10. Modularity, if you must

I’m convinced that people who designed and specified JPA were not aware (or were ignorant) of modern modularity trends.10 For a long time I’ve been trying to put things into domain named packages (sometimes low-level technical domains, as it happens with complex layered software) and as a next step I naturally started to split big JARs into smaller ones rather across vertical (domain) lines instead of putting everything from one layer in a single JAR.

If you have all your entities in a single JAR you have no problem altogether. But if you fancy to

split the entities into multiple JARs – including their definitions in

persistence.xml – then you’re venturing beyond the JPA specification. JPspec,

section 8.2 Persistence Unit Packaging says:

This does not explicitly forbid using multiple persistence.xml files but I believe it implies we

should not do it. It’s actually the other way around – we can have multiple persistence units

in one XML, that’s a piece of cake.

Everybody knows layers

I decided to experiment with modularization of applications after I had read Java Application Architecture: Modularity Patterns with Examples Using OSGi [JAA].11 After that I couldn’t sleep that well with typical mega-JARs containing all the classes at a particular architectural level. Yeah, we modularize but only by levels.

I’ll use one of the projects from my past as an example. We had one JAR with all entity classes,

sometimes it was called domain, sometimes jpa-entities (admitting the anemic domain

model).

Then we had our @Service classes in a different JAR – but all of them in one – accessing

entities via DAOs. Service layer was used by a presentation layer. Complex logic was pushed to

specific @Components somewhere under the service layer. It was not domain-driven but it made

sense for us and the dependencies flowed clearly from the top down.

Components based on features

But how about dependencies between parts of the system at the same level? When we have a lot of

entity classes, some are pure business (Clients, their Transactions, financial Instruments), some

are rather infrastructural (meta model, localization, audit trail). Why can’t these be separated?

Most of the stuff depends on meta model, localization is quite independent in our case, audit trail

needs meta model and permission module. It all clicks when one thinks about

it – and it is more or less in line with modularity based on features, not on technology or

layers. Sure we can still use layer separation and have permission-persistence and

permission-service as well (later we will see an example where it makes a lot of sense).

Actually, this is quite a repeating question: Should we base packages by features or by layer/technology/pattern? It seems that the consensus was reached – start by feature – which can be part of your business domain. If stuff gets big you can split them into layers too, unless you find even more suitable sub-domains.

Multiple JARs with JPA entities

So we carefully try to put different entity classes into different JAR modules. Sure, we can just repackage them in the same JAR and check how tangled they are with Sonar but it is recommended to enforce the separation and to make dependencies explicit (not only in the [JAA] book). My experience confirms it quite clearly – contracts of any kind must be enforced.

And here comes the problem when your persistence is based on JPA. Because JPA clearly wasn’t

designed to have a single persistence unit across multiple persistence.xml files. So what are

these problems actually?

- How to distribute

persistence.xmlacross these JARs? Do we even have to? - What classes need to be mentioned where? E.g., we need to mention classes from an upstream JARs

in

persistence.xmlif they are used in relations (which breaks the DRY principle). - When we have multiple

persistence.xmlfiles, how to merge them in our persistence unit configuration? - What about the configuration in

persistence.xml? What properties are used from what file? (Little spoiler, we just don’t know reliably!) Where to put them so we don’t have to repeat ourselves again? - How to use EclipseLink static weaving for all these modules? How about a module with only

abstract mapped superclass (some

dao-commonmodule)?

That’s quite a lot of problems for an age when modularity is so often mentioned, too many for a technology that comes from an “enterprise” stack. And they are mostly phrased as questions – because the answers are not readily available.

Distributing persistence.xml – do we need it?

This one is difficult and may depend on the provider you use and the way you use it. We use

EclipseLink and its static weaving. This requires persistence.xml. Sure we may try keep it

together in some neutral module (or any path, as it can be configured for weaving plugin), but

that goes against the modularity quest. What options do we have?

