9. Removing to-one altogether

To get full control over the fetching – and to do it without any high-tech solution – we have to

drop the relationship mapping and map row foreign key instead. Before we go on, we will discuss the

important addition of the ON keyword in JPA 2.1.

Why do we need ON anyway?

ON was dearly missing for other practical reasons. While this does not relate to to-one

mapping, let’s see an example:

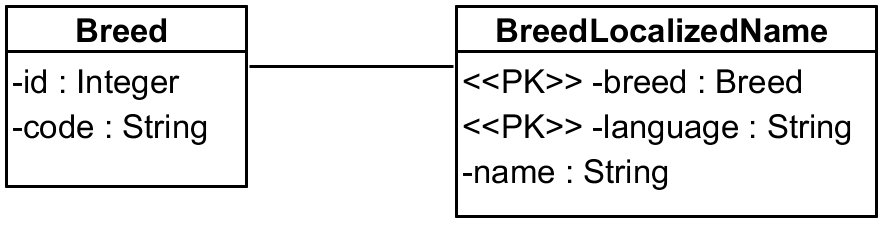

Here the Breed does not have a name, only some synthetic code, and names are offered in multiple

languages thanks to BreedLocalizedName. Demo code is

here.

Our favourite breeds are:

- wolf, with code

WLFand localized names for English and Slovak (wolf and vlk respectively – and yes, I know a wolf is not a dog), - collie, with code

COLwith localized name available only for Slovak (kólia).

Now imagine we want to get list of all breeds with English names. If the localized name is not available for our requested language, we still want to see the breed with its code in the list in any case. This may seem ridiculous to SQL guys, but it’s a real problem for some Java programmers. The first naive attempt may be:

JOIN to localized names1 QBreedLocalizedName qbn = QBreedLocalizedName.breedLocalizedName;

2 List<Tuple> breedEnNames = new JPAQuery<>(em)

3 .select(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.code, qbn.name)

4 .from(QBreed.breed)

5 .join(QBreed.breed.names, qbn)

6 .where(qbn.language.eq("en"))

7 .fetch();

But this produces unsatisfiable results containing only [1, WLF, wolf]. “When I join the

localized names to the breed list some results are gone!” our programmer complains. Ok, let’s

introduce the LEFT JOIN concept to them. Next attempt:

LEFT JOIN without ON clause1 breedEnNames = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.code, qbn.name)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .leftJoin(QBreed.breed.names, qbn)

5 .where(qbn.language.eq("en"))

6 .fetch();

It seems promising at first, but the result is again only a single lone wolf. There is one

difference though, although the WHERE clause wipes it out. If there was any breed without any

localized name at all it would be preserved after the JOIN. WHERE eliminates it only because

the value for language column would be NULL and not “en”. We could try to overcome it by an

additional .or(qbn.language.isNull()) in the WHERE part, but this would work only for rows

with no localized name – but not for those who have missing “en” localizations.

The trick is that the condition must be part of the LEFT JOIN – and that’s what ON is all

about. Let’s do it right after all:

LEFT JOIN with ON clause1 breedEnNames = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QBreed.breed.id, QBreed.breed.code, qbn.name)

3 .from(QBreed.breed)

4 .leftJoin(QBreed.breed.names, qbn).on(qbn.language.eq("en"))

5 .fetch();

And, voila, the result is [1, WLF, wolf], [2, COL, null] – with collie as well, although

without the name localized to English. Now we could add another condition to filter these cases

and report them – .where(qbr.name.isNull()) would do the trick, this time as a WHERE clause.

But this is the essence of ON. It’s a special WHERE that works very closely with related

JOIN and while the difference is virtually none for inner joins, it is essential for those outer

ones.

Dropping to-one annotations

Having accepted that we’re out of pure JPA land it is otherwise easy to get rid of to-one relationships. Instead of:

1 @ManyToOne

2 private Breed breed;

We can simply map the raw value of the foreign key:

1 @Column(...)

2 private Integer breedId;

If you want to load Breed by its ID, you use EntityManager.find explicitly. This has domain

consequences, because unless we give the entities some way to get to entity manager, such a code

cannot be directly on the entity. We will try to mend it and bridge this gap that JPA automagic

creates for our convenience – which is a good thing, and better part of the abstraction. The point

is there is no technological problem to obtain the referenced entity by its ID.

Queries are where the problem lies. Firstly, and this cannot be overcome with current JPA, we need

to use root entity in the JOIN clause – both EclipseLink and Hibernate now allow this.

