7. No further step without Querydsl

I do realize I’m breaking a flow of the book a little bit, but since I’ve been introduced to this neat library I became a huge fan and I never looked back. It doesn’t affect JPA itself because it sits above it but in your code it virtually replaces both JPQL and especially Criteria API.

To put it simply, Querydsl is a library that – from programmer’s perspective – works like a more expressive and readable version of Java Persistence Criteria API. Internally it first generates JPQL and the rest from there is handled by the JPA provider. Querydsl can actually talk to many more back-ends: SQL, Hibernate directly and others, but we will focus on Querydsl over JPA here. To use it goes in these steps:

- declare the dependency for Querydsl library and to its annotation processor,

- add a step in your build to generate metamodel classes,

- and write queries happily in sort of criteria-like way.

But Criteria API also lets you use generated metamodel, so what’s the deal? Why would I introduce non-standard third-party library when it does not provide any additional advantage? If you even hate this idea, then you probably can stop reading this book – or you can translate all my Querydsl code into JPQL or Criteria yourself, which is perfectly doable, of course! Querydsl does not disrupt the stack under it, it is “just” slapped over the JPA to make it more convenient.

Querydsl brings in a domain-specific language (DSL) in the form of its fluent API. It happens to be so-called internal DSL because it’s still embedded in Java, it’s not different language per se. This fluent API is more concise, readable and convenient than Criteria API.

DSL is a language of some specific domain – in this case it’s a query language very close to JPQL or SQL. It builds on a generated metamodel a lot. API of this metamodel is well-though and takes type-safety to a higher level compared with Criteria API. This not only gives us compile-time checks for our queries, but also offers even better auto-completion in IDEs.

Simple example with Querydsl

Let’s be concrete now – but also very simple. We have a class Dog, each dog has a name

and we will query by this name. Assuming we got hold of EntityManager (variable em) the code

goes like this:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.name.like("Re%"))

5 //.where(QDog.dog.name.startsWith("Re")) // alternative

6 .fetch();

Both where alternatives produce the same result in this case, but startsWith may communicate

the intention better, unless you go for like("%any%") in which case contains would be better.

If you are provided input values for like, leave it. If you can tell from the logic that more

specific name for the operation is better, go for it.

This is a very subtle thing, but we can see that this DSL contains variations that can communicate

our intention more clearly. Criteria API sticks to like only, because that is its internal model.

Other thing is how beautifully the whole query flows. In version 4.x the fluent API got even closer

to JPQL/SQL semantics, it starts with select (what) and ends with fetch which is a mere

signal to deliver the results. As with any other fluent API, you need a terminal operation.

In previous versions you would have no select because it was included in a terminal operation,

e.g. list(QDog.dog). Newer version is one line longer, but closer to the target domain

of query languages. Advanced chapter has a dedicated section on differences between

versions 3 and 4.

Comparison with Criteria API

Both Querydsl and Criteria API are natural fit for dynamic query creation. Doing this with JPQL

is rather painful. Imagine a search form with separate fields for a person

entity, so you can search by name, address, date of birth from–to, etc. We don’t want to add

the search condition when the respective input field is empty. If you have done this before

with any form of query string concatenation then you probably know the pain. In extreme cases

of plain JDBC with prepared statement you even have to write all the ifs twice – first to add

where condition (or and for any next one) and second to set parameters. Technically you can

embed the parameter values into the query, but let’s help the infamous

injection vulnerability get off the top of the

OWASP Top 10 list.