- We can create some union

persistence.xmlin a module that depends on all needed JARs. This would be OK if we had just one such module – typically some downstream module like WAR or runnable JAR. But we have many. If we madepersistence.xmlfor each they would contain a lot of repetition. And we’d reference downstream resource which is unacceptable. - We can have dummy upstream module or out of module path with union

persistence.xml. This would keep things simple, but it would be more difficult to develop modules independently, maybe even with different teams. - Keep

persistence.xmlin the JAR with related classes. This seems best from the modularity point of view, but it means we need to merge multiplepersistence.xmlfiles when the persistence unit starts. - Or can we have different persistence unit for each

persistence.xml? This is OK, if they truly are in different databases (different JDBC URL), otherwise it doesn’t make sense. In our case we have rich DB and any module can see the part it is interested in – that is entities from the JARs it has on the classpath. If you have data in different databases already, you’re probably sporting microservices anyway.

We went for the third option – especially because EclipseLink’s weaving plugin likes it and we

didn’t want to redirect to non-standard path to persistence.xml – but it also seems to be the

right logical way. However, there is nothing like dependency between persistence.xml files. So if

we have b.jar that uses a.jar, and there is entity class B in b.jar that contains

@ManyToOne to A entity from a.jar, we have to mention A class in persistence.xml in

b.jar. Yes, the class is already mentioned in a.jar, of course. Again, clearly, engineers of

JPA didn’t even think about possibility of using multiple JARs in a really modular way.

In any case – this works, compiles, weaves our classes during build – and more or less answers questions 1 and 2 from our problem list.

It doesn’t start anyway

When we have a single persistence.xml it will get found as a unique resource, typically in

META-INF/persistence.xml – in any JAR actually (the one JPA refers to as “the root of

persistence unit”). But when we have more of them they don’t get all picked and merged magically

– and the application fails during startup. We need to merge all those persistence.xml files

during the initialization of our persistence unit. Now we’re tackling questions 3 and 4 at once,

for they are linked.

To merge all the configuration XMLs into one unit we can use this configuration for

PersistenceUnitManger in Spring (using MergingPersistenceUnitManager is the key):

1 @Bean

2 public PersistenceUnitManager persistenceUnitManager(DataSource dataSource) {

3 MergingPersistenceUnitManager persistenceUnitManager =

4 new MergingPersistenceUnitManager();

5 persistenceUnitManager.setDefaultDataSource(dataSource);

6 persistenceUnitManager.setDefaultPersistenceUnitName("you-choose");

7 // default persistence.xml location is OK, goes through all classpath*

8 return persistenceUnitManager;

9 }

Before I unveil the whole configuration we should talk about the configuration that was in

the original singleton persistence.xml – which looked something like this:

1 <exclude-unlisted-classes>true</exclude-unlisted-classes>

2 <shared-cache-mode>ENABLE_SELECTIVE</shared-cache-mode>

3 <properties>

4 <property name="eclipselink.weaving" value="static"/>

5 <property name="eclipselink.allow-zero-id" value="true"/>

6 <!--

7 Without this there were other corner cases when field change was ignored.

8 This can be worked-around calling setter, but that sucks.

9 -->

10 <property name="eclipselink.weaving.changetracking" value="false"/>

11 </properties>

The biggest question here is: What is used during build (e.g. by static weaving) and what can be put into runtime configuration somewhere else? Why somewhere else? Because we don’t want to repeat these properties in all XMLs.

Now we will take a little detour to shared-cache-mode that displays the problem with merging

persistence.xml files in the most bizarre way.

Shared cache mode

We wanted to enable cached entities selectively (to ensure that @Cacheable annotations have any

effect). But I made a big mistake when I created another persistence.xml file – I forgot to

mention shared-cache-mode there. My persistence unit picked both XMLs (using

MergingPersistenceUnitManager) but my caching went completely nuts. It cached more than expected

and I was totally confused. The trouble here is – persistence.xml don’t get really merged.

The lists of classes in them do, but the configurations do not. Somehow my second persistence XML

became dominant (one always does!) and because there was no shared-cache-mode specified, it

used defaults – which is anything EclipseLink thinks is the best. No blame there, just another

manifestation that JPA people didn’t even think about this setup scenarios.

