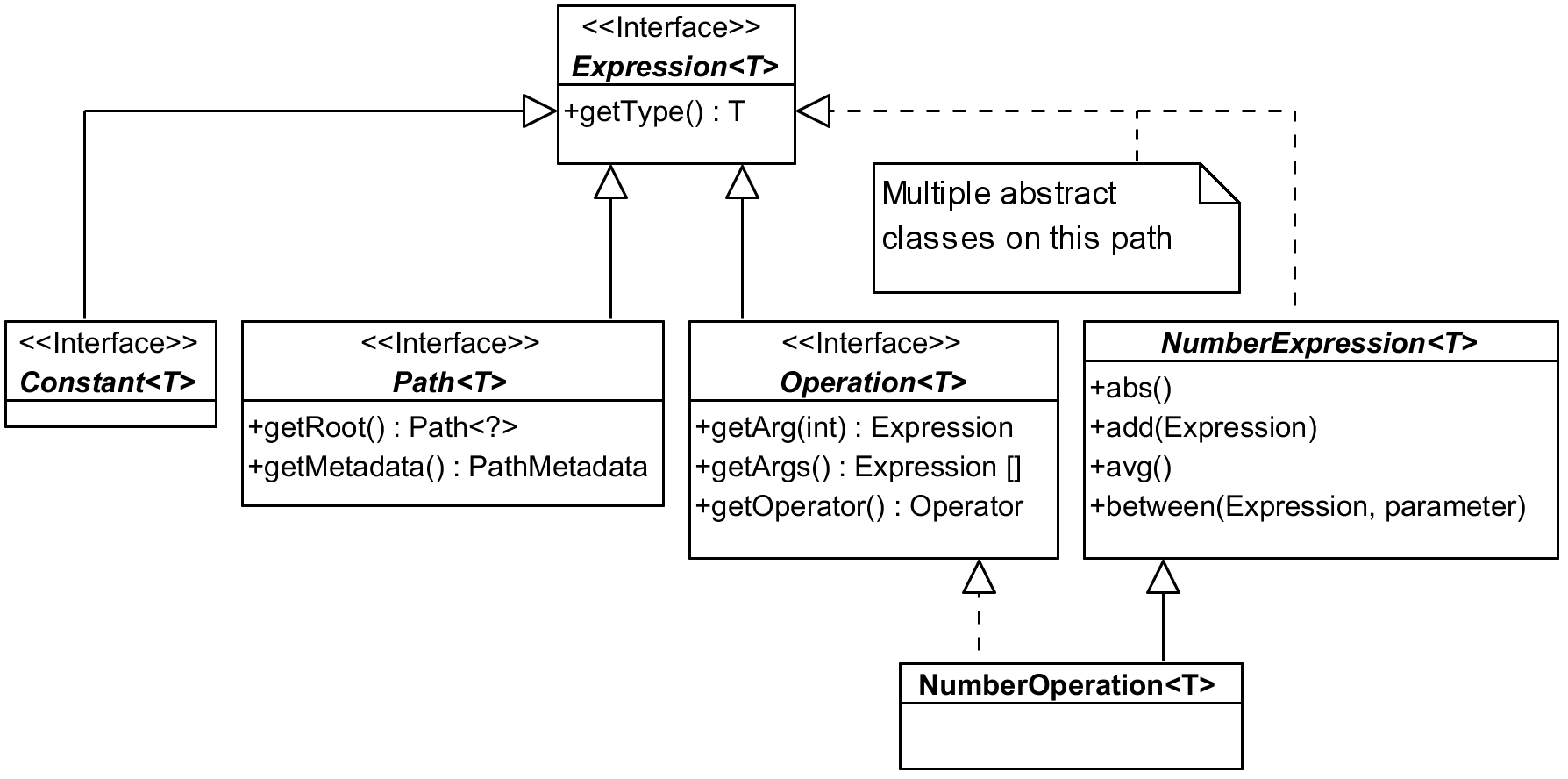

Querydsl Expression hierarchy

We talk about Expressions, Paths and Predicates a lot, but what is their relation? You may

guess there is some hierarchy involved and this one is a rich one, indeed. Let’s take a look at

the snippet of it from the top:

Most of the things we work with in Querydsl are somehow subtypes of Expression interface.