Let’s see how query for our dogs looks like with Criteria API – again starting from em:

1 CriteriaBuilder cb = em.getCriteriaBuilder();

2 CriteriaQuery<Dog> query = cb.createQuery(Dog.class);

3 Root<Dog> dog = query.from(Dog.class);

4 query.select(dog)

5 // this is the only place where we can use metamodel in this example

6 .where(cb.like(dog.get(Dog_.name), "Re%"));

7 // without metamodel it would be:

8 //.where(cb.like(dog.<String>get("name"), "Re%"));

9 List<Dog> dogs = em.createQuery(query)

10 .getResultList();

Let’s observe now:

- First you need to get

CriteriaBuilderfrom existingem. You might “cache” this into a field but it may not play well with EE component model, so I’d rather get it before using. This should not be heavy operation, in most cases entity manager holds this builder already and merely gives it to you (hencegetand notneworcreate). - Then you create an instance of

CriteriaQuery. - From this you need to get a

Rootobject representing content of afromclause. - Then you use the

queryin a nearly-fluent fashion. Version with metamodel is presented with alternative without it in the comment. - Finally, you use

emagain to get aTypedQuerybased on theCriteriaQueryand we ask it for results.

While in case of Criteria API you don’t need to generate metamodel from the entity classes, in Querydsl this is not optional. But using metamodel in Criteria API is advantageous anyway so the need to generate the metamodel for Querydsl using annotation processor can hardly be considered a drawback. It can be easily integrated with Maven or other build as demonstrated in the companion sources to this book or documented on Querydsl site.

For another comparison of Querydsl and Criteria API, you can also check the original blog post from 2010. Querydsl was much younger then (version 1.x) but the difference was striking already.

Comparison with JPQL

Comparing Querydsl with Criteria API was rather easy as they are in the same ballpark. Querydsl, however, with its fluency can be compared to JPQL as well. After all JPQL is non-Java DSL, even though it typically is embedded in Java code. Let’s see JPQL in action first to finish our side-by-side comparisons:

1 List<Dog> dogs = em.createQuery(

2 "select d from Dog d where d.name like :name", Dog.class)

3 .setParameter("name", "Re%")

4 .getResultList();

This is it! Straight to the point, and you can even call it fluent! Probably the best we can do with Querydsl is adding one line to introduce shorter “alias” like this:

1 QDog d = new QDog("d1");

2 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(d)

4 .from(d)

5 .where(d.name.startsWith("Re"))

6 .fetch();

Using aliases is very handy especially for longer and/or more complicated queries. We could

use QDog.dog as the value, or here I introduced new query variable and named it d1. This

name will appear in generated JPQL that looks a little bit different from the JPQL in example

above:

1 select d1 from Dog d1 where d1.name like ?1 escape '!'

There is a subtle difference in how Querydsl generates like clause – which, by the way, is fully

customizable using Querydsl templates. But you can see that alias appears in JPQL, although neither

EclipseLink nor Hibernate bother to translate it to the generated SQL for your convenience.

Now, if we compare both code snippets above (alias creation included) we get a surprising result – there are more characters in the JPQL version! Although it’s just a nit-picking (line/char up or down), it’s clear that Querydsl can express JPQL extremely well (especially in 4.x version) and at the same time it allows for easy dynamic query creation.

You may ask about named queries. Here I admit right away, that Querydsl necessarily introduces overhead (see the next section on disadvantages), but when it comes to query reuse from programmer’s perspective Querydsl offers so called detached queries. While these are not covered in their reference manual (as of March 2016), we will talk more about them in a chapter about advanced Querydsl topics.

What about the cons?

Before we move to other Querydsl topics I’d go over its disadvantages. For one, you’re definitely adding some overhead. I don’t know exactly how big, maybe with the SQL backend (using JDBC directly) it would be more pronounced because ORM itself is big overhead anyway. In any case, there is an object graph of the query in the memory before it is serialized into JPQL – and from there it’s on the same baseline like using JPA directly.

This performance factor obviously is not a big deal for many Querydsl users (some of them are really big names), it mostly does not add too much to the SQL execution itself, but in any case – if you are interested you have to measure it yourself. Also realize that without Querydsl you either have to mess with JPQL strings before you have the complete dynamic WHERE part or you should compare it with Criteria API which does not have to go through JPQL, but also creates some object graph in the memory (richer or not? depends).