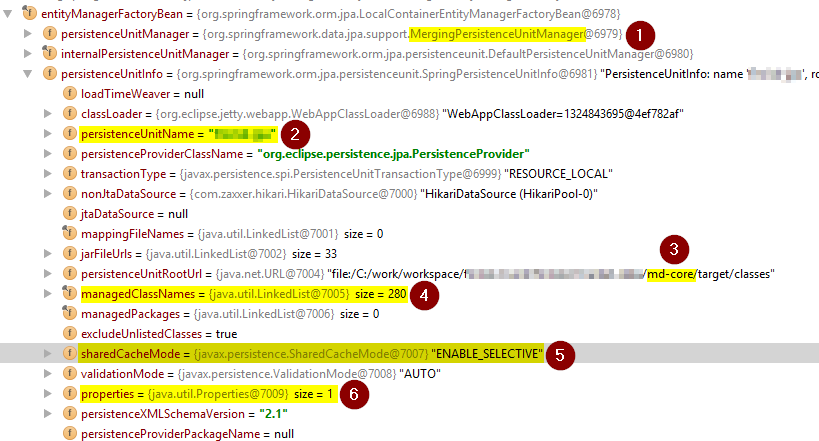

If you really want to get some hard evidence how things are in your setup put a breakpoint

anywhere you can reach your configured EntityManagerFactory and when it stops there dig deeper

to find what your cache mode is. Or anything else – you can check the list of known entity

classes, JPA properties, anything really. And it’s much faster than guessing.

In the picture above we can see the following:

- We’re using Springs

MergingPersistenceUnitManager. - Persistence unit name is as expected.

- This is the path of “the root of the persistence unit”. It’s a directory here, but it would be a JAR in production.

- Our managed classes (collapsed here).

- Shared cache mode is set to

ENABLE_SELECTIVE– as required. - Other cofigured properties.

Luckily, we don’t rely on the persistence.xml root anymore, at least not for runtime

configuration.

Putting the Spring configuration together

Now we’re ready to wrap up our configuration and move some of repeated configuration snippets from

persistence.xml into Spring configuration – here we will use Java-based configuration (XML works

too, of course).

Most of our properties were related to EclipseLink. I had read their weaving manual, but I still didn’t understand what works when and how. I had to debug some of the stuff to be really sure.

It seems that eclipselink.weaving is the crucial property namespace, that should stay in our

persistence.xml, because it gets used by the plugin performing the static weaving. I debugged

Maven build and the plugin definitely uses property eclipselink.weaving.changetracking

(we set it to false which is not default). Funny enough, it doesn’t need eclipselink.weaving

itself because running the plugin implies we wish for static weaving. During startup it gets

picked though, so EclipseLink knows it can treat classes as statically weaved. This means it

can be pushed into programmatic configuration.

The rest of the properties (and shared cache mode) are clearly used at the startup time. Spring configuration may then look like this:

1 @Bean public DataSource dataSource(...) { /* as usual */ }

2

3 @Bean

4 public JpaVendorAdapter jpaVendorAdapter() {

5 EclipseLinkJpaVendorAdapter jpaVendorAdapter = new EclipseLinkJpaVendorAdapter();

6 jpaVendorAdapter.setShowSql(true);

7 jpaVendorAdapter.setDatabase(

8 Database.valueOf(env.getProperty("jpa.dbPlatform", "SQL_SERVER")));

9 return jpaVendorAdapter;

10 }

11

12 @Bean

13 public PersistenceUnitManager persistenceUnitManager(DataSource dataSource) {

14 MergingPersistenceUnitManager persistenceUnitManager =

15 new MergingPersistenceUnitManager();

16 persistenceUnitManager.setDefaultDataSource(dataSource);

17 persistenceUnitManager.setDefaultPersistenceUnitName("you-choose");

18 persistenceUnitManager.setSharedCacheMode(

19 SharedCacheMode.ENABLE_SELECTIVE);

20 // default persistence.xml location is OK, goes through all classpath*

21

22 return persistenceUnitManager;

23 }

24

25 @Bean

26 public FactoryBean<EntityManagerFactory> entityManagerFactory(

27 PersistenceUnitManager persistenceUnitManager, JpaVendorAdapter jpaVendorAdapter)

28 {

29 LocalContainerEntityManagerFactoryBean emfFactoryBean =

30 new LocalContainerEntityManagerFactoryBean();