Picture shows just couple of examples – be it Constant used to wrap constants in expressions

like age.add(4) (here internally), or Path representing properties of our entity classes

(among other things), or Operation for results of combining other expressions with operators.

The list of direct sub-interfaces is longer, there are also three direct abstract sub-classes

that are another “path” how to get from concrete expression implementation to the top of this

hierarchy. In the picture above I used NumberOperation as an example. It implements Operation

interface, but also follows a longer path that adds a lot of expected methods to the type, here

from NumberExpression that has many more methods than listed in the picture.

Creators of Querydsl had to deal with both single class inheritance and general problems making

taxonomy trees and sometimes we can question whether they got it right, for instance: Isn’t number

constant a literal? Why doesn’t it extend LiteralExpression? Other times you expect some

operation on a common supertype but you find it defined in two separate branches of a hierarchy.

But these problems are expected in any complex hierarchy and designers must make some arbitrary

decisions. It’s not really difficult to find the proper solutions for our Querydsl problems.2

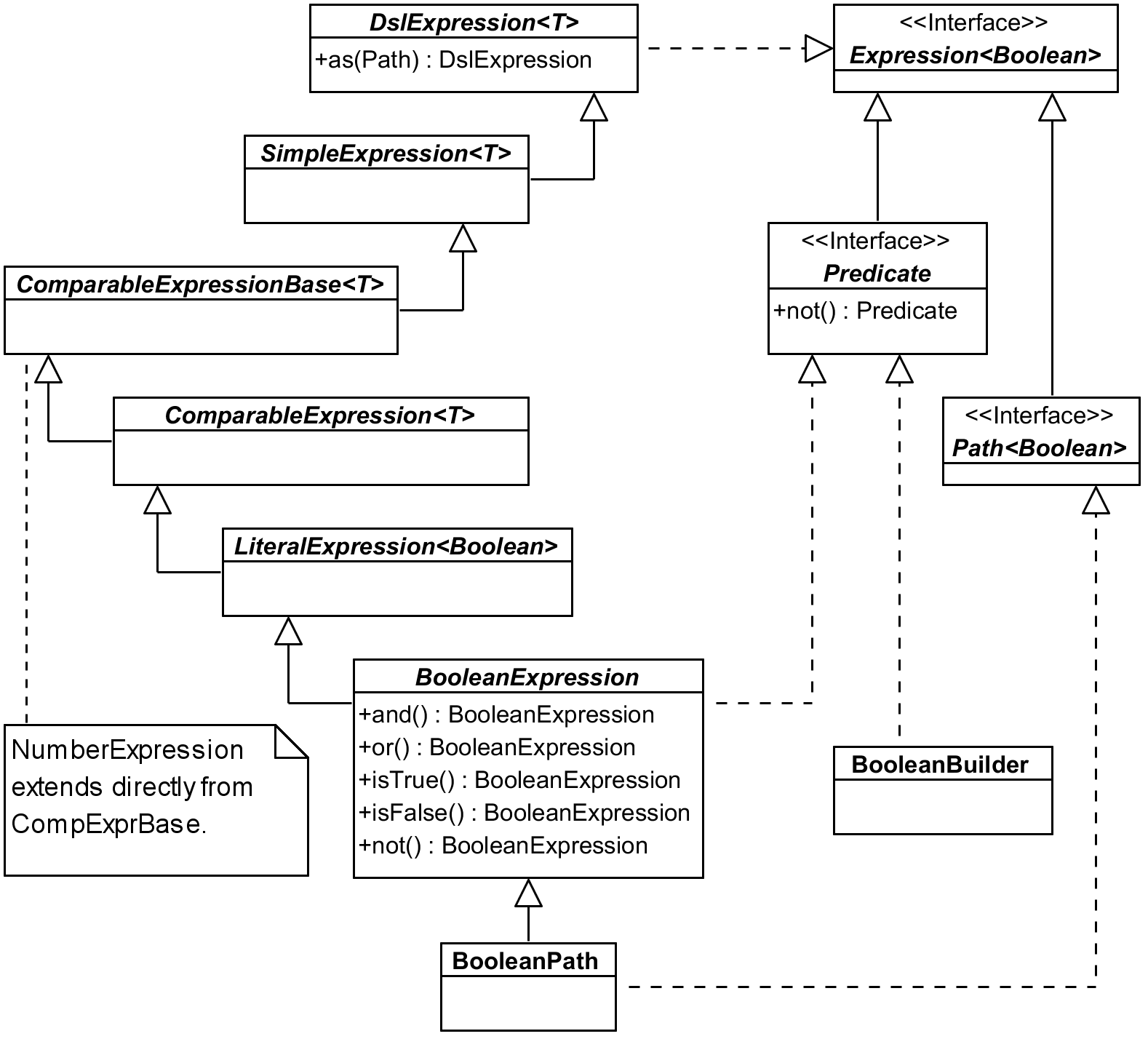

Let’s focus on another example of expression hierarchy, BooleanPath – this time from the bottom

to the top:

Here we followed the extends line all the way (any T is effectively Boolean).

BooleanExpression implements expected operations (I omitted andAnyOf(Predicate...) and

orAllOf(Predicate...) from the picture), any of those returning BooleanOperation which is also

a subclass of BooleanExpression.

LiteralExpression is a common supertype for other types of expressions StringExpression (and

StringPath and StringOperation), TemporalExpression with subtypes DateExpression,

TimeExpression and DateTimeExpression (and their paths), and EnumExpression. All these

subtypes having their Path and Operation implementations this part of the hierarchy seems to

be pretty regular and logical. (There are also Template implementations, but I don’t cover those

in the book.) LiteralExpression doesn’t add methods we would use that much, so let’s go one step

higher.

ComparableExpression adds tons of operation methods: between, notBetween, goe (greater or

equal), gt, loe and lt, the last four with ALL and ANY variants (e.g. goeAll). We will

get to the missing eq and similar higher in the hierarchy.

Let’s go to up to the ComparableExpressionBase which adds asc and desc methods returning

OrderSpecifier we use in the orderBy clause. It also contains coalesce method for SQL

function COALESCE returning first non-null argument. As the picture indicates this is also the

point where NumberExpression hierarchy starts (with NumberPath and NumberExpression) – it