Documentation, while good, is definitely not complete. For instance, detached queries are not mentioned in their Querydsl Reference Guide and there is much more you need to find out yourself. You’ll need to find your own best practices, probably, but it is not that difficult with Querydsl. Based (not only) on my own experience, it is literally joy to work with Querydsl and explore what it can provide – for me it worked like this from day zero. It’s also very easy to find responses on the StackOverflow or their mailing-list, very often provided directly by Querydsl developers. This makes any lack of documentation easy to overcome.

Finally, you’re adding another dependency to the project, which may be a problem for some. For the teams I worked with it was well compensated by the code clarity Querydsl gave us.

Be explicit with aliases

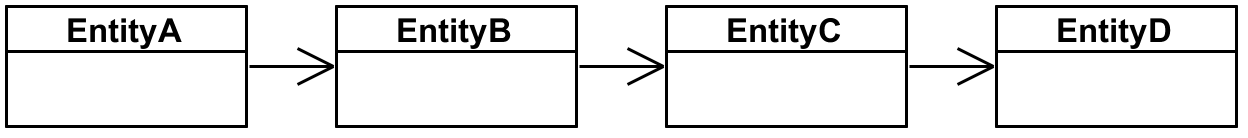

With attribute paths at our disposal it is easy to require some data without explicitly using joins. Let’s consider the following entity chain:

We will start all the following queries at EntityA and first we will want the list of related

EntityC objects. We may approach it like this:

1 List<EntityC> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityA.entityA.entityB.entityC)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .fetch();

This works and Hibernate generates the following SQL:

1 select

2 entityc2_.id as id1_5_,

3 entityc2_.entityD_id as entityD_3_5_,

4 entityc2_.name as name2_5_

5 from

6 EntityA entitya0_,

7 EntityB entityb1_ inner join

8 EntityC entityc2_ on entityb1_.entityC_id=entityc2_.id

9 where entitya0_.entityB_id=entityb1_.id

Effectively these are both inner joins and the result is as expected. But what happens if we

want to traverse to EntityD?

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityA.entityA.entityB.entityC.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .fetch();

After running this we end up with NullPointerException on the line with select method. What

happened? The core problem is that it is not feasible to generate infinitely deep path using

final fields. Querydsl offers some solutions to this as discussed in the reference

documentation.

You can either ask the generator to initialize the path you need with the @QueryInit annotation

or you can mark the entity with @Config(entityAccessors=true) which generates accessor methods

instead of final fields. In the latter case you’d simply use this annotation on EntityC and

in the select call use entityD() which would create the property on the fly. This way you can

traverse relations ad lib. It requires some Querydsl annotations on the entities – which you may

already use, for instance for custom constructors, etc.

However, instead of customizing the generation I’d advocate being explicit with the aliases. If there is a join let it show! We can go around the limitation of max-two-level paths using just a single join:

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityB.entityB.entityC.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 .join(QEntityA.entityA.entityB, QEntityB.entityB)

5 .fetch();

Here we lowered the nesting back to two levels by making EntityB explicit. We used existing

default alias QEntityB.entityB. This query makes the code run, but looks… unclean, really.

Let’s go all the way and make all the joins explicit:

1 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QEntityD.entityD)

3 .from(QEntityA.entityA)

4 // second parameter is alias for the path in the first parameter

5 .join(QEntityA.entityA.entityB, QEntityB.entityB)

6 // first parameter uses alias from the previous line

7 .join(QEntityB.entityB.entityC, QEntityC.entityC)

8 .join(QEntityC.entityC.entityD, QEntityD.entityD)

9 .fetch();

Now this looks long, but it says exactly what it does – no surprises. We may help it in a couple of ways but the easiest one is to introduce the aliases upfront:

1 QEntityA a = new QEntityA("a");

2 QEntityB b = new QEntityB("b");

3 QEntityC c = new QEntityC("c");

4 QEntityD d = new QEntityD("d");

5 List<EntityD> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

6 .select(d)

7 .from(a)

8 .join(a.entityB, b)

9 .join(b.entityC, c)

10 .join(c.entityD, d)

11 .fetch();

I like this most – it is couple of lines longer but very clean and the query is very easy to read. Anytime I work with joins I always go for explicit aliases.