31 emfFactoryBean.setJpaVendorAdapter(jpaVendorAdapter);

32 emfFactoryBean.setPersistenceUnitManager(persistenceUnitManager);

33

34 Properties jpaProperties = new Properties();

35 jpaProperties.setProperty("eclipselink.weaving", "static");

36 jpaProperties.setProperty("eclipselink.allow-zero-id",

37 env.getProperty("eclipselink.allow-zero-id", "true"));

38 jpaProperties.setProperty("eclipselink.logging.parameters",

39 env.getProperty("eclipselink.logging.parameters", "true"));

40 emfFactoryBean.setJpaProperties(jpaProperties);

41 return emfFactoryBean;

42 }

Clearly, we can set the database platform, shared cache mode and all runtime relevant properties

programmatically – and we can do it at a single place. This is not a problem for a single

persistence.xml, but in any case it offers better control. We can now use Spring’s

@Autowired private Environment env; and override whatever we want with property files or even

-D JVM arguments – and still fallback to default values – just as we do for database property

of the JpaVendorAdapter. Or we can use SpEL.

This is the flexibility that persistence.xml simply cannot provide.

And of course, all the things mentioned in the configuration can now be removed from all our

persistence.xml files.

I’d love to get rid of eclipselink.weaving.changetracking in the XML too, but I don’t see any way

how to provide this as the Maven plugin configuration option, which we have neatly unified in our

parent POM. That would also eliminate some repeating.

Common base entity classes in separate JAR

The question 5 from our problem list is no problem after all the previous, just a nuisance.

EclipseLink refuses to weave our base class regardless of @MappedSuperclass usage. But as

mentioned in one SO question/answer, just add dummy

concrete @Entity class and we are done. You’ll never use it, it is no problem at all. And you can

vote for this bug.

This may be no issue for load-time weaving or for Hibernate, but I haven’t tried that so I can’t claim it reliably.