does not sit at the same place like string, boolean and date/time expressions. It also implements

all the comparable functions (like gt) on its own which means that any infrastructure code for

comparing expressions has to have two separate branches. Never mind, let’s go up again.

SimpleExpression adds eq and ne (with ALL and ANY variants), isNull, isNotNull,

count, countDistinct, in, notIn, nullif and when for simple CASE cases with equals –

for more complicated cases you want to utilize more universal CaseBuilder.

Finally DslExpression gives us support for expression aliases using as method. (These are

different than aliases for joins we used until now.) Getting all the way up we now have all the

necessary methods we can use on BooleanPath – and the same applies for StringPath or, although

a bit sideways, for NumberPath and other expressions as well.

Constant expressions

When we start using expressions in a more advanced fashion (e.g. for the sake of some filtering

framework) we soon get to the need to convert constant (literal) to Querydsl Expression.

Consider a simple predicate like this:

1 QDog.dog.name.eq("Axiom")

Fluent API offers two options for the type of the parameter of eq (or similar operations).

String is most natural here and API knows it should be string because QDog.name is of type

StringPath – that is Path<String> which itself is Expression<String>. And

Expression<? super String> (not that String can have subtypes) is the second option we can use

as the type of the parameter for the eq method.

But when we try to use Expressions utilities to construct Operation we can only use expressions

and we need to convert any literal to the expression of a respective type – like this:

1 Expressions.booleanOperation(Ops.EQ,

2 QDog.dog.name, Expressions.constant("Axiom"))

Equals being used quite often there is an alternative shortcut as well:

1 ExpressionUtils.eqConst(QDog.dog.name, "Axiom")

With this we can construct virtually any expression using Querydsl utility classes in a very flexible way.

Using FUNCTION template

JPA 2.1 allows us to call any function beyond the (quite limited) set of those supported by JPA specification – which is a nice extension point. Let’s see JPQL how to do that:

1 em.createQuery(

2 "select d.name, function('dayname', d.died) from Dog d ", Object[].class)

3 .getResultList()

4 .stream()

5 .map(Arrays::toString)

6 .forEach(System.out::println);

This may print (depending on the actual data):

1 [Lassie, Tuesday]

2 [Rex, null]

3 [Oracle, Wednesday]

Now how can we do the same with Querydsl? While it doesn’t provide this FUNCTION construct

directly it is very flexible with its templates. We already met BooleanTemplate in one of our

previous experiments, now let’s try to get this DAYNAME function working:

1 QDog d = QDog.dog;

2 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .from(d)

4 .select(d.name, dayname(d.died))

5 .fetch();

6 System.out.println("result = " + result);

7 // ...