Another related problem is joining the same entity more times (but in different roles). Newbie programmers also often fall for a trap of using the same alias – typically the default one offered on each Q-class – for multiple joins on the same entity. There can be two distinct local variables representing these aliases but they both point to the same object instance – hence it’s still the same alias. Whenever I join an entity more times in a query I always go for created aliases. When I’m sure that an entity is in a query just once I may use default alias. It really pays off to have a strict and clean strategy of how to use the aliases and local variables pointing at them.

Functions and operations

Let’s see what data we will work on in the next sections so we can understand the returned results.

| id | name |

|---|---|

| 1 | collie |

| 2 | german shepherd |

| 3 | retriever |

| name | age | breed_id |

|---|---|---|

| Lassie | 7 | 1 (collie) |

| Rex | 6 | 2 (german shepherd) |

| Ben | 4 | 2 (german shepherd) |

| Mixer | 3 |

NULL (unknown breed) |

The following examples can be found on GitHub in FunctionsAndOperations.java.

When we want to write some operation we simply follow the fluent API. You can write QDog.dog.age.

and hit auto-complete – this offers us all the possible operations and functions we can use on the

attribute. These are based on the known type of that attribute, so we only get the list of

functions that make sense (from technical point of view, not necessarily from business perspective,

of course).

This naturally makes sense for binary operations. If we want to see dog’s age halved we can do it like this:

1 List<Tuple> dogsGettingYounger = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.age.divide(2))

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .fetch();

We will cover Tuples soon, now just know they can be printed easily and the

output would be [[Lassie, 3], [Rex, 3], [Ben, 2], [Mixer (unknown breed), 1]]. We are not limited

to constants and can add together two columns or multiply amount by rate, etc. You may also

integer results of the division – this can be mended if you select age as double – like this:

1 // rest is the same

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.age.castToNum(Double.class).divide(2))

Unary functions are less natural as they are appended to the attribute expression just like binary operations – they just don’t take any arguments:

1 List<Tuple> dogsAndNameLengths = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QDog.dog.name.length())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .fetch();

This returns [[Lassie, 6], [Rex, 3], [Ben, 3], [Mixer (unknown breed), 21]]. JPA 2.1 allows

the usage of any function using the FUNCTION construct. We will cover this

later in the advanced chapter on Querydsl.

Aggregate functions

Using aggregate functions is the same like any other function – but as we know from SQL, we need to group by any other non-aggregated columns. For instance to see the counts of dogs for any age we can write:

1 List<Tuple> dogCountByAge = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.age, QDog.dog.count())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .groupBy(QDog.dog.age)

5 .fetch();

Our example data have each dog with different age, so the results are boring.

If we want to see the average age of dogs per breed we use this:

1 List<Tuple> dogAvgAgeByBreed = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.name, QDog.dog.age.avg())

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .groupBy(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.name)

6 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

7 .fetch();

Because of leftJoin this returns also line [null, null, 3.0]. With innerJoin (or just join)

we would get only dogs with defined breed. On screen I’m probably interested in breed’s name but

that relies on their uniqueness – which may not be the case. To get the “true” results per breed

I added breed.id into the select clause. We can always display just names and if they are not

unique user will at least be curious about it. But that’s beyond the discussion for now.

Querydsl supports having clause as well if the need arises. We also demonstrated orderBy

clause, just by the way, as it hardly deserves special treatment in this book.

Subqueries

Here we will use the same data like in the previous section on functions and operations. The following examples can be found on GitHub in Subqueries.java). You can also check Querydsl reference documentation.