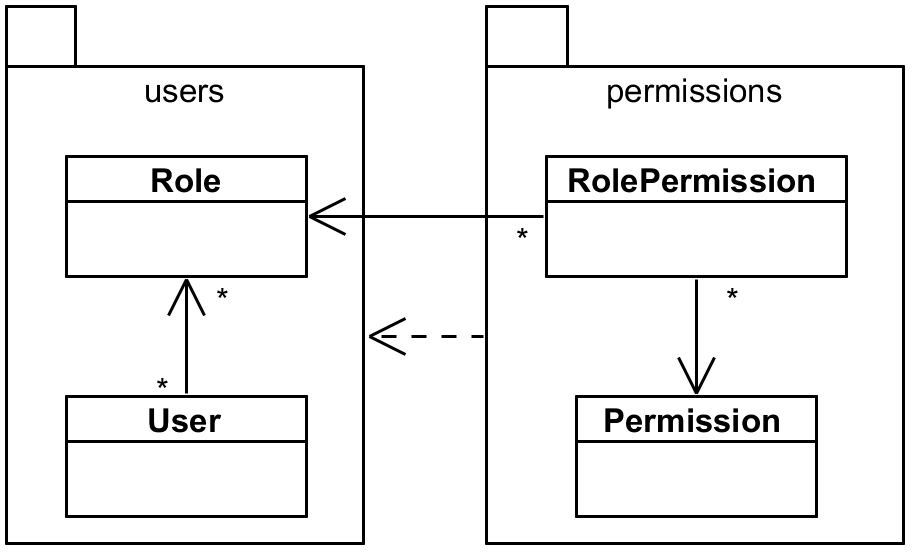

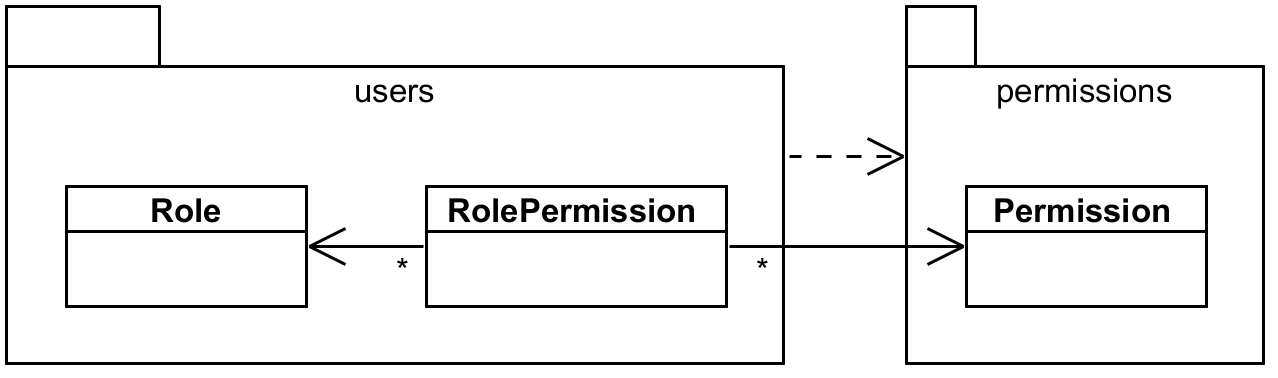

Cutting cyclic dependencies

Imagine we have two modules – users and permissions – where permissions depends on the

users module. Module users contains User and Role entity while permission module contains

Permission and RolePermission association that is mapped explicitly because it contains some

additional information. See the following picture:

users and permissionsObviously, Role cannot depend on RolePermission because that would cross module boundaries

in a wrong direction. But when the Role is deleted we also want to remove all related

RolePermission (but not Permission, of course). Imagine we have RoleDao and

RolePermissionDao and both these are derived from some layer supertype

named BaseDao. This handy class implements all common functionality, including delete(...)

method that in the process calls common preDelete(entity) method. For convenience this is

already pre-implemented, but does nothing.

Were all the classes in a single module our RoleDao could contain this:

1 @Override

2 protected void preDelete(Role entity) {

3 QRolePermission rp = QRolePermission.rolePermission;

4 new JPADeleteClause(entityManager, rp)

5 .where(rp.roleId.eq(entity.getId()))

6 .execute();

7 }

With separate modules it’s not possible because QRolePermission (just like RolePermission)

is not available in the users module.

Sure, we can argue whether we have the entities split into modules properly – for instance, is

Role really a concept belonging to User without considering permissions? However after moving

Role to the permissions module, we would have problem with @ManyToMany relationship named

roles on the User class – which is naturally the owning side of the relationship – as it

would go against module dependency.