8

9 private static StringTemplate dayname(Expression<LocalDate> date) {

10 return Expressions.stringTemplate("FUNCTION('dayname', {0})", date);

11 }

Of course, Expressions.stringTemplate can be inlined, but we made it reusable this way. Parameters

following the template string are either Object... vararg or List<?>. This is flexible enough

but raises the question whether we want to be type-safe on the level of our method call or not. If

I chose Object for date parameter (or even more universal Object...) I could freely call it

with a java.util.Date literal as well (not LocalDate as H2 database does not support these

directly).

Type of the template – which happens to be some subtype of TemplateExpression – can be anything.

The most common types of templates are easy to create using specific methods on Expressions –

like stringTemplate or dateTemplate – and then there is template (or simpleTemplate) where

we can specify the type parameter as a first argument.

Using it in a query itself is then very easy as demonstrated above.

Update/delete clauses and exception handling

Very often we need some common exceptional handling for insert/update/delete clauses – especially

for the cases of constraint violations. We achieve this with some common BaseDao (also known as

layer supertype). It’s easy to have

a single common persist method, but we often need various specific update/delete clauses (these

are the parts that bypass the persistence context to a degree).

So instead of a block like this (which would have to be wrapped in a try/catch and the exception handling would be repeated over and over):

1 // delete by holidays by calendar ID

2 new JPADeleteClause(entityManager, $)

3 .where($.calendarId.eq(calendar.getId()))

4 .execute();

We use this with exception handling hidden inside the call:

1 execute(deleteFrom($)

2 .where($.calendarId.eq(calendar.getId())));

This requires us to introduce the following methods in our common BaseDao:

1 protected final JPADeleteClause deleteFrom(EntityPath<?> path) {

2 return new JPADeleteClause(entityManager, path);

3 }

4

5 protected long execute(DMLClause dmlClause) {

6 try {

7 return dmlClause.execute();

8 } catch (PersistenceException e) {

9 throw convertPersistenceException(e);

10 }

11 }

This is just an example and we don’t have to use common layer supertype, but we definitely want to

put the common exception handling on a single place. I didn’t present JPAUpdateClause in this

section but the need for common exception handling relates to it as well, of course.

JPAQueryFactory

Querydsl reference documentation, part about querying JPA states:

Personally I’ve been using JPAQuery directly for ages and never missed the factory, but there are

some minor advantages:

-

JPAQueryFactorycan be pre-created once per managed component with thread-safe persistence context (EntityManagerthat is). This also means that in non-managed context we perhaps don’t use it that much. - If we need to customize

JPQLTemplateswe don’t have to repeat it every time we create the query but only when we create theJPAQueryFactory. - Factory has also handy combo methods like

selectFromand other convenient shortcuts.

Other than this it doesn’t really matter. Looking at the implementation the factory is so

lightweight that if you want to use something like selectFrom you may create it even if it’s

short-lived. But you’re perfectly fine without it as well without missing anything crucial.

In the end we typically implement some “mini-framework” in our data layer superclass anyway. It may use the factory or not and still offer any convenient methods for query creation and more.

Detached queries

Typically we create the JPAQuery with EntityManager parameter, but sometimes it feels more

natural to put queries into a constant a reuse them later – something resembling named queries

facility of JPA. This is possible using so called “detached queries” – simply create a query

without entity manager and later clone it with entity manager provided:

1 private static QDog DOG_ALIAS = new QDog("d1");

2 private static Param<String> DOG_NAME_PREFIX =

3 new Param<String>(String.class);

4 private static JPAQuery<Dog> DOG_QUERY = new JPAQuery<>()

5 .select(DOG_ALIAS)

6 .from(DOG_ALIAS)

7 .where(DOG_ALIAS.name.startsWith(DOG_NAME_PREFIX));

8

9 //... and somewhere in a method

10 List<Dog> dogs = DOG_QUERY.clone(em)

11 .set(DOG_NAME_PREFIX, "Re")

12 .fetch();

The benefit is questionable though. We need to name the query well enough so it expresses what

it does while seeing the query sometimes says it better. We have to walk the distance to introduce

parameter constants and use them explicitly after the clone. There is also probably hardly-if-any

performance benefit because cloning and creating a query from the scratch are essentially the same

activity.