This enriched experience cuts both ways, of course, as we may believe we’re still in JPA world

when we’re in fact not (my story). Second thing we need is ON clause, which is something JPA 2.1

provides. As discussed at the end of previous sections, ON clauses were generated for joins

before – but only as implied by the mapping and a particular association path used in the join.

We need to make this implicit ON condition explicit. Let’s see an example:

1 List<Dog> dogs = new JPAQuery<>(em)

2 .select(QDog.dog)

3 .from(QDog.dog)

4 .leftJoin(QBreed.breed).on(QBreed.breed.id.eq(QDog.dog.breedId))

5 .where(QBreed.breed.name.contains("ll"))

6 .fetch();

The key part is how the leftJoin is made. Querydsl doesn’t mind at all that we’re breaking JPA

rules here, it allows root entity and produces JPQL that works the same like the following code:

1 List<Dog> dogs = em.createQuery(

2 "select dog from Dog dog left join Breed breed on breed.id = dog.breedId" +

3 " where breed.name like '%ll%'", Dog.class).getResultList();

So this leaves us covered. Queries are just a bit more explicit, but otherwise nothing you would

not write into your SQL. We can argue that this way we can compare that breedId with any other

integer and we’re loosing the safety that ORM mapping gives us. On the mapping you specify what

columns are related on a single place and not in each query. This is true, indeed, although not

really a big deal. When talking to your DB admins they will probably see even better what you do,

although smart DBAs have no problem to understand JPQL either. But with dropping the mapping we’re

loosing this comfort too. In theory we could leave some logical mapping information on the

attribute, but without redesigning JPA we cannot benefit it in our queries anyway. We will try to

tackle the problem of missing metadata on the plain FK-typed attribute later in this chapter.

Ad hoc joins across tables

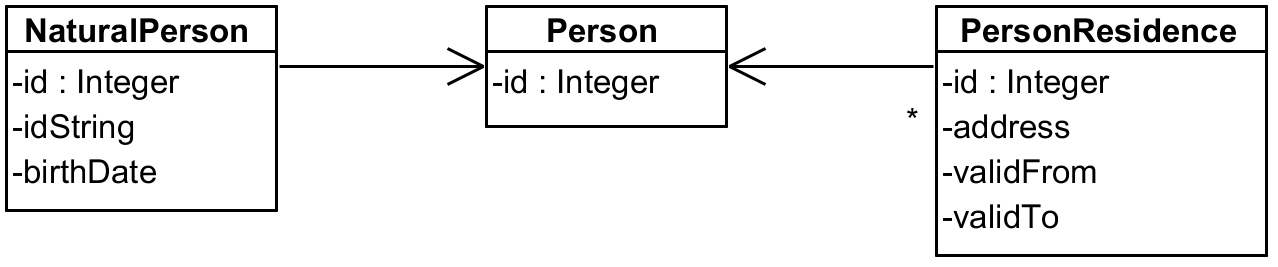

It’s not that rare to see tables with a shared ID value. In the following picture Person has

an ID column (its primary key) and other two tables share the same value as both their PK and FK

into the Person table:

Now imagine a situation we want some information from NaturalPerson table and its residence

but we don’t need anything from Person table itself. With JPA/ORM you need to join all three

tables or you need to map direct relationships across the tables as well – that requires dual

mapping to two different object types which is really superfluous. With ad hoc joins you have

no problem at all, we can simply join tables on the side using ON condition for equality of

their id attributes.

Even beyond this shared ID example there are many cases when ad hoc join is practical. Sometimes you need to build a report with join on a column that is not PK/FK pair – although there may be better ways than ORM to produce a report.

Loading the relationship from the entity

Queries are typically executed in the context out of the object itself – in a repository or DAO,

you name it. There is no problem to get hold of EntityManager at these places. But if you want

some loading from your entity, things necessarily get a little messy. But before we get to the

messy part let’s step back a little, because we have two broad options how to do it:

- We can have a real object attribute, but

@Transient, and we can load it when the scenario requires it. This is actually pretty handy because you can load the entity with its relations with an optimized query – especially if you don’t expect that data in the cache, or don’t want to use the cache at all, etc. Very explicit, but does exactly what it says. This does not require us to put any infrastructure code into the entity as we fill the attribute from the outside in a code that loads the whole object graph. - We can load it lazily when and if needed. But we have to make explicit what JPA does under the surface and what we don’t see on the entity – or we can develop our solution, but I’m not sure it’s worth it for this problem.