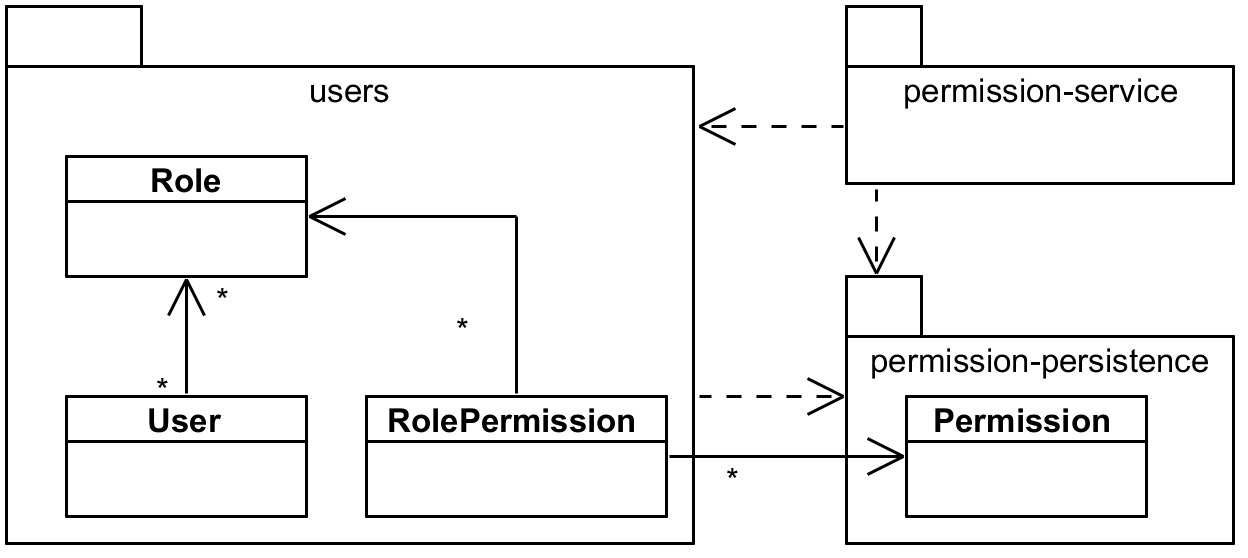

When the cycle occurs it may also indicate that one of the modules is too big. In our case we

used User in the permission module, but it is not really necessary in the entities directly.

It is used by upper layers of the module so maybe we should split the modules like this:

users and permissions dependency with introducing another module.Now users module can depend on permission-persistence and bring RolePermission where it

really belongs.

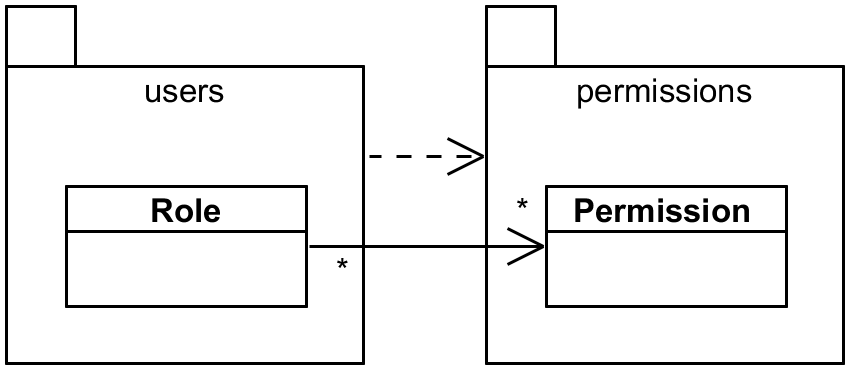

In the following cases we will focus on the relationship between the entities Role and

Permission – this time with modules users always depending on the permissions module (which

more or less matches permissions-persistence from the previous picture). Let’s see how we can

model that many-to-many relationship and how it can cross module boundaries.

@ManyToMany follows the dependency.First we use implicit role_permission table without explicit entity. Role is a natural owner

of the information about its Permissions and Permission doesn’t necessarily need the list of

the roles using it. It gets interesting when we introduce RolePermission explicitly as an entity

– perhaps because there are additional attributes on that association.

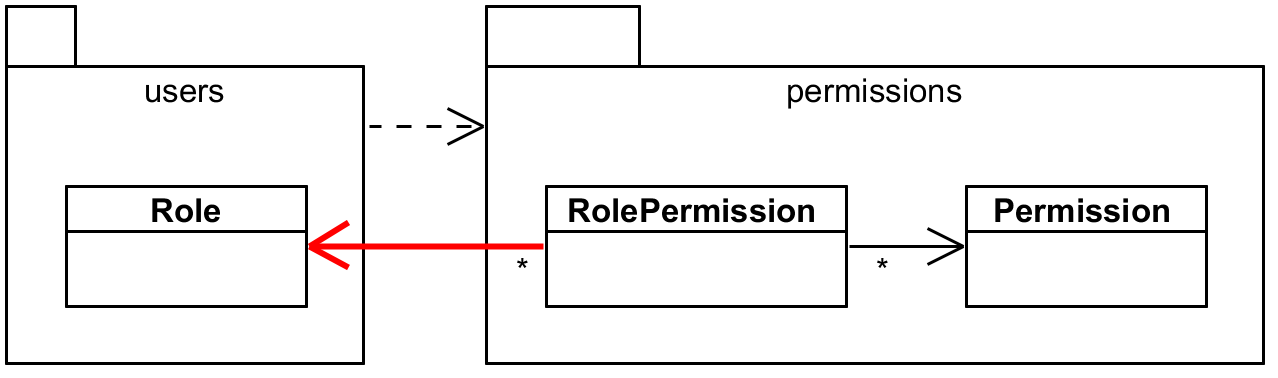

RolePermission in users.Notice that the database relational design limitations, dictating where to put the foreign key,

are actually quite useful to decide which way the dependency goes. The module knowing about