Perhaps there are legitimate cases when to use this feature, but I personally used it only in query objects wrapping complicated query where I have a lot of aliases around already – and even then mostly without the where part which I rather add dynamically later. But the same can be achieved by a method call – preferably placed in a designated query object:

1 public class DogQuery {

2 private static QDog DOG_ALIAS = new QDog("d1");

3

4 private final EntityManager em;

5

6 public DogQuery(EntityManager em) {

7 this.em = em;

8 }

9

10 public JPAQuery<Dog> query() {

11 return new JPAQuery<>(em)

12 .select(DOG_ALIAS)

13 .from(DOG_ALIAS);

14 }

15

16 public JPAQuery<Dog> nameStartsWith(String namePrefix) {

17 return query()

18 .where(DOG_ALIAS.name.startsWith(namePrefix));

19 }

20 }

First method query does not have to be exposed but often it comes handy, next one produces the

query from the previous example. To use it we need EntityManager, just like we needed it in the

clone example above.

1 List<Dog> dogs = new DogQuery(em)

2 .nameStartsWith("Re")

3 .fetch();

We can use builder pattern if we want to, many options open up when the query has a place to live.

Working with dates and java.time API

Because Querydsl 4.x still supports Java before version 8 it does not have native support for

new date/time types. But with JPA we can use any other type that can capture date and time

information, so technically Querydsl should be prepared for any class to represent date/time.

This is achieved by DateTimeExpression being parametrized type which covers our needs as long

as the class we use implements Comparable.

Then there are static methods on the DateTimeExpression representing SQL functions like

current_date. These by default return expression parametrized to Date, but we can specific

the requested date/time type using additional Class parameter:

1 QDog d = QDog.dog;

2 List<Dog> liveDogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(d)

4 .from(d)

5 // client-side option - no problem there with generics

6 //.where(d.birthdate.before(LocalDate.now()))

7 //.where(d.died.after(LocalDate.now()).or(d.died.isNull()))

8

9 // using function on the database side

10 .where(d.birthdate.before(DateExpression.currentDate(LocalDate.class))

11 .and(d.died.after(DateExpression.currentDate(LocalDate.class))

12 .or(d.died.isNull())))

13 .fetch();

Alas, even with Querydsl having us covered there can still be striking problems with the support

of Java 8 types (or other converted types) in concrete JPA implementations. For instance,

EclipseLink ignores date/time converters in coalesce.

To mix dates with timestamps we might need to use custom functions described earlier. In general JPA does not support much of temporal arithmetic.

Result transformation

We already know how to select an entity or a single attribute (column) or tuples of entities and/or

attributes (columns). We also saw some groupBy examples previously. But very often we want to

get a Map instead of List. For instance, instance of this:

1 List<Tuple> tuple = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.id.count())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .groupBy(QDog.dog.name)

5 .fetch();

6 System.out.println("name and count (as list, not map) = " + tuple);

We would prefer this:

1 Map<String, Long> countByName = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .from(QDog.dog)

3 .groupBy(QDog.dog.name)

4 .transform(groupBy(QDog.dog.name).as(QDog.dog.id.count()));

5 System.out.println("countByName = " + countByName);

Couple of things are clear from the code:

- We don’t need

selectas it is implied bytransformarguments and called internally. - There is also no need to call explicit

fetch–transformis a terminal operation and calls it internally.

Method groupBy is statically imported from provided GroupBy class. You can return list of

multiple results in as part and you can use aggregation functions like sum, avg, etc.

Transform itself does not affect generated query, it only post-process its results. It is in no way

tied to groupBy call, although they often come together. Very often it is used to get a map of

something unique to the values. We can, for instance, map IDs to their entities (Map of entities

with ID as a key) or IDs to a particular attribute:

1 Map<Integer, Dog> breedsById = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .from(QDog.dog)

3 .transform(groupBy(QDog.dog.id).as(QDog.dog));

4 System.out.println("breedsById = " + breedsById);

I personally miss simple list and map terminal operations from Querydsl 3 which leads us to

a final part of this chapter.

