Table of Contents

How to Create Masters and Mastery in a Classroom Setting

If you can follow the next sixty seconds, you will see something about modern AI that most computer scientists never learn. Recognize the patterns of cognition that apply to BOTH human and AI. Master them in one, and you gain immediate insight into the other.

I want you to stand with me at a particular spot on the Kentucky-Virginia border, because the entire AI attention mechanism can be seen from that overlook if you know where to look. Let me show you what I mean.

Road Versus Map

At the center of Figure 1, “Overlooking road to Breaks Interstate Park, April 27, 2013,” from left to right, you see a railroad track to the left of the river, a river, and to the right of the river a highway ascending to where I took the photograph. Just to the right of center you can see the view of the road widens, with the road not hidden by trees. That is the monument to an unknown soldier which you will see in the next photo.

Everything in front of you (the railroad, the river, the highway) is about to become a correct structural model of how LLMs process information. How you teach this insight is a radically different way of teaching computer science, one that transforms students into masters.

Training Data Cutoff Date

I became familiar with the area shown in this photo by driving that road several times over the years, in both directions. I have a fairly clear memory (i.e., fairly clear mental model) of Breaks Interstate Park, but that mental model has a limitation.

Do you see the limitation? I have a mental model of Breaks Interstate Park as it existed twelve years ago (2013). It has been more than twelve years since I last drove along that river. My training data cutoff date, the point past which I have no knowledge, is April 27, 2013, based on the timestamp of my most recent photograph of Breaks Interstate Park.

With Large Language Models, a key constraint you need to remain aware of is the training data cutoff date. I could look online to see if anything has changed concerning Breaks Interstate Park. But I have no way of knowing based on my digital photo collection. Some LLMs are capable of doing on-the-spot information searches, but others are limited to whatever training data has been ingested, plus any information you supply as part of your LLM conversation. Each of these possibilities is extremely useful, but you need to know which type of system you are working with.

The parallel is exact:

- My photographs: April 27, 2013

- Claude 4.5’s training cutoff date: July 2025

- In both cases: fixed knowledge base followed by inferences made from that base

Waypoint Details

Figure 2, “Burial place of unknown soldier murdered while returning home,” shows the waypoint visible in the previous photograph. The main highway passes to the left, with the paved turnout to the right. The marker explains this was a soldier killed by an unknown assassin while likely returning to his home. Local residents handled his burial. The century-old rosebush in the photo, protected by posts, long since faded from conscious memory until I looked at the image again.

To continue this analogy of building up a knowledge base, I gained more information by stopping and reading the waypoint marker than if I had simply continued driving on by. The photograph captures details that, a decade later, I would not have remembered. With this photograph to remind me, I do remember stopping there.

Multiple Information Layers

Thanks to EXIF data embedded by my camera into the photos, I can map direction of travel via several other photos in my digital library. The EXIF data (timestamp and exact GPS location) add another information layer. Combined across photos, these layers let me reconstruct a map. LLMs also stack multiple information layers, but in a different form.

I took the photos simply as tourist memories. But that embedded metadata, when combined across multiple photos, creates geographic information. If I were a mapmaker, I could draw a map with terrain sketches by combining those two layers. I use the word “layers” here, referring to the visual images as one layer and the GPS data as another layer, because that is the term used by Large Language Models. LLMs have a similar concept of information layers, which we will explore below.