Independent subquery

If we want to find all the dogs that are of breed with a long name, we can do this:

1 List<Dog> dogsWithLongBreedName = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.breed.in(

5 new JPAQuery<>() // no EM here

6 .select(QBreed.breed)

7 .from(QBreed.breed)

8 // no fetch on subquery

9 .where(QBreed.breed.name.length().goe(10))))

10 .fetch();

This returns Ben and Rex, both german shepherds. Note that subquery looks like normal query, but

we don’t provide EntityManager to it and we don’t use any fetch. If you do the subquery will

be executed on its own first and its results will be fetched into in clause just as any other

collection would. This is not what we want in most cases – especially when the code leads us to

an idea of a subquery. The previous result can be achieved with join as well – and in such cases

joins are almost always preferable.

To make our life easier we can use JPAExpressions.select(...) instead of

new JPAQuery<>().select(...). There is also a neat shortcut for the subquery with select and

from with the same expression.

1 JPAExpressions.selectFrom(QBreed.breed) ...

We will prefer using JPAExpression from now on. Another example finds average age of all dogs

and returns only those above it:

1 List<Dog> dogsOlderThanAverage = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .where(QDog.dog.age.gt(

5 JPAExpressions.select(QDog.dog.age.avg())

6 .from(QDog.dog)))

7 .fetch();

This is perhaps on the edge regarding usage of the same alias QDog.dog for both inner and outer

query, but I dare to say it does not matter here. In both previous examples the same result can be

obtained when we execute the inner query first because it always provides the same result. What if

we need to drive some conditions of the inner query by the outer one?

Correlated subquery

When we use object from the outer query in the subquery it is called correlated subquery. For example, we want to know for what breeds we have no dogs:

1 List<Breed> breedsWithoutDogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(

5 JPAExpressions.selectFrom(QDog.dog)

6 .where(QDog.dog.breed.eq(QBreed.breed))

7 .notExists())

8 .fetch();

We used a subquery with exist/notExists and we could omit select, although it can be used.

This returns a single breed – retriever. Interesting aspect is that the inner query uses

something from the outer select (here QBreed.breed). Compared to the subqueries from the

previous section this one can have different result for each row of the outer query.

This one can actually be done by join, as well, but in this case I’d not recommend it. Depending on

the mapping you use, various things work on various providers. When you have @ManyToOne Breed

breed than this works on EclipseLink:

1 List<Breed> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.eq(QDog.dog.breed))

5 .where(QDog.dog.isNull())

6 // distinct would be needed for isNotNull (breeds with many dogs)

7 // not really necessary for isNull as those lines are unique

8 .distinct()

9 .fetch();

Alas, it fails on Hibernate (5.2.2) with InvalidWithClauseException: with clause can only

reference columns in the driving table. It seems to be an open bug mentioned in this

StackOverflow answer – and the suggested solution

of using plain keys instead of objects indeed work:

1 // the rest is the same

2 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.id.eq(QDog.dog.breedId))

For this we need to switch Breed breed mapping to plain FK mapping, or use both of them with

one marked with updatable false:

1 @Column(name = "breed_id", updatable = false, insertable = false)

2 private Integer breedId;

You may be tempted to avoid this mapping and do explicit equals on keys like this:

1 // the rest is the same

2 .leftJoin(QDog.dog).on(QBreed.breed.id.eq(QDog.dog.breed.id))

But this has its own issues. EclipseLink joins the breed twice, second time using implicit join after left join which is a construct that many databases don’t really like (H2 or SQL Server, to name just those where I noticed this quite often) and it fails on JDBC/SQL level. Hibernate also generates the superfluous join to the breed but at least orders them more safely. Still, if you use EclipseLink simply don’t add explicit IDs to your paths and if you’re using Hibernate at least know it’s not efficient join-wise and also is not really portable across JPA providers.

There is another JPA query that works and also arguably reads most naturally:

1 List<Breed> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.dogs.isEmpty())

5 .fetch();

Internally this generates subquery with count or (not) exists anyway, there is no way around it.