Note about Querydsl 3 versus 4

I’ve used major versions 2 and 3 in my projects and started to use version 4 only when I started to write this book. After initial investigation I realized that I’ll hardly switch from version 3 to version 4 in any reasonably sized project easily. Other thing is whether I even want. I don’t want to let version 4 down, it does a lot to get the DSL closer to SQL semantics – but that’s the question: Is it really necessary?

Let’s compare a query from version 4 with the same query from version 3 – let’s start with 4:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.name.like("Re%"))

5 .fetch();

Next example shows the same in Querydsl version 3:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery(em)

2 .from(QDog.dog)

3 .where(QDog.dog.name.like("Re%"))

4 .list(QDog.dog);

Personally I like the latter more even though the first one is more SQL-like notation. Version 3

is one line shorter – that purely technical fetch() call is pure noise. Further that fetch()

was used in version 3 to declare fetching of the joined entity, in version 4 you have to use

fetchAll() for that. This means that fetch*() methods are not part of one family – that’s

far from ideal from API/DSL point of view.

Convenient map is gone

In Querydsl 3 you could also use handy map(key, value) method instead of list – and it

returned Map exactly as you’d expect:

1 Map<Integer, Dog> dogsById = new JPAQuery(em)

2 .from(QDog.dog)

3 .map(QDog.dog.id, QDog.dog);

In Querydsl 4 you are left with something more abstract, more elusive and definitely more talkative:

1 Map<Integer, Dog> breedsById = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .from(QDog.dog)

3 .transform(groupBy(QDog.dog.id).as(QDog.dog));

Solution with transform is available in Querydsl 3 as well and covers also cases map does not

(see previous section on result transformation). You don’t need

select here because transform specifies what to return and you don’t need fetch either

as it works as a terminal operation – just like list in version 3. So in order to get a list

you have to use different flow of the fluent API than for a map.

Placement of select

As for the fluency, most programmers in our team agreed to prefer finishing with the

list(expressions...) call as the last call clearly says what gets returned. With SQL-like

approach you do this first, then add various JOINs – but this all goes against typical Java-like

programming mindset. For me personally version 3 hit the sweet spot perfectly – it gave me very

SQL-like style of queries to a degree I needed and the terminal operation (e.g. list) perfectly

expressed what I want to return without any superfluous dangling fetch.

We can also question what changes more. Sometimes we change the list of expressions, which means

we have to construct the whole query again and the most moving part – the list of resulting

expressions – goes right at the start. I cannot have my query

template with FROM and JOINs ready anymore. All I had to do before was to clone it (so we don’t

change the template), add where parts based on some filter and declare what expressions we want

as results, based on well-known available aliases, columns, etc.

Sure you have to have all the JOIN aliases thought out before anyway, so it’s not such a big deal

to create all the queries dynamically and add JOINs after you “use them” in the SELECT part,

because the aliases are the common ground and probably available as some constants. But there is

another good scenario for pre-created template query – you can inspect its metadata and do some

preparation based on this.

We used this for our filter framework where the guys from UI know exactly what kind of aliases we

offer, because we crate a Map<String, SimpleExpression<?>> to get to the paths representing the

alias by its name very quickly. We can still do this with Querydsl 4. We create one query selecting

the entity used in the FROM clause (makes sense) and extract the map of aliases on this one,

discarding this “probe query” afterwards. Not a big deal, but still supports the idea that after

the WHERE clause it is the SELECT part that is most flexible and using it right at the start

of the “sentence” may sound natural, but not programmatically right.

Rather accidentally we found out that in Querydsl 4 we actually can move select to the end and

finish with select(...).fetch(). The fetch here looks even more superfluous than before, but

the question is whether we want to use both styles in one project. With Querydsl 3 this question

was never raised.

Subqueries

In Querydsl 3 we used JPASubQuery for subqueries – in Querydsl 4 we use ordinary JPAQuery,

we just don’t provide it with entity manager and we don’t use terminal operations like fetch

that would trigger it immediately. This change is not substantial from developer’s perspective,

either of this works without problems.