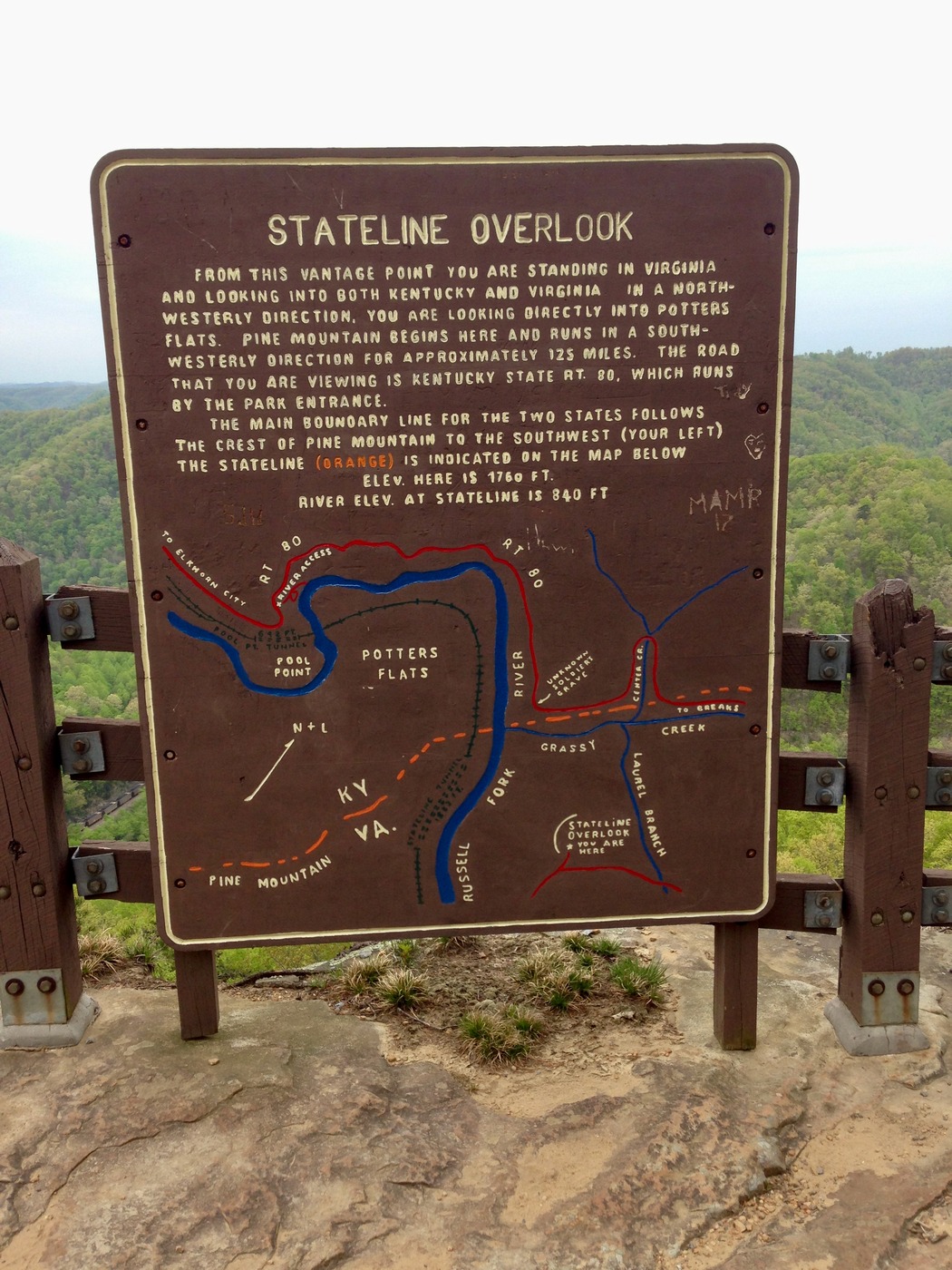

Now look at the information from a completely different perspective. Figure 3, “Stateline overlook map and description,” shows a map of the overlook itself, standing at the same spot where I took the terrain photo, but now looking at how a mapmaker organized that same information. The overlook itself (“you are here”) is at the bottom of the map, slightly right of center. The map shows the railroad, river, and highway, with the unknown soldier’s grave location marked just right of center on the map.

Parallel and Equivalent Routes

The point of this travel analogy is simple: we experienced two routes to the same information. (From a teaching perspective, the point is that we experienced two routes.)

Definition. The “mesh” is the result of the Large Language Model ingesting training data, a process reputed to cost hundreds of millions of dollars for the largest models such as ChatGPT and Claude. The resulting millions of weighted connections enable massively parallel statistical pattern recognition. Generally speaking, the mesh is created once, and remains unchanged throughout that model’s production deployment.