But for this to work we also have to add the mapping to Breed which was not necessary for the

previous non-JPA joins:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed")

2 private Set<Dog> dogs;

This mapping may be rather superfluous for some cases (why should breed know the list of dogs?) but it should not hurt.

We somehow foreshadowed themes from the following chapters on various mapping problems but we’re not done with subqueries (or Querydsl) just yet. Let’s now try to find dogs that are older than average – but this time for each breed:

1 QDog innerDog = new QDog("innerDog");

2 List<Dog> dogsOlderThanBreedAverage = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(QDog.dog)

4 .from(QDog.dog)

5 .where(QDog.dog.age.gt(

6 JPAExpressions.select(innerDog.age.avg())

7 .from(innerDog)

8 .where(innerDog.breed.eq(QDog.dog.breed))))

9 .fetch();

Notice the use of innerDog alias which is very important. Had you used QDog.dog in the subquery

it would have returned the same results like dogsOlderThanAverage above. This query returns only

Rex, because only german shepherds have more than a single dog – and a single (or no) dog can’t be

older than average.

This section is not about going deep into subquery theory (I’m not the right person for it in the

first place), but to demonstrate how easy and readable it is to write subqueries with Querydsl

API. We’re still limited by JPQL, that means no subqueries in from or select clauses). When

writing subqueries be careful not to “reuse” alias from the outer query.

Pagination

Very often we need to cut our results into smaller chunks, typically pages for some user interface,

but pagination is often used also with various APIs. To do it manually, we can simply specify

offset (what record is the first) and limit (how many records):

1 List<Breed> breedsPageX = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17)) // random where

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

6 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

7 .limit(pageSize)

8 .fetch();

I used variables page (starting at one, hence the correction) and pageSize to calculate the

right values. Any time you paginate the results you want to use orderBy because SQL specification

does not guarantee any order without it. Sure, databases typically give you results in some natural

order (like “by ID”), but it is dangerous to rely on it.

Content of the page is good, but often we want to know total count of all the results. We use the

same query with the same conditions, we just first use .fetchCount like this:

1 JPAQuery<Breed> breedQuery = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17))

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc());

6

7 long total = breedQuery.fetchCount();

8 List<Breed> breedsPageX = breedQuery

9 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

10 .limit(pageSize)

11 .fetch();

We can even add if skipping the second query when count is 0 as we can just create an empty list.

And because this scenario is so typical Querydsl provides a shortcut for it:

fetchResults 1 QueryResults<Breed> results = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.id.lt(17))

5 .orderBy(QBreed.breed.name.asc())

6 .offset((page - 1) * pageSize)

7 .limit(pageSize)

8 .fetchResults();

9 System.out.println("total count: " + results.getTotal());

10 System.out.println("results = " + results.getResults());

QueryResults wrap all the information we need for paginated result, including offset and limit.

It does not help us with reverse calculation of the page number from an offset, but I guess we

probably track the page number in some filter object anyway as we needed it as the input in the

first place.

And yes, it does not execute the second query when the count is zero.4

Tuple results

When you call fetch() the List is returned. When you call fetchOne() or fetchFirst() one

object is returned. The question is – what type of object? This depends on the select clause

which can have a single parameter which determines the type or you can use list of expressions

for select in which case Tuple is returned. That is, a query with select(QDog.dog) will

return Dog (or List<Dog>) because QDog.dog is of type QDog that extends

EntityPathBase<Dog> which eventually implements Expression<Dog> – hence the Dog.

But when you return multiple results we need to wrap them somehow. In JPA you will get Object[]

(array of objects) for each row. That works, but is not very convenient. Criteria API brings

Tuple for that reason which is much better. Querydsl uses Tuple idea as well. What’s the deal?