RolePermission table is the one that depends on the other one. If it wasn’t that way

we would get invalid case with cyclic dependency like this:

RolePermission in permissions forms a cycle.We either need to reverse the dependency on the module or split one module into two like shown

previously with permissions. If we absolutely needed this dependency from users to

permissions and also the “red arrow” then something else in the users model depends on

permission – which is a case for splitting users module. (This is rather unnatural, previous

case for splitting permissions was much better.)

In any of these cases we still have a problem when we delete the “blind” side of the relationship.

In the pictures of valid cases it was the Permission entity. Deletion of a Permission somehow

needs to signal to the users module that it needs to remove relations too. For that we can use

the Observer pattern that allows us to register

an arbitrary callback with a DAO.

It will be implemented by already mentioned BaseDao to make it generally available. The following

example demonstrates how it can be used when explicit RolePermission entity is used:

1 // in some dao-base module

2 public abstract class BaseDao<T> ... {

3 private List<PreDeleteHook<T>> preDeleteHooks = new ArrayList<>();

4

5 public void delete(T entity) {

6 preDeleteHooks.forEach(h -> h.preDelete(entity));

7 entityManager.remove(entity);

8 ...

9 }

10

11 public interface PreDeleteHook<E> {

12 void preDelete(E entity);

13 }

14

15 public void addPreDeleteHook(PreDeleteHook<T> hook) {

16 preDeleteHooks.add(hook);

17 }

18 ...

19 }

20

21 // in users module

22 public class RolePermissionDao extends BaseDao<RolePermission> {

23 public static final QRolePermission $ = QRolePermission.rolePermission;

24

25 @Autowired PermissionDao permissionDao; // from downstream permissions module, OK

26

27 @PostConstruct public void init() {

28 permissionDao.addPreDeleteHook(this::deleteByPermission);

29 }

30

31 // this method "implements" PreDeleteHook<Permission>

32 public void deleteByPermission(Permission permission) {

33 new JPADeleteClause(entityManager, $)

34 .where($.permissionId.eq(permission.getId()))

35 .execute();

36 }

37 ...

38 }

39

40 // no special changes in PermissionsDao, it can't know about users module anyway

Using unmanaged association table with @ManyToMany would require to find all the Roles having

this permission and removing it from its permissions collection. I, again, vouch for more

explicit way as that “delete all relations that use this permissions” is simpler and likely more

efficient.

Conclusion

- JPA clearly wasn’t designed with modularity in mind – especially not when modules form a single persistence unit, which is perfectly legitimate usage. Just because we use one big legacy database it doesn’t mean we don’t want to factor our code into smaller modules.

- It is possible to distribute persistence classes into multiple JARs, and then:

- We can go either with a single union

persistence.xml, which can be downstream or upstream – this depends if we need it only in runtime or during build too. - I believe it is more proper to pack partial

persistence.xmlinto each JAR, especially if we need it during build. Unfortunately, there is no escape from repeating some upstream classes in the module again just because they are referenced in relations (typical culprit when some error makes you scream “I don’t understand how this is not an entity, when it clearly is!”).

- We can go either with a single union

- If we have multiple

persistence.xmlfiles, it is possible to merge them using Spring’sMergingPersistenceUnitManager. I don’t know if we can use it for non-Spring applications, but I saw this idea reimplemented and it wasn’t that hard. (If I had to reimplement it, I’d try to merge the configuration part too!) - When we are merging

persistence.xmlfiles it is recommended to minimize configuration in them so it doesn’t have to be repeated. E.g., for Eclipselink we leave only stuff necessary for built-time static weaving, the rest is set programmatically in our Spring@Configurationclass.

There are still some open questions but I think they lead nowhere. Can I use multiple persistence

units with a single data source? This way I can have each persistence.xml as a separate unit.

But I doubt relationships would work across these and the same goes for transactions (without XA

that is).