- Route 1: sequential (the road): I gained information by actually travelling through the terrain, noticing details one at a time: each curve, the rosebush at the gravesite shaped or pruned (I cannot tell which from the photo) into a rectangle like a headstone. I enjoy trees, and noticed many individual trees. I know to watch for changes in tree species as I change elevation. Here I am making connections one at a time, driving the highway up to the overlook while appreciating the ground-level view along the way.

- Route 2: holistic (the map): A mapmaker compiles the same information but organizes it spatially, showing all relationships at once. From the overlook, I see the forest, railroad, river, highway all visible simultaneously in their relationships to each other. As we will see, the phrase “simultaneously in their relationships to each other” is a key concept within Large Language Models. This concept is what LLMs call “the mesh.”

Shifted Perspective

Before August 5, 2025, I thought of the mesh as that static engraved map. I understood LLMs had “millions of weighted connections” but saw them as frozen, unchanging. The sunset photo (explained below) showed me what I had missed: the terrain is fixed, but what flows through it changes constantly. Trains approach, traffic moves, water rushes, attention shifts. That is the attention mechanism: dynamic flows through fixed structure.

On August 5, I suddenly realized that this is the fundamental distinction between how I create mental models (one connection at a time) and how LLMs process information (as a mesh, considering everything at once). Suddenly I saw it.

That blinding flash of understanding knocked my socks off: with a sudden shift in perspective, how I think matched how AI “thinks.”

Grasping that how you think matches how AI “thinks” is the key to pervasive AI literacy at all levels. I have enumerated patterns of cognition that apply to both human and AI in The Wizard’s Lens (linked at the end).

The Breaks Interstate Park website includes a photo (as of October 2025) from the same Stateline Overlook. It is the same location, different angle, looking past the engraved sign to a gorgeous sunset in the distance. (The website prohibits reproducing the photo here, which actually helps my description, because you need to visualize it.)

Recall that before August 5, the engraved map on the wooden sign is how I visualized an LLM: fixed and unchanging. I knew my understanding was inadequate, so I began a conversation with Claude aiming for better understanding of the LLM Attention Mechanism. I was not looking to solve any particular problem other than trying to improve my own understanding. This was a sustained and guided conversation with a specific objective.

To continue with the Stateline Overlook analogy, the engraved map is fixed. It shows all the relationships at once: railroad left, river center, highway right, terrain unchanging. When I said “LLMs process information as a mesh, considering everything at once,” I was picturing that static map.

But the sunset photo shows something different. It is the same overlook, but continuously changing. Sunlight shifts. Traffic flows. The multiple locomotives bringing the train up and through the Breaks are distinct from the high-pitched squeals of the train wheels going around the bend in the river; ears tell me a train is coming long before it is visible from the overlook. Water rushes through the rapids and around the river bend. The terrain is fixed, but what flows through it changes constantly.

This was my revelation: the mesh is fixed, but attention flows through it dynamically.

The trained model with its millions of weighted connections is like the terrain. It is fixed. The mesh is fixed, but attention flows through that mesh dynamically, producing different pathways depending on context.

This “attention flow” is like my ears drawing my attention to the heavy low-pitched locomotive noise approaching when the train wheels are already squealing around that bend. My past experience tells me that, in addition to the leading locomotives I already saw pulling the train around the bend, there is another locomotive in the middle of the train, or more likely at the end of the train, that helped push the train across the Breaks pass and remains part of the train as it continues downriver below Stateline Overlook.

In the same way, movement on the highway might pull my eyes (and attention) to the right. I can see the rushing water and might note kayakers who ran the rapids even though I am too far away to hear the river. Thus my attention shifts continuously through a fixed landscape, with different stimuli triggering different points of focus.

LLM attention mechanisms work the same way. Each “current” of attention examines the same input from a different angle. These attention currents operate in parallel, the way sight, sound, and motion cues all interpret the same overlook differently and simultaneously. LLMs call these “attention heads.”

I form conclusions based on what my eyes and ears tell me. In analogous fashion, LLM attention heads pass what they noticed (relationships and associations) through the LLM’s “feed-forward network” which integrates and transforms these signals, much the same way my mind integrates what my eyes and ears perceive at the overlook.