1 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog.name, QBreed.breed.name)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .join(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .fetch();

6 result.forEach(t -> {

7 String name = t.get(QDog.dog.name);

8 String breed = t.get(1, String.class);

9 System.out.println("Dog: " + name + " is " + breed);

10 });

As you can see in the forEach block we can extract columns by either using the expression that

was used in the select as well (here QDog.dog.name) or by index. Needless to say that the first

way is preferred. You can also extract the underlying array of objects using toArray().

Because Tuple works with any expression we can use the whole entities too:

1 List<Tuple> result = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog, QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .join(QDog.dog.breed, QBreed.breed)

5 .fetch();

6 result.forEach(t -> {

7 Dog dog = t.get(QDog.dog);

8 Breed breed = t.get(QBreed.breed);

9 System.out.println("\nDog: " + dog);

10 System.out.println("Breed: " + breed);

11 });

And of course, you can combine entities with columns ad-lib.

There are other ways how to combine multiple expressions into one object. See the reference guide to see how to populate beans, or how to use projection constructors.

Fetching to-many eagerly

In the following example we select all the breeds and we want to print the collection of the dogs of that breed:

1 // mapping on Breed

2 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed")

3 private Set<Dog> dogs;

4

5 // query

6 List<Breed> breed = new JPAQuery<>(em)

7 .select(QBreed.breed)

8 .from(QBreed.breed)

9 .fetch();

10 breed.forEach(b ->

11 System.out.println(b.toString() + ": " + b.getDogs()));

This executes three queries. First the one that is obvious and then one for each breed when you

want to print the dogs. Actually, for EclipseLink it does not produce the other queries and merely

prints {IndirectSet: not instantiated} instead of the collection content. You can nudge

EclipseLink with something like b.getDogs().size() or other meaningful collection operation.

It seems toString() isn’t meaningful enough for EclipseLink.

We can force the eager fetch when we adjust the mapping:

1 @OneToMany(mappedBy = "breed", fetch = FetchType.EAGER)

2 private Set<Dog> dogs;

However, while the fetch is eager, EclipseLink still does it with three queries (1+N in general).

Hibernate uses one query with join. So yes, it is eager, but not necessarily efficient. There is

a potential problem with paging when using join to to-many – the problem we mentioned

already and we’ll return to it later. What happens when

we add offset and limit?

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .offset(1)

5 .limit(1)

6 .fetch();

Because EclipseLink uses separate query for breeds, nothing changes and we get the second result (by the way, we forgot to order it!). Hibernate is smart enough to use separate query too, as soon as it smells the offset/limit combo. It makes sense, because query says “gimme breeds!” – although not everything in JPA is always free of surprises. In any case, eager collection is not recommended. There may be notable exceptions – maybe some embeddables or other really primitive collections – but I’d never risk fetching collection of another entities as it asks for fetching the whole database eventually.

What if we write a query that joins breed and dogs ourselves? We assuming no pagination again.

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .join(QBreed.breed.dogs, QDog.dog)

5 .distinct()

6 .fetch();

7 breeds.forEach(b ->

8 System.out.println(b.toString() + ": " + b.getDogs()));

If you check the logs queries are indeed generated with joins, but it is not enough. EclipseLink

still prints uninitialized indirect list (and relevant operation would trigger the select),

Hibernate prints it nicely, but needs additional N selects as well. We need to say what collection

we want initialized explicitly using fetchJoin like so:

1 List<Breed> breeds = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .join(QBreed.breed.dogs).fetchJoin()

5 .distinct()

6 .fetch();

You use fetchJoin() just after the join with a collection path and in this case you don’t

need to use second parameter with alias, unless you want to use it in where or select, etc.5

Because we used join with to-many relations ourselves JPA assumes we want all the results

(5 with our demo data defined previously). That’s why we also added

distinct() – this ensures we get only unique results from the select clause. But these unique

results will still have their collections initialized because SQL still returns 5 results and

JPA “distincts” it in post-process. This means we cannot paginate queries with joins, distinct

or not. This is something we will tackle in a dedicated section.