The first solution is obvious, so let’s see what we can do about the other one. Let’s start with

adding the method returning our entity – in our case we have a Dog with breedId foreign key

mapped as a raw value of type Integer. To load the actual entity we may try something like:

1 public Breed getBreed() {

2 return DaoUtils.load(Breed.class, breedId);

3 }

Ok, we cheated a bit, I admit – we moved the problem to that DaoUtils, but for a good reason.

We will need this mechanism on multiple places so we want it centralized. That load method then

looks like this:

1 public static <T> T load(Class<T> entityClass, Serializable entityId) {

2 EntityManager em = ...; // get it somehow (depends on the project)

3 return em.find(entityClass, entityId);

4 }

Ouch – two examples, cheating on both occasions. But here I cannot tell you how to obtain that entity manager. The method can reach to a Spring singleton component that makes itself accessible by static field, for instance. It isn’t nice, but it works. The point is that entity is not a managed component so we cannot use injection as usually. Static access seems ugly, but it also frees the entity from a reference to some infrastructural component and leaves it only with dependency to some utility class.

It is important to be familiar with the implementation of an injected EntityManager – in case of

Spring their shared entity manager helps us to get to the right entity manager even if we get to

the component via static path. I would probably have to consult Java EE component model to be sure

it is possible and if it is reliable across application servers.

Other option how to smuggle in the entity manager utilizes a ThreadLocal variable, but this means

someone has to populate it which means life-cycle – and that means additional troubles.

In any case, it is possible to add getter for a relationship on the entity, but it calls for some rough solutions – so if you can keep such an access somewhere else (data access object, for instance) do it that way. Otherwise we’re getting dangerously close to Active record pattern which by itself is legitimate, but doesn’t fit JPA. True – JPA provider can cheat somehow undercover, but we rather should not.

If you decide to load the relationship in some arbitrary code and you have only access to the entity, perhaps you can introduce DAO to that code. If you feel you’re making this decision too high in the layer model (like on the presentation layer maybe?), perhaps it should be pushed lower where the DAO is available. I’m not totally against static backdoor from the non-managed code to the managed component, but at least we should be aware of the cost and compare it with the cost of not doing it.

Loosing information without mapping annotations

When we map foreign key instead of the relationship we often loose important piece of information

– that is what type it leads to. Sometimes it is clear, e.g. with Integer breedId you can easily

guess it leads to Breed. But there is no type declaration anywhere around to click on when using

IDE. Even worse, the foreign key often describes the role instead of the type – which I personally

prefer especially when there are multiple relationships of the same type. So instead of terrible

client1Id and client2Id you have ownerId and counterpartyId. The names are descriptive, but

the type information is gone altogether.

For this – and also for means to automatically check validity of these IDs for newly stored or

updated entities – we developed custom @References annotation. With it the mapping for a foreign

key may look like this:

@References annotation1 @References(type = Breed.class, required = true)

2 private Integer breedId;

I believe the documentation factor is the most important one here, but we can also check the references on an entity like this:

ReferenceChecker1 new ReferenceChecker(em).checkReferences(lassie);

This either does nothing when everything is OK, or it fails with some exception of your choice depending on how you implement it. Our version is similar to this example on GitHub. If you go through the code you notice that it can do more than just checking – it can also push the real entities to some transient fields, for instance. Such a mechanism can be easily incorporated into validation framework you use if you wish to.

Wrapping it up

I presented a solution to our to-one problems – to use raw foreign key values. This bends the

JPA rules a bit and builds on the availability of the ON clause introduced in JPA 2.1. However,

JPA specification currently does not allow us to use root entity paths with JOINs – which is

required for queries. Only association paths are allowed now. This feature may come in later

versions and it is already supported by all the major players in the field – Hibernate,

EclipseLink and DataNucleus.

Mapping raw foreign key value may lead to some logical information loss, which can be easily mended by custom annotation. I’d like to see standard JPA annotation for this, otherwise schema generation would not be fully functional.

Another solution is to use a single mapping like today and having hint for JPA to fetch only the ID

portion of the related object. This may not work well with cascade=PERSIST when persisting new

entities pointing to existing ones, although the specification allows it to work (but also allows

to throw exception thanks to magical usage of “may” in the specification text). This solution

preserves current query mechanics, and actually is least intrusive of them all.

Finally, the JPA specification could mandate LAZY – this is something where Hibernate seems

quite reliable out of the box without any configuration hassle. On the other hand, I saw many

questions asking how to make this relationship lazy in Hibernate, so it probably is not universally

true. Promoting LAZY from a hint to a guaranteed thing would require JPA providers to use some

bytecode magic (which is not clean from Java language perspective), but it would also end a lot of

debates how to do it right.