Each attention head, within the Large Language Model attention mechanism, notices different relationships. Then they combine their results, just as my own perception combines what I see, hear, and feel at the overlook. That perception might well be colored by my attitude at the time. (Having passed into the mountains with lots of trees, my attitude at the time was almost certainly good.)

Same Pattern Different Context

Why do people find attention mechanisms intimidating? Because they see the mathematics and assume they need to understand implementation details. But you do not need to understand fluid dynamics to appreciate a river’s flow. (On the other hand, running those rapids will produce a far deeper understanding of fluid dynamics. The Russell Fork Whitewater zone is rated Class III-IV depending on flow. Parts are rated IV-V and have produced fatalities.) In the same way, I do not need to understand neuroscience to notice that a train’s horn shifts my attention.

The same is true for working with LLMs. Understanding that attention flows dynamically through a fixed structure is the essential insight. The mathematics are the implementation, not the concept. Enjoying the Stateline Overlook as it continuously changes while you watch and listen: that is the same concept, the same essential insight.

Classroom Practice

When I answer questions in the classroom, I do not answer from knowledge. My answers expose my mental model of that knowledge. In so doing, I am addressing a known gap in computer science education: the transmission of mastery in a classroom setting.

I am most comfortable working with true experts in the field, such as professors of computer science. Experts’ hard-won expertise means that we can have a real conversation. This comfort is not due to arrogance; it is due to a shared cognitive framework. We both see past the surface and recognize the system in play.

Cray Research, in the 1980s, had prestige. Customers such as Lawrence Livermore Laboratory or Exxon sent their very best people to Cray Research for software training. I loved teaching operating system internals, assembly language on bare metal, because we had backgrounds in common. That particular background has been lost to time, but I now realize those very cognitive skills fill the modern gap in AI literacy.

Mental Models

In the classroom 38 years ago, I created mental models of each of my students, their degree of engagement, and their background relative to the subject at hand. This helped me address “the question behind the question.”

My cognitive framework allowed me to form hypotheses. This guided me in asking questions of my students, which confirmed or adjusted my hypothesis. I was continuously and consciously refining my visualization of the class participants throughout the course. I was visualizing the interactions of a dynamic system.

I already had a clear fixed model of my course material. The difference between the two (student context versus learning objectives) guided me in ensuring student needs were met. I knew exactly what questions to ask of this group of students to confirm my own view of the situation as instructor.

Working from a mental assessment of your students’ progress is a powerful technique, but it stems from something far more powerful: visibly modeling your thought process for your students. Teaching your students how you think is the mechanism for mastery transmission in the classroom.

This process is counterintuitive. Otherwise you would already be doing it. That fact means you need to cultivate a new set of habits. Such habits come from deliberate practice coupled with close observation of your own ways of thinking (metacognition).

Thinking About Thinking

I must emphasize: thoughtful, continuous metacognition is the counterintuitive foundation of this technique. I continuously make mental models of my process of making mental models. This is the Shewhart Cycle applied to metacognition: Plan, Do, Check, Act. Do you see the connection? In modeling your own thought process to yourself, you can easily articulate that process to your students because you already articulated it to yourself.

You have also conveyed the fundamental concept of recursion through demonstration using neither functional nor declarative techniques. “Thinking about thinking” and “modeling the process of modeling” are higher-level techniques, examples of a transcendent pattern wherein mathematical or algorithmic recursion is a specific implementation.

To illustrate the significance of this type of technique, consider how Academician Viktor Glushkov, the founder of Russian cybernetics, introduces recursion. For me, the following explanation is “heavy going” due to unfamiliar concepts:1

From these elementary arithmetic functions we can construct increasingly complicated functions by using some general methods of construction. In the theory of recursive (constructive arithmetic) functions three operations are of great importance: the operations of superposition, primitive recursion, and the least root…

The operation of primitive recursion makes it possible to construct n-place arithmetic functions (a function of n arguments) from two specified functions, one of which is an (n-1)-place and the other an (*n+1)-place function…

For correct understanding of the operation of primitive recursion it should be noted that every function of a lesser number of variables can be regarded as a function of any greater number of variables. In particular, constant functions, which can naturally be regarded as functions of zero arguments, if necessary can be considered as functions of any finite number of arguments.