Querydsl and code style

Querydsl is a nice API and DSL but may lead to horrific monsters like:

1 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction

3 .clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.transactionId))

4 .from(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement)

5 .join(QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount).on(

6 QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementId

7 .eq(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement.id))

8 .join(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction)

9 .on(QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.

10 clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountId

11 .eq(QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount.id))

12 .where(QClientAgreement.clientAgreement.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

13 .fetch();

The problems here are caused by long entity class names but often there is nothing you can do about

it. Querydsl exacerbates it with the duplication of the name in QClassName.className. There are

many ways how to tackle the problem.

We can introduce local variables, even with very short names as they are very close to the

query itself. In most queries I saw usage of acronym aliases, like cabat for

QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction. This clears up the query significantly, especially when

the same alias is repeated many times:

1 QClientAgreement ca = QClientAgreement.clientAgreement;

2 QClientAgreementBankAccount caba =

3 QClientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementBankAccount;

4 QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction cabat =

5 QClientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction;

6 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

7 .select(cabat.transactionId)

8 .from(ca)

9 .join(caba).on(caba.clientAgreementId.eq(ca.id))

10 .join(cabat).on(cabat.clientAgreementBankAccountId.eq(caba.id))

11 .where(ca.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

12 .fetch();

You give up some explicitness in the query with those acronyms but you get much higher signal-to-noise ratio which can easily overweight the burden of mental mapping to local variables.

Another option is to use static imports which halves the QNames into half:

1 Integer trnId = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.transactionId)

3 .from(clientAgreement)

4 .join(clientAgreementBankAccount).on(

5 clientAgreementBankAccount.clientAgreementId.eq(clientAgreement.id))

6 .join(clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction).on(

7 clientAgreementBankAccountTransaction.clientAgreementBankAccountId

8 .eq(clientAgreementBankAccount.id))

9 .where(clientAgreement.id.in(clientAgreementsToDelete))

10 .fetch()

This is clearly somewhere between the first (totally unacceptable) version and the second where

the query was very brief at the cost of using acronyms for aliases. Using static names is great

when they don’t collide with anything else. But while QDog itself says clearly it is metadata

type, name of its static field dog clearly collides with any dog variable of a real Dog type

you may have in your code. Still, we use static imports extensively in various infrastructural

code where no confusion is possible.

We also often use field or variable named $ that represents the root of our query. I never ever

use that name for anything else and long-term experiments showed that it brought no confusion into

our team whatsoever. Snippet of our DAO class may look like this:

1 public class ClientDao {

2 public static final QClient $ = QClient.client;

3

4 public Client findByName(String name) {

5 return queryFrom($) // our shortcut for new/select/from

6 .where($.name.eq(name))

7 .fetchOne($);

8 }

9

10 public List<Client> listByRole(ClientRole clientRole) {

11 return queryFrom($)

12 .where($.roles.any().eq(clientRole))

13 .list($);

14 }

15 ...

As a bonus you can see how any() is used on collection path $.roles. You can even go on

to a specific property – for instance with our demo data we can obtain list of breeds where any

dog is named Rex like this:

1 List<Breed> breedsWithRex = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .where(QBreed.breed.dogs.any().name.eq("Rex"))

5 .fetch();

This produces SQL with EXISTS subquery although the same can be written with join

and distinct.

More

That’s it for our first tour around Querydsl. We will see more in the chapter on more advanced features (or perhaps just features used less). In the course of this chapter there was plenty of links to other resources too – let’s sum it up:

- Querydsl Reference Guide is the first stop when you want to learn more. It is not the last stop though, as it does not even cover all the stuff from this chapter. It still is a useful piece of documentation.

- Querydsl is also popular enough on StackOverflow with Timo Westkämper himself often answering the questions.

- Finally there is their mailing-list

(

querydsl@googlegroups.com) – with daily activity where you get what you need.

For an introduction you can also check this slide deck that covers older version 3, but except for the fluent API changes the concept is the same.