For me, constructive arithmetic is a difficult concept to grasp on its own. But introducing the mental model of “thinking about thinking” gives me a solid frame of reference. I can then pick apart Glushkov’s explanation by analogy.

Classroom Question Answering

When I answer a question in the classroom, I can usually give a direct answer. But then I consider: what might be the question behind the question? My mental models of the material and of my student guide my discernment. I can ask questions in searching for the right question to answer.

Far more importantly, I can explain my thought process. I can often ask a series of questions guiding my students through my thought process in terms of mental models of a system in play (i.e., a dynamic system with forces acting on it). Or I can directly describe my mental model: “I see the situation as such-and-such. Let’s look over here to see that sequence of events and see if it fits.”

Transmitting knowledge, as the subject matter expert, does not fill the gap. Transmitting while demonstrating my way of thinking (as the subject matter expert) does. This approach derives from an important constraint:

If I cannot demonstrate something, I do not feel qualified to teach it. But if I can demonstrate it, I feel obligated to teach it.

You will recognize that constraint as the master’s obligation to propagate the craft. Computer science education, obviously, is a means to do just that. Teaching via demonstration in a way that the student experiences the demonstration is a solid technique. The closest model I have found for the classroom is exposing and modeling the expert’s thought process. This technique works as well outside the classroom as within, and thus becomes a career skill.

The reciprocal process also enables learning, both within and beyond the classroom. When the student forms the habit of articulating his or her thought process, the mentor can work with that and address misconceptions in terms that will make sense to the student.

Lived Experience

This is what I mean by “answering from lived experience”: “expert-level way of thinking.” This is a counterintuitive orientation because that is not the usual definition of “lived experience.” This dissonance is the transformational insight. Mastery is not expert-level knowledge. Mastery embodies expert-level processes and ways of thinking.

Mastery does not come from leveling-up “+1” from intermediate or journeyman. Mastery represents operating on a different plane entirely. That is why the knowledge itself, in a classroom setting, is far less important than modeling how I acquired that knowledge.

Computer science education rarely teaches this, because most instructors never make their thinking visible, even to themselves. This is a lost Cold War-era skill that has regained crucial importance today: this is the technique that enables intuitive AI literacy.

Consider the potential of all computer science students leaving the classroom with the ability of mastery transmission. Contained within that skill is the ability to gain mastery in the first place.

There is work involved: a new set of habits to form.

Three-Step Process

This is the method I use habitually and continuously. It is my way of making a system visible to myself by identifying its boundaries and constraints. The outcome is a remarkably clear mental model. Systems have constraints, and such mental models become predictive guides providing insights and suggesting strategies.

- First, create a mental model of the system as a whole, including describing its boundaries. The “system” could be your classroom with your current set of students.

- Second, identify the interacting forces of the system.

- Third, pinpoint the critical limiting factor in the sense of Liebig’s Law of the Minimum (plant growth is bounded by the relatively scarcest nutrient). This is your point of maximum leverage.

The above habit, over time, becomes intuitive and automatic, often formed in the blink of an eye. But at first you need to consciously practice with close observation (metacognition). Your students also need to consciously practice to internalize this technique.

Mental Models Enable Analogies

By forming mental models of my material, I find it easy to teach by analogy. I see how the system operates as a whole. I can then see how to present a similar system in familiar terms. I can see the difference between a current (uninformed) view and my view of the system at hand. I can show the required shift in perspective, and then show the system itself (via well-understood analogy).

I call this view based on mental models “The Wizard’s Lens” because that way, I get to be the wizard.

Educational Gaps

This one technique can transform the outcome of computer science education throughout the United States. I know its power from long experience.

But this does not address the urgent need for AI literacy across the board, from K-12 through postdoctoral research. For that I wrote an essay and two books. The first of the two books enumerates those patterns of cognition that describe both human and AI.

V. M. (Viktor Mikhaĭlovich) Glushkov, Introduction to Cybernetics (Academic Press, 1966), 26-27.↩︎